Abstract

Purpose:

To report the incidence, demographics, and ocular findings of children with myasthenia

Design:

Retrospective cohort study

Methods:

The medical records of all children (< 19 years) examined at Mayo Clinic with any form of myasthenia from January 1 1966, through December 31, 2015, were retrospectively reviewed.

Results:

A total of 364 children were evaluated during the study period, of which 6 children were residents of the Olmsted County at the time of their diagnosis, yielding an annual age- and sex-adjusted incidence of 0.35 per 100,000 <19 years, or 1 in 285,714 <19 years. The incidence of juvenile myasthenia gravis (JMG) and congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS) was 0.12 and 0.23 per 100,000, respectively. Of the 364 study children, 217 (59.6%) had JMG, 141 (38.7%) had CMS, and 6 (1.7%) had Lambert-Eaton syndrome, diagnosed at a median age of 13.5, 5.1, and 12.6 years, respectively. A majority of the JMG and CMS patients had ocular involvement (90.3 and 85.1% respectively), including ptosis and ocular movement deficits. Among children with at least one year of follow-up, (JMG; median, 7.1 years, CMS; median, 7.0 years) improvement was seen in 88.8% of JMG patients (complete remission in 31.3%) and in 58.3% of CMS patients.

Conclusion:

Although relatively rare, myasthenia gravis in children has two predominant forms, CMS and JMG, both of which commonly have ocular involvement. Improvement is more likely in children with the juvenile form.

Myasthenia gravis is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by fluctuating weakness and fatigability of the voluntary muscles of the body.1 Pediatric myasthenia is a common term for disease onset prior to 19 years of age and includes both the autoimmune and inherited etiologies.2 Pediatric myasthenia is divided into neonatal, congenital, and juvenile forms. Congenital myasthenic syndrome includes a diverse group of inherited disorders, typically present at birth, caused by a defective signal transmission at the neuromuscular junction.3 Juvenile myasthenia is caused by an ongoing production of autoantibodies directed against the post synaptic membrane of the neuro-muscular junction, while neonatal myasthenia is a transient condition occurring due to the passive transfer of antibodies from the myasthenic mother.2

While adult myasthenia gravis is a more prevalent disease and has been studied in several populations, less is known about the juvenile form,4,5 with incidences rates varying widely between geographic regions.6-8 Even less is known concerning congenital myasthenic syndrome. The purpose of this study is to describe the incidence, demographics and ocular findings of myasthenia gravis observed in patients <19 years of age over a 50-year period.

Methods

The medical records of all patients less than 19 years of age who were diagnosed with any form of myasthenia gravis from January 1, 1966, through December 31, 2015, and examined at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, were retrospectively reviewed. Patients diagnosed while residing in Olmsted County, Minnesota were identified using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, a medical record linkage system designed to capture data on any patient–physician encounter in Olmsted County, Minnesota.9 The population of Olmstead County is relatively isolated from other urban areas and virtually all medical care is provided to its residents by Mayo Clinic, Olmsted Medical Group, and their affiliated hospitals. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Group.

A diagnostic code search was performed using the Rochester Epidemiology Project and Mayo Clinic databases, applying a wide range of myasthenia-related codes in order to capture all patients with myasthenia. Of the 544 potential patients identified through the search, 145 were excluded due to incorrect diagnosis, 17 presented to Mayo Clinic facilities outside of Minnesota, 8 were not within the study period, 6 were 19 years or older at the time of diagnosis, and 4 had incomplete medical records. The remaining 364 patients were included in the study. Pediatric myasthenia patients included all patients with symptoms and/or signs of ocular or generalized weakness fulfilling the criteria of diagnosis of juvenile myasthenia gravis (JMG), congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS), neonatal transient myasthenia gravis (MG) or acquired Lambert-Eaton myasthenia (LEM).

The diagnosis of JMG was assigned when symptoms typical for MG were present such as fatiguable ocular or generalized weakness with onset before 19 years of age, along with two of the following three features: 6 1. antibodies against acetylcholine receptors (AchR) or muscle- specific kinase (MuSK), 2. electrophysiological findings of decrement on repetitive stimulation and/or increased jitter of single-fiber electromyography (EMG), and 3. response to administration of acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and/or immunomodulating therapy. A diagnosis of ‘probable JMG’ was made when one of the three criteria was met in the setting of a clinical picture consistent with the diagnosis JMG by the treating neurologist or ophthalmologist. CMS was diagnosed on the basis of ocular or generalized weakness present from birth or early life along with any one of the following:-3 1.supportive clinical or in-vitro electrophysiological studies, 2. supportive muscle biopsy findings, and 3. molecular genetic testing showing mutations in the CMS genes. The diagnosis of ‘probable CMS’ was assigned when there was no supportive testing, but the clinical picture was considered consistent with the diagnosis CMS by the treating neurologist or ophthalmologist. The diagnosis of transient neonatal MG was assigned when there were findings of weakness in the neonate born to a mother with myasthenia gravis, with AchR antibodies with resolution of weakness within 3 months.1

Each record was meticulously reviewed for confirmation of myasthenia gravis based on the criteria listed above. The 364 medical records were reviewed for demographics including sex, race, date of diagnosis, history of prematurity, date of onset, symptoms at onset, date of presentation, symptoms and signs at presentation, laboratory tests, imaging, electrophysiological studies, genetic tests and recommended treatment. The ophthalmic record was reviewed for visual acuity, ocular misalignment, extraocular movement abnormalities, and anterior and posterior segment findings. Longitudinal findings were collected from follow-up examinations and letters of communication from referring physicians as well as parent and patient questionnaire’s that were part of the medical record.

An outcome was designated as ‘complete remission’ when a patient had no symptoms or signs for at least 1 year and received no therapy for MG during the same period, while pharmacologic remission’ referred to those patients who were symptom-free on medical therapy. ‘Minimal manifestation’ included those patients who had no symptom of functional limitations caused by MG but had findings consistent with muscle weakness due to either the disease itself or the use of immunosuppression and/ or cholinesterase inhibitors. Since the treatment drugs themselves can cause muscle weakness as a side effect, ‘minimal manifestation’ was made a separate category. Patients experiencing an improvement in signs and symptoms not included in any of the above 3 categories where considered “improved”, while ‘unchanged’ or ‘worsened’ was defined for no change or worsening of signs and symptoms, respectively, between the initial and final follow-up evaluation.10

The prevalence and incidence of pediatric myasthenia gravis its subtypes was estimated using the population figures in Olmsted County. Population figures for 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 and 2010 were based on the US census data, and population figures for the inter-census years were estimated by linear interpolation. These incidence rates were also age- and/or sex-adjusted to the 2010 census figures for the U.S. white population to enable comparison with national estimates. The 95% confidence interval for the overall incidence was then calculated to provide range of the true incidence. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Caroline).

Results

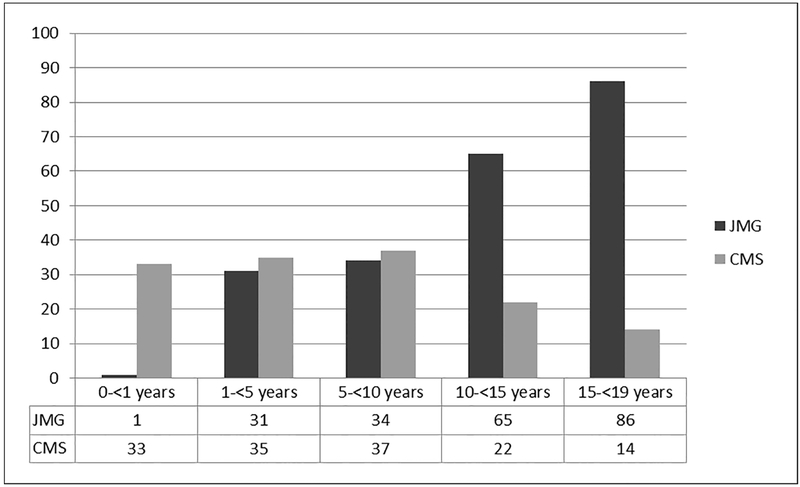

Three hundred sixty-four children were evaluated for myasthenia during the 50-year study, of which 217 (59.6%) had juvenile myasthenia gravis (JMG), 141 (38.7%) had congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS), and 6 (1.7%) had Lambert-Eaton syndrome (LES). Demographic features and ocular characteristics of the 364 patients are summarized in Table 1. Fourteen (6.5%) of the 217 JMG patients were diagnosed as probable JMG and one (0.7%) of the 141 CMS patients were diagnosed as probable CMS. There were no children with the diagnosis of neonatal transient myasthenia. Two hundred nineteen (60.2%) were females with 144 (66.4%) in the JMG cohort, 74 (52.5%) in the CMS cohort and 1 (16.7%) in the LES cohort. CMS was diagnosed at a median age of 5.1 years (range, 0 to 18.9 years) whereas JMG was diagnosed at a median age of 13.5 years (range, 0.9 to 18.8 years) as illustrated in Figure 1. LES was diagnosed at a mean age of 12.6 years (range, 7.6 to 17.7 years). The median duration from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 5.0 months (range, birth to 18.9 years).

Table 1.

Historical and demographic characteristics of 364 children diagnosed with myasthenia gravis from 1966 through 2015

| No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | JMG (N=217) |

CMS (N=141) |

LEM (N=6) |

Overall (N=364) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 73 (33.6) | 67 (47.5) | 5 (83.3) | 145 (39.8) |

| Female | 144 (66.4) | 74 (52.5) | 1 (16.7) | 219 (60.2) |

| Race | ||||

| African American | 5 (2.3) | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (2.5) |

| Asian | 6 (2.8) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (2.2) |

| Caucasian | 136 (62.7) | 93 (66.0) | 6 (100.0) | 235 (64.4) |

| Unspecified | 67 (30.9) | 42 (29.8) | 0 (0.0) | 109 (29.9) |

| Prematurity* | ||||

| Yes | 10 (4.6) | 11 (7.8) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (5.8) |

| Family history | ||||

| Myasthenia | 4 (1.8) | 26 (18.4) | 0 (0.0) | 30 (8.2) |

| Consanguinity | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.8) |

| Age at onset in years | ||||

| Median (range) | 12.8y (0.8-18.3) | 0y (0.0-13.3) | 9.5y (0.0-14.8) | 5.8y (0.0-18.3) |

| Age at diagnosis in years | ||||

| Median (range) | 13.5y (0.9-18.8) | 5.1y (0.0-18.9) | 12.6y (7.6- 18.7) | 10.8y (0.0-18.9) |

| Symptoms at onset | ||||

| Weakness | 71 (32.7) | 37 (26.2) | 5 (83.3%) 1 | 113 (31.0) |

| Drooping of eyelids | 111 (51.2) | 45 (31.9) | (16.7) | 157 (43.1) |

| Diplopia | 52 (24.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 52 (14.3) |

| Swallowing, chewing, speech difficulties | 54 (24.9) | 23 (16.3) | 0 (0.0) | 77 (21.2) |

| Floppy baby | 1 (0.5) | 21 (14.9) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (6.0) |

| Feeding difficulties | 1 (0.5) | 62 (44.0) | 1 (16.7) | 64 (17.6) |

| Respiratory difficulties | 7 (3.2) | 54 (38.3) | 0 (0.0) | 61 (16.8) |

| Involvement | ||||

| Ocular predominantly | 49 (22.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 49 (13.5) |

| Bulbar predominantly | 4 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.1) |

| Ocular & Bulbar | 16 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (4.4) |

| Generalized | 148 (68.2) | 141 (100) | 6 (100) | 295 (81.0) |

| Vision | ||||

| Amblyopia | 12 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (3.3) |

| Ptosis at presentation | ||||

| Unilateral | 29 (13.4) | 8 (5.7) | 1 (16.7) | 38 (10.4) |

| Bilateral | 113 (52.1) | 95 (67.4) | 2 (33.3) | 210 (57.7) |

| Strabismus at presentation | ||||

| Esotropia | 21 (9.7) | 11 (7.8) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (8.8) |

| Exotropia | 15 (6.9) | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (4.9) |

| Vertical deviation | 17 (7.9) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (4.9) |

| Strabismus, not specified | 5 (2.3) | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (2.5) |

| Limitation of (OD or OS or OU) | ||||

| Adduction | 49 (22.6) | 56 (39.7) | 0 (0.0) | 105 (28.9) |

| Abduction | 54 (24.9) | 66 (46.8) | 0 (0.0) | 120 (33.0) |

| Elevation | 44 (20.3) | 63 (44.6) | 0 (0.0) | 107 (29.4) |

| Depression | 35 (16.1) | 47 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 82 (22.5) |

Born at <37 weeks

Figure 1.

Age at diagnosis for 217 children with JMG & 141 children with CMS from 1966 through 2015 at Mayo Clinic

Six of the 364 study children were residents of the Olmsted County at the time of their diagnosis, yielding an annual age- and sex-adjusted incidence of 0.35 (95% confidence interval: 0.07-0.63) per 100,000 <19 years, or 1 in 285,714 <19 years. Four children were diagnosed with CMS and 2 had JMG with an incidence of 0.23 and 0.12 per 100,000 <19 years, respectively (95% confidence intervals: 0.005-0.46 and 0-0.28). There were no cases of neonatal myasthenia gravis or pediatric Lambert-Eaton myasthenia in Olmsted County over the 50-year period. Both JMG children had ocular myasthenia and included one male and one female. Three of the 4 CMS children were siblings, two female and one male with post-synaptic disease and an abnormal beta subunit of acetylcholine receptors on muscle biopsy. If the 3 siblings with CMS are counted as a single family unit, the corrected annual age- and sex-adjusted incidence is 12 (95% confidence interval: 0.000-0.28) per 100,000 <19 years, or 1 in 50,582 live births. The final female with CMS had a synaptic form of the disease with muscle biopsy showing endplate acetylcholinesterase deficiency. All 4 patients with CMS had generalized disease including extraocular movement limitation and bilateral ptosis.

The ocular features observed among the cohort of 364 children are shown in table 1. At the time of onset, 180 (49.5%) had ocular symptoms by history with 25 children (6.9%) presenting to the ophthalmologist first. Drooping eyelids was the most common symptom at onset in the JMG and CMS groups (51.2% and 31.9%, respectively). Ocular signs and symptoms occurred in 90.3% of children with JMG and in 85.1% of those with CMS, while ocular features alone occurred in 22.6% and 0.0%, respectively. On examination, strabismus in primary position was present in 45 (20.7%) of the 217 with JMG and 18 (12.8%) of those with CMS (Table 1). Esotropia was the most frequent form of misalignment (JMG: 9.7% and CMS: 7.8%). Extraocular limitation of movements was found in 66 (30.4%) and 75 (53.2%) of the JMG and CMS groups, respectively. Ptosis was present in 65.5%, 73.1% and 50% in the JMG, CMS and LEM groups, respectively, with Cogan’s lid twitch occurring in 14 (3.8%) children, all in the JMG group. Amblyopia occurred in 12 (5.5%) in the JMG group.

Among the 217 children with JMG, electromyography was positive in 154 (82.8%), anticholinesterase serum antibodies occurred in 100 (68.5%), autoantibodies to muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (anti-MuSK) in 5 (26.3%) and anti-striational antibodies in 2 (8.3%) (Table 2). Thymus enlargement was present on imaging in 15 (7.9%), of the 194 (89.4%) children who were imaged. Of the 141 children with CMS, electromyography was positive in 136 (97.8%) of the 139 tested children and a causative gene mutation was identified in 37 (82.2%) of the 45 children tested. Of the 93 (66.0%) children in whom the level of transmission abnormality was identified by combined electrophysiological and structural or genetic studies, postsynaptic acetylcholine receptor defect was the most common seen in 51 patients (54.8%), followed by defects in endplate development and maintenance in 16 (17.2%). Fourteen (15.1%) had abnormalities in synaptic basal lamina associated proteins, 11 (11.8%) had abnormal presynaptic proteins, and 1 (1.1%) had defects in glycosylation. The ocular features among children with CMS were analyzed based on the level of transmission abnormality and is depicted in table 3. All the children with LEM had diagnostic electromyographs although only 2 of the 6 had positive Lambert-Eaton antibodies to the P/Q type calcium channels.

Table 2.

Clinical investigations of 217 children evaluated for juvenile myasthenia gravis from 1966 through 2015 at Mayo Clinic

| No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ocular myasthenia N=49 |

Generalized myasthenia N=148 |

Predominantly Bulbar * N=4 |

Predominantly ocular and bulbar* N=16 |

Overall N=217 |

|

| Tensilon test | |||||

| Positive | 36 (94.7) | 86 (96.6) | 3 (100) | 8 (80.0) | 133 (95.0) |

| Electromyography | |||||

| Positive | 19 (47.5) | 115 (91.3) | 4 (100.0) | 16 (100.0) | 154 (82.8) |

| Imaging | |||||

| Thymus enlargement | 2 (6.3) | 13 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (7.9) |

| Antibodies | |||||

| Anticholiesterase | 20 (60.6) | 73 (72.3) | 1 (100) | 6 (54.6) | 100 (68.5) |

| Anti-MuSK | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) | 5 (2.3) |

| Anti-striational | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) |

| Seronegative | 13 (39.4) | 26(25.7) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (45.5) | 44 (30.1) |

Oropharyngeal muscle involvement

Table 3.

Ocular findings amongst 141 children diagnosed with congenital myasthenic syndrome from 1966 through 2015 at Mayo Clinic

| No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ptosis | Extraocular movement limitation |

Strabismus | Overall N=141 |

|

| Presynaptic N=11 | 7 (63.6) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) | |

| ChAT deficiency | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| SNAP25B | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 5 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Postsynaptic N=51 | 46 (90.2) | 46 (90.2) | 4 (7.8) | |

| Alpha subunit defect | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Beta subunit defect | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Delta subunit defect | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Epsilon subunit defect | 9 | 9 | 1 | 9 |

| Slow channel | 11 | 12 | 3 | 14 |

| Fast channel | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Unknown | 19 | 17 | 0 | 20 |

| Synaptic N=14 | 11 (78.6) | 8 (57.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Collagen Q mutation | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Laminin B2 deficiency | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 9 | 7 | 0 | 12 |

| Endplate development and maintenance N=16 | 12 (75.0) | 3 (18.8) | 7 (43.8) | |

| Dok- 7 myasthenia | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Rapsn deficiency | 8 | 2 | 7 | 11 |

| MuSK deficiency | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Defects of glycosylation N=1 | ||||

| DPAGT1 myasthenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Indeterminate N=48 | 36 (75.0) | 22 (45.8) | 8 (16.7) | 48 |

The median follow-up duration for the 364 cases was 3.0 years (range, birth to 50.4 years) and 3.7 years (range, birth to 46.1 years) for the JMG and CMS cohorts, respectively. One hundred thirty-four (61.8%) of the children with JMG were followed for a minimum duration of one year with a median follow-up of 7.1 years (range, 1 to 50.4 years), while 96 (68.1%) of the 141 CMS patients were followed for a similar minimum duration, with a median of 7.0 years (range, 1.2 to 46.1 years). Sixty-seven (50.0%) of 134 JMG patients and 34 (35.4%) of 96 with CMS were determined by actual visits, while 67 (50.0%) of 134 and 62 (64.6%) of 96 were determined by letters of communication.

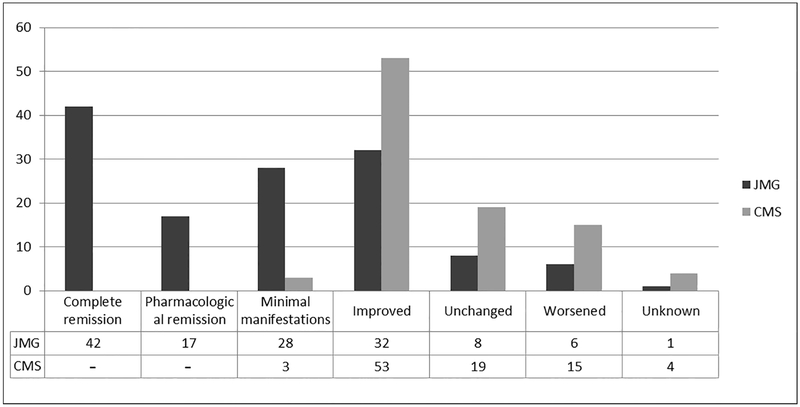

One hundred nineteen (88.8%) and 56 (58.3%) of patients with JMG and CMS, respectively, experienced some degree of improvement in symptoms from the initial presentation to the final follow-up. During this observation interval, complete remission occurred in 42 (31.3%) of patients with JMG and in none of patients with CMS, as expected. Figure 2 depicts the outcomes for the subgroups. Among the entire cohort of 364 children, 52 (14.3%) received prolonged intubation (>7 days) at some point during their follow up (JMG 10.1% and CMS 26.2%). Twelve patients (5.5%) with JMG required strabismus surgery, 2 (0.9%) were treated with botulinum toxin injections for strabismus and 1 (0.5%) patient underwent ptosis repair surgery. Among the CMS patients, 3 (2.1%) underwent strabismus surgery, while 6 (4.3%) had surgery for ptosis.

Figure 2.

Outcomes for 134 children with juvenile myasthenia gravis & 96 children with congenital myasthenic syndrome followed for at least 1 year from 1966 through 2015 at Mayo Clinic

Discussion

In this population-based study of children observed over a 50-year period, the incidence of childhood myasthenia was 0.35 per 100,000 <19 years. The incidence of juvenile myasthenia gravis (JMG) and congenital myasthenic syndromes (CMS) were 0.12 and 0.23 per 100,000, respectively. Of the 364 study children, about 60% were found to have JMG while nearly 40% had CMS. Lambert-Eaton comprised less than 2 percent of the study cohort. Ocular involvement occurred in approximately 9 out of 10 patients with both JMG and CMS. Among those children observed for at least one year, most children improved including complete remission in only one-third of children with JMG.

The incidence of JMG in this study is similar to Popperud et al and Parr et al, who reported an incidence of 1.6 per million and 1.5 per million, respectively,6,11 but less than the 3.85-7.85 per million children reported by Tsai et al in the Taiwanese population.8 However, Asian populations have described a higher proportion of childhood-onset myasthenia gravis.4 An epidemiological study from Virginia in the United States describes the incidence of autoimmune myasthenia gravis as 9.1 per million per year with 13.7% having onset prior to 19 years of age, although they did not report the incidence in the pediatric population.12 A study based on voluntary reporting of cases from Canada reported an incidence of 0.9 to 2.0 per 1 million children per year, which was similar to our rate.7

Our incidence rate of congenital myasthenic syndrome was as high as the rate of JMG in the current population. There are limited epidemiologic studies with which to compare these findings. One report from the United Kingdom observed a prevalence of 9.2 genetically confirmed cases per million under 18 years of age. 11 They included identified children from the laboratory performing genetic testing for CMS for all of the UK, and therefore they could have missed patients with clinical findings and other testing indicating CMS, but who had not had the CMS mutation determined.

The initial clinical and ocular features of the 217 children with JMG were generally similar to prior reports. Popperud et al and Parr et al reporting on children diagnosed at a mean age of 13 years, reported similar findings in predominantly Caucasian populations, while Tsai et al reported younger age at diagnosis (mean 8.7 years) in an Asian population.6,8,11 There was, similar to prior studies,8,11 a preponderance of females in this cohort of patients. Atopic diseases and asthma were found to be more common in children with myasthenia in a previous study.8 Though our study had no comparison cohort, the (6 (2.8%) and 10 (4.6%) of the JMG cohort had allergies and asthma respectively). Fifteen (7.9%) of the study patients had evidence of thymic enlargement, while Tsai et al found that none of their patients had benign or malignant tumor of the thymus.8 This difference could be explained by referral patterns to our institution of complex myasthenia or for thymus surgery. Seventy-five percent of our children in our study had ocular symptoms of ptosis and diplopia at the time of onset of the disease. This finding is similar to Popperud et al who found that 69% had an initial ocular manifestation.6 Amblyopia in our cohort was uncommon (5.5%) compared to Pineles et al who reported that 26% had amblyopia initially, declining to 3% after treatment.10 Antibodies to acetylcholine receptors were positive in 82.8% of our patients overall and in 47.5% of our patients with ocular myasthenia, similar to the diagnostic sensitivity in adult populations. 13 Rates of remission reported in literature vary widely from 12% to 70% in various populations; with our findings (31.3%) being similar to Pineles et al (26%), although they included only ocular myasthenia patients.14-16

Similarly, the clinical and ocular features of CMS in this cohort were not unlike prior reports. Among our CMS group, the median age at onset was at birth which is similar to previous studies.17 There was, similar to previous studies, nearly equal distribution among the two sexes.11 A previous study performed from Mayo clinic described a series of 295 patients with CMS, which included patients that were investigated at Mayo using DNA sent by other centers, but not necessarily examined. Among the CMS study cohort, a large majority had ptosis across most subtypes, while about half demonstrated ophthalmoparesis, similar to what has been described previously in literature.17,18 We found that three-fourths of our patients had an unchanged or improved course. Regarding other types of myasthenia, we found no patients in the population-based cohort with Lambert-Eaton syndrome and very few patients with confirmed antibody positive Lambert-Eaton myasthenia overall (2 cases over a 50-year period), similar to a recent report.19 We did not report a single case of neonatal autoimmune myasthenia, similar to a study in the UK that found neonatal myasthenia to be extremely rare (3 children per year).11

There are a number of limitations to the findings of this study. Its retrospective design is limited by incomplete data and variable follow up. Second, serology studies to detect anticholinesterase antibodies were not available during the early years of this study and thus, many children at that time were diagnosed based on clinical features alone. Additionally, because the definition of pediatric myasthenia gravis evolved over the 50-year study period, we retrospectively applied diagnostic criteria in a uniform manner to each medical record to establish the diagnosis. The incidence rate from this cohort may be lower than the true value because some children with mild disease may have gone unnoticed and some residents of Olmsted County may have sought care outside the study catchment area. Similarly, not all patients were examined by an ophthalmologist. While this report is only the second study to assess epidemiological data on CMS, the measured confidence interval was wide and included the value of zero. A small total population like that of Olmsted County makes it difficult to study rare diseases and therefore, we chose to extend the database over a 50-year period. Additionally, longitudinal data collected from local physician letters and patient communications may be prone to inaccuracies. However, because our institution is a referral center, we felt it important to include data from the referring physician letters to minimize the referral bias inherent by including only those patients seen in follow-up at our institution. If the letter of communication did not contain sufficient evidence to categorize an outcome based on our definitions, the patient was excluded from our outcome assessment. Finally, given the small number of Olmsted County residents, the findings in this population may not be generalizable to other populations.

Pediatric myasthenia gravis was found to occur rarely in this population and was principally comprised of two predominant forms: congenital myasthenic syndrome and juvenile myasthenia gravis. JMG was more prevalent among girls while CMS was nearly equally distributed among the sexes. Eighty-five to nighty percent had ocular involvement during the course of the disease. Complete remission occurred in about one-third of the children with JMG and in none of the children with CMS during the study period.

In this cohort of 364 children with myasthenja, the two predominant forms, juvenile myasthenia gravis and congenital myasthenic syndrome, demonstrated ocular involvement in 90% and 85%, respectively, with improvement in 88.8% and 58.3% over a median follow up duration of 3.0 and 3.7 years, respectively.

Acknowledgement

Funding/ Support: This study was made possible in part by the Rochester Epidemiology Project [Grant # R01-AG034676 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases], and by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, NY.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None of the authors have any financial disclosures

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Berrih-Aknin S, Frenkian-Cuvelier M, Eymard B. Diagnostic and clinical classification of autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evoli A. Acquired myasthenia gravis in childhood. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23(5):536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engel AG, Shen X-M, Selcen D, Sine SM. Congenital myasthenic syndromes: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(4):420–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr AS, Cardwell CR, McCarron PO, McConville J. A systematic review of population based epidemiological studies in Myasthenia Gravis. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee HN, Kang H-C, Lee JS, et al. Juvenile Myasthenia Gravis in Korea: Subgroup Analysis According to Sex and Onset Age. J Child Neurol. 2016;31(14):1561–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popperud TH, Boldingh MI, Brunborg C, et al. Juvenile myasthenia gravis in Norway: A nationwide epidemiological study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017;21(2):312–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.VanderPluym J, Vajsar J, Jacob FD, Mah JK, Grenier D, Kolski H. Clinical characteristics of pediatric myasthenia: a surveillance study. Pediatrics. 2013; 132(4):e939–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai J-D, Lin C-L, Shen T-C, Li T-C, Wei C-C. Increased subsequent risk of myasthenia gravis in children with allergic diseases. J Neuroimmunol. 2014;276(1-2):202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurland LT, Molgaard CA. The patient record in epidemiology. Sci Am. 1981. ;245(4):54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pineles SL, Avery RA, Moss HE, et al. Visual and systemic outcomes in pediatric ocular myasthenia gravis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(4):453–459.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parr JR, Andrew MJ, Finnis M, Beeson D, Vincent A, Jayawant S. How common is childhood myasthenia? The UK incidence and prevalence of autoimmune and congenital myasthenia. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(6):539–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillips LH, Torner JC, Anderson MS, Cox GM. The epidemiology of myasthenia gravis in central and western Virginia. Neurology. 1992;42(10):1888–1893.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evoli A. Myasthenia gravis: new developments in research and treatment. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30(5):464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morita MP, Gabbai AA, Oliveira AS, Penn AS. Myasthenia gravis in children: analysis of 18 patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2001;59(3-B):681–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raksadawan N, Kankirawatana P, Balankura K, Prateepratana P, Sangruchi T, Atchaneeyasakul L-O. Childhood onset myasthenia gravis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85 Suppl 2:S769–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gui M, Luo X, Lin J, et al. Long-term outcome of 424 childhood-onset myasthenia gravis patients. J Neurol. 2015;262(4):823–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aharoni S, Sadeh M, Shapira Y, et al. Congenital myasthenic syndrome in Israel: Genetic and clinical characterization. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27(2):136–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abicht A, Dusl M, Gallenmuller C, et al. Congenital myasthenic syndromes: achievements and limitations of phenotype-guided gene-after-gene sequencing in diagnostic practice: a study of 680 patients. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(10):1474–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan-Followell B, de Los Reyes E. Child neurology: diagnosis of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome in children. Neurology. 2013;80(21):e220–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]