Key Points

Question

What factors are associated with receipt of eye care among US adults?

Findings

Results of this cross-sectional online survey study showed that more than 80% of US adults aged 50 to 80 years reported undergoing an eye examination in the past 2 years. Respondents who were unmarried, had lower incomes, or resided outside the northeast were less likely to report recent eye care; common reasons for not undergoing an eye examination included not having an eye problem, cost, and lack of insurance coverage.

Meaning

Overall, eye care use among US adults appears to be high; however, there are socioeconomic and demographic differences that might be addressed through targeted policy interventions.

Abstract

Importance

Contemporary data on use of eye care by US adults are critical, as the prevalence of age-related eye disease and vision impairment are projected to increase in the coming decades.

Objectives

To provide nationally representative estimates on self-reported use of eye care by adults aged 50 to 80 years, and to describe the reasons that adults do and do not seek eye care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The National Poll on Healthy Aging, a cross-sectional, nationally representative online survey was conducted from March 9 to 24, 2018, among 2013 individuals aged 50 to 80 years.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The proportion of US adults who received an eye examination within the past 2 years as well as the sociodemographic and economic factors associated with receipt of eye care.

Results

Among 2013 adults aged 50 to 80 years (survey-weighted proportion of women, 52.5%; white non-Hispanic, 71.1%; mean [SD] age, 62.1 [9.0] years), the proportion reporting that they underwent an eye examination in the past year was 58.5% (95% CI, 56.1%-60.8%) and in the past 2 years was 82.4% (95% CI, 80.4%-84.2%). Among those with diabetes, 72.2% (95% CI, 67.2%-76.8%) reported undergoing an eye examination in the past year and 91.3% (95% CI, 87.7%-93.9%) in the past 2 years. The odds of having undergone an eye examination within the past 2 years were higher among women (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 2.00; 95% CI, 1.50-2.67), respondents with household incomes of $30 000 or more (AOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.08-2.29), and those with a diagnosed age-related eye disease (AOR, 3.67; 95% CI, 2.37-5.69) or diabetes (AOR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.50-3.54). The odds were lower for respondents who were unmarried (AOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.53-0.96), from the Midwest (AOR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.34-0.87) or West (AOR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.38-0.94), or reported fair or poor vision (AOR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.28-0.65). Reasons reported for not undergoing a recent eye examination included having no perceived problems with their eyes or vision (41.5%), cost (24.9%), or lack of insurance coverage (23.4%).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, the rate of eye examinations was generally high among US adults aged 50 to 80 years, yet there were several significant demographic and socioeconomic differences in the use of eye care. These findings may be relevant to health policy efforts to address disparities in eye care and to promote care for those most at risk for vision problems.

This cross-sectional online survey study provides nationally representative estimates on self-reported use of eye care by US adults aged 50 to 80 years and describes the reasons that adults do and do not seek eye care.

Introduction

Vision impairment and blindness affect 9% of US adults 65 years or older, and the annual economic burden of vision problems for this population is $77 billion.1 Poor vision is associated with an increased risk of falls, cognitive decline, and decreased independence.2 The prevalence of many common eye conditions increases with age, and poor and minority populations are disproportionately affected.2 However, most vision impairment is preventable or treatable with timely diagnosis and care.

In a 2016 report on eye health in the United States, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine identified the examination of disparities in access to eye and vision care for medically underserved populations as a key research need.2 Most recently published studies on national patterns of the use of eye care relied on data that were collected before the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was completed in 2014.3,4,5,6,7 Accordingly, the objective of this study was to provide contemporary national estimates on self-reported use of eye care and disparities in the use of eye care for US adults aged 50 to 80 years, and to describe the reasons that adults do not seek eye care.

Methods

Sample

The National Poll on Healthy Aging is a recurring survey of adults aged 50 to 80 years designed to inform the public, health care professionals, and policy makers on issues related to health.8 The National Poll on Healthy Aging vision survey was deployed in March 2018 by GfK Custom Research for the University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation.9 The survey was administered online to a randomly selected, stratified sample of 2013 individuals from GfK’s KnowledgePanel, which resembles the US population.10 The sample was weighted to reflect data from the US Census Bureau. Respondents were provided with a computer and internet access if needed to complete the survey. The Callegaro-DiSogra algorithms11 were used to calculate the survey response rate, and any differential nonresponse was accounted for in adjustment of the survey design weights. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board reviewed this study and deemed it exempt from human subjects review because it was a study of deidentified respondents.

Eye Care Questions

Respondents were asked when they last had their eyes examined by an “eye doctor” (ophthalmologist or optometrist). Responses were dichotomized into those who had received recent eye care (within 2 years) and those who had not. Self-reported near and distance vision was rated on a 5-point scale (where 1 indicated excellent and 5 indicated poor). Participants were also asked if they had received a diagnosis of an age-related eye disease, defined as cataracts, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, or diabetic eye disease. Respondents who had not undergone a recent eye examination were asked to report the reason(s) they had not received care. Those who reported receiving recent eye care were asked to select the main reason for seeking care. The complete vision survey is available in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Statistical Analysis

The weighted proportion of respondents for each covariate, stratified by receipt of recent eye care, was calculated and χ2 tests were performed. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate the odds of recent eye care; this model contained covariates predictive of recent eye care with P < .10 from χ2 tests, as well as race/ethnicity, a conceptually important factor.3,4,5,6 Self-rated distance vision was included but near vision was not because they were highly correlated. Analyses were conducted using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp) and accounted for the complex survey design.12 All P values were from 2-tailed tests and results were deemed statistically significant at P ≤ .05

Results

Respondent characteristics are presented in Table 1 stratified by receipt of eye care. Overall, 58.5% of respondents (95% CI, 56.1%-60.8%) reported having undergone an eye examination in the past year and 82.4% (95% CI, 80.4%-84.2%) in the past 2 years. Among those with diabetes, 72.2% (95% CI, 67.2%-76.8%) reported undergoing an eye examination in the past year and 91.3% (95% CI, 87.7%-93.9%) in the past 2 years. In a multivariable model (Table 2), those who reported recent eye care were significantly more likely to be female (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 2.00; 95% CI, 1.50-2.67), married or partnered, have a household income of $30 000 or more (AOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.08-2.29), live in the northeast United States, have diabetes (AOR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.50-3.54) or an age-related eye disease (AOR, 3.67; 95% CI, 2.37-5.69), and have better self-reported vision. The odds were lower for respondents who were unmarried (AOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.53-0.96), from the midwestern (AOR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.34-0.87) or western United States (AOR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.38-0.94), or had self-reported fair or poor vision (AOR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.28-0.65). The adjusted odds of receiving recent eye care were not significantly associated with age, race/ethnicity, or employment status.

Table 1. Weighted Sample Characteristics by Report of Recent Eye Examination Among US Older Adults.

| Characteristic | Respondents, % (95% CI) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eye Examination Within the Past 2 y (n = 1692) | Eye Examination >2 y in the Past or Not Sure (n = 315) | ||

| Total (n = 2007)b | 82.4 (80.4-84.2) | 17.6 (15.8-19.6) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 77.8 (74.7-80.6) | 22.2 (19.4-25.3) | <.001 |

| Female | 86.6 (84.0-88.8) | 13.4 (11.2-16.0) | |

| Age, y | |||

| 50-64 | 79.6 (76.8-82.2) | 20.4 (17.8-23.2) | <.001 |

| 65-80 | 87.0 (84.4-89.3) | 13.0 (10.7-15.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black non-Hispanic | 84.8 (77.9-89.8) | 15.2 (10.2-22.1) | .77 |

| Hispanic | 81.8 (74.7-87.2) | 18.2 (12.8-25.3) | |

| White non-Hispanic | 82.4 (80.2-84.5) | 17.6 (15.5-19.8) | |

| Other | 79.3 (68.0-87.4) | 20.7 (12.6-32.0) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 80.9 (78.0-83.5) | 19.1 (16.5-22.0) | .003 |

| Retired | 86.4 (83.5-88.9) | 13.6 (11.1-16.5) | |

| Not working at this time | 76.3 (69.1-82.4) | 23.7 (17.6-30.9) | |

| Annual household income, $ | |||

| <30 000 | 76.1 (70.7-80.7) | 23.9 (19.3-29.3) | .001 |

| 30 000-59 999 | 81.6 (77.4-85.1) | 18.4 (14.9-22.6) | |

| ≥60 000 | 85.2 (82.7-87.4) | 14.8 (12.6-17.3) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married or partnered | 84.5 (82.2-86.5) | 15.5 (13.5-17.8) | .002 |

| Not married or partnered | 78.1 (74.2-81.6) | 21.9 (18.4-25.8) | |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 87.0 (82.8-90.4) | 13.0 (9.6-17.2) | .06 |

| Midwest | 80.0 (75.5-83.9) | 20.0 (16.1-24.5) | |

| South | 83.2 (79.9-86.0) | 16.8 (14.0-20.1) | |

| West | 79.7 (75.0-83.7) | 20.3 (16.3-25.0) | |

| Self-rated distance vision | |||

| Excellent | 84.9 (81.1-88.0) | 15.1 (12.0-18.9) | <.001 |

| Very good | 85.9 (82.9-88.5) | 14.1 (11.5-17.1) | |

| Good | 78.5 (73.9-82.4) | 21.5 (17.6-26.1) | |

| Fair | 73.7 (65.4-80.7) | 26.3 (19.3-34.6) | |

| Poor | 74.0 (59.8-84.5) | 26.0 (15.5-40.2) | |

| Self-rated near vision | |||

| Excellent | 88.2 (84.4-91.2) | 11.8 (8.8-15.6) | <.001 |

| Very good | 84.8 (81.6-87.5) | 15.2 (12.5-18.4) | |

| Good | 82.4 (77.9-86.0) | 17.7 (14.0-22.1) | |

| Fair | 71.5 (65.0-77.2) | 28.5 (22.8-35.0) | |

| Poor | 74.7 (65.6-82.1) | 25.3 (17.9-34.4) | |

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 80.4 (78.0-82.5) | 19.6 (17.5-22.0) | <.001 |

| Yes | 91.3 (87.7-93.9) | 8.7 (6.1-12.3) | |

| Age-related eye diseasec | |||

| No | 78.3 (75.8-80.7) | 21.7 (19.3-24.2) | <.001 |

| Yes | 93.4 (90.6-95.4) | 6.6 (4.6-9.4) | |

| Not sure | 77.8 (62.7-87.9) | 22.2 (12.1-37.3) | |

Calculated using design-adjusted Pearson χ2 tests.

A total of 2013 individuals completed the survey; however, 2007 provided complete data on receipt of eye examinations.

Self-reported diagnosis of cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, or diabetic eye disease.

Table 2. Factors Associated With Undergoing an Eye Examination in the Past 2 Years Among US Older Adults.

| Factor | Recent Eye Examination | |

|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI)a | P Value | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | |

| Female | 2.00 (1.50-2.67) | <.001 |

| Age, y | ||

| 50-64 | 1 [Reference] | |

| 65-80 | 1.19 (0.83-1.69) | .34 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 1 [Reference] | |

| Black | 1.33 (0.80-2.23) | .28 |

| Hispanic | 1.25 (0.77-2.03) | .37 |

| Other | 0.762 (0.40-1.26) | .42 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 1 [Reference] | |

| Retired | 1.07 (0.72-1.59) | .74 |

| Not working at this time | 0.66 (0.42-1.04) | .07 |

| Annual household income, $ | ||

| <30 000 | 1 [Reference] | |

| ≥30 000 | 1.57 (1.08-2.29) | .02 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or partnered | 1 [Reference] | |

| Not married or partnered | 0.71 (0.53-0.96) | .03 |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 1 [Reference] | |

| Midwest | 0.55 (0.34-0.87) | .01 |

| South | 0.66 (0.43-1.02) | .06 |

| West | 0.60 (0.38-0.94) | .03 |

| Self-rated distance vision | ||

| Excellent or very good | 1 [Reference] | |

| Good | 0.59 (0.43-0.82) | .002 |

| Fair or poor | 0.43 (0.28-0.65) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 2.30 (1.50-3.54) | <.001 |

| Age-related eye disease | ||

| No or not sure | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 3.67 (2.37-5.69) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: AOR, adjusted odds ratio.

Odds ratios are adjusted for all other variables listed in this table.

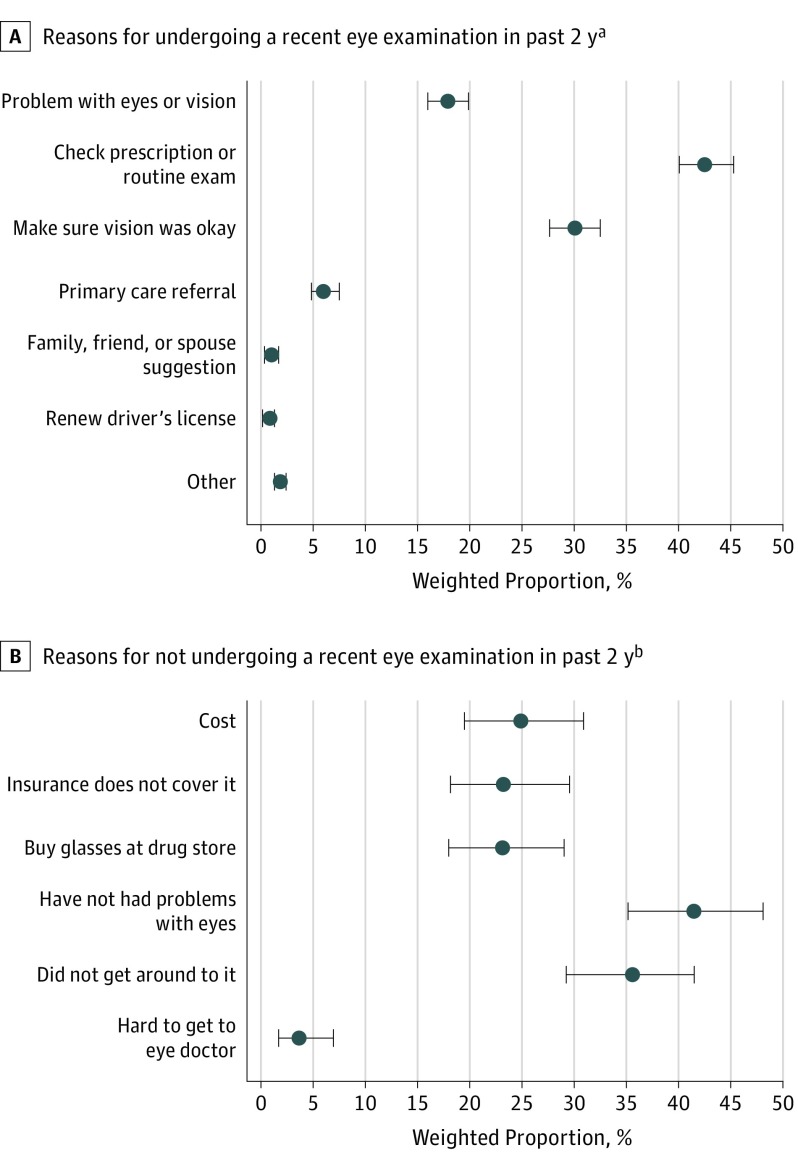

Reasons cited for undergoing and not undergoing a recent eye examination are depicted in the Figure. Respondents who underwent a recent eye examination did so most frequently to “check their glasses or contact lens prescription” and/or “for routine care” (42.5%). Respondents who did not undergo a recent eye examination most frequently reported they “had not had problems with their eyes” (41.5%). Respondents with lower household incomes were more likely to cite cost (income <$30 000, 34.3%; vs income ≥$30 000, 17.8%; P = .05) and lack of insurance coverage (income <$30 000, 37.4%; vs income ≥$30 000, 16.5%; P = .01) as reasons for not receiving recent eye care.

Figure. Reasons Reported for Obtaining and Not Obtaining Recent Eye Care Among Older US Adults Aged 50 to 80 Years.

Proportions are weighted to represent the total population of US adults aged 50 to 80 years. Error bars indicate 95% CIs, and eye doctor indicates ophthalmologist or optometrist.

aRespondents were asked to select the main reason for receiving eye care.

bRespondents were asked to select the reason(s) they had not received eye care.

Discussion

This nationally representative survey provides contemporary data on self-reported use of eye care for adults aged 50 to 80 years. Although most respondents reported receiving recent eye care, 27.8% of those with diabetes had not undergone an eye examination in the past year, and there were sociodemographic differences in the self-reported receipt of eye care.

The frequency of eye care in the past year was similar to that reported in some prior nationally representative studies.4,13 Among the 17.6% respondents who had not had an eye examination in the past 2 years in this study, the most commonly cited reason was that they had not had problems with their eyes. However, common progressive conditions such as glaucoma may be present and treatable before symptoms occur. Nonetheless, guidelines for routine preventive eye care remain controversial and the US Preventive Services Task Force states that there is insufficient evidence to support routine vision screening in older adults.14 Accordingly, future research should develop and evaluate optimized screening protocols that prevent vision loss and maintain quality of life, even in the absence of known vision problems.

For adults with diabetes, both the American Diabetes Association and American Academy of Ophthalmology recommend eye examinations at least annually.15,16 Studies using older data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey17 and Medicare claims18 reported that approximately 60% of adults with diabetes had undergone an eye examination in the prior year. The fact that respondents with diabetes in our study reported more frequent eye examinations is encouraging and may reflect public health messaging or improved access to care. Future studies should use both self-reported data and administrative claims to examine adherence with eye examination recommendations.

There is some disagreement on the association of race/ethnicity with use of eye care. Our study, like some prior investigations, failed to detect such an association,7 while others have reported both higher5 and lower13 use of eye care among racial/ethnic minorities. Additional work is needed to better characterize the association between race/ethnicity and eye care and determine whether it varies by socioeconomic status, geography, age, or other key factors that could help target those most at risk for not receiving eye care. In addition, observed differences related to sex, marital status, income, and geography may suggest the need for focused policy changes and public health messaging.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. Surveys are subject to recall, desirability, and healthy respondent biases. Adults with vision impairment may have been less likely to participate in the survey because it was administered online. Also, it was not possible to determine the need for eye examinations or infer causation from these data.

Conclusions

These contemporary data on self-reported use of eye care may help inform public health approaches to promote eye health and improve health equity for an aging population. Policy changes to encourage eye care for those at greatest risk for vision problems may be warranted. Additional studies using both survey and claims data are needed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the association of health policy changes with trends in vision health and the use of eye care.

eAppendix. National Poll on Healthy Aging Vision Module

References

- 1.Rein D, Wittenborn J Cost of vision problems: the economic burden of vision loss and eye disorders in the United States. https://www.preventblindness.org/sites/default/files/national/documents/Economic%20Burden%20of%20Vision%20Final%20Report_130611_0.pdf. Published June 11, 2013. Accessed September 15, 2018.

- 2.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Making Eye Health a Population Health Imperative: Vision for Tomorrow. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou C-F, Barker LE, Crews JE, et al. . Disparities in eye care utilization among the United States adults with visual impairment: findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system 2006-2009. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(6)(suppl):S45-52.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Cotch MF, Ryskulova A, et al. . Vision health disparities in the United States by race/ethnicity, education, and economic status: findings from two nationally representative surveys. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(6 suppl):S53-S62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner LD, Rein DB. Attributes associated with eye care use in the United States: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(7):1497-1501. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou C-F, Sherrod CE, Zhang X, et al. . Barriers to eye care among people aged 40 years and older with diagnosed diabetes, 2006-2010. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):180-188. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willis JR, Doan QV, Gleeson M, et al. . Self-reported healthcare utilization by adults with diabetic retinopathy in the United States. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2018;25(5-6):365-372. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2018.1489970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National poll on healthy aging. University of Michigan website. https://www.healthyagingpoll.org/. Accessed May 22, 2019.

- 9.Focus on aging eyes. poll finds primary care providers play a key role in vision care after 50. University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation website. https://ihpi.umich.edu/news/focus-aging-eyes-poll-finds-primary-care-providers-play-key-role-vision-care-after-50. Published September 5, 2018. Accessed May 22, 2019.

- 10.GfK KnowledgePanel: a methodological overview. https://www.gfk.com/fileadmin/user_upload/dyna_content/US/documents/KnowledgePanel_-_A_Methodological_Overview.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2019.

- 11.Callegaro M, DiSogra C. Computing response metrics for online panels. Public Opinion Q. 2008;72(5):1008-1032. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfn065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heeringa S, West B, Berglund P. Applied Survey Data Analysis. Second. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varadaraj V, Frick KD, Saaddine JB, Friedman DS, Swenor BK. Trends in eye care use and eyeglasses affordability: the US national health interview survey, 2008-2016 [published online January 24, 2019]. JAMA Ophthalmol. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.6799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Preventive Services Task Force Final recommendation statement: impaired visual acuity in older adults: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/impaired-visual-acuity-in-older-adults-screening. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 15.Feder RS, Olsen TW, Prum BE Jr, et al. . Comprehensive adult medical eye evaluation preferred practice pattern guidelines. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(1):209-236. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Diabetes Association Eye care. http://www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/complications/eye-complications/eye-care.html. Accessed October 13, 2018.

- 17.Bressler NM, Varma R, Doan QV, et al. . Underuse of the health care system by persons with diabetes mellitus and diabetic macular edema in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(2):168-173. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.6426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee PP, Feldman ZW, Ostermann J, Brown DS, Sloan FA. Longitudinal rates of annual eye examinations of persons with diabetes and chronic eye diseases. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(10):1952-1959. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00817-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. National Poll on Healthy Aging Vision Module