Abstract

Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) are increasingly reported worldwide being necessary the local epidemiological monitoring. Our aim was to characterize the hypermucoviscous CRKP isolates collected in our hospital during a 6 months period. Carriage of the carbapenemase genes (blaKPC, blaNDM, blaVIM and blaOXA-48), extended spectrum β-lactamases (blaSHV-2, blaCTX-M) and the virulence genes (magA, k2A, rmpA, wabG, uge, allS, entB, ycfM, kpn, wcaG, fimH, mrkD, iutA, iroN, hly and cnf-1) were determined by multiplex-PCR. Genetic relationship among the isolates was performed by PFGE and MLST. A total of 35 isolates were recovered, being the urinary and respiratory tract the most common infection sites (34.2%). The blaKPC-2 gene was present in all the isolates, coexisting with blaCTX-M-2 (45.7%), blaSHV-2 (28.6%), and blaCTX-M-2/blaSHV-2 (14.3%). The capsular serotype K2 corresponded with 68.6% of the isolates. Virulence factors frequency were variable [adhesins (97.1%), siderophores (94.3%) and phagocytosis resistance (wabG 48.5%, uge 80% and ycfM 57.1%)]. A total of 10 STs were identified although 40% of them clustered on ST25-CC65, and 17% to ST17. The incidence of KPC-2-producing K. pneumoniae reported by the hospital was 0.290 per 1000 admissions. In summary we described an epidemic scenario of multidrug resistant hypermucoviscous KPC-2 producing ST25 K. pneumoniae in our institution.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Infectious disease, Microbiology, Carbapenemase, KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Multi-clonal

1. Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a member of the ESKAPE group (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) and the Gram-negative leading bacterium in hospital acquired-infections (HAIs) [1, 2]. It was considered to be the most important causal agent of community-acquired infections; but in the early 1970s the epidemiology and infections spectrum dramatically changed when this bacterium was established in the hospital environment. This pathogen has developed increasing resistance to carbapenems, the last resort antibiotics typically used to treat multidrug resistant strains in hospital patients. Regretfully, now carbapenem resistant K. pneumoniae isolates are resistant to almost all available antibiotics and is associated with high rates of mortality [3].

The hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae isolates differ from classical mucosal strains because they present a positive string test. Since these K. pneumoniae variant were reported, hypermucoviscosity had been associated with hypervirulent strains; then new evidence has suggested that hypermucoviscosity and hypervirulence are two different phenotypes that should not be used synonymously regardless of whether they can act in synergy under certain circumstances [4].

Pathogenic K. pneumoniae strains have the potential to cause a wide variety of infectious diseases, including urinary tract, respiratory tract and blood infections [5]. Some virulent factors have been described codifying for capsule (magA, k2A, wcaG), hypermucoviscosity-associated gene A specific to K1 capsule serotype (magA, rpmA), adhesins (fimH, mrkD, kpn), lipopolysaccharides (wabG, uge, ycfM), iron acquisition systems (iutA, iroN, entB) and other virulence factors (allS, hly, cnf-1) that enable them to overcome host defenses, although it is not clear the linkage of these genes with antibiotic resistance [6].

Carbapenem hydrolysing β-lactamases have been reported to be increasingly widespread. Ambler molecular class A (KPC), class B (VIM, IMP, NDM) and class D (OXA-48) types are the most frequently found in K. pneumoniae causing serious nosocomial infections [7]. In South America, carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae was initially reported in 2006 in Colombia [8] and after in Brazil and Argentina [9, 10]. The hospital-acquired high-risk clones sequence types (ST) ST258 and ST11 were worldwide disseminated [11], whereas the Latin America local epidemiology pointed out to ST11 and ST437 associated to blaKPC-2 and blaKPC-3 production [12, 13]. In reference to our country, Argentina, previous studies demonstrated that the emergence of blaKPC-2 is also associated with CC258 [14].

The aim of this study was to determine the clinical, epidemiological and molecular patterns of hypermucoviscous carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates causing nosocomial infections at a tertiary referral hospital in Tucumán, Argentina.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

This retrospective study was conducted in a teaching hospital in Tucumán, Argentina (500 beds) with approximately 3000 admissions/day. Over a period of 6 months, from May 1 to October 31, 2014, all patients suffering from K. pneumoniae infections, resistant to carbapenemes and hospitalized for more than 48 hours were studied; patients from other hospitals or with community-acquired infections or without strict infection criteria were not included in this study. After the patients signed an informed consent, the clinical history was accessed and the clinical-epidemiological information was registered: name and surname, age, sex, time of hospitalization prior to isolation, hospital stay, comorbidities, probable site of the acquisition of the infection, type of infection and antibiotic treatment used. Institutional activity data (number of admissions and mean length of stay) of this period were collected by the hospital for the calculation of incidence rates. The ethics committee of the Ángel C. Padilla hospital approved the study and authorized the access to clinical information.

2.2. Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Bacterial identification was confirmed by MALDI-TOF (matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight) (Microflex LT, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany), susceptibility patterns were determined by the automated Vitex 2® system (BioMerieux, Merci l'Etoile, France) and????? by broth microdilution method including ampicillin (AMP), ampicillin/sulbactam (SAM), piperacillin/tazobactam (PTAZ), cephalothin (CEF), cefotaxime (CTX), ceftazidime (CAZ), cefepime (FEP), meropenem (MER), imipenem (IMP), gentamicin (GEN), amikacin (AKN), colistin (COL), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMS) and ciprofloxacin (CIP). Breakpoints were defined following the document M100-S24 of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [15]. Susceptibility to tigecycline was determined by broth microdilution method and for fosfomycin by agar dilution method with glucose-6-phosphate (25 mg/L in the medium). Breakpoints were defined according to the Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [16]. Synergy tests with boronic acid and EDTA disks close to the carbapenemes and the modified Hodge test (MHT) were performed for the detection of carbapenemases [17]. K. pneumoniae ATCC700603 and Eschercihia coli ATCC 25922 were used as quality control strains for the antibiotic susceptibility tests.

2.3. Detection of the hypermucoviscous phenotype

All carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates were grown in nutritive agar (Britania®) enriched with 5% defibrinated blood, Mac Conkey agar (Britania®) and CLED agar (Britania®). Hypermucoviscosity phenotype was defined by the formation of a viscous filament ≥5 mm after stretching a colony with a loop on all the agar plates tested [18, 19].

2.4. Strain selection

All the hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae strains were selected on the basis of MIC values of ≥2 mg/liter for any of the carbapenems imipenem, meropenem or ertapenem and synergy and Hodge tests positive.

2.5. β-lactamases molecular characterization

DNA extracts were prepared by boiling the bacterial suspensions [20]. Multiplex PCR targeting carbapenemase genes (blaKPC, blaNDM, blaVIM and blaOXA-48) and extended spectrum β-lactamases-ESBLs: SHV variants including SHV-2 (blaSHV-2) and CTX-M variants including CTX-M-2 (blaCTX-M-2) were performed [21]. The amplicons were sequenced with ABI3130CL (Applied Biosystems, USA) and the sequences were analyzed on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [22]. The complete CDS of the β-lactamases detected has not been determined and the indicated allelic variant has been obtained from partial sequences.

2.6. Analysis of virulence gene regions

The virulence genes were detected in four-separated multiplex PCR reactions (magA-fimH-uge-iutA, wabG-rmpA-cnf1-ycfM, hly-iroN-k2A-mrkD, and kpn-allS-entB-wcaG) with the following thermal cycling conditions: 5 minutes of pre-denaturation at 95 °C, followed by 30 cycles: 1 minute at 94 °C, 1 minute at 58 °C, 1 minute at 72 °C and 10 minutes of final elongation at 72 °C (Sensoquest Labcycler, Germany) [6].

2.7. Population structure

Molecular typing was performed by pulsed-field electrophoresis (PFGE) and Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST). Isolates were typed by PFGE of SpeI-digested total genomic DNA (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan), and the DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on 1 % SeaKeam Gold agarose (Lonza, Rockland, ME, United States) in 0.5X TBE (45 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid, 1.0 mM EDTA; ph 8.0) buffer using the CHEF Mapper XA PFGE system (Bio-Rad, United States) at 6 V/cm2 and 14 °C, with alternating pulses at a 120° angle in a 5–20 s pulse time gradient for 19 h. DNA patterns were interpreted according to Tenover et al [23]. Strains were considered to be the same clone (type) if they showed ≥75% genetic identity, or fewer than three fragment differences on the PFGE profiles. Subsequently one isolate for each PFGE pulsotype was submitted to MLST technique following the K. pneumoniae MLST website guidelines [24].

3. Results

A total of 35 patients, which their clinical-epidemiological characteristics are shown on Table 1, infected by carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae were identified. Patients were admitted in a range of 3–74 days previous to the carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae detection. The sample sources were the respiratory tract (n = 12, 34.2%), urinary tract (n = 12, 34.2%), soft tissue (n = 5, 14.2%), blood (n = 2, 5.7%), cerebrospinal fluid (n = 2, 5.7%) bone (n = 1, 2.8%), and abdominal fluid (n = 1, 2.8%).

Table 1.

Clinical-epidemiological characteristics of 35 patients included in the study.

| Population Characteristics | Patients number (%) |

|---|---|

| Male sex | 22 (62.8%) |

| Comorbilities | |

| Diabetes | 6 (17.1%) |

| Neoplasia | 4 (11.4%) |

| Cronic renal insuffiency | 3 (8.5%) |

| Reumathoid disease | 2 (5.7%) |

| No Comorbilities | 20 (57.1%) |

| Site of adquisition | |

| Intensive care unit | 16 (45.7%) |

| Room 3 | 6 (17.1%) |

| Surgery | 6 (17.1%) |

| Room 10 | 1 (2.9%) |

| Room11 | 2 (5.7%) |

| Intermediate care unit | 2 (5.7%) |

| Room 8 | 1 (2.9%) |

| Room 7 | 1 (2.9%) |

| Type of infection | |

| Urinary tract infection | 11 (31.4%) |

| Surgery wound infection | 5 (14.2%) |

| Respiratory tract infection | 10 (28.5%) |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 5 (14.2%) |

| catheter-related infections | 1 (2.8%) |

| Osteoarticular infections | 2 (5.7%) |

| Bacteremia | 1 (2.8%) |

| Antibiotics useda | |

| Amikacin | 27 (77.1) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4 (11.4) |

| Colistin | 25 (71.4) |

| Imipenem | 14 (40.0) |

| Meropenem | 11 (31.2) |

| piperacillin/tazobactam | 29 (82.8) |

| Vancomycin | 2 (5.71) |

All antibiotics mentioned were combined in different therapeutic schemes.

All 35 isolates were multidrug resistant, have similar susceptibility profiles (Table 2), and carried the blaKPC-2 gene. In 16 isolates (45.7%) the blaCTX-M-2 gene was also amplified, as well as blaSHV-2 in 10 isolates (28.6%) and blaCTX-M-2/blaSHV-2 in 5 isolates (14.3%). Virulence factors carriage were as follows: adhesins (97.1%), siderophores (94.3%) and phagocytosis resistance (74.3%) (Table 3). The capsular serotype K2 was identified in 68.6% of the isolates, and in the remaining isolates the tipification was not possible.

Table 2.

Susceptibility testing and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) results of 35 CRKP isolates.

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC range | MIC50 (mg/L) | MIC90 (mg/L) | Number of S (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | 0 (0) |

| Ampicillin/Sulbactam | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | 0 (0) |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam | 16-≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | 0 (0) |

| Cefalotin | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 0 (0) |

| Cefotaxime | ≤1-≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 3 (1) |

| Ceftazidime | 4-≥64 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 11 (31) |

| Cefepime | ≤1-≥64 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 24 (68) |

| Meropenem | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 0 (0) |

| Imipenem | 8-≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 0 (0) |

| Gentamicin | ≤1-≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 8 (22) |

| Amikacin | ≤2-16 | ≤2 | ≤2 | 35 (100) |

| Colistin | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 35 (100) |

| Tigecyclinea | 0.25–1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 33 (94) |

| Fosfomycin intravenous | <32-64 | <32 | <32 | 34 (97) |

| Trimethoprim/Sulfametoxazole | ≤20-≥320 | ≥320 | ≥320 | 11 (31) |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25–32 | 1 | 1 | 0 (0) |

S Susceptible strains.

Interpreted according to EUCAST clinical breakpoints for E. coli.

Table 3.

Carbapenem resistance and virulence gene profiles of K. pneumoniae strains.

| ST/Capsular Type | Strain | Clinical sources | Carbapenemase, ESBLa | Virulence gene profiles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST25/K2 | 1 | Bone | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | uge,wabG,ycfM,iroN,mrkD,kpn,entB |

| 3 | Purulent | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | uge,iroN,mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| 4 | Urine | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | uge,ycfM,iroN,mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| 6 | Urine | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | uge,wabG,ycfM,iroN,mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| 7 | LCR | KPC-2 | uge,mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| 9 | Purulent | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | uge,wabG,ycfM,iroN,kpn,entB | |

| 10 | Purulent | KPC-2 | uge,wabG,iroN,kpn,entB | |

| 21 | Bal | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | uge,ycfM,mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| 26 | Urine | KPC-2, CTX-M-2, SHV-2 | mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| 27 | Bal | KPC-2, CTX-M-2, SHV-2 | ycfM,mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| 28 | Urine | KPC-2, CTX-M-2, SHV-2 | ycfM,mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| 35 | Bal | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | uge,wabG,ycfM,iroN,mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| 36 | Bal | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | uge,wabG,ycfM,iroN,kpn,entB | |

| S25/NT | 17 | Abdominal | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | ycfM,kpn,entB |

| ST17/K2 | 8 | Bal | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | uge,ycfM,iroN,mrkD,kpn,entB |

| ST17/NT | 15 | Urine | KPC-2, SHV-2 | uge,wabG,ycfM,kpn,entB |

| 23 | Bal | KPC-2, SHV-2 | kpn | |

| 24 | Urine | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | kpn,etnB | |

| 25 | Blood | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| ST629/K2 | 16 | Bal | KPC-2 | wabG,ycfM,mrkD,kpn,entB |

| 30 | Bal | KPC-2, SHV-2 | uge,wabG,ycfM,iroN,mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| 34 | Bal | KPC-2 | ycfM,kpn,entB | |

| ST629/NT | 38 | Purulent | KPC-2, SHV-2 | uge,kpn,entB |

| ST995/K2 | 11 | Urine | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | uge,mrkD,kpn,entB |

| ST147/NT | 12 | LCR | KPC-2, SHV-2 | uge,kpn,entB |

| 37 | Bal | KPC-2, SHV-2 | uge,mrkD,kpn,entB | |

| ST258/K2 | 20 | Urine | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | mrkD,kpn,entB |

| ST268/K2 | 14 | Urine | KPC-2, CTX-M-2, SHV-2 | uge,mrkD,kpn,entB |

| ST133/K2 | 39 | Bal | KPC-2, SHV-2 | mrkD,kpn,entB |

| ST111/NT | 40 | Blood | KPC-2, CTX-M-2, SHV-2 | uge,kpn,entB |

| ST551/NT | 41 | Bal | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | entB |

| Clon A/K2 | 13 | Urine | KPC-2, SHV-2 | kpn,etnB |

| Clon B/K2 | 22 | Urine | KPC-2, SHV-2 | uge,iutA,ycfM,mrkD |

| Clon C/NT | 32 | Urine | KPC-2, CTX-M-2 | uge,wabG,iroN,kpn,entB |

| Clon D/K2 | 33 | Purulent | KPC-2, SHV-2 | uge,wabG,ycfM,iroN,mrkD,kpn,entB |

References: genes associated with the resistance to phagocytosis (uge, ycfM, wabG), adhesins (mrkD, kpn), capsular elements (magA, k2A), iron adquisition systems (entB, iroN), associated with the celular wall (WabG), and others virulence factors (allS). K2: capsular antigen 2. NT: non-typable. Bal: bronchoalveolar lavage. LCR: cerebrospinal fluid. ESBL: extended spectrum β-lactamases.

The complete CDS of the β-lactamases detected has not been determined and the indicated allelic variant has been obtained from partial sequences.

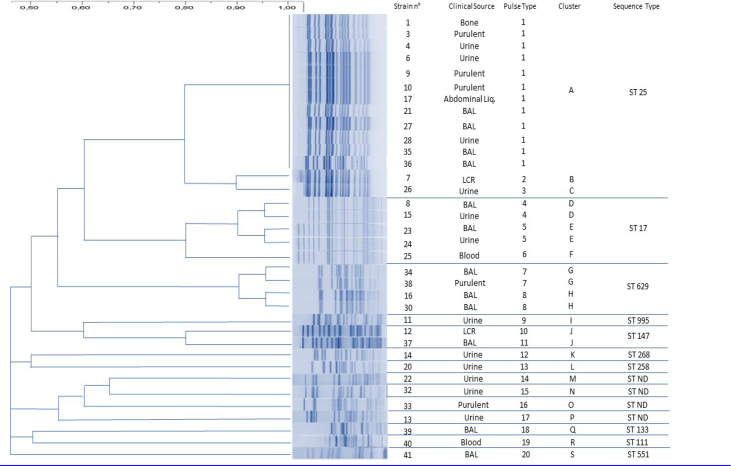

We identified a total of 20 PFGE pulsotypes (PT) grouped into different clusters (A-S), corresponding to 10 STs, ST25 was the most represented clone, followed by ST629, ST17, ST147, ST268, ST258, ST11, ST111, ST133, ST551 and 4 isolates with allelic combinations not previously documented (Table 3, Fig. 1). The overall incidence of KPC-2 K. pneumoniae reported by the hospital was 0.290 per 1000 admissions.

Fig. 1.

DNA finger printing by PFGE and relation to ST type in KPC-2 Klebsiella pneumoniae strains.

4. Discussion

The rapid spread of KPC-producing K. pneumoniae is a major clinical and public health concern and continue epidemiological surveillance is necessary. These broad-spectrum β-lactamases are increasing in new locations worldwide, indicating an ongoing process [25, 26]. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) reports that Argentina is one of the countries with the most “pandrug resistant" nosocomial isolations of Latin America [27]. Besides the numerous efforts made at local or national level to control the spread of these species, the rapid dissemination of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae constituted a clinically relevant problem of our region. Tucuman is situated, in the north of Argentine (NOA), within a multi border area limiting with Bolivia, Chile and Paraguay. Since 2006 an active monitoring for carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae detection is carried out in our Department.

The present study is focused on the molecular characterization of carbapenem-resistant hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae. The incidence rate of these strains in our institution was 0.290 per 1000 admissions, higher than the rate registered in Belgium where the average incidence among 9 hospitals was 0.223 per 1000 admissions [28] and even greater than in Germany where it is significantly lower (0.047 per 1000 admissions) [29]. The average time of hospitalization prior to the acquisition of the infection was 30 days, denoting the high hospital stay; the Intensive Care Unit was the most common site of acquisition, in line with previous reports [26, 30, 31, 32, 33]. Unlike other studies, the urinary and respiratory tract was the most common sources of clinical samples (34.2%), followed by soft tissue (14.2%) and blood (5.7%), while other authors reported bacteremia as the leading site of infection [34, 35].

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing confirmed resistance to piperacillin/tazobactam, ciprofloxacin and meropenem in all isolates, higher than the results found in Belgian hospitals: 43.9%, 80.3% and 53% respectively. The resistance proportion for tigecycline and colistin was still lower with only 2 and 1 strain respectively [28].

Focusing on the molecular and genetic characterization, we found Extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) genes as blaCTX-M-2 (45.7%), blaSHV-2 (28.6%) and blaCTX-M-2/blaSHV-2 (14.3%). These results differ from that described by Canton et al. reporting of blaCTX-M-9 in 96% of the isolates, whereas only 1% contained the blaCTXM-15 gene, which is by far the most prevalent CTX-M variant worldwide [36].

KPC-2 is the most prevalent carbapenemase in China, with rare detection of metallo-carbapenemases, the same as other Latin American countries that present blaKPC-2 and blaKPC-3 in agreement with our results. However, some other countries may have another dominant carbapenemases; for example, the United Kingdom is likely to have a mixed carbapenemase pattern with VIM and NDM, and NDM types followed by OXA-48-like types were prevalent in India [37, 38].

Molecular typing of our strains showed a clonal dissemination of ST25 and ST17, whereas other Latin America studies reported ST11 and ST437 associated with the spread of blaKPC-2 and blaKPC-3 [9, 39, 40]. Previous studies located in Argentina described ST258 as the dominant clonal type [14]. The importance of ST25-CC65 was previously described by Brisse et al. [41].

Since the presence of hypermucoviscous variants of K. pneumoniae in the world, many cases of invasive infections caused by these pathogens were described. Nevertheless, today the terms hypermucoviscous and hypervirulent are different and genes associated with the virulence must be determined [4]. Although in hypervirulent strains the K1 and K2 capsular types were the most exhaustively described, it has been demonstrated that K. pneumoniae producing infection and non-hypervirulent strains can also showed the K2 serotype [42]. Our isolates showed a K2 serotype associated with different genetic lineages in coincidence with Zhao et al. that also demonstrated the K2 serotype in 68.7% of the hypermucoviscosity-positive K. pneumoniae isolates [43].

Isolates containing the magA, cnf-1, hly and allS genes were not detected in coincidence with Aksöz et al. In this study, capsule associated genes were wabG (48.5%), uge (80%), and ycfM (57.1%), encoding capsule, lipoprotein, and external membrane protein, respectively. These results are consistent with previous studies reporting wabG (in 88% of isolates), uge (86%), ycfM (80%) and entB (72%) [6]. According to the distribution of virulence genes 16 virulence profiles/35 CRKP strains were defined according with Aksöz et al., who described 29 virulence profiles/34 CRKP strains. This situation evidences the high possibilities of virulence factors combination, forcing the molecular typing at individual isolates level.

The studied strains express two types of fimbrial adhesins; type 1 and type 3 fimbriae [5]. While type 1 fimbriae, encoding fimH, play an important role in urinary tract infections caused by these strains, type 3 fimbriae, encoding mrkD, promote biofilm development [44]. Besides it, siderophores encoding entB, iutA and iroN, are iron binding proteins and they also promote biofilm formation [45,46]. In this study, total fimbrial adhesins (fimH, mrkD and kpn) were observed in 34 isolates (97.1%) and siderophores (entB and iroN) in 33 isolates (94.2%) similar as were observed by other authors that described total fimbrial adhesins in 42 strains (84%) and siderophores (entB and iroN) in 40 isolates (80%). This situation shows that these virulence factors are important for Klebsiella pathogenicity. It is interesting to note that two strains, 23 and 41, have a single virulence factor: kpn and entB, respectively.

In summary, we reported an epidemic scenario of hypermucoviscous blaKPC-2 producing ST25 and ST17 K. pneumoniae from a single hospital in Tucuman, Argentina. This study reinforces the needed of continues surveillance to prevent a major dissemination of ST25-CC65.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Juan Martín Vargas: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper

María Paula Moreno Mochi: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data

Juan Manuel Nuñez, Mariel Cáceres, Silvana Mochi: Performed the experiments

Rosa del Campo Moreno: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper

María Angela Jure: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper

Funding statement

This work was supported by a project obtained through a contest, granted by SCAIT (Secretaría de Ciencia, Arte e Innovación Tecnológica).

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Holt K.E., Wertheim H., Zadoks R.N., Baker S., Whitehouse C.A., Dance D., Jenney A., Connor T.R., Hsu L.Y., Severin J., Brisse S., Cao H., Wilksch J., Gorrie C., Schultz M.B., Edwards D.J., Nguyen K.V., Nguyen T.V., Dao T.T., Mensink M., Minh V.L., Nhu N.T., Schultsz C., Kuntaman K., Newton P.N., Moore C.E., Strugnell R.A., Thomson N.R. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 2015;112(27):E3574–E3581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501049112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boucher H.W., Talbot G.H., Bradley J.S., Edwards J.E., Gilbert D., Rice L.B., Scheld M., Spellberg B., Bartlett J. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! an update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48(1):1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzouvelekis L.S., Markogiannakis A., Psichogiou M., Tassios P.T., Daikos G.L. Carbapenemases in Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae: an evolving crisis of global dimensions. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012;25(4):682–707. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05035-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catalán-Nájera J.C., Garza-Ramos U., Barrios- Camacho H. 2017. Hypervirulence and Hypermucoviscosity: Two Different but Complementary Klebsiella Spp. Phenotypes? ISSN: 2150-5594 2150-5608 (Online) Journal Homepage.http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/kvir20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Podschun R., Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998;11(4):589–603. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Candan E.D., Aksöz N. Klebsiella pneumoniae: characteristics of carbapenem resistance and virulence factors. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2015;62(4):867–874. doi: 10.18388/abp.2015_1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordmann P., Naas T., Poirel L. Global spread of carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17(10):1791–1798. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villegas M.V., Lolans K., Correa A., Suarez C.J., Lopez J.A., Vallejo M. Colombian Nosocomial Resistance Study Group. First detection of the plasmid-mediated class A carbapenemase KPC-2 in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from South America. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2880–2882. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00186-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monteiro J., Fernandes Santos A., Asensi M.D., Peirano G., Gales A.C. First report of KPC-2–producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in Brazil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:333–334. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00736-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasteran F.G., Otaegui L., Guerriero L., Radice G., Maggiora R., Rapoport M., Faccone D., Di Martino A., Galas M. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-2, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008;14:1178–1180. doi: 10.3201/eid1407.070826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitchel B., Rasheed J.K., Patel J., Srinivasan A., Venezia S., Carmeli Y., Brolund A., Giske C. Molecular epidemiology of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in the United States: clonal expansion of Multilocus sequence type 258. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53(8):3365–3370. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00126-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrade L.N., Curiao T., Ferreira J.C., Longo M.J., Clímaco E.C., Carneiro E., Martinez R Baquero F., Canton R., Coque T. Dissemination of blaKPC-2 by the spread of Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal complex 258 clones (ST258, ST11, ST437) and plasmids (IncFII, IncN, IncL/M) among Enterobacteriaceae species in Brazil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3579–3583. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01783-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castanheira M., Costello J.A., Deshpande L.M., Jones R.N. Expansion of clonal complex 258 KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Latin American hospitals: report of the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1668–1669. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05942-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez S.A., Pasteran F.G., Faccone D., Tijet N., Rapoport M., Lucero C., Lastovetska O., Albornoz E., Galas M., KPC Group. Melano R.G., Corso A., Petroni A. Clonal dissemination of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 harbouring KPC-2 in in Argentina. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) CLSI; Wayne: 2014. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twenty-Four Informational Supplement. CLSI Document M100-24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) European Commite on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST); 2014. Clinical Breakpoints Version 4.0.http://www.eucast.org [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasteran F., Mendez T., Guerriero L., Rapoport M., Corso A. Sensitive screening tests for suspected class A carbapenemase production in species of Enterobacteriaceae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47(6):1631–1639. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00130-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H.C., Chuang Y.C., Yu W.L., Lee N.Y., Chang C.M., Ko N.Y. Clinical implications of hypermucoviscosity phenotype in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates: association with invasive syndrome in patients with community-acquired bacteraemia. J. Intern. Med. 2006;259:606–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang C., Chuang Y., Shun C., Chang S., Wang J. A novel virulence gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing primary liver abscess and septic metastatic complications. J. Exp. Med. 2004 doi: 10.1084/jem.20030857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark N.C., Cooksey R.C., Hill B.C., Swenson J.M., Tenover F.C. Characterization of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993;37(11):2311–2317. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dallenne C.1, Da Costa A., Decré D., Favier C., Arlet G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010 Mar;65(3):490–495. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

- 23.Tenover F.C., Arbeit R.D., Goering R.V., Mickelsen P.A., Murray B.E., Persing D.H., Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995;33(9):2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klebsiella pneumoniae BIGSdb - Institut Pasteur. http://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/.

- 25.Girmenia C., Serrao A., Canichella M. Epidemiology of carbapenem resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in mediterranean countries. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2016;8(1) doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2016.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee C.-R., Lee J.H., Park K.S., Kim Y.B., Jeong B.C., Lee S.H. Global dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: epidemiology, genetic context, treatment options, and detection methods. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:895. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antimicrobial Surveillance Program SENTRY. World Health Organization; 2014. www.who.int [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Laveleye M., Huang T.D., Bogaerts P., Berhin C., Bauraing C., Sacré P. Increasing incidence of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Belgian hospitals. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017;36:139–146. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaase M., Schimanski S., Schiller R., Beyreiß B., Thürmer A., Steinmann J., Kempf V.A., Hess C., Sobottka I., Fenner I., Ziesing S., Burckhardt I., von Müller L., Hamprecht A., Tammer I., Wantia N., Becker K., Holzmann T., Furitsch M., Volmer G., Gatermann S.G. Multicentre investigation of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in German hospitals. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Córdova E., Lespada M.I., Gómez N., Pasterán F., Oviedo V., Rodríguez-Ismael C. Clinical and epidemiological study of an outbreak of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clínica. 2012;30(7):376–379. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gasink L.B., Edelstein P.H., Lautenbach E., Synnestvedt M., Fishman N.O. Risk factors and clinical impact of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumonia. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2009:1180–1185. doi: 10.1086/648451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lucena A., Dalla Costa L.M., Nogueira K.S., Matos A.P., Gales A.C., Paganini M.C., Castro M.E., Raboni S.M. Nosocomial infections with metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa: molecular epidemiology, risk factors, clinical features and outcomes. J. Hosp. Infect. 2014;87(4):234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoxha A., Karki T., Giambi C., Montano C., Sisto A., Bella A. Attributable mortality of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in a prospective matched cohort study in Italy, 2012-2013. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016;92:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng B., Dai Y., Liu Y., Shi W., Dai E., Han Y., Zheng D., Yu Y., Li M. Molecular epidemiology and risk factors of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in eastern China. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1061. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Falagas M.E., Bliziotis I.A., Michalopoulos A., Sermaides G., Papaioannou V.E., Nikita D., Choulis N. Effect of a policy for restriction of selected classes of antibiotics on antimicrobial drug cost and resistance. J. Chemother. 2007;19(2):178–184. doi: 10.1179/joc.2007.19.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cantón R., González-Alba J.M., Galán J.C. CTX-M Enzymes: Origin and diffusion. Front. Microbiol. 2012;2(3):110. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munoz-Price L.S., Poirel L., Bonomo R.A., Schwaber M.J., Daikos G.L., Cormican M., Cornaglia G., Garau J., Gniadkowski M., Hayden M.K., Kumarasamy K., Livermore D.M., Maya J.J., Nordmann P., Patel J.B., Paterson D.L., Pitout J., Villegas M.V., Wang H., Woodford N., Quinn J.P. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13(9):785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ranjbar R., Memariani H., Sorouri R., Memariani M. Distribution of virulence genes and genotyping of CTX-M-15-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from patients with community-acquired urinary tract infection (CA-UTI) Microb. Pathog. 2016;100:244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrade L.N., Curiao T., Ferreira J.C., Longo M.J., Clímaco E.C., Carneiro E., Martinez R., Baquero F., Canton R., Coque T. Dissemination of blaKPC-2 by the spread of Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal complex 258 clones (ST258, ST11, ST437) and plasmids (IncFII, IncN, IncL/M) among Enterobacteriaceae species in Brazil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3579–3583. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01783-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castanheira M., Costello J.A., Deshpande L.M., Jones R.N. Expansion of clonal complex 258 KPC-2-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Latin American hospitals: report of the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;56:1668–1669. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05942-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brisse S., Fevre C., Passet V., Issenhuth-Jeanjean S., Tournebize R., Diancourt L. Virulent clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae: identification and evolutionary scenario based on genomic and phenotypic characterization. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee C.R., Lee J.H., Park K.S., Jeon J.H., Kim Y.B., Cha C.J., Jeong B.C., Lee S.H. Antimicrobial resistance of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: epidemiology, hypervirulence-associated determinants, and resistance mechanisms. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017;21(7):483. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao J., Chen J., Zhao M., Qiu X., Chen X., Zhang W., Sun R., Ogutu J.O., Zhang F. Multilocus sequence types and virulence determinants of hypermucoviscosity-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from community-acquired infection cases in Harbin, north China. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;69(5):357–360. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2015.321. 21;Epub 2016 Jan 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Struve C., Bojer M., Krogfelt K.A. Identification of a conserved chromosomal region encoding Klebsiella pneumoniae type 1 and type 3 fimbriae and assessment of the role of fimbriae in pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 2009;77(11):5016–5024. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00585-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.May T., Okabe S. Enterobactin is required for biofilm development in reduced-genome Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;13:3149–3162. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.El Fertas-Aissani R., Messai Y., Alouache S., Bakour R. Virulence profiles and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from different clinical specimens. Pathol. Biol. 2013;61:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]