Abstract

Background

This systematic review qualitatively summarizes the current literature on diagnosis and treatment of oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD) after total laryngectomy (TLE).

Methods

Electronic databases PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library were used. Two independent reviewers carried out the literature search and assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using a critical appraisal tool.

Results

Forty‐four articles met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 35 studies were on diagnosis, four on therapy, and five on both diagnosis and treatment of OD following TLE. Study aims, swallowing‐assessment methods, and main findings of the included studies were summarized and presented.

Conclusions

The reviewers found heterogeneous outcomes and serious methodological limitations, which prevented us from pooling data to identify trends that would assist in designing best clinical practice protocols for OD following TLE. Further research should focus on several remaining gaps in our knowledge on diagnosis and treatment interventions for OD following TLE.

Keywords: deglutition disorders, dysphagia, pharyngolaryngectomy, swallowing disorder, total laryngectomy

1. INTRODUCTION

Total laryngectomy (TLE) is a surgical procedure commonly used in the treatment of advanced stage laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer. It involves resection of the entire larynx and separation of the respiratory and digestive tracts. A neopharynx is created by closing the surgical defect of the pharynx, either directly or if necessary with different types of pedicled or free flaps. The pharyngeal mucosa can be surgically removed if a partial or total pharyngectomy or even esophagectomy is oncologically indicated. A surgical airway is established by placing a permanent tracheostomy. The main purpose of TLE is complete removal of the cancerous tissue. Preservation of swallowing function and restoration of speech function are important secondary goals. However, a (salvage) TLE can also be performed for management of chronic aspiration, airway compromise, radionecrosis, and tumor recurrence.1 Unless fistulisation or voice prosthesis leakage occurs, there is no risk of aspiration after uncomplicated TLE. Other dysphagia signs and symptoms may occur due to impaired bolus transport. A common symptom following TLE is oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD), with a frequency ranging from 10% to 60%.2, 3 The main complaints reported by TLE patients are regurgitation, food “sticking” in the throat, globus sensation, or a prolonged mealtime.4, 5

Frequently used instrumental tools to evaluate swallowing function are videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS)6, 7 and manometry.6 Swallowing impairment can also be evaluated from the patients' perspective, using self‐report dysphagia questionnaires such as the M.D. Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI), Swallowing Quality‐of‐Life questionnaire (SWAL‐QoL), Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck cancer patients (PSS‐HN), and the EAT‐10.7, 8 The aim of the evaluation is to determine the cause and severity of the swallowing impairment and to guide the selection of an effective treatment. A variety of OD treatment approaches after TLE and partial laryngectomy have been described, notably diet modification, compensation strategies, swallowing maneuvers, surgical interventions such as botulinum toxin A injections, and endoscopic dilatation for strictures.5

Few studies have been published on the diagnosis and treatment of OD following TLE. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no systematic review has yet been published on this topic. The present study assesses the current literature on diagnosis and treatment of OD after TLE. The aim of preparing an evidence‐based overview was to support clinical decision making and guide the development of treatment strategies.

2. IDENTIFICATION AND SELECTION OF STUDIES

A literature search using the electronic databases Embase, PubMed, and the Cochrane library was carried out by 2 independent investigators. Their search strategy is presented in Table 1. Only articles on diagnosis and treatment for OD after TLE with or without (partial) pharyngectomy or extended resections toward the esophagus in adults were included. Peer‐reviewed journal articles written in the English, German, Portuguese, Spanish, French, or Dutch language with more than 10 study participants were included. The search was limited to articles published from January 1995 through November 2017. Studies involving experiments on animals or presenting a consensus or an expert opinion were excluded. Articles were also excluded if swallowing outcomes were not presented in the results. Studies solely on esophageal dysphagia were excluded too. The two reviewers independently identified, selected, and qualitatively assessed the studies. Differences were resolved by consensus and a third reviewer was consulted if consensus could not be reached. Reference lists of the included studies were checked for additional literature. Inter‐rater agreement for definitive inclusion based on full text was calculated using Cohen's kappa coefficient. A flow diagram of the study selection was reported according to PRISMA.9

Table 1.

Systematic syntax

|

PubMed

((((laryngectomy[MeSH Terms]) OR laryngectom*) OR post laryngectomy)) AND ((((deglutition disorder[MeSH Terms]) OR dysphag*[Title/Abstract]) OR deglut*[Title/Abstract]) OR swallow*[Title/Abstract]) |

|

Embase

((laryngectomy/or laryngectom*.mp.) AND (dysphagia/or swallowing/or deglut*.mp. or swallow*.mp or dysphag*.mp.)) |

|

The Cochrane Library MeSH terms

([laryngectomy]) AND ([deglutition disorders]) |

|

The Cochrane Library free‐text

(laryngectom*) AND (dysphag* OR deglut* OR swallow*) |

3. DATA ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT OF STUDY QUALITY

The ABC rating scale developed by Siwek et al was used to determine the level of evidence.10 Level A refers to high‐quality randomized controlled trials, level B to well‐designed nonrandomized clinical trials, and level C to expert opinion, consensus, or case series. As there was no validated tool to assess the quality of both diagnostic and therapeutic studies, a list of quality assessment criteria derived from Reitsma et al and Whiting et al11, 12 was created (Table 2).

Table 2.

Critical appraisal criteria for methodological quality assessment

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Were subject characteristics sufficiently described? |

| 2 | Were selection criteria clearly described? (inclusion and exclusion criteria) |

| 3 | Was an explanation for drop‐outs provided? |

| 4 | Were study aims reported? |

| 5 | Did all patients undergo the same standardized assessment or therapy protocol? |

| 6 | Were the outcome measurements and/or therapy program described in sufficient detail to allow replication of the study? |

| 7 | Were the raters blinded to the group and to each other's results? |

| 8 | Were results reported in sufficient detail? |

| 9 | Were statistical analytic methods used? |

The first two items of the critical appraisal tool assessed generalizability (external validity), items 3‐8 assessed reliability (internal validity), and item 9 assessed the statistical methods.

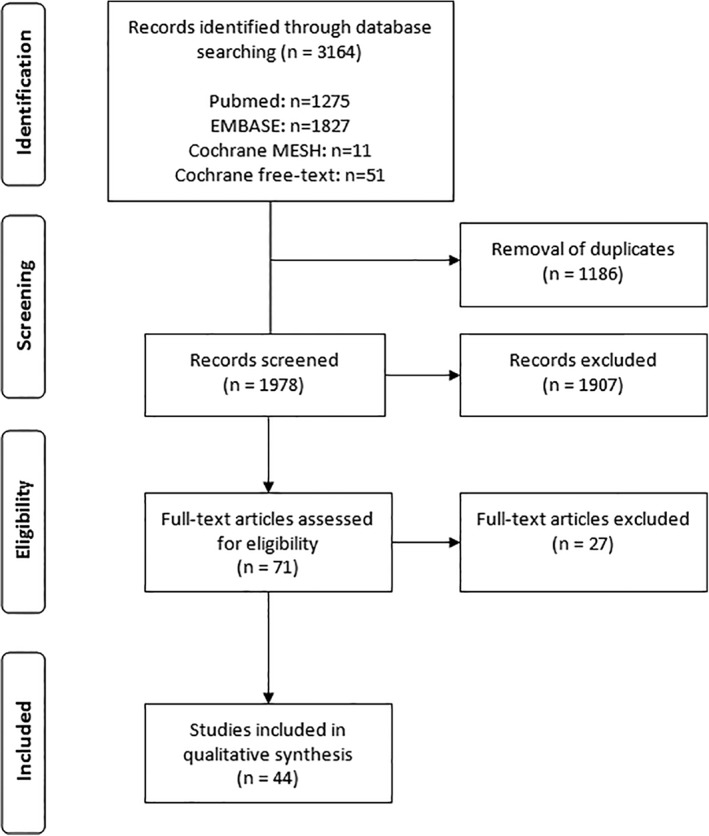

4. General results

In the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases, 3164 records were identified (Figure 1). Inter‐rater agreement on inclusion based on full text was κ = 0.74, indicating substantial agreement. After discussion, full consensus was achieved on all selected studies. A search for additional literature in the reference lists of the included articles did not yield additional studies. The critical appraisal assessment is presented in Table 3. Level of evidence, subject number, study aims, swallowing assessment methods, and authors' key findings of the 44 included articles are summarized in Tables 4, 5, 6. Studies on diagnosis of OD after TLE are presented in Table 4. Studies on treatment effect for OD after TLE are described in Table 5. Table 6 presents studies combining diagnosis and treatment effects on OD after TLE. A meta‐analysis comparing swallowing assessment tools or surgical techniques (TLE; TLE with partial pharyngectomy and flap reconstruction; total pharyngolaryngectomy with flap, jejunum reconstruction, or gastric pull‐up; etc.) was planned but not carried out, as the studies were not of sufficient quality to warrant doing so.

Figure 1.

PRISMA study selection diagram

Table 3.

Methodological quality assessment per item per included study

| Included studies | Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | Item 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armstrong et al21 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Arenaz Búa et al22 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Barbiera et al45 | U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Barrett et al56 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U | N | U | N |

| Bergquist et al48 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Burnip et al36 | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Chone et al18 | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Culie et al30 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | U | Y |

| de Casso et al27 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | U | Y |

| Georgiou et al43 | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Graville et al23 | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Harris et al51 | Y | U | Y | U | Y | N | N | U | N |

| Hui et al16 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U | N | U | Y |

| Hui et al19 | U | U | U | Y | Y | U | N | U | Y |

| Kelly et al49 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | N |

| Kazi et al41 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Krappen et al14 | U | U | Y | U | Y | Y | N | U | N |

| Kreuzer et al24 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Lewin et al25 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y |

| Lightbody et al53 | U | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | U | N |

| LoTempio et al20 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y |

| Maclean et al38 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Maclean et al39 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Maclean et a35 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Natt et al52 | U | Y | Y | U | Y | U | N | U | N |

| Oozeer et al40 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | U | Y |

| Oursin et al55 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | N | N | U | N |

| Pauloski et al15 | U | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Pernambuco et al46 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y |

| Pernambuco et al50 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Pillon et al42 | U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Pitzer et al54 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | N | N | U | N |

| Puttawibul et al33 | U | U | U | Y | Y | U | N | U | Y |

| QueijaDdos et al17 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Regan et al47 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y |

| Robertson et al37 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Sharp et al31 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Sommer et al34 | U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | N |

| Sweeny et al32 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

| Szuecs et al29 | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Tian et al13 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| van der Kamp et al26 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Ward et al28 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Zhang et al44 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

Abbreviations: N, no (did not meet criteria); U, unclear (insufficient information is provided); Y, yes (met criteria).

Table 4.

Diagnosis of oropharyngeal dysphagia following TLE

| Author and ref. | Level of evidence | Number of subjects and TLE patients | Study aim | Swallowing assessment method(s) | Authors' key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental swallowing assessments | |||||

| Kreuzer et al24 | B (retrospective cohort study) |

N = 120 N = 55 TLE |

Determine the incidence and spectrum of swallowing complications post‐surgery G1: TLE (n = 55) G2: Partial laryngectomy (n = 65) |

VFSS | Structural and functional disorders of the neopharynx after TLE included pharyngeal weakness (11%), pharyngoesophageal dysfunction (13%), strictures (15%), fistula formation (11%), and mass‐lesions (24%). |

| Lewin et al25 | B (retrospective cohort study) |

N = 58 TLE | Compare swallowing outcomes and complication rates for a jejunal interposition graft versus ALT flap G1: Jejunal interposition graft (n = 31) G2: ALT flap (n = 27) |

VFSS; diet tolerated | ALT flap had better swallowing outcome (eg, greater return to oral intake, less post‐swallow residue, and less impaired tongue base retraction) than the jejunal interposition graft but similar complication rates. |

| Sommer et al34 | B (case‐control study) |

N = 43 N = 17 TLE |

Investigate swallowing function after reconstruction with microvascular anastomosis transplants G1: Tongue reconstruction with infrahyoid muscle flap (n = 15) G2: Soft palate reconstruction with infrahyoid muscle flap or radial forearm flap (n = 11) G3: Larynx and pharynx reconstruction with jejunum siphon with or without repair of the digastric muscle (n = 17) |

Perfusion manometry | Better pharyngeal pressure gradients were seen for jejunum siphon with repair of the digastric muscle compared to no digastric repair after TLE. |

| Krappen et al14 | B (prospective cohort study) |

N = 36 N = 16 PLE |

Identify functional changes in swallowing after cancer treatment G1: (Sub)total tongue resection (n = 12) G2: Total soft palate and velum resection (n = 8) G3: Total PLE with jejunal flap (n = 16) |

Cineradiography | All patients with pharynx reconstruction had no problems with bolus transfer through the reconstructed pharynx. |

| Pauloski et al15 | B (prospective cohort study) |

N = 29 TLE | Compare swallowing function after pharyngeal plexus neurectomy and/or pharyngeal constrictor myotomy for prevention of pharyngospasm. G1: Pharyngeal constrictor myotomy (n = 10) G2: Pharyngeal plexus neurectomy (n = 9) G3: Pharyngeal plexus neurectomy with (drainage) myotomy (n = 10) |

VFSS | Neurectomized patients had lower oropharyngoesophageal swallow efficiencies (amount of bolus swallowed during the total transit time) than either the myotomized or the combined procedure group. |

| Barbiera et al45 | C (case series) |

N = 21 N = 14 TLE/PLE |

Investigate neopharyngeal disorders after partial laryngectomy or TLE G1: TLE (n = 12) G2: Total PLE (n = 2) G3: Partial laryngectomy (n = 7) |

Digital cineradiography; Water Siphon test | All TLE and PLE patients showed morphological and functional disorders of the neopharynx, including parapharyngeal diverticulum (14%), pseudodiverticulum (43%), fistulas (14%), lumen narrowing/stenosis (14%), tumor recurrence (7%), prominent cricopharynx (36%), and rhinopharyngeal reflux (29%). |

| Pernambuco et al46 | C (case series) |

N = 15 TLE | Describe the electrical activity of the masseter muscle during swallowing after TLE | sEMG | TLE patients presented electrical activity of the masseter during swallowing and at rest. The electrical activity of the masseter was influenced by bolus volume. |

| Regan et al47 | C (case series) |

N = 10 TLE | To obtain measurements of pharyngoesophageal segment distensibility and opening during swallowing | Endoflip | Pharyngoesophageal segment cross‐sectional area and intraballoon pressure increased during distensions. |

| Combined instrumental swallowing assessments and swallow‐related questionnaires | |||||

| Burnip et al36 | B (cross‐sectional study) |

N = 124 N = 67 TLE |

Investigate swallowing outcomes following TLE and/or (chemo)radiotherapy: G1: TLE (n = 17) G2: Radiotherapy + TLE (n = 41) G3: Radiotherapy (n = 26) G4: Chemoradiotherapy (n = 31) G4: Chemoradiotherapy + TLE (n = 9) |

Water swallow test; PSS‐HN; MDADI | Swallowing outcomes were worse (more diet restrictions) for patients who received chemoradiotherapy and TLE. |

| van der Kamp et al26 | B (retrospective cohort study) |

N = 66 TLE | Evaluate whether vertical closure or T‐shaped closure is more associated with pseudodiverticulum formation and postoperative dysphagia. G1: Vertical closure (n = 39) G2: T‐shaped closure (n = 27) |

SWAL‐QoL; VFSS | Pseudodiverticulum was more frequently seen after vertical closure compared to T‐shaped closure. The frequency of dysphagia was higher in patients with a pseudodiverticulum than in patients without a pseudodiverticulum. |

| Hui et al16 | B (prospective cohort study) |

N = 52 TLE | Determine how much residual mucosa is sufficient for primary closure without causing dysphagia after TLE | Clinical measurements; barium swallow | In the absence of recurrent malignancy, a pharyngeal remnant width of 1.5 cm relaxed or 2.5 cm stretched was adequate to maintain swallowing function after primary closure. |

| Puttawibul et al33 | B (retrospective cohort study) |

N = 48 PLE | Determine long‐term swallowing function after pharyngolaryngo‐esophagectomyand gastric pull‐up | Body weight; interview; gastrograffin swallowing | Patients with a gastric pull‐up reconstruction showed postoperatively an improved nutritional status and 90% of the patients could eat regular food with occasional regurgitation. |

| Culie et al30 | B (retrospective cohort study) |

N = 34 TLE | Evaluate functional outcomes after salvage surgery | DOSS; clinical measurements | The mean of the pre‐operative DOSS score was higher than the post‐operative scores, indicating less severe dysphagia pre‐operatively. |

| Queija Ddos et al17 | B (prospective cohort study) |

N = 28 TLE/PLE | Determine swallowing characteristics and swallow‐related QoL after TLE and PLE with T‐shaped closure G1: TLE (n = 15) G2: PLE (n = 13) |

SWAL‐QoL; VFSS | Complaints of dysphagia were associated with higher burden and lower mental health scores on SWAL‐Qol. VFSS showed anatomical and functional changes in preparatory‐oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing. |

| Maclean et al35 | B (case‐control study) |

N = 24 TLE | Determine the impact of TLE and surgical closure technique on swallow biomechanics and dysphagia severity | Australian TOM; Videomanometry |

Following TLE, pharyngeal propulsive contractile forces were impaired, and there was increased resistance to bolus flow across the pharyngoesophageal segment. |

| Chone et al18 | B (prospective cohort study) |

N = 20 TLE | Evaluate the degree of dysphagia before and after TLE | PSS‐HN; VFSS | “Eating in public” and “normalcy of diet” scores decreased in 50% of patients after TLE. Lower scores on PSS‐HN were related to pharyngoesophageal spasm. |

| Hui et al19 | B (prospective cohort study) |

N = 11 TLE | Investigate the relationship between the size of the neopharynx after TLE and long‐term swallowing function | Scintigraphy; interview | The swallowing function was not affected by the size of the neopharynx in 11 patients with a 3‐8 cm pharyngeal remnant width (stretched). |

| Bergquist et al48 | C (case series) |

N = 10 TLE | Evaluate long‐term functional outcomes in patients with a free jejunal transplant reconstruction after pharyngolaryngo‐esophagectomy | KPSSI; dysphagia grading according to Ogilvie et al; Watson dysphagia score; EORTC QLQ‐C30; EORTC QLQ‐OES18;VFSS |

Radiologic signs of disturbed bolus passage after free jejunal reconstruction were common, but their clinical impact seemed questionable since all patients reported relatively mild dysphagia and generally good QoL. |

| Kelly et al49 | C (case series) |

N = 10 PLE | Examine long‐term swallowing and eating outcomes after a gastric pull‐up reconstruction | PSS‐HN; gastric pull‐up swallowing questionnaire; clinical measurements; VFSS | Patients who underwent a gastric pull‐up procedure maintained postoperatively a healthy weight, ate in a range of environments, and consumed a normal diet. |

| Swallow‐related questionnaires | |||||

| Robertson et al37 | B (cross‐sectional study) |

N = 179 TLE | Determine the effect of radiotherapy on functional outcomes after TLE G1: TLE alone (n = 26) G2: TLE and postoperative radiotherapy (n = 88) G3: Salvage TLE (n = 65) |

MDADI; UW‐QoL | Radiotherapy had a detrimental effect on swallowing outcomes after TLE. Better median MDADI scores were seen for primary TLE versus salvage TLE and primary TLE with postoperative radiotherapy. |

| de Casso et al27 | B (retrospective cohort study) |

N = 121 TLE | Determine the effect of radiotherapy on swallowing after TLE G1: TLE (n = 26) G2: Salvage TLE (n = 95) |

Medical charts and data from speech‐language therapist; diet | Preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy adversely affected swallowing. |

| Maclean et al38 | B (cross‐sectional study) |

N = 110 TLE | Investigate the effect of dysphagia on QoL, functioning, and psychological well‐being after TLE | WHO QoL‐BREF; UW‐QoL; DASS | Patients with dysphagia following TLE had an impaired functioning and reduced social participation measured by UW‐QoL and higher levels of depression and anxiety measured by DASS. |

| Maclean et al39 | B (cross‐sectional study) |

N = 110 TLE | Investigate the prevalence and nature of self‐reported dysphagia after TLE | Twenty‐one‐item questionnaire battery | The dysphagia prevalence following TLE was 72%. Dysphagia resulted in significant dietary changes and it had a negative impact on activities and social participation. |

| Ward et al28 | B (retrospective cohort study) |

N = 92 TLE/PLE | Determine the incidence of dysphagia and examine the impact of persistent dysphagia after TLE G1: TLE (n = 55) G2: PLE (n = 37) |

Medical charts and speech pathology files; interview; TOM dysphagia scale | 58% of the TLE patients and 50% of the PLE patients had dysphagia (3 years postoperatively). Long‐term dysphagia resulted in increased levels of disability, handicap, and distress. |

| Oozeer et al40 | B (cross‐sectional study) |

N = 79 TLE | Assess swallowing function after TLE G1: ≤6 months postoperative (n = 30) G2: 6‐12 months postoperative (n = 19) G3: ≥12 months postoperative (n = 30) |

PSS‐HN | PSS‐HN scores improved over time, especially the “public eating” domain, indicating greater confidence in eating. |

| Szuecs et al29 | B (retrospective cohort study) |

N = 76 N = 28 TLE |

Determine the impact of (chemo)radiotherapy with(out) TLE on swallowing function G1: Definitive (chemo)radiotherapy (n = 21) G2: TLE+(chemo)radiotherapy (n = 28) G3: Larynx conservation surgery+(chemo)radiotherapy (n = 27) |

Swallowing questionnaire | Dysphagia and PEG feeding were more frequently found after (chemo)radiotherapy compared to TLE+(chemo)radiotherapy. |

| Graville et al23 | B (prospective cohort study) |

N = 67 TLE | Comparison of long‐term functional and QoL outcomes after TLE with primary closure and TLE with non‐circumferential radial free forearm tissue transfer (RFFTT) reconstruction G1: TLE + primary closure without adjuvant treatment (n = 16) G2: TLE + primary closure and history of radiation with(out) chemotherapy (n = 34) G3: TLE + RFFTT with(out) any adjuvant treatment (n = 17) |

PSS‐HN; MDADI | The RFFT group had significantly higher rates of chemotherapy, G‐tube at surgery, and postoperative strictures. Diet and swallowing outcomes were comparable between the three groups; all patients resumed an oral diet and no one had a G‐tube at long‐term follow up. |

| Kazi et al41 | B (cross‐sectional study) |

N = 62 TLE | Determine the effect of TLE on swallowing and QoL | MDADI | Most patients had postoperatively a high total score on MDADI, indicating a low impact of dysphagia on QoL. Glossectomy and the method of pharyngeal closure significantly affected swallowing. No difference in MDADI scores was seen for myotomized compared to nonmyotomized patients. |

| LoTempio et al20 | B (prospective cohort study) |

N = 49 N = 34 TLE |

Compare QoL outcomes after chemoradiotherapy or TLE with radiotherapy G1: Chemoradiotherapy (n = 15) G2: TLE+ post‐operative radiotherapy (n = 34) |

UW‐QoL | Both the chemoradiotherapy and TLE + radiotherapy group reported high overall UW‐QoL scores and thus good health‐related QoL. Pain, swallowing, and chewing impairment were more frequently reported in the chemoradiotherapy group. |

| Arenaz Búa et al22 | B (prospective cohort study) |

N = 45 TLE | Determine the occurrence of swallowing problems in TLE patients and to investigate if dysphagia was related to age, time after TLE, radiotherapy, and TNM‐classification | SSQ | The prevalence of swallowing problems was 89%. Dysphagia severity was not related to age, time after TLE, T classification or performance of neck dissection. Dysphagia was significantly associated with substitution voice problems after TLE. |

| Pillon et al42 | B (cross sectional study) |

N = 36 N = 25 TLE |

Investigate the presence of swallowing difficulties and diet modifications after TLE and partial laryngectomy G1: TLE (n = 25) G2: Frontolateral laryngectomy (n = 11) |

Semi‐structured interview | 48% reported eating difficulties post‐TLE, mostly related to solid foods. Food consistency modifications, head maneuvers, and decreased oral food intake were compensation methods frequently reported. |

| Armstrong et al21 | B (prospective cohort study) |

N = 34 TLE | Investigate the progress of QoL from the preoperative stage up to 6 months after TLE | SF‐36; patient questionnaire; outcome measures questionnaire | Swallowing difficulties persisted for many laryngectomees up to 6 months postsurgery. Forty‐two percent of the TLE patients reported that dysphagia prevented them from eating out in public. Prevention from eating out in public was correlated with prolonged mealtime and a modified‐texture diet. |

| Georgiou et al43 | B (cross‐sectional study) |

N = 23 TLE | Evaluate the impact of dysphagia on QoL after TLE | EAT‐10; MDADI | Dysphagia had a negative impact on QoL. Adjuvant therapy led to more frequent dysphagia symptoms than TLE alone. |

| Sharp et al31 | B (retrospective cohort study) |

N = 19 PLE | Investigate long‐term functional swallowing outcomes and QoL following PLE with a jejunal flap | RBHOMS; TOM dysphagia scale; swallow assessment by a speech‐language pathologist | Following a PLE with jejunal reconstruction, 89% of the patients showed no to mild dysphagia and tolerated an oral diet. Patients with dysphagia reported increased levels of “disability,” “handicap,” and “distress” on TOM. |

| de Pernambuco et al50 | C (case series) |

N = 15 TLE | Describe the effect of deglutition on QoL after TLE | SWAL‐QoL | Dysphagia had a moderate to severe impact on the “communication,” “fear,” and “eating duration” domains of the SWAL‐QoL. |

Abbreviations: ALT flap, anterolateral thigh free flap; DASS, depression anxiety and stress scale; DOSS, dysphagia outcome and severity scale; EAT‐10, eating assessment tool 10; EORTC QLQ‐C30 or QLQ‐OES 18, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire ‐ Core 36 or esophageal cancer module 18; G‐tube, gastrostomy tube; KPSSI, Karnofsky performance status scale index; MDADI, the M.D. Anderson Dysphagia Inventory; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; PLE, pharyngolaryngectomy; PSS‐HN, performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients; QoL, quality of life; RBHOMS, Royal Brisbane Hospital outcome measure for swallowing; sEMG, surface electromyography; SF‐36, short form survey 36; SSQ, Sydney Swallow Questionnaire; SWAL‐QoL, Swallowing Quality‐of‐Life questionnaire; TLE, total laryngectomy; TOM, therapy outcome measure; UW‐QoL, University of Washington Quality of Life questionnaire; VFSS, videofluoroscopic swallowing study; WHOQoL‐BREF, World Health Organization Quality of Life instrument—abbreviated version.

Table 5.

Treatment effects for oropharyngeal dysphagia after TLE

| Author and ref. | Level of evidence | Number of subjects and TLE patients | Study aim | Swallowing assessment method(s) | Authors' key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tian et al13 | B (lower quality randomized controlled trial) |

N = 65 TLE | Investigate the effect of psychological adjustments on swallow‐related quality of life after TLE G1: Routine communication (n = 20) G2: Patient‐to‐patient communication (n = 20) G3: Physician communication (n = 25) |

SWAL‐QoL; VAS | Patient‐to‐patient communication model can be used to resolve swallowing problems caused by psychological factors. SWAL‐QoL scores were higher in patient‐to‐patient communication and physician communication than in the routine communication group. |

| Harris et al51 | C (case series) |

N = 20 TLE | Evaluate the efficacy of radiologically guided balloon dilatation for treatment of dysphagia secondary to neopharyngeal strictures | Clinical measurements | Balloon dilatations for neopharyngeal strictures were minimally invasive, safe, well‐tolerated, effective, and may be repeated frequently. |

| Natt et al52 | C (case series) |

N = 15 TLE | Evaluate the efficacy of botulinum toxin A injections for cricopharyngeus dysphagia | VFSS; telephone interview; body weight | Percutaneous botox injections demonstrated a 60% success rate in treating dysphagia. 87% of the patients had an overall improvement in symptoms (eg, food “sticking” in throat). |

| Lightbody et al53 | C (case series) |

N = 13 TLE | Evaluate the efficacy of transcutaneous botulinum toxin A injections for pharyngoesophageal spasm | VFSS; UW‐QoL; MDADI | Botox injections were safe and effective for treatment of pharyngoesophageal spasm post‐TLE. There was an improvement of 10.2% in the MDADI scores and 7.6% in the UW‐QoL scores overall. |

Abbreviations: MDADI, the M.D. Anderson Dysphagia Inventory; SWAL‐QoL, Swallowing Quality‐of‐Life questionnaire; TLE, total laryngectomy; UW‐QoL, University of Washington Quality‐of‐Life Questionnaire; VAS, visual analogue scale; VFSS, videofluoroscopic swallowing study.

Table 6.

Diagnosis and treatment effect for oropharyngeal dysphagia after TLE

| Author and ref. | Level of evidence | Number of subjects and TLE patients | Study aim | Swallowing assessment method(s) | Authors' key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweeny et al32 | B (retrospective cohort study) |

N = 263 TLE | Determine the incidence and risk factors for stricture formation; and survey the differences between patients who received neoadjuvant or concurrent radiation versus surgery as initial treatment G1: Stricture group (n = 49) G2: Nonstricture group (n = 214) Intervention: Endoscopic dilatation |

VFSS | One‐third of the TLE patients experienced dysphagia, whereas 19% developed a stricture (rates were similar for TLE versus salvage TLE). Neopharyngeal strictures could be managed with single or serial dilatations to maintain nutritional intake. |

| Zhang et al44 | B (cross‐sectional study) |

N = 30 TLE | Characterize pharyngeal biomechanics in patients with dysphagia after TLE Intervention: Endoscopic dilatation of PEJ |

Videomanometry; SSQ | Both impaired pharyngeal propulsion and increased pharyngeal outflow resistance were reported. Increased pharyngeal outflow resistance was the major contributing factor for dysphagia. Baseline PEJ resistance and its decrement postdilatation were predictors of treatment outcome. |

| Pitzer et al54 | C (case series) |

N = 20 TLE | Investigate the incidence, symptoms, and treatment for a neopharyngeal pseudodiverticulum after TLE Intervention: Endoscopic CO2‐laser treatment |

Barium swallow; interview; clinical assessment | Fifty‐five person of the TLE patients had a pseudodiverticulum of which 82% had dysphagia. Eighty‐nine percent of the patients with a pseudodiverticulum gained relief of the dysphagic symptoms after treatment with a CO2 laser. |

| Oursin et al55 | C (case series) |

N = 20 TLE | Determine the frequency and correlation with clinical symptoms of a pseudodiverticulum Intervention: Endoscopic laser therapy |

Barium swallow; indirect laryngoscopy | Sixty percent of the TLE patients had a pseudodiverticulum of which two‐thirds complained of dysphagia. All symptomatic patients were successfully treated with endoscopic laser therapy. |

| Barrett et al56 | C (case series) |

N = 17 TLE | Assess the effect of postoperative radiation on swallow function in patients with a jejunal interposition graft after pharyngolaryngo‐esophagectomy Intervention: Endoscopic dilatation |

Subjective swallow function; body weight; gastrostomy tube; jejunal dilatations; barium swallow | The jejunal interposition grafts were irradiated, usually with good swallow outcomes: 71% of the patients with an irradiated jejunal interposition graft were able to obtain adequate oral nutrition and 29% required (intermittent) dilatations to maintain nutrition. |

Abbreviations: PEJ, pharyngoesophageal junction; SSQ, Sydney swallow questionnaire; TLE, total laryngectomy; VFSS, videofluoroscopic swallowing study.

5. METHODOLOGICAL QUALITY

None of the studies was rated level A. Thirty‐two studies were rated level B and 12 studies level C, according to Siwek et al.10 Level B studies comprised one low‐quality randomized controlled trial,13 ten prospective cohorts,14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 ten retrospective cohorts,24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 two case‐control studies,34, 35 and nine cross‐sectional studies.36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 All case series were classified as level C evidence.45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56 None of the 44 articles met all critical appraisal criteria (Table 3). Seventeen articles fulfilled all criteria for external validity,13, 17, 22, 26, 27, 28, 30, 32, 35, 36, 38, 39, 40, 44, 46, 49, 50 and six studies did not fulfill any of these criteria.14, 19, 33, 34, 42, 45 Two of the included articles fulfilled all criteria for internal validity,18, 48 representing a low risk of bias. Fourteen articles met only 2‐3 criteria for internal validity,14, 16, 19, 27, 30, 33, 36, 40, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56 indicating a high risk of bias. Thirty studies applied statistical analytic methods.13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 46, 47

6. DIAGNOSIS OF OD AFTER TLE

In total, 40 of the 44 studies described a diagnosis of OD after TLE with or without pharyngeal reconstruction (Tables 4 and 6). Ten studies used instrumental swallowing assessments, 16 studies used self‐report questionnaires, and 14 studies combined instrumental swallowing assessments and questionnaires to evaluate OD. In the following subsections, studies on diagnosis of OD are summarized according to the applied swallowing assessment method (instrumental assessment or questionnaires). It was not possible to pool all the included studies according to the applied surgical technique (with or without pharyngeal reconstruction) due to heterogeneity or unclear description. Only ten studies specifically described the technique of pharynx reconstruction or primary closure. A paragraph describing swallowing function after a specific surgical technique is introduced in the next subsection.

6.1. Instrumental swallowing assessment

This subsection presents a summary of the functional and anatomical signs of OD per study. A diversity of swallowing assessment methods were applied after TLE with or without pharyngeal reconstruction: VFSS15, 17, 18, 24, 25, 26, 32, 48, 49; cineradiography14, 45; videomanometry35, 44; perfusion manometry34; barium swallow16, 54, 55, 56; scintigraphy19; gastrograffin swallow33; sEMG46; functional lumen imaging (Endoflip)47; and the Dysphagia Outcome and Severity Scale (DOSS) assessed with barium swallow.30 The time interval from surgery to swallowing assessment ranged from five days24 to 23 years.49 The most frequently used instrumental swallowing assessment technique was VFSS.

Various neopharyngeal findings after primary pharynx closure were reported as contributing to OD. Among these, the main ones were impaired pharyngeal propulsion,35, 44 increased pharyngeal outflow resistance,35, 44 pharyngeal weakness,24 pharyngoesophageal dysfunction,24 pharyngoesophageal spasm,18 and nasopharyngeal reflux.45 According to some authors, swallowing function was not affected by the diameter of the neopharynx after primary closure with a pharyngeal remnant width ranging from 3 to 8 cm.16, 19

The reported frequency of the main structural disorders of the neopharynx with or without pharyngeal reconstruction was as follows: 15% to 19% stricture formation24, 32; 42% to 60% pseudodiverticulum formation35, 45, 54, 55; 4% to 18% fistulas16, 17, 19, 24, 31, 33, 45; 7% to 13% tumor recurrence16, 45; and 22% to 36% prominent cricopharyngeal muscle.17, 45 The frequency of pseudodiverticulum formation seemed to be dependent on the type of pharyngeal closure.26 A pseudodiverticulum was more frequently seen after vertical closure compared to T‐shaped neopharyngeal closure.26 Radiographic signs of disturbed bolus transport through the jejunal interposition graft were commonly observed after total pharyngolaryngectomy,25, 48 whereas Krappen et al14 observed no problems with bolus transport after pharynx reconstruction with a tubed jejunal interposition graft with siphon. Interestingly, pathologic (regional) lymph node involvement (N classification ≥ 1) was a significant predictor of poorer postoperative DOSS scores in the study by Culie et al.30 Due to the wide divergence between study designs and outcome measurements, the intended pooling of date was not possible, which prevented a comparison of swallowing function per surgical technique.

6.2. Swallowing after primary closure or pharynx reconstruction

Ten studies described swallowing function after pharynx reconstruction that was performed with different types of pedicled or microvascular free flaps versus primary closure.14, 23, 25, 26, 32, 33, 34, 35, 41, 49 Better swallowing function, as assessed by cineradiography,14 VFSS,25, 26 perfusion manometry,34 videomanometry,35 or MDADI,41 was reported after mucosa‐and‐muscle pharyngeal primary closure (eg, T‐shaped, Y‐shaped, or vertical closure) compared to only mucosa primary closure,35 after T‐shaped pharyngeal closure compared to vertical closure or circumferential closure,26, 41 after horizontal pharyngeal closure compared to vertical closure,41 after ALT flap compared to jejunal graft interposition,25 and after insertion of a jejunum siphon with repair of the digastric muscle versus insertion without repair of the digastric muscle.14, 34 Higher rates of stricture formation, as assessed with VFSS, were seen for primary pharyngeal closure versus a pedicled or microvascular free flap reconstruction32; higher rates of stricture formation were also seen for tubed radial forearm flap compared to patch radial forearm flap.32 Furthermore, no significant differences in PSS‐HN and MDADI scores were seen between patients who underwent a primary TLE versus patients who underwent a pharyngolaryngectomy with noncircumferential radial free forearm tissue transfer.23 According to some authors, patients who had undergone a laryngopharyngoesophagectomy with a gastric pull‐up procedure showed postoperative improvement: they had a healthy weight, could eat in public, and consumed a normal diet.33, 49 If swallowing impairments occurred after a gastric pull‐up procedure, the most common functional limitations were regurgitation, prolonged mealtime, and reduced quantity of oral intake per meal.33, 49

6.3. Questionnaires

This subsection presents a summary of the responses to the questionnaires that were administered. Eleven studies used swallow‐related questionnaires such as the MDADI,23, 36, 37, 41, 43 SWAL‐QoL,17, 26, 50 University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire,20, 37, 38 and EAT‐10.43 Twelve studies used health‐related questionnaires or clinician‐rated assessment tools: the PSS‐HN,18, 36, 40, 49 Therapy Outcome Measure (TOM) dysphagia scale,28, 31, 35 World Health Organization Quality of Life Instruments,38 Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale,38 Short Form survey 36,21 Sydney Swallow Questionnaire (SSQ),22, 44Watson Dysphagia score,48 and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ‐C30 and QLQ‐OES18).48 Other methods to collect swallow‐related data such as semi‐structured interviews,19, 28, 33, 42, 54 clinical assessments,19, 33, 49, 54, 56 data collected by the speech‐language therapist,27, 28, 31 or self‐designed questionnaires21, 29, 39, 49 were described too. The time interval from surgery to filling out the questionnaires ranged from one month21, 42 up to 27 years.37 Only four studies compared preoperative to postoperative data from the questionnaires.18, 21, 30, 33 In all but two studies,19, 33 participants underwent (neo)adjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy. (Chemo)radiotherapy performed either preoperatively or postoperatively adversely affected swallowing.20, 27, 29, 36, 37, 43 The prevalence of OD after TLE ranged from 35% to 89%21, 22, 32, 39, 42, 43 and the incidence of OD after TLE was 58%.28 The main OD symptoms reported in the studies were the following: prolonged mealtime, need for fluids to wash down a bolus, multiple swallows, avoidance of certain food consistencies, pain, coughing while eating, food “sticking” in the throat, regurgitation, and gastroesophageal reflux.17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 27, 28, 29, 33, 35, 39, 42, 48, 49, 50, 54 Patients usually experienced OD with solid foods, resulting in significant changes in their diets (liquid diet, pureed foods, etc.).39, 42, 48 Ten studies reported a negative impact of OD on the patients' QoL.17, 18, 21, 28, 31, 38, 39, 40, 43, 50 OD had a negative impact on all MDADI domains,43 on the SWAL‐QoL domains “feeding duration,” “communication,” “fear,” “mental health,” and “general burden,”17, 50 and on the TOM subscales “handicap,” “well‐being and distress,” and “disability.”28, 31 OD prevented patients from eating out in public18, 21, 39, 40 and resulted in a reduced amount of social participation.38, 39 No correlations were found between self‐report health‐related QoL questionnaires and the outcome of diverse swallowing instrumental assessments.17, 48

7. TREATMENT EFFECTS FOR OD AFTER TLE WITH AND WITHOUT PHARYNGEAL RECONSTRUCTION

In total, nine studies concerning treatment effects for OD were identified (Tables 5 and 6). Six of these described surgical treatment for OD,32, 44, 51, 54, 55, 56 two described pharmacological treatment,52, 53 and in one study dysphagic TLE patients were treated with a coping strategy.13

7.1. Surgical treatment for OD

Four studies investigated the effect of dilatation of neopharyngeal strictures after primary pharyngeal closure or after a pedicled or microvascular free flap reconstruction32, 44, 51, 56 and two studies investigated the effects of endoscopic laser therapy of a neopharyngeal pseudodiverticulum.54, 55 Radiological guided balloon dilatation was reported to relieve strictures, as measured by symptomatologic relief of OD symptoms, of the neopharynx without serious complications.51 Endoscopic dilatation(s) of neopharyngeal strictures resulted in improved dietary outcomes and a significant decrease in pharyngoesophageal junction resistance observed during VFSS, videomanometry, and barium swallows, which was correlated with symptomatic improvement of OD.32, 44, 56 Two studies reported improved OD symptoms using a barium swallow and clinical assessment after endoscopic laser therapy for anterior neopharyngeal pseudodiverticulum without clinically relevant postoperative complications.54, 55

7.2. Pharmacological treatment for OD

Botulinum toxin A injections used as a treatment for cricopharyngeal dysphagia improved swallowing function (measured with VFSS) and swallow‐related QoL in two studies.52, 53

7.3. Coping strategy for OD

The effect of psychological treatments for OD following TLE was investigated by Tian et al.13 The domains “fear of eating” and “mental health” on SWAL‐QoL were the main ones related to OD after TLE. Patients were randomly divided into three communication groups to resolve their swallowing problems: a patient‐to‐patient communication group (volunteer TLE patients shared their own experiences about OD), a routine communication group (no additional communication about OD), and a physician communication group (discussions about OD with two surgeons who had performed the procedure). The patient‐to‐patient communication treatment model resulted in higher scores on SWAL‐QoL (less severe OD complaints) compared to the physician and routine communication treatment models, at 1 month postoperatively. However, no differences on SWAL‐QoL were seen between these three treatment modalities at one year posttreatment. In addition, lower SWAL‐QoL scores representing greater impact of dysphagia on QoL were seen two weeks postoperatively in patients with a higher educational background compared to those with a lower educational background.

8. METHODOLOGICAL COMMENTS

This systematic review is the first one to summarize and methodologically evaluate the evidence on diagnosis and treatment of OD after TLE with or without pharyngeal reconstruction. It covers 44 articles that reported on swallowing function following TLE. Data pooling was not possible due to the heterogeneity of the assessment tools, the diversity of the study populations, and the poor methodological quality of the investigations. All of the included studies had one or more methodological limitations. Seventeen studies had a good external validity. Most studies reported inclusion but no exclusion criteria14, 16, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 29, 31, 33, 34, 37, 41, 42, 43, 45, 47, 48, 51, 54, 55, 56 or did not sufficiently describe patient characteristics.14, 15, 18, 19, 33, 34, 42, 45, 52, 53 These omissions introduce the potential for selection and reporting bias.12 In 14 studies, extrapolation of the results to all TLE patients can be compromised due to the poor internal validity or small sample sizes (≤20 study participants).18, 19, 31, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56 The overall internal validity of 44 studies was of moderate quality. Study aims and explanation for dropouts were reported in the majority of the studies. In two studies, patients with OD were included, but no information was provided on how OD was diagnosed.45, 52 Furthermore, Ward et al28 was the only study that presented a well‐written definition of OD. The absence of a clear definition in almost all studies and a wide variety of swallowing outcome measures can explain the wide range of OD prevalence among the included studies.

Reproducibility may be compromised in several studies because no detailed information on the swallowing assessment protocol or therapy program was provided.16, 19, 25, 27, 30, 32, 33, 49, 51, 52, 54, 55, 56 Additionally, in some studies not all patients underwent the same swallowing assessment protocol.15, 36, 40, 44, 49, 53 Translation of the results to best clinical decision making is not possible in 18 studies because the methodology and results were not described in sufficient detail to warrant doing so.14, 16, 19, 20, 26, 27, 30, 33, 34, 40, 46, 47, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56 Information on the number of raters and how exams were evaluated was missing in almost all studies. Only in five studies were the raters blinded15, 18, 26, 48, 49 and only in three studies was information given on interobserver or intraobserver reliability.15, 18, 48 One should interpret the results reported in this systematic review with caution because of the compromised generalizability, reliability, and high risk of bias identified in several of the included studies.

9. DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF OD

The pathophysiology of swallowing disorders in TLE patients is multifactorial. It may be due to radiotherapy, pharyngeal closure technique, the extent of additional pharyngeal mucosa resection, and postoperative complications.14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 41, 43, 45, 49, 54, 55 The most frequently reported functional and/or structural complications of the neopharynx causing OD were pharyngeal weakness, increased resistance to bolus passage, strictures, and pseudodiverticulum formation.16, 17, 19, 24, 31, 32, 33, 35, 45, 54, 55 A couple of studies compared swallowing function following different types of pharyngeal closure and reconstruction techniques.14, 23, 25, 26, 32, 33, 34, 35, 41, 49 Horizontal and T‐shaped closures were the most commonly used closure techniques. However, it remains unclear which surgical closure technique is the best for efficient swallowing, and that question needs further investigation. In this systematic review, it was not possible to stratify swallowing outcomes per surgical technique due to a great variation in the methods used (TLE with primary closure, TLE with partial pharyngectomy and flap reconstruction, total pharyngolaryngectomy with different flap reconstructions, gastric pull‐up, etc.), the great heterogeneity in study designs, and the lack of high‐quality studies.

(Neo)adjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy had a negative impact on swallowing function in several studies although a detailed description of the applied technique, timing, and type of (chemo)radiation (preoperative vs postoperative, intensity‐modulated radiotherapy vs conventional techniques, protocol of primary (chemo)radiation in case of salvage TLE vs postoperative radiotherapy in case of primary TLE, the total radiation dose [in Gray], the fractionation schedule, the overall treatment time, exact target volumes, etc.) was missing in most studies.20, 27, 29, 36, 37, 43 OD may occur after (neo)adjuvant radiotherapy due to xerostomia, pain, tissue swelling, fibrosis, lymphedema, or radiotherapy‐induced sensorial neuropathy.4 Deglutition disorders had a negative impact on swallow‐related QoL and resulted in significant changes in the diet of TLE patients.17, 18, 21, 28, 31, 38, 39, 40, 42, 43, 48, 50 This indicates that the impact of OD needs careful evaluation because it is patient specific and thus highly variable. In addition, a great variation in questionnaires evaluating the impact of swallowing impairment on patients' QoL was seen among the included studies.

At the moment, no dysphagia‐specific QoL or symptom questionnaire is available that has been validated for the population of TLE patients. The use of questionnaires such as the MDADI and the SSQ among others is debatable because these instruments were not validated for this patient population. These questionnaires include questions targeted at aspiration such as deglutitive cough which are not applicable to TLE patients. However, there is no good alternative at present and the authors hope that a specific tool with good psychometric properties for this group will be developed in the future. The absence of guidelines for swallow assessment in TLE patients and the lack of validated measurements in this population might explain why these studies used such a great diversity of self‐report questionnaires. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of the swallowing outcome measurements, different postoperative measurement times, the various methods of pharyngeal reconstruction, and whether or not (chemo)radiation was administered during the course of treatment made it impossible for us to draw comparisons between the studies or to observe trends. Therefore, to ensure more robust findings in future studies, validated and standardized swallowing assessment methods are necessary as well as a detailed description of the applied surgical technique and exact information on (chemo)radiation protocols during the course of treatment. Few articles on treatment effects for OD after TLE were found and there was no consensus on what is the best OD treatment for this population. Some preliminary studies showed promising results of botulinum toxin A injections, endoscopic (balloon) dilatations, and CO2 laser therapy. However, significant treatment results or trends were not found. This points to the need for well‐designed randomized controlled trials using validated multidimensional swallowing assessment protocols to evaluate OD after TLE and to investigate the clinical applicability of treatment techniques.

10. CONCLUSIONS

OD after TLE is a common finding. The cause is multifactorial and it results in oral intake adaptation and impaired health‐related QoL. The reviewers found heterogeneous outcomes and serious methodological limitations, which prevented them from pooling the data to analyze possible trends that would assist in designing best clinical practice protocols for OD following TLE. Further research should focus on the remaining gaps found in the literature on the diagnosis of and treatment interventions for OD following TLE.

Terlingen LT, Pilz W, Kuijer M, Kremer B, Baijens LW. Diagnosis and treatment of oropharyngeal dysphagia after total laryngectomy with or without pharyngoesophageal reconstruction: Systematic review. Head & Neck. 2018;40:2733–2748. 10.1002/hed.25508

Contributor Information

Lisanne T. Terlingen, Email: l.terlingen@student.maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Laura W. Baijens, Email: laura.baijens@mumc.nl.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hutcheson KA, Alvarez CP, Barringer DA, Kupferman ME, Lapine PR, Lewin JS. Outcomes of elective total laryngectomy for laryngopharyngeal dysfunction in disease‐free head and neck cancer survivors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(4):585‐590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balfe DM, Koehler RE, Setzen M, Weyman PJ, Baron RL, Ogura JH. Barium examination of the esophagus after total laryngectomy. Radiology. 1982;143(2):501‐508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crary MA, Glowasky AL. Using botulinum toxin A to improve speech and swallowing function following total laryngectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122(7):760‐763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murphy BA, Gilbert J. Dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiation: assessment, sequelae, and rehabilitation. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2009;19(1):35‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Landera M, Lundy D, Sullivan P. Dysphagia after total laryngectomy. Perspect Swal Swal Dis. 2010;19:39‐44. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coffey M, Tolley N. Swallowing after laryngectomy. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;23(3):202‐208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Frowen JJ, Perry AR. Swallowing outcomes after radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Head Neck. 2006;28(10):932‐944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sullivan PA, Hartig GK. Dysphagia after total laryngectomy. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;9(3):139‐146. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, Group TP . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Siwek J, Gourlay ML, Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. How to write an evidence‐based clinical review article. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(2):251‐258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reitsma JB, Rutjes AW, Whiting P, Vlassov VV, Leeflang MMG, Deeks JJ. Chapter 9: assessing methodological quality In: Deeks JJ, Bossuyt PM, Gatsonis C, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Version 1.0.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tian L, An R, Zhang J, Sun Y, Zhao R, Liu M. Effect of the patient‐to‐patient communication model on dysphagia caused by total laryngectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 2017;131(3):253‐258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krappen S, Remmert S, Gehrking E, Zwaan M. Cinematographic functional diagnosis of swallowing after plastic reconstruction of large tumor defects of the mouth cavity and pharynx. Laryngorhinootologie. 1997;76(4):229‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pauloski BR, Blom ED, Logemann JA, Hamaker RC. Functional outcome after surgery for prevention of pharyngospasms in tracheoesophageal speakers. Part II: swallow characteristics. Laryngoscope. 1995;105(10):1104‐1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hui Y, Wei WI, Yuen PW, Lam LK, Ho WK. Primary closure of pharyngeal remnant after total laryngectomy and partial pharyngectomy: how much residual mucosa is sufficient? Laryngoscope. 1996;106(4):490‐494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Queija Ddos S, Portas JG, Dedivitis RA, Lehn CN, Barros AP. Swallowing and quality of life after total laryngectomy and pharyngolaryngectomy. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;75(4):556‐564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chone CT, Spina AL, Barcellos IH, Servin HH, Crespo AN. A prospective study of long‐term dysphagia following total laryngectomy. B‐ENT. 2011;7(2):103‐109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hui Y, Ma KM, Wei WI, et al. Relationship between the size of neopharynx after laryngectomy and long‐term swallowing function: an assessment by scintigraphy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124(2):225‐229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. LoTempio MM, Wang KH, Sadeghi A, Delacure MD, Juillard GF, Wang MB. Comparison of quality of life outcomes in laryngeal cancer patients following chemoradiation vs. total laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132(6):948‐953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Armstrong E, Isman K, Dooley P, et al. An investigation into the quality of life of individuals after laryngectomy. Head Neck. 2001;23(1):16‐24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arenaz Bua B, Pendleton H, Westin U, Rydell R. Voice and swallowing after total laryngectomy. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017;138(2):170‐174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Graville DJ, Palmer AD, Chambers CM, et al. Functional outcomes and quality of life after total laryngectomy with noncircumferential radial forearm free tissue transfer. Head Neck. 2017;39(11):2319‐2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kreuzer SH, Schima W, Schober E, et al. Complications after laryngeal surgery: Videofluoroscopic evaluation of 120 patients. Clin Radiol. 2000;55(10):775‐781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lewin JS, Barringer DA, May AH, et al. Functional outcomes after circumferential pharyngoesophageal reconstruction. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(7):1266‐1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van der Kamp MF, Rinkel R, Eerenstein SEJ. The influence of closure technique in total laryngectomy on the development of a pseudo‐diverticulum and dysphagia. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(4):1967‐1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Casso C, Slevin NJ, Homer JJ. The impact of radiotherapy on swallowing and speech in patients who undergo total laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(6):792‐797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ward EC, Bishop B, Frisby J, Stevens M. Swallowing outcomes following laryngectomy and pharyngolaryngectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(2):181‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Szuecs M, Kuhnt T, Punke C, et al. Subjective voice quality, communicative ability and swallowing after definitive radio(chemo)therapy, laryngectomy plus radio(chemo)therapy, or organ conservation surgery plus radio(chemo)therapy for laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer. J Radiat Res. 2015;56(1):159‐168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Culie D, Benezery K, Chamorey E, et al. Salvage surgery for recurrent oropharyngeal cancer: post‐operative oncologic and functional outcomes. Acta Otolaryngol. 2015;135(12):1323‐1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sharp DA, Theile DR, Cook R, Coman WB. Long‐term functional speech and swallowing outcomes following pharyngolaryngectomy with free jejunal flap reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(6):743‐746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sweeny L, Golden JB, White HN, Magnuson JS, Carroll WR, Rosenthal EL. Incidence and outcomes of stricture formation postlaryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(3):395‐402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Puttawibul P, Pornpatanarak C, Sangthong B, et al. Results of gastric pull‐up reconstruction for pharyngolaryngo‐oesophagectomy in advanced head and neck cancer and cervical oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Asian J Surg. 2004;27(3):180‐185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sommer K, Burk C, Sommer T, Remmert S. Perfusion manometry in the evaluation of postoperative swallowing function following various reconstructive procedures of the upper aero‐digestive tract. Laryngorhinootologie. 1997;76(3):178‐185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maclean J, Szczesniak M, Cotton S, Cook I, Perry A. Impact of a laryngectomy and surgical closure technique on swallow biomechanics and dysphagia severity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(1):21‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burnip E, Owen SJ, Barker S, Patterson JM. Swallowing outcomes following surgical and non‐surgical treatment for advanced laryngeal cancer. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(11):1116‐1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Robertson SM, Yeo JC, Dunnet C, Young D, Mackenzie K. Voice, swallowing, and quality of life after total laryngectomy: results of the west of Scotland laryngectomy audit. Head Neck. 2012;34(1):59‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maclean J, Cotton S, Perry A. Dysphagia following a total laryngectomy: the effect on quality of life, functioning, and psychological well‐being. Dysphagia. 2009;24(3):314‐321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maclean J, Cotton S, Perry A. Post‐laryngectomy: it's hard to swallow: an Australian study of prevalence and self‐reports of swallowing function after a total laryngectomy. Dysphagia. 2009;24(2):172‐179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Oozeer NB, Owen S, Perez BZ, Jones G, Welch AR, Paleri V. Functional status after total laryngectomy: cross‐sectional survey of 79 laryngectomees using the Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck Cancer. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124(4):412‐416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kazi R, Prasad V, Venkitaraman R, et al. Questionnaire analysis of the swallowing‐related outcomes following total laryngectomy. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006;31(6):525‐530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pillon J, Goncalves MI, De Biase NG. Changes in eating habits following total and frontolateral laryngectomy. Sao Paulo Med J. 2004;122(5):195‐199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Georgiou AM, Kambanaros M. Dysphagia related quality of life (QoL) following total laryngectomy (TL). Int J Disabil Hum Dev. 2017;16(1):115‐121. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang T, Szczesniak M, Maclean J, et al. Biomechanics of pharyngeal deglutitive function following total laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155(2):295‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Barbiera F, Fiorentino E, Lo Greco V, et al. Digital cineradiography of the pharynx and the oesophagus after total or partial laryngectomy. Radiol Med. 2003;106(3):169‐177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pernambuco Lde A, Silva HJ, Nascimento GK, et al. Electrical activity of the masseter during swallowing after total laryngectomy. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;77(5):645‐650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Regan J, Walshe M, Timon C, McMahon BP. Endoflip(R) evaluation of pharyngo‐oesophageal segment tone and swallowing in a clinical population: a total laryngectomy case series. Clin Otolaryngol. 2015;40(2):121‐129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bergquist H, Andersson M, Ejnell H, Hellstrom M, Lundell L, Ruth M. Functional and radiological evaluation of free jejunal transplant reconstructions after radical resection of hypopharyngeal or proximal esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2007;31(10):1988‐1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kelly AM, Drinnan MJ, Savy L, Howard DJ. Total laryngopharyngoesophagectomy with gastric transposition reconstruction: review of long‐term swallowing outcomes. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122(12):1354‐1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pernambuco Lde A, Oliveira JH, Regis RM, et al. Quality of life and deglutition after total laryngectomy. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;16(4):460‐465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Harris RL, Grundy A, Odutoye T. Radiologically guided balloon dilatation of neopharyngeal strictures following total laryngectomy and pharyngolaryngectomy: 21 years' experience. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124(2):175‐179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Natt RS, McCormick MS, Clayton JM, Ryall C. Percutaneous chemical myotomy using botulium neurtoxin A under local anaesthesia in the treatment of cricopharyngeal dysphagia following laryngectomy. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37(4):500‐503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lightbody KA, Wilkie MD, Kinshuck AJ, et al. Injection of botulinum toxin for the treatment of post‐laryngectomy pharyngoesophageal spasm‐related disorders. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2015;97(7):508‐512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pitzer G, Oursin C, Wolfensberger M. Post‐laryngectomy anterior pseudodiverticulum [German]. HNO. 1998;46(1):60‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Oursin C, Pitzer G, Fournier P, Bongartz G, Steinbrich W. Anterior neopharyngeal pseudodiverticulum. A possible cause of dysphagia in laryngectomized patients. Clin Imaging. 1999;23(1):15‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Barrett WL, Gluckman JL, Aron BS. Safety of radiating jejunal interposition grafts in head and neck cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 1997;20(6):609‐612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]