Abstract

Liver transplantation is frequently associated with hyperkalemia, especially after graft reperfusion. Dual hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion (DHOPE) reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury and improves graft function, compared to conventional static cold storage (SCS). We examined the effect of DHOPE on ex situ and in vivo shifts of potassium and sodium. Potassium and sodium shifts were derived from balance measurements in a preclinical study of livers that underwent DHOPE (n = 6) or SCS alone (n = 9), followed by ex situ normothermic reperfusion. Similar measurements were performed in a clinical study of DHOPE‐preserved livers (n = 10) and control livers that were transplanted after SCS only (n = 9). During DHOPE, preclinical and clinical livers released a mean of 17 ± 2 and 34 ± 6 mmol potassium and took up 25 ± 9 and 24 ± 14 mmol sodium, respectively. After subsequent normothermic reperfusion, DHOPE‐preserved livers took up a mean of 19 ± 3 mmol potassium, while controls released 8 ± 5 mmol potassium. During liver transplantation, blood potassium levels decreased upon reperfusion of DHOPE‐preserved livers while levels increased after reperfusion of SCS‐preserved liver, delta potassium levels were ‐0.77 ± 0.20 vs. +0.64 ± 0.37 mmol/L, respectively (P = .002). While hyperkalemia is generally anticipated during transplantation of SCS‐preserved livers, reperfusion of hypothermic machine perfused livers can lead to decreased blood potassium or even hypokalemia in the recipient.

Keywords: donors and donation, liver transplantation/hepatology, organ perfusion and preservation, translational research/science

Short abstract

The authors examine the effect of hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion of donor livers on ex situ and in vivo potassium and sodium shifts and find that although hyperkalemia frequently occurs after reperfusion of a conventionally preserved liver, reperfusion of a hypothermic machine‐perfused liver leads to a decrease in blood potassium or even hypokalemia in the recipient.

Abbreviations

- DCD

donation after circulatory death

- DHOPE

dual hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion

- HMP

hypothermic machine perfusion

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MELD

model of end stage liver disease

- NMP

normothermic machine perfusion

- SCS

static cold storage

- UW

University of Wisconsin

1. INTRODUCTION

Liver transplantation is frequently accompanied by acute hyperkalemia during reperfusion, which may lead to life‐threatening arrhythmia. Several factors are known to contribute to hyperkalemia during liver transplantation, including the release of potassium rich preservation solution, cell lysis during graft reperfusion, metabolic acidosis, and massive transfusion of red blood cells.1, 2, 3, 4 To counteract an anticipated acute rise of potassium after graft reperfusion, anesthesiologists may take preventive measures, such as the administration of glucose/insulin, bicarbonate, calcium, or measures as hyperventilation.5, 6

Recently, end‐ischemic hypothermic (oxygenated) machine perfusion of donor livers has been introduced into clinical practice as a new method of organ preservation. Compared to SCS alone, additional graft preservation via hypothermic (oxygenated) machine perfusion reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury of liver grafts during transplantation.7, 8, 9 The perfusion fluid that is currently used in Europe and the US for hypothermic machine perfusion is Belzer's University of Wisconsin (UW) machine perfusion solution. Compared to UW cold storage solution, UW machine perfusion solution contains more sodium (100 mmol/L vs. 29 mmol/L) and less potassium (25 mmol/L vs. 125 mmol/L), although this is still much higher than the potassium concentration in serum. In our first clinical series of dual hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion (DHOPE) of donor livers we noted that, in contrast to SCS‐preserved livers, in vivo graft reperfusion did not result in acute hyperkalemia and in fact was accompanied by hypokalemia in three out of ten recipients.9 Little is known about cation (potassium and sodium) shifts in the liver during ex situ machine perfusion or during reperfusion in the recipient. As ex situ machine perfusion involves a closed circuit, this allows a direct calculation of cation uptake (influx) or release (efflux) by the liver.

The aim of the current study is to determine the effect of DHOPE on potassium and sodium shifts in human donor livers during machine perfusion and subsequent warm reperfusion in both a preclinical ex situ reperfusion model as well as in patients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

This study consisted of two parts: a preclinical study (part A) using human liver grafts that were declined for transplantation and a clinical study (part B) of patients who received a DHOPE‐preserved liver graft. In both preclinical and clinical study, DHOPE‐preserved liver grafts were compared with livers that were preserved with SCS alone (controls). The anonymized data analysis in both sub‐studies was performed in accordance with national guidelines and legislation. The preclinical study protocol was approved by the competent authority for organ donation in the Netherlands, the Dutch Transplantation Foundation (NTS) and by the medical ethical committee of our institution (University Medical Center Groningen, record METc protocol 2012.068). Ethical approval for the clinical study was obtained from the same medical ethical committee (record METc protocol 2014.100). In addition, the study protocol of the clinical study was published in an open access trial registry (www.trialregister.nl; trial ID NTR4493).

2.2. Organ procurement

All livers were procured according to a standard protocol by regional organ procurement teams, using a rapid flush out with ice‐cold UW cold storage solution (Bridge‐to‐Life, Ltd., Northbrook, IL) and subsequent SCS in the same fluid during transportation to our center. The potassium concentration of UW cold storage solution is 125 mmol/L, only slightly lower than the intracellular concentration (140 mmol/L).10 This minimizes the passive release of intracellular potassium into the extracellular milieu during SCS.11, 12 Likewise, the sodium concentration in UW cold storage solution is 29 mmol/L, only slightly above the intracellular concentration (10 mmol/L),10 minimizing influx of sodium.

During the back table procedure, livers were prepared for either machine perfusion in the preclinical (Part A) and clinical study (Part B), or for direct transplantation (controls in clinical study).

2.3. Dual hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion (DHOPE)

DHOPE was performed with 3 to 4L of UW machine perfusion solution (potassium concentration 25 mmol/L and sodium concentration 100 mmol/L; Bridge‐to‐Life, Ltd.) using the Liver Assist device (Organ Assist, Groningen, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Before the start of DHOPE, livers were flushed during the back table procedure with 1L of UW machine perfusion solution to flush out UW cold storage solution. The perfusion fluid was oxygenated to obtain a pO2 of approximately 80 kPa. During DHOPE, portal vein perfusion pressure was set at 4 mmHg and mean arterial perfusion pressure at 25 mmHg.

2.4. Part A: preclinical study

The preclinical study consisted of a total of 15 human donor livers that were declined for transplantation and offered to our center for research after informed consent had been obtained from the relatives of the donor. Livers were selected from a previous study based on the type of preservation fluid used during organ procurement.13 Only livers preserved in UW cold storage solution were included in the current study. Livers were divided into two groups: six livers underwent 2 hours of DHOPE prior to 6 hours of ex situ normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) to assess liver graft viability and function, and 9 livers underwent 6 hours of NMP without prior perfusion with DHOPE.

NMP was performed using the same Liver Assist device, using a solution based on packed red blood cells and plasma, as described previously.13, 14, 15 Prior to NMP, all livers were flushed with 1L cold NaCl 0.9% solution, followed by 500 mL warm NaCl 0.9% solution to flush out UW cold storage (control livers) or UW machine perfusion solution (DHOPE livers). Oxygenation resulted in a pO2 between 50 and 80k kPa. During NMP perfusion pressures were set at 11 mmHg for the portal vein and a mean of 70 mmHg for the hepatic artery.

2.5. Part B: clinical study

The clinical study included 10 patients undergoing liver transplantation, who received a liver that underwent 2 hours of DHOPE prior to implantation. Similar to the preclinical study, DHOPE was applied for 2 hours after conventional SCS. The control group consisted of nine patients who underwent transplantation without DHOPE treatment of the liver. They were matched for recipient age (±5 years), donor warm ischemia time (±5 minutes), and MELD score (6‐22 or ≥23). Livers were selected from a previously published clinical study.9 Only livers preserved in UW cold storage during the SCS phase were included.

All liver grafts were implanted by using the piggy back technique without veno‐venous bypass. Graft reperfusion was initiated by restoration of portal venous flow. To avoid hyperkalemia in the recipient, the first 400 mL of blood effluent from the liver was discarded before systemic venous return was established in both DHOPE and control livers. Subsequently the hepatic artery anastomosis was constructed and arterial blood flow to the liver was restored.

2.6. Assessment of cation concentrations and shifts

During machine perfusion (either DHOPE or NMP), perfusate samples were collected at baseline (prior to connecting liver) and every 30 minutes thereafter. During transplantation, blood samples of the recipient were collected from a nonheparinized arterial line: (a) prior to the anhepatic phase (pre‐anhepatic) and (b) during the anhepatic phase, and (c) after portal and (d) arterial reperfusion. Perfusate samples and blood samples were immediately processed for determination of potassium and sodium concentrations, using an ABL 800 point‐of‐care blood‐gas analyzer (Radiometer Medical ApS, Brønshøj, Denmark). Hypokalemia was defined as a potassium concentration <3.5 mmol/L and hyperkalemia as >5.0 mmol/L. All forms of potassium or sodium administration (eg, potassium chloride or sodium bicarbonate solution) during machine perfusion or during the transplant procedure were recorded.

The hepatic uptake (positive shift or influx) or release (negative shift or efflux) of potassium during ex situ machine perfusion was calculated according to the following formula:

where the expected delta in serum potassium concentration was defined as:

The observed rise or decrease in potassium concentration was defined as:

Here n and n + 1 denote two consecutive time points during machine perfusion and V stands for volume of the perfusion fluid. For calculating sodium shifts, similar formulae were used in which K+ was replaced by Na+.

2.7. Correlation between changes in cation levels and postreperfusion markers of hepatic viability and injury

In the preclinical study, changes in cation levels upon 'ex situ reperfusion’ (30 minutes after the start of NMP) were correlated with markers of hepatic viability (cellular ATP) and injury (peak perfusate levels of ALT and lactate). In the clinical study, changes in cation levels upon graft reperfusion were correlated with postoperative peak levels of serum ALT and lactate, and prothrombin time (PT) on postoperative day 1.

2.8. Correlation between changes in cation levels and postreperfusion syndrome

One of the more severe hemodynamic disturbances that can occur during liver transplantation is postreperfusion syndrome (PRS). PRS is defined as a drop in mean arterial pressure (MAP) of >30% of baseline values within 5 minutes after graft reperfusion that lasts for at least 1 minute.16 In the clinical study, changes in cation levels were correlated with changes in MAP and noradrenaline requirement after graft reperfusion.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as median with interquartile range (IQR), or as mean ± standard error (SE) as appropriate. Categorical variables are presented as number and percentage. Group characteristics were compared between groups using the Mann‐Whitney U‐test for continuous variables or the Chi‐square test for categorical variables. Strength and direction of association between two variables were determined by calculating the Spearman's correlation coefficient. Changes in cation levels were compared with a Student t‐test. A P value < .05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 23.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Part A: preclinical study

3.1.1. Donor characteristics

Donor and preservation characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups in donor characteristics such as donor age, type of donor, or donor warm ischemia time (in case of donation after circulatory death [DCD]).

Table 1.

Comparison of donor and preservation characteristics of livers in the preclinical study (Part A)

| DHOPE (n = 6) | Control (n = 9) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor characteristics | |||

| Age (y) | 64 (57‐70) | 62 (52‐64) | .29 |

| Sex (male) | 3 (50%) | 6 (67%) | .62 |

| Type of donor | .23 | ||

| DCD | 6 (100%) | 6 (67%) | |

| DBD | 0 | 3 (33%) | |

| Cause of death | .57 | ||

| Cardiovascular | 2 (33%) | 1 (11%) | |

| Post anoxic brain injury | 2 (33%) | 4 (44%) | |

| Trauma | 2 (33%) | 4 (44%) | |

| Reason rejected for transplantation | .35 | ||

| Age (DCD >60 y) | 5 (83%) | 4 (44%) | |

| Expected steatosis | 1 (17%) | 3 (33%) | |

| High transaminases | 0 | 1 (11%) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (11%) | |

| Preservation characteristics | |||

| Cold ischemia time (min)a | 489 (452‐513) | 509 (409‐660) | .72 |

| Time from withdrawal of life support to cold flushb (min) | 33 (26‐53) | 43 (38‐79) | .13 |

| Time from circulatory arrest to cold flushc (min) | 15 (13‐23) | 20 (16‐23) | .49 |

Data are presented as number (percentage) or median (interquartile range).

DCD, donation after circulatory death; DBD, donation after brain death.

Cold ischemia time was defined as the interval between start aortic cold flush in the donor until the start of NMP or DHOPE.

The time interval between the discontinuation of mechanical ventilation and the start of aortic cold flush in the donor (international donor warm ischemia time).

The time interval between cardiac arrest and the start of aortic cold flush in the donor.

3.1.2. Cation concentrations and shifts during end‐ischemic DHOPE

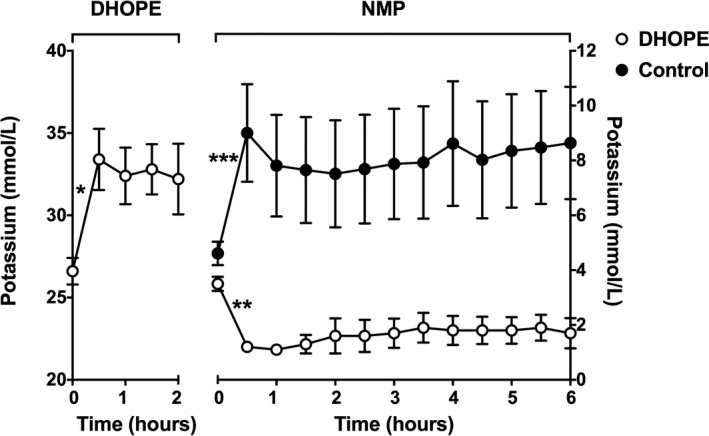

During the first 30 minutes of DHOPE, the mean perfusate potassium level increased from 26.6 ± 0.8 to 33.4 ± 1.9 mmol/L (P = .03) and levels remained stable thereafter (Figure 1). The total hepatic release of potassium during 2 hours of DHOPE was 17 ± 2 mmol.

Figure 1.

Mean potassium levels in perfusion fluid during DHOPE and NMP of preclinical livers. At baseline (time point zero), samples of the perfusion fluid were taken before the liver was connected to the perfusion device (Liver Assist). Potassium levels increased significantly during the first 30 minutes of DHOPE (*P = .03) and stabilized thereafter. During ex situ NMP of DHOPE‐preserved livers, potassium levels decreased significantly during the first 30 minutes (**P = .001) and stabilized thereafter. In contrast, during ex situ NMP of control livers, potassium levels increased significantly during the first 30 minutes (***P = .04) and stabilized thereafter. Note the different Y‐scales for DHOPE and NMP

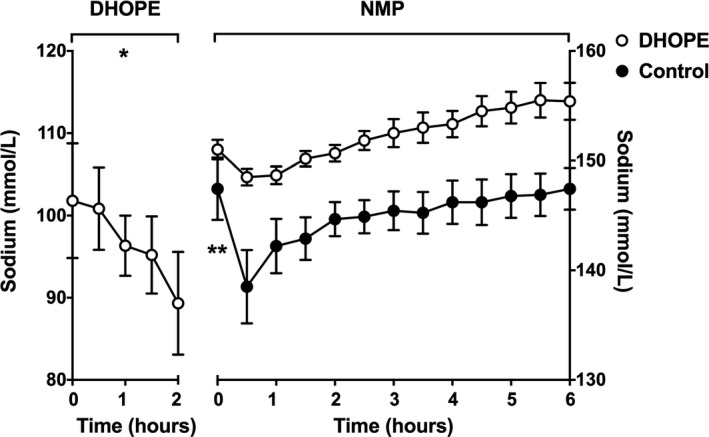

During the first 30 minutes of DHOPE, mean perfusate sodium level remained stable (102 ± 7 to 101 ± 6 mmol/L) (P = .91) but during the remainder of DHOPE, levels decreased from 102 ± 7 to 94 ± 6 mmol/L (P = .06) (Figure 2). The total hepatic uptake of sodium during 2 hours of DHOPE was 25 ± 9 mmol.

Figure 2.

Mean sodium levels in perfusion fluid during DHOPE and NMP of preclinical livers. At baseline (time point zero), samples of the perfusion fluid were taken before the liver was connected to the perfusion device (Liver Assist). Sodium levels remained stable during the first 30 minutes of DHOPE, but levels significantly decreased thereafter (*P = .06). During ex situ NMP of DHOPE‐preserved livers, no changes in sodium perfusate levels were observed in the first 30 minutes of NMP and levels remained to be stable thereafter. In contrast, during ex situ NMP of control livers, sodium levels significantly decreased during the first 30 minutes (**P = .02) and stabilized thereafter. Note the different Y‐scales for DHOPE and NMP

3.1.3. Cation concentrations, shifts and potassium‐related interventions during NMP

During NMP of the DHOPE‐preserved livers, potassium levels in the perfusion fluid decreased during the first 30 minutes from 3.5 ± 0.3 to 1.2 ± 0.1 mmol/L (P = .001). In livers that underwent NMP without prior DHOPE (controls), potassium levels increased during the first 30 minutes from 4.6 ± 0.4 to 9.0 ± 1.8 mmol/L (P = .04). Both groups showed stable perfusate potassium concentrations during the remainder of the NMP (Figure 1).

During NMP of DHOPE‐preserved livers, a total hepatic uptake of 19 ± 3 mmol of potassium was noted. In control (SCS alone) livers, an opposite potassium shift was observed with a total hepatic release of 8 ± 5 mmol. All DHOPE‐preserved livers required potassium supplementation during NMP to maintain potassium concentrations within an acceptable range, while in the control livers, only two (13%) needed potassium supplementation (P < .001).

During NMP of the DHOPE‐preserved livers, no changes in sodium perfusate levels were observed in the first 30 minutes of NMP (151 ± 1 to 149 ± 1 mmol/L, respectively; P = .78) and levels remained to be stable thereafter. In livers that underwent NMP without prior DHOPE (controls), sodium levels decreased during the first 30 minutes from 147 ± 3 to 139 ± 3 mmol/L (P = .02). Both groups showed stable perfusate sodium concentrations during the remainder of the NMP (Figure 2).

During NMP of DHOPE‐preserved livers, a total hepatic release of 7 ± 3 mmol of sodium was noted. In control (SCS alone) livers, an opposite sodium shift was noted with a total hepatic uptake of 23 ± 9 mmol of sodium.

3.1.4. Correlation between changes in cation levels and postreperfusion markers of hepatic viability and injury

After 2 hours of NMP, cellular ATP levels were significantly higher in DHOPE‐preserved livers compared to control livers, 88 (50‐137) μmol/g vs 36 (21‐57) μmol/g, respectively (P = .03). The change in potassium levels upon ex situ reperfusion correlated negatively with ATP levels after 2 hours of NMP (P < .001). In other words, an increase in potassium levels upon ex situ reperfusion correlated with low ATP levels (Table 2). In contrast, changes in sodium levels correlated positively with ATP levels after 2 hours of NMP (P = .048). Moreover, high potassium levels upon ex situ reperfusion strongly predicted high peak ALT levels (P < .001) and peak lactate levels (P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation between changes in cation levels and postreperfusion markers of hepatic viability and injury in the preclinical study

| Reperfusion levels | Δ Potassium (mmol/L) | Δ Sodium (mmol/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r s | P value | r s | P value | |

| Cellular ATP | −0.85 | <.001 | 0.58 | .048 |

| Peak ALT | 0.81 | <.001 | −0.61 | .02 |

| Peak lactate | 0.92 | <.001 | −0.72 | .008 |

Both DHOPE and control livers were included in a bivariate analysis to correlate changes in potassium and sodium levels upon "ex situ reperfusion" (30 minutes after the start of NMP) with levels of cellular energy marker ATP and perfusate peak levels of ALT and lactate. Data are presented as Spearman's correlation coefficient (r s).

ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; NMP, normothermic machine perfusion.

3.2. Part B: clinical study

3.2.1. Patient and donor characteristics

Patient, donor, and surgical characteristics are shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics or surgical variables between the groups. Most importantly, preoperative serum potassium and sodium concentrations, as well as intra‐operative blood loss and transfusion of packed red blood cells did not differ between the two groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of donor and recipient characteristics of transplanted livers (Part B)

| DHOPE (n = 10) | Control (n = 9) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor characteristics | |||

| Age (y) | 53 (47‐57) | 55 (50‐57) | .90 |

| Sex (male) | 5 (50%) | 5 (57%) | .46 |

| Type of donor | 1.00 | ||

| DCD | 10 (100%) | 9 (100%) | |

| DBD | 0 | 0 | |

| Cause of death | .73 | ||

| Cerebrovascular accident | 3 (30%) | 5 (56%) | |

| Post anoxic brain injury | 3 (30%) | 2 (22%) | |

| Trauma | 4 (40%) | 2 (22%) | |

| Recipient characteristics | |||

| Age (y) | 57 (54‐62) | 57 (53‐62) | .12 |

| Sex (male) | 6 (60%) | 4 (44%) | 1.00 |

| MELD score | 16 (15‐22) | 22 (17‐25) | .12 |

| Preservation characteristics | |||

| Cold ischemia time (min)a | 311 (282‐357) | 430 (424‐487) | <.001 |

| Time from withdrawal of life support to cold flush (min)b | 27 (23‐43) | 36 (29‐55) | .46 |

| Time from circulatory arrest to cold flush (min)c | 15 (13‐17) | 17 (15‐19) | .41 |

| Surgical variables | |||

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 3600 (1763‐4875) | 2700 (2200‐6600) | .91 |

| Preoperative serum [K+] (mmol/L) | 4.3 (4.1‐4.7) | 3.9 (3.9‐4.7) | .78 |

| Preoperative serum [Na+] (mmol/L) | 137 (133‐141) | 137 (134‐141) | .28 |

| RBC transfusion (unit) | 3 (1.5‐7.5) | 3 (0.5‐8.5) | .86 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or numbers (percentages).

DCD, donation after circulatory death, DBD, donation after brain death, MELD score, Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease score, RBC, Red Blood Cell.

Cold ischemia time was defined as the interval between start of aortic cold flush until start of DHOPE or in‐vivo graft reperfusion.

The time interval between the discontinuation of mechanical ventilation and the start of aortic cold flush in the donor (international donor warm ischemia time).

The time interval between cardiac arrest and the start of aortic cold flush in the donor.

3.2.2. Cation concentrations and shifts during end‐ischemic DHOPE

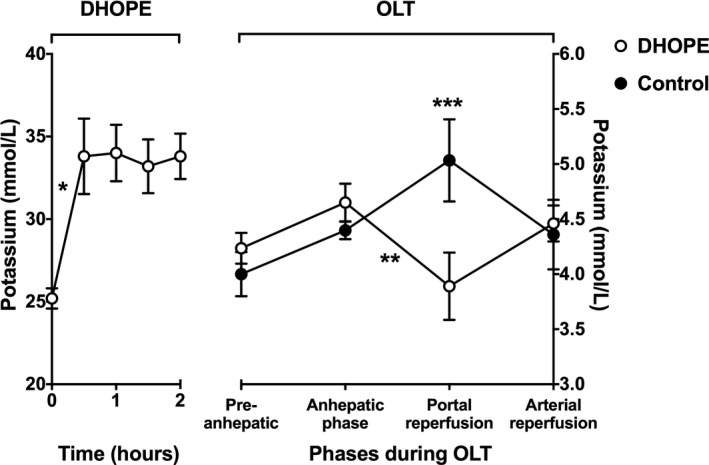

During the first 30 minutes of DHOPE, the potassium perfusate level increased from 25.2 ± 0.6 to 33.8 ± 2.3 mmol/L (P = .003), and levels remained stable thereafter (Figure 3). The total hepatic potassium release during 2 hours of DHOPE was 34 ± 6 mmol.

Figure 3.

Mean potassium levels in perfusion fluid during DHOPE and in recipient blood samples during subsequent orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). At baseline (time point zero), samples of the perfusion fluid were taken before the liver was connected to the perfusion device (Liver Assist). Potassium levels in the perfusion fluid increased significantly during the first 30 minutes of DHOPE (*P < .001), and stabilized thereafter. During OLT of DHOPE‐preserved livers, blood potassium levels decreased significantly after reperfusion (**P = .003). Moreover, at the time of graft reperfusion, blood potassium levels were significantly lower in DHOPE patients when compared to potassium levels at that time point in control patients (***P = .03). Note the different Y‐scales for DHOPE and NMP

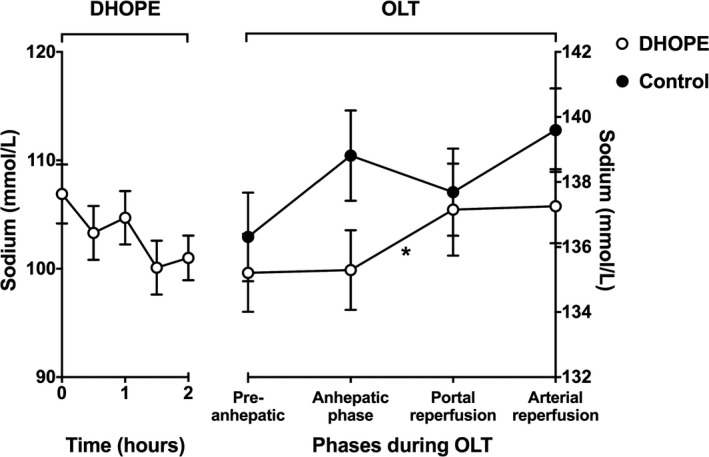

During the first 30 minutes of DHOPE, sodium levels slightly decreased from 107 ± 3 to 103 ± 2, yet this decrease did not reach significance (P = .22), and sodium levels remained stable thereafter (Figure 4). However, despite absence of a significant drop in sodium levels, the total (calculated) hepatic sodium uptake during 2 hours of DHOPE was still 24 ± 14 mmol.

Figure 4.

Mean sodium levels in perfusion fluid during DHOPE and in recipient blood samples during subsequent orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). At baseline (time point zero), samples of the perfusion fluid were taken before the liver was connected to the perfusion device (Liver Assist). Sodium levels in the perfusion fluid slightly decreased, during the first 30 minutes of DHOPE as well as during the remainder of DHOPE, yet not significantly. During OLT of DHOPE‐preserved livers, blood sodium levels increased significantly after reperfusion (*P = .04). During OLT of control livers, blood sodium levels slightly decreased after reperfusion, yet not significantly. Note the different Y‐scales for DHOPE and NMP

3.2.3. Cation concentrations during in vivo reperfusion and potassium‐related interventions

After in vivo graft reperfusion, blood potassium levels decreased from 4.7 ± 0.2 to 3.9 ± 0.3 mmol/L (P = .003) in recipients of a DHOPE‐preserved liver. In recipients of a control (SCS alone) liver, blood potassium levels increased from 4.4 ± 0.1 to 5.0 ± 0.4 mmol/L (P = .15; Figure 3). During OLT, three (30%) recipients of a DHOPE‐preserved liver required potassium supplementation, while no such supplementation was given to recipients of a control liver (P = .12).

After in vivo graft reperfusion, blood sodium levels slightly increased in recipients of a DHOPE‐treated liver (135 ± 1 to 137 ± 1 mmol/L, P = .04), whereas levels slightly decreased in control (SCS alone) recipients from 138 ± 2 to 137 ± 2 mmol/L, yet this did not reach significance (P = .23; Figure 4).

3.2.4. Correlation between changes in cation levels and postreperfusion markers of hepatic viability and injury

Increased potassium levels (mmol/L) upon portal reperfusion significantly correlated with higher peak serum ALT levels after transplantation (P = .001). There was no significant correlation between postreperfusion serum potassium levels and lactate levels and postoperative prothrombin times (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation between changes in cation levels and postreperfusion syndrome

| Reperfusion levels | Δ Potassium (mmol/L) | Δ Sodium (mmol/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r s | P value | r s | P value | |

| Peak ALT | 0.74 | .001 | −0.38 | .11 |

| Peak lactate | 0.29 | .27 | −0.27 | .26 |

| PT (POD 1) | 0.34 | .18 | −0.24 | .33 |

| Δ MAP | −0.23 | .40 | 0.25 | .33 |

| Δ Noradrenaline dose | 0.62 | .01 | −0.62 | .008 |

Both DHOPE and control livers were included in a bivariate analysis to correlate changes in potassium and sodium levels upon graft reperfusion with peak levels of ALT and lactate, and the PT value on postoperative day 1. Changes in cation levels were also correlated with changes in mean arterial pressure (Δ MAP) and changes in noradrenaline dose (Δ noradrenaline dose) upon reperfusion. Data are presented as Spearman's correlation coefficient (r s).

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PT, prothrombin time; POD, postoperative day.

3.2.5. Correlation between changes in cation levels and postreperfusion syndrome

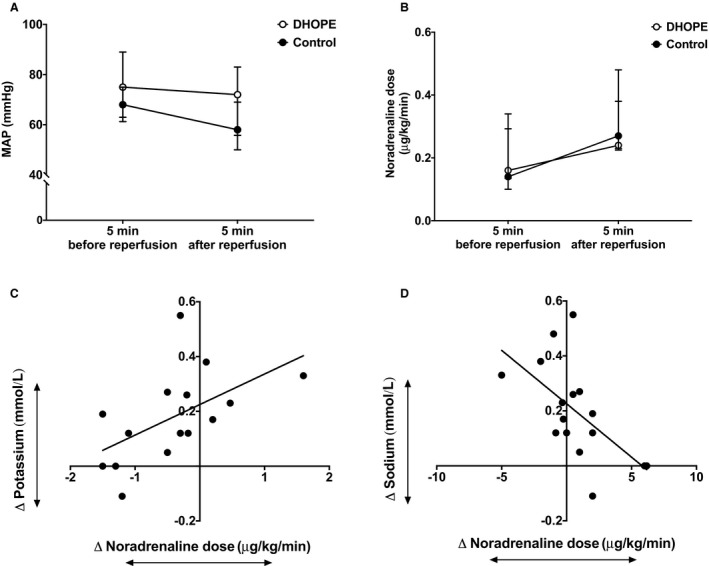

In vivo reperfusion of DHOPE‐preseved livers or control livers, resulted in minimal changes in median MAP (Figure 5). Postreperfusion syndrome occurred in zero out of 10 patients in the DHOPE group and in one out of seven in the control group (P = .44). Changes in MAP upon reperfusion did not correlate with changes in potassium and sodium levels (Table 4). Unfortunately, recordings of the MAP and noradrenaline dose around the time of reperfusion were missing in two (out of nine) patients in the control group.

Figure 5.

Changes in intraoperative hemodynamics upon reperfusion. No significant changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP) were noted after reperfusion of both DHOPE and control livers (A) while noradrenaline requirements increased in both groups (B). Increased noradrenaline dose upon reperfusion significantly correlated with increased potassium levels (C) and decreased sodium levels (D); P = .01 and P = 0.008, respectively

During in vivo reperfusion of DHOPE‐preserved livers, median noradrenaline requirement increased from 0.16 (0.14‐0.29) μg/kg/min to 0.24 (0.23‐0.48) μg/kg/min (P = .02). In controls, median noradrenaline requirement increased from 0.14 (0.14‐0.29) (μg/kg/min) to 0.27 (0.23‐0.38) (μg/kg/min) upon reperfusion, although did this not reach significance (P = .08) (Figure 5). Interestingly, increased potassium levels and decreased sodium levels upon reperfusion significantly correlated with increased noradrenaline requirement (Table 4).

4. DISCUSSION

In contrast to transplantation of conventional, SCS‐preserved livers, which is accompanied by a risk of acute hyperkalemia, transplantation of livers that underwent hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion was associated with a decrease in recipient blood potassium levels after graft reperfusion. These findings have clinical consequences for the perioperative management of liver transplant recipients as anesthesiologists and surgeons should anticipate a possible need for potassium administration to maintain normokalemia upon graft reperfusion of a liver graft that underwent hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion.

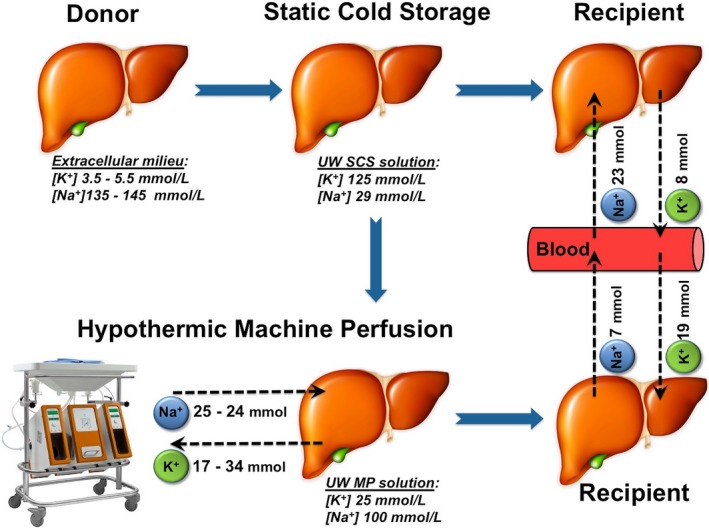

To our knowledge, this is the first study in which potassium and sodium shifts after reperfusion of DHOPE‐preserved livers were examined. We observed hepatic potassium release during DHOPE and hepatic potassium uptake after warm reperfusion of DHOPE‐preserved livers. Hepatic uptake of potassium upon warm reperfusion occurred both ex situ during NMP and in vivo during transplantation. In contrast, control livers that underwent only conventional SCS showed potassium release during warm reperfusion. Hepatic cation shifts during DHOPE and subsequent warm reperfusion or during SCS and warm reperfusion are summarized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Overview of potassium and sodium shifts during organ preservation and subsequent warm reperfusion. This cartoon summarizes cation shifts during hypothermic machine perfusion in both preclinical and clinical livers, and during subsequent warm reperfusion in the preclinical study. During static cold storage (SCS), donor livers were preserved in a high potassium and low sodium preservation solution, containing 125 mmol/L potassium and 29 mmol/L sodium. During warm reperfusion of SCS‐preserved livers, a mean total hepatic potassium release of 8 mmol and a mean total hepatic sodium uptake of 23 mmol was observed. During hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion, a mean total hepatic potassium release of 17 mmol in the preclinical and 34 mmol in the clinical study was noted. Simultaneously, a total hepatic sodium uptake of 25 mmol was noted during hypothermic machine perfusion in the preclinical study and of 24 mmol in the clinical study. Opposite cation shifts were observed during subsequent warm reperfusion of liver grafts. During reperfusion of DHOPE‐preserved livers, a total hepatic potassium uptake of 19 mmol and a total hepatic sodium release of 7 mmol was noted, whereas reperfusion of a SCS‐preserved livers was associated with a total hepatic release of 8 mmol potassium and a total hepatic uptake of 23 mmol of sodium. These differences in cation shifts explains the risk of a postreperfusion systemic hyperkalemia in recipients of a conventional SCS‐preserved liver and a decrease in blood potassium levels in recipients of a DHOPE‐preserved liver. UW, University of Wisconsin; SCS solution, static cold storage solution; MP solution, machine perfusion solution

Physiologically, the liver serves as a buffer for enteral potassium loads. Cellular potassium uptake requires active transport by the ATP‐dependent Na+/K+‐ATPase.4, 17 Low temperatures (8‐12 degrees Celsius) during DHOPE are likely to impair optimal function of Na+/K+‐ATPase, thereby facilitating passive potassium release.18 The total mean hepatic release of potassium during DHOPE varied from 17 mmol in preclinical livers to 34 mmol clinical livers (Figure 5). Also, as a consequence of impaired Na+/K+‐ATPase during DHOPE, the total mean hepatic sodium uptake was 25 to 29 mmol in preclinical and clinical livers, respectively. Moreover, in line with previously published data, cellular ATP levels were significantly higher in DHOPE preserved livers compared to controls upon ex situ reperfusion.13 Furthermore, this study showed that high ATP levels upon reperfusion significantly correlated with decreased potassium. This underlines the potential role of the ATP dependent hepatic potassium uptake in DHOPE‐preserved livers. Moreover, in both our preclinical and clinical study, increased potassium levels correlated with high peak ALT levels upon reperfusion. In other words, a decrease in potassium levels upon reperfusion might therefore be an interesting “early prediction” marker of good liver function. However, future studies are necessary to confirm this.

A decrease in blood potassium levels, as observed after reperfusion of DHOPE‐preserved liver grafts, is a remarkable and otherwise rarely observed phenomenon in patients undergoing liver transplantation. One previous study reported a slight decrease in potassium levels after reperfusion of UW‐preserved liver grafts compared to histidine‐tryptophan‐ketoglutarate solution in adult living donor liver transplantations.19 It must be noted that, due to logistical differences between postmortal and living donor liver transplantations, cold ischemia times (mean 66 minutes) in this study were substantially shorter than cold ischemia times in our study groups. In pediatric liver transplantation, hypokalemia after graft reperfusion is more commonly seen. The underlying mechanism has yet to be elucidated.20 Both living donor and pediatric liver transplant procedures can, however, not be compared with our patient group.

The first clinical series of oxygenated hypothermic machine perfusion did not report potassium or sodium concentrations.21 However, Guarrera et al published the first clinical series of transplantation of nonoxygenated hypothermic machine perfused (HMP) liver grafts.7 These authors used a perfusion solution with the same potassium content as Belzer‐UW machine perfusion solution (25 mmol/L). Changes in potassium levels during the first 30 minutes of HMP were not reported, but potassium levels were stable at approximately 30 mmol/L during the remainder of HMP. This level of potassium is comparable to the potassium levels in the perfusion fluid during DHOPE in our preclinical and clinical studies. Altogether, this suggests that similar shifts in potassium have occurred in the liver machine perfusions described by Guarrera et al, although the authors have not specifically noted this in their publication.7

While DHOPE and NMP constitute closed systems that are well suited to measure cation shifts, this was not possible during reperfusion in vivo. Nevertheless, the preclinical and clinical studies collectively point into the same direction and provide an explanation for the observed decrease in blood potassium levels in recipients of a DHOPE‐preserved liver.

As hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion, eg, DHOPE and HOPE, are entering the clinical arena as a method to reduce ischemia‐reperfusion injury in liver transplantation, it is of utmost importance that transplant anesthesiologists anticipate a decrease rather than an increase in blood potassium concentration after graft reperfusion. Current preemptive anti‐hyperkalemic measures, such as the use of glucose/insulin and sodium bicarbonate, might aggravate the decrease in blood potassium concentrations after reperfusion of DHOPE‐preserved livers. In our study, potassium supplementation was required more frequently during transplantation of a DHOPE‐preserved liver, compared to transplantation of a conventional SCS preserved liver. Modified perioperative management is thus appropriate during transplantation of a liver that underwent hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion.

Another clinical challenge that anesthesiologists may encounter during graft reperfusion is hemodynamic instability. While the exact pathophysiology of this postreperfusion syndrome (PRS) is not clearly understood, it has been correlated with high potassium levels and increased ischemia‐reperfusion injury.22 In this study we did not observe PRS in the DHOPE group. In the control group, one out of seven (14%) patients demonstrated PRS, which is in the lower range of the reported incidence of PRS during OLT (varying between 12% and 77%).23 In our study, median MAPs remained stable in both groups with adequate increase in the noradrenaline dose. We did, however, observe that increased noradrenaline requirements upon reperfusion correlated with increased potassium levels and decreased sodium levels. It has to be noted that data on MAP and inotropic doses were not complete in two out of nine control patients.

The decrease instead of increase in blood potassium concentration after reperfusion of a DHOPE‐preserved liver graft may actually be helpful in patients with concomitant renal insufficiency. Many patients with end‐stage liver disease also have some degree of renal failure, making them more prone for difficult to control hyperkalemia. The increase in blood potassium concentrations after reperfusion of a SCS‐preserved liver graft may cause cardiovascular instability due to arrhythmias in these patients and this problem should be less frequent after reperfusion of a DHOPE‐preserved liver.

In conclusion, while hyperkalemia is generally anticipated during transplantation of a SCS‐preserved liver, reperfusion of a DHOPE‐preserved liver is associated with potassium uptake by the liver, which can lead to a decrease in blood potassium concentrations or even hypokalemia. Anesthesiologists and surgical teams should be prepared for this opposite shift in potassium during transplantation.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Burlage LC, Hessels L, van Rijn R, et al. Opposite acute potassium and sodium shifts during transplantation of hypothermic machine perfused donor livers. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:1061–1071. 10.1111/ajt.15173

Laura C. Burlage and Lara Hessels contributed equally to this manuscript and are co‐first authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nakasuji M, Bookallil MJ. Pathophysiological mechanisms of postrevascularization hyperkalemia in orthotopic liver transplantation. Anesth Analg. 2000;91(6):1351‐1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Xia VW, Ghobrial RM, Du B, et al. Predictors of hyperkalemia in the prereperfusion, early postreperfusion, and late postreperfusion periods during adult liver transplantation. Anesth Analg. 2007;105(3):780‐785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen J, Singhapricha T, Memarzadeh M, et al. Storage age of transfused red blood cells during liver transplantation and its intraoperative and postoperative effects. World J Surg. 2012;36(10):2436‐2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carmicheal FJ, Lindop MJ, Farman JV. Anesthesia for hepatic transplantation: cardiovascular and metabolic alterations and their management. Anesth Analg. 1985;64(2):108‐116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Acosta F, Sansano T, Contreras RF, et al. Changes in serum potassium during reperfusion in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1999;31(6):2382‐2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Wolf A, Frenette L, Kang Y, et al. Insulin decreases the serum potassium concentration during the anhepatic stage of liver transplantation. Anesthesiology. 1993;78(4):677‐682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guarrera JV, Henry SD, Samstein B, et al. Hypothermic machine perfusion in human liver transplantation: the first clinical series. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(2):372‐381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dutkowski P, Polak WG, Muiesan P, et al. First comparison of hypothermic oxygenated perfusion versus static cold storage of human donation after cardiac death liver transplants: an international‐matched case analysis. Ann Surg. 2015;262(5):764‐770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Rijn R, Karimian N, Matton APM, et al. Dual hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion in liver transplantation with donation after circulatory death grafts. Brit J Surg. 2017;104(7):907‐917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hall EJ, Guyton CA. Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:45. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rose BD. Clinical Physiology of Acid‐Base and Electrolyte Disorders. New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill; 2001:346. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mangus RS, Tector AJ, Agarwal A, et al. Comparison of Histidine‐Tryptophan‐Ketoglutarate solution (HTK) and University of Wisconsin solution (UW) in adult liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(2):226‐230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Westerkamp AC, Karimian N, Matton APM, et al. Oxygenated hypothermic machine perfusion after static cold storage improves hepatobiliary function of extended criteria donor livers. Transplantation. 2016;100(4):825‐835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Op den Dries S, Karimian N, Porte RJ. Normothermic machine perfusion of discarded liver grafts. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(9):2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sutton ME, op den Dries S, Karimian N, et al. Criteria for viability assessment of discarded human donor livers during ex vivo normothermic machine perfusion. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e110642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aggarwal S, Kang Y, Freeman JA, et al. Postreperfusion syndrome: hypotension after reperfusion of the transplanted liver. J Crit Care. 1993;8(3):154‐160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shangraw RE. Metabolic issues in liver transplantation. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2006;44(3):1‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boutilier RG. Mechanisms of cell survival in hypoxia and hypothermia. J Exp Biol. 2001;204(18):3171‐3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Juang SE, Huang HW, Kao CW, et al. Effect of University of Wisconsin and histidine‐tryptophan‐ketoglutarate preservation solutions on blood potassium levels of patients undergoing living‐donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(2):366‐368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xia VW, Du B, Tran A, et al. Intraoperative hypokalemia in pediatric liver transplantation: incidence and risk factors. Anesth Analg. 2006;103(3):587‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dutkowski P, Schlegel A, de Oliveira M, et al. HOPE for human liver grafts obtained from donors after cardiac death. J Hepatol. 2014;60(4):765‐772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Angelico R, Perera MTPR, Ravikumar R, et al. Normothermic machine perfusion of deceased donor liver grafts is associated with improved postreperfusion hemodynamics. Transplant Direct. 2016;2(9):e97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Siniscalchi A, Gamberini L, Laici C, et al. Post reperfusion syndrome during liver transplantation: from pathophysiology to therapy and preventive strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(4):1551‐1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]