Abstract

Children's friendships are important for well‐being and school adjustment, but few studies have examined multiple indices of friendships together in middle childhood. The current study surveyed 7‐ to 11‐year‐olds (n = 314) about their friendships, best friendships, friendship quality and indices of self‐worth, identification with peers, and identification with school. Peer relationships were positively related to self‐worth, but not identification with peers or school. Best friendship quality moderated the relationship between number of reciprocated friendship nominations and self‐worth. Children with a reciprocated best friend had higher friendship quality and peer identification than others. Where best friendship was reciprocated, the relationship with identification with peers was mediated via positive friendship quality. The results suggest that friendship reciprocity is particularly relevant for children's self‐worth and identification with peers. The findings are discussed in relation to the importance of fostering the development of reciprocated friendships.

Statement of contribution.

What is already known on this subject?

Friendships are related to well‐being, school relations, and how young people feel about their peers at school.

Friendship quality may be important in moderating the relationship between peer relations and adjustment.

What does this study add?

Various aspects of friendships are studied simultaneously with younger children than much previous research.

Reciprocated best friendships were better quality than partial or non‐reciprocated best friendships.

Friendship reciprocity was most relevant for children's self‐worth and peer identification.

Keywords: friendship quality, middle childhood, peer identification, reciprocal friendship, school identification, self‐worth

Background

Children's peer relationships are related to their functioning in multiple ways (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006) and can contribute to their social and emotional development positively and negatively (Hartup, 1996). Children's relationships with their peers are linked to well‐being (Holder & Coleman, 2015), psychological adjustment (Erdley, Nangle, Newman, & Carpenter, 2001), engagement with school (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2007), and broader feelings towards peers (Zimmer‐Gembeck, Waters, & Kindermann, 2010). Although it has been suggested that the different aspects of peer relations, friendships, best friendships, friendship quality and reciprocity, may have different functions, few studies have examined these together. The current study investigates the relationship between different aspects of peer relations and the self‐worth, identification with peers, and identification with school among children during middle childhood (aged 7–11 years).

Peer relations involve relationships within the peer group (such as peer status and peer acceptance) and between dyads (such as reciprocated friendships, relationship quality and other connections like bully–victim relationships) (Gifford‐Smith & Brownell, 2003; Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995). Peer status is both independent from and linked to friendship (Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995), with some children who are generally well‐liked by peers not having friends, and others who are rejected having reciprocated friendships (Vandell & Hembree, 1994).

The functions served by peer status and friendship differ. Peer status and popularity are group‐based and may offer a sense of inclusion and acceptance by others. Friendships tend to be localized to a close dyadic relationship and therefore provide security, intimacy, and trust (Bukowski & Hoza, 1989). According to Bukowski (2001), friendship has four main functions: It provides a sense of self‐value and personal validation; serves a protective function; facilitates learning and development of new skills; and shapes development through shared cultures. Not having a friend in childhood is related to long‐term negative outcomes including increased risk for psychological difficulties and symptoms of depression in adulthood (Bagwell, Newcomb, & Bukowski, 1998; Bagwell, Schmidt, Newcomb, & Bukowski, 2001; Sakyi, Surkan, Fombonne, Chollet, & Melchior, 2015).

Peer relationships are important because people have a profound ‘need to belong’. Forming meaningful bonds with others facilitates a sense of relatedness, connectedness, and belonging (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Peer rejection is related to subsequent poorer self‐esteem (Jiang, Zhang, Ke, Hawk, & Qui, 2015), whereas children with reciprocated friends tend to feel better about themselves, are more sociable, prosocial, happier, and less likely to be bullied (Cheng & Furnham, 2002; Kendrick, Jutengren, & Stattin, 2012; Malcolm, Jensen‐Campbell, Rex‐Lear, & Waldrip, 2006; Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995).

A defining characteristic of friendship is that it is reciprocated (Bagwell & Schmidt, 2011). Friendship is typically assessed via sociometric measures, where children are asked to nominate their best friend, or several friends (Rubin, Bukowski, & Bowker, 2015). If the child (or children) they name also nominates them, a reciprocal friendship is identified. Some children may nominate a child they would ideally like to be friends with, even if this is not reciprocated by the other child (Gifford‐Smith & Brownell, 2003). This unilateral relationship may still be meaningful for the individual. However, there are differences in social interactions and in how conflict is handled and resolved when friendships are not reciprocated (Hartup, 1996; Hartup, Laursen, Stewart, & Eastenson, 1988).

Friendship quality in early adolescence is higher within reciprocated than non‐reciprocated friendships (Linden‐Andersen, Markiewicz, & Doyle, 2009). Berndt (2002) suggested that the benefits associated with friendship vary depending on the quality of the relationship. Friendship quality can buffer against adjustment problems (Bollmer, Milich, Harris, & Maras, 2005; Malcolm et al., 2006; Tu, Erath, & Flanagan, 2012) and positive friendship quality is related to feelings of happiness, life satisfaction, and self‐esteem (Raboteg‐Savic & Sakic, 2014). The quality of friendship could make a difference to how children feel about themselves, their school, and their peers (Gifford‐Smith & Brownell, 2003).

Different aspects of peer relations appear to meet different social needs. Klima and Repetti (2008) found that children without support from close friends did not develop maladjustment symptoms, whereas children with low levels of peer acceptance did. This highlights the importance of studying the different aspects of peer relations and friendships together (Erdley et al., 2001), as they serve different functions and may have unique contributions to children's well‐being and adjustment over time (Bagwell et al., 1998; Bukowski & Hoza, 1989). Some aspects of friendships can cushion the negative effects of other peer relations, with adolescents who were unpopular in the peer group, but who had a good quality friendship, being ‘buffered’ from adjustment problems (Waldrip, Malcolm, and Jensen‐Campbell (2008)). Similarly, Laursen, Bukowski, Aunola, and Nurmi (2007) found that having a friend buffered the negative effects of social isolation by peers. Taken together, this suggests that adjustment and friendship are related, specifically in terms of the quality of the friendship. One can speculate that good quality friendships provide the opportunity to learn and rehearse prosocial skills and healthy empathic behaviours (Bollmer et al., 2005), but it may also be the case that children with poorer psychological functioning may find it more difficult to form these friendships in the first place (Klima & Repetti, 2008).

Peer relations are associated with school adjustment (King, 2015; Ladd, 1990). School adjustment is important as it is linked to future academic success and a decreased likelihood of dropping‐out (Ladd, 1990; Li, Lerner, & Lerner, 2010; Slaten, Ferguson, Allen, Brodrick, & Waters, 2016). Literature on school adjustment has examined various factors including school engagement, liking, and academic performance. Peer acceptance predicts school liking and engagement (Betts, Rotenberg, Trueman, & Stiller, 2012; Boulton, Don, & Boulton, 2011), whereas peer rejection is related to disengagement with school (Furrer & Skinner, 2003), lower school performance, aspiration, and social participation (Bagwell et al., 1998). Children with more reciprocated friends showed higher school liking and academic competence (Erath, Flanagan, & Bierman, 2008). However, Erath et al. (2008) noted that the positive correlates of friendships were only evident if the friendship had positive features – suggesting that positive friendship quality may be important in moderating the link between friendship and feelings towards school. Conflict within friendships is associated with self‐reported school stress during middle childhood (Wang & Fletcher, 2017), whereas adolescents who have best friendships with positive characteristics report more involvement in school activities (Berndt & Keefe, 1995), more positive attitudes towards school (Schwartz, Gorman, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2008), and higher school liking and academic competence (Erath et al., 2008). Friendships can ‘make school comfortable’ (p. 69), with adolescents who do not feel accepted by the wider peer group reporting that having a supportive friend alleviated feelings of isolation (Hamm & Faircloth, 2005).

Peer relations also relate to how children feel towards the wider peer group. Zimmer‐Gembeck et al. (2010) found that 10‐ to 13‐year‐olds who perceived their peers negatively were less liked by their peers and liked their peers less. Rudolph, Hammen, and Burge (1995) reported that children aged 7–12 years who held negative representations of peers were more likely to be rejected by the peer group.

Few studies have examined the relationship between the different peer relation variables and identification with the peer group, school identification, and feelings of general self‐worth during middle childhood. Middle childhood is a particularly important developmental period for peer relations. Social time spent with peers increases, tightly knit cliques develop, group identity and acceptance become more central, and some aspects of peer relations become more stable (Camodeca, Meerum, & Schengel, 2002; Gifford‐Smith & Brownell, 2003). Additionally, in the United Kingdom, children of this age are typically in a constant class group, often with the same class of children for many years, meaning that peer relations may be particularly relevant to their feelings about themselves, and school. Middle childhood is a sensitive time for social and emotional development, with peer problems such as peer rejection, victimization, and friendlessness being associated with later psychological adjustment (Pederson, Vitaro, Barker, & Borge, 2007; Schwartz, Lansford, Dodge, Petit, & Bates, 2015).

The current research examined the relationship between 7‐ and 11‐year‐old children's peer relations and the relationship with self‐worth and peer and school identification. It was predicted that being identified as a friend by peers would be related to positive feelings of peer and school identification and self‐worth (Betts et al., 2012; Waldrip et al., 2008; Zimmer‐Gembeck et al., 2010). It was hypothesized that best friendship quality would moderate the relationship between being liked by peers and peer and school identification and self‐worth (Hamm & Faircloth, 2005). It was also predicted that children with reciprocated best friendship nominations would report higher friendship quality (Linden‐Andersen, Markiewicz, & Doyle, 2009), more identification with peers and school and higher self‐worth than children with unreciprocated best friendships (Erath et al., 2008). It was hypothesized that best friendship quality would mediate the relationship between best friendship reciprocity and peer and school identification and self‐worth.

Method

Participants

Children from 13 classes in five primary schools in England participated in the research (N = 314,1 52.5% female). Participants were aged between 7 and 11 years (M = 10.01, SD = 0.94), in Years 3–6 (Year 3 n = 26, Year 4 n = 28, Year 5 n = 135, Year 6 n = 126). The schools were selected via opportunity sampling through personal contacts of the researchers. All schools were mainstream state funded primary schools, based in low to middle socioeconomic areas. Based on an average class size of 30 pupils, the response rate ranged from 50 to 100% (M = 80.2%). Although participation rates can affect the reliability and validity of peer nomination data (Bukowski, Cillessen, & Velasquez, 2012), participation above 60% can produce reliable sociometric nomination data (Cillessen & Marks, 2011; Crick & Ladd, 1989), and nominations for overt aggression and prosocial behaviour are reliable at participation rates as low as 40% (Marks, Babcock, Cillessen, & Crick, 2013).

Measures

‘About Me’

The ‘About Me’ questionnaire measures self‐worth, self‐concept, and social identity, and in its full form has 29 items across seven sub‐scales (Maras, 2002). It has adequate internal reliability (overall α = .88; specific sub‐scale alphas ranging from .64 to .76, Maras, Moon, & Zhu, 2012) and has been used in several other studies (e.g., Knowles & Parsons, 2009; Maras, Brosnan, Faulkner, Montgomery, & Vital, 2006). For each question, children rate the extent to which they agree or disagree by choosing an appropriate face on a scale from very sad (1) (equating to strongly disagree or strong ‘no’), to very happy (5) (equating to strongly agree or strong ‘yes’). Three sub‐scales from the primary version were used for this study: Identification with Peers (four items, α = .57), which examines children's connection to their peers (e.g., ‘how much you like playing with your friends’; ‘how much your friends are like you’); Identification with School (four items, α = .42), which assesses children's connection to school (e.g., ‘how much you like being at school’; ‘how much you like doing the same things as other children at school’); and Self‐Worth (five items, α = .71) which measures children's feelings about themselves (e.g., ‘what you think about being you’; ‘what you think about the way you look’).2

Friendship nomination

As is common practice in peer nomination, children were asked to nominate up to three of their classmates who were their friends (Bagwell & Schmidt, 2011). They were also asked to identify their best friend. We did not provide a definition of friendship or restrict who children could nominate – providing it was someone in their class.

Friendship qualities scale

The FQS consists of 23 statements describing the child's relationship with their best friend and has been widely used (Bagwell & Schmidt, 2011; Bukowski, Hoza, & Boivin, 1994), with favourable validity and internal reliability (Bukowski et al., 1994). The FQS measures five dimensions of friendship quality: Companionship (four items, α = .59), for example ‘My friend and I spend all our free time together’; Conflict (four items, α = .78), for example ‘My friend and I can argue a lot’; Help (five items, α = .77), for example ‘My friend helps me when I am having trouble with something’; Security (five items, α = .71), for example ‘If my friend or I do something that bothers the other one of us, we can make up easily’; and Closeness (five items, α = .80), for example ‘Sometimes my friend does things for me or makes me feel special’. For each statement, they were asked to indicate on a 5‐point scale from ‘not at all true’ (1) to ‘really true’ (5).

Procedure

The study was approved by both University Research Ethics Committees. Consent was obtained from the head teacher, ‘opt out’ consent from parents/carers of children, and assent from children. The study was conducted during class time. Each question was read out to the class by a researcher and the children wrote their answers individually without discussing them with others. Children were told that did not have to answer any questions they did not wish to. The importance of keeping their answers and friendship nominations private was emphasized. It took approximately 20 min to complete the questionnaire.

Results

Descriptives

Scores on individual items were totalled for each sub‐scale on the About Me and FQS. Means and standard deviations (Table 1) show that children reported high levels of Identification with Peers and School, high Self‐Worth, and good quality relationships with their best friends. Some of the data violated parametric assumptions, so bootstrapping was employed in subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Pearson correlations, means and standard deviations for About Me measure, and sub‐scales on the Friendship Qualities Scale (FQS)1

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | n | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. About me: Peers | – | 304 | 16.11 | 2.56 | |||||||

| 2. About me : School | .37*** | – | 305 | 12.19 | 2.60 | ||||||

| 3. About me: General self‐worth | .41*** | .31** | – | 302 | 21.27 | 3.24 | |||||

| 4. FQS Companionship | .39*** | .17** | .26*** | – | 310 | 13.94 | 3.13 | ||||

| 5. FQS Conflict | −.24*** | −.18** | −.18** | −.07 | – | 299 | 8.06 | 3.58 | |||

| 6. FQS Help | .41*** | .20** | .34*** | .54*** | −.20** | – | 299 | 20.60 | 3.85 | ||

| 7. FQS Security | .34*** | .27*** | .26*** | .44*** | −.29*** | .66*** | – | 305 | 20.23 | 4.03 | |

| 8. FQS Closeness | .47*** | .25*** | .35*** | .43*** | −.24*** | .60*** | .61*** | – | 307 | 21.57 | 3.47 |

Analyses were run with 1,000 bootstraps.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05; n = 236.

1 Due to some incomplete questionnaires or missing question responses, final ns for analysis ranged from 256 to 310.

Significant positive correlations were found between the About Me and the FQS sub‐scales of Companionship, Help, Security and Closeness. Scores on Conflict were negatively correlated with Help, Security, and Closeness. Identification with School, Identification with Peers, and Self‐Worth were related to higher quality friendships and lower Conflict (Table 1).

Friendship, the About Me, and FQS

The friendship and best friendship nominations were compared within each class to identify mutual friendships. Relationships between peer relations and the About Me and FQS dimensions were examined at three levels: (1) the number of friend nominations received, (2) the number of best friend nominations received, and (3) the number of reciprocated nominations received. Where these reports could be affected by differing class sizes, they were standardized to z scores. Friend nominations correlated significantly with best friend nominations (r = .75, p < .001) and reciprocated nominations (r = .60, p < .001); best friend nominations correlated significantly with reciprocated nominations (r = .49, p < .001).

The three measures of peer relations demonstrated similar patterns of correlations with the About Me and FQS. Overall friendship nominations were significantly and positively correlated with Self‐Worth and positive aspects of friendship quality (Companionship, Security, and Help). Best friendship nominations were positively correlated with Self‐Worth and Companionship, Security and Help, and negatively with Conflict. Reciprocated friendship nominations were significantly and positively related to Self‐worth, Help, and Companionship and negatively to Conflict (Table 2).3

Table 2.

Relationship between number of friendship nominations and scores on ‘About Me’ and FQS measures

| Measure | Number of friendship nominations | Number of best friend nominations | Number of reciprocal nominations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. About me: Peers | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| 2. About me: School | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.04 |

| 3. About me: General self‐worth | 0.17* | 0.15* | 0.13* |

| 4. FQS Companionship | 0.15* | 0.18** | 0.14* |

| 5. FQS Conflict | −0.11 | −0.14* | −0.16* |

| 6. FQS Help | 0.21** | 0.17** | 0.21** |

| 7. FQS Security | 0.17** | 0.17** | 0.10 |

| 8. FQS Closeness | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

Analyses were run with 1,000 bootstraps.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05; n = 260.

To investigate whether the relationship between these broad peer relations and Self‐Worth was moderated by the quality of a child's relationship with their best friend, a total score for positive friendship quality was calculated by summing Companionship, Help, Security, and Closeness (α = .84). Moderation analyses using bootstrapping with bias corrected confidence estimates were conducted using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013). Variables were centred round the mean. Bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was used (Hayes, 2013) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Moderation of the relationship between friendship measures and self‐worth by friendship quality

| Model 1. Total number of friendship nominations (n = 284) | Model 2. Total number of best friend nominations (n = 283) | Model 3. Total number of reciprocated nominations (n = 284) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | b | t | |

| Constant | 21.39 | 119.71*** | 21.38 | 118.37*** | 21.41 | 120.92*** |

| Friendship Quality (moderator) | 0.08 | 5.10*** | 0.08 | 5.30*** | 0.08 | 5.40*** |

| Total friend nominations (independent Model 1) | 0.38 | 2.13* | ||||

| Friendship quality × total friend nominations (moderation Model 1) | −0.02 | −1.19 | ||||

| Best friend nominations (independent Model 2) | 0.32 | 1.68 | ||||

| Friendship quality × best friend nominations (moderation Model 2) | −0.02 | −1.08 | ||||

| Reciprocated nominations (independent Model 3) | 0.16 | 1.14 | ||||

| Friendship quality × reciprocated nominations (moderation Model 3) | −0.03 | −2.21* | ||||

b = unstandardized coefficient.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

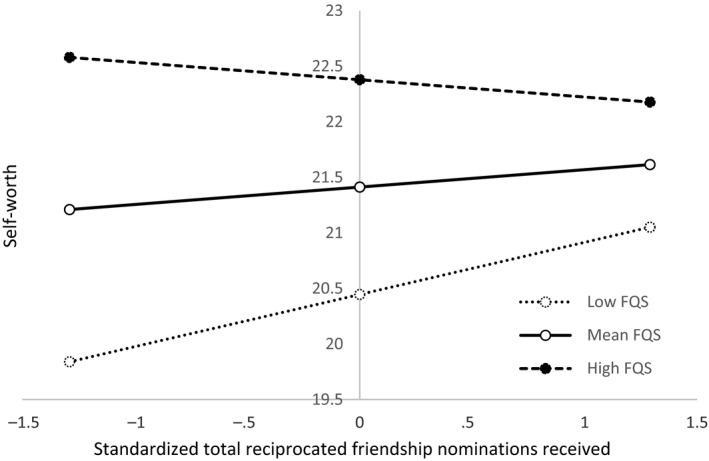

Positive friendship quality did not significantly moderate the relationship between the total number of friend nominations received and Self‐Worth (Model 1 in Table 3) or the relationship between total number of best friend nominations and Self‐Worth (Model 2 in Table 3). Friendship quality significantly moderated the relation between total number of reciprocated friendship nominations received and Self‐Worth (Model 3 in Table 3). The model was significant, R 2 = .13, F(3, 280) = 14.26, p < .001. Friendship quality significantly predicted Self‐Worth. Number of reciprocated nominations received did not significantly predict Self‐Worth when friendship quality was in the model. There was a significant moderating effect of friendship quality, and inclusion of the interaction term significantly increased the variance explained by the model, R 2 Δ = .015, F(1, 280) = 4.89, p < .05. The number of reciprocated friendship nominations received was only significantly and positively related to Self‐Worth at low levels of friendship quality (p < .05). There was no significant relationship between the number of reciprocated friendship nominations received and Self‐Worth at moderate or high levels of friendship quality (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

- Note: Low FQS = friendship quality 1 SD below the mean, High FQS = friendship quality 1 SD above the mean.

Best friendships and friendship quality

Three best friendship groups were identified: (1) reciprocated (both children identified each other as best friend), (2) partially reciprocated (best friend did not identify them as ‘best friend’ but identified them as a ‘friend’), and (3) not reciprocated (best friend did not identify them as ‘best friend’ or ‘friend’).

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to examine differences in the best friendship types on the FQS. There was a significant main effect of best friendship type (Wilks’ λ = .88, F(10, 504) = 3.37, p < .001, = .06). Univariate analyses showed significant effects for Companionship, F(2, 256) = 11.94, p < .001, = .09, Help, F(2, 256) = 8.16, p < .001, = .06, Security, F(2, 256) = 6.87, p = .001, = .05, and Closeness, F(2, 256) = 7.63, p = .001, = .06, but not for Conflict, F(2, 256) = 0.35, p = .71. Post hoc analysis using Bonferroni's correction showed that children who had a reciprocated best friend scored higher than those whose best friendship was partially reciprocated for Companionship (p = .002), Help (p = .008), Security (p = .003), and Closeness (p = .001). Children with a reciprocated best friend also scored higher than those whose best friendship was not reciprocated for Companionship (p < .001), Help (p = .001) and Security (p = .025), but not for Closeness. No other differences reached significance (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean scores on About Me and FQS measures by reciprocal best friendship nomination status (standard deviations in parentheses)

| Measure | Best friendship reciprocated (n = 141) | Best friendship partially reciprocated (n = 69) | Best friendship not reciprocated (n = 75) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. About Me: Peers | 16.70 (2.50) | 15.43 (2.41) | 15.86 (2.72) |

| 2. About Me : School | 12.25 (2.64) | 12.48 (2.54) | 11.87 (2.68) |

| 3. About Me: General self‐worth | 21.74 (3.32) | 20.69 (2.91) | 21.01 (3.23) |

| 4. FQS Companionship | 14.74 (2.89) | 13.20 (2.91) | 13.15 (3.59) |

| 5. FQS Conflict | 7.70 (3.12) | 8.09 (3.48) | 8.16 (4.14) |

| 6. FQS Help | 21.65 (3.12) | 19.51 (4.18) | 19.66 (4.46) |

| 7. FQS Security | 21.15 (3.48) | 18.97 (4.64) | 19.79 (4.32) |

| 8. FQS Closeness | 22.30 (3.19) | 20.19 (3.81) | 21.46 (3.45) |

Best friendships and About Me

A second MANOVA examined differences in best friendship type on the three About Me sub‐scales. There was a significant effect of best friendship type, Wilks’ λ = .94, F(6, 518) = 2.59, p = .018, = .03. Univariate analyses showed that the only significant effect was for Identification with Peers, F(2, 260) = 5.69, p = .004, = .04. Post hoc analysis using Bonferroni's correction indicated that children who had a reciprocated best friend scored significantly higher on Identification with Peers than those whose best friendship was partially reciprocated (p = .006). No other differences reached significance (see Table 4).

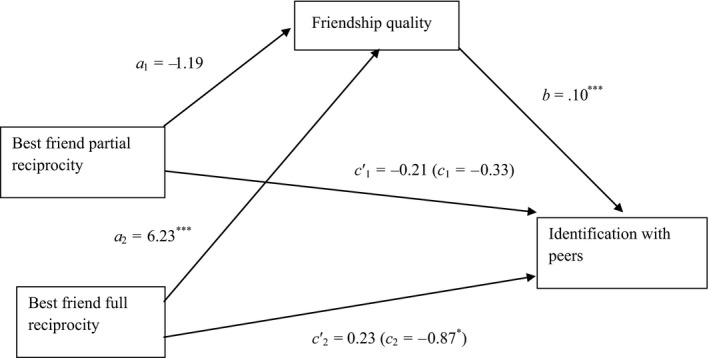

Mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) to examine whether the positive relationship between reciprocity in best friendship and Identification with Peers may be via the higher quality of reciprocated best friendships. Mediation analysis with a multicategorical IV using bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples (described in Hayes & Preacher, 2014) was used. Best friend status was dummy coded: 1 = nomination not reciprocated; 2 = partially reciprocated; and 3 = reciprocated best friend.4 Unreciprocated friendship was used as the reference. Mediation analysis (See Figure 2 and Table 5) indicated that children whose friendship was fully reciprocated reported significantly higher friendship quality than those whose friendship was not reciprocated. Independent of best friend status, friendship quality significantly and positively predicted Identification with Peers. For children whose friendship was reciprocated, relative to those who did not have a reciprocated friendship, there was significant indirect effect of best friendship status on Identification with Peers via friendship quality. When friendship quality was included in the model, the direct effect of having a reciprocated best friendship on Identification with Peers was no longer significant suggesting full mediation.

Figure 2.

- Note: Best friendship not reciprocated used as reference. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 5.

Mediation of the relationship between best friend status and identification with peers by friendship quality

| Outcome | M (friendship quality) | Y (peer identification) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) | Coefficient (SE) | Coefficient (SE) | ||||

| Constant | i 1 | 73.70 (1.41)*** | i 3 | 15.87 (0.31)*** | i 2 | 8.40 (0.95)*** |

| Best Friend Partially Reciprocated | a 1 | −1.19 (2.02) | c 1 | −0.33 (0.45) | c′ 1 | −0.21 (0.40) |

| Best Friend Reciprocated | a 2 | 6.23 (1.74)*** | c 2 | 0.87 (0.38)* | c′ 2 | 0.23 (0.35) |

| Friendship Quality (M) | b | 0.10 (0.01)*** | ||||

Best friendship not reciprocated used as reference.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Discussion

The findings confirm the benefit of looking at different aspects of children's peer relations such as nominations for friendship, best friendships, reciprocity of friendships, and friendship quality as well as the interactions between these variables for furthering our understanding of children's peer relations and adjustment (e.g., Erath et al., 2008; Hoza, Bukowski, & Beery, 2000). The current study focussed on peer relations during middle childhood and builds on existing literature highlighting the establishment of tightly knit reciprocal friendships during this period and their importance for children's feelings about themselves, school, and their peer group more generally (Boulton et al., 2011; Gifford‐Smith & Brownell, 2003; Hamm & Faircloth, 2005; Pederson et al., 2007).

Self‐worth, friendship, and best friendship

As predicted, the broader peer relation variables were all positively correlated with self‐worth (Erdley et al., 2001). Children who received higher numbers of friend, best friend, and reciprocated nominations reported higher levels of self‐worth. It is possible that children with higher self‐worth are more attractive playmates and thus receive more positive nominations from peers. It is also likely that children who have good relations with their peers develop their feelings of self‐worth in part from these positive relationships.

It was predicted that the quality of a child's best friendship may moderate the relationship between self‐worth and levels of friendship nominations received (Hamm & Faircloth, 2005; Waldrip et al., 2008). Although there was no significant effect of the level of reciprocity of best friendship (fully, partially, or not reciprocated) on feelings of self‐worth, it was found that, for children who reported lower levels of friendship quality with their best friend, there was a significant positive relationship between the number of reciprocated friendships they received and their feelings of self‐worth. Children with poorer quality best friendships tended to score lower on self‐worth if they had fewer reciprocated friendships than when they had more reciprocated friends. It is possible that children whose best friendship is of a poorer quality may gain or maintain feelings of self‐worth from their other reciprocated friendships. These relationships could provide the support and closeness which may be lacking from their best friendship and may benefit feelings of self‐worth. Furthermore, children with poorer self‐worth may be those with poorer quality best friendships and fewer reciprocated friends; children with poorer self‐worth may be more likely to expect poorer treatment from others such as victimization (Egan & Perry, 1998) and may thus be more at risk of poorer peer relations.

Identification with peers, friendship, and best friendship

Although the broader peer relations measures obtained in the current study were not associated with peer identification, children with reciprocated best friendships reported higher levels of peer identification than those whose best friendships were partially or not reciprocated. The quality of the best friendship appeared key, with positive friendship quality fully mediating the relation between reciprocity of best friendship and identification with peers. Based on previous research showing an association between negative feelings about the peer group and lower peer acceptance (e.g., Rudolph et al., 1995; Zimmer‐Gembeck et al., 2010), it was expected that poorer peer relations would be related to lower identification with peers. The current study supports and extends this finding by indicating that this may be related to the quality rather than quantity of friendships. Having a high quality relationship with a friend may facilitate interactions with the wider peer group by providing a supportive ally on whom to rely, thus encouraging a more favourable view of the peer group as a whole. It is also possible that having a high quality friendship may positively shape the individual's perceptions of other peers. Furthermore, having a good quality friendship may be an indicator of broader social skills (Fink, Begeer, Peterson, Slaughter, & de Rosnay, 2015) which may facilitate peer interactions and promote a more positive view of the wider peer group.

It is important to note the different concepts of peer perceptions examined in research. In the current study, identification with peers was examined by asking children to rate the degree to which they liked doing things with peers, and how similar they felt their peers were to them. In contrast, Zimmer‐Gembeck et al. (2010) and Rudolph et al. (1995) asked about children's perceptions of negative aspects of peer relations and may tap into less positive perceptions of peer relations than the About Me (Maras, 2002). Furthermore, the current study assessed peer acceptance rather than peer rejection. Research has found that peer liking and peer rejection are not opposites and that some children are highly liked and disliked (Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982). Therefore, these indices of peer relations may differ in their relation to other variables.

Identification with school, friendship, and best friendship

There was no significant relationship between the broader peer relations measures and identification with school. Similarly, reciprocity within best friendships was not significantly associated with identification with school. This contrasted with research reporting links between peer relations and school engagement (Betts et al., 2012) and school liking (Boulton et al., 2011). The different methodologies employed and the different conceptualizations of school identification, engagement or liking between studies may explain this. Betts et al. (2012) looked at teacher reports of child engagement in school and child self‐reports of school liking. Boulton et al. (2011) asked children about how much they liked being at school and how much they preferred not to be at school. In contrast, the current study examined school identification, which may assess different aspects of a child's relationship with school such as liking being at school and how much the child feels that others at school are similar to them (Maras, 2002). This second aspect is different to school liking and school engagement (focussing on on‐task behaviour, orientation, and maturity) examined in previous studies (Betts et al., 2012; Boulton et al., 2011) which may account for the differing findings. Although children may feel connected to their friends and like school, they may feel different from the majority of children at school.

Future studies should explore the various dimensions of school identification, liking, and engagement as different aspects may be differentially related to peer relations. In addition, other peer relations may be relevant to identification with school, such as teacher–child relations, parental attitudes to school, and other individual level factors which may mean that children feel that they differ from others at school.

Friendship quality

Reciprocity was important within best friendships. The findings highlighted the significance of a child's best friend identifying them as their best friend, rather than as one of their friends. Children with reciprocated best friendships had better quality friendships than those whose best friendship was partially reciprocated or whose best friendship was not reciprocated, which supports previous findings in early adolescence and extends them to a younger age group (Linden‐Andersen et al., 2009). Reciprocated friendships were higher on companionship, security, help, and closeness, supporting previous findings suggesting that ‘reciprocity defines a stronger affective tie between children than does the unilateral expression of friendship’ (Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995, p. 340). There were no differences between the groups in levels of conflict reported in their best friendships which also reflects previous research (Hartup et al., 1988). This reciprocity indicates a bidirectional affectional link between two individuals, whereas an individual who indicates that someone is their friend, but this is not mutually felt, may be reporting a desired rather than actual friendship. Research on reciprocity in friendships has indicated a greater level of mutual understanding in reciprocal rather than unilateral friendships (Ladd & Emerson, 1984).

Limitations and future directions

There are several limitations to this study. The cross‐sectional nature meant that hypotheses regarding directionality were driven by previous research. Although mediation analysis is frequently used with cross‐sectional data (e.g., Bøe et al., 2014; Talmon & Ginzburg, 2017), there has been debate regarding its appropriateness with cross‐sectional data (e.g., Cole & Maxwell, 2003). However, more recent work argues that cross‐sectional data can provide useful insights when research is based on prior theory and research (Shrout, 2011). Future studies should aim to examine the developing nature of children's peer relationships and their adjustment over time (Bowker et al., 2010). It would also be interesting to interrogate the friendship patterns and characteristics within middle childhood. Similar to other research (e.g., Parker & Asher, 1993), age trends within our sample were not evident so analyses were combined across year groups. A larger sample within each year group would enable age trends to be analysed in more detail. There may be subtle changes in the composition of friendships during this developmental phase that could be explored using different methods. For example, stability in a best friendship dyad (same child or different child friendship) may have differential outcomes than fluid friendships (Bowker, Rubin, Burgess, Booth‐LaForce, & Rose‐Krasnor, 2006).

The outcome measures were all derived from self‐reports (although the relationship measures were a combination of peer and self‐reports). Future studies should also aim to employ reports from other informants (such as parents/carers and teachers) to examine child self‐worth and school and peer identification. Previous research has occasionally employed teacher or parent reports of children's friendships. However, there is only moderate agreement between teacher and child reports of friendships in elementary school, and child reports are still the ‘gold standard’ (Gest, 2006).

The sub‐scales from the About Me questionnaire (especially Identification with School and Peers) were found to have lower reliability coefficients than those reported in other studies with older children (e.g., Maras et al., 2012) which may question the internal consistency of the scale with a younger sample. Further assessment of the measure – published since this study was conducted – with children aged 6–18 years reports adequate psychometric properties, but the version tested had slightly modified wording, and its validity with other existing measures has yet to be examined (Maras, Thompson, Gridley, & Moon, 2016). Although Maras et al. (2016) report evidence of reasonably sound factorial structure, they note that there may be different interpretations of questions by age, and potential impact of similarly worded items. Therefore, the measure may need further development and testing to ensure it is sufficiently robust. It is possible that the minor wording differences between versions of the measure may have influenced children's responses, and further age comparison analysis may be needed.

A further limitation was that children were asked to report on their friends within their class. It is possible that children may have a best friend in another class or outside of school, which may have limited potential nominations for some children and affected responses. It would be of interest to examine this by enabling children to identify whether their best friend is outside of their class. In addition, in their meta‐analysis, Meter and Card (2016) noted that around half of all friendships during childhood and adolescence were unstable. It would be interesting to examine the impact of these changes in friendships along with the reasons for the dissolution of the friendship.

The findings of the current study confirm and extend previous research showing that friendships, and in particular reciprocated friendships, are important for children's self‐worth and peer identification in middle childhood. Having reciprocated friendships can buffer against a poor quality best friendship in relation to a child's feelings of self‐worth, and friendship quality mediates the relationship between having a reciprocated best friend and identification with peers. Intervention research has shown that taking a dyadic approach to peer relations and encouraging friendship formation, rather than attempting to tackle overall peer group status, can be more effective. For example, Gardner and Gerdes (2015) found that children with ADHD in a social skills training programme showed greater improvements when paired with a ‘buddy’ who was assigned based on children's pre‐existing friendships. The current study appears to support this approach in finding that reciprocated friendships appear to be particularly important for children's adjustment. Future research should consider the varied aspects of peer relations and the different facets of school engagement or identification as well as peer‐related cognitions. In addition, longitudinal research tracking the relationships between these variables would provide more information regarding the relationships over time and across developmental periods.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the children and schools for their participation. Also, thanks to Suzanne Bartholomew and James Crosby for research assistance. Claire Monks would also like to acknowledge funding support from the University of Greenwich.

Footnotes

Due to some incomplete questionnaires or missing question responses, final ns for analysis ranged from 256 to 310.

It should be noted that these alphas are lower than those reported elsewhere, and we address this further in the Discussion.

Correlations were additionally performed to examine the relations between the different measures of peer relations and the About Me and FQS separately by age group (younger; 7–9 years and older; 10–11 years) and by gender. After controlling for multiple analyses using Bonferroni's correction, none of the subsequent analyses reached significance.

Mediation analyses were not performed with Identification with School or Self‐Worth as neither of these were significant in the earlier MANOVA between best friend groups.

References

- Bagwell, C. L. , Newcomb, A. F. , & Bukowski, W. M. (1998). Preadolescent friendship and peer rejection and predictors of adult adjustment. Child Development, 69, 140–153. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell, C. L. , & Schmidt, M. E. (2011). Friendships in childhood & adolescence. London, UK: Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell, C. L. , Schmidt, M. E. , Newcomb, A. F. , & Bukowski, W. M. (2001). Friendship and peer rejection as predictors of adult adjustment. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 91, 25–50. 10.1002/cd.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R. F. , & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, T. J. (2002). Friendship quality and social development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11, 7–10. 10.1111/1467-8721.00157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, T. J. , & Keefe, K. (1995). Friends’ influence on adolescents’ adjustment to school. Child Development, 66, 1312–1329. 10.2307/1131649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts, L. R. , Rotenberg, K. J. , Trueman, M. , & Stiller, J. (2012). Examining the components of children's peer liking as antecedents of school adjustment. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 30, 303–325. 10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bøe, T. , Sivertsen, B. , Heiervang, E. , Goodman, R. , Lundervold, A. J. , & Hysing, M. (2014). Socioeconomic status and child mental health: The role of parental emotional well‐being and parenting practices. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 705–715. 10.1007/s10802-013-9818-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollmer, J. , Milich, R. , Harris, M. , & Maras, M. (2005). A friend in need: The role of friendship quality as a protective factor in peer victimization and bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 701–712. 10.1177/0886260504272897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, M. J. , Don, J. , & Boulton, L. (2011). Predicting children's liking of school from their peer relationships. Social Psychology of Education, 14, 489–501. 10.1007/s11218-011-9156-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowker, J. C. , Fredstrom, B. K. , Rubin, K. H. , Rose‐Krasnor, L. , Booth‐LaForce, C. , & Laursen, B. (2010). Distinguishing children who form new best‐friendships from those who do not. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 707–725. 10.1177/0265407510373259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowker, J. C. , Rubin, K. H. , Burgess, K. B. , Booth‐LaForce, C. , & Rose‐Krasnor, L. (2006). Behavioral characteristics associated with stable and fluid best friendship patterns in middle childhood. Merrill‐Palmer Quarterly, 52, 671–693. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski, W. M. (2001). Friendship and the worlds of childhood. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 91, 93–105. 10.1002/cd.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski, W. M. , Cillessen, A. H. N. , & Velasquez, A. M. (2012). Peer ratings In Laursen B., Little T. D. & Card N. A. (Eds.), Handbook of developmental research methods (pp. 211–231). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski, W. M. , & Hoza, B. (1989). Popularity and friendship: Issues in theory, measurement, and outcome In Berndt T. & Ladd G. (Eds.), Peer relationships in child development (pp. 15–45). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski, W. M. , Hoza, B. , & Boivin, M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre‐ and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the friendship qualities scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 471–484. 10.1177/0265407594113011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camodeca, M. , Meerum, M. , & Schengel, C. (2002). Bullying and victimization among school‐age children: Stability and links to proactive and reactive aggression. Social Development, 11, 332–345. 10.1111/1467-9507.00203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H. , & Furnham, A. (2002). Personality, peer relations, and self‐confidence as predictors of happiness and loneliness. Journal of Adolescence, 25, 327–339. 10.1006/jado.2002.0475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen, A. H. N. , & Marks, P. E. L. (2011). Conceptualizing and measuring popularity In Cillessen A. H. N., Schwartz D. & Mayeux L. (Eds.), Popularity in the peer system (pp. 25–56). New York, NY: Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen, A. H. N. , & Mayeux, L. (2007). Expectations and perceptions at school transitions: The role of peer status and aggression. Journal of School Psychology, 45, 567–586. 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coie, J. D. , Dodge, K. A. , & Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A cross‐age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557–570. 10.1037/0012-1649.18.4.557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D. A. , & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 558–577. 10.1037/0021-843x.112.4.558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick, N. R. , & Ladd, G. W. (1989). Nominator attrition: Does it affect the accuracy of children's sociometric classifications? Merrill‐Palmer Quarterly, 35, 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, S. K. , & Perry, D. G. (1998). Does low self‐regard invite victimization? Developmental Psychology, 34, 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erath, S. A. , Flanagan, K. S. , & Bierman, K. L. (2008). Early adolescent school adjustment: Associations with friendship and peer victimization. Social Development, 17, 853–870. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00458.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erdley, C. A. , Nangle, D. W. , Newman, J. E. , & Carpenter, E. M. (2001). Children's friendship experiences and psychological adjustment: Theory and research. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 91, 5–24. 10.1002/cd.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink, E. , Begeer, S. , Peterson, C. C. , Slaughter, V. , & de Rosnay, M. (2015). Friendlessness and theory of mind: A prospective longitudinal study. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 33, 1–17. 10.1111/bjdp.12060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furrer, C. , & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children's academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 148–162. 10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, D. M. , & Gerdes, A. C. (2015). A review of peer relationships and friendships in youth with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19, 844–855. 10.1177/1087054713501552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gest, S. D. (2006). Teacher reports of children's friendships and social groups: Agreement with peer reports and implications for studying peer similarity. Social Development, 15, 248–259. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2006.00339.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford‐Smith, M. E. , & Brownell, C. A. (2003). Childhood peer relationships: Social acceptance, friendships and peer networks. Journal of School Psychology, 41, 235–284. 10.1016/S0022-4405(03)00048-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm, J. V. , & Faircloth, B. S. (2005). The role of friendship in adolescents’ sense of school belonging. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 107, 61–78. 10.1177/0272431693013001002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup, W. W. (1996). The company they keep: Friendships and their developmental significance. Child Development, 67, 1–13. 10.2307/1131681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup, W. W. , Laursen, B. , Stewart, M. I. , & Eastenson, A. (1988). Conflict and the friendship relations of young children. Child Development, 59, 1590–1600. 10.2307/1130673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis: A regression based approach. New York, NY: The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. , & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67, 451–470. 10.1111/bmsp.12028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder, M. D. , & Coleman, B. (2015). Children's friendships and positive well‐being In Demir M. (Ed.), Friendship and happiness: Across the lifespan and cultures (pp. 81–97). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hoza, B. , Bukowski, W. M. , & Beery, S. (2000). Assessing peer network and dyadic loneliness. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 119–128. 10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J. , Zhang, Y. , Ke, Y. , Hawk, S. , & Qui, H. (2015). Can't buy me friendship? Peer rejection and adolescent materialism: Implicit self‐esteem as a mediator. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 58, 48–55. 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick, K. , Jutengren, G. , & Stattin, H. (2012). The protective role of supportive friends against bullying perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1069–1080. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, R. B. (2015). Sense of relatedness boosts engagement, achievement, and well‐being: A latent growth model study. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 42, 26–38. 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klima, T. , & Repetti, R. L. (2008). Children's peer relations and their psychological adjustment: Differences between close friendships and the larger peer group. Merrill‐Palmer Quarterly, 54, 151–178. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, C. , & Parsons, C. (2009). Evaluating a formalised peer mentoring programme: Student voice and impact audit. Pastoral Care in Education: An International Journal of Personal, Social and Emotional Development, 27, 205–218. 10.1080/02643940903133888 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, G. (1990). Having friends, keeping friends, making friends, and being liked by peers in the classroom: Predictors of children's early school adjustment? Child Development, 61, 1081–1100. 10.2307/1130877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, G. W. , & Emerson, E. S. (1984). Shared knowledge in children's friendships. Developmental Psychology, 20, 932–940. https://doi.org/10.1037%2F0012-1649.20.5.932 [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, B. , Bukowski, W. M. , Aunola, K. , & Nurmi, J. E. (2007). Friendship moderates prospective associations between social isolation and adjustment problems in young children. Child Development, 78, 1395–1404. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01072.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , Lerner, J. V. , & Lerner, R. M. (2010). Personal and ecological assets and academic competence in early adolescence: The mediating role of school engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 801–815. 10.1007/s10964-010-9535-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden‐Andersen, S. , Markiewicz, D. , & Doyle, A. (2009). Perceived similarity among adolescent friends: The role of reciprocity, friendship quality and gender. Journal of Early Adolescence, 29, 617–637. 10.1177/0272431608324372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm, K. , Jensen‐Campbell, L. , Rex‐Lear, M. , & Waldrip, A. (2006). Divided we fall: Children's friendships and peer victimization. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 23, 721–740. 10.1177/0265407506068260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maras, P. (2002). The ‘About me’ questionnaire. London, UK: University of Greenwich. [Google Scholar]

- Maras, P. , Brosnan, M. , Faulkner, N. , Montgomery, T. , & Vital, P. (2006). ‘They are out of control’: Self‐perceptions, risk‐taking and attributional style of adolescents with SEBDs. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 11, 281–298. 10.1080/13632750601043861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maras, P. , Moon, A. , & Zhu, L. (2012). Chinese and British adolescents’ academic self‐concept, social identity and behaviour in schools. BJEP Monograph Series II: Psychology and Antisocial Behaviours in Schools, 9, 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Maras, P. , Thompson, T. , Gridley, N. , & Moon, A. (2016). The ‘About Me’ questionnaire: Factorial structure and measurement invariance. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 36, 379–391. 10.1177/0734282916682909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marks, P. E. L. , Babcock, B. , Cillessen, A. H. N. , & Crick, N. R. (2013). The effects of participation rate on the internal reliability of peer nomination measures. Social Development, 22, 609–622. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00661.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meter, D. J. , & Card, N. A. (2016). Stability of children's and adolescents’ friendships: A meta‐analytic review. Merrill‐Palmer Quarterly, 62, 252–284. 10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.62.3.0252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb, A. F. , & Bagwell, C. L. (1995). Children's friendship relations: A meta‐analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 306–347. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J. G. , & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29, 611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Pederson, S. , Vitaro, F. , Barker, E. D. , & Borge, A. I. H. (2007). The timing of middle‐childhood peer rejection and friendship: Linking early behavior to early‐adolescent adjustment. Child Development, 78, 1037–1051. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raboteg‐Savic, Z. , & Sakic, M. (2014). Relations of parenting styles and friendship quality to self‐esteem, life‐satisfaction and happiness in adolescents. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 9, 749–765. 10.1007/s11482-013-9268-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, K. H. , Bukowski, W. M. , & Bowker, J. C. (2015). Children in peer groups In Lerner R. M. (Ed). Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (pp. 321–412). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 10.1002/9781118963418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, K. H. , Bukowski, W. M. , & Parker, J. G. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups In Eisenberg N. (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology. Volume 3: Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 571–645). Hoboken, NJ; John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, K. D. , Hammen, C. , & Burge, D. (1995). Cognitive representations of self, family, and peers in school‐age children: Links with social competence and sociometric status. Child Development, 66, 1385–1402. 10.1111/1467-8624.ep9510075269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakyi, K. S. , Surkan, P. J. , Fombonne, E. , Chollet, A. , & Melchior, M. (2015). Childhood friendships and psychological difficulties in young adulthood: An 18‐year follow‐up study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 24, 815–826. 10.1007/s00787-014-0626-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, D. , Gorman, A. , Dodge, K. , Bates, J. , & Pettit, G. (2008). Friendships with peers who are low or high in aggression as moderators of the link between peer victimization and declines in academic functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 719–730. 10.1007/s10802-007-9200-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, D. , Lansford, J. E. , Dodge, K. A. , Petit, G. S. , & Bates, J. E. (2015). Peer victimization during middle childhood as a lead indicator of internalizing problems and diagnostic outcomes in late adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44, 393–404. 10.1080/15374416.2014.881293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P. E. (2011). Commentary: Mediation analysis, causal process, and cross‐sectional data. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46, 852–860. 10.1080/00273171.2011.606718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaten, C. D. , Ferguson, J. K. , Allen, K.‐A. , Brodrick, D.‐V. , & Waters, L. (2016). School belonging: A review of the history, current trends, and future directions. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33, 1–15. 10.1017/edp.2016.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talmon, A. , & Ginzburg, K. (2017). Between childhood maltreatment and shame: The roles of self‐objectification and disrupted body boundaries. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41, 325–337. 10.1177/0361684317702503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tu, K. M. , Erath, S. A. , & Flanagan, K. A. (2012). Can socially adept friends protect peer‐victimized early adolescents against lower academic competence? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 33, 24–30. 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vandell, D. , & Hembree, S. (1994). Social status and friendship: Independent contributors to children's social and academic adjustment. Merrill‐Palmer Quarterly, 40, 461–477. [Google Scholar]

- Waldrip, A. M. , Malcolm, K. T. , & Jensen‐Campbell, L. A. (2008). With a little help from your friends: The importance of high quality friendships on early adolescent adjustment. Social Development, 14, 832–852. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00476.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. , & Fletcher, A. C. (2017). The role of interactions with teachers and conflict with friends in shaping school adjustment. Social Development, 26, 545–559. 10.1111/sode.12218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer‐Gembeck, M. J. , Waters, A. M. , & Kindermann, T. (2010). A social relations analysis of liking for and by peers: Associations with gender, depression, peer perception, and worry. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 69–81. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]