Abstract

Relationships that traverse sociodemographic categories may improve community attitudes toward marginalized groups and potentially protect members of those groups from stigma and discrimination. The present study evaluated whether internalized HIV stigma and perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings differ based on individual- and neighborhood-level characteristics of women living with HIV (WLHIV). We also sought to extend previous conceptual and empirical work to explore whether perceived HIV-related discrimination mediated the association between neighborhood racial diversity and internalized HIV stigma. A total of 1256 WLHIV in the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) attending 10 sites in metropolitan areas across the United States completed measures of internalized HIV stigma and perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings. Participants also provided residential information that was geocoded into Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) codes and linked with census-tract level indicators. In cross-sectional analyses, greater neighborhood racial diversity was associated with less internalized HIV stigma and less perceived HIV-related discrimination regardless of individual race. Neighborhood median income was positively associated with internalized HIV stigma and perceived discrimination, while individual income was negatively associated with perceptions of stigma and discrimination. In an exploratory mediation analysis, neighborhood racial diversity had a significant indirect effect on internalized HIV stigma through perceived HIV-related discrimination. An indirect effect between neighborhood income and internalized stigma was not supported. These findings suggest that greater neighborhood racial diversity may lessen HIV stigma processes at the individual level and that HIV stigma-reduction interventions may be most needed in communities that lack racial diversity.

Keywords: geocoding, racial diversity, HIV, internalized stigma, discrimination, women

Introduction

Women—particularly women of color—face a high burden of HIV-related stigma in North America. As of 2014, women represented 23% of all people living with HIV (PLHIV) in the United States; and of the total number of women living with HIV (WLHIV) in the United States, over 80% were women of color.1 Both women and black and African American individuals report more HIV-related stigma relative to other groups.2,3

Quantitative analyses of HIV-related stigma among PLHIV in the United States and Canada examined the interaction between gender and race and found that women reported greater total stigma scores and stigma dimension scores (including perceived discrimination and internalized stigma) compared to men; and non-white women reported greater HIV-related stigma relative to white WLHIV.4,5 Qualitative investigations exploring women's experiences of stigma highlight the intersection of gender and race that result in harsh judgments toward WLHIV in their communities.6–8 Lekas et al. found that women felt more protected from experiences of stigma in their own racial communities, compared to in society at large where they felt more vulnerable to stigma.6

Research linking neighborhood characteristics to HIV risk behaviors and health outcomes broadens our understanding of the ways physical and social environments shape HIV-related health.9 This field of empirical research increased attention to social and structural determinants of health, enhanced understanding of HIV risk environments, and was enabled by access to geocoding methods to link residential addresses with neighborhood-level data.

From such research we learned that unsuppressed HIV viral load is more common among PLHIV in the most socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods.10 When controlling for individual demographic characteristics, including age, gender, race, and income, such evidence emerges: PLHIV residing in neighborhoods with a higher proportion of poverty had 1.50 greater odds of having a CD4 cell count characteristic of an AIDS diagnosis (<200 cells/μL), PLHIV in neighborhoods with higher prevalence of unemployment were almost 50% less likely to have a current antiretroviral prescription, and PLHIV were more likely to report depressive symptoms if they resided in racially segregated neighborhoods.11 Moreover, a measure of neighborhood disorder, an indicator of economic disadvantage, was associated with poorer antiretroviral treatment (ART) adherence.12 Thus, neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and racial segregation are linked with poor health outcomes.

A separate literature has documented the harmful effects of HIV-related stigma on health.13,14 HIV stigma is a social process through which people living with or perceived to be living with HIV are socially devalued and excluded for the purpose of maintaining power and inequality in a broader social context.15,16 Stigma manifests as acts of discrimination in which PLHIV face overt and subtle differences in the way they are treated. Specifically in health care settings, which can represent a key source of support in one's community, PLHIV have reported receiving poorer quality of care, being blamed for their illness, or being denied care.17 The socialization of stigma also presents as internalized HIV stigma whereby some PLHIV accept and apply negative attitudes and feelings about PLHIV in the community to themselves.18

Increasingly, research has elucidated how these stigma mechanisms work together to affect health outcomes. Specifically, experiences of discrimination increase internalized HIV stigma, which has downstream negative effects on health outcomes (e.g., depressive symptoms, poorer ART adherence, and lower HIV care visit adherence).19–22 Tying together this literature on HIV-related stigma and health with the literature on neighborhood characteristics and health, we pose the question of whether neighborhood characteristics are associated with HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

In their Stigma and HIV Disparities Model, Earnshaw et al. explored residential segregation as a social determinant of stigma experienced at the individual level.23 However, little research has focused on neighborhood-level variables such as neighborhood socioeconomic status and racial composition in association with experiences of HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

Several studies have examined neighborhood racial composition and perceptions of racial discrimination. For instance, Hunt et al. found that African American women residing in neighborhoods with a higher proportion of black residents perceived less daily and lifetime racial discrimination.24 One explanation for their findings was based on the “group density hypothesis” whereby racial minorities in communities with others who predominantly identify with their own racial group have fewer opportunities to be discriminated against by other racial groups.25,26 Meanwhile, Eric Oliver and Wong found that people living in more racially diverse neighborhoods in the United States held fewer negative perceptions of people in other racial groups.27 Their findings may align with the tenets of contact theory, which postulates that more frequent interactions with people from other groups are associated with more favorable attitudes toward people belonging to those other groups.28–31 Contact theory has typically been applied to understanding the role of majority groups' stigmatizing attitudes toward racial and other minorities. Intergroup contact may reduce prejudice by decreasing anxiety related to intergroup interactions through exposure, increasing knowledge to unlearn prejudiced attitudes, and increasing empathy for others.29

Other research suggests that intergroup contact reduces perceived discrimination among those who are in the minority groups and more likely to be stigmatized.24,32 People residing in more diverse communities may experience less discrimination and, therefore, perceive less discrimination due to the reduction of stereotypes, prejudiced attitudes, and discrimination toward different groups by potential stigmatizers. In contrast, people in less segregated communities may be less attuned to separate group identities in daily life and, therefore, less likely to interpret others' attitudes as discrimination.23 Contact theory can be extended to attitudes toward identities other than race, such that people in more diverse racial communities report more favorable attitudes regarding other minority group characteristics such as sexual orientation or physical disability.28,30

In the present study, we examined how individual race and neighborhood racial composition relate to internalized HIV stigma and perceived HIV-related discrimination among WLHIV in the United States. Based on the prior theoretical and empirical work discussed in this study, we hypothesized that women of color would report more internalized HIV stigma and perceive more HIV-related discrimination in health care settings. With regard to neighborhood racial composition, we hypothesized that living in a more racially diverse community would be associated with lower levels of internalized HIV stigma and perceptions of HIV-related discrimination. To account for potential group density effects, we also examined the relationship between participants' race concordance with their neighborhood to determine whether living in a community with high proportion of residents in one's own race was protective for WLHIV against internalized HIV stigma and perceived HIV-related discrimination. Further, given the evidence that experiences of discrimination reinforce internalized HIV stigma,14,19,20,22,33 we expected that lack of neighborhood racial diversity would work through the pathway of perceived HIV-related discrimination to lead to higher levels of internalized HIV stigma.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Participants were WLHIV enrolled in the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), a national cohort study of women living with or at risk for HIV infection in the United Sates.34 Women were included from nine WIHS sites located in Bronx, NY; Brooklyn, NY; Washington DC; San Francisco, CA; Chicago, IL; Chapel Hill, NC; Atlanta, GA; Miami, FL; and Birmingham, AL/Jackson, MS. Participants were included in the present analysis if they attended their WIHS visit between April and September 2015, completed measures of internalized HIV stigma and HIV-related discrimination in health care settings, and provided their residential address.

Participants' residential addresses were each matched with a Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) code using ArcGIS™35 FIPS codes identifying that geographical locations were then linked with census data from the 2014 5-year American Community Survey (ACS).36 Census-tract level data utilized in this analysis included race proportions by the seven racial categories assessed in the US Census, median income of the census tract, and proportion of residents with a high school education or more.

Measures

Demographic and health information

Women reported their age, race, ethnicity, level of education, time on ART medication, and their approximate annual household income on the following scale: 1: ≤$6000; 2: $6001–12,000; 3: $12,001–18,000; 4: $18,001–24,000; 5: $24,001–30,000; 6: $30,001–36,000; 7: $36,001–75,000; and 8: >75,000.

Internalized HIV stigma

The 7-item negative self-image subscale of the HIV Stigma Scale37,38 was used to assess internalized HIV stigma. Participants responded to items (e.g., “Having HIV/AIDS makes me feel that I'm a bad person.”) on a scale from 1: Strongly Disagree to 4: Strongly Agree. The mean score of the 7 items was calculated for each participant.

Perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings

In the WIHS study, one item was used to assess perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings: “I feel discriminated against in healthcare settings because of my HIV status.” Participants responded on a scale from 1: Strongly Disagree to 4: Strongly Agree. This item was adapted from the PLHIV Stigma Index39 and the Experiences of Discrimination Scale,40 both of which have been used to predict health outcomes using global perceptions of discrimination in different settings. Turan et al. found that this one item predicts internalized HIV stigma, as well as HIV-related health outcomes like adherence.20

Neighborhood characteristics

Census tracts were dummy coded before analysis. Characteristics of participants' neighborhoods (census tracts) included in the present analysis were the median household income, proportion of residents who completed high school or more, and proportions of different races within neighborhoods based on estimates from the ACS. The median household income variable was transformed by dividing by 1000 for interpretability of the unstandardized beta coefficients.

Using race proportions within census tracts, a racial diversity index (RDI)41,42 was calculated for each participant's census tract. The US Census categorizes household race in the following groups: African American, European American, Asian American, Hawaiian American, Native American, Other, and two or more races. Note that Hispanic American was categorized separately as ethnicity and not included in the racial proportion of census tracts. For this analysis, women who identified their ethnicity as Hispanic were categorized by their identified race. The following formula was used to calculate the racial diversity within census tracts:

|

where p is the proportion of people belonging to each of the seven race categories. This equation yields an index ranging from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates a completely homogeneous neighborhood and 1 indicates a perfectly heterogeneous neighborhood.

A variable for participant race concordance with neighborhood was created by matching each participant's identified race with the race proportion for her neighborhood. For example, if a participant identified her race as African American, we created a variable for her representing the proportion of residents in her census tract who were African American.

Data analysis

Data were managed using SPSS version 23. Descriptive analyses were conducted to characterize the sample. A Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) approach was used. GEE accounts for variance clustering that occurs when individuals are nested within another variable. In this case, participants were nested in census tracts. An exchangeable correlation structure was used. The following covariates (used in previous research with this cohort) were included in all analyses: age, years on ART, annual household income, dichotomized education (0: did not complete high school, 1: high school diploma or more), and categorized race (0: white, 1: black/African American, 2: Other race). Race was categorized this way because two of the race categories (Asian/Pacific Islander and Native American) were not large enough to compare with the other groups.

The first models included covariates only to assess individual demographic characteristics in association with (1) internalized HIV stigma and (2) perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings. Next, neighborhood variables were added together to the model, including median household income, proportion of residents with high school education, and the calculated RDI variable. These analyses were repeated with participant race concordance with their neighborhood entered instead of RDI. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Finally, an exploratory mediation analysis was conducted to determine if perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings mediated the association between RDI and internalized HIV stigma. We conducted a second mediation model with neighborhood median income as the predictor instead of RDI. Mediation was assessed using SPSS PROCESS43 by examining the confidence interval (CI) of the indirect effect of RDI on internalized HIV stigma. Significant mediation is present when the 95% CI does not contain 0. Bootstrapping was used with 5000 re-samples, to assess effects without assuming normality of the sampling distribution.44 All covariates that were entered in the previous GEE models were entered in the mediation model, including controlling for clustering by census tract. Unstandardized beta coefficients are presented to promote interpretation based on the metrics used in the study.

Results

Description of individual and neighborhood variables

The analysis sample included 1256 WLHIV, described in Table 1. The average age of participants at their study visit was ∼49 years [standard deviation (SD): 9, range: 25–79], and women reported having been on ART medications for an average of 11 years (SD: 7, range: 0–23). A total of 14% identified their race as white; 75% identified as African American or black; <1% identified as Asian or Pacific Islander; <1% identified as Native American; and 10% identified their race as “Other.” A total of 15% identified their ethnicity as Hispanic.* Approximately 66% of participants completed a high school education or more. The majority of participants (37%) reported that their annual household income was in the range of $6001–12,000.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information of Sample of N = 1256 Women Living with HIV

| Individual variables | M ± SD, range or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48.9 ± 9.0, 25–79 |

| Years on ART | 10.6 ± 6.9, 0–23 |

| Race | |

| White | 181 (14) |

| Black/African American, non-Hispanic | 936 (75) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 7 (<1) |

| Native American | 10 (<1) |

| Other | 121 (10) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 189 (15) |

| Education | |

| <High school diploma | 428 (34) |

| >High school diploma | 828 (66) |

| Annual household income | |

| <$6000 | 182 (14) |

| $6001–12,000 | 465 (37) |

| $12,001–18,000 | 176 (14) |

| $18,001–24,000 | 116 (9) |

| $24,001–30,000 | 68 (5) |

| $30,001–36,000 | 66 (5) |

| $36,001–75,000 | 96 (8) |

| >$75,000 | 44 (4) |

| WIHS study site | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Bronx, NY | 166 (13) |

| Brooklyn, NY | 192 (15) |

| Washington DC | 118 (9) |

| San Francisco, CA | 166 (13) |

| Chicago, IL | 161 (13) |

| Chapel Hill, NC | 125 (10) |

| Atlanta, GA | 135 (11) |

| Miami, FL | 61 (5) |

| Birmingham, AL/Jackson, MS | 132 (10) |

| Stigma variables | M ± SD, range |

|---|---|

| Internalized HIV stigma | 1.8 ± 0.7, 1–4 |

| Perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings | 1.7 ± 0.8, 1–4 |

| Neighborhood variables | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Median annual household income | $37,000 ($27,000–$53,000) |

| Proportion with high school education | 84.1 (71.7–93.4) |

| RDI | 0.5 (0.2–0.6) |

| Proportion race concordance | 55.9 (23.2–84.0) |

ART, antiretroviral treatment; IQR, interquartile range; RDI, racial diversity index; SD, standard deviation; WIHS, Women's Interagency HIV Study.

The median household income of participants' neighborhoods (census tracts) was ∼$37,000 [Interquartile range (IQR): $27,000–$53,000]. The median proportion of residents with at least a high school education was ∼84% (IQR: 71–93). The median RDI of women's neighborhoods was 0.5 (IQR: 0.2–0.6) suggesting that participants' neighborhoods were slightly more racially homogeneous than heterogeneous and no woman lived in a perfectly racially heterogeneous neighborhood. Participants' median race concordance with their neighborhood was ∼56% (IQR: 23–84).

GEE analyses of individual demographic variables

Internalized HIV stigma

Results from the individual-level variables-only model are presented in Table 2 and show that all covariates were significantly associated with internalized HIV stigma except for education level [B (standard error, SE) = −0.068 (0.042), 95% CI (−0.149 to 0.014)], black/African American race [B (SE) = −0.007 (0.052), 95% CI (−0.109 to 0.095)], and Other race [B (SE) = −0.037 (0.070), 95% CI (−0.174 to 0.100)]. Lower age was associated with an increase in internalized HIV stigma [B (SE) = −0.009 (0.002), 95% CI (−0.014 to −0.005)], as was fewer years on ART [B (SE) = −0.013 (0.003), 95% CI (−0.019 to −0.007)]. Lower household income was associated with greater internalized HIV stigma [B (SE) = −0.030 (0.009), 95% CI (−0.048 to −0.011)].

Table 2.

Cross-Sectional Relationships Between Demographic Variables and Internalized HIV Stigma and Perceived HIV-Related Discrimination in Health Care Settings Among Women Living with HIV (N = 1256)

| Variables | Outcome: internalized HIV stigmaa | Outcome: perceived HIV-related discrimination in a health care settingb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | 95% CI | B | SE | p | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 2.541 | 0.124 | <0.001 | 2.397 to 2.785 | 1.951 | 0.155 | <0.001 | 1.648 to 2.254 |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age | −0.009 | 0.002 | <0.001 | −0.014 to −0.005 | −0.004 | 0.003 | 0.173 | −0.009 to 0.002 |

| Years on ART | −0.013 | 0.003 | <0.001 | −0.019 to −0.007 | −0.004 | 0.004 | 0.247 | −0.012 to 0.003 |

| >High school education | −0.068 | 0.042 | 0.104 | −0.149 to 0.014 | −0.023 | 0.050 | 0.650 | −0.120 to 0.075 |

| Household income | −0.030 | 0.009 | 0.001 | −0.048 to −0.011 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.925 | −0.024 to 0.027 |

| Race (Ref: white) | ||||||||

| Black/African American | −0.007 | 0.052 | 0.889 | −0.109 to 0.095 | 0.036 | 0.069 | 0.597 | −0.099 to 0.172 |

| Other | −0.037 | 0.070 | 0.598 | −0.174 to 0.100 | −0.075 | 0.098 | 0.444 | −0.268 to 0.117 |

Internalized HIV stigma: 7 items, range 1–4, with higher scores indicating more internalized HIV stigma.

Perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings: 1 item, range 1–4, with higher scores indicating more perceived discrimination.

ART, antiretroviral treatment; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; SE, standard error.

Perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings

When the individual-level variables-only model was repeated with perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings as the outcome (Table 2), it was not associated with individuals' age [B (SE) = −0.004 (0.003), 95% CI (−0.009 to 0.002)], years on ART [B (SE) = −0.004 (0.004), 95% CI (−0.012 to 0.003)], education [B (SE) = −0.023 (0.050), 95% CI (−0.120 to 0.075)], or household income [B (SE) = 0.001 (0.013), 95% CI (−0.024 to 0.027)], black/African American race [B (SE) = 0.036 (0.069), 95% CI (−0.099 to 0.172)], or Other race [B (SE) = −0.075 (0.098), 95% CI (−0.268, to 0.117)].

GEE analysis of neighborhood variables: racial diversity index

Internalized HIV stigma

Results from the GEE model with RDI as a predictor of internalized HIV stigma, controlling for individuals' age, time on ART, household income, dichotomized education, categorized race, neighborhood median household income, and proportion neighborhood with high school education, are presented in Table 3. Results showed a significant negative association between RDI and internalized HIV stigma [B (SE) = −0.359 (0.095), 95% CI (−0.545 to −0.173)]. Neighborhood median household income was positively associated with internalized HIV stigma [B (SE) = 0.002 (0.001), 95% CI (0.000 to 0.003)]. In contrast, neighborhood education attainment was not associated with internalized HIV stigma [B (SE) = −0.001 (0.001), 95% CI (−0.003 to 0.001)].

Table 3.

Cross-Sectional Relationships Between Neighborhood Racial Diversity, Internalized HIV Stigma, and Perceived HIV-Related Discrimination in Health Care Settings Among Women Living with HIV (N = 1256)

| Variables | Outcome: internalized HIV stigmaa | Outcome: perceived HIV-related discrimination in a health care settingb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | 95% CI | B | SE | p | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 2.720 | 0.156 | <0.001 | 2.414 to 3.026 | 2.160 | 0.201 | <0.001 | 1.766 to 2.553 |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age (years) | −0.009 | 0.002 | <0.001 | −0.014 to −0.005 | −0.003 | 0.003 | 0.222 | −0.009 to 0.002 |

| Years on ART | −0.013 | 0.003 | <0.001 | −0.019 to −0.007 | −0.005 | 0.004 | 0.239 | −0.012 to 0.003 |

| >High school education | −0.082 | 0.041 | 0.047 | −0.163 to −0.001 | −0.041 | 0.050 | 0.411 | −0.139 to 0.057 |

| Household income | −0.035 | 0.010 | <0.001 | −0.054 to −0.016 | −0.005 | 0.014 | 0.716 | −0.031 to 0.022 |

| Race (Ref: white) | ||||||||

| Black/African American | −0.022 | 0.053 | 0.677 | −0.125 to 0.081 | 0.021 | 0.070 | 0.764 | −0.116 to 0.158 |

| Other | 0.000 | 0.070 | 0.998 | −0.137 to 0.138 | −0.041 | 0.098 | 0.679 | −0.233 to 0.152 |

| Neighborhood characteristics | ||||||||

| Proportion high school | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.367 | −0.003 to 0.001 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.270 | −0.004 to 0.001 |

| Education in neighborhood | ||||||||

| Median household income of neighborhood/1000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.027 | 0.000 to 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.000 to 0.004 |

| RDIc | −0.359 | 0.095 | <0.001 | −0.545 to −0.173 | −0.368 | 0.121 | 0.002 | −0.606 to −0.131 |

Internalized HIV stigma: 7 items, range 1–4, with higher scores indicating more internalized HIV stigma.

Perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings: 1 item, range 1–4, with higher scores indicating more perceived discrimination.

Calculated RDI: 0 = completely homogeneous neighborhood to 1 = completely heterogeneous neighborhood.

ART, antiretroviral treatment; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; RDI, Racial Diversity Index; SE, standard error.

Individual covariates remained significantly associated with internalized HIV stigma with similar coefficients in the model with RDI as in the individual-level variables-only model. Categorized race was not associated with internalized HIV stigma. Age, time on ART, and household income were again negatively associated with internalized HIV stigma. Individual level education attainment was negatively associated with internalized HIV stigma in this model, including neighborhood context.

Perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings

The same GEE model except with perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings as the outcome instead of internalized HIV stigma was examined, and results of this model are also shown in Table 3. RDI was negatively associated with perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings [B (SE) = −0.368 (0.121), 95% CI (−0.606 to −0.131)]. Median neighborhood household income was associated with greater perceived discrimination in health care settings [B (SE) = 0.002 (0.001), 95% CI (0.000 to 0.004)]. Neighborhood education level was not associated with perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings, nor was any of the individual-level covariates.

GEE analysis of neighborhood variables: participant race concordance

Internalized HIV stigma

To examine our alternative group density hypothesis, we repeated the analyses with the created participant race concordance with neighborhood variable as the predictor (Table 4). Participant race concordance with neighborhood was not associated with internalized HIV stigma [B (SE) <0.001 (0.001), 95% CI (−0.001 to 0.002)]. In this analysis, age, time on ART, and income were negatively associated with internalized HIV stigma similar to the individual-level variables-only model. Neighborhood median income was positively associated with internalized HIV stigma similar to the previous RDI model.

Table 4.

Cross-Sectional Relationships Between Participant Race Concordance with Neighborhood, Internalized HIV Stigma, and Perceived HIV-Related Discrimination in Health Care Settings Among Women Living with HIV (N = 1256)

| Variables | Outcome: internalized HIV stigmaa | Outcome: perceived HIV-related discrimination in a health care settingb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | 95% CI | B | SE | p | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 2.633 | 0.175 | <0.001 | 2.291 to 2.975 | 2.152 | 0.221 | <0.001 | 1.718 to 2.586 |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age | −0.010 | 0.002 | <0.001 | −0.014 to −0.005 | −0.004 | 0.003 | 0.145 | −0.010 to 0.001 |

| Years on ART | −0.014 | 0.003 | <0.001 | −0.020 to −0.008 | −0.005 | 0.004 | 0.188 | −0.013 to 0.003 |

| >High school education | −0.078 | 0.042 | 0.060 | −0.160 to 0.003 | −0.038 | 0.050 | 0.446 | −0.137 to 0.060 |

| Household income | −0.034 | 0.010 | 0.001 | −0.053 to −0.015 | −0.003 | 0.014 | 0.847 | −0.029 to 0.024 |

| Race (Ref: white) | ||||||||

| Black/African American | −0.003 | 0.053 | 0.952 | −0.107 to 0.101 | 0.043 | 0.070 | 0.545 | −0.095 to 0.181 |

| Other | −0.014 | 0.074 | 0.851 | −0.159 to 0.131 | −0.083 | 0.102 | 0.413 | −0.282 to 0.116 |

| Neighborhood characteristics | ||||||||

| Proportion of high school education in neighborhood | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.095 | −0.004 to 0.000 | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.054 | −0.006 to 0.000 |

| Median household income of neighborhood/1000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.000 to 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.050 | 0.000 to 0.004 |

| Participant race concordancec | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.608 | −0.001 to 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.614 | −0.002 to 0.001 |

Internalized HIV stigma: 7 items, range 1–4, with higher scores indicating more internalized HIV stigma.

Perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings: 1 item, range 1–4, with higher scores indicating more perceived discrimination.

Proportion of participants' identified race category in their neighborhood of residence.

ART, antiretroviral treatment; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; SE, standard error.

Perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings

Participant race concordance with neighborhood was also not associated with perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings as shown in Table 4 [B (SE) <0.001 (0.001), 95% CI (−0.002 to 0.001)]. However in this analysis, neighborhood median income was not significantly associated with perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings as in the previous model.

Mediation analysis

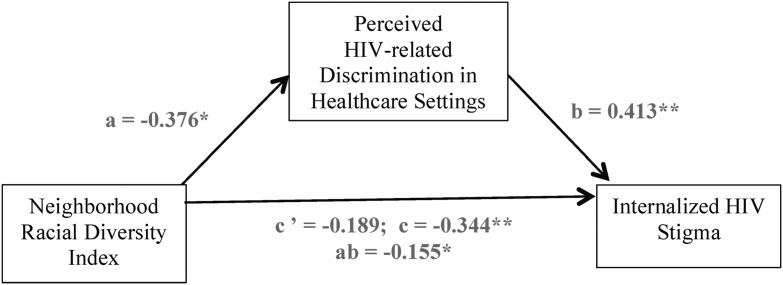

Finally, a mediation model was tested to explore whether perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings mediated the association between RDI and internalized HIV stigma. Model path coefficients are depicted in Fig. 1. The total effect of RDI on internalized HIV stigma [path c: B (SE) = −0.344 (0.095), 95% CI (−0.532 to −0.157)] decreased in magnitude when perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings was included in the model [path c’: B (SE) = −0.189 (0.082), 95% CI (−0.350 to −0.029)]. The bootstrapped CI of the indirect effect of RDI on internalized HIV stigma through perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings did not contain 0 [path ab: B (SE) = −0.155 (0.050), 95% CI: (−0.257 to −0.060)], indicating a mediated association between RDI and internalized HIV stigma through perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings.

FIG. 1.

Exploratory mediation model depicting the indirect effect of neighborhood racial diversity (RDI) on internalized HIV stigma through perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings, controlling for age, time on ART, categorized race, household income, dichotomized education, proportion with at least high school education in neighborhood, median household income of neighborhood, and census tract. c' is the direct effect; c is the total effect; ab is the indirect effect. **p < 0.001; *p < 0.01. ART, antiretroviral treatment; RDI, racial diversity index.

Mediation was not supported when the mediation model was repeated, replacing RDI with neighborhood median income as the predictor and entering RDI with the other covariates. There was not a significant indirect effect between neighborhood median income and internalized HIV stigma through perceived discrimination in health care settings [path ab: B (SE) = 0.001 (0.001), 95% CI: (−0.001 to 0.002)].

Discussion

In this cohort of WLHIV across the United States, greater neighborhood racial diversity was associated with less internalized HIV stigma and less perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings. In other words, living in a more racially diverse community appears to protect against perceived discrimination and internalized HIV stigma. Contrary to our first hypothesis, however, we did not find differences in perceived internalized HIV stigma or HIV-related discrimination in health care settings by individual race category regardless of neighborhood race and socioeconomic context. It could be that individual race does not necessarily drive perceptions of stigma, and greater context to racial disparities in HIV stigma is needed. In this study, we have described neighborhood characteristics as they relate to stigma perceptions among WLHIV, and intersectional and multilevel approaches to stigma measurement and intervention are needed.45

We also found that WLHIV reported greater internalized HIV stigma in the context of higher neighborhood household income, but lower individual household income. Relative socioeconomic deprivation may play a role in internalized HIV stigma based on these findings. Meanwhile, perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings was associated with higher neighborhood income regardless of individual income.

In addition, in exploratory analyses, perceived HIV-related discrimination mediated the association between neighborhood racial diversity and internalized HIV stigma. This finding adds context to an established connection between HIV-related discrimination and internalized stigma and suggests that women residing in communities that lack racial diversity are more likely to perceive HIV-related discrimination in health care settings, which in turn reinforces internalized HIV stigma. The health care setting can be an influential part of one's community, and perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings has a particularly negative impact on HIV-related health outcomes.20,22 It is also possible that this measure of HIV-related discrimination is a proxy for broader discrimination occurring in WLHIV communities.

Conceptual work supports the connection between structural factors, such as racial composition and socioeconomic status of one's neighborhood and individual perceptions of stigma and discrimination.23 Taken together with contact theory, our findings indicate that women living in more racially homogenous neighborhoods may expect and perceive more HIV-related discrimination. In contrast, women in more racially heterogeneous neighborhoods may perceive greater acceptance of alternative identities, including HIV status, and expect and perceive less discrimination that could lead to internalized HIV stigma. Future research could build upon the findings presented in this study to determine how neighborhood characteristics are associated with other forms of discrimination and relate to outcomes such as internalized stigma and HIV-related health.

We examined an alternative hypothesis that women's racial concordance with their neighborhood may protect against HIV-related stigma and discrimination, informed by research on group density.25,26 However, we did not find significant associations between women's racial concordance with their neighborhoods and internalized HIV stigma or perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings. In other words, residing in a neighborhood with others predominantly identifying as one's own race did not affect internalized HIV stigma or perceived HIV-related discrimination in health care settings. Research on group density has been applied to perceptions of racial discrimination and physical and mental health outcomes. It may be that group density effects related to race do not generalize to attitudes toward PLHIV, in the way that would have been predicted by the contact theory literature.28,30

The findings reported in this study should be interpreted with consideration that neighborhood racial diversity and income could be markers of other neighborhood characteristics, including liberal political views, social tolerance, and urbanism.46,47 Future research could merge neighborhood-level information with data on community attitudes (e.g., the General Social Survey,48 which we could not use due to very limited overlap in census tracts covered in it and our study) to determine whether specific community attitudes account for differences in perceived HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

In addition, the analyses presented in this study did not account for access to other PLHIV and WLHIV. Knowing other people who are living with HIV reduces HIV-related stigma among others regardless of HIV status.49 Thus, contact theory would still apply to these findings, but would pertain to knowing others with HIV rather than our explanation that more exposure to people of other races in a community translates to less stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors perceived by WLHIV. Future investigations could account for individuals' knowing other PLHIV and/or the HIV prevalence within neighborhoods to expand upon this explanation.

These findings imply that women in more racially homogenous neighborhoods are more vulnerable to internalized HIV stigma and perceived HIV-related discrimination. Socioeconomic disadvantage also increases internalized HIV stigma particularly in a higher income neighborhood. Stigma interventions may be most needed in racially homogenous communities with greater disparities in income. Interventions that encourage health care providers and patients to function as collaborative teams are an important approach as they would increase contact and discourage in-group separation.23,50,51

Indeed, a qualitative study of WLHIV found that participants wanted more communication with their health care providers and communities.52 Another investigation of HIV care engagement highlighted desires from patients to be more involved relationally with their care.53 Health care facilities may benefit most from interventions that bring together health care workers and PLHIV to address discrimination and stigma at the level of the health care setting.54 Scaling up HIV peer support may also be particularly important to provide support in coping with HIV-related stigma and discrimination.55 This may include a diverse team of peer navigators for matching based on patient racial and/or socioeconomic background.56

These contact interventions comprise important intervention targets at the interpersonal level, and structural-level interventions are also needed to combat stigma and discrimination. Policies protecting PLHIV from discrimination must continue to be enforced and advocated for, as well as communicating diversity values within communities and developing and disseminating inclusive media campaigns.57 Altogether, implementation of these interventions should be paired with assessment of experiences of stigma and discrimination along with health-related outcomes among PLHIV.

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. Chiefly, these results are cross-sectional, and we cannot draw causal inferences based on these findings. These associations should be interpreted as suggestions for future longitudinal investigations of neighborhood level variables and HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

Second, the measure of health care discrimination for this study assessed discrimination in any health care setting. WLHIV may access health care in a variety of settings within and outside of their communities. We used this measure as a proxy for broader experiences of discrimination, but future investigations could specify which settings women perceive discrimination in relation to where they reside. Further, while not all women in this study receive their medical care in the same setting as their WIHS study site, they do plausibly have access to the academic center resources and their experiences of stigma and discrimination may not generalize to all WLHIV, such as those in rural communities or without access to specialized HIV care.

Third, as mentioned earlier in our discussion we cannot account for other characteristics of neighborhoods outside of the census-level data collected here that may drive the associations we found. As more data on neighborhood-level characteristics that relate to HIV stigma and discrimination become available, researchers will be able to better characterize communities of risk.

Fourth, census tract variables and statistical analyses herein assumed a social categorical approach to race, which may not represent how women identify ethnically and culturally. Our approach to calculation of racial diversity was empirically informed, and it approximates racial diversity within the limits of the social construction of racial categories that do have implications where they are measured. Despite these limitations, this study builds on previous theoretical and empirical work to describe the social context where women perceive stigma and discrimination that warrants consideration in tailoring future interventions.

In summary, WLHIV who resided in less racially diverse neighborhoods reported higher levels of internalized HIV stigma and perceived more HIV-related discrimination in health care settings. Women living in more socioeconomically advantaged neighborhoods while having lower incomes themselves also reported more internalized HIV stigma. HIV stigma-reduction interventions may be most needed in racially homogenous communities with income disparities, and collaborations that increase contact between health care workers and WLHIV are particularly important to combat perceived discrimination and reduce internalized HIV stigma.

Acknowledgments

Data in this article were collected by the WIHS. WIHS (Principal Investigators): UAB-MS WIHS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-AI-103401; Atlanta WIHS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun, Anandi Sheth, and Gina Wingood), U01-AI-103408; Bronx WIHS (Kathryn Anastos and Anjali Sharma), U01-AI-035004; Brooklyn WIHS (Deborah Gustafson and Tracey Wilson), U01-AI-031834; Chicago WIHS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-AI-034993; Metropolitan Washington WIHS (Seble Kassaye and Daniel Merenstein), U01-AI-034994; Miami WIHS (Maria Alcaide, Margaret Fischl, and Deborah Jones), U01-AI-103397; UNC WIHS (Adaora Adimora), U01-AI-103390; Connie Wofsy Women's HIV Study, Northern California (Bradley Aouizerat and Phyllis Tien), U01-AI-034989; WIHS Data Management and Analysis Center (Gypsyamber D'Souza, Stephen Gange, and Elizabeth Golub), U01-AI-042590; Southern California WIHS (Joel Milam), U01-HD-032632 (WIHS I–WIHS IV). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health. WIHS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA), UL1-TR000454 (Atlanta CTSA), P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR), and P30-AI-027767 (UAB CFAR). The authors acknowledge the assistance of the WIHS program staff and the contributions of the participants who enrolled in this study. This study was funded by a WIHS substudy grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, R01MH104114. Trainee support was provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ 2T32HS013852-16).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Of the 189 women who identified their ethnicity as Hispanic, 60 (32%) identified their race as white, 29 (15%) identified their race as black, and 100 (53%) identified their race as other.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV Among Women. 2018. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women (Last accessed August14, 2018).

- 2. Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: A test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav 2013;17:1785–1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sayles JN, Hays RD, Sarkisian CA, Mahajan AP, Spritzer KL, Cunningham WE. Development and psychometric assessment of a multidimensional measure of internalized HIV stigma in a sample of HIV-positive adults. AIDS Behav 2008;12:748–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Loutfy MR, Logie CH, Zhang Y, et al. Gender and ethnicity differences in HIV-related stigma experienced by people living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. PloS One 2012;7:e48168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baugher AR, Beer L, Fagan JL, et al. Prevalence of internalized HIV-related stigma among HIV-infected adults in care, United States, 2011–2013. AIDS Behav 2017;21:2600–2608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lekas H-M, Siegel K, Schrimshaw EW. Continuities and discontinuities in the experiences of felt and enacted stigma among women with HIV/AIDS. Qual Health Res 2006;16:1165–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Darlington CK, Hutson SP. Understanding HIV-related stigma among women in the Southern United States: A literature review. AIDS Behav 2017;21:12–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bogart LM, Cowgill BO, Kennedy D, et al. HIV-related stigma among people with HIV and their families: A qualitative analysis. AIDS Behav 2008;12:244–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Latkin CA, German D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Neighborhoods and HIV: A social ecological approach to prevention and care. Am Psychol 2013;68:210–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rebeiro PF, Howe CJ, Rogers WB, et al. The relationship between adverse neighborhood socioeconomic context and HIV continuum of care outcomes in a diverse HIV clinic cohort in the Southern United States. AIDS Care 2018;30:1426–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shacham E, Lian M, Önen N, Donovan M, Overton E. Are neighborhood conditions associated with HIV management? HIV Med 2013;14:624–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Levi-Minzi MA, Chen M. Environmental influences on HIV medication adherence: The role of neighborhood disorder. Am J Public Health 2015;105:1660–1666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: A series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Rice WS, Turan JM. Framing mechanisms linking HIV-related stigma, adherence to treatment, and health outcomes. Am J Public Health 2017;107:863–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol 2001;27:363–385 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sayles JN, Ryan GW, Silver JS, Sarkisian CA, Cunningham WE. Experiences of social stigma and implications for healthcare among a diverse population of HIV positive adults. J Urban Health 2007;84:814–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: A review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav 2009;13:1160–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fazeli PL, Turan JM, Budhwani H, et al. Moment-to-moment within-person associations between acts of discrimination and internalized stigma in people living with HIV: An experience sampling study. Stigma Health 2017;2:216–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Turan B, Rogers AJ, Rice WS, et al. Association between perceived discrimination in healthcare settings and HIV medication adherence: Mediating psychosocial mechanisms. AIDS Behav 2017;21:3431–3439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rice WS, Crockett KB, Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Atkins GC, Turan B. Association between internalized HIV-related stigma and HIV care visit adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:482–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kay ES, Rice WS, Crockett KB, Atkins GC, Batey DS, Turan B. Experienced HIV-related stigma in health care and community settings: Mediated associations with psychosocial and health outcomes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;77:257–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: Moving toward resilience. Am Psychol 2013;68:225–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hunt MO, Wise LA, Jipguep M-C, Cozier YC, Rosenberg L. Neighborhood racial composition and perceptions of racial discrimination: Evidence from the Black Women's Health Study. Soc Psychol Q 2007;70:272–289 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. People like us: Ethnic group density effects on health. Ethn Health 2008;13:321–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Halpern D, Nazroo J. The ethnic density effect: Results from a national community survey of England and Wales. Int J Soc Psych 2000;46:34–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oliver JE, Wong J. Intergroup prejudice in multiethnic settings. Am J Pol Sci 2003;47:567–582 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J Pers Soc Psychol 2006;90:751–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. Eur J Soc Psychol 2008;38:922–934 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR, Wagner U, Christ O. Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. Int J Intercult Relat 2011;35:271–280 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Allport GW, Clark K, Pettigrew T. The Nature of Prejudice. Oxford, England: Addison-Wesley, 1954

- 32. Tropp LR. Perceived discrimination and interracial contact: Predicting interracial closeness among Black and White Americans. Soc Psychol Q 2007;70:70–81 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21:283–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Adimora AA, Ramirez C, Benning L, et al. Cohort profile: The Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). Int J Epidemiol 2018;47:393i–394i [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10. [computer program]. Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 36. US Census Bureau. American Community Survey. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau, 2010

- 37. Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health 2001;24:518–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bunn JY, Solomon SE, Miller C, Forehand R. Measurement of stigma in people with HIV: A reexamination of the HIV Stigma Scale. AIDS Educ Prev 2007;19:198–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dos Santos MM, Kruger P, Mellors SE, Wolvaardt G, Van Der Ryst E. An exploratory survey measuring stigma and discrimination experienced by people living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa: The People Living with HIV Stigma Index. BMC Public Health 2014;14:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1576–1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nai J, Narayanan J, Hernandez I, Savani K. People in more racially diverse neighborhoods are more prosocial. J Pers Soc Psychol 2018;114:497–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Simpson E, Sutherland G, Blackwell D. Measurement of diversity. Nature 1949;163:688 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2013

- 44. MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods 2002;7:83–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Turan JM, Elafros MA, Logie CH, et al. Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Med 2019;17:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sharp EB, Joslyn MR. Culture, segregation, and tolerance in urban America. Soc Sci Q 2008;89:573–591 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nyden P, Maly M, Lukehart J. The emergence of stable racially and ethnically diverse urban communities: A case study of nine U.S. cities. Housing Policy Debate 1997;8:491–534 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Smith TW, Davern M, Freese J, Hout M, General Social Surveys, 1972–2016 [machine-readable data file]/Principal Investigator, Smith TW; Co-Principal Investigators, Marsden PV, Hout M; Sponsored by National Science Foundation.—NORC, ed.—Chicago: NORC; 2018. NORC at the University of Chicago [producer and distributor]. Data accessed from the GSS Data Explorer. Available at: https://gssdataexplorer.norc.org

- 49. Prati G, Zani B, Pietrantoni L, et al. The role of knowing someone living with HIV/AIDS and HIV disclosure in the HIV stigma framework: A Bayesian mediation analysis. Qual Quant 2016;50:637–651 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Penner LA, Gaertner S, Dovidio JF, et al. A social psychological approach to improving the outcomes of racially discordant medical interactions. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:1143–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nyblade L, Stockton MA, Giger K, et al. Stigma in health facilities: Why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Med 2019;17:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Amutah-Onukagha N, Mahadevan M, Opara I, Rodriguez M, Trusdell M, Kelly J. Project THANKS: Examining HIV/AIDS-related barriers and facilitators to care in African American women: A community perspective. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2018;32:119–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Taylor BS, Fornos L, Tarbutton J, et al. Improving HIV care engagement in the south from the patient and provider perspective: The role of stigma, social support, and shared decision-making. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2018;32:368–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Batey DS, Whitfield S, Mulla M, et al. Adaptation and implementation of an intervention to reduce HIV-related stigma among healthcare workers in the United States: Piloting of the FRESH Workshop. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2016;30:519–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rao D, Kemp CG, Huh D, et al. Stigma reduction among African American women with HIV: UNITY health study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;78:269–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mugavero MJ, Saag MS, Norton WE. Health care system and policy factors influencing engagement in HIV medical care: Piecing together the fragments of a fractured health care delivery system. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:S238–S246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cook JE, Purdie-Vaughns V, Meyer IH, Busch JT. Intervening within and across levels: A multilevel approach to stigma and public health. Soc Sci Med 2014;103:101–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]