Abstract

Background

Clinical experience suggests that childhood nephrotic syndrome is frequently diagnosed incorrectly, leading to delays in providing effective treatment. We hypothesized that the health care setting is an important determinant of diagnostic success, with implications for the patient and family health care experience. Our objectives were: (1) to characterize the relationship between diagnostic success and health care setting for the diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome, (2) to determine types and frequencies of incorrect diagnoses, and (3) to understand the burden placed on patients and families as a result of incorrect and incomplete diagnoses.

Methods

A survey was conducted by phone or in-person with legal guardians of children 1 to 18 years diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome within 24 months before the study. The survey elicited information on type of health care setting utilized (e.g., family practice, emergency room) and on diagnoses and treatments.

Results

Seventy-four patients with varying ethnicities and socioeconomic profiles (37 male, 37 female, median age 4.8 years, range: 1.2 to 14.8) were included from four Canadian paediatric nephrology centres. Proportions of diagnostic success were high in emergency and paediatric care settings (66% and 64% correct, respectively), but low in primary care settings (17% family practice and 17% walk-in clinic, respectively). Diagnostic delays ranged from 0 to 428 days (median 9.5, interquartile range [IQR] = 20.5). “Allergies” was the most common incorrect diagnosis (47%). Parents and legal guardians reported missed work (55%) and added expenses (50%) prior to obtaining a correct diagnosis.

Conclusions

Childhood nephrotic syndrome is often incorrectly diagnosed, especially in primary care settings.

Keywords: Nephrotic syndrome, Rare disease, Diagnostic delay, Patient experience

Nephrotic syndrome is an acquired kidney disease in children, with a prevalence of 16 per 100,000 in the population and an incidence of 2 to 7 per 100,000 children (1). It is characterized by an increase in glomerular permeability resulting in massive proteinuria (1–5), and is a relapsing remitting disease in >90% of affected individuals. This typically leads to recurring hypoalbuminemia and edema, predominantly around the eyelids, extremities, abdomen, and genital areas in children (2,3,5).

Prior to presentation to nephrology, primary care for children is usually provided by family doctors, walk-in clinics and, in some cases, emergency departments. The clinical experiences in paediatric nephrology centres suggest that many cases of nephrotic syndrome are initially incorrectly diagnosed as other common illnesses and conditions, such as allergies (5). Incorrect diagnoses may affect the treatments provided, health care costs, and patient and family experience. We hypothesized that the health care setting (e.g., emergency room, family medicine) is an important determinant of initial nephrotic syndrome diagnostic success.

Therefore, the objectives of our study were to characterize the relationship between diagnostic success and health care setting for diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome, to determine types and frequencies of incorrect diagnoses, and to understand the burden placed on patients and families as a result of incorrect and incomplete diagnoses.

METHODS

Study design and participant eligibility

We conducted a cross-sectional telephone survey among children enrolled in the Canadian Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome Project (CHILDNEPH), an ongoing prospective, observational study of children diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome. To be eligible for the CHILDNEPH study: patients must have been between the ages of 1 and 18 years, exhibit nephrotic syndrome diagnostic criteria (edema, hypoalbuminemia [albumin <25 g/L], nephrotic range proteinuria), and have no apparent secondary cause of nephrotic syndrome (6). Eligibility for the CHILDNEPH study was assessed during the first presentation, first relapse or second relapse of nephrotic syndrome. Patients were determined to be eligible for the survey study if (1) they previously gave consent for CHILDNEPH, (2) they were diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome no more than 24 months prior to date of completion of the survey, in order to minimize recall bias, and (3) they provided additional consent to perform the survey study. Patients from four paediatric nephrology centres in four Canadian provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, and Quebec) were recruited. Research ethics board approval was obtained at each study site before initiating the study and parental consent and child assent (as appropriate) were obtained for the survey.

Survey procedure

A research assistant performed a telephone or in-person survey with the legal guardian(s) of the participant. The survey was designed to elicit information chiefly on health care utilization related to the presenting symptoms of nephrotic syndrome prior to diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome.

Survey instrument

We developed the survey questions (provided in Appendix) and piloted the survey with two patients and two clinicians to ensure face and content validity. The questions and format were modified according to feedback from these individuals. The final version of the survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete and was composed of three main sections:

(1) Questions to collect patient (i.e., age, sex, ethnicity, medical history) and family (i.e., combined family income, legal guardians’ highest education, residence location, ownership of pets) demographic characteristics.

(2) Questions to assess where the patient presented, what diagnosis was given at each health care encounter, and what treatments were suggested. This set of questions was repeated for each health care visit up to the visit in which the patient was diagnosed correctly with nephrotic syndrome.

(3) Questions regarding missed work and school, and patient and family expenses prior to correct diagnosis. Parents or guardians were also asked to qualitatively describe the patient experience.

Variables

The relevant exposure variables were divided into two categories: (1) patient-level variables (sex, age, ethnic origin, and history of allergies); (2) family-level variables (total combined household income, ownership of pets, highest degree of education of the parents/legal guardians, and residence location).

We defined our primary outcome variable as ‘diagnostic success’, during a health care visit. We categorized all given diagnoses as correct, incorrect or incomplete. A correct diagnosis was defined as (1) identification of nephrotic syndrome or a kidney disease causing protein leakage into the urine, or (2) referral to a nephrologist. An incorrect diagnosis was defined as a diagnosis other than nephrotic syndrome or kidney disease. A diagnosis was considered incomplete if there was no definitive diagnosis or if a workup for symptoms was performed: example cases include the physician ordering further tests, stating uncertainty or referring the patient to another physician (e.g., paediatrician, but not nephrologist).

Secondary outcomes included: (1) the most common incorrect diagnoses; (2) health care history, including number of visits and diagnoses given during visit; (3) diagnostic delay, defined as time from first presentation of symptoms as remembered by participant to date of correct diagnosis.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to report patient and family demographics of the cohort, using means (± standard deviations), medians (interquartile ranges) as appropriate. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. The unit of analysis was health care visits (i.e., any visit related to presenting nephrotic syndrome symptoms, until a correct diagnosis was obtained). We described the number of health care visits prior to diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome and determined the proportion of diagnostic success for each visit (either correct, incorrect, incomplete) by health care setting (emergency room, walk-in clinic, paediatric clinic, family medicine clinic, or other). We also described the types of diagnoses given to patients other than ‘nephrotic syndrome’. The qualitative comments regarding the diagnostic journey the participants provided were summarized in tabular format.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the association between obtaining a correct diagnosis and health care setting utilized at a given visit, while adjusting for potential confounding variables (sex, age, and ethnicity). In the regression analysis, family medicine and walk-in clinic settings were grouped. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Study cohort

Among 124 eligible patients with a diagnosis of childhood nephrotic syndrome, 76 (61.2%) patients consented for the survey. Two patients were excluded due to missing data. Demographic information is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients and families1

| Characteristic (n = 74 patients) | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex | Males: 50% |

| Females: 50% | |

| Age Range at Correct Diagnosis (n = 72) | 1.2–14.8 years |

| Median: 4.8 | |

| IQR: 5.1 | |

| Ethnic Origin (n = 71) | Caucasian: 54% |

| Non-Caucasian: 46% (includes 20% | |

| Asian, 14% mixed) | |

| Known Allergies | Yes: 16% |

| No: 84% | |

| Combined household income before taxes per year | Less than $35,000: 23% |

| $35,000 – less than $100,000: 26% | |

| $100,000 or more: 42% | |

| Choose not to answer: 9% | |

| Residential Setting | Urban: 72% |

| Rural: 28% |

1Two observations were missing for Age Range and three were missing for Ethnic Origin.

Health care locations and diagnostic success

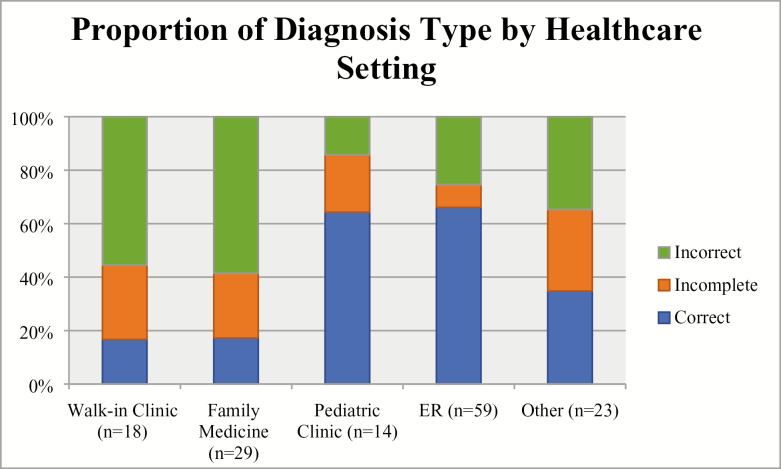

There were a total of 143 health care visits among 74 patients (excluding visits to nephrologists). Of these visits, patients were given a correct diagnosis 44.8% of the time. The median number of visits prior to diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome was 2 (interquartile range [IQR]: 1 to 3 visits). A majority of patients visited emergency room doctors (59 visits, 41.2%) or family doctors (29 visits, 20.3%). In emergency room settings (n = 59 visits), the proportion of correct diagnoses (66.1%) was substantially higher than incomplete (8.5%) and incorrect (25.4%) diagnoses. Paediatric settings (n = 14 visits) also had a high proportion of correct diagnoses (64.3%) compared to incomplete (21.4%) and incorrect (14.3%) diagnoses. In family medicine settings (n = 29), the proportion of correct diagnoses (17.2%) was lower than incorrect diagnoses (58.6%). Similarly, in walk-in clinic settings (n = 18), the proportion of correct diagnoses (16.7%) was also low compared to incorrect diagnoses (55.6%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of diagnosis type by health care setting

The adjusted odds of obtaining a correct diagnosis in an emergency room setting was almost five times higher when compared with adjusted odds of obtaining a correct diagnosis in a family medicine or walk-in clinic setting (odds ratio 4.82; 95% confidence interval 2.12 to 11.00).

Types of diagnoses and diagnostic delays

Of the incorrect diagnoses given to patients, ‘allergies’ was the most common (47.4%), although only 12/74 (16.2%) of patients reported having allergies in the past medical history. The remaining incorrect diagnoses were comprised of infection (14.0%), cold/flu (10.5%), and eye problems (8.8%), and other (19.3%). Incomplete diagnoses, given in 18.9% of visits, included ordering further tests and referring the patient to another health care centre (other than a nephrologist).

The diagnostic delay patients experienced ranged from 0 to 428 days (median 9.5, IQR = 20.5). Patients who had a diagnostic delay of 0 to 1 days had a median of one health care visit, while patients who had a diagnostic delay greater than 8 days had a median of two health care visits.

Patient health care experience

Fifty per cent of the participants reported incurring expenses (e.g., transportation costs, nonprescription medicines) prior to obtaining a correct diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome. Participation in regular activities was also affected for both patients and caregivers: 55.4% of the parents missed work and 68.1% of the patients missed school during the time prior to obtaining a correct diagnosis. Of the parents missing work, 31.7% missed greater than 30 hours of work, and of the children missing school, 40.8% missed greater than 30 hours of school. A summary of the comments provided by the participants regarding the diagnostic journey is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Qualitative comments from families on the diagnostic experience

| Parent 1 | “I was frustrated because they have urine strips at the clinic, but they never thought to use them” |

| Parent 2 | “I thought it might be a kidney problem because of the swollen eyes but they ensured me it was an allergy” |

| Parent 3 | “I was hoping one of the doctors here would figure out what was wrong. When I sent the pictures of my child to my relative who is a medical student overseas, he got back to us in 5 minutes with the correct diagnosis” |

| Parent 4 | “We saw the same ER doctor 5 times! The doctor just kept diagnosing allergies and increased the dosage of Benadryl each time” |

DISCUSSION

Delayed and incorrect diagnoses of nephrotic syndrome are common. Proportion of diagnostic success is less than 20% in primary care settings compared to almost 70% in emergency care settings. Substantial proportions of patients experience missed work and school related to health care visits to diagnose nephrotic syndrome. Greater diagnostic success in emergency and paediatric care settings compared to walk-in clinics and family medicine (both primary care) settings suggest that health care settings affect diagnostic success.

There are several potential reasons for differences in diagnostic success between health care settings. One plausible explanation is that the differences may be related to nephrotic syndrome being a rare disease and lack of staff experience in primary care settings with the symptoms of disease (1,7,8). Difficulties in diagnosing nephrotic syndrome appear to be comparable to those of other rare diseases. Previous survey research has shown that almost 20% of primary care physicians do not want to be involved with diagnosis of rare diseases, and reported that it was difficult to know clinical presentations of numerous rare diseases. Over 50% feel their knowledge of a given rare disease is only fair or poor at the time of diagnosis, compared to neutral, good, or excellent (7). Furthermore, up to 40% of patients with a rare disease are initially given an incorrect diagnosis, and most patients suffering from a rare disease first present in a family medicine setting (9,10).

Another possible factor is the need for application of the appropriate diagnostic tests: the key test for diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome is urinalysis (which can be done in the doctor’s office or sent to the laboratory) to identify proteinuria and consequently indicate kidney disease (3). Lack of familiarity with the disease and presenting symptoms may lead to decreased use of urinalyses in primary care settings, despite urinalysis being a commonly available test in primary care settings (11). An additional challenge in diagnosing nephrotic syndrome is the nonspecificity of presenting symptoms, such as periorbital edema which is also commonly caused by allergies. Indeed, the most common incorrect diagnosis in our surveyed sample of patients was allergies, confirming many anecdotal reports from paediatric nephrology clinicians that their patients are often misdiagnosed with allergies.

As expected, our data showed that incorrect diagnoses, such as allergies, also led to delays in obtaining a correct diagnosis. Consequently, this would have affected administration of timely treatments. In many cases, repeated health care visits were necessary, and patients and families faced missed work and school as a result of need for more health care visits. In addition to increased health care visits, previous research has shown that patients with a rare disease experience self-doubt, anxiety, stress, and frustration in the time before obtaining a correct diagnosis (8,12). We can reasonably presume that these burdens are most likely exacerbated by delays and errors in diagnoses. Therefore, prompt diagnosis may improve quality-of-life and satisfaction with health care for patients and families (7).

Our study has a number of limitations. First, there was an inability to control for severity of symptoms; for example, patients presenting to emergency room settings may have had more severe symptoms. Second, there is a possibility of recall bias: the accuracy of information obtained from guardians may differ depending on the elapsed time between diagnosis and survey date. We tried to minimize this effect by restricting the study to patients who presented within 24 months prior to completing our survey. Third, we were also not able to control for concurrent illness (such as upper respiratory tract infections) which may have complicated diagnosis and treatment of nephrotic syndrome. Finally, the sample of patients surveyed was a convenience sample from four Provinces, although the survey was embedded in a national cohort study of nephrotic syndrome. Therefore, the results represent the experience of the surveyed patients. Generalizability to other patients’ experience may differ depending on delivery and availability of health care across the country.

This study revealed low proportions of success in diagnosing childhood nephrotic syndrome in primary care settings. Implementation of educational tools to recognize nephrotic syndrome, and appropriate use of urinalysis to diagnose proteinuria may help address low proportions of diagnostic success and improve the patient health care experience.

Source of Funding: Canadian Institutes for Health Research and Kidney Foundation of Canada.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Eddy AA, Symons JM. Nephrotic syndrome in childhood. Lancet. 2003;362(9384):629–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holt RC, Webb NJ, Bernstein J, Edelmann C, Barratt T, Postlethwaite R. Management of nephrotic syndrome in childhood. Curr Paediatr. 2002;12(7):551–60. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dolan NM, Gill D, Sharma RK, et al. Management of nephrotic syndrome. Paediatr Child Health (Oxford). 2008;18(8):369–74. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sinha A, Bagga A. Nephrotic syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79(8):1045–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krishnan RG, Kemper MJ, Callard RE, Barratt TM. Nephrotic syndrome. Paediatr Child Health (Oxford). 2012;22(8):337–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Samuel S, Scott S, Morgan C, et al. The Canadian childhood nephrotic syndrome (CHILDNEPH) project: Overview of design and methods. Can J Kidney Heal Dis. 2014;1:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Engel PA, Bagal S, Broback M, Boice N. Physician and patient perceptions regarding physician training in rare diseases: The need for stronger educational initiatives for physicians. J Rare Disord. 2013;1(2):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zurynski Y, Frith K, Leonard H, Elliott E. Rare childhood diseases: How should we respond?Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(12):1071–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Knight AW, Senior TP. The common problem of rare disease in general practice. Med J Aust. 2006;185(2):82–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eurordis Rare Diseases Europe. Survey of the delay in diagnosis for 8 rare diseases in Europe (‘EurordisCare2) 2006. Available from: http://www.eurordis.org/sites/default/files/publications/Fact_Sheet_Eurordiscare2. pdf (cited August 21, 2017).

- 11. Altman SH, Socholitzky E. The cost of ambulatory care in alternative settings: A review of major research findings. Annu Rev Public Health. 1981;2:117–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blöß S, Klemann C, Rother A-K, et al. Diagnostic needs for rare diseases and shared prediagnostic phenomena: Results of a German-wide expert Delphi survey. Palau F, editor. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0172532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.