Abstract

Background

There are scarce data in Scandinavia about treatment satisfaction among patients with psoriasis (PsO) and/or psoriatic arthritis (PsA). The number of patients receiving systemic treatment is unknown.

Objective

To describe patients’ experience of treatments for PsO/PsA in Sweden, Denmark and Norway, addressing communication with physicians, satisfaction with treatment and concerns regarding treatment options.

Methods

The NORdic PAtient survey of Psoriasis and Psoriatic arthritis (NORPAPP) asked 22 050 adults (randomly selected from the YouGov panels in Sweden, Denmark and Norway) whether they had PsO/PsA. A total of 1264 individuals who reported physician‐diagnosed PsO/PsA were invited to participate in the full survey; 96.6% responded positively.

Results

Systemic treatment use was reported by 14.6% (biologic: 8.1%) of respondents with PsO only and by 58.5% (biologic: 31.8%) of respondents with PsA. Biologic treatments were more frequently reported by respondents considering their disease severe (26.8% vs 6.7% non‐severe) and those who were members of patient organizations (40.7% vs 6.9% non‐members). Discussing systemic treatments with their physician was reported significantly more frequently by respondents with PsA, those perceiving their disease as severe (although 35.2% had never discussed systemic treatment with their physician) and those reporting being a member of a patient organization (P < 0.05). Many respondents reported health risk concerns and dissatisfaction with their treatment. Of special interest was that respondents aged 45–75 years reported less experience with biologics (8.1%) than those aged 18–44 years (21.5%). The older respondents also reported more uncertainty regarding long‐term health risks related to systemic treatments (most [66.7–72.9%] responded ‘do not know’ when asked about the risk of systemic options).

Conclusion

It appears likely that substantial numbers of Scandinavians suffering from severe PsO/PsA are not receiving optimal treatment from a patient perspective, particularly older patients. Also, one‐third of respondents with severe symptoms had never discussed systemic treatment with a physician.

Introduction

Psoriasis (PsO) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease associated with significant physical and psychosocial burden. The global prevalence of PsO in adults is around 3%; however, estimates from studies in Norway, Sweden and Denmark are consistent with a relatively high prevalence in the Scandinavian region (3.9–11.5%).1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Up to 35% of individuals with PsO will develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which is associated with decreased physical function, increased comorbidities and a substantial reduction in quality of life.6, 7, 8 PsO and PsA disease management requires lifelong treatment, which can itself impose additional clinical and psychological burdens. Therapeutic approaches include topical treatments and phototherapy for milder forms of PsO on the skin and scalp and systemic treatments, which are recommended for more severe manifestations.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Traditional oral systemic therapies such as methotrexate, acitretin and cyclosporine have been available for many years, but their effective use can be hindered by patient intolerance and organ‐specific toxicities.12, 14 Several subcutaneously and intravenously administered biologics targeting cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of PsO and PsA have recently been approved.15 These agents are usually recommended for use after failure of conventional systemic therapy.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 17 Despite the availability of several options for systemic treatment of PsO and PsA, and published guidelines recommending their use in patients with severe symptoms,11, 12, 13 some studies suggest that many patients remain undertreated or unsatisfied with their treatment.18, 19, 20, 21 The largest global probability survey to be conducted with patients suffering from PsO and PsA, the Multinational Assessment of PsO and PsA (MAPP), highlighted that although treatment satisfaction was fairly high among those with non‐severe symptoms, many of those with severe disease were undertreated; for example, >80% of patients with an affected body surface area ≥4 palms were receiving no treatment or topical therapy alone and 60% of patients with PsA were not being treated for their joint disease.20 Other studies have also shown low levels of treatment satisfaction and a lack of systemic treatment use among patients with severe psoriasis.18, 22

The MAPP survey excluded Scandinavian countries; therefore, the NORPAPP was conducted to gain a better understanding of the treatment of PsO and PsA in Sweden, Denmark and Norway. The purpose of this study was to provide some insight into the main challenges faced by people living with PsO and PsA in these countries and to understand patients’ perspectives on communication with the healthcare system and the different treatments prescribed. In this report, we focus on respondent's perspectives on, and satisfaction with, the different available treatments for PsO and PsA.

Materials and methods

YouGov (an international Internet‐based market research firm) conducted the survey during November and December 2015 in Sweden, Denmark and Norway following the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC)/European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR) International Code on Market, Opinion and Social Research and Data Analytics, as previously described.2 The survey was conducted in accordance with ethical standards required in each participating country. In brief, 22 050 adults (aged 18–74 years) from the YouGov panels were asked whether they had any type of PsO or PsA. Active sampling was used to ensure that this initial survey population was representative of the adult population in each country in terms of age and gender. All 1264 individuals who reported physician‐diagnosed PsO or PsA were invited to participate in the full survey, which was completed via an online link sent by email, and the response rate was 96.6% (1221 respondents). The questions explored in this paper addressed: patterns of treatment use, whether or not systemic treatments (including biologics) had been discussed with a physician, perceptions of the long‐term health risk of treatments, and satisfaction with systemic treatments with a specific focus on methotrexate and biologics (Appendix).

Respondent data were weighted to match the demographics (gender and age) of each country. Significant deviations in responses between subgroups based on country, diagnoses, age, perceived severity of their condition, patient organization membership and frequency of physician contact were assessed using chi‐squared tests and z‐tests with Bonferroni corrections (total α = 0.05) for comparisons of multiple answers within each question. Since the NORPAPP was designed to investigate patients’ perspectives, a subjective measure was used to define subgroups based on severity. Respondents were asked how they would rate the severity of their condition over the past 12 months and were then grouped into those who perceived their disease to be severe (responding ‘quite severe’, ‘very severe’ or ‘extremely severe’) and those who perceived their disease to be non‐severe (responding ‘not particularly severe’ or ‘not severe at all’).

Results

Study population

Population demographics have been reported previously.2 There were approximately equal proportions of males (48.9%) and females (51.1%), and just over half of the respondents were in the older age group (55.1% aged 45–74 vs 44.9% aged 18–44). About three‐quarters of the respondents (74.6%) were diagnosed with PsO alone, and in the remaining quarter, respondents were diagnosed with PsA alone (15.1%) or PsA with PsO (10.3%). Most respondents (72.7%) with PsO alone considered their condition to be non‐severe; 26.9% considered their condition to be severe.2 Fewer respondents reporting PsA with or without PsO (PsA ± PsO) considered their condition to be non‐severe (38.9%); 58.7% considered their condition to be severe. Overall, 10.7% of those reporting PsO alone had never seen a dermatologist and 14.3% of those reporting PsA ± PsO had never seen a rheumatologist.2

Treatment

Patterns of treatment use

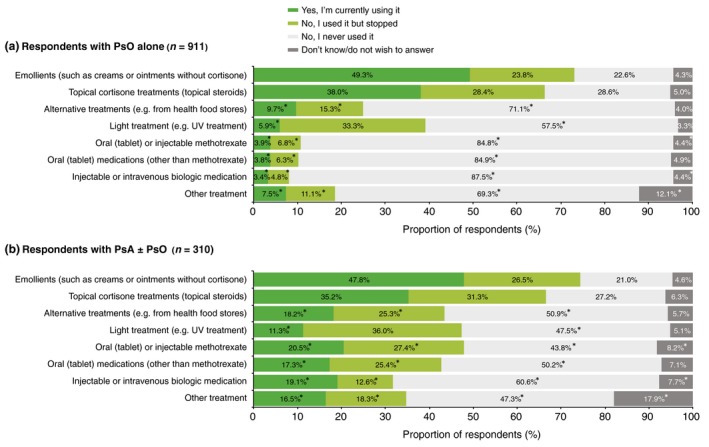

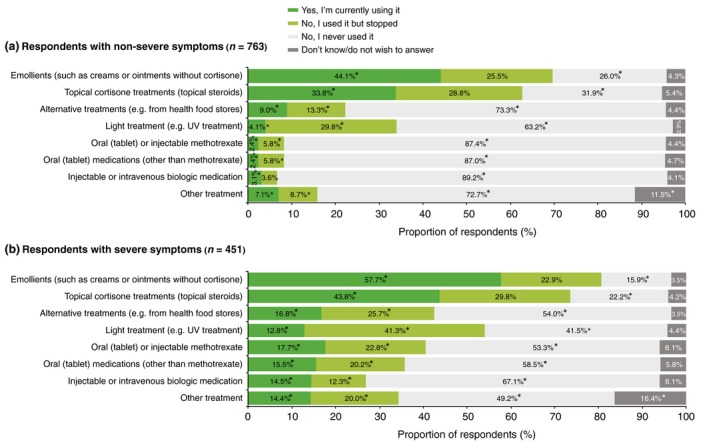

Diagnosis (PsO alone vs PsA ± PsO) did not affect the proportion of respondents who used or had tried emollients and topical cortisones, which were the most commonly used treatments for both groups (Fig. 1). All other treatments (alternative therapies, light treatment, oral or injectable methotrexate, other oral medications, injectable or intravenous biologics or ‘other treatment’) were significantly more likely to have been used, or tried and discontinued, by respondents with PsA ± PsO (Fig. 1). Respondents who described their symptoms as severe were significantly more likely to have used all treatments and at least three times more likely to have used, or tried, systemic treatments than those who described their symptoms as non‐severe (Fig. 2). Systemic treatments of any kind were used, or tried, by 14.6% of respondents with PsO alone and by 58.5% of respondents with PsA ± PsO.

Figure 1.

Patterns of treatment use reported by respondents with (a) psoriasis (PsO) alone and (b) psoriatic arthritis (PsA) with or without PsO. *Significant difference between diagnostic groups (a) and (b) (Bonferroni‐corrected z‐tests, total α = 0.05). UV, ultraviolet.

Figure 2.

Patterns of treatment use reported by respondents who perceive their symptoms to be (a) non‐severe and (b) severe. *Significant difference between symptom severity groups (a) and (b) (Bonferroni‐corrected z‐tests, total α = 0.05). UV, ultraviolet.

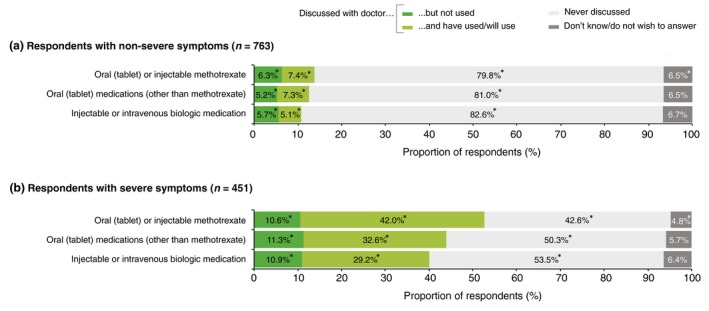

Systemic treatments discussed with a physician

Respondents who described their symptoms as severe were more than three times as likely to have discussed systemic treatments with their physician and more than four times as likely to have used, or intended to use, systemic treatments than those who described their symptoms as non‐severe (Fig. 3). However, over one‐third of respondents (35.2%) with severe symptoms had never discussed a systemic treatment with their physician.

Figure 3.

Systemic treatments that were discussed with a doctor by respondents who perceive their symptoms to be (a) non‐severe and (b) severe. *Significant difference between symptom severity groups (a) and (b) (Bonferroni‐corrected z‐tests, total α = 0.05).

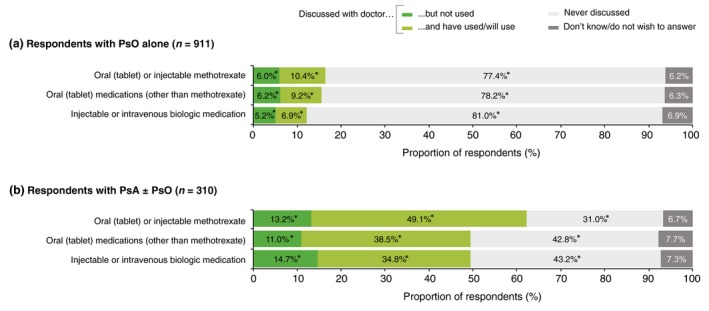

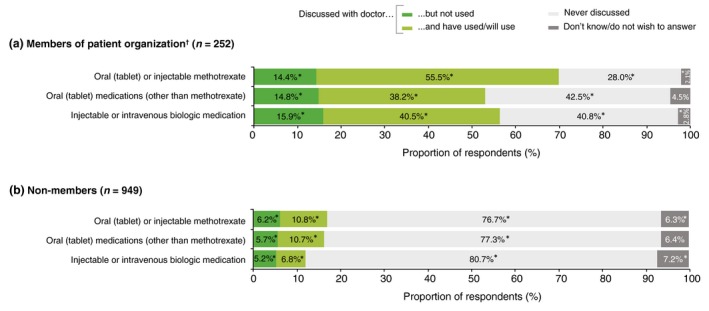

Respondents with PsA ± PsO were significantly and substantially more likely to have discussed systemic treatments with their physician and to have used, or intended to use, such treatments than respondents with PsO alone (Fig. 4). Membership of a patient organization had a similar effect; respondents who were members were significantly and substantially more likely to have discussed systemic treatments, and to have used or intended to use them, than non‐members (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Systemic treatments that were discussed with a physician by respondents with (a) psoriasis (PsO) alone and (b) psoriatic arthritis (PsA) with or without PsO. *Significant difference between diagnostic groups (a) and (b) (Bonferroni‐corrected z‐tests, total α = 0.05).

Figure 5.

Systemic treatments that were discussed with a doctor by respondents, split by membership of a patient organization: (a) members and (b) non‐members. *Significant difference between membership groups (a) and (b) (Bonferroni‐corrected z‐tests, total α = 0.05). †Membership of a patient organization was indicated by 21.0% of respondents; of these, 52.3% had PsO alone (representing 14.6% of all respondents with PsO alone) and 47.7% had PsA with or without PsO (representing 46.5% of all respondents with PsA alone and 35.3% of those with both conditions).

Use of biologics

Respondents who reported having used biologics (n = 173) included a significantly higher proportion of those with PsA ± PsO than with PsO alone (31.8% vs 8.1%, P < 0.05). Respondents who considered their symptoms to be severe had used biologics significantly more often than those who considered their symptoms to be non‐severe (26.8% vs 6.7%, P < 0.05). The use of biologics was significantly and strongly linked to membership of a patient organization; 40.7% of respondents who were organization members had used biologics compared with 6.9% of respondents who were not (P < 0.05). There was also a significant link with age group; biologics had been used by 21.5% of respondents aged 18–44 years and by 8.1% of respondents aged 45–74 years (P < 0.05). No significant gender differences were observed.

Respondents who had used biologics were asked whether the suggestion to use them originally came from themselves or their physician; 35.5% had initiated treatment with biologics at the suggestion of their physician, 29.8% made the suggestion themselves, and in 23.2% of cases, the suggestion came from both themselves and their physician. Respondents aged 45–74 years were least likely to have suggested biologics themselves (14.4%) and were most likely to have started treatment with biologics at the suggestion of their physician (53.8%). Respondents aged 18–44 years were most likely to have suggested biologics themselves (36.9%, significantly more likely than those aged 45–74 years, P < 0.05) and less likely to have started treatment based on their physician's recommendation (27.0%, significantly less likely than those aged 45–74 years, P < 0.05). There was no significant association between the source of the suggestion to use biologics and membership of a patient organization, severity, gender or diagnosis.

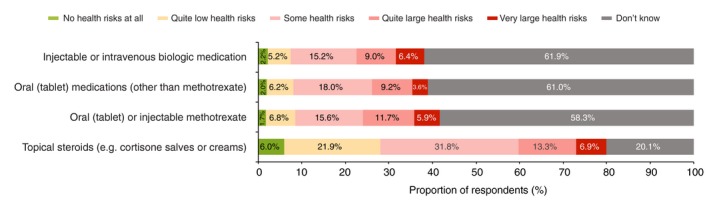

Respondent perceptions of long‐term health risks of treatments

When asked about the health risks of treatments, approximately half of the respondents thought there was a least ‘some health risk’ for topical steroids, whereas only about one‐third noted at least ‘some health risk’ for systemic treatments (Fig. 6). Although most respondents (79.9%) felt able to comment on the safety of topical steroids, 58.3–61.9% responded ‘don't know’ when asked about the safety of systemic treatments. A significantly (P < 0.05) lower proportion of respondents aged 18–44 years (47.7–49.1%) responded ‘don't know’ than those aged 45–74 (66.7–72.9%). The most influential factor in the respondents’ ability to comment on the safety of systemic treatments was membership of a patient organization; less than one‐third (26.1–30.7%) of respondents who were members answered ‘don't know’, significantly less than the approximately two‐thirds (66.8–70.4%) who were not members (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Respondent perceptions of long‐term medication safety (n = 1221).

Respondent satisfaction with systemic treatments

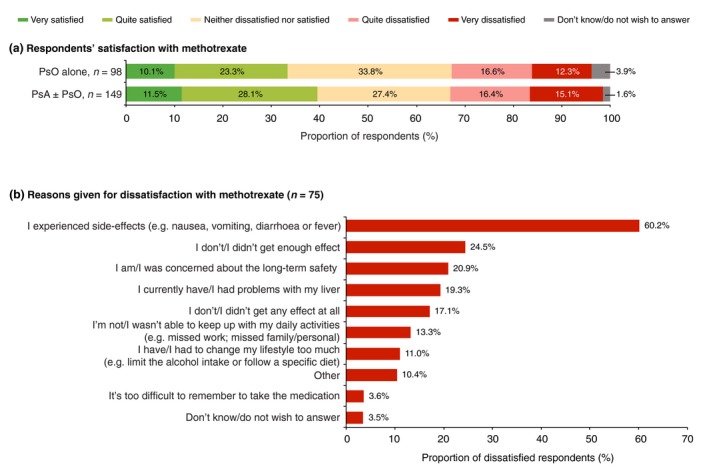

Methotrexate

Respondents using methotrexate, either oral or injectable, were satisfied (‘very satisfied’ or ‘quite satisfied’), indifferent (‘neither satisfied or dissatisfied’) or dissatisfied (‘very dissatisfied or ‘quite dissatisfied’) with the treatment in approximately equal measure (Fig. 7a). There was no significant difference in respondents’ satisfaction between those with PsA ± PsO and those with PsO alone. Respondents aged 45–74 years were significantly (P < 0.05) less likely to be indifferent (22.7% vs 35.9%) and more likely to be ‘very dissatisfied’ (22.0% vs 7.4%) or ‘very satisfied’ (15.5% vs 7.2%) than those aged 18–44 years. Respondents who were members of patient organizations were significantly (P < 0.05) less likely to be ‘very dissatisfied’ (7.6% vs 20.3%) and more likely to be ‘quite satisfied’ (32.0% vs 19.3%) than non‐members.

Figure 7.

(a) Respondent satisfaction with oral or injectable methotrexate (n = 247), split by diagnosis of psoriasis (PsO) alone versus psoriatic arthritis (PsA) with or without PsO and (b) reasons for dissatisfaction (multiple answers were allowed).

Overall, 30.5% of the respondents using methotrexate were dissatisfied with the treatment. A majority of the very/quite dissatisfied respondents reported side‐effects as a reason for their dissatisfaction (Fig. 7b). Other frequently cited reasons for dissatisfaction were concerns about safety and lack of efficacy (Fig. 7b).

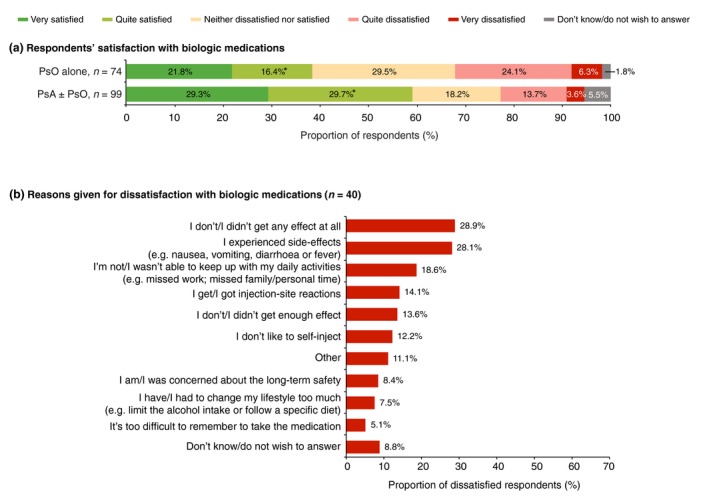

Biologics

Respondent satisfaction with biologics varied by diagnosis – a significantly higher proportion of respondents with PsA ± PsO were ‘quite satisfied’ compared with those with PsO alone (Fig. 8a). Other differences were not statistically significant, but there was a trend towards greater satisfaction and lower dissatisfaction among respondents with PsA ± PsO versus those with PsO alone (Fig. 8a). Overall, 22.9% of respondents were dissatisfied with biologics. The most frequently reported reasons for dissatisfaction with biologics were a lack of efficacy and the side‐effects (Fig. 8b).

Figure 8.

(a) Respondent satisfaction with biologic medications (n = 173), split by diagnosis of psoriasis (PsO) alone versus psoriatic arthritis (PsA) with or without PsO and (b) reasons for dissatisfaction (multiple answers were allowed). *Significant difference between diagnostic groups (Bonferroni‐corrected z‐tests, total α = 0.05).

Discussion

The finding that 35.2% of respondents with self‐perceived severe symptoms had not discussed systemic treatment with their physician suggests that there are still too many patients in Scandinavia not receiving adequate treatment for PsO and/or PsA. Current or prior use of systemic therapy was reported by 14% of respondents with PsO alone. Although low, this proportion is comparable with the proportion that was reported in the MAPP study (7–14%, depending on severity).20 As expected, a greater proportion of respondents with PsA, who generally had more severe symptoms, reported using systemic treatments of any kind (58.5%) and biologic treatments (31.8%). These figures are higher than the MAPP study in which only 19% of respondents with PsA reported receiving conventional oral therapy alone and 14% reported receiving biologic treatments. However, the MAPP study included an unmatched, parallel survey of dermatologists and rheumatologists who reported the prescription of systemic treatment at higher rates than indicated by surveyed patients: dermatologists prescribed conventional oral therapies for 11.4% of patients with PsO and biologics for 11.4%; rheumatologists prescribed conventional oral therapies for 40.6% of patients with PsA and dermatologists prescribed for 22.5%; biologics were prescribed by rheumatologists for 21.4% of patients and by dermatologists for 19.6%.23 Differences between these physician‐reported levels of treatment in the MAPP study and levels of treatment reported by patients in both the MAPP study and the NORPAPP may reflect the high proportion of patients who were not regularly followed by a physician.

The differences between the NORPAPP and the MAPP study in terms of the proportion of patients reporting receiving treatment, may reflect regional differences or changes in clinical practice over time. The use of systemic therapy in Germany increased following the introduction of the National Goals for Healthcare in Psoriasis (2010–2015) and implementation of the first European S3‐Guidelines in 2012.12, 24, 25 In 2013/2014, an estimated 59.5% of patients with PsO had received systemic therapy at least once within the previous 5 years compared with 47.3% in 2007 and 32.9% in 2005.7, 25 Since then, with the WHO resolution on PsO and the publication of updated European S3‐Guidelines in 2015,12 it is possible that the treatment of PsO and PsA is also beginning to improve in other countries.

A factor that may have had an impact on the prescription and use of systematic treatments is patient preference. Respondents who were members of patient organizations were more likely to discuss systemic therapy with their physician and to have systemic treatment prescribed. It appears that well‐informed respondents received more adequate treatment, although the risk of ‘over‐treatment’ cannot be assessed. Compared with those aged 18–44 years, respondents aged 45–74 years were less likely to have suggested biologics to their physician and were less likely to have them prescribed, which may be linked. This implies that a lack of information on newer treatments may be an issue for both patients and physicians. The supposition of underinformed physicians is made more plausible by the fact that many respondents saw general practitioners (GPs) rather than specialists. In Norway, it is strongly recommended that treatment with methotrexate or cyclosporine is initiated by a specialist and that the prescription of biologics is regulated by hospital dermatology committees. In Sweden, although there is no formal restriction for GPs or other physicians to prescribe systemic medication, in practice, only dermatologists prescribe these treatments.

Levels of dissatisfaction with systemic treatments appeared to be quite high with 30.5% of respondents indicating dissatisfaction with methotrexate, mostly citing side‐effects as the reason. These results are largely comparable with the MAPP study, in which approximately half of the patients indicated that they found systemic treatment with oral agents to be burdensome, mostly because of fears about side‐effects.20, 26 For biologics, 22.9% of respondents indicated dissatisfaction, with a lack of efficacy and the side‐effects being the most frequently cited reasons. There was a trend towards greater satisfaction among respondents with PsA than among those with PsO alone, but there are no obvious reasons for this difference.

Level of knowledge and expectations could have played a role in the level of treatment satisfaction. Although respondents who were members of patient organizations were more burdened by their disease (unublished data), they had greater levels of satisfaction with methotrexate treatment than non‐members. We hypothesize that well‐informed patients are more aware of what to expect from treatment. Respondents aged 45–74 years were less satisfied than those aged 18–44 years, so it may be that older respondents were less well‐informed of the benefits and side‐effects of treatment. This assumption is supported by the older age‐group's larger fraction of ‘don't know’ answers to the questions regarding systemic medication safety.

The results of the NORPAPP should be interpreted within the context of its limitations. As with all retrospective surveys, the data rely on the accurate recall of facts and interpretation of questions by respondents. A strength of the survey is that, like the MAPP study, participants were not identified based on membership of patient organizations but were more broadly representative of the cross‐section of individuals living with PsO and PsA in Sweden, Denmark and Norway. Nevertheless, 21% of respondents were members of patient organizations and this could reflect the level of engagement of individuals in the YouGov panels, which are made up of individuals who have specifically opted in to participate in online studies. Given the differences observed between respondents who are members of patient organizations and those who are not, this factor should be considered when interpreting the survey results. Although the survey was conducted in three different countries, data were pooled to provide a large patient group, which allowed for broader subgroup analyses. The justification for this is that Sweden, Denmark and Norway have a similar prevalence of PsO and PsA,3, 4, 5 and have largely similar healthcare systems and access to treatment (including biologics).27, 28

In conclusion, the results of this survey from Scandinavia strongly support the findings from studies carried out in other European countries and in the United States that patients with PsO and/or PsA are often dissatisfied with the treatment they receive. We also confirmed that few patients, even if they have a serious disease, receive systemic treatment. It appears likely that substantial numbers of Scandinavians who perceive their PsO and/or PsA to be severe are not receiving optimal treatment, particularly those aged 45–74 years. Over one‐third of respondents who perceived their symptoms to be severe had never discussed systemic treatment with a physician. Future studies should assess whether better communication and an increased awareness of available treatment options, among both patients and treating physicians, can help to improve access to appropriate treatments in the Scandinavian population suffering from severe PsO and/or PsA.

Full questionnaire

Note that only those questions relevant to each individual were presented to them.

Question 1: Do you have any type of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis?

Yes, and I'm diagnosed by a physician

Yes, but I'm not diagnosed by a physician

No, I do not have any type of psoriasis

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 2: Which type of psoriasis have you been diagnosed with by a physician?

Psoriasis on the skin, on nails or the scalp

Psoriatic arthritis

Both psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp) and psoriatic arthritis

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 3: How long after your first symptoms were you diagnosed by a physician?

Separate answers for ‘Psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp)’ and ‘Psoriatic arthritis’

Within one year

One year after

2–4 years after

5–9 years after

10–14 years after

15–19 years after

20–29 years after

30 years after or more

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 4: If you think about the past 12 months, how would you rate the severity of your … ?

Separate answers for ‘Psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp)’ and ‘Psoriatic arthritis’

Not severe at all

Not particularly severe

Quite severe

Very severe

Extremely severe

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 5: Please describe in which way your psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp) is quite, very or extremely severe

Free text answer

Question 6: Please describe in which way your psoriatic arthritis is quite, very or extremely severe

Free text answer

Question 7: Which symptoms or troubles due to your psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp) have you experienced in the past 12 months?

Bleeding

Burning

Depression or anxiety

Fatigue

Flaking/scales

Itching

Pain

Plaque

Pustules (pus‐filled blisters)

Redness

Swollen fingers or toes (e.g. sausage digits, so called dactylitis)

Tender or swollen tendons (e.g. on the heal, so called enthesitis)

Nail psoriasis

Other symptoms

I have not experienced any symptoms in the past 12 months

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 8: Where on the body have you had symptoms of psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp) in the past 12 months?

Ankles

Arm pit

Back/spine

Chest

Elbow

Fingers

Genitals

Heels

Hips

In skin folds (inverse psoriasis)

Knees

Nails

Neck

Scalp

Shoulders

The bend of the arm

Palm of hands or sole of feet

Toes

Ears

Wrist

Other body location

I have not experienced any symptoms in the past 12 months

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 9: Based on the amount of psoriasis that could be covered by the palm of your hand, about how many palms would you say that you currently have across your entire body?

None

Less than 1 palm

1–3 palms

4–9 palms

10–19 palms

20 palms or more

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 10: How often have you had relapses or flare‐ups of your psoriasis (on the skin, nails or scalp) in the past three years? With relapse or flare‐up, we mean periods when symptoms have worsened.

I've had constant symptoms, with no remission

Every week

Every month

Every quarter

Every six months

Every year

Every two years

Every three years (once in the past three years)

I haven't had any flare‐up or relapses in the past three years

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 11: Have you experienced pain or soreness in any of your joints?

Yes

Yes, I have it currently

Yes, in the past 12 months

Yes, more than one year ago

No, never

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 12: In which location is/were your joint pain or soreness most bothersome?

Ankles

Back/spine

Elbow

Fingers/hands

Heel

Sole of foot

Hips

Knees

Neck

Shoulders

Toes

Wrist

Other body location

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 13: To what extent do you agree that you have experienced the following in the past 12 months due to your psoriasis?

Each statement scored from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (totally agree)

I've felt embarrassed or self‐conscious because of my skin symptoms

The topical treatment (such as ointments or creams) of my skin has been taking up too much time

The topical treatment (such as ointments or creams) of my skin has been inconvenient or messy

Question 14: To which extent do you agree that you have experienced the following in the past 12 months due to your psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis?

Each statement scored from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (totally agree)

My disease has …

… caused sleeping disorders/lack of sleep

… prevented me from maintaining good hygiene (e.g. showering or brushing the teeth)

… interfered with my daily routines such as getting out of bed, eating, cleaning, shopping or cooking

… prevented me from wearing specific clothes/shoes

… prevented me from participating in a social activity

… prevented me from doing sports or a leisure activity

… made me feel depressed or anxious

… prevented me from having an active sex life

… created difficulties in the relationship with my partner, family, close friends or relative

… created difficulties in the relationship with acquaintances such as new friends or colleagues

Question 15: Have you experienced any trouble doing different activities in the past 12 months due to your psoriatic arthritis?

Yes, getting dressed, including tying shoelaces and doing buttons

Yes, getting in and out of bed

Yes, lifting a full cup or glass to my mouth

Yes, walking outdoors on flat ground

Yes, washing and drying my body

Yes, bending down to pick up something up from the floor

Yes, turning faucets on and off

Yes, getting in and out of a car

Yes, having sex

Yes, other difficulties, what? – Free text answer

No, I haven't had any trouble

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 16: Have you been absent from work or school in the past 12 months due to your psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis?

Yes, I've been on a long‐term sick leave

Yes, a couple of days per week

Yes, a couple of days per month

Yes, a couple of days in the past year

Yes, only once in the past 12 months

No

I did not work or go to school in the past 12 months

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 17: To what extent has your psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis had a negative impact on your work/career or education since you first developed symptoms?

No impact at all

Quite low impact

Impact

Question 18: Which types of healthcare professionals have you seen in the past three years for your … ?

Separate answers for ‘Psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp)’ and ‘Psoriatic arthritis’

Allergist

General practitioner

Dermatologist

Rheumatologist

Nurse

Physiotherapist

Orthopaedist

Other healthcare professional

I haven't seen any healthcare professionals

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 19: What is the medical specialty of the healthcare professional that you see most often for your … ?

Separate answers for ‘Psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp)’ and ‘Psoriatic arthritis’

Allergist

General practitioner

Dermatologist

Rheumatologist

Nurse

Physiotherapist

Orthopaedist

Other healthcare professional

I Do not have a specific healthcare professional that I see most often

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 20: When did you last see a dermatologist for your psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp)?

In the past week

In the past month

In the past quarter

In the past six months

In the past year

In the past two years

Three years ago or more

I have never seen a dermatologist

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 21: When did you last see a rheumatologist for your psoriatic arthritis?

In the past week

In the past month

In the past quarter

In the past six months

In the past year

In the past two years

Three years ago or more

I have never seen a rheumatologist

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 22: If you think about the last time you were in contact with a physician for your psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp), what…? were the main reasons that you were in contact with the physician? You may choose several options below.

Renewal of a prescription

My symptoms had worsened

General follow‐up

To talk about possible side‐effects from medication

I had side‐effects from a medication

To discuss treatment options

To discuss test results

To take tests (such as a blood test)

To receive light therapy

Psychological reasons (e.g. depression or anxiety)

Other reason, what? – Free text answer

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 23: If you think about the last time you were in contact with a physician for your psoriatic arthritis, what…? were the main reasons that you were in contact with the physician? You may choose several options below.

Renewal of a prescription

My symptoms had worsened

General follow‐up

To talk about possible side‐effects from medication

I had side‐effects from a medication

To discuss treatment options

To discuss test results

To take tests (such as a blood test)

Psychological reasons (e.g. depression or anxiety)

Other reason, what? – Free text answer

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 24: Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the healthcare system and treatment of your … ?

Separate answers for ‘Psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp)’ and ‘Psoriatic arthritis’

Very dissatisfied

Neither dissatisfied nor satisfied

Quite satisfied

Very satisfied

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 25a: Why are you dissatisfied with the healthcare system or treatment of your psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp)?

Free text answer

Question 25b: Why are you satisfied with the healthcare's system or treatment of your psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp)?

Free text answer

Question 26a: Why are you dissatisfied with the healthcare's system or treatment of your psoriatic arthritis?

Free text answer

Question 26b: Why are you satisfied with the heathcare's system or treatment of your psoriatic arthritis?

Free text answer

Question 27: Have you ever changed physician because you were dissatisfied with the management or treatment of your …?

Separate answers for ‘Psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp)’ and ‘Psoriatic arthritis’

Yes, once

Yes, several times

No, I never had the reason to change

No, I never had the option to change

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 28: Have you had a dialogue with your physician about using any of the below treatment options for your psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis?

Treatment options:

-

•

Oral (tablet) or injectable methotrexate

-

•

Oral (tablet) medications (other than methotrexate)

-

•

Injectable or intravenous biologic medication

-

i)

We discussed it but I never used it

-

ii)

We discussed it and I used it/will use it

-

iii)

We never discussed it

-

iv)

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 29: Why did you decide not to use oral (tablet) or injectable methotrexate?

Free text answer

Question 30: Why did you decide not to use an oral (tablet) medication (other than methotrexate)?

Free text answer

Question 31: Why did you decide not to use an injectable or intravenous biologic medication?

Free text answer

Question 32: Are you using any of the following treatments for your psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis?

Treatment options:

Emollients (such as creams or ointments without cortisone)

Topical cortisone treatments (topical steroids)

Alternative treatments (e.g. from health food stores)

Light treatment (e.g. UV treatment)

Oral (tablet) or injectable methotrexate

Oral (tablet) medications (other than methotrexate)

Injectable or intravenous biologic medication

Other treatment

Yes, I'm currently using it

No, I used it but stopped

No, I never used it

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 33: How long did you take the oral (tablet) or injectable methotrexate for before you stopped?

A week or less

Two to three weeks

A month

A quarter (three months)

Half a year

One year

Two years

More than two years

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 34: In general, how satisfied or dissatisfied are/were you with using oral (tablet) or injectable methotrexate?

Very dissatisfied

Quite dissatisfied

Neither dissatisfied nor satisfied

Quite satisfied

Very satisfied

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 35: Why are/were you dissatisfied with oral (tablet) or injectable methotrexate?

I experienced side‐effects, e.g. nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or fever

I currently have/had problems with my liver

I have/had to change my lifestyle too much, e.g. limit the alcohol intake or follow a specific diet

I do not/did not get enough effect

I do not/did not get any effect at all

I'm not/I wasn't able to keep up with my daily activities (e.g. missed work; missed family/personal time)

I am/was concerned about the long‐term safety

It's too difficult to remember to take the medication

Other

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 36: For how long did you take the injectable or intravenous biologic medication before you stopped?

A week or less

Two to three weeks

A month

A quarter (three months)

Half a year

One year

Two years

More than two years

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 37: When you first were prescribed the biologic medication, was it mainly yourself requesting the treatment or was it the doctor's suggestion?

The doctor first suggested that I use the treatment

I was the one who first suggested that I use the treatment

Both the doctor and I suggested that I use the treatment

None of the above

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 38: How satisfied or dissatisfied are/were you with using the biologic medication?

Very dissatisfied

Quite dissatisfied

Neither dissatisfied nor satisfied

Quite satisfied

Very satisfied

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 39: Why are/were you dissatisfied with the biologic medication?

I experienced side‐effects, e.g. nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or fever

I have/had to change my lifestyle too much, e.g. limit the alcohol intake or follow a specific diet

I do not/did not get enough effect

I do not/did not get any effect at all

I'm not/I wasn't able to keep up with my daily activities (e.g. missed work; missed family/personal time)

I do not like to self‐inject

I am/was concerned about the long‐term safety

It's too difficult to remember to take the medication

I get/got injection‐site reactions

Other

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Question 40: How would you evaluate the following treatment types in regards to health risks of long‐term use?

Treatment types

Topical steroids, e.g. cortisone salves or creams

Oral (tablet) or injectable methotrexate

Oral (tablet) medications (other than methotrexate)

Injectable or intravenous biologic medication

No health risks at all

Quite low health risks

Some health risks

Quite large health risks

Very large health risks

Do not know

Question 41: Do you think there is a good or bad range of treatment options available today for your … ?

Separate answers for ‘Psoriasis (on skin, nails or scalp)’ and ‘Psoriatic arthritis’

Very bad range

Quite bad range

Neither good nor bad range

Quite good range

Very good range

Do not know

Question 42: If you think about your psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis as a whole, what is most important to you in terms of support or treatment?

Free text answer

Question 43: Where do you get most of your information about psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis? You may choose a maximum of three options below.

Doctors

Nurses

Other health professionals

Other patients

Family or friends

Patient organisations

Books

Library

Internet – search engines (such as Google)

Internet – specific disease‐related sites

Internet – forums

Internet – other

Television

Radio

Newspapers

Magazines

Other, what? – Free text answer

Do not know

Question 44: Are you a member of any patient organisation for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis?

Sweden

Yes, Psoriasisförbundet

Yes, Reumatikerförbundet

Yes, another organisation

No

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Norway

Yes, Psoriasis‐ og eksemforbundet

Yes, Norsk Revmatikerforbund

Yes, another organisation

No

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Denmark

Yes, Danmarks Psoriasis Forening

Yes, Gigtforeningen

Yes, another organisation

No

Do not know/do not wish to answer

Conflicts of interest

KS Tveit has served as a consultant or lecturer for, or received travel support from AbbVie, Novartis, Almirall, Orion, Janssen, Mundipharma, Pfizer, Serona, Shire, Boehringer Ingelheim and Celgene, outside the submitted work. A Duvetorp has received grants from Philips and AbbVie and personal fees from Celgene and Lilly, outside the submitted work. M Østergaard has received a grant from AbbVie during the conduct of the study, grants, personal fees and non‐financial support from AbbVie, UCB and Merck, grants and personal fees from BMS, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Celgene, Sanofi, Regeneron and Novartis, personal fees and non‐financial support from Janssen and personal fees and non‐financial support from Pfizer and Roche, outside the submitted work. L Skov has received grants from Pfizer, AbbVie, Novartis and Janssen and has served as a consultant and/or paid speaker for and/or participated in clinical trials sponsored by AbbVie, Janssen, Celgene, Novartis, Sanofi, Lilly, Leo Pharma and Almirall, outside the submitted work. K Danielsen has served as a consultant or lecturer for, or received travel support from Galderma, AbbVie, Novartis, Almirall, Meda Pharma and Celgene, outside the submitted work. L Iversen has received grants from AbbVie, Pfizer and Novartis and has served as a consultant and/or paid speaker for and/or participated in clinical trials sponsored by AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Celgene, Centocor, Lilly, Janssen Cilag, Leo Pharma, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB, outside the submitted work. O Seifert has served as a consultant or paid speaker for, or received grants or travel support from AbbVie, Novartis, Pfizer, Almirall and Leo Pharma, outside the submitted work.

Funding source

The NORPAPP was sponsored by Celgene Corporation. The authors received editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript from SuccinctChoice Medical Communications, funded by Celgene Corporation.

References

- 1. Danielsen K, Olsen AO, Wilsgaard T, Furberg AS. Is the prevalence of psoriasis increasing? A 30‐year follow‐up of a population‐based cohort. Br J Dermatol 2013; 168: 1303–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Danielsen K, Duvertorp A, Iversen L et al Prevalence of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and patient perceptions of severity in Sweden, Norway and Denmark: results from the Nordic patient survey of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Acta Derm Venereol 2018. Aug 7. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3017. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Modalsli EH, Snekvik I, Asvold BO, Romundstad PR, Naldi L, Saunes M. Validity of self‐reported psoriasis in a general population: the HUNT study, Norway. J Invest Dermatol 2016; 136: 323–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lindberg M, Isacson D, Bingefors K. Self‐reported skin diseases, quality of life and medication use: a nationwide pharmaco‐epidemiological survey in Sweden. Acta Derm Venereol 2014; 94: 188–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jensen P, Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, Hansen PR, Linneberg A, Skov L. Cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with psoriasis: a cross‐sectional general population study. Int J Dermatol 2013; 52: 681–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, Clegg DO, Nash P. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: ii14–ii17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization . Global report on psoriasis. 2016; 1–3. Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204417 (Last accessed 20 Jan 2018).

- 8. Zachariae H, Zachariae R, Blomqvist K et al Quality of life and prevalence of arthritis reported by 5795 members of the Nordic Psoriasis Associations. Data from the Nordic Quality of Life Study. Acta Derm Venereol 2002; 82: 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kragballe K, Gniadecki R, Mork NJ, Rantanen T, Stahle M. Implementing best practice in psoriasis: a Nordic expert group consensus. Acta Derm Venereol 2014; 94: 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mrowietz U, Steinz K, Gerdes S. Psoriasis: to treat or to manage? Exp Dermatol 2014; 23: 705–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Reich K et al Definition of treatment goals for moderate to severe psoriasis: a European consensus. Arch Dermatol Res 2011; 303: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nast A, Gisondi P, Ormerod AD et al European S3‐guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris ‐ update 2015 ‐ short version ‐ EDF in cooperation with EADV and IPC. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29: 2277–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. NICE . Clinical guideline [CG153] Psoriasis: assessment and management. 2012; Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153 (Last accessed 18 Jan 2018).

- 14. Nast A, Jacobs A, Rosumeck S, Werner RN. Efficacy and safety of systemic long‐term treatments for moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135: 2641–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jabbar‐Lopez ZK, Yiu ZZN, Ward V et al Quantitative evaluation of biologic therapy options for psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: 2644–2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahn CS, Gustafson CJ, Sandoval LF, Davis SA, Feldman SR. Cost effectiveness of biologic therapies for plaque psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2013; 14: 315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cheng J, Feldman SR. The cost of biologics for psoriasis is increasing. Drugs Context 2014; 3: 212266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Armstrong AW, Robertson AD, Wu J, Schupp C, Lebwohl MG. Undertreatment, treatment trends, and treatment dissatisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys, 2003–2011. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149: 1180–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lambert J, Ghislain PD, Lambert J, Cauwe B, Van den Enden M. Treatment patterns in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: results from a Belgian cross‐sectional study (DISCOVER). J Dermatolog Treat 2017; 28: 394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J et al Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population‐based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 70: 871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Poulin Y, Papp KA, Wasel NR et al A Canadian online survey to evaluate awareness and treatment satisfaction in individuals with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Int J Dermatol 2010; 49: 1368–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reich K, Kruger K, Mossner R, Augustin M. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of psoriatic arthritis in Germany: a prospective interdisciplinary epidemiological study of 1511 patients with plaque‐type psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2009; 160: 1040–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van de Kerkhof PC, Reich K, Kavanaugh A et al Physician perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: results from the population‐based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29: 2002–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Augustin M, Eissing L, Langenbruch A et al The German National Program on Psoriasis Health Care 2005–2015: results and experiences. Arch Dermatol Res 2016; 308: 389–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Langenbruch A, Radtke MA, Jacobi A et al Quality of psoriasis care in Germany: results of the national health care study “PsoHealth3”. Arch Dermatol Res 2016; 308: 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kavanaugh A, Helliwell P, Ritchlin CT. Psoriatic arthritis and burden of disease: patient perspectives from the population‐based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) Survey. Rheumatol Ther 2016; 3: 91–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kristiansen IS, Pedersen KM. Health care systems in the Nordic countries ‐ more similarities than differences? Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2000; 120: 2023–2029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Putrik P, Ramiro S, Kvien TK et al Inequities in access to biologic and synthetic DMARDs across 46 European countries. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]