Abstract

Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy (Li-ESWT) is a form of energy transfer that is of lower intensity (<0.2 mJ/mm2) relative to traditional Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL) used for management of urinary stones. At this intensity and at appropriate dosing energy transfer is thought to induce beneficial effects in human tissues. The proposed therapeutic mechanisms of action for Li-ESWT include neovascularization, tissue regeneration, and reduction of inflammation. These effects are thought to be mediated by enhanced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Upregulation of chemoattractant factors and recruitment/activation of stem/progenitor cells may also play a role. Li-ESWT has been studied for management of musculoskeletal disease, ischemic cardiovascular disorders, Peyronie’s Disease, and more recently erectile dysfunction (ED). The underlying mechanism of Li-ESWT for treatment of ED is incompletely understood. We summarize the current evidence basis by which Li-ESWT is thought to enhance penile hemodynamics with an intention of outlining the fundamental mechanisms by which this therapy may help manage ED.

Introduction

Shock waves may be conceptualized as acoustic waves that propagate through a medium (such as human tissues) and carry energy 1. The angle of the waves generated by a shock wave device may be adjusted so that the energy they carry converges on a single point in space. 2 While the energy of each individual wave is low, when brought to a point of confluence the summation of each individual wave’s energy may produce an effect on a target. Hence, it is possible to transmit energy to a remote anatomical target with minimal effect on the tissue located between the shockwave generator and the target. This principle is the foundation of Extracorporeal Shockwave Lithotripsy (ESWL) used to fragment renal and ureteral stones.

The use of ESWL requires transfer of a substantial amount of energy in order to fracture a stone. Although the principle medical utilization of external shock wave energy has historically been towards fracture of stones, a counterintuitive osteoblastic response was observed in animal studies 3. This work led to clinical application of Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy (Li-ESWT) to numerous orthopedic disorders,4 including healing of fractures, 5 pain management, and treatment of arthritis6.

Shock waves may also be applied to soft tissues, wherein they may induce a cascade of biological reactions. The energy transfer of Li-ESWT occurs via mechanotransduction7, micro-cavitation8, and thermodynamic effects. The dominant effect of low-intensity shock waves is thought to be mechanotransduction. Rather than inducing damage in the target, Li-ESWT may induce tissue healing and angiogenesis9. This effect has led to application of Li-ESWT for treatment of muscular disorders10, cardiac disease11,12, non-healing wounds13,14, and Peyronie’s Disease (PD) 15. 16

Unfortunately, Li-ESWT has not shown reliable and clinically relevant changes in PD 17. Despite this disappointing result, sexual medicine specialists have remained interested in this technology as a means to manage erectile dysfunction (ED)18, 19. Promising clinical results in the initial study of Vardi et al20 and subsequent studies from other centers have generated marked interest in this novel ED treatment 21. Despite this high level of interest, the underlying mechanism of action for Li-ESWT in management of ED remains unclear. Existing studies suggest that the effects of Li-ESWT on penile tissue include cell proliferation, enhanced cell survival, mitigation of fibrosis/inflammation, and recruitment/activation of endogenous stem cells 22. The net result may be angiogenesis, improved wound healing, and regeneration of muscle and nerve tissue.23-25

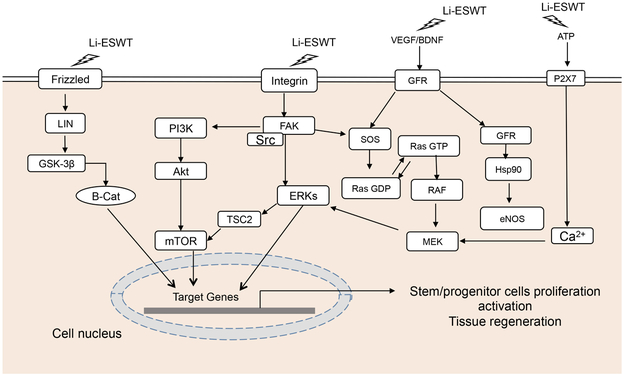

Li-ESWT regulates the cellular signaling transduction, affects the transcription and modification of intracellular proteins.24 Specific cellular processes/molecules modulated by Li-ESWT include Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK)3, Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)23, Wnt26, ATP/P2X726, Protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase / activated transcription factor (PERK/ATF)27,Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)28. We will elaborate on these molecular mechanisms in the following (Figure 1).

Fig 1. Cellular signaling pathways modulated by Low-intensity Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (Li-ESWT).

Li-ESWT: Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy; Frizzled: receptor of WNT; BDNF: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; GSK-3β: Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta; β-Cat: beta-catenin; PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; Akt: Protein kinase B (PKB), also known as Akt; Src: Src is short for sarcoma, a Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src; TSC2: Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 2; GFR: growth factor receptor; RAS: molecules of MAPK/ERK pathway; RAF: molecules of MAPK/ERK pathway; MEK: mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; mTORC1:mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; FAK: Focal Adhesion Kinase; VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor ; SOS: Son of Sevenless

Characteristics of medical shockwaves

Shock waves are characterized by high peak pressures (up to 100 mpa or higher), rapid pressure rise (<10 ns), short duration (<10 ms) and wide frequency range7. Unlike ultrasonic waves (which consist of periodic oscillations with limited bandwidth), shock waves consist of a single predominantly positive pressure pulse followed by a relatively small stretched wave component2. Shock waves used for biomedical purposes are generated in a fluid medium using an electro-hydraulic, piezoelectric, or electromagnetic generator. 29 Generated shockwaves are then directed to the target by a focusing unit. 2 It is unclear on whether the method of shock wave generation is germane to ultimate tissue effects; however, the intensity of the generated wave is likely to be highly relevant.

Shock waves and Mechanotransduction

Li-ESWT exerts a mechanical force on cell membranes and contents. Mechanotransduction is the term for cellular processes by which mechanical stimuli are converted into biochemical signals. Short-term reactions include increased intracellular tension, cellular adhesion, and cellular migration. Long-term effects of Li-ESWT are thought to be mediated through multiple overlapping and crosstalk signaling pathways (e.g. protein synthesis/secretion, structural reorganization, proliferation, vitality)30.

Mechanotransduction consists of several discrete phases: 31

Phase 1: the mechanocoupling phase, wherein wave energy is converted into a mechanical signal in the vicinity of the cell;

Phase 2: biochemical coupling, wherein the mechanical signal induces activation of biochemical pathways, leading to activation of transcription factors and/or changes in the action of cellular pathways such as calcium-dependent pathways, mitogen-activated protein kinases, and second messenger systems;

Phase 3: signal transmission, where the biochemical signal may be propagated between cells;

Phase 4: cellular response.

A number of specific elements are thought to play a role in mechanotransduction. These include: 7, 30

1) Extracellular matrix proteins (e.g fibronectin), which can transmit mechanical forces to cells;

2) Stretch-activated ion channels, which allow influx of calcium and other ions with membrane strain;

3) The glycocalyx, which responds to fluid shear stress on the cell membrane of endothelial cells and mediates endothelial permeability and action;

4) Cell-cell junctional receptors and cell-matrix focal adhesions, which may induce paracrine or ionic effects;

5) Cytoskeletal components, which may altering binding affinity and/or concentration for a particular molecule/signaling pathway;

6) The nucleus, the membrane of which is known to contain mechanosensors;

7) The cytoplasm, compression of which by a mechanical force may alter the effective concentration of autocrine and paracrine signaling molecules such as caveloae and membranes of organelles;

8) The mitochondria, which are affected by shock waves that induce changes in ATP production.

Cellular membranous signaling pathways modulated by Li-ESWT

a). Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) cellular signaling pathway

Integrin is a transmembrane receptor that facilitates cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesion and also plays a role conducting signals from the extracellular matrix into the cytoplasm 32 Integrin activates signal transduction pathways that regulate the cell cycle, organization of the intracellular cytoskeleton, and movement of new receptors to the cell membrane. Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) is a non-receptor cytosolic protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) with a central catalytic domain flanked by large N- and C-terminal domains. FAK indirectly localizes to sites of integrin-receptor clustering through interactions with integrin-associated proteins33. FAK is a central mediator of integrin signaling as well as an important part of several other signal pathways including those that influence cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis 34.

Low-energy shock waves interact with integrin and activate FAK by phosphorylation mediated by integrin α5 and β1, thereby triggering a series of cellular signaling and related biological changes which are known to be relevant to osteoblast adhesion and migration3. One of these downstream effects is phosphorylation of Tyrosine 397, the major autophosphorylation site of FAK; this response is known to play a role in cell migration35, 36. Additional Li-ESWT-mediated effects on FAK include translocation to focal adhesions and enhancement of phosphorylation of paxillin. Mechanical forces also induce focal adhesion maturation and α-actin redistribution to focal cellular adhesions.

The mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1(mTORC1) is regulated by FAK phosphorylation in the context of Li-ESWT mediated mechanoconduction. Li-ESWT induces mTORC1 phosphorylation and subcellular translocation, which in turn leads to mTORC1 mediated control of cell proliferation37.

The FAK mediated effects that are thought to be most relevant to management of ED include proliferation and migration of cells that restore endothelial and smooth muscle integrity in penile vascular tissues. The majority of cellular signaling pathways relevant in Li-ESWT modulation of ED appear to work via FAK.

b). Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) cellular signaling pathway

The mechanical effects of shock waves on cells may result in changes in membrane activity. This may include opening of Pannexin-1 (PANX1) channel to release ATP23. ATP activates p38MAPK and Mek1 / 2-Erk1 / 2 signaling pathway, which lead to cell proliferation in vitro and enhanced wound healing in vivo 23. The role of ATP in mediating shock wave induced cell proliferation was demonstrated by studies in which ATP was degraded by apyrase or the P2Y receptor blocker suramin; in the presence of these inhibitors, the cellular proliferative effect of shock wave therapy was eliminated. Similar blockade of shock wave induced cell proliferation was demonstrated by inhibition of Mek1 / 2 (via U0126 in vitro and GSK1120212 in vivo) 23.

The Erk 1/2 signaling pathway may also be activated by Li-ESWT via stimulation of the growth factor receptor and a seven-domain G-protein coupled receptor. This cascade activates Ras, which in turn interacts with integrins via the adaptor protein SHC and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Son of Sevenless (SOS). Integrin-mediated phosphorylation of Erk 1/2 is also associated with enhanced expression of VEGF and increased eNOS expression,38 the net result of which is endothelial regeneration and angiogenesis through VEGFR2-Akt-eNOS39. Given the central importance of vascular integrity to penile erection, restoration of endothelial action is a likely mediator of ESWT-induced improvement in penile erection.

c). Wnt/β-catenin cellular signaling pathway

The Wnt signaling pathway, a highly conserved sequence across taxa, is a complex network of protein action that is relevant for embryonic development, neoplasia, and the normal physiological processes of adult animals40. The net effects of the Wnt pathway are both autocrine and paracrine.

Three Wnt signaling pathways have been identified: canonical Wnt pathway, noncanonical Wnt/planar cell polarity pathway (PCP), and noncanonical Wnt/calcium pathway. The Wnt/PCP pathway regulates the cytoskeleton to control cell shape. The noncanonical Wnt/calcium pathway regulates intracellular calcium ion concentration 41. All three of these Wnt signaling pathways are activated by the binding of Wnt protein ligands to the Frizzled, a G-protein coupled receptor. Frizzled conducts signals to intracellular Dishevelled42 (Dsh), a cytosolic phosphorylated protein which is involved in both the calcium and non-calcium Wnt signaling pathways43.

Binding of Wnt to the Frizzled Receptor recruits DVL to the membrane, providing a site for Axin and GSK3β to bind and phosphorylate LRP5 / 6 (transmembrane LDL receptor-associated protein), thereby preventing the constitutive form of β-catenin degradation. After stabilized and accumulated, β-Catenin enter the nucleus and binds to TCF to initiate downstream gene transcription. In the absence of WNT proteins, β-catenin will be phosphorylated on the complex of β-catenin and a tertiary complex formed by axin, APC, CK1α and GSK 3β44. β-catenin is phosphorylated by a complex of kinases at a set of conserved Ser and Thr residues at its amino terminus45. The phosphorylated form of β-catenin is recognized by E3 ubiquitin ligase (β-TrCP) and then targeted for proteasomal degradation.

One of the potential therapeutic mechanisms of Li-ESWT is smooth muscle proliferation. A number of studies have demonstrated that Li-ESWT enhances activation of Wnt signalin/β-catenin with a peak increase 2 hours post-treatment. Shock wave mediated activation of Wnt-β-catenin has been shown to activate MyoD/Myf5 in vitro, which induces muscle cell differentiation46.

Shock wave induced activation of Wnt/β-catenin has also been shown to induce differentiation of mouse Neuronal stem cells (NSCs) in vitro26. Inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by Dkk-1 45 delayed NSC maturation by reducing β-tubulin III expression in animals treated with Li-ESWT. These findings provide further evidence that Li-ESWT treatment regulates NSCs differentiation via Wnt/β-catenin signaling47.

Cellular signaling related to Organelle modulated by Li-ESWT

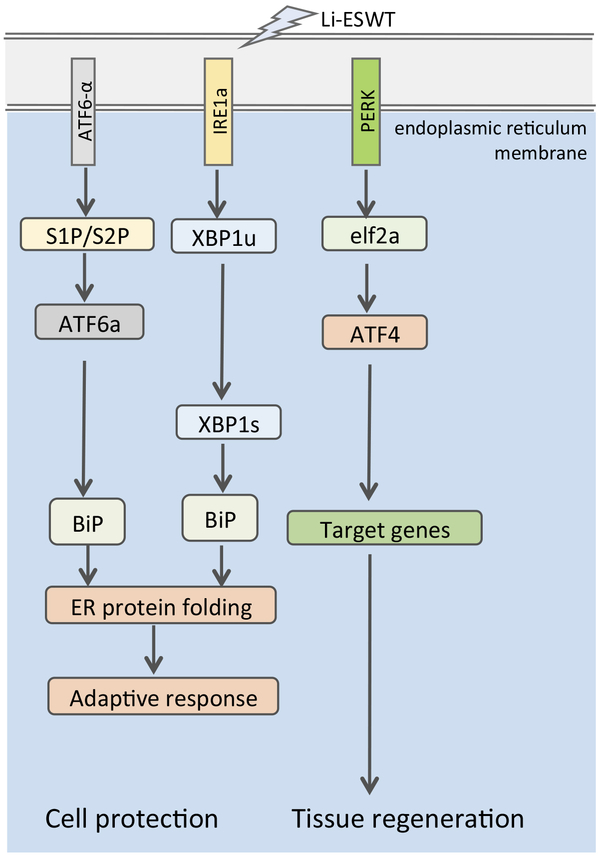

a). Unfolded Protein Response signaling pathway

The endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) response is a ubiquitous cellular pathway that directs proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol or nucleus. Protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) is one of the major transducers of the ERS response. PERK directly phosphorylates the alpha-subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α), resulting in translational attenuation. Phosphorylated eIF2α specifically promotes translation of activated transcription factor 4 (ATF4), which is known to be an important transcription factor regulating osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Mechanical forces are known to activate the ERS-mediated PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 signaling pathway and thus modulate the differentiation of osteoblasts48. In addition to ERS-mediated effects on bone metabolism, Li-ESWT27 increases myotube formation in muscle-derived stem cells (MDSCs) via the PERK pathway. This process of myogenesis is thought to play a role in regeneration of penile smooth muscle and subsequent improvement in penile erection.

Li-ESWT activates the protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum (ER) kinase (PERK) pathway by increasing the phosphorylation levels of PERK, eukaryotic initiation factor 2a (eIF2α), and activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) in an energy-dependent manner. GSK2656157—an inhibitor of PERK—effectively blocks the effect of Li-ESWT on the phosphorylation of PERK, eIF2α, and the expression of ATF4. Furthermore, silencing ATF4 dramatically attenuates the effect of Li-ESWT on the expression of BDNF but has no effect on hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)1α or glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) in Schwann cells. It is apparent that Li-ESWT stimulates the expression of BDNF through activation of PERK/ATF4 signaling pathway49. (Fig 2)

Fig 2. Low-intensity Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Modulated Unfolded Protein Response (UPR).

IRE1a: inositol-requiring enzyme 1α; S1P: Sphingosine-1-phosphate; S2P: Sphingosine-2-phosphate; ATF: activated transcription factor; BiP: Immunoglobulin heavy-chain-binding protein; XBP1u: un-spliced X-box binding protein 1; XBP1s: spliced X-box binding protein 1; PERK: Protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase; eIF2: eukaryotic initiation factor 2

b). ATP/P2X7 pathway

Activation of the ATP/P2X7 pathway may also be of benefit in treatment of ED. Osteoblasts express several P2 receptor subtypes, ATP can activate P2 receptors in osteoblasts and increases intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. P2 signaling also regulates the activity of ERK1/2 and P38/MAPK signaling pathways and c-fos expression in osteoblasts. Stimulation of the P2X7 receptor activation can lead to osteoblast differentiation and enhancement of cell function for bone formation and remodeling.

The P2X7 receptor is the most abundantly expressed ionic subtype, and there is increasing evidence that human osteoblasts express the P2X7 receptor. Based on this evidence, some researchers have confirmed that shock waves may lead to the release of ATP and activation of P2X7 receptors. In addition, ATP can activate p38/MAPK, which plays an important role in regulating the differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts. P38/MAPK activation has also been shown to induce the expression of c-fos and c-Jun50. In this study shockwave treatment did not significantly inhibit cell survival (viability > 95%) if the dose was restricted to 200 or fewer pulses. Cell survival declines in a dose dependent fashion as the number of shocks exceeds 20051.

Cellular signaling related to Growth factor modulated by Li-ESWT: BDNF cellular signaling pathway

BDNF supports the survival of neurons and promotes the growth and differentiation of new neurons. BDNF has two major receptors: the pan-NT receptor p75 (p75NTR) and the tropomyosin-associated receptor kinase B (TrkB). P75 NTR has many functions such as differentiation, cell survival, and cell death signals. Binding of BDNF to TrkB triggers activation of downstream signaling pathways such as RAS/MAPK, RAP/MAPK, PI3K/AK, and phosphoinositide phospholipase C (PLC gamma) pathways. These pathways lead to cell survival, differentiation, synapse formation and plasticity 52.

Expression of BDNF increases markedly 3 days after nerve injury. After that, the expression of BDNF decreases sharply and reaches basal level 10 days after the injury. Treatment with repeated Li-ESWT increased expression of BDNF in the penis at a level that was maintained up to 26 days after nerve injury49. This prolonged expression is likely to sustain neurotrophic healing beyond what can be expected naturally and without intervention.

The mechanism of Li-ESWT mediated BDNF activation was studied in RT4-D6P2T Schwann cells and found to be related to activation of PERK/ATF4. The PERK blocker GSK265615753 reduced Li-ESWT mediated eIF2α phosphorylation and downstream target gene ATF4 expression. In this context expression of BDNF was also significantly reduced49.

Other studies show that Li-ESWT induces MSCs to express VEGF, though the underling mechanism is not well understood. VEGF in turn upregulates the PI3K / AKT /mTOR pathway, which induces autophagy. Autophagy and apoptosis assays indicate that Li-ESWT activates autophagy in penile tissue and effectively reduces apoptosis. BDNF is also associated with VEGF expression54. Knockdown of BDNF significantly reduces VEGF expression and angiogenesis in vivo55. There are data supporting the contention that Li-ESWT mediated increases in BDNF may also enhance VEGF expression in MSCs. Similar effects (BDNF mediated enhancement of VEGF signaling) have been reported in MSC treated with Li-ESWT.56.

Perspectives

Li-ESWT is a non-invasive and promising physical method for regenerative medicine. Numerous animal models of erectile dysfunction indicate that Li-ESWT may improve angiogenesis, activation of stem/progenitor cells, and muscle/nerve regeneration for remodeling penile erectile tissues. A robust and growing body of evidence supports the utility of Li-ESWT in ED; involved pathways include FAK3, ERK23, Wnt26, ATP/P2X726, PERK/ATF27, and BDNF28. Further research will be required to better define the key pathways relevant to erection function recovery and optimization of treatment protocols.

Acknowledgments:

This publication was supported by NIDDK of the National Institutes of Health under award number R56DK105097 and 1R01DK105097-01A1. It was also supported by Army, Navy, NIH, Air Force, VA and Health Affairs to support the AFIRM II effort, under Award number W81XWH-13-2-0052. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviation

- ATF

activated transcription factor

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- Dsh

Dishevelled

- ECM

cell-extracellular matrix

- ED

erectile dysfunction

- eIF2

eukaryotic initiation factor 2

- ERK

Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase

- ERS

endoplasmic reticulum stress

- ESWL

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy

- FAK

Focal Adhesion Kinase

- GDNF

glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- Li-ESWT

Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy

- LRP

LDL receptor-associated protein

- MDSCs

muscle-derived stem cells

- mTORC1

mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1

- NSCs

Neuronal stem cells

- p75NTR

pan-NT receptor p75

- PANX1

Pannexin-1

- PCP

Planar cell polarity pathway

- PD

Peyronie’s Disease

- PERK

Protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

- PTK

protein tyrosine kinase

- SOS

Son of Sevenless

- TrkB

tropomyosin-associated receptor kinase B

- UPR

Unfolded Protein Response

- VEGF

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

References

- [1].Lu Z, Lin G, Reed-Maldonado A, Wang C, Lee YC, Lue TF. Low-intensity Extracorporeal Shock Wave Treatment Improves Erectile Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. European urology. 2017;71: 223–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chung E, Wang J. A state-of-art review of low intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy and lithotripter machines for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Expert review of medical devices. 2017; 14: 929–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Xu JK, Chen HJ, Li XD, et al. Optimal intensity shock wave promotes the adhesion and migration of rat osteoblasts via integrin beta1-mediated expression of phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287: 26200–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang CJ. An overview of shock wave therapy in musculoskeletal disorders. Chang Gung medical journal. 2003;26: 220–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kertzman P, Csaszar NBM, Furia JP, Schmitz C. Radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy is efficient and safe in the treatment of fracture nonunions of superficial bones: a retrospective case series. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2017; 12: 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Li W, Pan Y, Yang Q, Guo ZG, Yue Q, Meng QG. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A retrospective study. Medicine. 2018;97: e11418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].d'Agostino MC, Craig K, Tibalt E, Respizzi S. Shock wave as biological therapeutic tool: From mechanical stimulation to recovery and healing, through mechanotransduction. International journal of surgery. 2015;24: 147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ohl SW, Klaseboer E, Khoo BC. Bubbles with shock waves and ultrasound: a review. Interface focus. 2015;5: 20150019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rassweiler JJ, Knoll T, Kohrmann KU, et al. Shock wave technology and application: an update. European urology. 2011;59: 784–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hazan-Molina H, Reznick AZ, Kaufman H, Aizenbud D. Periodontal cytokines profile under orthodontic force and extracorporeal shock wave stimuli in a rat model. Journal of periodontal research. 2015;50: 389–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Becker M, Goetzenich A, Roehl AB, et al. Myocardial effects of local shock wave therapy in a Langendorff model. Ultrasonics. 2014;54: 131–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yang P, Guo T, Wang W, et al. Randomized and double-blind controlled clinical trial of extracorporeal cardiac shock wave therapy for coronary heart disease. Heart and vessels. 2013;28: 284–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hayashi D, Kawakami K, Ito K, et al. Low-energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy enhances skin wound healing in diabetic mice: a critical role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Wound repair and regeneration : official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society. 2012;20: 887–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cooper B, Bachoo P. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the healing and management of venous leg ulcers. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018;6: CD011842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fojecki GL, Tiessen S, Osther PJ. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) in urology: a systematic review of outcome in Peyronie's disease, erectile dysfunction and chronic pelvic pain. World journal of urology. 2017;35: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yafi FA, Pinsky MR, Sangkum P, Hellstrom WJ. Therapeutic advances in the treatment of Peyronie's disease. Andrology. 2015;3: 650–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hatzichristodoulou G, Meisner C, Gschwend JE, Stenzl A, Lahme S. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy in Peyronie's disease: results of a placebo-controlled, prospective, randomized, single-blind study. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10: 2815–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Abu-Ghanem Y, Kitrey ND, Gruenwald I, Appel B, Vardi Y. Penile low-intensity shock wave therapy: a promising novel modality for erectile dysfunction. Korean journal of urology. 2014;55: 295–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Clavijo RI, Kohn TP, Kohn JR, Ramasamy R. Effects of Low-Intensity Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy on Erectile Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The journal of sexual medicine. 2017;14: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Vardi Y, Appel B, Jacob G, Massarwi O, Gruenwald I. Can low-intensity extracorporeal shockwave therapy improve erectile function? A 6-month follow-up pilot study in patients with organic erectile dysfunction. European urology. 2010;58: 243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Burnett AL, Nehra A, Breau RH, et al. Erectile Dysfunction: AUA Guideline. The Journal of urology. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lin G, Reed-Maldonado AB, Wang B, et al. In Situ Activation of Penile Progenitor Cells With Low-Intensity Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy. The journal of sexual medicine. 2017; 14: 493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Weihs AM, Fuchs C, Teuschl AH, et al. Shock wave treatment enhances cell proliferation and improves wound healing by ATP release-coupled extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289: 27090–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Xin ZC, Xu YD, Lin G, Lue TF, Guo YL. Recruiting endogenous stem cells: a novel therapeutic approach for erectile dysfunction. Asian journal of andrology. 2016; 18: 10–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shan HT, Zhang HB, Chen WT, et al. Combination of low-energy shock-wave therapy and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation to improve the erectile function of diabetic rats. Asian journal of andrology. 2017;19: 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang J, Kang N, Yu X, Ma Y, Pang X. Radial Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Enhances the Proliferation and Differentiation of Neural Stem Cells by Notch, PI3K/AKT, and Wnt/beta-catenin Signaling. Scientific reports. 2017;7: 15321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wang B, Zhou J, Banie L, et al. Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy promotes myogenesis through PERK/ATF4 pathway. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2018;37: 699–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zou ZJ, Liang JY, Liu ZH, Gao R, Lu YP. Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy for erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy: a review of preclinical studies. International journal of impotence research. 2018;30: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dietz-Laursonn K, Beckmann R, Ginter S, Radermacher K, de la Fuente M. In-vitro cell treatment with focused shockwaves-influence of the experimental setup on the sound field and biological reaction. Journal of therapeutic ultrasound. 2016;4: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Jaalouk DE, Lammerding J. Mechanotransduction gone awry. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2009; 10: 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Huang C, Holfeld J, Schaden W, Orgill D, Ogawa R. Mechanotherapy: revisiting physical therapy and recruiting mechanobiology for a new era in medicine. Trends in molecular medicine. 2013; 19: 555–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Guan JL. Focal adhesion kinase in integrin signaling. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 1997; 16: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Guan JL, Shalloway D. Regulation of focal adhesion-associated protein tyrosine kinase by both cellular adhesion and oncogenic transformation. Nature. 1992;358: 690–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kurenova E, Xu LH, Yang X, et al. Focal adhesion kinase suppresses apoptosis by binding to the death domain of receptor-interacting protein. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24: 4361–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Owen JD, Ruest PJ, Fry DW, Hanks SK. Induced focal adhesion kinase (FAK) expression in FAK-null cells enhances cell spreading and migration requiring both auto- and activation loop phosphorylation sites and inhibits adhesion-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Pyk2. Molecular and cellular biology. 1999; 19: 4806–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sieg DJ, Hauck CR, Schlaepfer DD. Required role of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) for integrin-stimulated cell migration. Journal of cell science. 1999;112 (Pt 16): 2677–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lee FY, Zhen YY, Yuen CM, et al. The mTOR-FAK mechanotransduction signaling axis for focal adhesion maturation and cell proliferation. American journal of translational research. 2017;9: 1603–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hatanaka K, Ito K, Shindo T, et al. Molecular mechanisms of the angiogenic effects of low-energy shock wave therapy: roles of mechanotransduction. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2016;311: C378–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Holfeld J, Tepekoylu C, Blunder S, et al. Low energy shock wave therapy induces angiogenesis in acute hind-limb ischemia via VEGF receptor 2 phosphorylation. PloS one. 2014;9: e103982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lie DC, Colamarino SA, Song HJ, et al. Wnt signalling regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nature. 2005;437: 1370–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Thrasivoulou C, Millar M, Ahmed A. Activation of intracellular calcium by multiple Wnt ligands and translocation of beta-catenin into the nucleus: a convergent model of Wnt/Ca2+ and Wnt/beta-catenin pathways. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288: 35651–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Malbon CC. Frizzleds: new members of the superfamily of G-protein-coupled receptors. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 2004; 9: 1048–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Penton A, Wodarz A, Nusse R. A mutational analysis of dishevelled in Drosophila defines novel domains in the dishevelled protein as well as novel suppressing alleles of axin. Genetics. 2002;161: 747–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Pai SG, Carneiro BA, Mota JM, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway: modulating anticancer immune response. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2017;10: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chiurillo MA. Role of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in gastric cancer: An in-depth literature review. World journal of experimental medicine. 2015;5: 84–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Mattyasovszky SG, Langendorf EK, Ritz U, et al. Exposure to radial extracorporeal shock waves modulates viability and gene expression of human skeletal muscle cells: a controlled in vitro study. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2018; 13: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kang N, Zhang J, Yu X, Ma Y. Radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy improves cerebral blood flow and neurological function in a rat model of cerebral ischemia. American journal of translational research. 2017;9: 2000–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Yang SY, Wei FL, Hu LH, Wang CL. PERK-eIF2alpha-ATF4 pathway mediated by endoplasmic reticulum stress response is involved in osteodifferentiation of human periodontal ligament cells under cyclic mechanical force. Cellular signalling. 2016;28: 880–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wang B, Ning H, Reed-Maldonado AB, et al. Low-Intensity Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Enhances Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Expression through PERK/ATF4 Signaling Pathway. International journal of molecular sciences. 2017;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Burnstock G Purinergic signalling: Its unpopular beginning, its acceptance and its exciting future. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2012;34: 218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Qi B, Yu T, Wang C, et al. Shock wave-induced ATP release from osteosarcoma U2OS cells promotes cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of methotrexate. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR. 2016;35: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kowianski P, Lietzau G, Czuba E, Waskow M, Steliga A, Morys J. BDNF: A Key Factor with Multipotent Impact on Brain Signaling and Synaptic Plasticity. Cellular and molecular neurobiology. 2018;38: 579–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Axten JM, Romeril SP, Shu A, et al. Discovery of GSK2656157: An Optimized PERK Inhibitor Selected for Preclinical Development. ACS medicinal chemistry letters. 2013;4: 964–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Nakamura K, Martin KC, Jackson JK, Beppu K, Woo CW, Thiele CJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of TrkB induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression via hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in neuroblastoma cells. Cancer research. 2006;66: 4249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lin CY, Hung SY, Chen HT, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor increases vascular endothelial growth factor expression and enhances angiogenesis in human chondrosarcoma cells. Biochemical pharmacology. 2014;91: 522–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Zhu GQ, Jeon SH, Bae WJ, et al. Efficient Promotion of Autophagy and Angiogenesis Using Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy Enhanced by the Low-Energy Shock Waves in the Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction. Stem cells international. 2018;2018: 1302672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]