Abstract

Objective: Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been isolated from various human tissues. Although they share cardinal stem cell features of self-renewal and multi-potency, they also seem to possess distinct characteristics depending on the tissue types they originated from. When developing stem cell-based therapies, MSCs with the most desirable characteristics should be chosen. However, our knowledge on tissue type-specific characteristics of MSCs is limited. Here, we comparatively studied the gene expression profiles of MSCs from different tissue types, and predicted target diseases suitable for each type of MSCs.

Methods: We harvested MSCs from human dental pulp and adipose tissue specimens and subjected them to gene expression microarray analysis. Characteristic gene expression signatures of the MSCs from each tissue type were identified using gene-annotation enrichment analysis.

Results: Dental pulp-derived MSCs exhibited gene expression signatures of neuronal growth, while adipose tissue-derived MSCs exhibited signatures of angiogenesis and hair growth. MSCs from each tissue type expressed a discrete set of genes encoding secretory peptides, which may function as paracrine factors.

Conclusions: MSCs derived from different tissue types demonstrated distinct gene expression signatures, which are suggestive of target diseases in clinical applications of the MSCs and stem cell-conditioned media. By expanding the analysis to MSCs from a wide range of tissue types, and by employing multiple omics approaches, a catalogue of MSCs and therapeutic targets can be generated.

Keywords: Transcriptome, Dental pulp, Adipose tissue

Introduction

Human mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) play pivotal roles in repairing damaged tissues; they migrate to sites of tissue damage, secrete soluble factors in a paracrine fashion to enhance wound healing, and sometimes differentiate into certain cell types to reconstruct tissues. They also exert immunoregulatory effects to suppress aberrant immune responses. Because of these properties, MSCs have attracted much interest in translational research as a therapeutic tool. MSCs, as well as stem cell-conditioned media and exosomes contained therein, have been used to treat diverse disorders[1], including cerebral infarction[2], spinal cord injury[3–5], diabetes mellitus[6], obesity[7], atopic dermatitis[8], inflammatory bowel disease[9] and liver disorders[10] .

Since the isolation of MSCs from bone marrow, MSCs have been harvested from various types of human tissues, including adipose tissue, dental pulp, and umbilical cord. By comparing MSCs from different tissue types, it is becoming apparent that MSCs are quite divergent. For instance, RNA sequencing revealed distinctively different gene expression profiles in MSCs from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and palatine tonsils[11]. Additionally, a recent proteomic study demonstrated discrete secretomes by comparing bone marrow-derived MSCs and dental tissue-derived MSCs[12]. For successful clinical application of MSCs, cells with the most desirable characteristics for treating a target disease should be chosen.

Methods

Cell sources

Exfoliated deciduous teeth (n=6), permanent tooth (n=1), and adipose tissue from abdomen (n=2), buccal pad (n=2) and orbit (n=2) were obtained from healthy donors with written informed consent. Tissues were enzymatically processed and cells were cultured using MesenCult-XF (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Fetal fibroblasts WI-38 were obtained from Cell Bank (JCRB Cell Bank, Osaka, Japan).

Gene expression microarray

Cultured cells were stored in RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tokyo, Japan) and total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). RNA samples were processed and applied to SurePrint G3 Human GE 8x60K v3 Microarray (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) at Biomedical Center (Takara Bio, Yokka-ichi, Japan).

Gene expression data analysis

Expression levels of individual genes were compared between samples by multiple testing using Significance analysis of microarrays (SAM; http://statweb.stanford.edu/~tibs/SAM/), in which genes that showed expression values of <100 in all samples were excluded. Multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) plots were drawn using genes that showed the coefficients of variation across samples >0.75. Differentially expressed genes were identified using the criteria of |log2(fold change)| >0.5 and q-value <5%, and submitted to DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) to acquire functional annotations by Gene-annotation enrichment analysis (GAEA), in which Gene Ontology terms with the FDR <10% were considered to be significant.

Results and Discussion

Global gene expression profiles of DP-hMSCs and AT-hMSCs

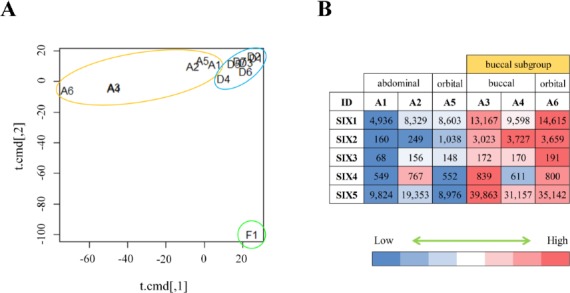

In order to compare MSCs from different tissue types, DP-hMSCs (n=7; six from exfoliated deciduous teeth and one from permanent tooth), AT-hMSCs (n=6; two from abdomen, two from buccal pad, and two from orbit) and a control sample of fibroblasts (n=1) were analyzed for their global gene expression profiles using gene expression microarrays. As shown in an MDS plot (Figure 1A), all 13 MSCs samples were grossly different from fibroblasts. Moreover, seven DP-hMSCs samples formed a tight cluster (Figure 1A; circled in blue), indicating that DP-hMSCs share very similar gene expression profiles even if they originate from independent donors.

Figure 1: Gene expression profiles of DP-hMSCs and AT-hMSCs.

A. DP-hMSCs from seven donors (D1-7; in the blue circle), AT-hMSCs from six donors (A1-6; in the orange circle), and one sample of fibroblasts (F1; in the green circle) are displayed in an MDS space. Note that the plots for A3 and A4 overlap. B. The heat map illustrates the relative expression values (high in red; low in blue) along with the readouts in each cell for sine oculis homeobox (SIX) gene family members (SIX1-5) in the six AT-hMSCs samples (A1-6).

In contrast, six AT-hMSCs samples showed diversity in the MDS plot (Figure 1A; circled in orange); samples from the abdomen (A1 and A2) and orbit (A5) were plotted in the vicinity of the tight DP-hMSCs cluster, whereas those from the buccal pad (A3 and A4) and orbit (A6) were plotted farther away from the other MSCs samples. The divergence of A3, A4 and A6 (herein named buccal subgroup) could be partly due to the complex developmental processes of cranial adipose tissue, which involves the orchestration of the neural crest and mesoderm. Consistent with this idea, sine oculis homeobox (SIX) gene family members, whose spacial and temporal expression patterns are tightly regulated during the cranial development[13], were differently expressed between the buccal subgroup and other AT-hMSCs samples (Figure 1B).

Distinct gene expression signatures in DP-hMSCs and AT-hMSCs

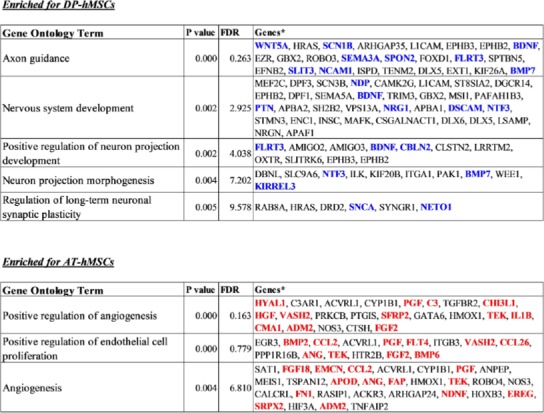

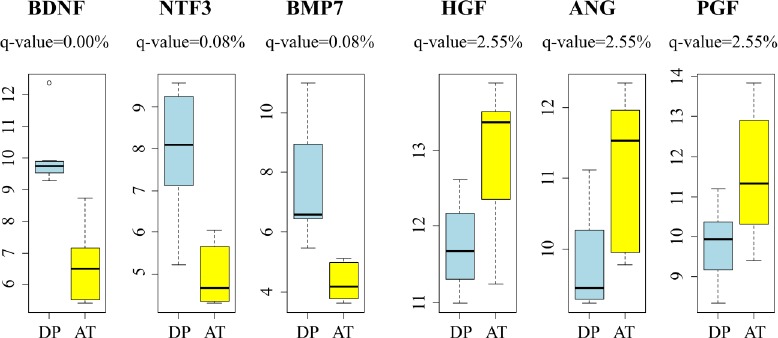

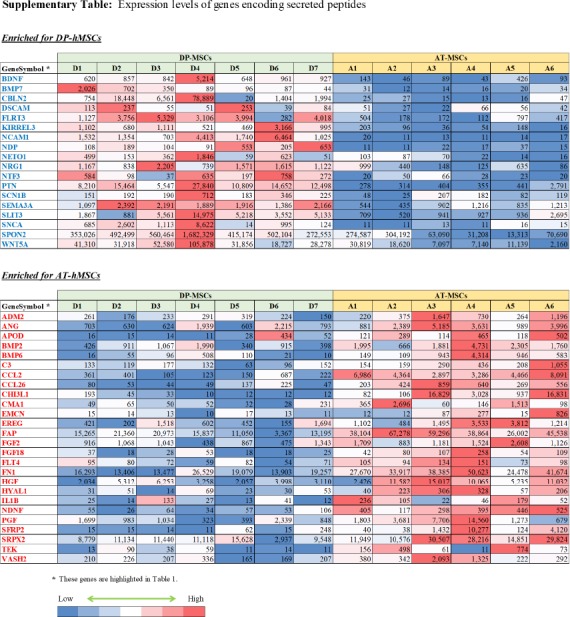

Differences between DP-hMSCs and AT-hMSCs were further investigated by identifying gene expression signatures characteristic of each group of cells using GAEA. DP-hMSCs were found to preferentially express genes involved in neuronal growth (Table 1, upper panel), consistent with the reported neurotrophic properties of DP-hMSCs[14]. Some of the signature genes encode secreted peptides, which may function as soluble neurotrophic factors when DP-hMSCs or their conditioned media are administered to patients in clinical applications (Supplementary Table). The expression levels of three representative genes for soluble neurotrophic factors (brain derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF], neurotrophin 3 [NTF3], and bone morphogenetic protein 7 [BMP7]) are presented in Figure 2. Abundant supplies of the soluble neurotrophic factors by DP-hMSCs and their conditioned media may make them attractive therapeutic tools in treating spinal cord injury, for instance, as demonstrated in animal studies[15].

Table 1: Gene-annotation enrichment analysis on DP-hMSCs and AT-hMSCs.

* Genes highlighted using blue or red letters are categorized as “secreted” for the subcellular locations in the Uni-ProtKB/Swiss-Prot database.

Figure 2: Representative genes differentially expressed between DP-hMSCs and AT-hMSCs.

Expression levels of representative genes for DP-hMSCs (n=7; DP; light blue) and AT-hMSC (n=6; AT; yellow) are displayed. Note that the y-axes indicate the log2 values of arbitrary expression readouts. The q-values are based on the SAM analysis. BDNF: brain derived neurotrophic factor; NTF3: neurotrophin 3; BMP7: bone morphogenetic protein 7; HGF: hepatocyte growth factor; ANG: angiogenin; PGF: placental growth factor.

AT-hMSCs preferentially expressed signature genes of angiogenesis (Table 1, lower panel; Supplementary Table), implying the potential therapeutic utility of AT-hMSCs to treat disorders that require an increased blood supply. Interestingly, some of the angiogenesis signature genes highly expressed in AT-hMSCs were known stimulatory factors for human hair growth. Such genes include hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)[16], angiogenin (ANG)[17], and placental growth factor (PGF)[18]; their expression levels are displayed in Figure 2. Actually, we have been using the AT-hMSCs conditioned media at hair treatment clinics to successfully treat patients with androgenetic alopecia, female pattern alopecia, and alopecia areata. It is tempting to speculate that the effective therapeutic outcomes of the conditioned media are mediated at least in part by hair growth factors encoded by these genes.

MSCs prepared from different tissue types displayed distinct molecular characteristics; DP-hMSCs demonstrated gene expression signatures of neuronal growth, while AT-hMSCs demonstrated that of angiogenesis. In designing stem cell-based therapeutic approaches, it would be reasonable to choose MSCs derived from one tissue type over others based on the gene expression characteristics. When treating cerebral infarction or spinal cord injury, for instance, DP-hMSCs should be chosen to take advantage of the neurotrophic properties. When treating ischemic limbs or hypoxia-induced disorders, on the other hand, AT-hMSCs would be a better choice. By expanding the study to MSCs from a wide range of tissue types, and by utilizing other analytical platforms such as proteomics, we can catalogue MSCs based on their molecular characteristics that are suggestive of target diseases in their clinical applications. Such studies, along with the development of bioassays to monitor the effects of MSCs, shall make it feasible to identify the MSCs most desirable for treating a disease of interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- MSCs:

Mesenchymal stem cells

- DP-hMSCs:

Human dental pulp-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- AT-hMSCs:

Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- SAM:

Significance analysis of microarrays

- MDS:

Multi-dimensional scaling

- GAEA:

Gene-annotation enrichment analysis

Potential Conflicts of Interests

None

Sponsor / Grants

Tokyo Metropolis Small and Medium Enterprise Support Center (Tokyo, Japan); Advanced Cell Technology and Engineering Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan)

Supplementary Information

References

- 1.Terunuma H, Ashiba K, Terunuma A, Deng X, Watanabe K. Conditioned medium of human immortalized mesenchymal stem cells as a novel therapeutic tool to repair damaged tissues. J Neurosci Neuroeng. 2015;4:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bang OY, Kim EH, Cha JM, Moon GJ. Adult stem cell therapy for stroke: challenges and progress. J Stroke. 2016;18(3):256–66. doi: 10.5853/jos.2016.01263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruppert KA, Nguyen TT, Prabhakara KS, Toledano Furman NE, Srivastava AK, Harting MT, Cox CS, Jr, Olson SD. Human mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles modify microglial response and improve clinical outcomes in experimental spinal cord injury. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):480–91. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18867-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lankford KL, Arroyo EJ, Nazimek K, Bryniarski K, Askenase PW, Kocsis JD. Intravenously delivered mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes target M2-type macrophages in the injured spinal cord. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jarocha D, Milczarek O, Wedrychowicz A, Kwiatkowski S, Majka M. Continuous improvement after multiple mesenchymal stem cell transplantations in a patient with complete spinal cord injury. Cell Transplant. 2015;24(4):661–72. doi: 10.3727/096368915X687796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreira A, Kahlenberg S, Hornsby P. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells for diabetes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2017;59(3):R109–R120. doi: 10.1530/JME-17-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saleh F, Itani L, Calugi S, Grave RD, El Ghoch M. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of obesity: a systematic review of longitudinal studies on preclinical evidence. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;13(6):466–75. doi: 10.2174/1574888X13666180515160008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho BS, Kim JO, Ha DH, Yi YW. Exosomes derived from human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate atopic dermatitis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):187–91. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0939-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heidari M, Pouya S, Baghaei K, Aghdaei HA, Namaki S, Zali MR, Hashemi SM. The immunomodulatory effects of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells-conditioned medium in chronic colitis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(11):8754–66. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mardpour S, Hassani SN, Mardpour S, Sayahpour F, Vosough M, Ai J, Aghdami N, Hamidieh AA, Baharvand H. Extracellular vesicles derived from human embryonic stem cell-MSCs ameliorate cirrhosis in thioacetamide-induced chronic liver injury. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(12):9330–44. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho KA, Park M, Kim YH, Woo SY, Ryu KH. RNA sequencing reveals a transcriptomic portrait of human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and palatine tonsils. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17114–22. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16788-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar A, Kumar V, Rattan V, Jha V, Pal A, Bhattacharyya S. Molecular spectrum of secretome regulates the relative hepatogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and dental tissue. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):15015–27. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14358-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fonseca BF, Couly G, Dupin E. Respective contribution of the cephalic neural crest and mesoderm to SIX1-expressing head territories in the avian embryo. BMC Dev Biol. 2017;17(1):13–27. doi: 10.1186/s12861-017-0155-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolar MK, Itte VN, Kingham PJ, Novikov LN, Wiberg M, Kelk P. The neurotrophic effects of different human dental mesenchymal stem cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12605–21. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12969-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasaki M, Radtke C, Tan AM, Zhao P, Hamada H, Houkin K, Honmou O, Kocsis JD. BDNF-hypersecreting human mesenchymal stem cells promote functional recovery, axonal sprouting, and protection of corticospinal neurons after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2009;29(47):14932–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2769-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi Y, Li M, Xu L, Chang Z, Shu X, Zhou L. Therapeutic role of human hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in treating hair loss. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2624. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou N, Fan W, Li M. Angiogenin is expressed in human dermal papilla cells and stimulates hair growth. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301(2):139–49. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0907-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon SY, Yoon JS, Jo SJ, Shin CY, Shin JY, Kim JI, Kwon O, Kim KH. A role of placental growth factor in hair growth. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74(2):125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]