Abstract

Methods based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and photo-induced electron transfer (PET) are widely used in the biological sciences, employing mostly dye-based FRET and PET pairs. While very useful and important, dye-based reporters are not always applicable without concern, for example, in cases where the fluorophore size needs to be minimized. Therefore, development and characterization of smaller, ideally amino acid-based PET and FRET pairs will expand the biological spectroscopy toolbox to enable new applications. Herein, we show that, depending on the excitation wavelength, tryptophan and 4-cyanotrptophan can interact with each other via the mechanism of either energy or electron transfer, hence constituting a dual FRET and PET pair. The biological utility of this amino acid pair is further demonstrated by applying it to study the end-to-end collision rate of a short peptide, the mode of interaction between a ligand and BSA, and the activity of a protease.

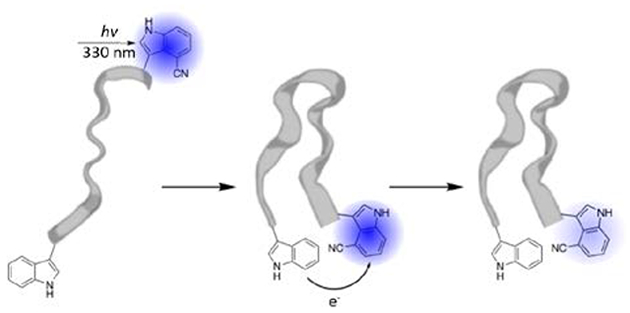

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Fluorescence emission is one of the most utilized physical properties in biological studies, enabling the assessment of a wide range of phenomena and problems. For example, it is especially useful to reveal information about the structure, dynamics, and interactions of biological molecules, both in vitro and in vivo, when the fluorescence signal of interest exhibits a dependence on a specific distance parameter. In this context, fluorescence intensity modulation based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)1–3 or photo-induced electron transfer (PET)4–6 is most widely exploited. The rate of FRET7 depends on 1/r6, where r is the separation distance between the fluorophore and modulator (i.e., acceptor in FRET and quencher in PET), whereas the rate of PET7 shows an exponential dependence on r. Therefore, in practice methods based on these two mechanisms are often used separately. As a result, the currently available fluorophore-modulator pairs are designed to perform a specific function, either FRET or PET. Hence, it would be quite useful to devise fluorophore-modulator pairs that can do both, as such pairs would provide not only convenience but also allow extraction of different types of information from a single fluorophore-modulator system. For example, when tracking a conformational motion that brings two initially separated sites to proximity, FRET can be used to monitor the early position of the trajectory, while PET is useful to provide information at later times when r becomes too short for FRET to capture any changes. Herein, we show that the unnatural amino acid (UAA) 4-cyanotryptophan (4CN-Trp) and endogenous tryptophan (Trp) constitute a dual FRET and PET pair.

In protein conformational studies, using an amino acid-based FRET or PET pair offers additional advantages, including (1) less perturbation to the native system,8 (2) ease of incorporation, and (3) site-specificity.9 In contrast, dye-based FRET and PET pairs are often bulky and more hydrophobic in comparison to amino acid sidechains and, therefore, likely to introduce adverse structural perturbations to the protein. For example, several recent studies showed that many commonly used fluorescent dyes could interact with each other, causing inaccurate results in protein conformational studies.10,11 Also, labeling a protein with two dyes through chemical reactions with amino acid sidechains could yield incomplete or unwanted products, hence leading to undesirable spectroscopic results.8,12

Recently, Hilaire et al.13 found that the absorption and emission spectra of 4CN-Trp (and its fluorophore 4CN-indole) are significantly red-shifted from those of Trp (and indole). As a result, the fluorescence spectrum of Trp exhibits a significant overlap with the absorption spectrum of 4CN-Trp. Therefore, it is apparent that Trp can be used as a FRET donor to 4CN-Trp. However, it is not obvious that Trp is also capable of modulating the fluorescence intensity of 4CN-Trp via the mechanism of PET. We hypothesize that this could occur based on the fact that Trp can effectively quench the fluorescence of oxazine- and rhodamine-based dyes through this mechanism.5,14,15 To validate this hypothesis, we carried out fluorescence titration experiments using free fluorophores as well as fluorescence intensity and lifetime measurements on a series of 4CN-Trp-containing peptides. Indeed, our results support the notion that Trp can quench the fluorescence of 4CN-Trp via PET and, by quantitatively analyzing the corresponding Stern-Volmer plot, we further determined the electron transfer rate constant, . Considering that 4CN-Trp is only a two-atom modification of Trp and that it has many desirable photophysical properties as a fluorescent UAA, such as high fluorescence quantum yield (QY) (>0.8), long fluorescence lifetime (13.7 ns), and good photostability,13,16 we expect that this amino acid pair will find various biological applications. For example, in three proof-of-principle studies, we demonstrated that it could be used to assess the end-to-end collision rate of peptides, protein-ligand interactions, and protease activity.

Experimental details

Sample preparation

Amino acids, N-acetyl-L-tryptophanamide (NATA), and 4-cyanoindole-3-acetic acid (4CNI-3AA) were purchased from Chem-Impex (Wood Dale, Il), Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and Ark Pharm (Arlington Heights, Il), respectively. All peptides were prepared by standard 9-fluorenylmethoxy-carbonyl (Fmoc) solid phase peptide synthesis method. Because the Fmoc protected 4-cyanotryptophan was not available commercially at the time of this study, the 4-cyanoindole fluorophore in all the peptides was introduced manually by coupling 4CNI-3AA to the N-terminus of the respective peptides through the formation of an amide bond. It has been shown that the photophysical property of the 4-cyanoindole fluorophore in such peptides, which only lacks the amino group at the N-terminus, is similar or identical to that of the 4-cyanoindole fluorophore in peptides made with 4-cyanotryptophan.13 Therefore, for convenience, all peptides were referred to as 4CN-Trp peptides. Each peptide was then purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography on an Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity (Santa Clara, CA) equipped with a Vydac C18 column (Berkshire, UK). The pH of the purified peptide solution was first titrated to ca. 7 using NaOH, and then the resultant peptide solution was lyophilized. The mass of each peptide was verified using either a liquid-chromatography mass spectrometer from Waters (Milford, MA) or a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometer from Bruker (Billerica, MA). All peptide samples used in the fluorescence measurements were prepared by dissolving the lyophilized peptide in Millipore water (pH 7). The peptide concentration (10 – 35 μM) was determined optically using the absorbance of the 4-cyanoindole fluorophore at 325 nm with ε = 4,750 M−1 cm−1.13

Static fluorescence measurement

All static fluorescence measurements were carried out on a Jobin Yvon Horiba Fluorolog 3.10 spectrofluorometer (Kyoto, Japan) at room temperature (unless indicated otherwise) using a 1 cm quartz cuvette, a 1.0 nm spectral resolution, and an integration time of 1.0 nm/s. The excitation wavelength for each measurement was either 270 or 330 nm, as indicated in the results section.

Time-resolved fluorescence measurements

Time-resolved fluorescence data were collected on a home-built time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) apparatus, the details of which have been described elsewhere.17 Briefly, a Ti:Sapphire oscillator (800 nm, 85.0 MHz) was used to derive the 270 nm excitation pulse through third harmonic generation while an electro-optical pulse picking system (Conoptics, Inc.) was used to reduce the repetition rate of the pulses to 21 MHz if necessary. To minimize any inner filter effect, the excitation beam was positioned near the edge of the 0.4 cm quartz sample cuvette that faces the fluorescence collection optics. Selection of the 4CN-Trp emission under magic angle polarization condition was achieved by passing the fluorescence beam through a long bandpass 300 nm filter (Semrock FF01–300) and a 403/95 nm bandpass filter (Semrock) or a 450 nm longpass filter (Semrock). Detection of the fluorescence signal was done with a MCP-PMT detector (Hamamatsu R2809U) and a TCSPC board (Becker and Hickl SPC-730). The fluorescence decays were deconvoluted with the experimental instrument response function (IRF) and were fit to either a single- or bi-exponential function using the FLUOFIT (Picoquant GmbH) program. All measurements were carried out at room temperature, and the fluorophore absorbance at 270 nm was in the range of 0.05 – 0.2. Details for Stern-Volmer titration and numerical fitting are in the SI.

Trypsin digest

The trypsin cleavage experiment was carried out at 37 °C, using 1 μM trypsin (Promega) to 15 μM peptide. Both samples were prepared in 50 mM tris buffer with 1 mM CaCl2 at pH 7.8. Fluorescence spectra of the mixture (λex = 330 nm) were measured at discrete reaction times, as indicated in the results section.

Results and discussion

FRET study

As indicated (Fig. 1), the fluorescence spectrum of Trp overlaps with the absorption spectrum of 4CN-Trp, indicating that the fluorescent state of Trp (4CN-Trp) can be de-excited (excited) via the mechanism of FRET. Based on standard practice (see detail in ESI), we determined the Förster distance (R0) of this FRET pair to be 24.6 Å. For an ideal FRET pair, the excitation light should only excite the donor fluorescence. While this is not the case for the Trp and Trp-4CN pair, using an excitation wavelength of 270 nm nevertheless allows almost selective excitation of Trp (the donor) as its absorbance at this wavelength is about 4 times higher than that of 4CN-Trp (Fig. S1, ESI). Similarly, for a PET pair, the excitation light should only populate the excited state(s) of the fluorophore, without exciting the quencher. As shown (Fig. 1), selective excitation of 4CN-Trp, when Trp is present, can be achieved by using an excitation wavelength in the range of 310 – 360 nm, wherein the absorbance of Trp is negligible.

Fig. 1.

Normalized absorption (blue) and fluorescence spectra (red) of Gly-Trp-Gly (dashed line) and 4CN-Trp-Gly (solid line) peptides in water. The excitation wavelength for the fluorescence measurements was 270 nm.

Amino acid sidechains that quench the fluorescence of 4CN-Trp

To show that Trp is the only amino acid that can significantly quench the fluorescence of 4CN-Trp, we studied the fluorescence property of a series of peptides with the sequence of 4CN-Trp-X (when X is a polar/charged residue) or 4CN-Trp-X-AAKKK (when X is a hydrophobic residue). In the latter case, the extra AAKKK segment is added to increase the peptide solubility. Specifically, the X residue represents one of the following amino acids: Gly, Met, His, Arg, Glu, Ser, Phe, Tyr, or Trp, and for simplicity, all these peptides are hereafter referred to as 4CN-Trp-X peptides, whose sequences are shown in Table S1 in ESI. As shown (Fig. 2), the fluorescence spectra of these peptides obtained under identical experimental conditions (e.g., concentration, temperature, and excitation wavelength) indeed indicate that only Trp, when in close proximity, can efficiently quench the fluorescence of 4CN-Trp. This conclusion is further corroborated by fluorescence lifetimes measurements (Fig. 3 and Fig. S2, ESI), which showed that the fluorescence decay of 4CN-Trp-Gly could be described by a single time constant of ca. 12.8 ns, close to the fluorescence lifetime of the free fluorophore,13 whereas that of 4CN-Trp-Trp not only is significantly faster but also requires a bi-exponential function to fit (Table 1). This deviation from single-exponential behavior is indicative of the existence of (at least) two peptide conformational ensembles that have distinctively different separation distances between the sidechains of Trp and 4CN-Trp (see below for further discussion). Additionally, since Trp has a negligible absorbance in the emission wavelength range of 4CN-Trp, this quenching effect cannot be attributed to FRET.

Fig. 2.

Fluorescence spectra of 4CN-Trp-X peptides in water (20 μM), as indicated. These spectra were collected under identical experimental conditions with an λex = 330 nm and, for easy comparison, their intensities have been scaled relative to that of 4CN-Trp-Gly.

Fig. 3.

Comparison between the fluorescence decay kinetics of 4CN-Trp-Gly and 4CN-Trp-Trp, as indicated. For 4CN-Trp-Gly, the decay curve can be fit by a single-exponential function, whereas that of 4CN-Trp-Trp requires a bi-exponential function to fit. The corresponding fitting parameters are listed n Table 1. Shown in the top panel are the residuals of the respective fits (smooth lines).

Table 1.

Fluorescence lifetime (τ) and relative amplitude (A%) determined from fitting the fluorescence decay kinetics of each peptide to a single or bi-exponential function. For each lifetime, the corresponding fluorophore-quencher separation distance (r) was calculated using Eq. (1).

| τ1 (ns) | A1 | r1 (Å) | τ2 (ns) | A2 | r2 (Å) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4CN-Trp-Gly | 12.8 | 100 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 4CN-Trp-Trp | 4.1 | 64 | 6.9 | 0.3 | 36 | 4.6 |

| 4CN-Trp-Pro-Trp | 6.4 | 62 | 7.5 | 1.2 | 38 | 5.7 |

| 4CN-Trp-Pro-Pro-Trp | 8.2 | 100 | 8.0 | --- | --- | --- |

| 4CN-Trp-(GS)4-Phe | 12.8 | 100 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 4CN-Trp-(GS)4-Trp | 5.7 | 100 | 7.3 | --- | --- | --- |

Stern-Volmer quenching measurements

Following common practice, we carried out further static fluorescence quenching experiments using a compound that contains the 4-cyanoindole fluorophore of 4CN-Trp, 4-cyanoindole-3-acetic acid (4CNI-3AA), and N-acetyl-L-tryptophanamide (NATA), in an attempt to determine the underlying quenching mechanism. As shown (Fig. 4), the resultant Stern-Volmer plot exhibits an upward curvature, indicative of a distance-dependent quenching process. A quantitative fitting of the Stern-Volmer curve using the diffusion model described in the literature7,18 and the numerical method detailed in the SI indicates that the following electron transfer rate equation7 can adequately describe the fluorescence quenching rate constant of NATA toward 4CN-Trp:

| (1) |

with k0 = 6.8 ns−1, β = 1.3 Å−1, and a0 = 7.0 Ẳ. Therefore, the Stern-Volmer quenching results support the notion that Trp quenches 4CN-Trp fluorescence via the mechanism of PET.

Fig. 4.

Relative fluorescence intensity of 4CNI-3AA (10 μM) as a function of the concentration of the quencher, NATA. These data were obtained with an λex = 330 nm and under the same fluorescence measurement conditions. Fitting these data to the model described in the text yielded the smooth line and the following parameters: k0 = 6.8 ns−1, β = 1.3 Å−1, and a0 = 7.0 Å.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Eq. (1) provides a direct means to determine the fluorophore-quencher separation distance (r) if the fluorescence decay lifetime of the fluorophore is known. For example, for the 4CN-Trp-Trp peptide, which exhibits bi-exponential fluorescence decay kinetics with time constants of 4.1 ns and 0.3 ns, respectively, the corresponding separation distances were calculated to be 6.9 and 4.6 Å (Table 1). To further substantiate this conclusion, we carried out molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to assess the conformational distribution of 4CN-Trp-Trp (see details in SI). As shown (Fig. 5), the calculated conformational distribution as a function of r, which corresponds to the edge-to-edge distance between the closest atoms on the sidechains of 4CN-Trp and Trp, consists of two peaks, at 6.3 (32%) and 2.9 Å (68%), respectively. These values are in agreement with those calculated via Eq. (1) and hence support its applicability.

Fig. 5.

Distribution of the separation distance between 4CN-Trp and Trp residues in 4CN-Trp-Trp peptide from MD simulations.

Quenching of 4CN-Trp fluorescence by Trp occurs at short distance

Eq. (1) indicates that efficient fluorescence quenching via PET can occur only when the fluorophore and quencher are at or near van der Waals contact.7 Therefore, to check whether the 4CN-Trp and Trp pair exhibits such characteristics, we studied another two peptides where the fluorophore and quencher are separated by either one or two proline residues, serving as a rigid spacer. As shown (Fig. 6), in comparison to that of 4CN-Trp-Trp, the fluorescence intensities of these proline-containing peptides are increased, with that of 4CN-Trp-Pro-Pro-Trp reaching to ca. 70% of the intensity of 4CN-Trp-Gly. The fluorescence decay kinetics (Table 1 and Fig. S3, ESI) are consistent with these results, which, taken together, confirm that efficient quenching of 4CN-Trp fluorescence by Trp occurs only when these two amino acids are close to each other.

Fig. 6.

Fluorescence spectra of different 4CN-Trp-containing peptides in water (20 μM), as indicated. These spectra were collected under identical experimental conditions with an λex = 330 nm and, for easy comparison, their intensities are scaled relative to that of 4CN-Trp-Gly.

Application to probe the loop formation rate of a short peptide

We believe that amino acid-based PET pairs, such as Trp and 4CN-Trp, will find various useful applications, especially in cases where using fluorescent dyes is prohibitive or undesirable. Below we describe three examples, demonstrating the biological utility of the Trp and 4CN-Trp pair. First, we employed it to probe the loop formation rate of a short peptide. Recently, Jacob et al.19 applied multiple techniques (e.g., FRET and PET) to assess the loop formation rate (kL) of a series of flexible and unstructured L1-(GS)n-L2 peptides, where L1 and L2 represent two different probes and n varies from 0 to 10. Their findings indicate that kL depends not only on n but also on the identity of L1 and L2, highlighting the importance of using non-interacting or weakly interacting probes in this type of experiments. In addition, their study provides valuable experimental data that can be used as a reference to validate the applicability of new PET and FRET pairs. Therefore, to make a direct comparison, we studied the 4CN-Trp-(GS)4-Trp peptide, which is an analogue of the Trp-(GS)4-MR121 peptide of Jacob et al.19

As shown (Fig. 7), compared to the fluorescence decay kinetics of a reference peptide that lacks the Trp quencher (sequence: 4CN-Trp-(GS)4-Phe), the fluorescence decay of 4CN-Trp-(GS)4-Trp is much faster, indicating that this peptide indeed samples an ensemble of dynamic conformations that can bring the terminal 4CN-Trp and Trp residues in close proximity for PET to occur. Specifically, the fluorescence lifetime of 4CN-Trp-(GS)4-Trp is 5.6 ns, comparing to the 12.8 ns of 4CN-Trp-(GS)4-Phe. Assuming that this change in the fluorescence lifetime of 4CN-Trp is only due to the addition of the PET quenching channel, the effective quenching rate constant (kQ) is calculated to be 9.9 × 107 s−1. As described by Jacob et al.,19 kQ is proportional to kL although the exact proportionality factor depends on the model used. Interestingly, the kQ value determined by Jacob et al.19 for Trp-(GS)4-MR121 is faster, ca. 1.7 × 108 s−1. We believe that this difference reflects the difference between 4CN-Trp and MR121, as the latter is larger and more hydrophobic. This notion is supported by previous studies showing that MR121 can preferentially interact with Trp and hence increases the loop formation rate.15,20 While 4CN-Trp and Trp will also likely show specific interactions, such as aromatic stacking, our result suggests that they are less perturbative to the native structure and dynamics of peptides, in comparison to commonly used hydrophobic dyes.

Fig. 7.

Fluorescence decay kinetics of 4CN-Trp-(GS)4-Phe and 4CN-Trp-(GS)4-Trp, as indicated. Fitting these kinetic traces to a single-exponential function yielded a decay time constant of 12.8 ns for 4CN-Trp-(GS)4-Phe and 5.6 ns for 4CN-Trp-(GS)4-Trp. Shown in the top panel are the corresponding residuals.

Application to probe ligand-protein binding interactions

In the second case, we demonstrate the utility of the Trp and 4CN-Trp pair in the context of biomolecular interactions using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a testbed. It is well known that BSA can interact with many small molecules21,22 through one of its two major binding sites (i.e., Sudlow’s site I and II). BSA contains two Trp residues, located at the 134 and 212 positions. However, based on its crystal structure,23 Trp134 is relatively far away from both binding sites. Therefore, Trp212, which is in the binding pocket of Sudlow’s site I, has been commonly used as a fluorescence reporter to assess small molecule binding.24 Similarly, this difference between sites I and II can be capitalized to determine the model of interaction of ligands that contain a 4CN-indole moiety (i.e., the fluorophore of 4CN-Trp) via fluorescence measurement. This is because only binding to site I can result in a significant quenching of the 4CN-indole fluorescence, due to PET. To test this notion, we studied the binding of 4CNI-3AA to BSA. We chose this molecule because it is a derivative of a known BSA-binding ligand, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA).25 As shown (Fig. 8A), in the presence of BSA the fluorescence spectrum of 4CNI-3AA (λex = 330 nm) does not show a significant decrease in intensity; instead, it is blue-shifted from that of the free 4CNI-3AA. This blue-shifted fluorescence spectrum of 4CNI-3AA suggests that in the presence of BSA the molecule samples a dehydrated or less-polar environment, as demonstrated by the study of Hilaire et al.16 Therefore, these data indicate that 4CNI-3AA is bound to BSA, but not within the binding pocket of Sudlow’s site I. This result is consistent with a previous study showing that IAA is bound to Sudlow’s site II of BSA.25

Fig. 8.

Fluorescence spectra of 4CNI-3AA (1 μM), BSA (100 μM), and the mixture of 4CNI-3AA (1 μM) and BSA (100 μM) obtained with an excitation wavelength of 330 nm (A) and 270 nm (B).

The fluorescence spectra obtained with λex = 270 nm provide further evidence supporting the abovementioned binding interaction between 4CNI-3AA and BSA. As indicated (Fig. 8B), in the presence of 4CNI-3AA the intrinsic fluorescence intensity of BSA (arising mostly from Trp and Tyr residues) is significantly decreased, accompanied by a significant increase in the fluorescence intensity of 4CNI-3AA. Together, these results indicate that the fluorescence of 4CNI-3AA is enhanced through a FRET mechanism, with Trp and/or Tyr residues being the FRET donors. Indeed, Trp212 is located at a position that is ca. 20 Å away from the center of Sudlow’s site II, which is well within the Förster distance (R0 = 24.6 Å) for efficient FRET to occur. Additionally, two Tyr residues, which are 7.8 Å and 11.5 Å away from the center of this binding site, could also contribute to the fluorescence enhancement of the reporter via FRET.

Application to probe protease activity

Finally, we show that 4CN-Trp and Trp can be used to assess protease activity. Proteases are responsible for activating proenzymes and degrading proteins, amongst other functions,26 hence playing a key role in many biological pathways. As such, various fluorogenic assays have been developed to detect their proteolytic activities.27 For in vitro studies, the available assays generally involve the use of short peptides labeled with two dyes, making them quite laborious to produce. Therefore, synthetic peptides containing a pair of 4CN-Trp and Trp would enjoy an advantage in this regard.

In a proof-of-principle study, we designed a peptide (sequence: 4CN-Trp-Lys-Trp-Ala-Gly-Lys) to measure the proteolytic activity of trypsin via fluorescence spectroscopy. Trypsin is a serine protease found in the digestive system of many organisms and used to break down proteins by hydrolyzing the amide bond at the C-terminal side of a Lys or Arg residue (not followed by a proline). The design of this peptide is based on the idea that the fluorescence intensity of 4CN-Trp is low in the intact peptide, due to Trp quenching, whereas after peptide cleavage by trypsin, which leads to the formation of 4CN-Trp-Lys and Trp-Ala-Gly-Lys fragments, the 4CN-Trp fluorescence intensity will significantly increase due to the removal of the PET quenching pathway. The experimental results obtained in the presence and absence of trypsin indeed show that upon peptide cleavage the fluorescence intensity of 4CN-Trp increases more than 6 times (Fig. 9), hence validating the utility of this amino acid PET pair in the study of protease function.

Fig. 9.

Fluorescence spectra of 4CN-Trp-Lys-Trp-Ala-Gly-Lys (15 μM) obtained before, 10 minutes, and 1 hour after the addition of 1 μM of trypsin (in 50 mM tris buffer, pH 7.8), as indicated. The excitation wavelength was 330 nm.

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrate that Trp can serve as either a FRET donor or a PET quencher to 4CN-Trp, a newly found blue fluorescent unnatural amino acid with a large fluorescence quantum yield (>0.8). The following considerations motivate this work: (1) spectroscopic techniques based on FRET and PET are widely used to assess protein conformations, conformational dynamics, and interactions; (2) evidence from several recent studies10,11 indicate that using dye-based fluorophores in FRET and PET applications can yield skewed results, due to specific or preferred probe-probe interactions. Therefore, development of amino acid-based FRET and PET pairs that are intrinsically less-perturbative and hence can minimize such pitfalls is needed; (3) the absorption spectrum of 4CN-Trp is significantly red-shifted from that of Trp, allowing selective excitation of its fluorescence (e.g., using λex = 330−360 nm) or that of Trp (e.g., using λex = 270 nm) in PET or FRET applications; (4) 4CN-Trp is only one atom larger than Trp, making it less perturbative to proteins than fluorescent dyes; (5) 4CN-Trp can now be conveniently synthesized via chemical28 and bilogical29 means; and (6) it is possible to incorporate 4CN-Trp into proteins genetically via amber codon suppression or chemically using a post-translational modification method.30,31 Given the unique photophysical property13,16,32 of 4CN-Trp and the less-perturbating nature of this unnatural amino acid and Trp, we believe that this pair will find valuable applications in biochemistry and biophysics, especially in cases where using dye-based PET or FRET reporters is deemed inappropriate. We are particularly excited about the possibility of using this pair of amino acids in single-molecule fluorescence studies, such as PET-FCS,6,33,34 as well as using it to study the functional and/or conformational dynamics of Trp-rich proteins.35

Supplementary Material

Highlight:

The amino acids tryptophan and 4-cyanotryptophan constitute a dual FRET and PET pair, useful for various biological applications.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (GM104605). I.A.A. is supported by NINDS D-SPAN Fellowship NIH (F99 NS108544–01), and C.M.E. acknowledges Penn’s Center for Undergraduate Research & Fellowships (PURM program) and Frances A. Velay Fellowship (Panaphil/Uphill Foundation).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic supplementary information

ESI contains the details for fluorescence Förster distance calculation, Stern-Volmer titration and fitting, MD simulation, as well as additional results.

REFERENCES

- 1.Förster T, Annalen der Physik, 1948, 2, 55–75.; English translation in: Mielczarek E. V., Greenbaum E. and Knox R. S., Editors. Biological Physics. American Institute of Physics; New York, USA, 1993, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Förster T, In: Sinanoglu O, Editor. Modern Quantum Chemistry. Academic Press Inc.; New York, USA, 1965, 93–137. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clegg RM, In: Wang XF and Herman B, Editors. Fluorescence Imaging Spectroscopy and Microscopy. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; New York, USA, 1996, 179–251. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seidel CA, Schulz A and Sauer MH, , J. Phys. Chem 1996, 100, 5541–5553. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuweiler H, Doose S and Sauer M, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A, 2005, 102, 16650–16655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doose S, Neuweiler H and Sauer M, ChemPhysChem, 2009, 10, 1389–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakowicz JR, Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Springer: New York, USA, 2nd edn. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waegele MM, Culik RM and Gai F, J. Phys. Chem. Lett, 2011, 2, 2598–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serrano AL, Bilsel O and Gai F, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2012, 116, 10631–10638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riback JA, Bowman MA, Zmyslowski A, Knoverek CR, Jumper J, Kaye E, Freed KF, Clark PL and Sosnick TR, Science, 2018, 361, 6405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riback JA, Bowman MA, Zmyslowski A, Plaxco KW, Clark PL and Sosnick TR, bioRxiv, 2018, 376632. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karolin J, Fa M, Wilczynska M, Ny T and Johansson LB, Biophys. J, 1998, 74, 11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilaire MR, Ahmed IA, Lin C, Jo H, DeGrado WF and Gai F, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A, 2017, 114, 6005–6009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neuweiler H, Schulz A, Bohmer M, Enderlein J and Sauer M, J. Am. Chem., Soc, 2003, 125, 5324–5330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuweiler H, Lollmann M, Doose S and Sauer M, J. Mol. Biol, 2007, 365, 856–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilaire MR, Mukherjee D, Troxler T and Gai F, Chem. Phys. Lett, 2017, 685, 133–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markiewicz BN, Mukherjee D, Troxler T and Gai F, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2016, 120, 936–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakowicz JR, Zelent B, Gryczynski I, Kuba J and Johnson ML, Photobiol, 1994, 60, 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacob MH, D’Souza RN, Schwarzlose T, Wang X, Huang F, Haas E and Nau WM, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2018, 122, 4445–4456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fierz B, Satzger H, Root C, Gilch P, Zinth W and Kiefhaber T, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S.A, 2007, 104, 2163–2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters TJ, Serum Albumin: Advances in Protein Chemistry. 1st edn. Academic Press; New York, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudlow G, Birkett DJ and Wade DN, Mol. Pharmacol, 1975, 11, 824–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majorek KA, Porebski PJ, Dayal A, Zimmerman MD, Jablonska K, Stewart AJ, Chruszcz M and Minor W, Mol. Immunol, 2012, 52, 174–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abou-Zied OK and Al-Shini OI, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2008, 130, 10793–10801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertuzzi A, Mingrone G, Gandolfi A, Greco AV, Ringoir S and Vanholder R, Clin. Chim. Acta, 1997, 265, 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.López-Otín C and Bond JS, J. Biol. Chem, 2008, 283, 30433–30437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong ILH and Yang KL, Analyst, 2017, 142, 1867–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang K, Ahmed IA, Kratochvil HT, DeGrado WF, Gai F and Jo H, Chem. Commun, 2019. (Advance Article, DOI: 10.1039/C9CC01152H). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boville CE, Romney DK, Almhjell PJ, Sieben M and Arnold FH, J. Org. Chem, 2018, 83, 7447–7452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed IA and Gai F, Protein Sci, 2017, 26, 375–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright TH, Bower BJ, Chalker JM, Bernardes GJ, Wiewiora R, Ng WL, Raj R, Faulkner S, Vallée MR, Phanumartwiwath A, Coleman OD, Thézénas ML, Khan M, Galan SR, Lercher L, Schombs MW, Gerstberger S, Palm-Espling ME, Baldwin AJ, Kessler BM, Claridge TD, Mohammed S and Davis BJ, Science, 2016, 354, 6312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed IA, Acharyya A, Eng CM, Rodgers JM, DeGrado WF, Jo H and Gai F, Molecules, 2019, 24, 602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Q and Seeger S, Anal. Chem, 2006, 78, 2732–2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin CW, Mensa B, Barniol-Xicota M, DeGrado WF and Gai F, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl, 2017, 56, 5283–5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Z, Li X, Zhong FW, Li J, Wang L, Shi Y and Zhong D, J. Phys. Chem. Lett, 2014, 5, 69–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.