Abstract

Objective

The association of type 1 diabetes mellitus with autoimmune thyroiditis or with celiac disease is frequently mentioned in literature, but the concomitant presence of these three autoimmune diseases, especially in adults, represents a rarity.

Case report

We present the case of a young man with severe generalized oedema admitted to the emergency department and diagnosed with severe hypothyroidism (TSH=100 μUI/mL, fT4 = 0.835 pmol/L) in the context of a long-lasting autoimmune thyroiditis (anti-TPO antibodies 64 UI/mL, anti-TG antibodies 17 UI/mL, the thyroid ultrasonography). At the same time, he was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes mellitus. He was also submitted to further tests which confirmed the diagnosis of celiac disease (endoscopy with intestinal mucosa biopsy, confirmed by immunological tests). The association of these three diseases slows down the process of reaching a final diagnosis and delays the adoption of a therapeutic strategy.

Conclusion

This case underlines the difficulty of differential diagnosis of severe oedema syndrome with polyserositis in a patient with polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. Whenever there is a suspicion of the association of these autoimmune diseases, the evolution of the patient is unpredictable and most medical results are highly dependent upon the decision of applying a concomitant treatment.

Keywords: polyglandular autoimmune syndrome, polyserositis, severe hypothyroidism

INTRODUCTION

Polyglandular autoimmune syndromes (PAS) represent the association of different autoimmune diseases, frequently endocrine disorders, where the diagnosis is established in the presence of at least 2 endocrine autoimmune diseases (1).While some of these disorders are quite frequent (e.g. hypoparathyroidism, thyroiditis, diabetes, candidiasis), others are rare (e.g. myasthenia gravis, Addison’s disease); while some disorders are symptomatic and allow for a rapid diagnosis, others are asymptomatic or often diagnosed after a long evolution with very few symptoms. Some authors consider that the diagnosis of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome represents an inappropriate medical term because the condition that it refers to often implies the association of non-endocrine autoimmune diseases (1). However, it is extremely important to recognize and diagnose these syndromes, the risk of association of several autoimmune diseases in the same patient and last, but not least, the fact that the relatives of these patients have an increased risk for any of the autoimmune disorders present and therefore require early diagnosis and treatment (2). Significant clinical observations about the association of several endocrine disorders or about the multiple glandular insufficiencies in the same patient go as far back as the early 1900s (1904 in Germany, by Paul Ehrlich, 1908 in France by Claude and Gourot) (3). In 1980, a group of authors led by Neufeld proposed a classification of PAS into 4 distinctive types: type 1 defines the association between Addison’s disease, hypoparathyroidism and cutaneo-mucosal chronic candidiasis; type 2 represents the association between adrenal insufficiency and autoimmune thyroiditis; type 3 is represented by autoimmune thyroiditis associated with any other autoimmune disease except for adrenal insufficiency; and type 4 is represented by the association between other endocrine disorders or autoimmune diseases (4). More recently, Kahaly (5) considered both epidemiological and genetic criteria and proposed a two-fold classification of these syndromes, namely type I (PAS I, very rare, juvenile forms) and type II (PAS II, more frequent forms, discovered in adults, with or without adrenal insufficiency). Irrespective of the classification employed, one may observe that thyroid autoimmunity is quasi-constant in patients with type 2, 3 or 4 PAS (the Neufeld system) or type II (the Kahaly system). Since thyroid autoimmunity often coexists with other significant autoimmune disorders and since hypo- or hyperthyroidism may have a negative impact upon the evolution of most associated disorders, it is imperative that patients should be properly evaluated and monitored. Autoimmune thyroiditis is generally considered the specific manifestation of organ autoimmunity and is usually associated with other autoimmune or endocrine disorders (6). While polyserositis is frequently encountered in hypothyroidism, anasarca is a rare medical condition.

We present a case of type 4 PAS (hypothyroidism, type 1 diabetes mellitus, celiac disease), where the presence of pleural, pericardial and peritoneal effusions and important peripheral oedema raised major problems of differential diagnosis, in the context of severe hyperglycaemia and serious malabsorption syndrome.

CASE REPORT

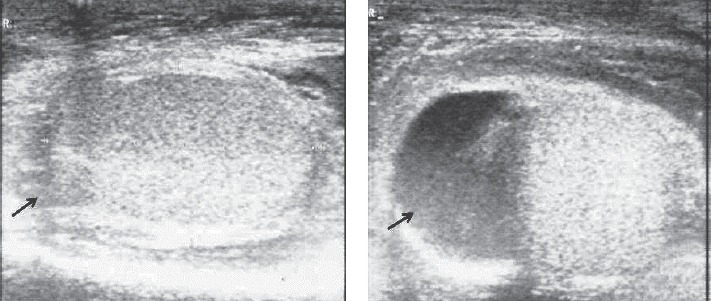

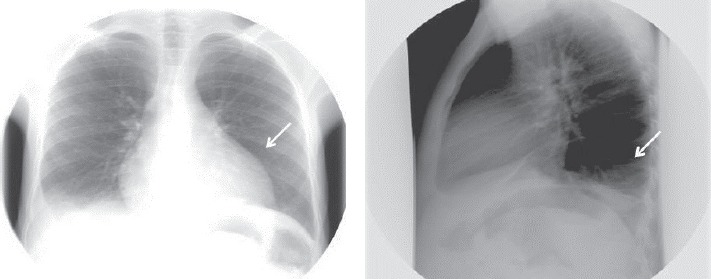

After an extensive period of bed rest, a 20- year old patient was brought to the emergency room with serious slowness and generalized oedema. The patient was informed about the required diagnostic and treatment procedures and signed the informed consent form. The initial tests excluded the following causes of the symptoms: renal (absent proteinuria, normal urea and creatinine), hepatic (normal liver enzymes and billirubin; liver steatosis in ultrasonography) and cardiac (no signs of cardiac failure). Given his generalized oedema and weakness, the patient was suspected of severe malnutrition or hypothyroidism; moreover, the high blood glucose value of 790 mg/ dl in a person with no previous diagnosis of diabetes eventually motivated the patient’s admission to the Clinical Centre for Diabetes, Nutrition and Metabolic Diseases. The patient’s admission note included the following basic information: conscious but depressed patient, underweight (weight = 44 kg, height = 162 cm, BMI = 16.7kg/m2), with slow deterioration of general state in the previous 4-5 years, aggravated in the previous 6 months (leading to bed rest), lack of appetite, slowness in movements and cold intolerance. Clinical observations: pale yellowish, dry and exfoliated skin, important oedema of hands and face (Fig. 1), lower limbs, scrotum (confirmed by ultrasonography, Fig. 2), bilateral rough vesicular breath sounds, diminished in the lower posterior chest walls; abnormally quiet heart sounds, BP=100/60 mmHg, distension of the abdomen, diffusely tender on palpation. The abdominal ultrasonography revealed the presence of small quantities of liquid in the inter-hepatic-renal region and in the iliac fossae; the ECG revealed the presence of low voltage waves which are characteristic of pericarditis. The chest X-rays confirmed the diagnosis of pleural effusion and pericarditis (Fig. 3). The initial treatment recommendations included i.v. fluid and insulin therapy for a progressive diminishing of blood glucose values (glycated Hb initial value was 13.8%). Blood test values confirmed the diagnosis of myxedema (TSH=100 μUI/mL, fT4 = 0.835 pmol/L) and the patient began immediate hormonal substitution therapy with levothyroxine 100 μg/day for 14 days and then 150 μg/day (the patient’s weight and celiac disease were taken into consideration). Also, a short-term corticotherapy (100 mg hydrocortisone hemisuccinate, 4 days) was recommended in order to avoid a functional adrenal crisis, because thyroid hormones are known to accelerate cortisol metabolism. The patient also presented normochrome normocitary anaemia, the initial values indicating Hb=9 g/dL and Ht=25.5%. Following the patient’s rehydration, the blood values indicated Hb=5.7 g/dL and Ht=15.6%, which required the administration of iso-group iso-Rh blood. Anemia tends to have a mixed etiology especially in patients with severe malnutrition and due to hemodilution of hypothyroidism.

Figure 1.

Facial oedema in the patient with anasarca.

Figure 2.

Ultrasonography of the right testicle (10 ml volume, normal structure) and right scrotum showing scrotal fluid.

Figure 3.

Chest X-rays showing pleural and pericardial effusions.

Complex diagnostic problems and therapy decisions required that the patient be admitted to hospital for a rather long period of time, namely for 6 weeks. Here is a summary of the medical problems that we had to address:

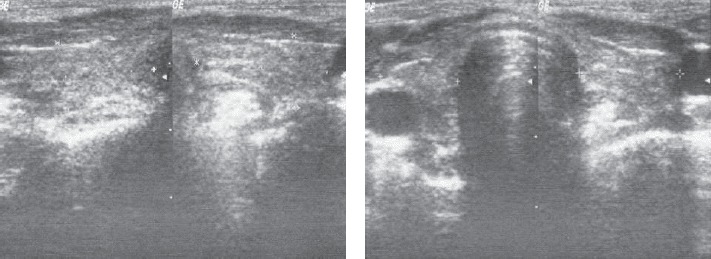

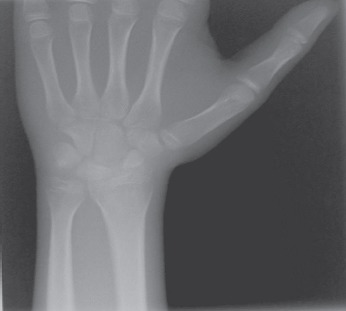

Understanding theaetiology of hypothyroidism, the exclusion of other endocrine disorders, and the selection of an adequate endocrine treatment. The patient was tested for anti-TPO antibodies (64 UI/mL, normal values < 20 UI/mL) and anti-TG antibodies (17 UI/mL, normal values < 20 UI/mL). These findings were corroborated with the ones elicited from the patient’s full thyroid examination (including the thyroid ultrasonography, Fig. 4) and they ultimately confirmed the diagnosis of autoimmune thyroiditis. Other forms of primary hypothyroidism were excluded due to clinical examination, medical history and thyroid ultrasound. The patient was also tested for the FSH, LH and testosterone levels, which, in accordance with the 3-4 Tanner pubertal stage, revealed values in normal ranges. The delay in pubertal evolution was considered in the context of long lasting untreated hypothyroidism. While both ACTH and cortisol values were within normal ranges, the PRL value was raised due to hypothyroidism. The CT scan of the brain (to exclude a possible pituitary gland hyperplasia secondary to severe long-lasting hypothyroidism) revealed no abnormalities. The X-ray of the wrist revealed the presence of fertile growing cartilage and a delayed bone age (bone age=12 years, Fig. 5), due to the long-lasting and severe form of hypothyroidism.

Figure 4.

Thyroid ultrasonography shows thyroid volume of 15 ml, hypoechogenic, non-homogeneous echostructure.

Figure 5.

X-ray of the wrist revealed the presence of fertile growing cartilage and a delayed bone age of 12 years.

The diagnostic confirmation for type 1 diabetes mellitus and the selection of an adequate treatment. Given his attested autoimmune thyroid disorder, the patient was tested to determine the level of anti- GAD antibodies (24.3 UI/mL, normal values 0-5 UI/ mL) and the level of C peptide (0.28 ng/mL, normal values 0.9-7.1 ng/mL). The detected levels confirmed the diagnosis. The patient went into partial remission during admission, which required negative titration of insulin doses, from a basal-bolus regime, to a regime with one injection of a long-acting insulin analogue.

It was also necessary to laboriously educate the young man and his mother regarding insulin administration, the importance and technique for self-monitoring of blood glucose, the preventive and curative treatment of hypoglycaemia and the adequate diet.

However, we need to address the suspicion of a celiac disease. During his admission time, the patient did not respond well to treatment; in fact his overall treatment response was considerably delayed and did not match all our medical expectations (e.g. slow reduction of oedema and polyserositis, despite the correct administration of hormonal substitution treatment; persistent hypoalbuminemia which was considered the reason for the persistence of oedema; anemia, overall weakness, and weight loss within the context of malnutrition). As a consequence, the patient was referred to a parental regime to correct his protein-caloric deficit (repeated infusions with desodated human albumin, dextrose solutions, iv vitamins and minerals); he was then referred to the enteral administration of vitamin and mineral supplements, and the per os correction of his protein deficit. The confirmed presence of two autoimmune diseases raised our suspicions for celiac disease. As a consequence, endoscopy was performed and intestinal mucosa biopsy collected. The morphological aspects detected were typical of the Marsh II celiac disease; the specific antibodies present also confirmed the diagnosis (IgG antigliadin antibodies 29 mg/L, normal values <18 mg/L, IgA tissue antitransglutaminase antibodies 24 U/mL, normal values <10 U/mL, IgG tissue antitransglutaminase antibodies 37 U/mL, normal values <10 U/mL). Following these results, we initiated a specific nutritional therapy (i.e. a hyperproteic, normoglucidic and normolipidic diet; the avoidance of foods with a high glycemic index, the selection of foods with a high content of proteins and a high biological value; gluten-free products).

We present in Table 1 the evolution of the patient’s parameters, which were initially altered. Table 2 presents other parameters, which were not modified during admission, but were necessary for monitoring and diagnosis.

Table 1.

The evolution of the patient’s parameters after 6 weeks of hospitalization

| Parameters | Normal values | Hospital admission values | Hospital discharge values |

| Glycemia | 70-110 mg/dL | 790 mg/dL | 126 mg/dL |

| Hb | 13-17.5 g/dL | 5.7 g/dL | 11.8 g/dL |

| Ht | 40.1-51% | 16.4% | 33.8% |

| Total protein | 63-83 g/l | 59 g/l | 68 g/l |

| Serum albumin | 3.5-5.2 mg/dL | 2.8 mg/dL | 3.9 mg/dL |

| Serum iron | 50-158 μg/dL | 40 μg/dL | 68 μg/dL |

| Ferritin | 30-350 ng/dL | 29.8 ng/dL | 34 ng/dL |

| Total calcium | 8.4-10.2 mg/dL | 7.46 mg/dL | 9 mg/dL |

| Magnesium | 1.6-2.6 mg/dL | 2.59 mg/dL | 2.57 mg/dL |

| TSH | 0.4-6 μUI/mL | 100 μUI/mL | 65 μUI/mL |

| fT4 | 12-22 pmol/L | 0.835 pmol/L | 16.82 pmol/L |

| Pericardial effusion at level of | - | Apex 10 mm | Apex 6 mm |

| LV 14 mm | LV 8 mm | ||

| RV 15 mm | RV 8 mm | ||

| Pleural effusion | - | Right – 30 mm | - |

| Left – 17 mm | |||

| Peritoneal fluid | - | 10-15 mm (inter-hepato-renal and the iliac fossa) | - |

Table 2.

Other blood test values

| Parameters | Normal values | Levels on hospital admission |

| Urea | 15-45 mg/dL | 48 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.7-1.3 mg/dL | 0.51 mg/dL |

| ALAT | 5-38 U/L | 36 U/L |

| ASAT | 5-41 U/L | 28 U/L |

| Total bilirubin | 0.2-1.2 mg/dL | 0.43 mg/dL |

| Uric acid | 3.5-7.2 mg/dL | 2.50 mg/dL |

| Cholesterol | 120-200 mg/dL | 178 mg/dL |

| Triglyceride | 35-150 mg/dL | 107 mg/dL |

| Anti-Tiroglobuline antibodies | <20 UI/mL | 17 UI/mL |

| Anti-TPO antibodies | <20 UI/mL | 64 UI/mL |

| C peptide | 0.9-7.1 ng/mL | 0.28 ng/mL |

| Anti-GAD antibodies | 0-5 UI/mL | 24.3 UI/mL |

| FSH | 1.5-17.4 mUI/mL | 15.63 mUI/mL |

| LH | 4.0-8.6 mUI/mL | 3.53 mUI/mL |

| Testosterone | 2.49-8.36 ng/mL | 3.96 ng/mL |

| Cortisol | 5-25 μg/dL | 26.5 μg/dL |

| Prolactin | 86-324 μUI/mL | 767.1 μUI/mL |

| Anti-gliadin IgG antibodies | <18 mg/L | 29 mg/L |

| Anti-transglutaminase IgA antibodies | <10 U/mL | 24 U/mL |

| Anti-transglutaminase IgG antibodies | <10 U/mL | 37 U/mL |

All medical facts should be considered with direct reference to the patient’s social background. Thus, in accordance with his declaration, the patient came from a very large and poor family, with a low level of education and with no health insurance. This explains the long evolution of the patient’s PAS, especially hypothyroidism, without any medical interventions and no diagnosis.

During his hospitalization, the patient was referred to a constant thyroid substitution therapy, in progressively increasing doses (100 μg/day for the first two weeks and 150 μg/day after) under clinical, ECG and TSH monitoring, reaching the cruise dose of 150 μg levothyroxine/day. Eventually, the medical team acknowledged a positive evolution of most of his clinical, biological and imagistic parameters (i.e. slow improvement of the patient’s general state, slow oedema attenuation, progressive reduction of TSH with normal fT4 after 6 weeks of treatment, reduction of pericardial effusion and disappearance of the pleural and peritoneal effusions). There was also a slow positive nutritional evolution, with some improvement in the protein, vitamin and mineral parameters. The patient and the family requested hospital discharge approval after 6 weeks of hospitalization.

DISCUSSION

We presented the case of a young man who was very late diagnosed with autoimmune thyroiditis and who was long suffering from myxedema and anasarca. It turned out that the patient also suffered from two other associated autoimmune diseases: type 1 diabetes mellitus and celiac disease. The clinical characteristics of each of these diseases were masked by their association (the dehydration secondary to hyperglycemia was masked by the oedematous syndrome from hyperthyroidism, the reduced metabolic rate in hypothyroidism masked the hypercatabolic signs characteristic to the development of type 1 diabetes mellitus, and the coexistence of celiac disease and malabsorption masked the polyuria and polydipsia secondary to hyperglycemia). The poor prognosis of the patient derived not only from the association of these autoimmune diseases found in an advanced state of evolution, but also from some severe co-existent malnutrition. The patient’s social background also impeded any previous medical evaluations and early diagnosis.

Various cases of autoimmune thyroiditis with hypothyroidism are often reported in the medical literature, yet their associations with type 1 diabetes and celiac disease are rarely found and discussed. Benedini et al. (7) recently reported on a case of a 74 year old woman diagnosed with a type 3 PAS in association with type 1 diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroid disease diagnosed in hypothyroidism, and pernicious anemia. In this case, the woman was diagnosed with diabetic ketoacidosis upon her emergency admission to hospital; subsequently, the patient was discovered to suffer from other autoimmune conditions, which initially masked all her symptoms and delayed overall diagnosis, hence, the screening for this type of patients is justified (8).

Recent data suggests that the development of diabetes usually precedes the diagnosis of hypothyroidism (9). Many research studies offer strong medical evidence to support the association between type 1 diabetes mellitus and thyroid autoimmunity (10- 13), and hence recommend the introduction of routine screening tests for this category of patients. There is another study involving type 1 diabetes patients that reveals another interesting aspect, namely that the prevalence of antithyroid antibodies and parietal gastric cell antibodies increases with age and diabetes duration. At the same time, the presence of anti-GAD antibodies is regarded in this study as a marker for the development of other autoimmune diseases in teenagers (14).

The special nature of our investigated case also resides in the fact that, on hospital admission, our 20-year old patient presented symptoms of anasarca, unlike the presence of only polyserositis, which is often seen in severe hypothyroidism (15,16). A similar case (17) was that of a 50-year old female patient who requested medical assistance for weight gain, important oedema and large quantity ascites, and in whom the ultrasonography showed pericardites. In fact, all these modifications resulted from severe hypothyroidism.

In young patients the association between pleural and pericardial effusion was present in the context of Graves-Basedow disease (also an autoimmune thyroid condition) and type 1 diabetes mellitus (18).

Another specific feature of this case was the absence of the adrenal deficiency which is usually associated with autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus and celiac disease in type 2 PAS. In our case the adrenal axis was unimpaired as evidence by the clinical examination and hormonal tests.

Celiac disease is another autoimmune condition of multifactorial aetiology and which is highly dependent upon the genetic background. Furthermore, it is often associated with other autoimmune diseases. The clinical manifestations are varied enough, including the classical malabsorption syndrome, but there are also asymptomatic cases (19). The association between thyroiditis and the celiac disease raises serious problems about the therapy with levothyroxine because the levels of TSH normalize after a gluten-free diet, requiring lower doses of levothyroxine, due to the important alteration of the intestinal barrier in celiac disease. The association between celiac disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus or autoimmune thyroiditis is frequently mentioned in the literature (20, 21), and there is enough evidence for the existence of some genetic susceptibility especially related to the HLA histocompatibility genes (22). However, to our knowledge, there are not many reported cases of PAS in adults that include celiac disease. This rare association has been reported in children (23, 24), yet predominantly in the context of genetic diseases (e.g. Down’s syndrome). One study involving children with type 1 diabetes mellitus revealed the association with celiac disease at a rate of 7.8% and with anti- thyroid antibodies at a higher rate, 29% for anti-TPO antibodies and 23% for anti-Tg antibodies (25). The authors opined that patients with type 1 diabetes should be screened annually for antibodies specific to celiac disease and autoimmune thyroiditis, regardless of the presence of any specific symptoms.

A relatively similar study involving a much larger group of type 1 diabetes patients suggests the need for patients’ annual screening for thyroid autoimmunity (especially in women) and celiac disease (especially in younger patients) (26). Furthermore, these researchers have also reported the presence of certain HLA haplotypes, which would confer increased susceptibility to each autoimmune disease. All these facts and data support the idea that celiac disease is the second most frequent autoimmune disease in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, after autoimmune thyroiditis (27) and it is asymptomatic in over 50 % of the cases (28).

In conclusion, the association of type 1 diabetes mellitus with autoimmune thyroid disorder and with celiac disease may result in type 4 PAS. The case reported in this paper was difficult to approach because it required the differential diagnosis of a severe oedematous syndrome with polyserositis in a seriously ill patient, with multiple organ problems. In our daily medical practice, this pathological association raises important diagnosis problems, mostly because the symptomatology of each of these diseases can be hidden by the others. As a consequence, therapy decisions are difficult to take and put into practice. Moreover, the malabsorption syndrome usually associated with celiac disease often hinders our most adequate treatment solutions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Professor Corin Badiu, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania, for the constant collaboration and support and particularly for the pertinent suggestions and proof reading of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest concerning this article.

References

- 1.Eisenbarth GS, Gottlieb PA. Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(20):2068–2079. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra030158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenbarth GS, Gottlieb PA. The immunoendocrinopathy syndromes. In: Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, editors. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Tenth edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003. pp. 1763–1776. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpenter Cc, Solomon N, Silverberg SG, Bledsoe T, Northcutt Rc, Klinenberg, Bennett Il, Jr., Harvey Am. Schmidt’s Syndrome (Thyroid And Adrenal Insufficiency). A review of the literature and a report of fifteen new cases including ten instances of coexistent diabetes mellitus. Medicine (Baltimore) 1964;43:153–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neufeld M, Maclaren N, Blizzard R. Autoimmune polyglandular syndromes. Pediatr Ann. 1980;9(4):154–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahaly GJ. Polyglandular autoimmune syndromes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161(1):11–20. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wémeau JL, Proust-Lemoine E, Ryndak A, Vanhove L. Thyroid autoimmunity and polyglandular endocrine syndromes. Hormones. 2013;12(1):39–45. doi: 10.1007/BF03401285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benedini S, Tufano A, Passeri E, Mendola M, Luzi L, Corbetta S. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome 3 onset with severe ketoacidosis in a 74-year-old woman. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/960615. 960615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riley WJ, Maclaren NK, Lezotte DC, Spillar RP, Rosenbloom AL. Thyroid autoimmunity in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: the case for routine screening. J Pediatr. 1981;99(3):350–354. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mouradian M, Abourizk N. Diabetes mellitus and thyroid disease. Diab Care. 1983;6(5):512–520. doi: 10.2337/diacare.6.5.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Severinski S, Banac S, Severinski NS, Ahel V, Cvijovic K. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of thyroid dysfunction in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Coll Antropol. 2009;33(1):273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin P, Huang G, Lin J, Yang L, Xiang B, Zhou W, Zhou Z. High titre of antiglutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibody is a strong predictor of the development of thyroid autoimmunity in patients with type 1 diabetes and latent autoimmune diabetes in adults. ClinEndocrinol (Oxf) 2011;74(5):587–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.03976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reghina AD, Albu A, Petre N, Mihu M, Florea S, Fica S. Thyroid autoimmunity in 72 children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: relationship with pancreatic autoimmunity and child growth. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25(7-8):723–726. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2012-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Khawari M, Shaltout A, Qabazard M, Al-Sane H, Elkum N. Prevalence of thyroid autoantibodies in children, adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24(3):280–284. doi: 10.1159/000381547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karavanaki K, Kakleas K, Paschali E, Kefalas N, Konstantopoulos I, Petrou V, Kanariou M, Karayianni C. Screening for associated autoimmunity in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Horm Res. 2009;71(4):201–206. doi: 10.1159/000201108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindsay RS, Toft AD. Hypothyroidism. Lancet. 1997;349(9049):413–417. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)80050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottehrer A, Roa J, Stanford GG, Chemow B, Sahn SA. Hypothyroidism and pleural effusions. Chest. 1990;98(5):1130–1132. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.5.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gotyo N, Hiyama M, Adachi J, Watanabe T, Hirata Y. Respiratory failure with myxedema ascites in a patient with idiopathic myxedema. Inter Med. 2010;49(18):1991–1996. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Algun E, Erkoc R, Kotan C, Guler N, Sahin I, Ayakta H, Uygan I, Dilek I, Aksoy H. Polyserositis as a rare component of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type II. Int J Clin Pract. 2001;55(4):280–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fasano A. Systemic autoimmune disorders in celiac disease. Curr Opin Gastroen. 2006;22(6):674–679. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000245543.72537.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belei O, Brad GF, Marginean O. An adolescent suspected by IPEX syndrome: immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy X-linked. Acta Endocrinol (Buc) 2015;XI(1):103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jinga M, Jurcut C, Vasilescu F, Balaban VD, Maki M, Popp A. Celiac gluten sensitivity in an adult woman with autoimmune thyroiditis. Acta Endocrinol (Buc) 2014;X(1):128–133. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denham JM, Hill ID. Celiac disease and autoimmunity: review and controversies. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13(4):347–353. doi: 10.1007/s11882-013-0352-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lammer C, Weimann E. Early onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and celiac disease in a 7-yr-old boy with Down’s syndrome. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9(4 Pt 2):423–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aycan Z, Berberoglu M, Adiyaman P, Ergur AT, Ensari A, Eyliyaoglu O, Siklar Z, Ocal G. Latent autoimmune diabetes mellitus in children (LADC) with autoimmune thyroiditis and celiac disease. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2004;17(11):1565–1569. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2004.17.11.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ergur AT, Ocal G, Berberoglu M, Adiyaman P, Siklar Z, Aycan Z, Evliyaoglu O, Kansu A, Girgin N, Ensari A. Celiac disease and autoimmune thyroid disease in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: clinical and HLA-genotyping results. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010;2(4):151–154. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.v2i4.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messaaoui A, Tenoutasse S, Van der Auwera B, Mélot C, Dorchy H. Autoimmune thyroid, celiac and Addison’s diseases related to HLA-DQ types in young patients with type 1 diabetes in Belgium. Open Journal of Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases. 2012;2(4):70–73. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volta U, Tovoli F, Caio G. Clinical and immunological features of celiac disease in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;5(4):479–487. doi: 10.1586/egh.11.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holmes G. Celiac disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus – the case for screening. Diabet Med. 2001;18(3):169–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]