Summary

Regulatory T (Treg) cells play a crucial role in maintaining self‐tolerance and resolution of immune responses by employing multifaceted immunoregulatory mechanisms. However, Treg cells readily infiltrate into the tumor microenvironment (TME) and dampen anti‐tumor immune responses, thereby becoming a barrier to effective cancer immunotherapy. There has been a substantial expansion in the development of novel immunotherapies targeting various inhibitory receptors (IRs), such as CTLA4, PD1 and LAG3, but these approaches have mechanistically focused on the elicitation of anti‐tumor responses. However, enhanced inflammation in the TME could also play a detrimental role by facilitating the recruitment, stability and function of Treg cells by up‐regulating chemokines that promote Treg cell migration, and/or increasing inhibitory cytokine production. Furthermore, IR blockade may enhance Treg cell function and survival, thereby serving as a resistance mechanism against effective immunotherapy. Given that Treg cells are comprised of functionally and phenotypically heterogeneous sub‐populations that may alter their characteristics in a context‐dependent manner, it is critical to identify unique molecular pathways that are preferentially used by intratumoral Treg cells. In this review, we discuss markers that serve to identify certain Treg cell subsets, distinguished by chemokine receptors, IRs and cytokines that facilitate their migration, stability and function in the TME. We also discuss how these Treg cell subsets correlate with the clinical outcome of patients with various types of cancer and how they may serve as potential TME‐specific targets for novel cancer immunotherapies.

Keywords: chemokine/chemokine receptors, cytokines, inhibitory/activating receptors, regulatory T cells, tumor immunology

Introduction

Regulatory T (Treg) cells are a subset of CD4+ T cells characterized by their expression of a key transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FoxP3).1 Treg cells play a crucial role in the maintenance of self‐tolerance and resolution of inflammation.2 Mutations within the Foxp3 gene result in defective Treg cell development, leading to lethal systemic auto‐immune diseases in both humans3 and mice.4 Treg cells regulate immune responses through four major mechanisms: metabolic regulation, direct cytolysis, regulation of antigen‐presenting cells, and secretion of inhibitory cytokines.2

However, Treg cells play a detrimental role in the context of cancer. Treg cells readily infiltrate into the tumor microenvironment (TME) and play a significant role in suppressing anti‐tumor immune responses,5, 6, 7, 8 making them a barrier to effective cancer immunotherapy. Indeed, an increase in intratumoral Treg cells has been correlated with poor patient prognosis in many cancer types, including ovarian carcinoma.5 However, there have been reports suggesting that the infiltration of FoxP3+ Treg cells can be a favorable prognostic marker for certain types of cancer, such as colorectal cancer,9 although this may also be an indirect consequence of enhanced overall T‐cell infiltration. Importantly, while Foxp3 expression is a faithful marker to identify Treg cells in mice, human FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells are not necessarily a homogeneously immunosuppressive population. Human FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells can be stratified into three subsets: CD45RA+ FoxP3lo (resting Treg cells), CD45RA− FoxP3hi (activated Treg cells) and CD45RA− FoxP3lo subsets,10 with the latter representing recently activated effector T cells with up‐regulated expression of pro‐inflammatory cytokines.11 Indeed, enrichment of the CD45RA− FoxP3lo subset in the TME has been associated with long‐term disease‐free survival of patients with colorectal cancer,6 suggesting that previously reported beneficial prognostic correlation with intratumoral FoxP3+ T cells may have been due to a CD45RA− FoxP3lo effector subset. Hence, activated Treg cell infiltration may be detrimental across all types of cancer.

Treg cells are functionally and phenotypically heterogeneous, altering their ‘flavor’ in a context‐dependent manner,11 and it is unclear which suppressive mechanism(s) plays a dominant role in the TME. Furthermore, it remains elusive whether distinct subsets of Treg cells exist, or if there is phenotypic plasticity that is modulated based on the microenvironment. It is also unclear if the same or different subpopulations differentially use these regulatory mechanisms. In this review, we focus on key cell surface markers or secreted proteins that have a key impact on the identity and function of different Treg cell subsets, facilitating their infiltration, stability and/or regulatory functions in the TME. We will also discuss correlations between these Treg cell subsets and patient clinical outcome, as well as the development of therapeutic approaches targeting these key cell surface markers or secreted proteins.

Chemokine receptors

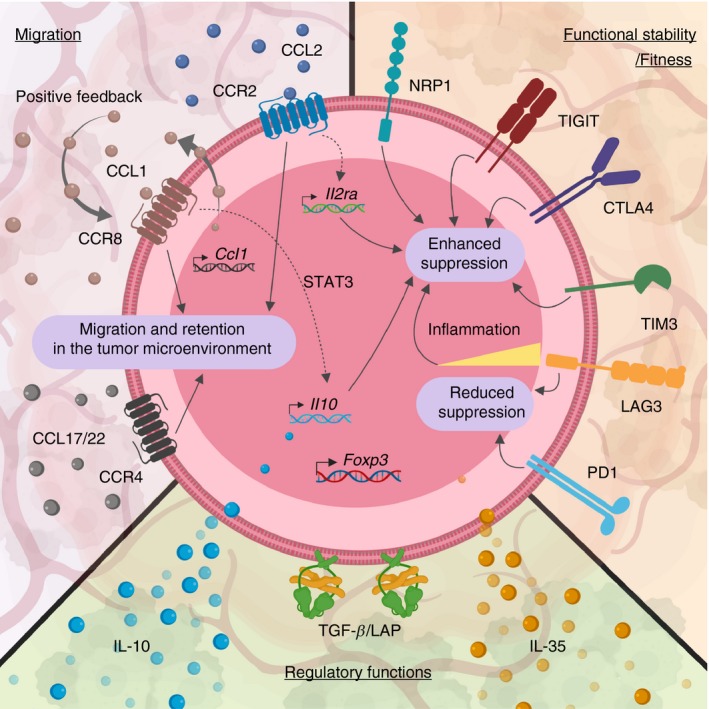

Although Treg cells prevent catastrophic systemic autoimmunity,4 their migratory capacity is a key factor impacting their ability to regulate tissue‐restricted inflammation. Targeting chemokine receptors that are preferentially used by tumor‐infiltrating Treg cells may therefore be an attractive approach to elicit beneficial anti‐tumor immune responses in patients. In this section, we review Treg cell subsets characterized by selective upregulation of C‐C chemokine receptors and potential therapeutic opportunities to target these Treg cell subsets (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Subset stratification of intratumoral regulatory T (Treg) cells. Heterogeneous intratumoral Treg cells can be characterized based on their expression pattern on functional surface molecules or secretion of inhibitory cytokines. Activated Treg cells up‐regulate various chemokine receptors in a context‐dependent manner to home to the site of inflammation. Some chemokine receptors, such as CCR8, have been shown to also support Treg function and stability in addition to providing chemotactic navigation to guide Treg cells to the tumor microenvironment (TME). Furthermore, Treg cells also up‐regulate numerous inhibitory receptors (IRs), including PD1 and LAG3. Although many of these IRs have been associated with dysfunctional, exhausted CD8+ tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), the exact cell‐intrinsic role(s) of IRs in intratumoral Treg cells have not been fully elucidated. Some IRs, such as TIGIT, maintain and promote the suppressive function of Treg cells, whereas other IRs, including PD1 and LAG3, have been associated with a reduced suppressive activity of Treg cells. Lastly, there are divergent subpopulations of intratumoral Treg cells secreting different inhibitory cytokines, such as transforming growth factor‐β (TGF‐β), interleukin‐10 (IL‐10) and IL‐35.

C‐C chemokine receptor 2

C‐C chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) plays a critical role in the migration of Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes through interaction with its ligands C‐C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) and CCL7.12 However, recent studies have demonstrated a chemotactic role for CCR2 in T cells during inflammation.13 Interestingly, a subset of CCR2+ Treg cells was enriched in both tumor and draining lymph nodes of mice bearing transplantable OVA‐expressing murine sarcoma (MCA‐OVA), but CCR2‐deficient Treg cells failed to infiltrate the TME.14 Furthermore, CCR2‐deficient Treg cells resulted in reduced CD25 expression, rendering them less suppressive,15 suggesting an alternative non‐chemotactic role for CCR2 in Treg cells. CCR2 expression has also been positively correlated with increased expression of inhibitory cytokine interleukin‐10 (IL‐10) in Treg cells.16 These observations suggest that CCR2 may play a dual role in tissue‐infiltrating Treg cells by facilitating their migration to the inflammatory site and promoting their functional fitness to maintain tissue homeostasis.

The importance of the CCL2–CCR2 axis in tumor development and progression has been reported in various cancer types, such as clear‐cell renal cell carcinoma17 in which high CCL2 and/or CCR2 expression was strongly correlated with poor patient prognosis. These observations suggest that targeting CCR2 may be a practical therapeutic approach to prevent Treg cell infiltration and intrinsically impair their suppressive function in the TME (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical studies of cancer immunotherapy targeting markers associated with tumor‐infiltrating Treg cells

| Target molecule | Drug | Manufacturer | Description | Phases of trials actively recruiting | Types of cancer tested in clinical trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCR2 | BMS‐813160 | Bristol‐Myers Squibb | CCR2/5 small molecule inhibitor | Phase I, II | Metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC), pancreatic cancer |

| CCR4 | Mogamulizumab (KW‐0761) | Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Development | Monoclonal anti‐human CCR4 (afucosylated humanized IgG1) | Phase I, II | Metastatic triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC), gastric cancers, locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), relapsed or refractory non‐Hodgkin's (NHL), Hodgkin's (HL), diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas (DLBCL), esophageal squamous cell cancer, renal cell carcinoma (RCC), oral squamous cell carcinomas |

| CCR8 | No CCR8‐targeted agents are currently investigated in cancer immunotherapy clinical trial. | N/A | |||

| CTLA4 | Ipilimumab | Bristol‐Myers Squibb | Monoclonal anti‐human CTLA4 (human IgG1) | Phase I, II, III | Melanoma, salivary gland cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), brain and hepatic metastasis, DLBCL, bladder cancer, RCC, clear cell renal carcinoma (CCRCC), pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, CRC, NSCLC, TNBC, Merkel cell carcinoma, HCC, gastric, stomach, esophageal, gastroesophageal, gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) cancer, HL, NHL, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CML), and other advanced malignancies |

| Tremelimumab | MedImmune (Pfizer) | Monoclonal anti‐human CTLA4 (human IgG2) | Phase I, II, III | Melanoma, RCC, CCRCC, CRC, HCC, NSCLC, HNSCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma (CTCL), glioblastoma, breast cancers, germ cell tumor, non‐seminomatous germ cell tumor, seminoma, germinomatous germ cell tumor, dysgerminoma, pineal germ cell tumor, bladder cancer, thyroid cancer, and other advanced malignancies | |

| AGEN1884 | Agenus | Monoclonal anti‐human CTLA4 (human IgG1) | Phase I, II | Advanced NSCLC, cervical cancer, advanced solid tumors and lymphomas | |

| BCD‐145 | Biocad | Monoclonal anti‐human CTLA4 (IgG information unavailable) | Phase I | Melanoma | |

| REGN4659 | Regeneron Pharmaceuticals | Monoclonal anti‐human CTLA4 (human IgG1) | Phase I | NSCLC | |

| ADU‐1604 | Aduro Biotech | Monoclonal anti‐human CTLA4 (humanized IgG1) | Phase I | Metastatic melanoma | |

| CS1002 | CStone Pharmaceuticals | Monoclonal anti‐human CTLA4 (human IgG1) | Phase I | Therapy refractory metastatic solid tumors | |

| MGD019 | MacroGenics | Dual‐affinity re‐targeting (DART) anti‐CTLA4/PD1 bearing hinge‐stabilized human IgG4 Fc | Phase I | Unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors | |

| MEDI5752 | MedImmune | Bispecific monovalent anti‐CTLA4/PD1 (Fc‐engineered human IgG1) | Phase I | Advanced solid tumors | |

| PD1 | Pembrolizumab (MK‐3475, SCH 900475) | Merck Sharp & Dohme | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (human IgG4) | Phase I, II, III | Melanoma, TNBC, RCC, CRC, NSCLC, HNSCC, HCC, NHL, small‐cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), CTCL, peripheral T‐cell lymphoma (PTCL), Merkel cell carcinoma, breast cancers, glioblastoma, pancreatic cancer, mesothelioma, peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), and other advanced malignancies |

| Nivolumab (BMS‐936558, MDX‐1106, ONO‐4538) | Bristol‐Myers Squibb | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (human IgG4) | Phase I, II, III | Melanoma, brain metastasis, HCC, PTCL, HL, NHL, RCC, CCRCC, SCLC, NSCLC, HNSCC, MM, CLL, AML, CRC, DLBCL, bladder cancer, cervical, ovarian, primary peritoneal, Fallopian tube cancers, Merkel cell carcinoma, breast cancers, salivary gland cancer, urinary bladder cancer, biliary tract cancer, pancreatic cancer, thyroid cancer, and other advanced malignancies | |

| Camrelizumab (SHR‐1210) | Incyte Biosciences (Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine) | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (humanized IgG1) | Phase I, II, III | Melanoma, HL, NSCLC, CRC, gastric, esophageal, gastroesophageal cancers, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, biliary tract cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, cervical, ovarian, endometrial cancers, HCC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, breast cancer, primary mediastinal large B‐cell lymphoma, RCC, urothelial carcinoma | |

| Tislelizumab (BGB‐A317) | Celgene (BeiGene) | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (humanized IgG4) | Phase I, II, III | NSCLC, high‐level microsatellite instability (MSI‐H) or mismatch repair‐deficient (dMMR) solid tumors, locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors, gastric cancer, GEJ adenocarcinoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) | |

| BAT1306 | Bio‐Thera Solutions | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (humanized IgG information unavailable) | Phase II | MSI‐H/dMMR or high TMB CRC | |

| Toripalimab (JS001, TAB001) | Shanghai Junshi Biosciences | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (humanized IgG4) | Phase I, II, III | Gastric cancer, ESCC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, HNSCC, NSCLC, melanoma, RCC, HCC, neuroendocrine tumors, bladder urothelial carcinoma | |

| JTX‐4014 | Celgene (Jounce Therapeutics) | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (human IgG4) | Phase I | Histologically or cytologically confirmed extracranial solid malignancies | |

| Dostarlimab (TSR‐042) | Tesaro (AnaptysBi) | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (humanized IgG4) | Phase I, II, III | Ovarian cancer, NSCLC, endometrial cancers, MSI‐H solid tumors, advanced or metastatic solid tumors | |

| Cemiplimab‐rwlc (REGN2810) | Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (Sanofi) | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (human IgG4) | Phase I, II, III | Cervical cancer, advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, HL, NHL, NSCLC, prostate cancer, RCC, glioblastoma, HNSCC, basal cell carcinoma, plasma cell myeloma, and other advanced malignancies with no alternative therapeutic options | |

| Sintilimab (IBI308) | Eli Lilly (Innovent Biologics) | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (human IgG4) | Phase I, II, III | Gastric cancer, NSCLC, HCC, and other advanced solid malignancies | |

| RO7121661 | Roche | Bispecific anti‐TIM3/PD1 antibody | Phase I | Melanoma, NSCLC, advanced solid malignancies | |

| Cetrelimab (JNJ‐63723283) | Janssen Research & Development | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (human IgG4) | Phase I, II | Prostate cancer, urothelial carcinoma, SCLC, NSCLC, melanoma, RCC, bladder cancer, gastric, esophageal cancers, and high‐level MSI‐H/dMMR CRC, and other advanced solid malignancies | |

| INCMGA00012 (MGA012) | MacroGenics | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (human IgG4) | Phase I, II | Advanced solid malignancies | |

| AK105 | Akeso Biopharma | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (IgG information unavailable) | Phase I, II, III | HL, NSCLC, HNSCC, advanced solid malignancies | |

| HX008 | Taizhou Hanzhong Pharmaceuticals | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (human IgG information unavailable) | Phase II | dMMR or MSI‐H advanced solid malignancies | |

| SCT‐I10A | Sinocelltech | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (humanized IgG information unavailable) | Phase I | Advanced solid tumors or lymphomas | |

| HLX10 | Henlix Biotech | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (humanized IgG information unavailable) | Phase I | Advanced or metastatic malignancies refractory to standard therapy | |

| Sym021 | Symphogen | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (human IgG information unavailable) | Phase I | Locally metastatic malignancies that are refractory to available therapy | |

| Spartalizumab (PDR001) | Novartis | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (humanized IgG4) | Phase I, II | Melanoma, TNBC, NSCLC, RCC, pancreatic cancer, urothelial cancer, HNSCC, DLBCL, MSS‐CRC, HCC, endometrial cancer, MM, poorly‐differentiated gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma, ovarian cancer, AML | |

| Genolimzumab (GB226) | CBT Pharmaceutical | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (humanized IgG4) | Phase I, II | Alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS), RTCL, NHL | |

| CS1003 | CStone Pharmaceuticals | Monoclonal anti‐human PD1 (humanized IgG4) | Phase I | Refractory advanced or metastatic solid malignancies, unresectable lymphomas | |

| MGD019 | MacroGenics | Dual‐affinity re‐targeting (DART) anti‐CTLA4/PD1 bearing hinge‐stabilized human IgG4 Fc | Phase I | Unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic solid malignancies | |

| MEDI5752 | MedImmune | Bispecific monovalent anti‐CTLA4/PD1 (Fc‐engineered human IgG1) | Phase I | Advanced solid malignancies | |

| LAG3 | Sym022 | Symphogen | Monoclonal anti‐human LAG3 (recombinant human Fc‐inert) | Phase I | Lymphoma, metastatic solid malignancies |

| Relatlimab (BMS‐986016) | Bristol‐Myers Squibb | Monoclonal anti‐human LAG3 (human IgG4) | Phase I, II, III | Melanoma, CRC, MSS‐CRC, gastric, esophageal, gastroesophageal cancers, GEJ cancer, cervical, ovarian, bladder, cancer, HNSCC, HCC, NSCLC, RCC, CLL, HL, NHL, MM, DLBCL | |

| REGN3767 | Regeneron Pharmaceuticals | Monoclonal anti‐human LAG3 (human hinge‐stabilized IgG4) | Phase I | PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitor treatment‐naive malignancies | |

| TSR‐033 | Tesaro (AnaptysBi) | Monoclonal anti‐human LAG3 (humanized high affinity IgG4 kappa chain) | Phase I | Advanced, unresectable solid malignancies | |

| MGD013 | MacroGenics | Dual‐affinity re‐targeting (DART) anti‐PD1/LAG3 bearing human IgG4 Fc | Phase I | Advanced, unresectable solid tumors and hematological malignancies | |

| IMP321 | Immutep | Human LAG3‐Fc fusion protein | Phase I, II | Advanced estrogen receptor‐positive (ER+) and progesterone receptor‐positive (PR+) breast cancers, and other locally advanced or metastatic solid malignancies | |

| FS118 | F‐star | Bispecific anti‐LAG3/PDL1 antibody composed of anti‐human LAG3 binding Fc (Fcab) structurally incorporated into the Fc‐region of anti‐human PDL1 IgG1 monoclonal antibody | Phase I | Locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic malignancies that progressed on or after PD‐1/PD‐L1 containing therapy | |

| INCAGN02385 | Agenus (Incyte Corporation) | Monoclonal anti‐human LAG3 (Fc‐engineered immunoglobulin G1‐kappa (IgG1κ)) | Phase I | Melanoma, cervical cancer, MSI‐high endometrial cancer, gastric cancer, GEJ cancer, esophageal cancer, HCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, mesothelioma, MSI‐high CRC, SCLC, NSCLC, ovarian cancer, HNSCC, RCC, TNBC, urothelial carcinoma, DLBCL | |

| LAG525 (IMP701) | Novartis (Immutep) | Monoclonal anti‐human LAG3 (humanized IgG4) | Phase I, II | Advanced TNBC, melanoma | |

| MK4280 | Merck Sharp & Dohme | Monoclonal anti‐human LAG3 (humanized IgG4) | Phase I, II | Classical Hodgkin's lymphoma (CHL), DLBCL, indolent non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (iNHL), and other metastatic solid malignancies | |

| TIGIT | MK‐7684 | Merck Sharp & Dohme | Monoclonal anti‐human TIGIT (humanized IgG1) | Phase I | Advanced solid tumors, inoperable adenocarcinoma of stomach and/or GEJ cancers |

| AB154 | Arcus Biosciences | Monoclonal anti‐human TIGIT (humanized IgG1) | Phase I | Advanced malignancies, NSCLC, HNSCC, RCC, breast cancer, CRC, melanoma, bladder, ovarian, endometrial gastrointestinal cancers, Merkel cell carcinoma | |

| MTIG7192A | Genentech | Monoclonal anti‐human TIGIT (human IgG1) | Phase I | Advanced, metastatic malignancies, NSCLC | |

| BMS‐986207 | Bristol‐Myers Squibb | Monoclonal anti‐human TIGIT (human IgG1) | Phase I, II | Advanced solid malignancies | |

| ASP8374 (PTZ‐201) | Astellas Pharma (Potenza) | Monoclonal anti‐human TIGIT (human IgG4) | Phase I | Advanced solid malignancies | |

| TIM3 | Sym023 | Symphogen | Monoclonal anti‐human TIM3 (human) | Phase I | Refractory lymphomas, locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic solid malignancies, |

| Cobolimab (TSR‐022) | Tesaro (AnaptysBi) | Monoclonal anti‐human TIM3 (humanized IgG4) | Phase I | Metastatic solid malignancies, HCC, NSCLC | |

| RO7121661 | Roche | Bispecific anti‐TIM3/PD1 antibody | Phase I | Metastatic solid malignancies, melanoma, NSCLC | |

| LY3321367 | Eli Lilly | Monoclonal anti‐human TIM3 (human IgG1κ, Fc‐null) | Phase I | Advanced solid malignancies | |

| BGB‐A425 | BeiGene | Monoclonal anti‐human TIM3 (humanized IgG1) | Phase I, II | Locally advanced or unresectable, metastatic solid malignancies | |

| LY3415244 | Eli Lilly | Bispecific anti‐TIM3/PDL1 antibody | Phase I | Advanced solid malignancies | |

| INCAGN02390 | Agenus (Incyte Corporation) | Monoclonal anti‐human TIM3 (human IgG1, Fc‐silent) | Phase I | Cervical, gastric, stomach, GEJ, esophageal, ovarian cancers, melanoma, HCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, mesothelioma, SCLC, NSCLC, HNSCC, RCC, TNBC, urothelial carcinoma, MSI cancers | |

| MBG453 | Novartis | Monoclonal anti‐human TIM3 (human IgG4) | Phase I, II | Advanced or metastatic solid malignancies, AML | |

| BMS‐986258 | Bristol‐Myers Squibb | Monoclonal anti‐human TIM3 | Phase I, II | Advanced malignancies | |

| NRP1 | ASP1948 (PTZ‐329) | Astellas Pharma (Potenza) | Monoclonal anti‐human NRP1 (human IgG4) | Phase I | Advanced solid malignancies, NSCLC |

| TGF‐β | Galunisertib (LY2157299) | Eli Lilly | TGF‐βRI small molecule inhibitor | Phase I, II | CRC, uterine, ovarian, fallopian tube, peritoneal cancers, prostate cancer, rectal adenocarcinoma (Stage IIA‐IIIC or AJCC Stage IV), advanced (Stage IV) metastatic AR negative TNBC |

| M7824 (MSB0011359C) | Merck | Anti‐PDL1/TGF‐β TRAP bifunctional fusion protein composed of avelumab (anti‐PDL1) fused to soluble extracellular domain of human TGF‐βRII | Phase I, II | Breast cancer, NSCLC, HPV associated malignancies, anal, vulvar, vaginal, penile, squamous cell rectal and neuroendocrine cervical cancers, CRC, SCLC, TNBC, prostate cancer, locally advanced solid malignancies | |

| AVID200 | Forbius (Formation Biologics) | TGF‐β TRAP composed of TGF‐β receptor ectodomains fused to human Fc | Phase I | Any locally advanced or metastatic solid malignancies | |

| Fresolimumab (GC1008) | Cambridge Antibody Technology (Genzyme Corporation) | Pan‐specific monoclonal anti‐human TGF‐βRI, II, and III (fully human IgG4) | Phase I, II | Newly diagnosed early NSCLC | |

| LY3200882 | Eli Lilly | TGF‐β small molecule inhibitor | Phase I | Any solid malignancies | |

| PF‐06952229 | Pfizer | TGF‐βR1 inhibitor | Phase I | Metastatic and standard therapy‐resistant solid malignancies, breast cancer, prostate cancer | |

| IL‐10 | AM0010 | Merck | PEGylated recombinant human IL‐10 | Phase II, III | Metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, NSCLC |

| IL‐35 | No IL‐35‐targeted agents are currently investigated in cancer immunotherapy clinical trial | N/A | |||

Table represents a list of drugs found on ClinicalTrials.gov (as of February 2019) that are currently in clinical trials actively recruiting patients to investigate the safety and efficacy in various types of cancer as indicated. (Search terms: ‘CCR2’, ‘CCL2’, ‘CCR4’, ‘CCR8’, ‘CCL1’, ‘CTLA4’, ‘PD1’, ‘LAG3’, ‘TIGIT’, ‘TIM3’, ‘Neuropilin 1’, ‘NRP1’, ‘TGF’, ‘TGFβ’, ‘IL‐10’, ‘IL‐35’. There are no current clinical trials investigating drugs targeting CCL2, CCR8, CCL1, NRP1, and IL‐35.)

C‐C chemokine receptor 4

C‐C chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4) is a high‐affinity receptor for CCL17 and CCL22 that is elevated in inflamed tissues and plays a robust chemotactic role on activated T cells.18 Although only a small fraction of naive Treg cells express CCR4, activated effector Treg cells residing in non‐lymphoid tissues, such as skin and lungs, or peripheral activated effector Treg cells show enhanced expression of CCR4,19 suggesting that CCR4 plays a dual role in directing activated effector T cells while recruiting Treg cells to the site of inflammation to maintain immune homeostasis. Indeed, CCR4‐deficient Treg cells were unable to infiltrate localized tissue inflammation and failed to control immune responses in various models of inflammatory disease.13, 19

Consistent with these observations, infiltration of CCR4+ T cells in the TME has been reported in various types of cancer including lung adenocarcinoma20 in which increased CCR4+ tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) was correlated with poor patient prognosis,20 suggesting a pro‐tumor role of CCR4+ TILs. Administration of an afucosylated humanized anti‐CCR4 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Mogamulizumab; Table 1), which has enhanced capacity for antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity due to removal of N‐glucan attachment sites in the Fc region, in patients with NY‐ESO‐1‐positive adult T‐cell leukemia‐lymphoma selectively depleted CD4+ FOXP3hi CD45RA− activated Treg‐subset and subsequently increased interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ)/tumor necrosis factor‐α production by NY‐ESO‐1‐responsive CD8+ T cells.21 In addition, given that CCR4 is also highly up‐regulated on tumor cells,22 the mechanism underlying CCR4‐targeting clinical efficacy may be through dual‐depletion of CCR4+ tumor cells and CCR4+ TILs including Treg cells.

C‐C chemokine receptor 8

Early studies identified C‐C chemokine receptor 8 (CCR8) as a marker of CD4+ type 2 helper T (Th2) cells.23 However, CCR8 was later found to be expressed on human peripheral Treg cells, and its ligand CCL1 was able to induce their migration in vitro.24 CCR8‐deficient Treg cells showed increased susceptibility to cell death upon allogeneic adoptive transfer and were unable to prevent T cell‐induced graft‐versus‐host disease in lungs and colon,25 indicating an essential role of CCR8 in preserving long‐term fitness and functionality of Treg cells in non‐lymphoid organs. Indeed, recent studies have shown that intratumoral Treg cells or normal adjacent tissue‐resident Treg cells selectively up‐regulate CCR8 expression compared with their peripheral counterparts or other T‐cell subsets.26 In addition, the CCR8 expression within CD45+ intratumoral immune cells was almost exclusively on Treg cells in breast cancer;26 and the enrichment of CCR8 expression has been correlated with worse prognosis in patients with various types of cancer including breast cancer and melanoma.26

Interestingly, stimulation with its cognate ligand CCL1, but not other CCR8 ligands such as CCL8, CCL16 and CCL18, enhanced suppressive capacity of human Treg cells in vitro in a signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)‐dependent manner.27 Moreover, CCR8+ Treg cells up‐regulate CCL1 expression, thereby possibly promoting a positive paracrine feedback loop to sustain their suppressive potential in situ.27 Targeting CCR8+ Treg cells through either anti‐CCR8 mAb or anti‐CCL1 neutralizing mAb drastically reduced tumor‐infiltrating Treg cells while robustly enhancing the anti‐tumor immune response against murine tumor models such as colorectal adenocarcinoma.28 Although there are currently no known CCR8‐targeted therapeutics in clinical trials (Table 1), targeting CCR8 may be a highly selective therapeutic strategy sparing the peripheral Treg cells that do not express CCR8.

Inhibitory receptors

Inhibitory receptors (IRs), such as cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte‐associated protein 4 (CTLA4, CD152) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1, CD279), have been extensively investigated in the context of effector T‐cell exhaustion,29 but their impact on Treg cells is less well defined despite their up‐regulation in the TME.10 In this section, we review the impact of IRs on intratumoral Treg cells and their contribution to regulating anti‐tumor immunity (Fig. 1).

Cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte‐associated protein 4

Regulatory T cells constitutively express CTLA4 as its expression is controlled by Foxp3.1 Although CTLA4 is often retained intracellularly in circulating Treg cells, a subset of Treg cells up‐regulates surface CTLA4 expression in the TME.30 CTLA4 binds to and blocks CD80/CD86 with a significantly higher affinity than its co‐stimulatory counterpart CD28.10 Strikingly, CTLA4 can also physically remove CD80/CD86 from the surface of antigen‐presenting cells by trans‐endocytosis.31 In addition, dendritic cells up‐regulate indoleamine‐2,3‐dioxygenase (IDO) upon CTLA4‐binding and convert tryptophan to kynurenine in the local microenvironment.32 A recent study demonstrated that kynurenine induces T‐cell receptor (TCR)‐independent up‐regulation of PD1 in CD8+ TILs through activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor, leading to CD8+ T‐cell exhaustion.33 It is possible that Treg cells regulate anti‐tumor immune responses via a CTLA4–IDO–kynurenine axis.

Consistent with these observations, the enrichment of CTLA4+ TILs or Treg cells was associated with poor prognosis in patients with various types of cancer including non‐small cell lung cancer.34 Furthermore, the finding that administration of anti‐CTLA4 blocking antibody resulted in effective anti‐tumor immunity and protection against a secondary tumor challenge in murine cancer models35 led to the development of two mAbs against human CTLA4, ipilimumab (MDX‐010)36 and tremelimumab (CP‐675206)37 (Table 1). After successful clinical trials demonstrating an improved overall survival rate (20% after 4 years),38 ipilimumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma in 2011, with other CTLA4‐targeted therapeutics in clinical trials (Table 1). In addition, a recent study has shown that blocking CTLA4 on both effector T cells and Treg cells was required for maximal enhancement of anti‐tumor immunity.39 Hence, CTLA4 blockade not only inhibits CTLA4+ Treg‐mediated inhibition of T‐cell activation but it also improves effector T‐cell activity in a cell‐intrinsic manner.

Programmed cell death protein 1

Although effector T cells up‐regulate expression of PD1 upon TCR stimulation, PD1 is constitutively expressed on a small proportion of peripheral Treg cells,40 which is further up‐regulated in the TME.41 However, the cell‐intrinsic impact of PD1 expression on intratumoral Treg cells has not been fully elucidated. Despite the excitement around the success of anti‐PD1 checkpoint blockade for cancer immunotherapy [Nivolumab42 and Pembrolizumab,43 with many others in clinical trials (Table 1)], there remains a large proportion of patients who do not respond or who develop resistance overtime.44 It is therefore crucial to understand the potential impact of PD1 blockade on other intratumoral immune cells.

PD1 plays a crucial role in Treg cell homeostasis and survival as IL‐2 stimulation with PD1 blockade or genetic deletion of PD1 resulted in an overt proliferation of Treg cells followed by a rapid contraction due to increased apoptosis.40 A recent study reported that apoptotic intratumoral Treg cells express a low level of PD1 (PD1lo) whereas viable intratumoral Treg cells showed enhanced PD1 expression (PD1hi). Interestingly, apoptotic PD1lo Treg cells displayed superior suppressive capacity in an adenosine/A2A‐dependent manner through sustained expression of CD39 and CD73,45 indicating that PD1 expression on Treg cells may not positively correlate with their functionality. Consistently, PD1hi Treg cells isolated from blood or tumor of patients with glioblastoma multiforme have been characterized as a dysfunctional, effector T‐cell‐like population with inferior suppressive capacity.41 Further investigation is warranted to understand whether and how PD1hi and PD1lo Treg cells may be involved in the development of resistance to immunotherapy.

Lymphocyte‐activation gene 3

Lymphocyte‐activation gene 3 (LAG3), like other IRs, is transiently expressed on effector T cells upon TCR stimulation and cell‐intrinsically regulates proliferation and survival.46, 47 LAG3 is highly up‐regulated on exhausted CD8+ T cells,29 and increased expression of LAG3 on TILs has been associated with poor patient survival in various cancer types including non‐small cell lung cancer.48 Currently, there are at least 10 LAG3‐targeted therapeutics in clinical trials (Table 1).49 However, the impact of LAG3 blockade on LAG3+ intratumoral Treg cells has not been fully elucidated.

Unlike effector T cells, a subset of peripheral Treg cells constitutively expresses a low level of LAG3, which is further up‐regulated upon activation.47 LAG3+ Treg cells are highly enriched in the TME as well as in the circulation of individuals with cancer.50 Early studies have suggested that the expression of LAG3 is required for the maximal suppressive activity of Treg cells, as an antibody‐mediated blockade or genetic deletion of LAG3 severely impaired their function both in vitro and in vivo.46, 47 Moreover, recent studies demonstrated that human Treg cells isolated from individuals with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) showed enhanced suppressive function compared with Treg cells from matched patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells or healthy donors.50 Although the exact role of LAG3 on intratumoral Treg cells remains unclear, a recent study using a mouse model of autoimmune diabetes has shown that LAG3 intrinsically limits Treg cell function and survival, while LAG3‐deficient Treg cells substantially delayed the disease onset.51 Hence, it is possible that LAG3 blockade may limit or augment anti‐tumor immunity depending on the ratio of LAG3+ intratumoral Treg cells versus T effector cells as well as the severity of inflammation in the microenvironment.

T‐cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM domains

T‐cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM domains (TIGIT) is a recently discovered IR that belongs to the poliovirus receptor (PVR) family.52 The expression of TIGIT is highly restricted to the lymphocyte compartment, such as T cells and natural killer cells.53 Although TIGIT expression is up‐regulated upon TCR stimulation,52 a relatively large proportion of human Treg cells constitutively expresses TIGIT, which is further enhanced in the TME.53 TIGIT regulates effector T‐cell activation by competitively binding to its receptor PVR on antigen‐presenting cells with approximately 100‐fold higher affinity than its co‐stimulatory counterpart CD226.52 TIGIT can bind to both PVR and CD226, and prevention of CD226‐dimerization on the T‐cell surface is one of the key cell‐intrinsic regulatory mechanisms of TIGIT.52, 53 In addition, TIGIT is co‐expressed with PD1 on exhausted CD8 T cells,29 and TIGIT+ CD8+ T cells present a severely dysfunctional state with diminished cytokine production and proliferation.54, 55 Preclinical studies with Tigit −/− mice or anti‐TIGIT mAb treatment have been shown to greatly improve anti‐tumor immune responses in a CD8+ T‐cell‐dependent manner.54 Hence, TIGIT has been implicated as one of the potential cancer immunotherapeutic targets to elicit effective anti‐tumor immunity (Table 1).

However, recent studies have revealed previously unappreciated intrinsic roles of TIGIT in Treg cells. Despite previous observations that TIGIT expression marks a highly suppressive population of Treg cells,55, 56 the exact underlying mechanisms and the potential roles of intrinsic TIGIT‐signaling in Treg cells have not been fully elucidated. Whereas effector T cells up‐regulate both CD226 and TIGIT upon activation, Treg cells preferentially up‐regulate TIGIT over CD226.56 CD226‐signaling detrimentally impacts Treg cell stability and function, and TIGIT–PVR interaction was required to maintain the suppressive function of Treg cells.56 Furthermore, a recent study has demonstrated that TIGIT‐signaling repressed the PI3K‐Akt axis in an inositol polyphosphate‐5‐phosphatase D‐dependent manner leading to sustained nuclear localization of Foxo1, which was required to rescue Treg cells from an IFN‐γ‐secreting effector Th1‐like Treg phenotype induced by IL‐12 in a highly inflammatory environment, such as multiple sclerosis.57 These observations suggest that unlike LAG3, TIGIT is a selective IR that represses effector T‐cell function while enhancing Treg cell stability and function. Consistently, increased infiltration of TIGIT+ Treg cells has been correlated with poor prognosis of patients with melanoma.56 Interestingly, CD8+ T‐cell‐restricted TIGIT deletion did not improve anti‐tumor response in a Rag1 −/− adoptive transfer system,55 suggesting that preclinical efficacy observed with TIGIT blockade and Tigit −/− mice may have been due to functional destabilization of intratumoral Treg cells.

T‐cell immunoglobulin and mucin‐domain containing‐3

T‐cell immunoglobulin and mucin‐domain containing‐3 (TIM3) was first discovered and characterized as a marker for Th1 cells and type 1 cytotoxic CD8+ T cells.58 Interestingly, chronic T‐cell activation is required for sustained TIM3 expression on Th1‐polarized CD4+ T cells, implying a role for TIM3 during late‐stage T‐cell differentiation.58 TIM3 was subsequently characterized as one of the key markers associated with exhausted CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the context of both chronic viral infection59 and cancer.60 However, TIM3 lacks known inhibitory signaling motifs (ITIM or ITSM) around cytoplasmic tyrosine residues,59 so the TIM3‐signaling pathway has not been fully understood.

Similar to PD1, TIM3 is expressed by a small fraction of peripheral Treg cells, whereas a large proportion of intratumoral Treg cells express TIM3.50, 61 However, unlike PD1+/hi Treg cells, TIM3+ intratumoral Treg cells showed enhanced suppressive capacity due to increased expression of CTLA4 and CD39.50, 61 Increased infiltration of TIM3+ CD4+ T cells or TIM3+ Treg cells is associated with poor prognosis of patients with various malignancies including non‐small cell lung cancer.62 Given the preclinical observations that TIM3‐blocking mAbs could reinvigorate anti‐tumor immunity,63 several clinical trials are actively examining the safety and efficacy of TIM3 blockade therapy in both solid tumors and lymphomas (Table 1). However, as with PD1‐ and LAG3‐targeted therapies, further investigation of the impact of TIM3 on intratumoral Treg cells is warranted.

Markers for stability and enhanced function

Neuropilin 1

Neuropilin 1 (NRP1) is a type 1 transmembrane protein, first characterized as a receptor for a neural chemorepellent Semaphorin 3a (Sema3a).64 However, an early study demonstrated the role of NRP1 in priming T‐cell activation through a T cell–dendritic cell interaction‐dependent mechanism.65 Furthermore, NRP1 is constitutively expressed on murine Treg cells66 and has been defined as a discriminatory marker between thymically derived Treg cells and peripherally induced Treg cells.67, 68

Our recent study demonstrated that NRP1 expressed on the surface of murine Treg cells is constitutively associated with phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and Sema4a‐mediated NRP1 signaling is required to potentiate the immunoregulatory function of Treg cells by nuclear retention of Foxo3a through the PTEN–Akt axis at the immunological synapse (Fig. 1).69 Mice with a Treg‐restricted deletion of NRP1 exhibited an enhanced anti‐tumor response comparable to the Treg‐depletion model without succumbing to autoimmunity.69 These findings suggest that the NRP1–PTEN–Akt–Foxo3 axis is required for the functional stability of Treg cells in an inflammatory environment. Although conventional Treg instability is marked by a loss of Foxp3 expression,70 Treg cells with functional instability induced through the loss of NRP1 maintain the expression of Foxp3 while ectopically up‐regulating effector T‐cell‐like gene signature such as IFN‐γ;8, 69 hence, this unique state is referred to as Treg fragility.8 Strikingly, Treg fragility was required for the effective PD1‐blockade immunotherapy on established transplantable mouse adenocarcinoma (MC38) in an IFN‐γ‐dependent manner as Treg‐restricted deletion of IFN‐γR resulted in the diminished therapeutic efficacy of anti‐PD1 treatment.8

Unlike murine Treg cells, human Treg cells do not constitutively express NRP1. Instead, NRP1 is induced upon TCR stimulation, and perhaps other factors.71 Some studies have reported that a subset of Treg cells up‐regulate NRP1 expression in various types of cancer such as melanoma,8 consistent with the notion that the physiological role of NRP1 in Treg cells is restricted to inflammatory sites. In addition, increased infiltration of NRP1+ Treg cells in the TME has been associated with poor prognosis in patients with melanoma and HNSCC.8 Furthermore, tumor‐derived vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been shown to promote Treg cell infiltration into the TME in an NRP1‐dependent manner,72 suggesting a migratory role of NRP1 in Treg cells. The therapeutic targeting of NRP1 should provide insight into the impact of NRP1 blockade on the fragility and infiltration of human intratumoral Treg cells (Table 1).

Inhibitory cytokines

Secretion of inhibitory cytokines is one of the primary mechanisms used by Treg cells to regulate immune responses.2 Increased intratumoral expression of inhibitory cytokines is associated with poor prognosis in various cancer types.73, 74, 75 In this section, we discuss our current understanding of the role played by transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β +, IL‐10+ and IL‐35+ Treg subsets in the TME (Fig. 1).

Transforming growth factor‐β

Transforming growth factor‐β plays a pleiotropic role in the immune system and is also involved in thymic development of all T‐cell subsets. The absence of TGF‐β‐signaling results in defective thymic Treg cell development during the first 3–5 days of murine development.76 In addition, TGF‐β promotes the differentiation of induced Treg cells in vitro,2, 76 demonstrating its broad immunoregulatory functions in controlling inflammation. Furthermore, Treg‐derived TGF‐β plays a crucial role in regulating immune responses. Recent studies have reported the enriched presence of TGF‐β‐producing intratumoral Treg cells in various types of cancer, such as HNSCC,77 and their enhanced suppressive potential compared with peripheral Treg cells,78 indicating that TGF‐β is one of the major regulatory mechanisms that Treg cells employ in the TME. Indeed, elevated TGF‐β has been correlated with poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer79 and breast cancer.74 However, TGF‐β‐signaling blockade had no impact on intratumoral Treg cell accumulation or epigenetic status in a murine mammary gland tumor model.80 In addition, intratumoral effector T cells and Treg cells showed minimal TCR repertoire overlap,81 suggesting that thymically derived Treg cells may be the dominant intratumoral population and not intratumorally converted peripherally induced Treg cells.

These observations led to an increasing interest in targeting TGF‐β as a therapeutic approach (Table 1).82 For instance, a preclinical study using a mouse model of transplantable lung cancer (AG104Ld) demonstrated that blocking TGF‐β with a neutralizing mAb (clone A411) achieved tumor rejection comparable to transient Treg cell depletion with anti‐CD25 mAb (clone PC61) administration.83

In addition to its impact on the immune infiltrate, TGF‐β also directly supports tumorigenesis by promoting (i) angiogenesis in concert with VEGF, (ii) fibrosis and (iii) metastasis by promoting cancer cell motility and epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition.82 Further investigation is warranted to understand how many of these pro‐tumor factors are directly contributed by Treg‐derived TGF‐β in order to rationally design effective therapy against individual cancers that may present varying degrees of TGF‐β‐mediated pathophysiology in the TME.

Interleukin‐10

Interleukin‐10 was initially characterized as a Th1‐regulating factor produced by Th2 cells.84 Later studies demonstrated that its predominant suppressive mechanism is the regulation of the immunostimulatory potential of antigen‐presenting cells, resulting in impaired production of the pro‐inflammatory cytokine IL‐12, as well as expression of major histocompatibility complex class II and CD86.85, 86 Although many different cell types produce IL‐10,87 deletion in Treg cells was sufficient to induce spontaneous colitis,88 highlighting the physiological importance of Treg‐derived IL‐10. Although TCR stimulation is sufficient to induce the secretion of IL‐10 by Treg cells, co‐culturing in the presence of other immune cells, such as effector T cells, further enhanced the production of IL‐10 in vitro.89 A large proportion of intratumoral Treg cells show up‐regulation of IL‐10 in both humans and mice,90, 91 and in some tumor models, Treg cells are the predominant source of IL‐10.87 In addition, the enriched IL‐10 expression in the TME has been associated with poor prognosis in patients with HNSCC.75 We have recently demonstrated that intratumoral Treg‐derived IL‐10 directly modulates the BLIMP1 expression in CD8+ TILs, which in turn further promotes IR expression and T‐cell exhaustion.91 Treg‐restricted deletion of IL‐10 resulted in an altered myeloid compartment in the TME by upregulating T cell stimulatory molecules, such as major histocompatibility complex class II and CD80, on intratumoral dendritic cells, suggesting that Treg‐derived IL‐10 alters the TME, which can indirectly provide additional regulation of T‐cell‐mediated anti‐tumor immune responses.91

However, there has been increasing evidence that IL‐10 may also play an anti‐tumor role.92 For instance, early administration of IL‐10 impaired the dendritic cell vaccine‐mediated anti‐tumor response,93 consistent with the conventional inhibitory function of IL‐10. However, IL‐10 administration at a later time‐point, 7 days post‐vaccination, resulted in tumor regression as well as the expansion of antigen‐specific memory CD8+ T cells.93 Consistent with these observations, a recent study demonstrated that Treg‐derived IL‐10 was required during the resolution phase of inflammation to promote CD8+ T‐cell memory development by modulating the maturation status of dendritic cells.94 Furthermore, PEGylated IL‐10, which has enhanced in vivo stability, elicited increased activation of intratumoral CD8+ T cells with heightened IFN‐γ production, resulting in a remarkable rate of tumor regression and survival of mice with established large tumor burdens.95 However, given the enrichment of IL‐10+ Treg cells in progressively growing and established tumors,90 it appears that the outcome of anti‐tumor responses depends on the balance between immunostimulatory and immunoregulatory roles of Treg‐derived IL‐10. Further investigation is warranted to determine potential biomarkers that help to identify patients with cancer who may benefit from IL‐10 blockade or exogenous IL‐10 administration, especially given that PEGylated IL‐10 is in clinical trials (Table 1).

Interleukin‐35

Interleukin‐35 is a member of the IL‐12 cytokine family and is composed of p35 (encoded by Il12a) and Ebi3 (encoded by Ebi3).96 Although IL‐35 was initially reported to be preferentially expressed by activated Treg cells,97 two studies have shown that regulatory B cells can also express IL‐35.98, 99 The IL‐35 receptor (IL‐35R) on T cells consists of two shared subunits, IL‐12Rβ2 (encoded by Il12rb2) and gp130 (encoded by Il6st), which can be expressed as a heterodimer or homodimers of either chain. However, it has been suggested that the receptor on B cells may differ and consist of an IL‐12Rβ2 (encoded by Il12rb2)/WSX1 (encoded by Il27ra) heterodimer,98 highlighting the variability and promiscuity of the IL‐35R.96

Interestingly, the up‐regulation of IL‐35 expression in Treg cells required activation in the presence of cell–cell contact with effector T cells.89 This observation suggested that effector T cells provide positive feedback to enhance Treg cell functions, leading to the discovery of the NRP1–Sema4a axis69 as discussed above.

We have previously demonstrated that IL‐35+ Treg cells were highly enriched in the TME, comprising approximately 50% of intratumoral Treg cells in B16F10 tumor model7 and they promoted the expression of multiple IRs on CD4+ and CD8+ TILs.7 We have recently reported that one of the underlying mechanisms of Treg‐derived IL‐35‐mediated regulation of anti‐tumor responses was through direct modulation of BLIMP1 expression through IL‐35R‐signaling in CD8+ T cells, which in turn promoted IR expression and limited differentiation of central memory CD8+ T cells.91 Interestingly, Treg‐restricted single‐deletion of IL‐35 or double‐deletion of both IL‐10 and IL‐35 resulted in a comparable reduction of tumor burden and enhanced central memory T‐cell differentiation.91 These observations suggest that Treg‐derived IL‐35 may play a dominant immunoregulatory role over other inhibitory cytokines. Furthermore, enhanced expression of IL‐35 in the TME, by use of an IL‐35–B16F10 transfectant, accelerated tumor growth by enhancing the accumulation of myeloid‐derived suppressor cells and promoting angiogenesis.100 These observations indicate that Treg‐derived IL‐35 actively contributes to the immunosuppressive TME. There are currently no IL‐35‐targeted therapeutics in the clinic (Table 1), but systemic neutralization of IL‐35 has resulted in increased proliferation and inflammatory cytokine production by CD8+ TILs and reduced tumor growth in a preclinical murine tumor model.7 This may be a potent immunotherapeutic approach that promotes the anti‐tumor response of effector T cells while preventing IL‐35‐mediated pro‐tumor tissue remodeling.

Conclusion

Targeting immunoregulatory mechanisms, such as CTLA4 and PD1, have successfully provoked long‐term anti‐tumor immune responses in patients with advanced cancer, such as unresectable metastatic melanoma.38, 42, 43 This has led to an exponential growth of clinical trials investigating the efficacy of new cancer immunotherapies targeting additional immunoregulatory mechanisms. However, there remains a large proportion of cancer patients who do not benefit from checkpoint‐blockade cancer immunotherapy. Although these therapeutic approaches have been focused on the elicitation of inflammatory responses against cancer, enhanced inflammation could also play a detrimental role by facilitating the recruitment of Treg cells through chemokines such as CCL1 and CCL22, resulting in a dampening of the anti‐tumor responses. In addition, as demonstrated by the paradoxical functions of Treg‐derived IL‐10, the timing of therapeutic administration may also be critical.

Furthermore, although there is a largely overlapping list of effector molecules that Treg cells up‐regulate in the TME, intratumoral Treg cells may be highly heterogeneous, using distinct transcriptional programs to support their survival and functions. In addition, it is still unclear whether these Treg subsets represent distinct and stable lineages. For instance, intratumoral Treg cells seem to preferentially express IL‐10 or IL‐35, rarely both.91 It has been suggested that IL‐10+ or IL‐35+ Treg cells represent stable subsets,88 but we have found that the expression pattern of IL‐10 and IL‐35 can be altered upon TCR stimulation in vitro, indicating that this may instead represent transitional states of activated Treg cells in the TME.91 To effectively target intratumoral Treg cells, further investigation is warranted to fully understand the phenotypic and functional plasticity of Treg cell subsets that may potentially play a role in resistance to immunotherapy. Hence, to rationally design effective cancer immunotherapies, the next generation of cancer immunotherapies must consider: (i) appropriate combination of targets that augment effector responses, (ii) block Treg cell infiltration or function specifically in the TME, and (iii) determine the correct sequence of therapeutic administration to maximize beneficial impact, thereby also minimizing detrimental adverse effects.

Disclosures

The authors declare competing financial interests. DAAV and CJW have submitted patents covering LAG3 and IL‐35, and DAAV has submitted patents covering NRP1 that are pending or approved and are entitled to a share in net income generated from licensing of these patent rights for commercial development.

Acknowledgements

We thank Angela Gocher for comments. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01 CA203689 and P01 AI108545 to DAAV, and R01 AI144422 to CJW and DAAV.

References

- 1. Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science 2003; 299:1057–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8:523–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, Brunkow ME, Ferguson PJ, Whitesell L et al The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X‐linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet 2001; 27:20–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol 2007; 8:191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P et al Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med 2004; 10:942–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saito T, Nishikawa H, Wada H, Nagano Y, Sugiyama D, Atarashi K et al Two FOXP3+CD4+ T cell subpopulations distinctly control the prognosis of colorectal cancers. Nat Med 2016; 22:679–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turnis ME, Sawant DV, Szymczak‐Workman AL, Andrews LP, Delgoffe GM, Yano H et al Interleukin‐35 limits anti‐tumor immunity. Immunity 2016; 44:316–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Overacre‐Delgoffe AE, Chikina M, Dadey RE, Yano H, Brunazzi EA, Shayan G et al Interferon‐γ drives Treg fragility to promote anti‐tumor immunity. Cell 2017; 169:1130–1141.e1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salama P, Phillips M, Grieu F, Morris M, Zeps N, Joseph D et al Tumor‐infiltrating FOXP3+ T regulatory cells show strong prognostic significance in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:186–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tanaka A, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res 2017; 27:109–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, Shima T, Wing K, Niwa A et al Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity 2009; 30:899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11:762–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang N, Schröppel B, Lal G, Jakubzick C, Mao X, Chen D et al Regulatory T cells sequentially migrate from inflamed tissues to draining lymph nodes to suppress the alloimmune response. Immunity 2009; 30:458–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Loyher PL, Rochefort J, Baudesson de Chanville C, Hamon P, Lescaille G, Bertolus C et al CCR14 Influences T regulatory cell migration to tumors and serves as a biomarker of cyclophosphamide sensitivity. Cancer Res 2016; 76:6483–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhan Y, Wang N, Vasanthakumar A, Zhang Y, Chopin M, Nutt SL et al CCR2 enhances CD25 expression by FoxP3+ regulatory T cells and regulates their abundance independently of chemotaxis and CCR2+ myeloid cells. Cell Mol Immunol 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1038/s41423-018-0187-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feuerer M, Herrero L, Cipolletta D, Naaz A, Wong J, Nayer A et al Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nat Med 2009; 15:930–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Z, Xie H, Zhou L, Liu Z, Fu H, Zhu Y et al CCL2/CCR17 axis is associated with postoperative survival and recurrence of patients with non‐metastatic clear‐cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016; 7:51525–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scheu S, Ali S, Ruland C, Arolt V, Alferink J. The C‐C chemokines CCL17 and CCL22 and their receptor CCR18 in CNS autoimmunity. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18:2306–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sather BD, Treuting P, Perdue N, Miazgowicz M, Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY et al Altering the distribution of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells results in tissue‐specific inflammatory disease. J Exp Med 2007; 204:1335–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karasaki T, Qiang G, Anraku M, Sun Y, Shinozaki‐Ushiku A, Sato E et al High CCR20 expression in the tumor microenvironment is a poor prognostic indicator in lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Dis 2018; 10:4741–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sugiyama D, Nishikawa H, Maeda Y, Nishioka M, Tanemura A, Katayama I et al Anti‐CCR21 mAb selectively depletes effector‐type FoxP3+ CD4+ regulatory T cells, evoking antitumor immune responses in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110:17945–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kumai T, Nagato T, Kobayashi H, Komabayashi Y, Ueda S, Kishibe K et al CCL17 and CCL22/CCR22 signaling is a strong candidate for novel targeted therapy against nasal natural killer/T‐cell lymphoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2015; 64:697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zingoni A, Soto H, Hedrick JA, Stoppacciaro A, Storlazzi CT, Sinigaglia F et al The chemokine receptor CCR23 is preferentially expressed in Th2 but not Th1 cells. J Immunol 1998; 161:547–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iellem A, Mariani M, Lang R, Recalde H, Panina‐Bordignon P, Sinigaglia F et al Unique chemotactic response profile and specific expression of chemokine receptors CCR24 and CCR24 by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 2001; 194:847–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coghill JM, Fowler KA, West ML, Fulton LM, van Deventer H, McKinnon KP et al CC chemokine receptor 8 potentiates donor Treg survival and is critical for the prevention of murine graft‐versus‐host disease. Blood 2013; 122:825–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Plitas G, Konopacki C, Wu K, Bos PD, Morrow M, Putintseva EV et al Regulatory T cells exhibit distinct features in human breast cancer. Immunity 2016; 45:1122–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barsheshet Y, Wildbaum G, Levy E, Vitenshtein A, Akinseye C, Griggs J et al CCR27+ FOXp3+ Treg cells as master drivers of immune regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017; 114:6086–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Villarreal DO, L'Huillier A, Armington S, Mottershead C, Filippova EV, Coder BD et al Targeting CCR28 induces protective antitumor immunity and enhances vaccine‐induced responses in colon cancer. Cancer Res 2018; 78:5340–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15:486–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kwiecien I, Stelmaszczyk‐Emmel A, Polubiec‐Kownacka M, Dziedzic D, Domagala‐Kulawik J. Elevated regulatory T cells, surface and intracellular CTLA‐4 expression and interleukin‐17 in the lung cancer microenvironment in humans. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2017; 66:161–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qureshi OS, Zheng Y, Nakamura K, Attridge K, Manzotti C, Schmidt EM et al Trans‐endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: a molecular basis for the cell‐extrinsic function of CTLA‐4. Science 2011; 332:600–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grohmann U, Orabona C, Fallarino F, Vacca C, Calcinaro F, Falorni A et al CTLA‐4‐Ig regulates tryptophan catabolism in vivo . Nat Immunol 2002; 3:1097–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu Y, Liang X, Dong W, Fang Y, Lv J, Zhang T et al Tumor‐repopulating cells induce PD‐1 expression in CD8+ T cells by transferring kynurenine and AhR activation. Cancer Cell 2018; 33:480–494.e487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Paulsen EE, Kilvaer TK, Rakaee M, Richardsen E, Hald SM, Andersen S et al CTLA‐4 expression in the non‐small cell lung cancer patient tumor microenvironment: diverging prognostic impact in primary tumors and lymph node metastases. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2017; 66:1449–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA‐4 blockade. Science 1996; 271:1734–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Phan GQ, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Hwu P, Topalian SL, Schwartzentruber DJ et al Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte‐associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100:8372–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ribas A, Camacho LH, Lopez‐Berestein G, Pavlov D, Bulanhagui CA, Millham R et al Antitumor activity in melanoma and anti‐self responses in a phase I trial with the anti‐cytotoxic T lymphocyte‐associated antigen 4 monoclonal antibody CP‐675206. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:8968–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB et al Improved survival with Ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:711–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peggs KS, Quezada SA, Chambers CA, Korman AJ, Allison JP. Blockade of CTLA‐4 on both effector and regulatory T cell compartments contributes to the antitumor activity of anti‐CTLA‐4 antibodies. J Exp Med 2009; 206:1717–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Asano T, Meguri Y, Yoshioka T, Kishi Y, Iwamoto M, Nakamura M et al PD‐1 modulates regulatory T‐cell homeostasis during low‐dose interleukin‐2 therapy. Blood 2017; 129:2186–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lowther DE, Goods BA, Lucca LE, Lerner BA, Raddassi K, van Dijk D et al PD‐1 marks dysfunctional regulatory T cells in malignant gliomas. JCI Insight 2016; 1:e85935:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF et al Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti‐PD‐1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:2443–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R et al Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti‐PD‐1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:134–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bifulco CB, Urba WJ. Unmasking PD‐1 resistance by next‐generation sequencing. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:888–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Maj T, Wang W, Crespo J, Zhang H, Wang W, Wei S et al Oxidative stress controls regulatory T cell apoptosis and suppressor activity and PD‐L1‐blockade resistance in tumor. Nat Immunol 2017; 18:1332–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huang CT, Workman CJ, Flies D, Pan X, Marson AL, Zhou G et al Role of LAG‐3 in regulatory T cells. Immunity 2004; 21:503–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Workman CJ, Vignali DA. Negative regulation of T cell homeostasis by lymphocyte activation gene‐3 (CD223). J Immunol 2005; 174:688–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. He Y, Yu H, Rozeboom L, Rivard CJ, Ellison K, Dziadziuszko R et al LAG‐3 protein expression in non‐small cell lung cancer and its relationship with PD‐1/PD‐L1 and tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes. J Thorac Oncol 2017; 12:814–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Andrews LP, Marciscano AE, Drake CG, Vignali DA. LAG3 (CD223) as a cancer immunotherapy target. Immunol Rev 2017; 276:80–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jie HB, Gildener‐Leapman N, Li J, Srivastava RM, Gibson SP, Whiteside TL et al Intratumoral regulatory T cells upregulate immunosuppressive molecules in head and neck cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2013; 109:2629–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang Q, Chikina M, Szymczak‐Workman AL, Horne W, Kolls JK, Vignali KM et al LAG3 limits regulatory T cell proliferation and function in autoimmune diabetes. Sci Immunol 2017; 2:eaah4569:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yu X, Harden K, Gonzalez LC, Francesco M, Chiang E, Irving B et al The surface protein TIGIT suppresses T cell activation by promoting the generation of mature immunoregulatory dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 2009; 10:48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Johnston RJ, Comps‐Agrar L, Hackney J, Yu X, Huseni M, Yang Y et al The immunoreceptor TIGIT regulates antitumor and antiviral CD8+ T cell effector function. Cancer Cell 2014; 26:923–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Guillerey C, Harjunpää H, Carrié N, Kassem S, Teo T, Miles K et al TIGIT immune checkpoint blockade restores CD8+ T‐cell immunity against multiple myeloma. Blood 2018; 132:1689–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kurtulus S, Sakuishi K, Ngiow SF, Joller N, Tan DJ, Teng MW et al TIGIT predominantly regulates the immune response via regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest 2015; 125:4053–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56. Fourcade J, Sun Z, Chauvin JM, Ka M, Davar D, Pagliano O et al CD226 opposes TIGIT to disrupt Tregs in melanoma. JCI Insight 2018; 3:e121157:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lucca LE, Axisa PP, Singer ER, Nolan NM, Dominguez‐Villar M, Hafler DA. TIGIT signaling restores suppressor function of Th1 Tregs. JCI Insight 2019; 4:e124427:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Monney L, Sabatos CA, Gaglia JL, Ryu A, Waldner H, Chernova T et al Th1‐specific cell surface protein Tim‐3 regulates macrophage activation and severity of an autoimmune disease. Nature 2002; 415:536–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jones RB, Ndhlovu LC, Barbour JD, Sheth PM, Jha AR, Long BR et al Tim‐3 expression defines a novel population of dysfunctional T cells with highly elevated frequencies in progressive HIV‐1 infection. J Exp Med 2008; 205:2763–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sakuishi K, Apetoh L, Sullivan JM, Blazar BR, Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC. Targeting Tim‐3 and PD‐1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti‐tumor immunity. J Exp Med 2010; 207:2187–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Liu Z, McMichael EL, Shayan G, Li J, Chen K, Srivastava R et al Novel effector phenotype of Tim‐3+ regulatory T cells leads to enhanced suppressive function in head and neck cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2018; 24:4529–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Du W, Yang M, Turner A, Xu C, Ferris RL, Huang J et al TIM‐3 as a target for cancer immunotherapy and mechanisms of action. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18:645–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ngiow SF, von Scheidt B, Akiba H, Yagita H, Teng MW, Smyth MJ. Anti‐TIM3 antibody promotes T cell IFN‐γ‐mediated antitumor immunity and suppresses established tumors. Cancer Res 2011; 71:3540–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kawakami A, Kitsukawa T, Takagi S, Fujisawa H. Developmentally regulated expression of a cell surface protein, neuropilin, in the mouse nervous system. J Neurobiol 1996; 29:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tordjman R, Lepelletier Y, Lemarchandel V, Cambot M, Gaulard P, Hermine O et al A neuronal receptor, neuropilin‐1, is essential for the initiation of the primary immune response. Nat Immunol 2002; 3:477–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bruder D, Probst‐Kepper M, Westendorf AM, Geffers R, Beissert S, Loser K et al Neuropilin‐1: a surface marker of regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol 2004; 34:623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yadav M, Louvet C, Davini D, Gardner JM, Martinez‐Llordella M, Bailey‐Bucktrout S et al Neuropilin‐1 distinguishes natural and inducible regulatory T cells among regulatory T cell subsets in vivo . J Exp Med 2012; 209(1713–1722):s1711–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Abbas AK, Benoist C, Bluestone JA, Campbell DJ, Ghosh S, Hori S et al Regulatory T cells: recommendations to simplify the nomenclature. Nat Immunol 2013; 14:307–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Delgoffe GM, Woo SR, Turnis ME, Gravano DM, Guy C, Overacre AE et al Stability and function of regulatory T cells is maintained by a neuropilin‐1–semaphorin‐4a axis. Nature 2013; 501:252–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhou X, Bailey‐Bucktrout SL, Jeker LT, Penaranda C, Martínez‐Llordella M, Ashby M et al Instability of the transcription factor Foxp3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo . Nat Immunol 2009; 10:1000–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Milpied P, Renand A, Bruneau J, Mendes‐da‐Cruz DA, Jacquelin S, Asnafi V et al Neuropilin‐1 is not a marker of human Foxp3+ Treg. Eur J Immunol 2009; 39:1466–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hansen W. Neuropilin 1 guides regulatory T cells into VEGF‐producing melanoma. Oncoimmunology 2013; 2:e23039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhao Z, Chen X, Hao S, Jia R, Wang N, Chen S et al Increased interleukin‐35 expression in tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes correlates with poor prognosis in patients with breast cancer. Cytokine 2017; 89:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. de Kruijf EM, Dekker TJ, Hawinkels LJ, Putter H, Smit VT, Kroep JR et al The prognostic role of TGF‐β signaling pathway in breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2013; 24:384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bornstein S, Schmidt M, Choonoo G, Levin T, Gray J, Thomas CR Jr et al IL‐10 and integrin signaling pathways are associated with head and neck cancer progression. BMC Genom 2016; 17:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Li MO, Flavell RA. TGF‐β: a master of all T cell trades. Cell 2008; 134:392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Strauss L, Bergmann C, Szczepanski M, Gooding W, Johnson JT, Whiteside TL. A unique subset of CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ T cells secreting interleukin‐10 and transforming growth factor‐β1 mediates suppression in the tumor microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13:4345–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hilchey SP, De A, Rimsza LM, Bankert RB, Bernstein SH. Follicular lymphoma intratumoral CD4+ CD25+ GITR+ regulatory T cells potently suppress CD3/CD28‐costimulated autologous and allogeneic CD8+ CD25– and CD4+ CD25– T cells. J Immunol 2007; 178:4051–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Javle M, Li Y, Tan D, Dong X, Chang P, Kar S et al Biomarkers of TGF‐β signaling pathway and prognosis of pancreatic cancer. PLoS ONE 2014; 9:e85942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Waight JD, Takai S, Marelli B, Qin G, Hance KW, Zhang D et al Cutting edge: epigenetic regulation of Foxp3 defines a stable population of CD4+ regulatory T cells in tumors from mice and humans. J Immunol 2015; 194:878–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hindley JP, Ferreira C, Jones E, Lauder SN, Ladell K, Wynn KK et al Analysis of the T‐cell receptor repertoires of tumor‐infiltrating conventional and regulatory T cells reveals no evidence for conversion in carcinogen‐induced tumors. Cancer Res 2011; 71:736–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Neuzillet C, Tijeras‐Raballand A, Cohen R, Cros J, Faivre S, Raymond E et al Targeting the TGFβ pathway for cancer therapy. Pharmacol Ther 2015; 147:22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Yu P, Lee Y, Liu W, Krausz T, Chong A, Schreiber H et al Intratumor depletion of CD4+ cells unmasks tumor immunogenicity leading to the rejection of late‐stage tumors. J Exp Med 2005; 201:779–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Fiorentino DF, Bond MW, Mosmann TR. Two types of mouse T helper cell. IV. Th2 clones secrete a factor that inhibits cytokine production by Th1 clones. J Exp Med 1989; 170:2081–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. D'Andrea A, Aste‐Amezaga M, Valiante NM, Ma X, Kubin M, Trinchieri G. Interleukin 10 (IL‐10) inhibits human lymphocyte interferon gamma‐production by suppressing natural killer cell stimulatory factor/IL‐12 synthesis in accessory cells. J Exp Med 1993; 178:1041–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Buelens C, Willems F, Delvaux A, Piérard G, Delville JP, Velu T et al Interleukin‐10 differentially regulates B7‐1 (CD80) and B7‐2 (CD86) expression on human peripheral blood dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol 1995; 25:2668–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Stewart CA, Metheny H, Iida N, Smith L, Hanson M, Steinhagen F et al Interferon‐dependent IL‐10 production by Tregs limits tumor Th17 inflammation. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:4859–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Wei X, Zhang J, Gu Q, Huang M, Zhang W, Guo J et al Reciprocal expression of IL‐35 and IL‐10 defines two distinct effector Treg subsets that are required for maintenance of immune tolerance. Cell Rep 2017; 21:1853–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Collison LW, Pillai MR, Chaturvedi V, Vignali DA. Regulatory T cell suppression is potentiated by target T cells in a cell contact, IL‐35‐ and IL‐10‐dependent manner. J Immunol 2009; 182:6121–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Amedei A, Niccolai E, Benagiano M, Della Bella C, Cianchi F, Bechi P et al Ex vivo analysis of pancreatic cancer‐infiltrating T lymphocytes reveals that ENO‐specific Tregs accumulate in tumor tissue and inhibit Th1/Th17 effector cell functions. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2013; 62:1249–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sawant DV, Yano H, Chikina M, Zhang Q, Liao M, Liu C et al Adaptive plasticity of IL‐10+ and IL‐35+ Treg cells cooperatively promotes tumor T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol 2019; 20:724–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Mannino MH, Zhu Z, Xiao H, Bai Q, Wakefield MR, Fang Y. The paradoxical role of IL‐10 in immunity and cancer. Cancer Lett 2015; 367:103–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Fujii S, Shimizu K, Shimizu T, Lotze MT. Interleukin‐10 promotes the maintenance of antitumor CD8+ T‐cell effector function in situ . Blood 2001; 98:2143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Laidlaw BJ, Cui W, Amezquita RA, Gray SM, Guan T, Lu Y et al Production of IL‐10 by CD4+ regulatory T cells during the resolution of infection promotes the maturation of memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol 2015; 16:871–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Mumm JB, Emmerich J, Zhang X, Chan I, Wu L, Mauze S et al IL‐10 elicits IFNγ‐dependent tumor immune surveillance. Cancer Cell 2011; 20:781–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Vignali DA, Kuchroo VK. IL‐12 family cytokines: immunological playmakers. Nat Immunol 2012; 13:722–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Collison LW, Workman CJ, Kuo TT, Boyd K, Wang Y, Vignali KM et al The inhibitory cytokine IL‐35 contributes to regulatory T‐cell function. Nature 2007; 450:566–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wang RX, Yu CR, Dambuza IM, Mahdi RM, Dolinska MB, Sergeev YV et al Interleukin‐35 induces regulatory B cells that suppress autoimmune disease. Nat Med 2014; 20:633–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Shen P, Roch T, Lampropoulou V, O'Connor RA, Stervbo U, Hilgenberg E et al IL‐35‐producing B cells are critical regulators of immunity during autoimmune and infectious diseases. Nature 2014; 507:366–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wang Z, Liu JQ, Liu Z, Shen R, Zhang G, Xu J et al Tumor‐derived IL‐35 promotes tumor growth by enhancing myeloid cell accumulation and angiogenesis. J Immunol 2013; 190:2415–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]