Abstract

Objectives

Hyperhidrosis in pediatric patients has been understudied. Post hoc analyses of two phase 3 randomized, vehicle‐controlled, 4‐week trials (ATMOS‐1 [NCT02530281] and ATMOS‐2 [NCT02530294]) were performed to assess efficacy and safety of topical anticholinergic glycopyrronium tosylate (GT) in pediatric patients.

Methods

Patients had primary axillary hyperhidrosis ≥ 6 months, average Axillary Sweating Daily Diary (ASDD/ASDD‐Children [ASDD‐C]) Item 2 (sweating severity) score ≥ 4, sweat production ≥ 50 mg/5 min (each axilla), and Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS) ≥ 3. Coprimary end points were ≥ 4‐point improvement on ASDD/ASDD‐C Item 2 (a validated patient‐reported outcome) and change in gravimetrically measured sweat production at Week 4. Efficacy and safety data are shown through Week 4 for the pediatric (≥ 9 to ≤ 16 years) vs older (> 16 years) subgroups.

Results

Six hundred and ninety‐seven patients were randomized in ATMOS‐1/ATMOS‐2 (GT, N = 463; vehicle, N = 234); 44 were ≥ 9 to ≤ 16 years (GT, n = 25; vehicle, n = 19). Baseline disease characteristics were generally similar across subgroups. GT‐treated pediatric vs older patients had comparable improvements in ASDD/ASDD‐C Item 2 (sweating severity) responder rate, HDSS responder rate (≥ 2‐grade improvement]), sweat production, and quality of life (mean change from Baseline in Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI]/children's DLQI), with greater improvement vs vehicle. Treatment‐emergent adverse events were similar between subgroups, and most were mild, transient, and infrequently led to discontinuation.

Conclusions

Topical, once‐daily GT improved disease severity (ASDD/ASDD‐C, HDSS), sweat production, and quality of life (DLQI), with similar findings in children, adults, and the pooled population. GT was well tolerated, and treatment‐emergent adverse events were qualitatively similar between subgroups and consistent with other anticholinergics.

1. INTRODUCTION

Hyperhidrosis is characterized by excess sweat production beyond what is necessary to maintain thermal homeostasis. In primary hyperhidrosis, idiopathic sympathetic nerve hyperactivity triggers excess sweating, most commonly of the axillae, palms, soles, or craniofacial regions.1 Hyperhidrosis occurs in children and adults, with ~4.8% of the US population (~15.3 million people) affected.1, 2 In an online survey of US teens, ~17.1% experienced excessive sweating, with a mean onset age of 11 years.3 The substantial negative impact of hyperhidrosis on quality of life has been well established4, 5, 6, 7 and equated as comparable to, or greater than, the impact of psoriasis or eczema.8 In children, the condition negatively affects psychological and social development and well‐being, which may consequently trigger emotional and social distress.9

Hyperhidrosis largely remains underrecognized as a treatable medical condition, particularly for pediatric patients.6, 10 Only 51% of patients discussed their excess sweating with a health care professional, possibly due to patients' inability to recognize symptoms as a medical condition and/or dissatisfaction with available therapies.1, 11 Though not pediatric‐specific, these findings highlight the need for increased awareness and new treatments.6 Glycopyrronium tosylate (GT; formerly DRM04) is a topical anticholinergic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (June 2018) for primary axillary hyperhidrosis in patients 9 years and older (QBREXZA™ [glycopyrronium] cloth, 2.4%, for topical use). GT is applied once–daily to the axillae using a premoistened towelette. GT‐treated patients had decreased sweating severity and sweat production, with improvements in quality of life vs vehicle‐treated patients in two randomized, double‐blind vehicle‐controlled, pivotal phase three studies for primary axillary hyperhidrosis (ATMOS‐1, N = 344 [NCT02530281] and ATMOS‐2, N = 353 [NCT02530294]).12 ATMOS‐1 and ATMOS‐2 were the first randomized, controlled phase three trials in primary axillary hyperhidrosis to enroll pediatric patients, offering a unique perspective into this underserved population. To better characterize treatment outcomes in pediatric patients, pooled efficacy and safety data for pediatric (≥ 9 to ≤ 16 years) vs older patients (> 16 years) were evaluated in a post hoc analysis of ATMOS‐1 and ATMOS‐2.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

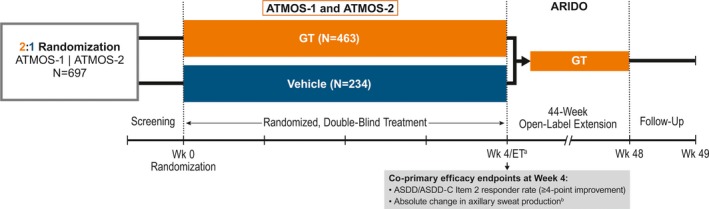

ATMOS‐1 (US and Germany sites) and ATMOS‐2 (US sites only) assessed the efficacy and safety of GT vs vehicle when applied once‐daily for 4 weeks (Figure 1). A detailed description of trial methodology and approval by local institutional review boards have been reported.12 Patients were assessed in clinics at Weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4 (end of treatment).

Figure 1.

- a ET for ATMOS‐1 and ATMOS‐2.

- bGravimetrically measured.

Patients not continuing in the open‐label extension (ARIDO) had a safety follow‐up at Week 5 via telephone.

ASDD, axillary sweating daily diary; ASDD‐C, ASDD‐Children; ET, end of treatment; GT, topical glycopyrronium tosylate; Wk, week

2.2. Study patients

Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are fully reported in the primary publication.12 Briefly, patients were male or nonpregnant females ≥ 9 years of age (≥ 18 years in Germany) with primary axillary hyperhidrosis for ≥ 6 months, gravimetrically measured sweat production ≥ 50 mg/5 min in each axilla, Axillary Sweating Daily Diary (ASDD)/ASDD‐Children (ASDD‐C) axillary sweating severity item (Item 2) ≥ 4 (11‐point scale),13, 14 and Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS) ≥ 3 (4‐point scale).

2.3. Efficacy and safety assessments

In ATMOS‐1 and ATMOS‐2, coprimary efficacy end points were ASDD/ASDD‐C Item 2 (sweating severity) responder rate (≥ 4‐point improvement from Baseline) and mean absolute change from Baseline in gravimetrically measured sweat production (average of left and right axillae) at Week 4.12 Whereas the adult ASDD assesses severity (Item 2), impact (Item 3), and bothersomeness (Item 4) of axillary sweating, the children's version only assesses severity (Item 2) and was completed by patients ≥ 9 to < 16 years. Item 2 was specifically developed and rigorously validated in accordance with FDA patient‐reported outcome (PRO) guidance15 to support efficacy assessments for regulatory approval. A 4‐point improvement was identified as the threshold for meaningful clinical response.14 Gravimetrically measured sweat production was assessed once a week over a 5‐minute period under controlled conditions across study sites.

ATMOS‐1 and ATMOS‐2 also assessed two additional PRO measures, namely the HDSS and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI; patients > 16 years) and children's version (CDLQI; patients ≤ 16 years). The HDSS, a validated hyperhidrosis‐specific PRO measure for assessing sweating severity, is a self‐reported questionnaire that employs a scale from 1 (never noticeable/never interferes with daily activities) to 4 (intolerable/always interferes with daily activities).16 Though widely used, the HDSS lacks a child‐specific version and does not conform to current regulatory standards for PRO measures used to support product approvals and labeling. The DLQI/CDLQI are not hyperhidrosis‐specific measures but are commonly used in dermatology clinical trials.17 These 10‐item, skin disease–specific questionnaires assess how symptoms and treatment affect patient health‐related quality of life. Higher scores on the 0‐30 numeric rating scales indicate lower quality of life.

This post hoc analysis reports pooled pediatric (≥ 9 to ≤ 16 years) vs older subgroup (> 16 years) data at Week 4, including ASDD/ASDD‐C Item 2 responder rate, mean and median absolute change from Baseline in gravimetrically measured sweat production, mean and median percent change from Baseline in sweat production, proportion of patients with ≥ 50% reduction in sweat production, HDSS responder rate (≥ 2‐grade improvement from Baseline), and mean change from Baseline in DLQI and CDLQI. Data by week through Week 4 are also presented. Safety assessments included treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and local skin reactions (LSRs).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Analysis subgroups were defined based on the DLQI and CDLQI, which have rigid age cutoffs for questionnaire administration (DLQI was administered to those > 16 years while CDLQI was administered to those ≤ 16 years). Therefore, the pediatric subgroup included patients ≥ 9 to ≤ 16 years and the older subgroup included patients > 16 years. Since ASDD/ASDD‐C Item 2 was psychometrically evaluated and validated, the standard age cutoffs (ASDD‐C: < 6 years; ASDD: ≥ 16 years) for questionnaire administration could be and were modified to match the subgroup definitions established by the DLQI/CDLQI. All efficacy and safety assessments were made according to these subgroup definitions.

Efficacy analyses were conducted on the intent‐to‐treat population (all patients who were randomized and dispensed study drug). Markov chain Monte Carlo multiple imputation was used at Weeks 1‐4. No imputation was made for DLQI/CDLQI. Analyses of statistical significance were not performed, as these comparisons were post hoc and not designed or powered to detect differences. Safety analyses were conducted on the safety population (all randomized patients who received ≥ 1 confirmed dose of study drug).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient disposition, demographics, and baseline disease characteristics

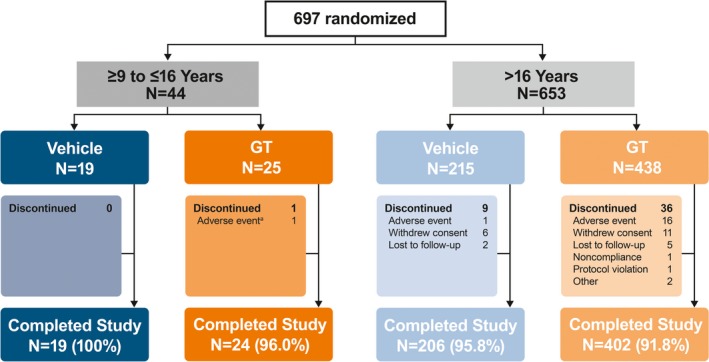

Of 697 patients randomized, 44 (GT, n = 25; vehicle, n = 19) comprised the pediatric subgroup (Figure 2). Completion rates were similar among subgroups and > 90%. Demographics and Baseline disease characteristics were generally well matched among treatment arms and between subgroups (Table 1). Although the older subgroup had greater gravimetrically measured sweat production at Baseline, the standard deviations were large across all treatment groups.

Figure 2.

- aPatient had five drug‐related events that led to discontinuation: mild vision blurred (bilateral), severe mydriasis (bilateral), severe dry mouth, severe urinary retention, and severe anhidrosis.

GT, topical glycopyrronium tosylate

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics

| ≥ 9 to ≤ 16 y | > 16 y | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle n = 19 | GT n = 25 | Vehicle n = 215 | GT n = 438 | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.1 (1.7) | 14.6 (1.4) | 35.1 (11.2) | 33.3 (10.5) |

| Median | 14.0 | 15.0 | 33.0 | 32.0 |

| Range | 9‐16 | 11‐16 | 17‐76 | 17‐65 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 4 (21.1) | 5 (20.0) | 110 (51.2) | 207 (47.3) |

| Female | 15 (78.9) | 20 (80.0) | 105 (48.8) | 231 (52.7) |

| White, n (%) | 17 (89.5) | 18 (72.0) | 179 (83.3) | 356 (81.3) |

| Weight (kg) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 64.8 (15.8) | 71.9 (15.7) | 84.3 (19.0) | 81.6 (19.3) |

| Median | 62.6 | 72.3 | 83.0 | 79.8 |

| Range | 47.2‐117.9 | 47.2‐107.7 | 45.8‐145.1 | 46.9‐149.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 24.0 (5.2) | 26.3 (5.6) | 28.1 (5.1) | 27.5 (5.4) |

| Baseline disease characteristics | ||||

| Years with axillary hyperhidrosis, mean (SD) | 4.6 (3.6) | 4.4 (4.1) | 17.0 (10.5) | 15.9 (10.8) |

| Sweat production (mg/5 min),a mean (SD) | 151.7 (150.6) | 145.8 (133.4) | 178.4 (163.0) | 174.0 (219.5) |

| ASDD/ASDD‐C Item 2 (sweating severity), mean (SD) | 6.7 (1.7) | 7.5 (1.2) | 7.2 (1.6) | 7.3 (1.6) |

| HDSS, n (%) | ||||

| Grade 3 | 14 (73.7) | 15 (60.0) | 141 (65.6) | 262 (59.8) |

| Grade 4 | 5 (26.3) | 10 (40.0) | 73 (34.0) | 176 (40.2) |

| DLQI,b mean (SD) | NAc | NAc | 10.6 (5.9) | 11.9 (6.1) |

| CDLQI, mean (SD) | 8.5 (5.6) | 9.9 (5.5) | NAc | NAc |

Intent‐to‐treat population.

ASDD, axillary sweating daily diary; ASDD‐C, ASDD‐Children; BMI, body mass index; CDLQI, children's DLQI; DLQI, dermatology life quality index; GT, topical glycopyrronium tosylate; HDSS, Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale; NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation.

Gravimetrically measured average from the left and right axillae.

n = 24 for GT group ≥ 9 to ≤ 16 y of age.

Patients ≥ 9 to ≤ 16 y of age were administered the CDLQI and patients > 16 y of age were administered the DLQI.

3.2. Efficacy

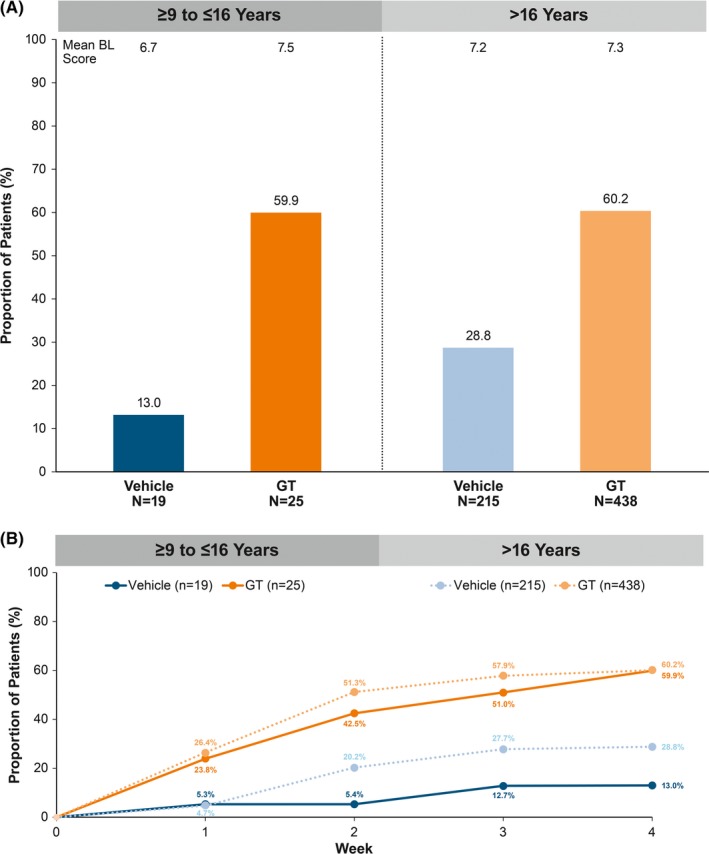

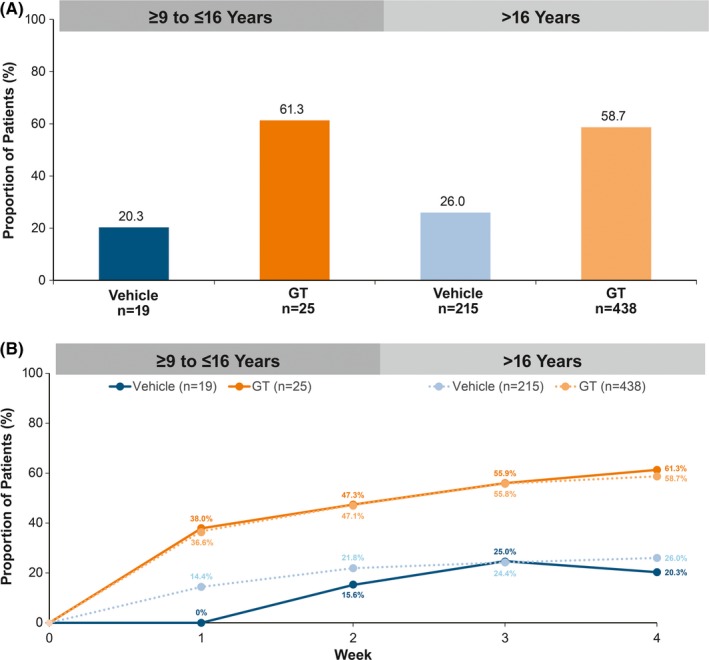

Efficacy results at Week 4 were consistent among subgroups and the overall pooled population.12 ASDD/ASDD‐C Item 2 responder rates were nearly identical among GT‐treated patients in the pediatric and older subgroups (59.9% vs 60.2%, respectively), and substantially greater for GT‐ vs vehicle‐treated patients regardless of subgroup (Figure 3A). Differences in responder rates between GT and vehicle were observed as early as Week 1 and were maintained through Week 4 in both subgroups (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

ASDD/ASDD‐C Item 2 responder rate (≥ 4‐point improvement). A, At Week 4. B, To Week 4. Intent‐to‐treat population. P‐values not calculated as these comparisons were post hoc and not designed or powered to detect differences. Multiple imputation (MCMC) was used to impute missing values for Weeks 1‐4. ASDD, Axillary Sweating Daily Diary; ASDD‐C, ASDD‐Children; BL, baseline; GT, topical glycopyrronium tosylate; MCMC, Markov chain Monte Carlo

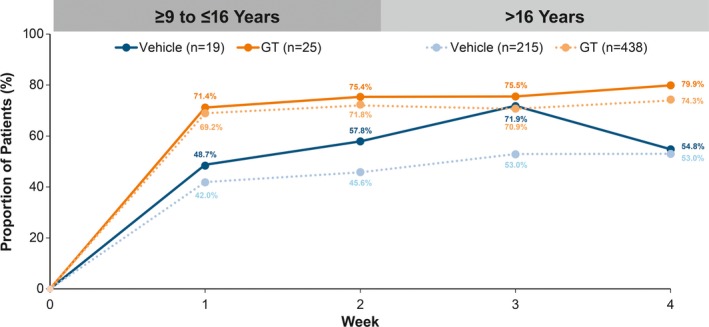

Median change in gravimetrically measured sweat production is presented here given the small pediatric sample size and skewness of the data (ie, large standard deviations) (Table 2). GT‐treated patients in the older subgroup had greater median absolute change from Baseline vs the pediatric subgroup (−80.6 vs −64.2 mg/5 minutes, respectively), and GT showed greater change vs vehicle in both subgroups. Mean percent change from Baseline in sweat production was similar among GT‐treated patients in pediatric and older subgroups (−60.1% vs −56.2%, respectively), and greater for GT‐ vs vehicle‐treated patients (Table 2). The proportion of patients with ≥ 50% reduction in sweat production at Week 4 was similar between GT‐treated pediatric and older patients (79.9% vs 74.3%; Table 2), with a markedly greater proportion of GT‐ vs vehicle‐treated patients achieving this reduction. Differences between GT and vehicle were observed as early as Week 1 and were maintained through Week 4 for both subgroups (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Assessments of sweat productiona

| ≥ 9 to ≤ 16 y | > 16 y | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle n = 19 | GT n = 25 | Vehicle n = 215 | GT n = 438 | |

| Absolute change from baseline at Week 4, mg/5 min | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −77.8 (110.6) | −67.9 (142.6) | −93.3 (141.9) | −109.9 (210.5) |

| Median | −53.7 | −64.2 | −62.0 | −80.6 |

| Percent change from Baseline at Week 4, mg/5 min | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −42.7 (38.2) | −60.1 (49.3) | −41.6 (47.9) | −56.2 (55.0) |

| Median | −55.3 | −75.4 | −54.1 | −74.2 |

| Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% reduction at Week 4, % | 54.8 | 79.9 | 53.0 | 74.3 |

Intent‐to‐treat population.

P‐values not calculated as these comparisons were post hoc and not designed or powered to detect differences; multiple imputation (MCMC) was used to impute missing values.

GT, topical glycopyrronium tosylate; MCMC, Markov chain Monte Carlo; SD, standard deviation.

Gravimetrically measured.

Figure 4.

- aGravimetrically measured average from the left and right axillae.

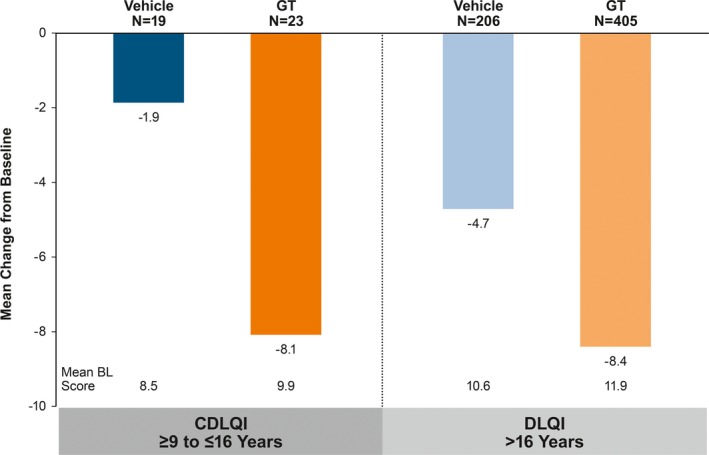

HDSS responder rates were similar among GT‐treated patients in the pediatric and older subgroups (61.3% vs 58.7%), and approximately threefold greater for GT‐ vs vehicle‐treated patients (Figure 5A) at Week 4. Differences between GT and vehicle were observed as early as Week 1 and were maintained through Week 4 for both subgroups (Figure 5B). Mean change from Baseline at Week 4 in CDLQI was consistent with that observed for DLQI in GT‐treated patients in the pediatric and older subgroups (−8.1 vs −8.4; Figure 6). Mean decreases in CDLQI and DLQI scores observed for GT‐ vs vehicle‐treated patients in each subgroup indicated a positive impact of GT treatment on health‐related quality of life.

Figure 5.

Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale responder rate (≥ 2‐grade improvement). A, At Week 4. B. To Week 4. Intent‐to‐treat population. P‐values not calculated as these comparisons were post hoc and not designed or powered to detect differences. Multiple imputation (MCMC) was used to impute missing values for Weeks 1‐4. GT, topical glycopyrronium tosylate; MCMC, Markov chain Monte Carlo

Figure 6.

Mean change from Baseline at Week 4 in DLQI or CDLQI. Intent‐to‐treat population. P‐values not calculated as these comparisons were post hoc and not designed or powered to detect differences. No imputation of missing values. BL, baseline; CDLQI, children's DLQI; DLQI, dermatology life quality index; GT, topical glycopyrronium tosylate

3.3. Safety

Pediatric and older subgroups had similar safety profiles (Table 3). Slightly fewer pediatric patients reported TEAEs vs the older subgroup (Table 3). Of two serious TEAEs reported, both occurred in the GT arm of the older subgroup and only one led to discontinuation (moderate unilateral mydriasis; related to treatment). The most frequently reported TEAEs with GT were related to anticholinergic activity and were mild, transient, and infrequently led to study discontinuation. Across subgroups, four patients experienced severe TEAEs; all events occurred in GT treatment groups and were considered related to treatment (pediatric subgroup: one patient with bilateral mydriasis, dry mouth, urinary retention, and anhidrosis [discontinued]; older subgroup: dry mouth [completed]; dry mouth [discontinued]; application site rash [completed]). A slightly greater proportion of GT‐treated pediatric patients reported anticholinergic TEAEs vs GT‐treated older subgroup patients (Table 3); the most frequently reported events were dry mouth and mydriasis in both subgroups. Of eight pediatric patients reporting anticholinergic TEAEs, most experienced ≥ 1 TEAE; all events were considered related to study treatment (Table 4). Most TEAEs in pediatric patients were mild, transient (resolving within approximately 2 weeks regardless of whether study drug was temporarily withheld), reversible, and were managed by temporarily withholding study treatment; TEAEs did not recur upon re‐challenge. One pediatric patient discontinued (5 anticholinergic TEAEs, 4 of which were severe). Study drug was stopped on day of onset, and the TEAEs resolved within a week.

Table 3.

Safety overview and TEAEs

| ≥ 9 to ≤ 16 y | > 16 y | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Vehicle n = 19 | GT n = 25 | Vehicle n = 213 | GT n = 434 |

| Any TEAE | 2 (10.5) | 11 (44.0) | 73 (34.3) | 246 (56.7) |

| Any serious TEAE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.5)a |

| Discontinuations due to TEAE | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 1 (0.5) | 17 (3.9) |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAE by intensity | ||||

| Mild | 2 (10.5) | 6 (24.0) | 51 (23.9) | 164 (37.8) |

| Moderate | 0 | 4 (16.0) | 22 (10.3) | 79 (18.2) |

| Severe | 0 | 1 (4.0)b | 0 | 3 (0.7)c |

| Anticholinergic TEAEs reported in > 2% of patientsd | ||||

| Mydriasis | 0 | 4 (16.0)e | 0 | 27 (6.2)f |

| Vision blurred | 0 | 3 (12.0) | 0 | 13 (3.0) |

| Dry eye | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 1 (0.5) | 10 (2.3) |

| Dry mouth | 0 | 6 (24.0) | 13 (6.1) | 105 (24.2) |

| Urinary hesitation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 (3.7) |

| Urinary retention | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 0 | 6 (1.4) |

| Nasal dryness | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 1 (0.5) | 11 (2.5) |

| Constipation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 (2.1) |

| Non‐anticholinergic TEAEs reported in ≥ 5% of patientsd | ||||

| Nausea | 0 | 2 (8.0) | 0 | 4 (0.9) |

| Application site pain | 1 (5.3) | 2 (8.0) | 21 (9.9) | 38 (8.8) |

| Pain | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Influenza | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 2 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) |

| Headache | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 5 (2.3) | 22 (5.1) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 0 | 2 (8.0) | 3 (1.4) | 24 (5.5) |

| Epistaxis | 0 | 2 (8.0) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) |

Safety population.

Numbers in table represent number of patients reporting ≥ 1 TEAE and not number of events.

GT, topical glycopyrronium tosylate; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

Moderate unilateral mydriasis considered by the Investigator to be related to treatment (discontinued); moderate dehydration considered unrelated to treatment (completed).

Bilateral mydriasis, dry mouth, urinary retention, and anhidrosis (discontinued) considered related to treatment.

Dry mouth (completed); dry mouth (discontinued); application site rash (completed); all events were considered related to treatment.

In either treatment arm in either age subgroup in the pooled population.

One patient reported a unilateral event; two patients reported bilateral events.

Twenty‐two patients reported unilateral events; five patients reported bilateral events.

Table 4.

Summary of anticholinergic TEAEs reported in GT‐treated pediatric patients

| Age/gender | Weighta (kg) | Study outcome | TEAE | Severity | Modification of dose | Resolution | Relationship to treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16/M | 76.7 | Completed | Dry mouth | Mild | No change | Resolved same day without treatmentb | Related |

| 16/F | 74.4 | Completed | Mydriasis (bilateral) | Moderate | Dose on day of onset skipped | Resolved 2 d later without treatment | Relatedc |

| 16/F | 86.2 | Completed | Dry mouth | Mild | No change | Resolved 13 d later without treatment | Related |

| Vision blurred (bilateral) | Mild | Dose skipped 6 d after onset | Resolved 7 d later without treatment | Related | |||

| 15/F | 52.9 | Completed | Dry mouth | Mild | No change | Continued untreated throughout study | Related |

| Mydriasis (bilateral) | Mild | Four doses skipped 6 d after onset | Resolved 8 d later without treatment | Related | |||

| 14/F | 60.9 | Completed | Vision blurred (unilateral) | Moderate | Four doses skipped beginning on day of onset | Resolved 12 d later without treatment | Related |

| Mydriasis (unilateral) | Moderate | Relatedc | |||||

| 14/F | 64.7 | Completed | Dry eye | Mild | No change | Resolved same day without treatment | Related |

| Dry mouth | Mild | Resolved 15 d later without treatment | |||||

| 16/F | 82.6 | Completed | Dry mouth | Moderate | No change | Resolved 9 d later without treatment | Related |

| Nasal dryness | Mild | Resolved 11 d later without treatment | |||||

| 16/M | 71.7 | Discontinued | Vision blurred (bilateral) | Mild | Drug stopped on day of onset | Resolved 2 d later following treatment | Related |

| Mydriasis (bilateral) | Severe | Resolved 2 d later following treatment | |||||

| Dry mouth | Severe | Resolved 3 d later without treatment | |||||

| Urinary retention | Severe | Resolved 4 d later without treatment | |||||

| Anhidrosis | Severe | Resolved 6 d later without treatment |

d, day; F, female; GT, topical glycopyrronium tosylate; M, male; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

Measured at screening.

Patient had six incidences of mild, treatment‐related dry mouth. Five of six incidences resolved the same day without treatment; one of six resolved the following day without treatment.

Bilateral mydriasis is a rare but reported occurrence in the setting of migraine headaches; the patient had a history of migraines and reported a moderate migraine at the time of mydriasis, which resolved at the same time as the TEAE.

Due to inadvertent direct exposure of GT to the eye.

A similar proportion of patients across subgroups and treatment arms experienced LSRs (Table 5). Regardless of subgroup, the majority of GT‐ and vehicle‐treated patients did not experience LSRs; of those that did, most were mild.

Table 5.

Summary of post‐Baseline local skin reactions

| ≥ 9 to ≤ 16 y | > 16 y | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Vehicle n = 19 | GT n = 25 | Vehicle n = 212 | GT n = 429 |

| Any skin reaction | 6 (31.6) | 7 (28.0) | 64 (30.2) | 133 (31.0) |

| Burning/stinging | 2 (10.5) | 2 (8.0) | 37 (17.5) | 62 (14.5) |

| Dryness | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 3 (1.4) | 15 (3.5) |

| Edema | 0 | 0 | 6 (2.8) | 13 (3.0) |

| Erythema | 4 (21.1) | 4 (16.0) | 35 (16.5) | 73 (17.0) |

| Pruritus | 2 (10.5) | 0 | 12 (5.7) | 37 (8.6) |

| Scaling | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 3 (1.4) | 12 (2.8) |

| Any LSR by maximum severity | ||||

| None | 13 (68.4) | 18 (72.0) | 148 (69.8) | 296 (69.0) |

| Mild | 5 (26.3) | 7 (28.0) | 56 (26.4) | 114 (26.6) |

| Moderate | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 6 (2.8) | 18 (4.2) |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) |

Safety population.

A patient is counted as having a local skin reaction if any post‐Baseline assessment is mild, moderate, or severe.

GT, topical glycopyrronium tosylate; LSR, local skin reaction.

4. DISCUSSION

This post hoc analysis is the first to report efficacy and safety data of topical, once‐daily GT in pediatric patients with primary axillary hyperhidrosis. Though a limitation of the trial is the small sample size of the pediatric subgroup, the majority of the assessments showed consistent results between subgroups, and all assessments showed an advantage of GT treatment vs vehicle.

Although large variability was observed with sweat measurements, it is important to note that the episodic nature of sweating can complicate interpretation of gravimetrically measured sweat production.18 Despite this, both groups showed substantially reduced sweat production, and a greater proportion of GT‐ vs vehicle‐treated patients were ASDD/ASDD‐C Item 2 and HDSS responders, indicating that sweating severity decreased by Week 4. Despite limitations in gravimetrically measured sweat production, GT‐treated patients, regardless of age, experienced meaningful reductions in sweating.

These subgroup data are consistent with previous findings of individual and pooled ATMOS‐1 and ATMOS‐2 data showing that GT improved disease symptoms, severity, and quality of life vs vehicle.12, 19 ASDD/ASDD‐C Item 2 responder rates were nearly identical among GT‐treated pediatric and older subgroup patients. Pediatric patients also showed nearly identical responses to the older subgroup in HDSS responder rates and change from Baseline in DLQI/CDLQI. It should be noted that improvements were seen in both treatment arms across the efficacy measures evaluated within these trials. An effect of vehicle comparators has been observed in other dermatology trials,20, 21 which underscore the choice to include a matching vehicle comparator in the ATMOS trials of GT to most accurately assess drug effect in these trials. The GT towelette contains the following excipients: citric acid, dehydrated alcohol, purified water, and sodium citrate.22 Identical excipients were included in the vehicle comparator of the ATMOS trials to account for any potential effect due to a compound other than active drug. Though a vehicle effect was observed in these trials, GT‐treated patients had a significantly greater response than that observed with vehicle.12, 19

Glycopyrronium tosylate was generally well tolerated, and TEAEs in pediatric patients were qualitatively similar to those seen in the older subgroup and consistent with those expected with anticholinergics. Unlike mydriasis events in the older subgroup, which were largely unilateral (22 of 27 events), the majority in the pediatric subgroup were bilateral (3 of 4 events). Although difficult to determine given the small number of events, this may be attributed to pediatric patients being more likely to touch both eyes after GT application or possibly anticholinergic effects resultant from systemic exposure, which are minimized but not eliminated completely by topical GT application. Even so, most patients completed the study. Overall, in both subgroups, most anticholinergic TEAEs were mild, transient, infrequently led to discontinuation, and did not recur with re‐challenge. The majority of patients did not experience LSRs; most LSRs that were reported were mild in intensity.

A limitation of these studies is the relatively short duration compared to the chronic nature of primary hyperhidrosis. Results from the long‐term open‐label extension of these trials have been reported, and safety findings from the pediatric subgroup are consistent with the results provided here from the double‐blind trials.23, 24

Despite therapeutic options for axillary hyperhidrosis, patients generally remain dissatisfied with treatment.6, 25 GT was FDA‐approved in June 2018 for patients ≥ 9 years with primary axillary hyperhidrosis, representing the first approved treatment to include pediatric patients. For adults, this represents a second approved therapy in addition to onabotulinum toxinA;26 a microwave device for sweat gland ablation27 has also been cleared for use in adults. Oral anticholinergics are used off‐label even though side effects remain a challenge. In a retrospective study of the oral anticholinergic glycopyrrolate in pediatric patients, the most highly cited reason for interrupting therapy was being bothered by side effects (62%).28 Topical administration can reduce overall drug exposure and may mitigate adverse event risk.29 Pharmacokinetic data show that maximum plasma concentration with topical GT once‐daily for 5 days was low and comparable between children and adults (C max = 0.07 ± 0.06 ng/mL in children age 10‐17 years and C max = 0.08 ± 0.04 ng/mL for adults).22 C max values for topical GT were lower than values reported in the literature for oral anticholinergics, though the potential for some systemic exposure with topical GT cannot be excluded.30, 31

A recent publication summarized favorable results on hyperhidrosis severity and quality of life in adolescents/young adults with topical administration of the anticholinergic oxybutynin, though this was a small (N = 10), uncontrolled pilot study.32 The unmet need for new therapies may be addressed with GT, which in this analysis mitigated disease severity while improving quality of life in pediatric patients, with a favorable safety profile. Additional trials that prospectively include pediatric patients with primary axillary hyperhidrosis are needed to confirm and expand the findings described here.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Hebert is a consultant for Dermira, Inc., and an employee of the UTHealth McGovern Medical School, Houston, which received compensation from Dermira, Inc., for study participation. Dr. Glaser is a consultant for Dermira, Inc., and an investigator for Allergan; Atacama Therapeutics; Brickell Biotech, Inc.; Galderma; and Revance Therapeutics, Inc. She has received honoraria for consulting with Allergan and Dermira, Inc. Dr. Green is an investigator for Brickell Biotech, Inc., and an advisory board member and investigator for Dermira, Inc. Dr. Werschler is a consultant and investigator for Dermira, Inc. Dr. Forsha is an investigator for Jordan Valley Dermatology and Research Center. Ms. Drew and Dr. Gopalan are employees of Dermira, Inc. Dr. Pariser received honoraria for consulting for Atacama Therapeutics; Brickell Biotech, Inc.; Biofrontera AG; Celgene Corporation; Dermira, Inc.; DUSA Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; LEO Pharma, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Promius Pharma; LLC; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Sanofi; TDM SurgiTech, Inc.; TheraVida, Inc.; and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. He received honoraria for advisory board participation for Pfizer, Inc. He received grants/research funding for serving as an investigator for Abbott Laboratories; Amgen, Inc.; Asana BioSciences; LLC; Brickell Biotech Inc.; Celgene Corporation; Dermavant Sciences, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; LEO Pharma, Inc.; Merck & Company, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Novo Nordisk A/S; Ortho Dermatologics, Inc.; Peplin, Inc.; Photocure ASA; Promius Pharma; LLC; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Stiefel Laboratories; and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. He received honoraria for serving as an investigator for LEO Pharma, Inc., and Pfizer, Inc.

STATEMENT OF APPROPRIATE IRB APPROVAL AND INFORMED CONSENT

The studies reported on herein were approved by institutional review boards.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support for this manuscript was provided by Ashley A. Skorusa, PhD, of Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, IL), with financial support from Dermira, Inc.

Hebert AA, Glaser DA, Green L, et al. Glycopyrronium tosylate in pediatric primary axillary hyperhidrosis: Post hoc analysis of efficacy and safety findings by age from two phase three randomized controlled trials. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:89‐99. 10.1111/pde.13723

Funding information

These studies are sponsored and funded by Dermira, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1. Doolittle J, Walker P, Mills T, Thurston J. Hyperhidrosis: an update on prevalence and severity in the United States. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308(10):743‐749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grabell DA, Hebert AA. Current and emerging medical therapies for primary hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7(1):25‐36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hebert A, Glaser DA, Ballard A, Pieretti L, de Trindade Almeida A, Pariser D. Prevalence of primary focal hyperhidrosis (PFHh) among teens 12‐17 in U.S. Population. Oral (Late‐Breaker) presented at 75th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; 2017; Orlando, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amir M, Arish A, Weinstein Y, Pfeffer M, Levy Y. Impairment in quality of life among patients seeking surgery for hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating): preliminary results. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2000;37(1):25‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cina CS, Clase CM. The Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale: a measure of severity in individuals with hyperhidrosis. Qual Life Res. 1999;8(8):693‐698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Strutton DR, Kowalski JW, Glaser DA, Stang PE. U.S. prevalence of hyperhidrosis and impact on individuals with axillary hyperhidrosis: results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(2):241‐248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mirkovic SE, Rystedt A, Balling M, Swartling C. Hyperhidrosis substantially reduces quality of life in children: a retrospective study describing symptoms, consequences and treatment with Botulinum Toxin. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(1):103‐107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Naumann M, Hamm H, Spalding JR, Kowalski J, Lee J. Comparing the quality of life effects of primary focal hyperhidrosis to other dermatological conditions as assessed by the dermatology life quality index (DLQI). Val Health. 2003;6(3):242. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bohaty BR, Hebert AA. Special considerations for children with hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32(4):477‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gelbard CM, Epstein H, Hebert A. Primary pediatric hyperhidrosis: a review of current treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(6):591‐598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alvarez MA, Ruano J, Gomez FJ, et al. Differences between objective efficacy and perceived efficacy in patients with palmar hyperhidrosis treated with either botulinum toxin or endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(3):e282‐e288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Glaser DA, Hebert AA, Nast A, et al. Topical glycopyrronium tosylate for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis: results from the ATMOS‐1 and ATMOS‐2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Glaser D, Hebert A, Fehnel S, et al. The axillary sweating daily diary: A validated patient‐reported outcome measure to assess axillary hyperhidrosis symptom severity. Poster presented at 13th Annual Maui Derm for Dermatologists, 2017, Maui, HI. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nelson L, Dibenedetti D, Pariser D, et al. Development and validation of the Axillary Sweating Daily Diary: a patient‐reported outcome measure to assess sweating severity. J Pat Rep Outcome. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guidance for Industry: Patient‐Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. In: U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA); 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Solish N, Bertucci V, Dansereau A, et al. A comprehensive approach to the recognition, diagnosis, and severity‐based treatment of focal hyperhidrosis: recommendations of the Canadian Hyperhidrosis Advisory Committee. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(8):908‐923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brandt M, Bielfeldt S, Springmann G, Wilhelm KP. Influence of climatic conditions on antiperspirant efficacy determined at different test areas. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14(2):213‐219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pariser DM, Hebert AA, Drew J, Quiring J, Gopalan R, Glaser DA. Topical glycopyrronium tosylate for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis: patient reported outcomes from the ATMOS‐1 and ATMOS‐2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. (In press, https://rd.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40257-018-0395-0). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chiou WL. Low intrinsic drug activity and dominant vehicle (placebo) effect in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;50(6):434‐437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lamel SA, Myer KA, Younes N, Zhou JA, Maibach H, Maibach HI. Placebo response in relation to clinical trial design: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials for determining biologic efficacy in psoriasis treatment. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304(9):707‐717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. QBREXZA™ (glycopyrronium) cloth, 2.4%, for topical use. Prescribing Information. Dermira, Inc., Menlo Park, CA: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Glaser DA, Hebert AA, Nast A, et al. Open‐label study (ARIDO) evaluating long‐term safety of topical glycopyrronium tosylate (GT) in patients with primary axillary hyperhidrosis. Poster presentation presented at 35th Annual Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference, 2017, Las Vegas, NV. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hebert AA, Glaser DA, Green L, et al. Short‐ and Long‐Term Efficacy and Safety of Glycopyrronium Tosylate for the Treatment of Primary Axillary Hyperhidrosis: Post Hoc Pediatric Subgroup Analyses from the Phase 3 Studies. Paper presented at: 27th International Congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; September 12‐16, 2018, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Glaser DA, Hebert A, Pieretti L, Pariser D. Understanding patient experience with hyperhidrosis: a national survey of 1,985 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(4):392‐396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. BOTOX (onabotulinumtoxinA) for injection, for intramuscular, intradetrusor, or intradermal use. Prescribing Information. Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27. miraDry System [510(k)]. Miramar Labs, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Diaz L, Bicknell L, McNiece K, Schmidtberger R, Hebert A. Efficacy and compliance of oral glycopyrrolate in the treatment of primary hyperhidrosis in pediatric patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;302013:633‐634. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Staskin DR. Transdermal systems for overactive bladder: principles and practice. Rev Urol. 2003;5(suppl 8):S26‐S30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rautakorpi P, Manner T, Ali‐Melkkila T, Kaila T, Olkkola K, Kanto J. Pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of glycopyrrolate in children. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;83(3):132‐134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. CUVPOSA® (glycopyrrolate) Oral Solution . Prescribing Information. Raleigh, NC: Merz Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nguyen NV, Gralla J, Abbott J, Bruckner AL. Oxybutynin 3% gel for the treatment of primary focal hyperhidrosis in adolescents and young adults. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(2):208‐212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]