Abstract

Gut microbiota is widely considered to be one of the most important components to maintain balanced homeostasis. Looking forward, probiotic bacteria have been shown to play a significant role in immunomodulation and display antitumour properties. Bacterial strains could be responsible for detection and degradation of potential carcinogens and production of short-chain fatty acids, which affect cell death and proliferation and are known as signaling molecules in the immune system. Lactic acid bacteria present in the gut has been shown to have a role in regression of carcinogenesis due to their influence on immunomodulation, which can stand as a proof of interaction between bacterial metabolites and immune and epithelial cells. Probiotic bacteria have the ability to both increase and decrease the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines which play an important role in prevention of carcinogenesis. They are also capable of activating phagocytes in order to eliminate early-stage cancer cells. Application of heat-killed probiotic bacteria coupled with radiation had a positive influence on enhancing immunological recognition of cancer cells. In the absence of active microbiota, murine immunity to carcinogens has been decreased. There are numerous cohort studies showing the correlation between ingestion of dairy products and the risk of colon and colorectal cancer. An idea of using probiotic bacteria as vectors to administer drugs has emerged lately as several papers presenting successful results have been revealed. Within the next few years, probiotic bacteria as well as gut microbiota are likely to become an important component in cancer prevention and treatment.

Introduction

Cancer is considered as one of the most significant causes of death. The treatment of tumors has received much attention in the last years; however, the number of people suffering neoplastic syndrome is still increasing. Thus, researchers are trying to face this process searching for innovative therapies and prophylaxis. Despite the fact that cancer risk indisputably depends on genetic factors, immunological condition of the organism plays a considerable role in it, that being closely associated with probiotic bacteria and commensal bacterial flora presented mainly in the digestive tract. Probiotic strains, inter alia Bifidobacterium, or Lactobacillus, widely present in commonly consumed fermented milk products, are known to have various beneficial effects on health. To date, there is a plethora of studies investigating the correlation between intestinal microbiota and carcinogenesis which have been evaluated in this article. A growing body of research has been analyzed and reviewed for the potential application of probiotics strains in prevention and treatment of cancer.

Probiotics and Cancer

Goldin and Gorbach [1] were among the first to demonstrate the association between a diet enriched with Lactobacillus and a reduced incidence of colon cancer (40% vs. 77% in controls). Probiotics have been gaining much attention due to their ability to modulate cancer cell’s proliferation and apoptosis, investigated both in vitro (Table 1) and in vivo (Table 2). Potential application of these properties in novel therapy could potentially be alternative to more invasive treatment such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Table 1.

General effects of probiotics on cancer cells in vitro

| Probiotic strain/details of experiment | Cell line | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Bifidobacterium adolescentis SPM0212 /cell free supernatant used/ |

Caco-2, HT-29, SW480 | ↓ Cell proliferation | [2] |

|

Enterococcus faecium RM11 Lactobacillus fermentum RM28 |

Caco-2 |

Cell proliferation: ↓ 21% ↓ 23% |

[3] |

|

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 |

Caco-2 | ↑ Apoptosis | [4] |

| Bacillus polyfermenticus | HT-29, DLD-1, Caco-2 |

↓ Cell proliferation N/E on apoptosis |

[5] |

|

Bacillus polyfermenticus /AOM stimulation/ |

NMC460 | ↓ Cell colony formation in cancer cells (N/E on normal colonocytes) | [5] |

|

Lactobacillus paracasei IMPC2.1 Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG /heat killed/ |

DLD-1 |

↓ Cell proliferation Induction of apoptosis |

[6] |

|

Pediococcus pentosaceus FP3, Lactobacillus salivarius FP25/FP35, Enterococcus faecium FP51 |

Caco-2 |

↓ Cell proliferation Activation of apoptosis |

[7] |

|

Lactobacillus plantarum A7 Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG /heat killed, cell free supernatant used/ |

Caco-2, HT-29 | ↓ Cell proliferation | [8] |

|

Clostridium butyricum ATCC Bacillus subtilis ATCC 9398 |

HCT116, SW1116, Caco-2 | ↓ Cell proliferation | [9] |

| Bacillus polyfermenticus KU3 | LoVo, HT-29, AGS | >90% ↓ Cell proliferation | [10] |

| Lactococcus lactis NK34 | HT-29, LoVo, AGS | >80% ↓ Cell proliferation | [11] |

| Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393 | HT29 and CT26 | Induction of apoptosis | [12] |

|

Lactobacillus pentosus B281 Lactobacillus plantarum B282 /cell free supernatant used/ |

Caco-2 and HT-29 |

↓ Cell proliferation Cell cycle arrest (G1) |

[13] |

↓ Decrease; ↑ increase; N/E no effect. Human colonic cancer cells: Caco-2, HT-29, SW1116, HCT116, SW480, DLD-1, LoVo, Human colonic epithelial cells: NMC460. Human gastric adenocarcinoma cells: AGS Mus musculus colon carcinoma cells: CT26

Table 2.

General effects of probiotics on tumor-bearing or tumor-induced animal models in vivo

| Probiotic strain | Model | Induction | Treatment | Result | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei Lactobacillus lactis biovar diacetylactis DRC-1 |

Rat | DMH | 40 weeks | ↓ TI ↓ TV ↓ TM | [14] |

| Bifidobacterium lactis KCTC 5727 | SPF C57BL rat | – | 19 weeks | ↓ TI ↓ TV | [15] |

| Bacillus polyfermenticus | CD-1 mice | DLD-1 cells injection |

20 weeks (injection) |

↓ TI ↓ TV | [5] |

| VSL#3 (Probiotics mixture) | SD rats | TNBS | 10 weeks | None of the animals developed CRC | [16] |

|

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG MTCC #1408 Lactobacillus acidophilus NCDC #1 |

SD rats | DMH | 19 weeksa | ↓ TI ↓ TM | [17] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | BALB/c mice | AOM, DSS |

Nanosized/ Live bacteria 4 weeks |

↓ TI cell cycle arrest Induction of apoptosis |

[18] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | BALB/c mice | CT26 cells injection | 14 weeks |

↓ TV Induction of necrosis |

[19] |

| VSL#3 (Probiotics mixture) | C57BL/6 mice | DSS | a | ↓ TI ↓ dysplasia | [20] |

|

Lactobacillus plantarum (AdF10) Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG |

SD rats |

DMH 4 weeks |

One of strains 12 weeks |

↓ TI ↓ TV ↓ TM | [21] |

| Lactobacillus salivarius Ren | F344 rats |

DMH 10 weeks |

2 weeksa | ↓ TI | [22] |

|

Lactobacillus acidophilus Bifidobacteria bifidum Bifidobacteria infantum |

SD rats | antibiotics DMH | 23 weeks | ↓ TI ↓ TV | [23] |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG CGMCC 1.2134 | SD rats |

DMH 10 weeks |

25 weeks |

↓ TI ↓ TV ↓ TM Induction of apoptosis |

[24] |

| Pediococcus pentosaceus GS4 | Swiss albino mice | AOM | 4 weeks |

↓ TP Induction of apoptosis |

[25] |

| Lactobacillus casei BL23 | C57BL/6 mice | DMH | 10 weeks | ↓ TI | [26] |

aBefore and until the end of experiment

↓ Decrease, TI tumor incidence, TV tumor volume, TM tumor multiplicity, TP tumor progression, AOM azoxymethane, CRC colorectal cancer, DMH 1,2 dimethylhydrazine dihydrochloride, DSS dextran sulfate sodium, TNBS trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid, SD rat Sprague–Dawley rat

Mechanisms of Action

A specific mechanism associated with antitumor properties of probiotics remains unclear. Gut microbiota is engaged in a variety of pathways, which are considered to play a central role in that process. Primarily, probiotic bacteria play an essential role in the preservation of homeostasis, maintaining sustainable physicochemical conditions in the colon. Reduced pH caused inter alia by the excessive presence of bile acids in feces may be a direct cytotoxic factor affecting colonic epithelium leading to colon carcinogenesis [27, 28]. Regarding their involvement in the modulation of pH and bile acid profile, probiotic bacteria such as L. acidophilus and B. bifidum have been demonstrated to be a promising tool in cancer prevention [27, 29, 30].

Probiotic strains are also responsible for maintaining the balance between the quantity of other participants of natural intestinal microflora and their metabolic activity. Putrefactive bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Clostridium perfringens naturally present in the gut, has been proven to be involved in production of carcinogenic compounds using enzymes like b-glucuronidase, azoreductase, and nitroreductase. Some preliminary research conducted by Goldin and Gorbach in the late 1970s have proven consumption of milk fermentation products to have a beneficial effect on the increase in the number of L. acidophilus in rat’s gut, which subsequently resulted in a reduction of putrefactive bacteria and decrease in the level of harmful enzymes [31]. Several subsequent studies confirmed the positive influence of the probiotic strains on the activity of bacterial enzymes implicated in the tumor genesis both in humans [32, 33] and rodents [1, 31, 34–38]. It is worth noting that there is considerable ambiguity among the gathered data; nevertheless, results concerning glucuronidase and nitroreductase are in general consistent. However, whether these processes affect cancer rates in humans is yet to be investigated [39].

Another cancer-preventing strategy involving probiotic bacteria, chiefly Lactobacillus and Bifidobacillus strains, could be linked to the binding and degradation of potential carcinogens. Mutagenic compounds associated with the increased risk of colon cancer are commonly found in unhealthy food, especially fried meat. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain by human volunteers alleviated the mutagenic effect of diet rich in cooked meat, which resulted in a decreased urinary and fecal excretion of heterocyclic aromatic amines (HAAs) [40, 41]. Supplementation with dietary lactic acid bacteria has shown to downregulate the uptake of 3-amino-1-methyl-5H-pyrido (4,3-β) indole (Trp-P-2) and its metabolites in mice [42]. Furthermore, many in vitro studies have been conducted, demonstrating the ability of different probiotics strains to either bind [43–51] or metabolize [43, 47, 49] mutagenic compounds such as HAAs [44–47, 49, 50], nitrosamines [43, 49], aflatoxin B1 [48], and others: mycotoxins, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and phthalic acid esters (PAEs) [52]. In some cases investigation revealed the correlation of these properties with the reduction of mutagenic activities presented by the aforementioned compounds [43, 45–47, 50, 53]. It is worth highlighting that the substantial part of a current knowledge on the phenomenon discussed above is largely based on in vitro studies. All these results should be interpreted with caution, according to the variations of factors such as pH, occurring at in vivo conditions, which can potentially alter the efficiency of binding or degradation of the mutagens [52].

Many beneficial compounds produced and metabolized by gut microbiota have been demonstrated to play an essential role in maintaining homeostasis and suppressing carcinogenesis. Specific population of gut microbiota are dedicated to production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate as a result of the fermentation of fiber-rich prebiotics. Except for their principal function as an energy source, SCFA have also been proven to act as signaling molecules affecting the immune system, cell death, and proliferation [54] as well as the intestinal hormone production and lipogenesis, which explains their crucial role in epithelial integrity maintenance [55].

Although lactic acid bacteria are not directly involved in SCFA production, certain probiotic strains of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli can modulate the gut microbiota composition and consequently affect the production of SCFA [56]. Butyrate, produced by species belonging to the Firmicutes families (Ruminococcaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Clostridiaceae) [55] has been proven to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation in cancer cells cultured in vitro [57] and remains the most investigated of SCFAs. Colorectal cancer is strongly correlated with decreased levels of SCFA and SCFA-producing bacteria dysbiosis [58]. Administration of bacterial strain Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens MDT-1, (known for their high production of butyrate) in mouse model of colon cancer, inhibited progression of tumor development, affecting also the reduction of β-glucuronidase and increasing the immune response [59].

More recent evidence suggests modulation of SCFA-producing bacteria by dietary intervention with fermentable fibers as a possible colorectal cancer treatment. A more recent study on mice demonstrated amelioration of polyposis in CRC (colorectal cancer) after increasing SCFA-producing bacteria after introduction of probiotic diet. Previously investigated application of synbiotic combination of B. lactis and resistant starch in rat-azoxymethane model has been proven to protect against the development of CRC, which was correlated with increased SCFA production [60]. Interestingly, neither B. lactis nor prebiotic were sufficient to achieve that effect alone. This and some previous assays suggest that prebiotic activity of fiber-enriched diet, projecting on the level of beneficial bacteria, is promising strategy to prevent CRC.

Lactic acid bacteria have been receiving much attention due to its contribution to immunomodulation correlated with either suppression or regression of carcinogenesis. This phenomenon is the result of multidimensional activity involving interaction between the bacteria or their metabolites with the immune and epithelial cells [9, 19, 61–63]. Consequentially, probiotic strains have the ability to both increase and decrease the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines as well as modulate secretion of prostaglandins, which altogether projects on suppression of carcinogenesis. Another strategy involves activation of phagocytes by certain probiotic strains, leading to direct elimination of early-stage cancer cells [58, 62]. For a detailed review, see a comprehensive elaboration recently published in Nature summarizing the mechanisms engaging microbiota in immune homeostasis and disease [64].

It has been demonstrated that some probiotics strains of Lactobacilli have been proven to suppress gastric-cancer-related H. pylori infections [65–67]. Another study conducted on patients with persistent human papillomavirus virus (HPV) showed an enhanced clearance of HPV and cervical cancer precursors after daily consumption of probiotics for 6 months [68].

Probiotics in Cancer Therapy

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the possible application of probiotics as a part of combination therapy with conventional treatment of cancer. An early but controlled and comparative study on 223 patients carried out in 1993 showed that combination therapy including radiation and treatment with heat-killed L. casei strains (LC9018) and improved the induction of immune response mechanisms against cancer cells thereby enhancing tumor regression in patients with carcinoma of the uterine cervix [69]. Research on azoxymethane-induced CRC mice model treated by the probiotic mix composed of seven different strains of lactobacilli, bifidobacteria, and streptococcus demonstrated suppression of colon carcinogenesis due to modulation of mucosal CD4+ T polarization and changes in the gene expression [70]. Furthermore, latest experiment investigating the effects of B. infantis administration in CRC rat model demonstrated a considerable attenuation of chemotherapy-induced intestinal mucositis correlated with decreased level on proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) and increased CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T regulatory cell response [71].

Over and above that, two seminal papers published in Science highlighted the significant role played by gut microbiota in the immune response to cancer treatment. Disruption of the microbiota in mice was made evident by a decreased immune response and thereby tumor resistance for either cyclophosphamide [72] or oxaliplatin therapy [73]. As a result of these findings, probiotic bacteria have been gaining traction as a crucial component in successful cancer immunotherapy [63, 74–76].

The most recent experiments on mice have illustrated the key role of gut microbiota (Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium) in anti-PD-L1 (Programmed death-ligand 1) and anti-CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4) therapies [77, 78]. Immunomodulatory effect was exhibited in intensified activation of dendritic cells and also promotion of antitumor T cell response. Essentially, Sivan et al. [77] observed a similar improvement of tumor control as a result of Bifidobacterium treatment alone compared to anti–PD-L1 therapy, whereas combination of both strategies was sufficient to nearly eliminate tumor outgrowth. These groundbreaking results indicate that administration of probiotics appears to be a promising strategy in maximizing the efficiency of cancer immunotherapy.

Cohort Studies

Several cohort studies have revealed the correlation between the consumption of dairy products and the risk of colon cancer. Some of these findings appear useful in drawing conclusions concerning the role of probiotic bacteria in carcinogenesis, taking into account certain groups of previously investigated dairy products such as fermented milk products with a special emphasis on yogurt. There is still considerable ambiguity among studies, summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cohort studies investigating the correlation between the consumption of dairy products and the cancer risk

| Study | Country | Years | No. of participants | Products | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Järvinen (2001) [79] | Finland | 1966–1972 | 9959 | Milk and dairy products | I/Aa |

| van’t Veer (1994) [80] | United states | 1986–1989 | 120,852 | Fermented dairy products | Slight I/A |

| Kearney (1996) [81] | United states | 1986–1992 | 47,935 | Milk and fermented dairy products | N/S/A |

| Pietinen (1999) [82] | Finland | End 1993 | 27,111 | Milk and dairy products | I/A |

| Lin (2005) [83] | United States | 1993 | 39,876 | Milk fermented and unfermented dairy products | N/S/A |

| Larsson (2006) [84] | Sweden | 1997–2004 | 45,306 | Dairy products | I/A |

aWithout specific effects of fermented milk

I/A inversed associations between intake and cancer risk N/S/A no significant associations

In contrast to that uncertainty, a recent study conducted in 2012 produced a meta-analysis including nineteen cohort studies which demonstrated an association between consumption of dairy products (except cheese) and a decreased colorectal cancer risk [85]. Another noteworthy approach investigating the influence of dairy products on post-diagnostic CRC survival clearly indicates positive correlation between the high dairy intake and the lower risk of death [86].

A key problem with the majority of the cohort studies mentioned above is that they covered general dairy intake, including high-fat components such as cream and cheese, suspected of carcinogenic properties due to their ability to increase bile acid levels in the colon [85, 87]. Moreover, research tends to focus on anticancer compounds such as calcium or vitamin D, without paying special attention to probiotics. Therefore, the first innovative cohort study conducted in 2011 by Pala et al. [88] on 45,241 subjects proved a significant association between single probiotic-rich product intake (yogurt) and decreased colon cancer risk. Similar approaches should be conducted on large cohorts, investigating probiotics’ intake from natural sources (such as yogurt and other fermented dairy products) as well as supplements, in order to reveal their effect on cancer risk.

Probiotics in Treatment and Prophylaxis

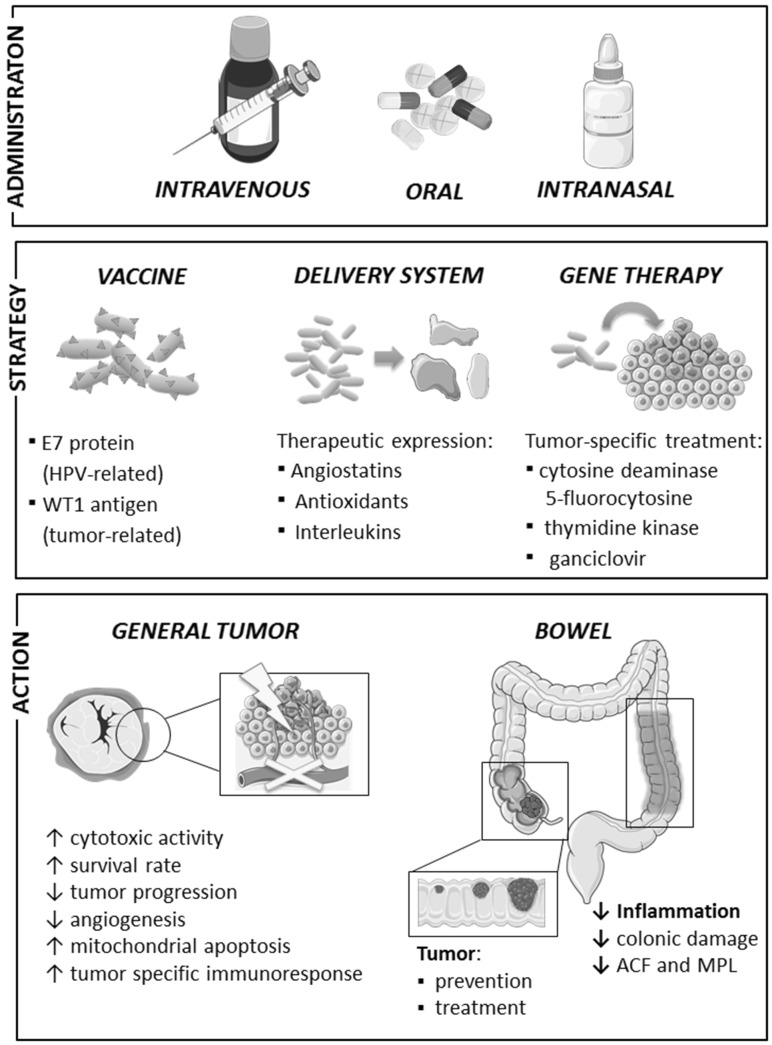

Utilization of the recombinant probiotic strains as a delivery system for various therapeutic molecules such as drugs, as well as cytokines, enzymes, or even DNA [89, 90] is quite recent and exceptional idea that could be successfully applied for colorectal cancer treatment (Fig. 1). Probiotic bacteria are indispensable as vectors due to their wide range of tolerance to the environment of gastrointestinal tract co-occurring with their natural capability of colonizing the mucosal surface followed by prolonged residence maintaining their protective properties [91]. The innovative concept of a “bio drug” relies on oral administration of genetically modified probiotics allowing a direct delivery of the therapeutic components to the intestinal mucosa. Regarding low costs, simple technology, and procedure of the treatment, this strategy has a great potential to be widely used in prevention and treatment of various disorders.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the possible applications of probiotic bacteria in the treatment and prevention of cancer. Figure summaries most significant findings from studies in vitro and in vivo mentioned in text [89–114]. This figure was prepared using Servier Medical Art, available from www.servier.com/Powerpoint-image-bank. Legend: downwards arrow decrease, upwards arrow increase ACF aberrant crypt foci, MPL multiple plaque lesions

In several independent studies on rodents, intragastric application of recombinant strains of Lactobacillus lactis expressing anti-inflammatory compounds (cytokines, IL-10, human interferon-beta, or antioxidants) has been shown to ameliorate the intestinal inflammation and demonstrated cytoprotective effect [92–94]. In another approach, application of Lactococcus lactis expressing catalase has been proven to decrease the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as H2O2, reducing colonic damage, and inflammation, consequently projecting on tumor invasion and proliferation [95].

More recent study investigating multiple strategies of inhibition of the inflammatory-related carcinogenesis with different combination of probiotic vectors expressing antioxidant enzymes (catalase, superoxide dismutase) or IL-10 (produced as cDNA or in expression system inducible by stress—SICE) has shown these strains as agents causing significant changes of the immune response as well as pre-neoplastic lesions or even causing the entire inhibition of tumor development [96] (for details see Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of the strategies using the probiotic strains in cancer prevention and treatment

| Probiotic strains | Model | Treatment | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotic vaccination | ||||

| Lactococcus lactis |

C57BL/6 mice → Intranasal |

E7 protein displayed | ↑ Antitumor effect of following Ad-CRT-E7 treatment | [104] |

| Lactococcus lactis |

C57BL/6 mice → Intranasal |

E7 protein displayed | HPV-16 E7-specific immune response | [103] |

| Bifidobacterium longum |

C57BL/6N mice inj/w C1498-WT1 → Oral |

WT1 displayed |

↓ WT1-expressing Tumor growth ↑ Survival rate ↑ Tumor infiltration of CD4+ T and CD8+ T ↑ Cytotoxic activity |

[96] |

| Mitigation of inflammation | ||||

|

Streptococcus thermophilus Lactococcus lactis |

BALB/c mice (DMH)-I CRC → Oral |

Antioxidant enzymes (catalase, superoxide dismutase), IL-10; Groups: IL-10 (SICE) IL-10 (cDNA) antioxidants, mix |

All groups: ↓ Tumor incidence ↓ ACF and MPL ↓ MCP-1 ↑ IL-10/TNFα Groups: IL 10 (SICE), antioxidants and mix: no tumor Mix: ↓↓ ACF and MPL ↓↓ MCP-1 ↑↑ IL-10/TNFα |

[96] |

| Lactococcus lactis |

DSS-induced mice → Intragastric |

IL-10 |

No tumor ↓ Colonic damage ↓ Inflammation |

[92] |

| Lactococcus lactis |

BALB/c mice (DMH)-I CRC → Oral |

Catalase |

↓ Colonic damage ↓ Inflammation ↓ Tumor incidence ↓ Tumor progression |

[95] |

| Drug delivery | ||||

| Bifidobacterium longum |

BALB/c mice inj/w CT24 → Oral or injection |

Tumstatin | Antitumor effect | [111] |

| Lactococcus lactis |

Rats (DMH)-I CRC → Oral |

Endostatin |

↑ Survival rate N/E on complete cure |

[115] |

| Bifidobacterium longum |

C57BL/6 mice inj/w Lewis lung cancer and B16-F10 → Oral |

Endostatin or endostatin + selenium |

Endostatin group: ↓ Tumor progression ↑ Survival time Endostatin ± selenium: ↓↓ Tumor progression ↑ Activity of NK, T cells and ↑ Activity of IL-2 and TNF-a i |

[112] |

| Gene therapy | ||||

| Bifidobacterium infantis |

Melanoma B16-F10 cells → Supernatant fluid |

Cytosine deaminase/5-fluorocytosine |

↑ Morphological damage ↓ Growth |

[116] |

|

C57BL/6 Mice, inj/w B16-F10 cells → Injection |

Cytosine deaminase/5-fluorocytosine | Antitumor effect | ||

| Bifidobacterium infantis |

BALB/c Mice and cell lines: Colo320, MKN-45, SSMC-7721, MDA-MB-231 → Injection |

Thymidine kinase (BF-rTK) Ganciclovir (GCV) |

↑ Mitochondrial apoptosis ↓ Inflammation ↓ TNFα |

[113] |

→ Administration, inj/w injected with, ↓ decrease, ↑ increase, N/E no effect. Cell lines: human: Colo320—colon adenocarcinoma MKN-45—gastric cancer, MDA-MB-231—breast cancer, SSMC-7721—liver cancer. Mouse: B16-F10—skin melanoma, CT24—colorectal cancer, C1498-WT1—leukemia

ACF and MPL pre-neoplastic lesion: aberrant crypt foci and multiple plaque lesions, CRC colorectal cancer, DMH-I 2-dimethylhydrazine induced, DSS dextran sulfate sodium, HO-1 Heme oxygenase-1, IL-10 interleukin 10, MCP-1 monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (cytokine), MT mammary tumor, S–D Sprague–Dawley (rats), TNFα tumor necrosis factor

A plethora of studies reported potential application of the probiotic expression systems as vaccines, demonstrating stimulation of the adaptive immune system response against the pathogens [97–99]. A number of experiments investigating application of genetically engineered probiotics expressing human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein or the treatment of cervical cancer have shown that in contrast to the traditional polyvalent vaccines, which have preventive properties only on the development of the disease, “probiotic vaccination” has been demonstrated to have both protective (stimulating immunological response) and therapeutic effects (tumor regression) [100–103]. Pre-immunization with E7-displaying lactococci significantly enhanced the antitumor effect of a following treatment with adenovirus [104].

Studies on TC-1 tumor murine model have shown that therapeutic effect can be enhanced by co-administration of Lactobacillus lactis capable of expressing oncoprotein E7 and immunostimulatory compounds, such as interleukin-12 [96, 101, 102]. Prophylactic administration of the vaccine in healthy individuals conferred to resistance to subsequent administration of lethal levels of tumor cell line TC-1, even after the second induction, resulting in 80 [102] to 100% [101] survival rate. Treatment of tumor-bearing mice with recombined probiotic caused regression of palpable tumors, correlated with the increased antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) immunoresponse [101, 102].

Most recent evidence proposes the utilization of probiotics in the delivery of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) as an orally administrated vaccine, based on a recently reported prosperous approach with Bifidobacterium expressing Wilms’ tumor 1 (WT1) protein [105].

Occurrence of hypoxic and neurotic areas among solid cancer tissues gives rise to the opportunity of utilization of a specific tendency of certain probiotic strains for selective localization and proliferation in anaerobic environment [106–109]. This phenomenon was further investigated in rodents, leading to the evaluation of direct anticancer treatment using Bifidobacteria as a delivery vehicle for specific drugs such as cytosine deaminase [110] or angiostatins [111, 112] or even in gene therapy [113].

The most important limitation of abovementioned strategies lies in the fact that genes for antibiotic resistance, commonly used as selective marker in the procedure of cloning, could be potentially transferred to resident intestinal microbiota by probiotic delivery vectors. Finding an alternative, secure selection marker for cloning in therapeutic strains still remains a challenging area in this field [114].

Conclusions

This paper has given an account of the role played by gut microbiota in cancer prevention and treatment. It is noteworthy that until now most of these innovative methods mentioned above have only been investigated in animal models. Clinical tests of this strategy are expected to raise a possibility of utilizing probiotic bacteria as comprehensive drug-delivery vectors for non-invasive cancer treatment in humans. Taken together, a growing body of literature had highlighted a role of probiotic balance in maintenance of widely understood homeostasis, projecting on successful cancer therapy. The evidence from latest studies points towards the idea of possible implementation of probiotics in cutting-edge cancer therapies. Future investigations on the current topic are therefore necessary in order to validate these findings and establish therapeutic strategies. This could conceivably lead to a breakthrough in various fields of medicine not only supporting immunotherapy in cancer treatment or elaboration and production of an innovative vaccines, but also improving drug delivery in other bowel diseases while preventing and mitigating inflammation at the same time.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. E. Przydatek and Mr Jack Cordova for help with the correction of the English language in the manuscript.

Author Contributions

AG selected the scope of the article and did primary literature review. AG, DP, and MN wrote the manuscript. DP and MN contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The publication of this paper is realized with the financial support by “Najlepsi z Najlepszych 3.0” PO WER (2014–2020) program founded by Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Goldin BR, Gorbach SL. Effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus dietary supplements on 1,2-dimethylhydrazine dihydrochloride-induced intestinal cancer in rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980;64:263–265. doi: 10.1093/jnci/64.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y, Lee D, Kim D, et al. Inhibition of proliferation in colon cancer cell lines and harmful enzyme activity of colon bacteria by Bifidobacterium adolescentis SPM0212. Arch Pharm Res. 2008;31:468–473. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1180-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thirabunyanon M, Boonprasom P, Niamsup P. Probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented dairy milks on antiproliferation of colon cancer cells. Biotechnol Lett. 2009;31:571–576. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9902-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altonsy MO, Andrews SC, Tuohy KM. Differential induction of apoptosis in human colonic carcinoma cells (Caco-2) by Atopobium, and commensal, probiotic and enteropathogenic bacteria: mediation by the mitochondrial pathway. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;137:190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma EL, Choi YJ, Choi J, et al. The anticancer effect of probiotic Bacillus polyfermenticus on human colon cancer cells is mediated through ErbB2 and ErbB3 inhibition. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:780–790. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orlando A, Refolo MG, Messa C, et al. Antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects of viable or heat-killed Lactobacillus paracasei IMPC2.1 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in HGC-27 gastric and DLD-1 colon cell lines. Nutr Cancer. 2012;64:1103–1111. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.717676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thirabunyanon M, Hongwittayakorn P. Potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria of human origin induce antiproliferation of colon cancer cells via synergic actions in adhesion to cancer cells and short-chain fatty acid bioproduction. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2013;169:511–525. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9995-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadeghi-Aliabadi H, Mohammadi F, Fazeli H, Mirlohi M. Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum A7 with probiotic potential on colon cancer and normal cells proliferation in comparison with a commercial strain. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2014;17:815–819. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z-F, Ai L-Y, Wang J-L, et al. Probiotics Clostridium butyricum and Bacillus subtilis ameliorate intestinal tumorigenesis. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:1433–1445. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee NK, Son SH, Jeon EB, et al. The prophylactic effect of probiotic Bacillus polyfermenticus KU3 against cancer cells. J Funct Foods. 2015;14:513–518. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han KJ, Lee NK, Park H, Paik HD. Anticancer and anti-inflammatory activity of probiotic Lactococcus lactis nk34. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;25:1697–1701. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1503.03033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tiptiri-Kourpeti A, Spyridopoulou K, Santarmaki V, et al. Lactobacillus casei exerts anti-proliferative effects accompanied by apoptotic cell death and up-regulation of TRAIL in colon carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2016 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saxami G, Karapetsas A, Lamprianidou E, et al. Two potential probiotic lactobacillus strains isolated from olive microbiota exhibit adhesion and anti-proliferative effects in cancer cell lines. J Funct Foods. 2016;24:461–471. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arvind Singh NK, Sinha PR. Inhibition of 1,2 dimethylhydrazine induced genotoxicity in rats by the administration of probiotic curd. Int J Probiotics Prebiotics. 2009;4:201–203. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SW, Kim HM, Yang KM, et al. Bifidobacterium lactis inhibits NF-κB in intestinal epithelial cells and prevents acute colitis and colitis-associated colon cancer in mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1514–1525. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Appleyard CB, Cruz ML, Isidro AA, et al. Pretreatment with the probiotic VSL#3 delays transition from inflammation to dysplasia in a rat model of colitis-associated cancer. Am J Physiol Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G1004–G1013. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00167.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verma A, Shukla G. Synbiotic (Lactobacillus rhamnosus + Lactobacillus acidophilus + inulin) attenuates oxidative stress and colonic damage in 1,2 dimethylhydrazine dihydrochloride-induced colon carcinogenesis in Sprague’ Dawley rats: a long-term study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23:550–559. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HA, Kim H, Lee K-W, Park K-Y. Dead nano-sized Lactobacillus plantarum inhibits azoxymethane/dextran sulfate sodium-induced colon cancer in Balb/c mice. J Med Food. 2015;18:1400–1405. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2015.3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J, Wang C, Ye L, et al. Anti-tumour immune effect of oral administration of Lactobacillus plantarum to CT26 tumour-bearing mice. J Biosci. 2015;40:269–279. doi: 10.1007/s12038-015-9518-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talero E, Bolivar S, Ávila-Román J, et al. Inhibition of chronic ulcerative colitis-associated adenocarcinoma development in mice by VSL#3. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1027–1037. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walia S, Kamal R, Kanwar SS, Dhawan DK. Cyclooxygenase as a target in chemoprevention by probiotics during 1,2-dimethylhydrazine induced colon carcinogenesis in rats. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67:603–611. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2015.1011788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang M, Fan X, Fang B, et al. Effects of Lactobacillus salivarius Ren on cancer prevention and intestinal microbiota in 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine-induced rat model. J Microbiol. 2015;53:398–405. doi: 10.1007/s12275-015-5046-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuugbee ED, Shang X, Gamallat Y, et al. Structural change in microbiota by a probiotic cocktail enhances the gut barrier and reduces cancer via TLR2 signaling in a rat model of colon cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2908–2920. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gamallat Y, Meyiah A, Kuugbee ED, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus induced epithelial cell apoptosis, ameliorates inflammation and prevents colon cancer development in an animal model. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;83:536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubey V, Ghosh AR, Bishayee K, Khuda-Bukhsh AR. Appraisal of the anti-cancer potential of probiotic Pediococcus pentosaceus GS4 against colon cancer: in vitro and in vivo approaches. J Funct Foods. 2016;23:66–79. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenoir M, del Carmen S, Cortes-Perez NG, et al. Lactobacillus casei BL23 regulates Tregand Th17 T-cell populations and reduces DMH-associated colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:862–873. doi: 10.1007/s00535-015-1158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia W, Xie G, Jia W. Bile acid–microbiota crosstalk in gastrointestinal inflammation and carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernstein H, Bernstein C, Payne CM, et al. Bile acids as carcinogens in human gastrointestinal cancers. Mutat Res. 2005;589:47–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biasco G, Paganelli GM, Brandi G, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum on rectal cell kinetics and fecal pH. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1991;23:142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lidbeck A, Allinger UG, Orrhage KM, et al. Impact of Lactobacillus acidophilus supplements on the faecal microflora and soluble faecal bile acids in colon cancer patients. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 1991;4:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldin B, Gorbach SL. Alterations in fecal microflora enzymes related to diet, age, lactobacillus supplements, and dimethylhydrazine. Cancer. 1977;40:2421–2426. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197711)40:5+<2421::aid-cncr2820400905>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim DHDH, Jin YHYH. Intestinal bacterial beta-glucuronidase activity of patients with colon cancer. Arch Pharm Res. 2001;24:564–567. doi: 10.1007/BF02975166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldin BR, Swenson L, Dwyer J, et al. Effect of diet and Lactobacillus acidophilus supplements on human fecal bacterial enzymes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980;64:255–261. doi: 10.1093/jnci/64.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorbach SL. The relationship between diet and rat fecal bacterial enzymes implicated in colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;57:371–375. doi: 10.1093/jnci/57.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldin BR, Gorbach SL. Alterations of the intestinal microflora by diet, oral antibiotics, and lactobacillus: decreased production of free amines from aromatic nitro compounds, azo dyes, and glucuronides. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;73:689–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kulkarni N, Reddy BS. Inhibitory effect of Bifidobacterium iongum cultures on the azoxymethane-induced aberrant crypt foci formation and fecal bacterial -glucuronidase. Exp Biol Med. 1994;207:278–283. doi: 10.3181/00379727-207-43817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowland IR, Rumney CJ, Coutts JT, Lievense LC. Effect of Bifidobacterium longum and inulin on gut bacterial metabolism and carcinogen-induced aberrant crypt foci in rats. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:281–285. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh J, Rivenson A, Tomita M, et al. Bifidobacterium longum, a lactic acid-producing intestinal bacterium inhibits colon cancer and modulates the intermediate biomarkers of colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:833–841. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.4.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirayama K, Rafter J. The role of probiotic bacteria in cancer prevention. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:681–686. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lidbeck A, Övervik E, Rafter J, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus supplements on mutagen excretion in faeces and urine in humans. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 1992;5:59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayatsu H, Hayatsu T. Suppressing effect of Lactobacillus casei administration on the urinary mutagenicity arising from ingestion of fried ground beef in the human. Cancer Lett. 1993;73:173–179. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(93)90261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orrhage KM, Annas A, Nord CE, et al. Effects of lactic acid bacteria on the uptake and distribution of the food mutagen Trp-P-2 in mice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:215–221. doi: 10.1080/003655202753416902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nowak A, Kuberski S, Libudzisz Z. Probiotic lactic acid bacteria detoxify N-nitrosodimethylamine. Food Addit Contam Part A. 2014;31:1678–1687. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2014.943304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faridnia F, Hussin ASM, Saari N, et al. In vitro binding of mutagenic heterocyclic aromatic amines by Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum G4. Benef Microbes. 2010;1:149–154. doi: 10.3920/BM2009.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stidl R, Sontag G, Koller V, Knasmüller S. Binding of heterocyclic aromatic amines by lactic acid bacteria: results of a comprehensive screening trial. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:322–329. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orrhage K, Sillerström E, Gustafsson JÅ, et al. Binding of mutagenic heterocyclic amines by intestinal and lactic acid bacteria. Mutat Res Regul Pap. 1994;311:239–248. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nowak A, Libudzisz Z. Ability of probiotic Lactobacillus casei DN 114001 to bind or/and metabolise heterocyclic aromatic amines in vitro. Eur J Nutr. 2009;48:419–427. doi: 10.1007/s00394-009-0030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peltonen KD, El-Nezami HS, Salminen SJ, Ahokas JT. Binding of aflatoxin B1 by probiotic bacteria. J Sci Food Agric. 2000;80:1942–1945. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duangjitcharoen Y, Kantachote D, Prasitpuripreecha C, et al. Selection and characterization of probiotic lactic acid bacteria with heterocyclic amine binding and nitrosamine degradation properties. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2014;4:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nowak A, Czyżowska A, Stańczyk M. Protective activity of probiotic bacteria against 2-amino-3-methyl-3H-imidazo[4,5-f]quinoline (IQ) and 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) – an in vitro study. Food Addit Contam. 2015;32:1927–1938. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2015.1084651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nowak A, Ślizewska K, Błasiak J, Libudzisz Z. The influence of Lactobacillus casei DN 114 001 on the activity of faecal enzymes and genotoxicity of faecal water in the presence of heterocyclic aromatic amines. Anaerobe. 2014;30:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lili Z, Junyan W, Hongfei Z, et al. Detoxification of cancerogenic compounds by lactic acid bacteria strains. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;0:1–16. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2017.1339665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Commane D, Hughes R, Shortt C, Rowland I. The potential mechanisms involved in the anti-carcinogenic action of probiotics. Mutat Res. 2005;591:276–289. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garret WS. Cancer and the microbiota. Science. 2015;348:80–86. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Requena T, Martinez-Cuesta MC, Peláez C. Diet and microbiota linked in health and disease. Food Funct. 2018 doi: 10.1039/c7fo01820g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.LeBlanc JG, Chain F, Martín R, et al. Beneficial effects on host energy metabolism of short-chain fatty acids and vitamins produced by commensal and probiotic bacteria. Cell Fact: Microb; 2017. p. 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fotiadis CI, Stoidis CN, Spyropoulos BG, Zografos ED. Role of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in chemoprevention for colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6453–6457. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dos Reis SA, da Conceição LL, Siqueira NP, et al. Review of the mechanisms of probiotic actions in the prevention of colorectal cancer. Nutr Res. 2017;37:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ohkawara S, Furuya H, Nagashima K, et al. Oral administration of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens, a butyrate-producing bacterium, decreases the formation of aberrant crypt foci in the colon and rectum of mice. J Nutr. 2005;135:2878–2883. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.12.2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le Leu RK, Hu Y, Brown IL, et al. Synbiotic intervention of Bifidobacterium lactis and resistant starch protects against colorectal cancer development in rats. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:246–251. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ivanov II, Honda K. Intestinal commensal microbes as immune modulators. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:496–508. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Delcenserie V, Martel D, Lamoureux M, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of probiotics in the intestinal tract. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2008;10:37–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pitt JM, Vétizou M, Waldschmitt N, et al. Fine-tuning cancer immunotherapy: optimizing the gut microbiome. Cancer Res. 2016;76:4602–4607. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Honda K, Littman DR. The microbiota in adaptive immune homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2016;535:75–84. doi: 10.1038/nature18848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuo CH, Kuo CH, Wang SSW, et al. Long-term use of probiotic-containing yogurts is a safe way to prevent Helicobacter pylori: based on a Mongolian Gerbil’s model. Biochem Res Int. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/594561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen X, Liu XM, Tian F, et al. Antagonistic activities of Lactobacilli against Helicobacter pylori growth and infection in human gastric epithelial cells. J Food Sci. 2012;77:9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oh Y, Osato MS, Han X, et al. Folk yoghurt kills Helicobacter pylori. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;93:1083–1088. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Verhoeven V, Renard N, Makar A, et al. Probiotics enhance the clearance of human papillomavirus-related cervical lesions: a prospective controlled pilot study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2013;22:46–51. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328355ed23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Okawa T, Niibe H, Arai T, et al. Effect of LC9018 combined with radiation therapy on carcinoma of the uterine cervix. A phase III, multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Cancer. 1993;72:1949–1954. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930915)72:6<1949::aid-cncr2820720626>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bassaganya-Riera J, Viladomiu M, Pedragosa M, et al. Immunoregulatory mechanisms underlying prevention of colitis-associated colorectal cancer by probiotic bacteria. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mi H, Dong Y, Zhang B, et al. Bifidobacterium infantis ameliorates chemotherapy-induced intestinal mucositis via regulating T cell immunity in colorectal cancer rats. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;42:2330–2341. doi: 10.1159/000480005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Viaud S, Saccheri F, Mignot G, et al. The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide. Science. 2013;342:971–976. doi: 10.1126/science.1240537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iida N, Dzutsev A, Stewart CA, et al. Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Science. 2013;342:967–970. doi: 10.1126/science.1240527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Poutahidis T, Kleinewietfeld M, Erdman SE. Gut microbiota and the paradox of cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2014;5:157. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.West NR, Powrie F. Immunotherapy not working? Check your microbiota. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:687–689. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wan MLY, El-Nezami H. Targeting gut microbiota in hepatocellular carcinoma: probiotics as a novel therapy. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2018;7:11–20. doi: 10.21037/hbsn.2017.12.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science. 2015;350:1084–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vétizou M, Pitt JM, Daillère R, et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science. 2015;350(6264):1079–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Järvinen R, Knekt P, Hakulinen T, Aromaa A. Prospective study on milk products, calcium and cancers of the colon and rectum. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55:1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van’t Veer P, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA, van’t Veer P. Fermented dairy products, calcium, and colorectal cancer in the Netherlands Cohort Study. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3186–3190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kearney J, Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, et al. Calcium, vitamin D, and dairy foods and the occurrence of colon cancer in men. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:907–917. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pietinen P, Malila N, Virtanen M, et al. Diet and risk of colorectal cancer in a cohort of Finnish men. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:387–396. doi: 10.1023/a:1008962219408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lin J, Zhang SM, Cook NR, et al. Intakes of calcium and vitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:755–764. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Larsson SC, Bergkvist L, Rutegård J, et al. Calcium and dairy food intakes are inversely associated with colorectal cancer risk in the Cohort of Swedish Men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:667–673. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.83.3.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Aune D, Lau R, Chan DSM, et al. Dairy products and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:37–45. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang B, McCullough ML, Gapstur SM, et al. Calcium, vitamin D, dairy products, and mortality among colorectal cancer survivors: the cancer prevention study-II nutrition cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2335–2343. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Narisawa T, Reddy BS, Weisburger JH. Effect of bile acids and dietary fat on large bowel carcinogenesis in animal models. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1978;13:206–212. doi: 10.1007/BF02773665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pala V, Sieri S, Berrino F, et al. Yogurt consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in the Italian European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition cohort. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2712–2719. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sleator RD, Hill C. Battle of the bugs. Science. 2008;321:1294–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.321.5894.1294b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wells J. Mucosal vaccination and therapy with genetically modified lactic acid bacteria. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2011;2:423–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-022510-133640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Amalaradjou MAR, Bhunia AK. Bioengineered probiotics, a strategic approach to control enteric infections. Bioengineered. 2013;4:379–387. doi: 10.4161/bioe.23574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Steidler L, Hans W, Schotte L, et al. Treatment of murine colitis by Lactococcus lactis secreting interleukin-10. Science. 2000;289:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhuang Z, Wu Z-G, Chen M, Wang PG. Secretion of human interferon-beta 1b by recombinant Lactococcus lactis. Biotechnol Lett. 2008;30:1819–1823. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9761-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pang Q, Ji Y, Li Y, et al. Intragastric administration with recombinant Lactococcus lactis producing heme oxygenase-1 prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxemia in rats. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;283:62–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.LeBlanc ADM, LeBlanc JG, Perdigón G, et al. Oral administration of a catalase-producing Lactococcus lactis can prevent a chemically induced colon cancer in mice. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:100–105. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47403-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.del Carmen S, de LeBlanc ADM, Levit R, et al. Anti-cancer effect of lactic acid bacteria expressing antioxidant enzymes or IL-10 in a colorectal cancer mouse model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;42:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kajikawa A, Masuda K, Katoh M, Igimi S. Adjuvant effects for oral immunization provided by recombinant Lactobacillus casei secreting biologically active murine interleukin-1β. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:43–48. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00337-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fredriksen L, Kleiveland CR, Hult LTO, et al. Surface display of N-terminally anchored invasin by Lactobacillus plantarum activates NF-κB in monocytes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:5864–5871. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01227-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang Z, Yu Q, Gao J, Yang Q. Mucosal and systemic immune responses induced by recombinant Lactobacillus spp. expressing the hemagglutinin of the avian influenza virus H5N1. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:174–179. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05618-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Benbouziane B, Ribelles P, Aubry C, et al. Development of a stress-inducible controlled expression (SICE) system in Lactococcus lactis for the production and delivery of therapeutic molecules at mucosal surfaces. J Biotechnol. 2013;168:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bermudez-Humaran LG, Cortes-Perez NG, Lefevre F, et al. A novel mucosal vaccine based on live lactococci expressing E7 antigen and IL-12 induces systemic and mucosal immune responses and protects mice against human papillomavirus type 16-induced tumors. J Immunol. 2005;175:7297–7302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li Y, Li X, Liu H, et al. Intranasal immunization with recombinant lactococci carrying human papillomavirus E7 protein and mouse interleukin-12 DNA induces E7-specific antitumor effects in C57BL/6 mice. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:576–582. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cortes-Perez NG, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Le Loir Y, et al. Mice immunization with live lactococci displaying a surface anchored HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;229:37–42. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00778-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rangel-Colmenero BR, Gomez-Gutierrez JG, Villatoro-Hernández J, et al. Enhancement of Ad-CRT/E7-mediated antitumor effect by preimmunization with L. lactis expressing HPV-16 E7. Viral Immunol. 2014;27:463–467. doi: 10.1089/vim.2014.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kitagawa K, Oda T, Saito H, et al. Development of oral cancer vaccine using recombinant Bifidobacterium displaying Wilms’ tumor 1 protein. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:787–798. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-1984-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kimura NT, Taniguchi SI, Aoki K, Baba T. Selective localization and growth of Bifidobacterium bifidum in mouse tumors following intravenous administration. Cancer Res. 1980;40:2061–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yazawa K, Fujimori M, Nakamura T, et al. Bifidobacterium longum as a delivery system for gene therapy of chemically induced rat mammary tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;69:256. doi: 10.1023/a:1010644217648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fujimori M, Amano J, Taniguchi S. The genus Bifidobacterium for cancer gene therapy. Curr Opin Drug Discov Dev. 2002;5:200–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sasaki T, Fujimori M, Hamaji Y, et al. Genetically engineered Bifidobacterium longum for tumor-targeting enzyme-prodrug therapy of autochthonous mammary tumors in rats. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:649–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fujimori M. Genetically engineered bifidobacterium as a drug delivery system for systemic therapy of metastatic breast cancer patients. Breast cancer. 2006;13:27–31. doi: 10.2325/jbcs.13.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wei C, Xun AY, Wei XX, et al. Bifidobacteria expressing tumstatin protein for antitumor therapy in tumor-bearing mice. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2015;15:498–508. doi: 10.1177/1533034615581977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fu G-F, Li X, Hou Y-Y, et al. Bifidobacterium longum as an oral delivery system of endostatin for gene therapy on solid liver cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005;12:133–140. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wang C, Ma Y, Hu Q, et al. Bifidobacterial recombinant thymidine kinase-ganciclovir gene therapy system induces FasL and TNFR2 mediated antitumor apoptosis in solid tumors. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:545. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2608-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cano-Garrido O, Seras-Franzoso J, Garcia-Fruitós E. Lactic acid bacteria: reviewing the potential of a promising delivery live vector for biomedical purposes. Microb Cell Fact. 2015;14:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Li W, Li C-B. Effect of oral Lactococcus lactis containing endostatin on 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon tumor in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7242–7247. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i46.7242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yi C, Huang Y, Guo Z, Wang S. Antitumor effect of cytosine deaminase/5-fluorocytosine suicide gene therapy system mediated by Bifidobacterium infantis on melanoma. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:629–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]