Abstract

Background

The benefits of chronic coronary total occlusion (CTO) percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are being questioned. The aim of this study was to assess the effects of CTO PCI on absolute myocardial perfusion, as compared with PCI of hemodynamically significant non‐CTO lesions.

Methods

Consecutive patients with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (≥50%) and a CTO or non‐CTO lesion, in whom [15O]H2O positron emission tomography was performed prior and after successful PCI, were included. Change in quantitative (hyperemic) myocardial blood flow (MBF), coronary flow reserve (CFR) and perfusion defect size (in myocardial segments) were compared between CTOs and non‐CTO lesions.

Results

In total 92 patients with a CTO and 31 patients with a non‐CTO lesion were included. CTOs induced larger perfusion defect sizes (4.51 ± 1.69 vs. 3.23 ± 2.38 segments, P < 0.01) with lower hyperemic MBF (1.30 ± 0.37 vs. 1.58 ± 0.62 mL·min−1·g−1, P < 0.01) and similarly impaired CFR (1.66 ± 0.75 vs. 1.89 ± 0.77, P = 0.17) compared with non‐CTO lesions. After PCI both hyperemic MBF and CFR increased similarly between groups (P = 0.57 and 0.35) to normal ranges with higher hyperemic MBF values in non‐CTO compared with CTO (2.89 ± 0.94 vs. 2.48 ± 0.73 mL·min−1·g−1, P = 0.03). Perfusion defect sizes decreased similarly after CTO PCI and non‐CTO PCI (P = 0.14), leading to small residual defect sizes in both groups (1.15 ± 1.44 vs. 0.61 ± 1.45 segments, P = 0.054).

Conclusions

Myocardial perfusion findings are slightly more hampered in patients with a CTO before and after PCI. Percutaneous revascularization of CTOs, however, improves absolute myocardial perfusion similarly to PCI of hemodynamically significant non‐CTO lesions, leading to satisfying results.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, positron emission tomography

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic coronary total occlusions (CTOs) are diagnosed in approximately one fifth of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).1 Due to historically low success rates, increased complication rates, and concerns regarding patient benefit, only the minority of patients with a CTO is referred for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).1, 2, 3 Recently, the development of the “hybrid approach”, an algorithm for treating CTOs in a most safe, effective, and efficient way, has resulted in high success and acceptable complication rates.4, 5 Ischemic burden comprising >10% of the left ventricle due to CAD holds prognostic relevance, and several studies have shown extensive ischemia to be present in nearly all patients with a CTO.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Therefore, next to symptom recognition and viability detection, ischemia detection forms one of the pillars in judicious patient selection for CTO PCI. Major reductions in ischemia can be achieved after CTO PCI, however, it is more conservatively employed compared with PCI of a non‐CTO lesion.12, 13, 14 [15O]H2O positron emission tomography (PET) is the gold standard for non‐invasive myocardial perfusion imaging, reflecting the composite of the epicardial as well as the microvascular bed, and enabling absolute quantification of myocardial perfusion.15 The aim of this study was to compare the effects of PCI among CTO versus non‐CTO lesions on quantitative myocardial blood flow (MBF) and perfusion defect size.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and participants

The study population consisted of consecutive prospectively recruited patients successfully treated with a clinically indicated PCI of a CTO (CTO group) or hemodynamically significant non‐CTO lesion (non‐CTO group) between 2012 and 2017 at the VU University Medical Center. Inclusion criteria were [15O]H2O PET imaging prior and after PCI, and a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, ≥50%) to guarantee viable myocardium at the vascular territory of the coronary lesion. Exclusion criteria were the occurrence of myocardial infarction (MI) or myocardial revascularization between the index (staged) PCI procedure and PET imaging post‐PCI, contraindications to adenosine and pregnancy. Patients with a CTO were selected from a dedicated program with two experienced CTO operators (PK and AN), in which ischemia‐ and viability testing is used for patient selection for CTO PCI. Patients in the non‐CTO group were selected from the previously published PACIFIC‐trial, comprising only patients without a cardiac history.15 The study was approved by the institutional Medical Ethics Review Committee and all patients provided written informed consent.

2.2. Angiographic characteristics

A CTO was defined as a luminal occlusion on invasive coronary angiography for an estimated time of ≥3 months with no or minimal contrast penetration through the lesion (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction [TIMI] flow grades 0–I).16 The Japanese CTO score (J‐CTO) was calculated and CTO PCI was performed according to the hybrid approach, using antegrade wire escalation (AWE), antegrade dissection and reentry (ADR), retrograde wire escalation (RWE), and retrograde dissection and reentry (RDR) techniques5, 17. A >90% diameter stenosis or fractional flow reserve (FFR) of ≤0.80 defined a hemodynamically significant non‐CTO lesion. In case of multivessel non‐CTO PCI, only the vessel with the worst lesion characteristics regarding stenosis severity or FFR value was included for analysis. Procedural success was defined as <30% diameter stenosis and TIMI flow grade III without any major side branch loss. Cardiac biomarkers were obtained if periprocedural MI was suspected, which was subsequently scored according to the Third Universal Definition of MI.18

2.3. Positron emission tomography

[15O]H2O PET perfusion scans were performed as described previously.9 Briefly, a dynamic emission scan was performed at rest followed by an identical scan during administration of intravenous adenosine (140 μ·kg−1·min−1). Coronary flow reserve (CFR) was calculated as the ratio of hyperemic to rest MBF. Perfusion defect size associated with a (non‐)CTO lesion was defined by the number of myocardial segments in which hyperemic MBF was below 2.3 mL·min−1·g−1 and <75% compared with hyperemic MBF in a normal reference vascular territory. The standardized 17‐segment model of the American Heart Association was used for left ventricular segmentation.19

2.4. Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are presented as mean values ± SD, whereas categorical variables are expressed as actual numbers, unless otherwise stated. Continuous variables were analyzed using the independent‐samples t test and paired‐samples t test in case of normally distributed data, and the Mann–Whitney U test and Wilcoxon signed‐rank test in case data was not normally distributed. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Fisher's Exact Test for binary data and the Chi‐squared test for ordinal data. Comparisons between groups in MBF and perfusion defect size were analyzed using a linear regression analysis adjusted for age and gender. A level of P < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0, Chicago, IL).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient population

Clinical characteristics of the included 92 patients with a CTO and 31 patients with a hemodynamically significant non‐CTO lesion are listed in Table 1. Patients with a CTO had more cardiac risk factors (2.6 ± 1.2 vs. 1.8 ± 1.1; P = 0.01) as compared with patients with a non‐CTO lesion. As a result of different patient cohorts, only subjects with a CTO had suffered before from major cardiac events, including prior MI in the CTO territory in 25% of patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| CTO (n = 92) | Non‐CTO (n = 31) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62 ± 10 | 57 ± 9 | 0.02 |

| Male | 74 (80) | 26 (84) | 0.79 |

| Body mass index (kg∙m−2) | 27.8 ± 4.0 | 26.5 ± 3.5 | 0.11 |

| Previous MI | 33 (36) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Previous MI in TV area | 23 (25) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Q‐wave | 8 (9) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Q‐wave in TV area | 6 (7) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Previous PCI | 64 (70) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Post‐CABG | 10 (11) | 0 (0) | NA |

| CAD risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 56 (61) | 8 (26) | <0.01 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 47 (51) | 12 (39) | 0.30 |

| Current smoking | 28 (30) | 5 (16) | 0.16 |

| History of smoking | 40 (44) | 18 (58) | 0.21 |

| Family history CAD | 44 (48) | 17 (55) | 0.54 |

| Diabetes | 25 (27) | 2 (7) | 0.02 |

| Number of CAD risk factors | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 0.01 |

| Medication | |||

| Aspirin | 87 (95) | 30 (97) | 1.00 |

| Dual anti‐platelets | 60 (65) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| Anticoagulant | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.33 |

| Statins | 79 (86) | 25 (81) | 0.57 |

| Beta‐blockers | 76 (83) | 21 (68) | 0.13 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 24 (26) | 9 (29) | 0.82 |

| Long‐acting nitrates | 25 (27) | 3 (10) | 0.05 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Free of symptoms | 15 (16) | 1 (3) | 0.07 |

| Stable angina | 47 (51) | 22 (71) | 0.06 |

| Dyspnea on exertion | 16 (17) | 1 (3) | 0.07 |

| Atypical symptoms | 11 (12) | 7 (23) | 0.15 |

| Unstable angina | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Non‐ST elevation MI | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CAD, coronary artery disease; CTO, chronic coronary total occlusion; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not applicable; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TV, target vessel.

3.2. Angiographic characteristics

A CTO was located in the right coronary artery in 70% of patients (Table 2). The J‐CTO score was 0–1, 2, and ≥3 in 46, 29, and 25% of CTO lesions, and the successful crossing technique was AWE, ADR, RWE, and RDR in 44, 23, 9, and 25% of patients, respectively. Non‐CTO lesions were predominantly located in the left anterior descending artery (LAD, 68%). Three of these lesions had a >90% diameter stenosis and the remaining target lesions were determined hemodynamically significant with a mean FFR of 0.55 ± 0.19. The number of vessel disease and the number of vessel PCI was equally distributed between groups. Staged PCI was performed in two patients with a CTO in which another non‐CTO lesion was treated first, and in none of the patients in the non‐CTO group. Periprocedural MI occurred in six patients treated by CTO PCI (four times after an RDR technique and two times after an ADR technique) due to the loss of a minor right ventricular branch (in five patients) or a temporarily obstructed side branch during subintimal wiring (in one patient).

Table 2.

Angiographic characteristics

| CTO (n = 92) | Non‐CTO (n = 31) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target vessel | <0.01 | ||

| Right coronary artery | 64 (70) | 3 (10) | |

| Left anterior descending artery | 16 (17) | 21 (68) | |

| Left circumflex coronary artery | 12 (13) | 7 (23) | |

| Number of vessel disease | 0.74 | ||

| Single vessel | 62 (67) | 21 (68) | |

| Two vessel | 25 (27) | 7 (23) | |

| Three vessel | 5 (5) | 3 (10) | |

| Number of vessel PCI | 0.60 | ||

| Single vessel | 73 (79) | 22 (71) | |

| Two vessel | 16 (17) | 7 (23) | |

| Three vessel | 3 (3) | 2 (7) |

Values are n (%). P values indicate the overall difference between groups.Abbreviations: CTO, chronic coronary total occlusion; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

3.3. Recovery after CTO PCI

Rest MBF in the myocardial area subtended by the CTO was 0.86 ± 0.25 and did not change after PCI (p = .95) (Table 3). In contrast, hyperemic MBF significantly increased after PCI (from 1.30 ± 0.37 to 2.48 ± 0.73 mL·min−1·g−1; P < 0.01), as did the CFR (from 1.66 ± 0.75 to 3.03 ± 1.05; P < 0.01). The perfusion defect size significantly decreased from 4.51 ± 1.69 to 1.15 ± 1.44 segments (P < 0.01). In remote areas, hyperemic MBF was 2.69 ± 0.69 and 2.70 ± 0.73 mL·min−1·g−1 at baseline and follow‐up (P < 0.01 and P = 0.048 as compared with the CTO area), respectively. Additional analyses demonstrated that all PET perfusion results were comparable (P > 0.05) between CTO patients with (n = 23) and without (n = 69) documented prior MI in the myocardium subtended by the CTO. In addition, the above mentioned MBF indices and residual perfusion defect size after CTO PCI did not differ between patients with and without periprocedural MI (all comparisons P > 0.05). Successful intraplaque crossing and stenting (AWE or RWE) resulted in relatively higher hyperemic MBF values after PCI than with a successful dissection and reentry (DR) technique (2.67 ± 0.76 vs. 2.28 ± 0.65 mL·min−1·g−1; P = 0.02), whilst MBF during rest (P = 0.56), CFR (P = 0.12) and the residual perfusion defect size (P = 0.25) were comparable. At follow‐up, residual ischemia was present in the CTO area in one patient due to a significant stenosis distal to the (former) CTO lesion, and two other patients had residual ischemia in a non‐target vessel. After follow‐up PET imaging and clinical evaluation, these patients were treated by additional PCI.

Table 3.

Quantitative MBF in patients treated with CTO PCI vs non‐CTO PCI

| CTO (n = 92) | Non‐CTO (n = 31) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rest MBF pre‐PCI | 0.86 ± 0.25 | 0.83 ± 0.15 | 0.52 |

| Rest MBF post‐PCI | 0.86 ± 0.22 | 0.97 ± 0.29 | 0.03 |

| P value | 0.95 | <0.01 | |

| Δ rest MBF | 0.00 ± 0.23 | 0.13 ± 0.23 | <0.01 |

| Hyperemic MBF pre‐PCI | 1.30 ± 0.37 | 1.58 ± 0.62 | <0.01 |

| Hyperemic MBF post‐PCI | 2.48 ± 0.73 | 2.89 ± 0.94 | 0.03 |

| P value | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Δ hyperemic MBF | 1.18 ± 0.68 | 1.31 ± 1.07 | 0.57 |

| CFR pre‐PCI | 1.66 ± 0.75 | 1.89 ± 0.77 | 0.17 |

| CFR post‐PCI | 3.03 ± 1.05 | 3.10 ± 0.79 | 0.94 |

| P value | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Δ CFR | 1.37 ± 1.12 | 1.21 ± 0.97 | 0.35 |

Values are mean ± SD. MBF per mL·min−1·g−1. Outcomes are calculated using a linear regression analysis adjusted for age and gender.Abbreviations: Δ, change in MBF; CFR, coronary flow reserve; CTO, chronic coronary total occlusion; MBF, myocardial blood flow; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

3.4. Recovery after non‐CTO PCI

Rest MBF (from 0.83 ± 0.15 to 0.97 ± 0.29 mL·min−1·g−1; P < .01), hyperemic MBF (from 1.58 ± 0.62 to 2.89 ± 0.94 mL·min−1·g−1; P < 0.01) and CFR (from 1.89 ± 0.77 to 3.10 ± 0.79; P < 0.01) in the myocardial area subtended by non‐CTO lesions increased after PCI. The perfusion defect size was reduced from 3.23 ± 2.38 to 0.61 ± 1.45 segments (P < 0.01). In remote areas, hyperemic MBF was 2.82 ± 0.69 and 3.05 ± 0.92 mL·min−1·g−1 at baseline and follow‐up (P < 0.01 and p = .51 as compared with the non‐CTO lesion area), respectively. In none of the patients there was a clinical indication for re‐invasive coronary angiography after follow‐up imaging.

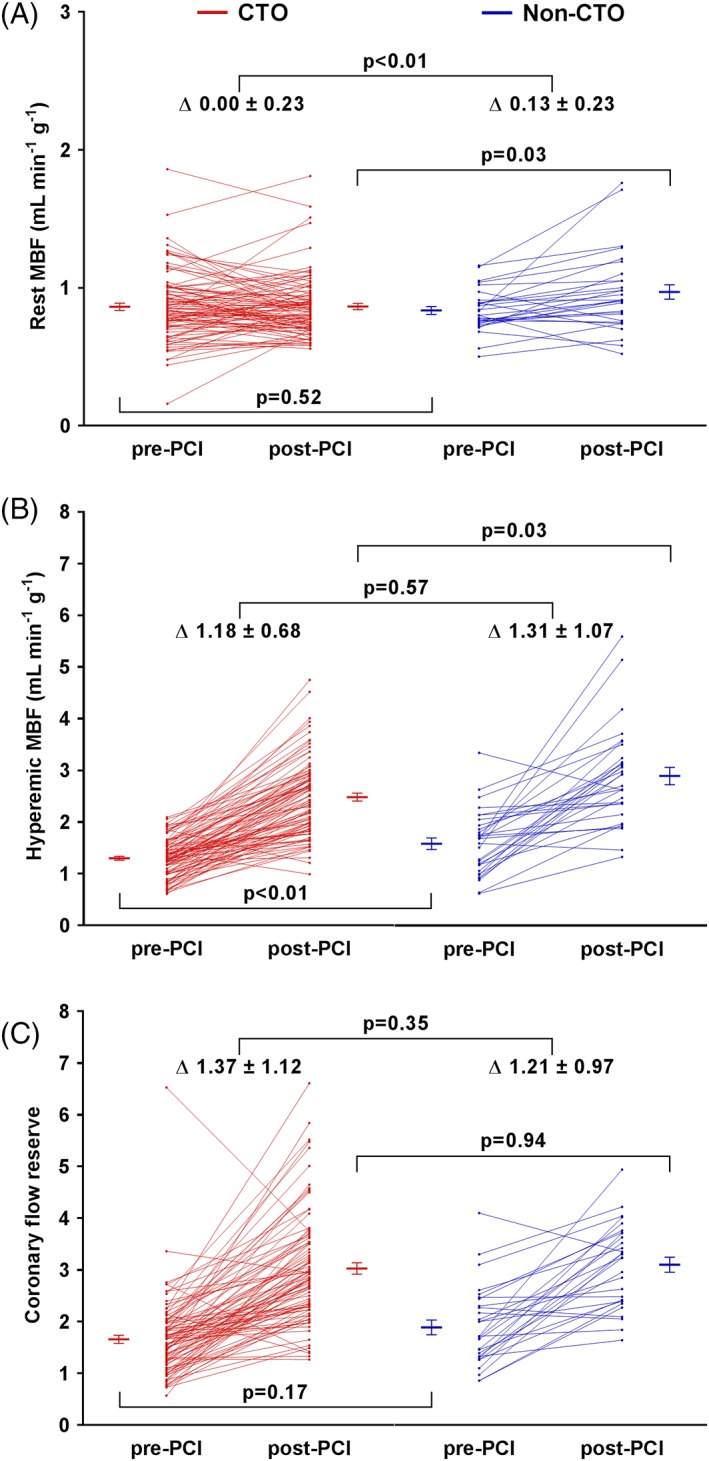

3.5. Effects of CTO PCI versus non‐CTO PCI on quantitative MBF

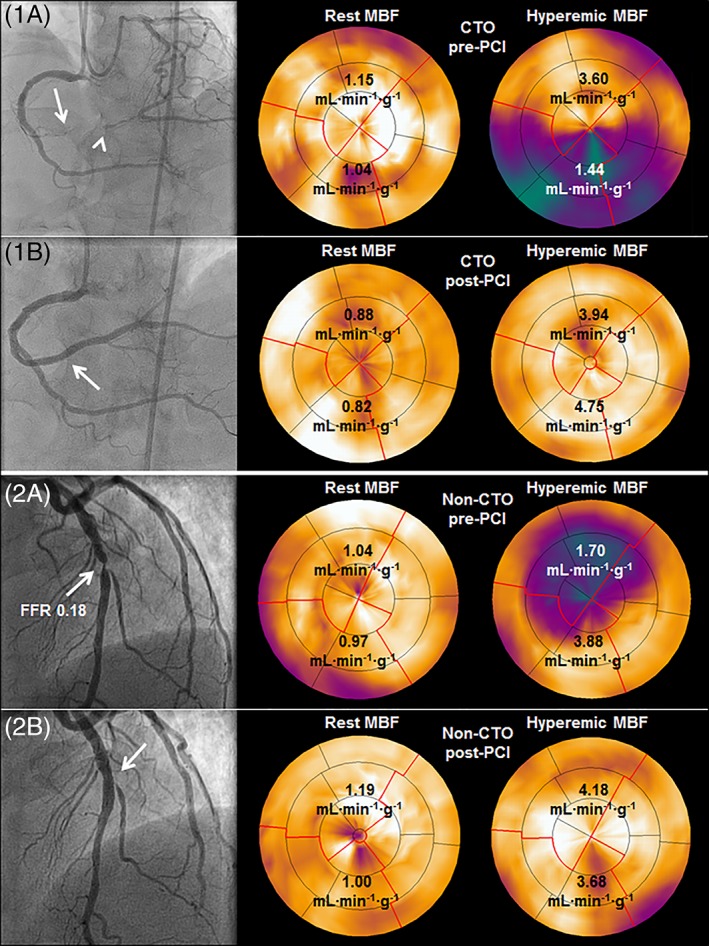

Patient examples of recovery of MBF after CTO PCI as well as non‐CTO PCI are demonstrated in Figure 1. Baseline rest MBF in the myocardial area subtended by a CTO and by a non‐CTO lesion was similar (P = 0.52) and increased after PCI in the non‐CTO group only (P < 0.01) to higher levels compared with the CTO group at follow‐up (P = 0.03) (displayed in Figure 2 and Table 3). Baseline hyperemic MBF was lower in patients with a CTO compared with patients with a non‐CTO lesion (P < 0.01). The increase in hyperemic MBF was significant and equivalent after both CTO PCI and non‐CTO PCI (P = 0.57). However, higher hyperemic MBF values were maintained in the non‐CTO group after PCI (P = 0.03). In the vascular territory of CTOs and non‐CTO lesions, CFR values were comparable at baseline (P = 0.17), and improved equally in both groups (P = 0.35) yielding comparable CFR levels after PCI (P = 0.94). As mentioned earlier, the extents of vessel disease and subsequent vessel PCI were similar between groups and regional PET perfusion results were not different between patients with one, two and three vessel disease (all comparisons P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

MBF restoration after percutaneous revascularization of a CTO and a non‐CTO lesion. (1A) MBF during hyperemia was severely reduced in the myocardial area distal of a CTO in the RCA (arrow: proximal cap, arrowhead: Distal cap) despite collateral supply by septal collaterals and a very well‐developed epicardial collateral arising from the LCx. (1B) successful percutaneous revascularization of the CTO (arrow) resulted in restoration of hyperemic MBF. (2A) a severe non‐CTO lesion in the LAD with an FFR of 0.18 (arrow) induced severely decreased hyperemic MBF, which recovered after successful PCI (2B, arrow). Abbreviations: CTO, chronic coronary total occlusion; FFR, fractional flow reserve; LCx, left circumflex coronary artery; MBF, myocardial blood flow; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 2.

Per patient quantitative MBF during rest (A) and hyperemia (B) and CFR (C) are displayed for patients with a CTO and patients with a non‐CTO lesion before PCI, after PCI and the change in between. Error bars display mean ± SEM. Corresponding values are mean ± SD. CFR, coronary flow reserve. Other abbreviations as in Figure 1 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

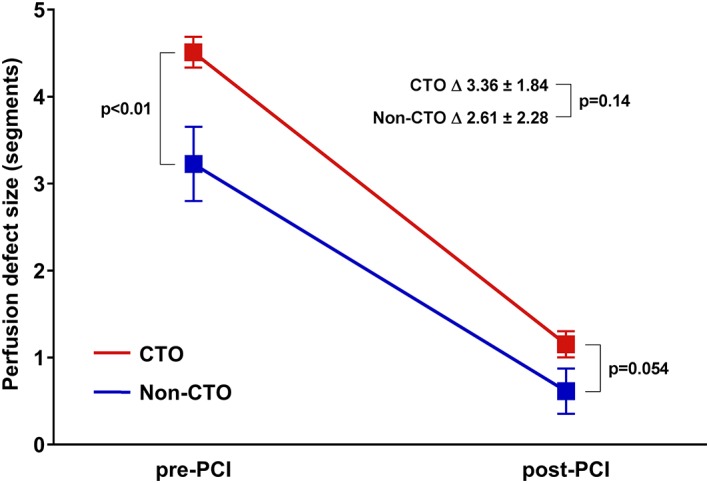

3.6. Effects of CTO PCI versus non‐CTO PCI on perfusion defect size

The perfusion defect size, as measured in myocardial segments, comprised at baseline more myocardium in patients with a CTO compared with patients with a non‐CTO lesion (P < 0.01) (Figure 3). The effect of PCI on the perfusion defect size was similar in both groups (P = 0.14), resulting in insignificantly different and small residual perfusion defect sizes (P = 0.054).

Figure 3.

Perfusion defect size in myocardial segments before and after PCI of a CTO and a non‐CTO lesion. At baseline, the average perfusion defect size was significantly more comprehensive in the CTO group compared with the non‐CTO group. Percutaneous revascularization led to significant improvements with small residual perfusion defects in both groups as a result. Error bars display mean ± SEM. Corresponding values are mean ± SD. Abbreviations: CTO, chronic coronary total occlusion; FFR, fractional flow reserve; LCx, left circumflex coronary artery; MBF, myocardial blood flow; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4. DISCUSSION

This study is the first head‐to‐head comparison between the effects of percutaneous revascularization of CTOs and hemodynamically significant non‐CTO lesions on quantitative MBF and perfusion defect size. The main findings are as follows: (1) CTOs subtend a more extensive perfusion defect size with lower MBF during hyperemia compared with non‐CTO lesions; (2) CTO PCI and non‐CTO PCI yield significant and comparable improvements in hyperemic MBF, CFR, and perfusion defect size; (3) after both CTO PCI and non‐CTO PCI satisfying results in quantitative MBF and perfusion defect size are achieved.

4.1. Patient selection and characteristics

Patients with a CTO had a more severe cardiac risk profile compared with patients with non‐CTO lesions. 25% of patients with a CTO suffered from prior MI even though only patients with preserved LVEF were included in this analysis. The patient groups were selected from prior studies with different in‐ and exclusion criteria, which can (partially) explain these differences. However, patients with a CTO are known to have more extensive CAD and comorbidity than patients with CAD without a CTO.1 All PET perfusion results were corrected for age and gender when comparing between groups, and by selecting patients with a preserved LVEF only, the extent and influence of previous MI was attempted to be minimized.

4.2. The influence of a CTO versus a non‐CTO lesion on myocardial perfusion

To achieve a genuine comparison between CTOs and non‐CTO lesions, only FFR defined hemodynamically significant lesions were included in the non‐CTO group. Thresholds for significant CAD with [15O]H2O PET (hyperemic MBF: 2.3 mL·min−1·g−1, and CFR: 2.5) have been well established previously after validation with FFR, and in this study, in both groups baseline hyperemic MBF and CFR were indicative for significant CAD.20 At baseline, rest MBF and CFR values were comparable in patients with a CTO and patients with a non‐CTO lesion. On the contrary, baseline hyperemic MBF was lower and the associated perfusion defect size was more extensive in the CTO group. These findings may be expected given the absence of antegrade flow and the complete dependence on collateral supply in CTOs. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that well‐developed collaterals cannot preserve adequate blood supply to a CTO territory during increased demand.9, 10, 11 In addition, prior MI, although sometimes unrecognized in patients with a CTO, and microvascular dysfunction, are regularly present in the myocardial area supplied by a CTO.21, 22 Additional analyses in this study showed comparable PET perfusion results between CTO patients with and without documented prior MI in the myocardium subtended by the CTO. However, the combined effect of a higher prevalence of CAD risk factors, prior (unrecognized) MI, and prior revascularization in patients with a CTO could hypothetically have led to relatively more microvascular disease in the CTO area, (partially) causing diminished hyperemic MBF and (non‐significantly) lower CFR in these patients.23 Using [15O]H2O PET perfusion, it has previously been shown that MBF during hyperemia is inversely related to the extent of surrounding scar tissue in patients with a CTO.13

4.3. Effects of CTO PCI versus non‐CTO PCI on myocardial perfusion

A significant increase in rest MBF was seen after non‐CTO PCI, whilst no change occurred after CTO PCI. Hypothetically this increase after non‐CTO PCI can be the recovery of chronic hypoperfusion in former hibernating myocardium. Overall viability in the target vessel territory was preserved in all individuals. However, 25% of patients in the CTO group had suffered previously from MI in the vascular territory of the CTO, and this might have resulted in relatively less hibernating myocardium present in these patients at baseline. Improvement in hyperemic MBF and CFR after CTO PCI and non‐CTO PCI was comparable, leading to normalization of the above‐mentioned indices in both patient groups.20 Still, relatively higher MBF levels during hyperemia were observed after PCI in the non‐CTO group. With lower levels at baseline and in the presence of potentially more microvascular dysfunction (vide supra), the demonstrated hyperemic MBF levels achieved after CTO PCI, which were slightly lower as compared with remote areas, probably represent the optimal results for these patients. Because the majority of the CTO lesions were located in the RCA (70%) and most non‐CTO lesions in the LAD (68%), the higher hyperemic MBF levels in patients with non‐CTO lesions could theoretically be caused by the disparity of target vessels between groups. In an additional analysis in the total cohort of patients comparing target lesions in the RCA with target lesions in the LAD, however, comparable hyperemic MBF levels were found at baseline (P = 0.52), at follow‐up (P = 0.70), and in change of hyperemic MBF (P = 0.98). Another possible explanation for relatively lower (although already normalized) hyperemic MBF levels after CTO PCI would be the procedure leading to suboptimal results. Because the vessel is totally occluded, a CTO can be crossed through the luminal plaque or around the lesion through the subintimal space by means of a DR technique. Higher rates of restenosis and repeat target vessel revascularization after the usage of wire‐based DR techniques have been reported previously.24, 25 After the introduction of more controlled device‐based DR techniques, however, wire‐based DR techniques are increasingly being used as a bailout strategy when other strategies in CTO PCI fail. This development has led to acceptable repeat revascularization rates after usage of DR techniques comparable with intraplaque crossing techniques.26 In this study in the CTO group, intraplaque crossing and stenting resulted in relatively higher hyperemic MBF after PCI compared with a successful DR technique. The (inappropriate) usage of a DR technique can lead to long dissection planes with a potential for side branch loss, longer stent lengths and stent under‐sizing due to hematoma formation, and in this study these unfavorable features could hypothetically have led to less recovery of hyperemic MBF. However, the recently published results of the randomized IMPACTOR‐CTO trial showed that only a marginal nonsignificant reduction in ischemic burden could be realized with optimal medical therapy alone (without successful crossing and stenting) in patients with a CTO.27 Although hyperemic MBF after the usage of DR techniques was relatively lower in this study, it should be noted that these techniques led to successful CTO crossing and subsequent reduction in ischemic burden in 48% of the patients, and they can be considered as essential additives in CTO PCI.5 The potential differences in restoration of myocardial perfusion after intraplaque crossing and DR techniques in CTO PCI should be further investigated in more detail in a larger patient cohort. Reductions in perfusion defect size were on average 3.36 and 2.61 segments after CTO PCI and non‐CTO PCI, representing 21 and 16% of the left ventricle myocardium respectively, and can be considered as clinically relevant.28 After PCI, residual perfusion defect sizes in both groups of patients were rather small (<10% of the left ventricle), and in case of refractory complaints, further optimization of medical therapy would be appropriate in these patients.8

4.4. CTO PCI and non‐CTO PCI: Different procedures with comparable effects

In stable patients with equivalent myocardial ischemia and symptom severity, CTO PCI is applied more conservatively than PCI of a (hemodynamically significant) non‐CTO lesion.14 This study shows that both treatments lead to similar and satisfying improvements in terms of quantitative MBF and perfusion defect size if patients are appropriately selected based on ischemia prior to revascularization. Approximately half of the CTOs had morphologic characteristics of high anatomic complexity (J‐CTO score of ≥2). With all incorporated techniques to revascularize CTO lesions, high anatomic complexity of a CTO becomes less of a boundary to achieve satisfying results, which is illustrated by the recovery of perfusion after CTO PCI in this study. This study adds to the scarce body of evidence that among patients with ischemia as indication for revascularization, CTO PCI should be applied in a similar way as non‐CTO PCI. With contemporary high success and acceptable complication rates in CTO PCI, it is a treatment strategy that should readily be considered albeit with appropriate patient selection.5, 29

4.5. Limitations

Only patients with a LVEF ≥50% were selected and present results cannot be extrapolated to patients with lower LVEF values. Patients in the non‐CTO group were referred to the cathlab irrespectively of PET perfusion results according to the study protocol. In patients with a CTO, non‐invasive ischemia detection was used for appropriate patient selection for revascularization. This could have led to the selection of CTOs with relatively more ischemic burden. Regional PET perfusion results were comparable between LAD and RCA lesions and in patients with one, two, or three vessel disease. It cannot be excluded, however, that more detailed inequalities in lesion location and extent of disease have diluted the comparison between the effects of CTO PCI and non‐CTO PCI. Cardiac biomarkers were not obtained systematically and the influence of potentially unrecognized periprocedural myocardial injuries in the CTO group (especially after retrograde approaches) on the follow‐up PET perfusion results is unclear.30 With lack of angiographic control at time of follow‐up PET imaging, it cannot be excluded that recurrent luminal narrowing has influenced the results in a negative manner in some patients. The mean time interval between PCI and follow‐up PET was 110 days in the CTO group and 23 days in the non‐CTO group due to different imaging protocols in the two patient cohorts. With absence of restenosis, a gradual increase of perfusion after angioplasty at 1 week and 3 months follow‐up has been reported previously.31 If the duration between PCI and follow‐up PET imaging in the non‐CTO group would have been longer, this could potentially have led to more advantageous results. The recently published results of the randomized sham‐controlled ORBITA trial showed comparable improvements in patient health status after PCI and optimal medical therapy despite the significant improvements in invasive and non‐invasive perfusion indices after PCI.32 In this study, patient symptoms were not systematically obtained after PCI during follow‐up, and therefore lacks the exploration of a possible correlation between improvement of (hyperemic) MBF and patient symptoms or quality of life.

5. CONCLUSION

In general, hyperemic myocardial perfusion is slightly more hampered in patients with a CTO before and after PCI. Percutaneous revascularization of CTOs, however, improves hyperemic MBF, CFR, and the perfusion defect size similar to PCI of hemodynamically significant non‐CTO lesions, leading to satisfying results.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Nothing to report.

Schumacher SP, Driessen RS, Stuijfzand WJ, et al. Recovery of myocardial perfusion after percutaneous coronary intervention of chronic total occlusions is comparable to hemodynamically significant non‐occlusive lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93:1059–1066. 10.1002/ccd.27945

REFERENCES

- 1. Fefer P, Knudtson ML, Cheema AN, et al. Current perspectives on coronary chronic total occlusions: The Canadian multicenter chronic Total occlusions registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(11):991–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brilakis ES, Banerjee S, Karmpaliotis D, et al. Procedural outcomes of chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(2):245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Joyal D, Afilalo J, Rinfret S. Effectiveness of recanalization of chronic total occlusions: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Am Heart J. 2010;160(1):179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brilakis ES, Grantham JA, Rinfret S, et al. A percutaneous treatment algorithm for crossing coronary chronic total occlusions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(4):367–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maeremans J, Walsh S, Knaapen P, et al. The hybrid algorithm for treating chronic Total occlusions in Europe: The RECHARGE registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(18):1958–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Galassi AR, Werner GS, Tomasello SD, et al. Prognostic value of exercise myocardial scintigraphy in patients with coronary chronic total occlusions. J Interv Cardiol. 2010;23(2):139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Cohen I, Berman DS. Comparison of the short‐term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003;107(23):2900–2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the task force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio‐Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35(37):2541–2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stuijfzand WJ, Driessen RS, Raijmakers PG, et al. Prevalence of ischaemia in patients with a chronic total occlusion and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;18(9):1025–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sachdeva R, Agrawal M, Flynn SE, Werner GS, Uretsky BF. The myocardium supplied by a chronic total occlusion is a persistently ischemic zone. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83(1):9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aboul‐Enein F, Kar S, Hayes SW, et al. Influence of angiographic collateral circulation on myocardial perfusion in patients with chronic total occlusion of a single coronary artery and no prior myocardial infarction. J Nucl Med. 2004;45(6):950–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Safley DM, Koshy S, Grantham JA, et al. Changes in myocardial ischemic burden following percutaneous coronary intervention of chronic total occlusions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;78(3):337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stuijfzand WJ, Biesbroek PS, Raijmakers PG, et al. Effects of successful percutaneous coronary intervention of chronic Total occlusions on myocardial perfusion and left ventricular function. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:345–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Strauss BH, Shuvy M, Wijeysundera HC. Revascularization of chronic total occlusions: time to reconsider? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(12):1281–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Danad I, Raijmakers PG, Driessen RS, et al. Comparison of coronary CT angiography, SPECT, PET, and hybrid imaging for diagnosis of ischemic heart disease determined by fractional flow reserve. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1100–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stone GW, Kandzari DE, Mehran R, et al. Percutaneous recanalization of chronically occluded coronary arteries: a consensus document: part I. Circulation. 2005;112(15):2364–2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morino Y, Abe M, Morimoto T, et al. Predicting successful guidewire crossing through chronic total occlusion of native coronary lesions within 30 minutes: the J‐CTO (multicenter CTO registry in Japan) score as a difficulty grading and time assessment tool. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(2):213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular endpoint events in clinical trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical data standards (writing committee to develop cardiovascular endpoints data standards). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(4):403–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, et al. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the cardiac imaging Committee of the Council on clinical cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105(4):539–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Danad I, Uusitalo V, Kero T, et al. Quantitative assessment of myocardial perfusion in the detection of significant coronary artery disease: cutoff values and diagnostic accuracy of quantitative [(15)O]H2O PET imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(14):1464–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Werner GS, Ferrari M, Richartz BM, Gastmann O, Figulla HR. Microvascular dysfunction in chronic total coronary occlusions. Circulation. 2001;104(10):1129–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi JH, Chang SA, Choi JO, et al. Frequency of myocardial infarction and its relationship to angiographic collateral flow in territories supplied by chronically occluded coronary arteries. Circulation. 2013;127(6):703–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Camici PG, d'Amati G, Rimoldi O. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: mechanisms and functional assessment. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(1):48–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Valenti R, Vergara R, Migliorini A, et al. Predictors of reocclusion after successful drug‐eluting stent‐supported percutaneous coronary intervention of chronic total occlusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(5):545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Azzalini L, Dautov R, Brilakis ES, et al. Procedural and longer‐term outcomes of wire‐ versus device‐based antegrade dissection and re‐entry techniques for the percutaneous revascularization of coronary chronic total occlusions. Int J Cardiol. 2017;231:78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karatasakis A, Danek BA, Karacsonyi J, et al. Mid‐term outcomes of chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention with subadventitial vs. intraplaque crossing: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2018;253:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Obedinskiy AA, Kretov EI, Boukhris M, et al. The IMPACTOR‐CTO trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(13):1309–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the clinical outcomes utilizing revascularization and aggressive drug evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008;117(10):1283–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Galassi AR, Brilakis ES, Boukhris M, et al. Appropriateness of percutaneous revascularization of coronary chronic total occlusions: an overview. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(35):2692–2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dautov R, Ybarra LF, Nguyen CM, Gibrat C, Joyal D, Rinfret S. Incidence, predictors and longer‐term impact of troponin elevation following hybrid chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018. 10.1002/ccd.27545. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Uren NG, Crake T, Lefroy DC, de Silva R, Davies GJ, Maseri A. Delayed recovery of coronary resistive vessel function after coronary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21(3):612–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Al‐Lamee R, Thompson D, Dehbi HM, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): a double‐blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10115):31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]