Abstract

Background:

The etiopathogenesis of electrocardiographic bundle branch (BB) and atrioventricular (AV) blocks is not fully understood. We investigated familial clustering of cardiac conduction defects and pacemaker insertion in the Framingham Heart study (FHS). Additionally, we assessed familial clustering of pacemaker insertion in the Danish general population.

Methods:

In FHS, we used multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models to investigate the association of parental AV block (PR interval ≥0.2 sec), complete BB block (QRS ≥0.12 sec) or pacemaker insertion with the occurrence of cardiac conduction abnormalities in their offspring. The Danish nationwide administrative registries were interrogated to assess the relations of parental pacemaker insertion with offspring pacemaker insertion.

Results:

In FHS (n=371 cases with first degree AV block, complete BB block or pacemaker insertion, and 1471 age- and sex-matched controls), individuals with at least one affected parent with a conduction defect had a 1.65-fold odds (odds ratio [OR], 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.32-2.07) for manifesting an AV block, and a 1.62-fold odds (95% CI 1.08-2.42) for developing a complete BB block. If at least one parent had any electrocardiographic conduction defect or pacemaker insertion, the offspring had a 1.62-fold odds (95% CI 1.31-2.00) for experiencing any of these conditions. In Denmark (n=2,824,199 individuals; 5397 incident pacemaker implantations), individuals with at least one first-degree relative with history of pacemaker insertion had a multivariable-adjusted 1.68-fold (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 95% CI 1.49-1.89) risk of undergoing a pacemaker insertion. If the affected relative was ≤45 years of age, the IRR was markedly increased to 51.0 (95% CI 32.7-79.9).

Conclusion:

Cardiac conduction blocks and risk for pacemaker insertion cluster within families. A family history of conduction system disturbance or pacemaker insertion should trigger increased awareness of a similar propensity in other family members, especially so when the conduction system disease occurs at a younger age.

Journal Subject Terms: Arrhythmias, Pacemaker, Epidemiology

Keywords: atrioventricular block, bundle-branch block, pacemaker, family study, familial clustering

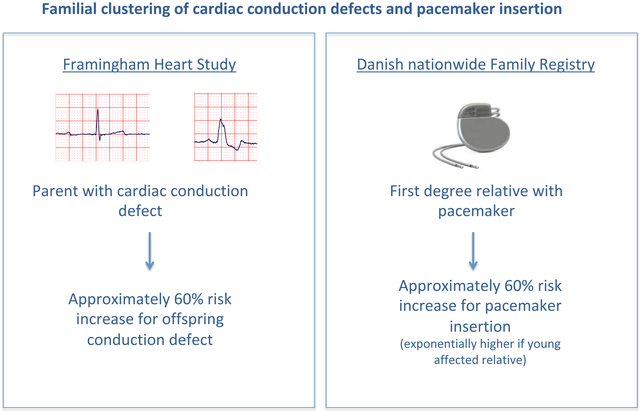

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Cardiac conduction abnormalities are a relatively common finding in clinical practice.1 Although considered benign in a clinical setting, the presence of a first degree AV block is associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation, pacemaker insertion, and mortality.2, 3 Higher degree AV block can result in bradycardia, and often to syncopal episodes; urgent pacemaker insertion is indicated in these cases.4 Complete left bundle branch (BB) block and –to a lesser extent – complete right BB block have been associated with an increased risk of future AV block, and also with increased mortality risk.5-7 Despite their clinical and prognostic importance, the etiopathogenesis of both AV and BB block are not fully understood.

We hypothesized that electrocardiographic conduction system disturbances (including pacemaker insertion) cluster within families, and an earlier onset of conduction system disturbance may be a marker of genetic predisposition to the condition. Accordingly, we investigated if cardiac conduction defects and pacemaker insertion cluster within families in the Framingham Heart study (FHS). Additionally, given the limited ability to evaluate familial aggregation of pacemaker insertion in FHS (due to constraints of sample size), we assessed if there was evidence for a familial clustering of pacemaker insertion in the general population of Denmark.

Methods

The data and study materials of the Framingham Heart study are not currently available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results. The procedure for requesting data from the Framingham Heart Study can be found at https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org.

Data of the Denmark National family registry are held by Statistics Denmark, where authorized research groups can be granted access. Due to Danish laws, data cannot be distributed outside of these research environments. Use of data may be possible through collaboration with a Danish research group.

Study samples

Schematic overviews of the study samples are available in the Supplemental material (Figures 1-3). Details are provided below.

Framingham Heart Study

The design and recruitment criteria of the Framingham Heart study (FHS) have been previously described. 8, 9 The present investigation incorporated data from multiple generations in the FHS to create a nested case-control sample. Specifically, we used two parental cohorts in the Framingham Study, the Original and Offspring cohorts, and two descendant cohorts, the Offspring and Generation 3 cohorts. The Offspring cohort includes children of the Original cohort and their spouses, and the Generation 3 cohort comprises children of the Offspring cohort and their spouses. Of the 5124 Offspring cohort participants, 811 had both parents enrolled in the Original cohort and attended at least one examination between examination cycles 2 (1979–1983) and 9 (2011–2014), and were eligible for inclusion in our study sample. Similarly, of the 4095 participants in the Generation 3 cohort, 2458 had both parents in the Offspring cohort and attended at least one of their first two examination cycles, making them eligible for inclusion in the present investigation.

Denmark

Danish nationwide family registry Information on parents have been registered on all births in Denmark since 1954 and information is available in the Danish nationwide family registry. For the present study, all individuals in Denmark born after 1953 with information available on both parents were included in the present study. Adoptees were excluded. Identification of pacemaker implantation (January 1, 1994 to December 31, 2015) was done using procedural codes from the Danish hospitalization registry (SKS operational codes KFPF or BFCA, excluding BFCA5 [pacemaker with implantable cardioverter], as the latter type of pacemaker is often inserted as a primary prophylactic therapy). The Danish hospitalization registry was also used to identify selected comorbidities of possible importance for the risk of having a pacemaker implanted, i.e., congestive heart failure (ICD-10 codes I11.0, I42, I50), ischemic heart disease (I20-I25), and atrial fibrillation (I48). We also identified possible causes for pacemaker implantation as overall AV or bundle branch block (I44, I45), first-degree AV block (I44.0), second-degree AV block (I44.1), third degree AV block (I44.2), trifascicular block (I45.3), left bundle branch block (I44.7), and sick sinus syndrome (I49.5). Using the Danish prescription registry, where all claimed prescriptions from Danish pharmacies are registered since 1995, we also identified use of beta-blockers (ATC code C07), digoxin (C01AA), calcium channel blockers (C08), and amiodarone (C01BD). Additionally, diabetes was defined as use of antidiabetic drugs (A10).

Definitions of Endpoints in FHS

Given that AV block II° and III° without pacemaker is a very rare finding in our ambulatory follow-up FHS examination center, we decided to use I° AV block (PR ≥0.2 sec) as a marker of AV conduction abnormality. Complete bundle branch (BB) block was defined as QRS width ≥0.12 sec (without distinguishing right vs. left BB blocks). Presence of an implanted pacemaker was addressed in our standardized FHS examination questionnaire, and verified by evaluating participants’ electrocardiographic tracings and /or details of the pacemaker implantation procedures by an adjudication panel consisting of 3 physicians.

Definition of Endpoint in Denmark

Having a first-time pacemaker implantation, based on the Danish hospitalization registry, as described above.

Ethics Approval

All FHS participants gave their written, informed consent before participating. The study was also approved by the institutional review board of the Boston University’s School of Medicine. In Denmark, no ethical approval are needed for registry-based studies, in which no individuals are identifiable. The Danish study was approved by the Danish data protection agency (ref. 2007–58-0015 / GEH-2014–013 I-Suite no: 02731).

Statistical analyses

FHS

Using data from the parental cohorts (Original and Offspring), the independent variable of interest was parental presence of AV block, complete BB block, and/or pacemaker insertion. To consider a descendant exposed at least one of his or her parents must have developed an AV Block, complete BB block, or had a pacemaker inserted prior to the descendant’s own development (or lack thereof) of an AV block, or a BB block, or undergone pacemaker insertion. Using parental exposure information, we created four exposure variables: any parental presence of AV block, complete BB block, or pacemaker insertion; presence of these conditions in the mother, or in the father; and the number of parents (coded as 0,1,2) with at least one of the electrocardiographic conditions. We modeled three dependent (outcome) variables in the descendant: (1) development of an AV block, (2) development of complete BB block, and (3) a composite of AV block, complete BB block or pacemaker insertion. We could not model pacemaker insertion alone due insufficent number of informative families.

We ascertained evidence of AV block, complete BB block, and/or pacemaker insertion in each cohort at the following examination cycles: Original cohort examination cycles 15 (1977–1979) through 23 (1992–1996); Offspring cohort examination cycles 2 (1979–1983) through 9 (2011–2014); and Generation 3 examination cycles 1 (2002–2005) and 2 (2008–2011). Participant-exams among those with prevalent atrial fibrillation were excluded. At descendant examination cycles (Offspring and Generation 3), covariates were also ascertained, and descendant participants were excluded from examinations if they were missingcovariates. This process yielded 371 ‘cases’ with AV block, complete BBB or pacemaker insertion.

We matched each of the cases in the descendant cohorts on sex and within 2 years of age to at most 4 other attendees (controls) at the same examination cycle as the case but without evidence of electrocardiographic findings of conduction system disease or a history of pacemaker insertion. Because cases and controls were matched at each examination cycle, an individual who transitioned from control to case status at exam m was eligible for being part of the control pool for the prior m-1 examination cycles. A descendant was only included as a case at the first examination at which he or she had electrocardiographic evidence of an AV block or complete BB block or had a pacemaker inserted. After this first occurrence and being designated as a case, descendants were excluded from the sample at future examination cycles. We also estimated sibling recurrence risk ratio as another measure of the heritability of AV block, complete BB block, and pacemaker insertion. Sibling recurrence risk ratio was calculated as the sibling recurrence risk (measured in %) divided by the prevalence of the condition in the total Framingham sample.

Once the sample was assembled and controls were matched to cases, we analyzed the data using conditional logistic regression models to account for matching, fitting one model for each of the 4 parental exposure variables (see above), where development of AV block, BB block, and/or pacemaker insertion in the descendants served as the dependent outcome variable. In addition to accounting for the matching design, models were adjusted for standard cardiovascular risk factors, i.e. systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication, diabetes mellitus, current smoking status, the ratio of total to high density lipoprotein cholesterol, prevalent cardiovascular disease, and use of betablockers and/or antiarrhythmic drugs. Since an individual could potentially appear in the sample multiple times as a control at different examinations, we used a robust sandwich estimator to account for intra-individual correlations. In sensitivity analyses, we excluded participants on betablockers or antiarrhythmic drugs.

Denmark

All individuals without a prior pacemaker insertion between 1994 and 1996 were followed from their 20th birthday or the 1st of January 1997, whichever came first. People were followed for pacemaker insertion until maximally December 31, 2015, their date of death, or the date of pacemaker implantation. Exposure status in relation to the presence of comorbidities, use of medications, and having a first-degree family member with pacemaker was updated continuously, i.e., individuals were classified as having these conditions only after they had occurred. Poisson regression models adjusted for numbers of siblings were estimated in two steps to investigate the risk of having a pacemaker implanted. In the first step, we adjusted for sex and age (updated annually). In the second model, we additionally adjusted for the presence of congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, ischemic heart disease and ‚ever’ use of beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, and amiodarone. As a sensitivity analysis, we excluded people exposed to any of these antiarrythmic drugs. Because familial risk may differ according to the age at onset of disease in the proband, we tested for a statistical interaction between having a first-degree relative with a pacemaker and the age at which the pacemaker was implanted. Secondary analyses were stratified by age into 3 age-groups (≤45 years, >45–55 years, and >55 years, respectively) due to a statistically significant effect modification by the proband’s age for the risk of having an implanted pacemaker (p<0.0001). To investigate baseline characteristics of people having a pacemaker implanted and to assess how they may differ from people who did not have a pacemaker implanted, up to 5 age- and sex-matched controls were randomly sampled from the source population using a risk set approach. In this approach, controls were assigned their respective cases’ implanted pacemaker date to identify comorbidity and medication use. As sensitivity, conditional logistic regression analyses, comparable with those used to analyze FHS data, were performed.

All analyses in both cohorts were performed in SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC), and 2-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Dres Vasan and Duncan had access to all FHS data and take responsibility for data integrity. Dr Andersson had access to all Danish registry data used in the present analysis.

Results

FHS

Characteristics of the FHS study sample, partitioned by case-control status, are provided in Table 1. We identified 371 individuals with first degree AV block, BB block, or pacemaker insertion (referred to as cases).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Framingham sample by case-control status

| Characteristic | Cases (n=371) |

Controls (n=1471) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 47.8 ± 11.0 | 47.4 ± 10.7 |

| Female sex | 130 (35.0) | 517 (35.1) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 119.6 ± 15.5 | 119.9 ± 15.0 |

| Antihypertensive medication | 50 (13.5) | 179 (12.2) |

| Total/HDL cholesterol | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 4.1 ± 1.9 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 21 (5.7) | 50 (3.4) |

| Current smoking | 53 (14.3) | 223 (15.2) |

| Myocardial infarction | 5 (1.4) | 10 (0.7) |

| Heart failure | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.3) |

| Prevalent cardiovascular disease | 12 (3.2) | 34 (2.3) |

| Framingham cohort | --- | --- |

| Offspring | 169 (45.6) | 666 (45.3) |

| Generation 3 | 202 (54.5) | 805 (54.7) |

| At least one parent affected* | 232 (62.5) | 731 (49.7) |

| Mother affected* | 112 (30.2) | 323 (22.0) |

| Father affected* | 176 (47.4) | 554 (37.7) |

| Number of parents affected* | --- | --- |

| 0 | 139 (37.5) | 740 (50.3) |

| 1 | 176 (47.4) | 585 (39.8) |

| 2 | 56 (15.1) | 146 (9.9) |

Case status was defined as being affected by AV block, BB block, or pacemaker insertion. Summary statistics for continuous variables are displayed as mean ± standard deviation, categorical variables are displayed as N (%).

affected by AV block (n=295), BB block (n=77), or pacemaker insertion (n=8). 9 affected parents had both an AV Block and BB block.

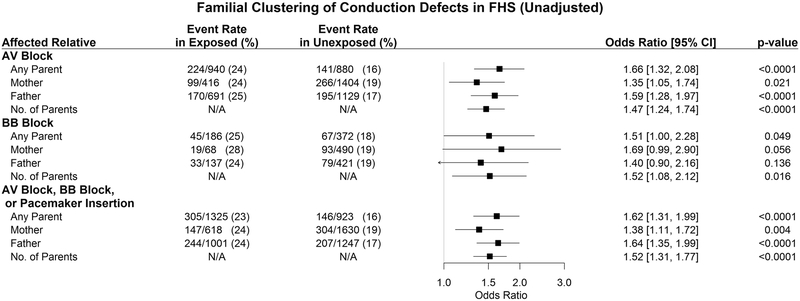

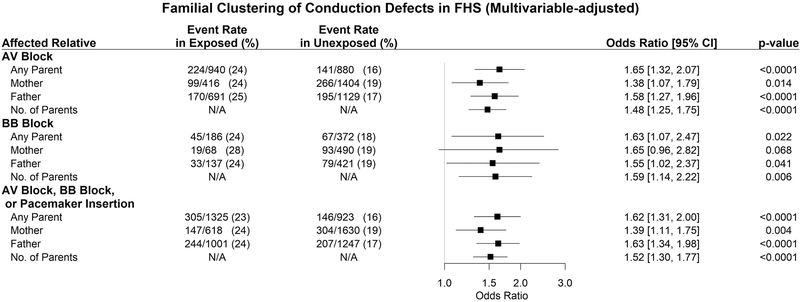

As shown in Figure 1A, participants with at least one parent affected by an AV block had 1.66 times the odds (p<0.0001) of developing an AV block. Similarly, participants with at least one parent with a complete BB block had a 1.63-fold odds (p=0.019) of developing a complete BB block. Furthermore, if at least one parent was affected by either a conduction block or pacemaker insertion, the offspring had a 1.62-fold odds (p<0.0001) of developing a conduction disturbance or undergoing a pacemaker insertion. Multivariable adjustment did not substantively change these observations (Figure 1B). Also, these findings remained robust in sensitivity analyses excluding participants on antiarrhythmic drugs (data not shown).

Figure 1: Familial Clustering of cardiac conduction defects in FHS.

Forest plots show univariable (Panel A) and multivariable adjusted (Panel B) odds ratios for offspring conduction defects (or pacemaker insertion) with 95% confidence intervals.

Sibling recurrence risk ratio estimates for AV block, BB block, and pacemaker insertion are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sibling recurrence risk, prevalence in the population, and sibling recurrence risk ratio.

| Sibling recurrence risk (%) |

Prevalence in the population (%) |

Sibling recurrence risk ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| AV block, BB block, or pacemaker implantation | 42.93% | 12.67% | 3.39 |

| AV block | 41.43% | 10.30% | 4.02 |

| BB block | 35.29% | 3.22% | 10.96 |

Familial clustering of pacemaker insertion in Denmark

We identified 2,824,199 individuals eligible for inclusion in the present study. Of these, 5,397 had a pacemaker implanted during follow-up over the period defined above. Characteristics of people with implanted pacemakers and controls are shown in Table 3. The mean age at pacemaker implantation was 45 years, and 30% were women. Totally 6% and 17% had a diagnosis of second and third degree AV block registered, respectively. Additionally 13% had a diagnosis of sick sinus syndrome. Compared with matched controls, individuals with a pacemaker implanted had a higher prevalence of congestive heart failure (22% vs. 1%), ischemic heart disease (25% vs. 3%), diabetes (9% vs. 4%), and atrial fibrillation (18% vs. approximately 1%, all p<0.05). Individuals with and without a first-degree family member with pacemaker were overall comparable in terms of clinical characteristics, both among those who had pacemakers implanted and among the matched controls, Supplemental Table 1.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Danish registry sample by case-control status

| Characteristic | Cases (n=4757) | Controls (n=23780) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 44.6 (4.0) | 44.6 (4.0) |

| Female sex | 1446 (30) | 7225 (30) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1171 (25) | 610 (3) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 869 (18) | 318 (1) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1039 (22) | 256 (1) |

| Diabetes | 442 (9) | 876 (4) |

| BBB or AV block | 1577 (33) | 59 (0.3) |

| AV block 1st degree | 43 (0.9) | ≤3 |

| AV block 2nd degree | 283 (6.0) | ≤3 |

| AV block 3rd degree | 791 (17) | ≤3 |

| Trifasicular block | 17 (0.4) | ≤3 |

| Left bundle branch block | 59 (1.2) | ≤3 |

| Sick sinus syndrome | 610 (13) | ≤3 |

| Medication use (ever use): | ||

| Calcium channel blocker | 1015 (21) | 1882 (8) |

| Beta blocker | 1937 (41) | 2655 (11) |

| Digoxin | 403 (8) | 127 (0.5) |

| Amiodarone | 233 (5) | 79 (0.3) |

| Sibling with pacemaker | 41 (0.9) | 56 (0.2) |

| Father with pacemaker | 114 (2.0) | 487 (2.1) |

| Mother with pacemaker | 107 (2.3) | 349 (1.5) |

| At least one relative affected | 254 (5.3) | 880 (3.7) |

Case status was defined by having a pacemaker. Summary statistics for continuous variables are displayed as mean ± standard deviation, categorical variables are displayed as N (%). Values of ≤3 individuals are not presented in detail, as per Danish law low numbers may not be published.

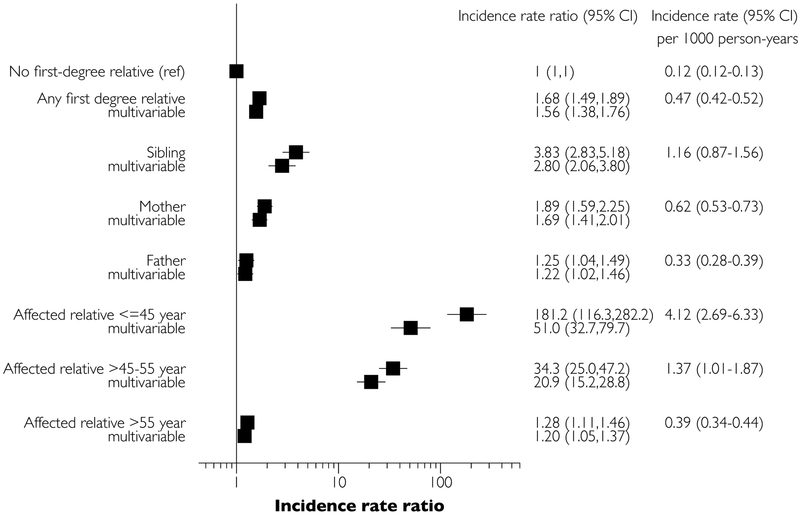

Crude incidence rates, sex- and age-adjusted, and multivariable-adjusted incidence rate ratios of pacemaker insertion are provided in Figure 2. Individuals without an affected first-degree relative had an incidence of 1 per 10,000 person-years for pacemaker insertion, whereas individuals with at least one affected first-degree relative had an incidence of 3.9 per 10,000 person-years. The highest rate of pacemaker implantation was observed in those with an affected sibling (incidence 11 per 10,000 person-years).

Figure 2: Familial clustering of pacemaker insertion in Denmark.

Forest plot shows age-sex-adjusted and multivariable adjusted incidence rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals for pacemaker insertion.

In an age- and sex-adjusted model, any affected first-degree relative conferred an incidence rate ratio of 1.68 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.49–1.89) for pacemaker insertion, compared to those without an affected first-degree relative (referent). Individuals with an affected sibling had an even higher incidence rate ratio of pacemaker implantation (3.83, 95% CI 2.83–5.18). If the affected relative was ≤45 years of age at the time of pacemaker implantation, the incidence rate ratio was increased to 181 (95% CI 116–282; N=21 events). If the affected relative was 45–55 years of age at time of pacemaker insertion, the incidence rate ratio was increased to 34.3 (95% CI 25.0–47.2; N=40 events). These findings were largely maintained in multivariable-adjusted analyses, although the incidence rate ratios for individuals with young probands were partly attenuated: individuals with an affected relative aged <45 years had a multivariable adjusted 51.0-fold risk (95% CI 32.7–79.9) for pacemaker insertion. Censoring individuals with use of antiarrhythmic agents did not alter the results significantly; incidence rate ratio 1.53 (95% CI 1.28–1.83) for any first-degree relative, 3.32 (95% CI 2.06–5.37) for siblings, 1.64 (95% CI 1.24–2.17) for mothers, and 1.24 (95% CI 0.96–1.60) for fathers, compared with not having a first-degree relative with pacemaker. Further censoring upon a diagnosis of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, or ischemic heart disease did also not influence the results significantly, incidence rate ratio 1.63 (95% CI 1.32–2.02) for any first-degree relative, 2.91 (95% CI 1.56–5.42) for siblings, 1.75 (95% CI 1.26–2.43) for mothers, and 1.39 (95% CI 1.04–1.87) for fathers, compared with having no familial disposition. Conditional logistic regression models of the matched sample yielded similar results to the main analyses, see Supplemental Table 2.

Discussion

Main findings

In the present study, we investigated the potential familial clustering of AV block, complete BB block and pacemaker insertion. We observed that parental AV or complete BB block conferred an approximately 60% increased odds of offspring AV and complete BB block, respectively. In the Danish general population, individuals with a first-degree relative affected by pacemaker insertion had more than 50% increased risk for undergoing a pacemaker insertion, after multivariable adjustment. This risk exponentially increased further – reaching a 50-fold risk increase - if the affected relative was young, or if he/she was a sibling, the latter probably being consistent with the lower age among siblings than among parents, given the cohort design (i.e., only including individuals born after 1953).

Existing literature

Many heart rhythm disorders are heritable.10, 11 Previous investigations have demonstrated a substantial heritability of the PR interval, with estimates ranging from 30–50%. 12-16 Less is known about heritability of clinical AV blocks. Baruteau et al. investigated parental conduction disturbances of 141 children with nonimmune isolated AV block, a rare pediatric condition. 17 They observed that 50.8% of parents had cardiac conduction abnormalities, as compared to 4.6% of control parents. Our investigation extends these previous studies by providing risk estimates for first-degree relatives of individuals with an AV block depending on the parental exposure status in a large community-based sample.

Heritability estimates of QRS duration have been less consistent, ranging from 0 to approximately 0.5. 13, 16, 18-20 Our investigation extends these data by demonstrating a familial aggregation of electrocardiographic complete BB blocks.

Pacemaker insertion is the therapeutic consequence of severe cardiac conduction defects in many cases. However, despite its high clinical relevance, we are not aware of any previous work investigating the familial clustering of pacemaker insertions. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, the present investigation is the first to demonstrate that not only electrocardiographic conduction delays, but also pacemaker insertion have a strong familial component in the general population. Of note, our risk estimates remained highly statistically significant after multivariable adjustment for potential confounders (including congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease, and anti-arrhythmic drugs), suggesting that the observed familial clustering of pacemaker insertions may in part have a genetic basis. Particularly striking is the observation that the familial association increased markedly if the affected relative was of younger age (at time of pacemaker insertion) or a sibling. This may suggest that pacemaker insertion at younger age often has a strong genetic background. However, other shared environmental risks should at least be considered, e.g., exposure to ticks with resulting Lyme disease with cardiac involvement.

Implications

Our findings may have both pathophysiological and clinical implications. From a pathophysiological standpoint, our observations should encourage additional studies to delineate the genetic basis of advanced cardiac conduction blocks (as opposed to studies of electrocardiographic intervals within the normal range). Of note, currently known genetic variants derived from genome-wide association studies explain only a very small fraction of the heritability of PR interval and QRS width. 16, 21 Since pacemaker insertion is an uncommon event, pooled studies of multiple large cohorts with GWAS data and appropriate stratification by indication for pacemaker insertion may offer further clues to the genetic architecture of AV blocks and BB requiring pacemaker insertion. Notably, the risk ratios observed in our study for parental conduction system disease or pacemaker insertion correspond to similar relative risks observed for coronary artery disease (CAD) in the context of a parental or sibling with history of CAD.22 Such initial observations of familial aggregation of risk for CAD spurred numerous subsequent GWAS studies and the discovery of >50 genetic loci that determine disease susceptibility. Thus, our demonstration of familial aggregation of conduction system disease may be an important first step in this direction.

For clinicians, our risk estimates associated with familial exposure to AV or complete BB block may be more informative than previously reported heritabilities of continuous PR interval and QRS width, respectively. Specifically, our findings should raise the suspicion of cardiac conduction defects in patients with a known familial background of AV block, complete BB block or pacemaker insertion, in particular when a sibling or a younger relative is affected. As such, we speculate that periodic electrocardiographic screening and prolonged cardiac monitoring could be considered in patients with unclear syncopal episodes who have a younger first-degree relative with an implanted pacemaker, a premise that warrants further investigation. Such investigations will also shed light on the positive and negative predictive values of familial information on conduction system disease for the occurrence of similar outcomes in the offspring or siblings both in the settings of screening examinations of asymptomatic individuals and diagnostic encounters of patients presenting with syncope.

Strengths and Limitations

The use of two complementary datasets with similar findings strengthen our investigation. The consistency of results across several analyses and across the studies reduce the possibility of a chance finding. The FHS cohort is unique by virtue of its sequential electrocardiography in its transgenerational cohorts, which facilitates ascertainment of conduction system disease over the lifecourse of individuals. The large administrative Danish database offers excellent power to evaluate familial clustering of uncommon but clinically relevant sequel of conduction system disturbances, i.e., pacemaker insertion.

There are some limitations of our investigation that must be acknowledged. First, in order to maximize our statistical power, we did not differentiate between complete left and right BB blocks. Future studies of larger pooled cohorts can help elucidate differences in risks conferred by parental right vs. left vs. indeterminate BB. Second, we used presence of a I° AV block as a marker of AV conduction because more advanced AV blocks (II° and III° without implanted pacemakers) are a rare finding in the ambulatory Framingham cohort. Third, our findings for individuals with younger affected relatives in Denmark are based on relatively few individuals, resulting in large confidence intervals. Nevertheless, the very high risk estimates and the consistency across subgroups underscore an important association. Fourth, although the diagnostic codes indicative of the reason for pacemaker implantation may be accurate,23 many patients had no registered cause. The lack of an exact reason for pacemaker implantation for some individuals in the national Danish database must be acknowledged as a limitation; for instance, it is likely that some patients with sinus node dysfunction received a pacemaker in addition to others with an AV or bundle branch block). Last, both our study samples were white individuals of European ancestry, and the Danish registry sample included only subjects born after 1954. Thus, the generalizability of our findings to other ethnicities and age groups remains to be evaluated.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, the present investigation is the first large-scale epidemiological study to establish and quantify familial clustering of cardiac conduction defects including pacemaker insertion in the general population, including by age-of-onset of the conduction system disorder and by genetic distance (risks in siblings). We observed a strong familial component to the occurrence of these conditions. Our findings may inform both basic scientists and clinicians.

Supplementary Material

What is known?

Cardiac conduction defects have a heritable component

What the study adds?

Parental atrioventricular (AV) or complete bundle branch (BB) block confers an approximately 60% increased odds of offspring AV and complete BB block

Individuals with a first-degree relative affected by pacemaker insertion have an approximately 60% increased risk for undergoing a pacemaker insertion

This risk exponentially increases if the affected relative is young

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts N01-HC-25195 and HHSN268201500001I. Dr. Vasan was also funded by the Evans Foundation and Jay and Louise Coffman Endowment at Boston University.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References:

- 1.Haataja P, Nikus K, Kahonen M, Huhtala H, Nieminen T, Jula A, Reunanen A, Salomaa V, Sclarovsky S, Nieminen MS, Eskola M. Prevalence of ventricular conduction blocks in the resting electrocardiogram in a general population: The health 2000 survey. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1953–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng S, Keyes MJ, Larson MG, McCabe EL, Newton-Cheh C, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Vasan RS, Wang TJ. Long-term outcomes in individuals with prolonged pr interval or first-degree atrioventricular block. JAMA. 2009;301:2571–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwok CS, Rashid M, Beynon R, Barker D, Patwala A, Morley-Davies A, Satchithananda D, Nolan J, Myint PK, Buchan I, Loke YK, Mamas MA. Prolonged pr interval, first-degree heart block and adverse cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2016;102:672–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brignole M, Auricchio A, Baron-Esquivias G, Bordachar P, Boriani G, Breithardt OA, Cleland J, Deharo JC, Delgado V, Elliott PM, Gorenek B, Israel CW, Leclercq C, Linde C, Mont L, Padeletti L, Sutton R, Vardas PE, Guidelines ESCCfP, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Document R, Kirchhof P, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Badano LP, Aliyev F, Bansch D, Baumgartner H, Bsata W, Buser P, Charron P, Daubert JC, Dobreanu D, Faerestrand S, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Le Heuzey JY, Mavrakis H, McDonagh T, Merino JL, Nawar MM, Nielsen JC, Pieske B, Poposka L, Ruschitzka F, Tendera M, Van Gelder IC, Wilson CM. 2013 esc guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: The task force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the european society of cardiology (esc). Developed in collaboration with the european heart rhythm association (ehra). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2281–2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson P, Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A. Bundle-branch block in middle-aged men: Risk of complications and death over 28 years. The primary prevention study in goteborg, sweden. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2300–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haataja P, Anttila I, Nikus K, Eskola M, Huhtala H, Nieminen T, Jula A, Salomaa V, Reunanen A, Nieminen MS, Lehtimaki T, Sclarovsky S, Kahonen M. Prognostic implications of intraventricular conduction delays in a general population: The health 2000 survey. Ann Med. 2015;47:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiong Y, Wang L, Liu W, Hankey GJ, Xu B, Wang S. The prognostic significance of right bundle branch block: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38:604–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannel WB, Dawber TR, Kagan A, Revotskie N, Stokes J, 3rd. Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease--six year follow-up experience. The framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1961;55:33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110:281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holm H, Gudbjartsson DF, Sulem P, Masson G, Helgadottir HT, Zanon C, Magnusson OT, Helgason A, Saemundsdottir J, Gylfason A, Stefansdottir H, Gretarsdottir S, Matthiasson SE, Thorgeirsson GM, Jonasdottir A, Sigurdsson A, Stefansson H, Werge T, Rafnar T, Kiemeney LA, Parvez B, Muhammad R, Roden DM, Darbar D, Thorleifsson G, Walters GB, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Arnar DO, Stefansson K. A rare variant in myh6 is associated with high risk of sick sinus syndrome. Nat Genet. 2011;43:316–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lubitz SA, Yin X, Fontes JD, Magnani JW, Rienstra M, Pai M, Villalon ML, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Levy D, Larson MG, Ellinor PT, Benjamin EJ. Association between familial atrial fibrillation and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2010;304:2263–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanson B, Tuna N, Bouchard T, Heston L, Eckert E, Lykken D, Segal N, Rich S. Genetic factors in the electrocardiogram and heart rate of twins reared apart and together. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:606–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Havlik RJ, Garrison RJ, Fabsitz R, Feinleib M. Variability of heart rate, p-r, qrs and q-t durations in twins. J Electrocardiol. 1980;13:45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newton-Cheh C, Guo CY, Wang TJ, O’Donnell C J, Levy D, Larson MG. Genome-wide association study of electrocardiographic and heart rate variability traits: The framingham heart study. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8 Suppl 1:S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilia G, Chen WM, Scuteri A, Orru M, Albai G, Dei M, Lai S, Usala G, Lai M, Loi P, Mameli C, Vacca L, Deiana M, Olla N, Masala M, Cao A, Najjar SS, Terracciano A, Nedorezov T, Sharov A, Zonderman AB, Abecasis GR, Costa P, Lakatta E, Schlessinger D. Heritability of cardiovascular and personality traits in 6,148 sardinians. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva CT, Kors JA, Amin N, Dehghan A, Witteman JC, Willemsen R, Oostra BA, van Duijn CM, Isaacs A. Heritabilities, proportions of heritabilities explained by gwas findings, and implications of cross-phenotype effects on pr interval. Hum Genet. 2015;134:1211–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baruteau AE, Behaghel A, Fouchard S, Mabo P, Schott JJ, Dina C, Chatel S, Villain E, Thambo JB, Marcon F, Gournay V, Rouault F, Chantepie A, Guillaumont S, Godart F, Martins RP, Delasalle B, Bonnet C, Fraisse A, Schleich JM, Lusson JR, Dulac Y, Daubert JC, Le Marec H, Probst V. Parental electrocardiographic screening identifies a high degree of inheritance for congenital and childhood nonimmune isolated atrioventricular block. Circulation. 2012;126:1469–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russell MW, Law I, Sholinsky P, Fabsitz RR. Heritability of ecg measurements in adult male twins. J Electrocardiol. 1998;30 Suppl:64–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Huo Y, Zhang Y, Fang Z, Yang J, Zang T, Xu X, Xu X. Familial aggregation and heritability of electrocardiographic intervals and heart rate in a rural chinese population. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2009;14:147–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mutikainen S, Ortega-Alonso A, Alen M, Kaprio J, Karjalainen J, Rantanen T, Kujala UM. Genetic influences on resting electrocardiographic variables in older women: A twin study. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2009;14:57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sotoodehnia N, Isaacs A, de Bakker PI, Dorr M, Newton-Cheh C, Nolte IM, van der Harst P, Muller M, Eijgelsheim M, Alonso A, Hicks AA, Padmanabhan S, Hayward C, Smith AV, Polasek O, Giovannone S, Fu J, Magnani JW, Marciante KD, Pfeufer A, Gharib SA, Teumer A, Li M, Bis JC, Rivadeneira F, Aspelund T, Kottgen A, Johnson T, Rice K, Sie MP, Wang YA, Klopp N, Fuchsberger C, Wild SH, Mateo Leach I, Estrada K, Volker U, Wright AF, Asselbergs FW, Qu J, Chakravarti A, Sinner MF, Kors JA, Petersmann A, Harris TB, Soliman EZ, Munroe PB, Psaty BM, Oostra BA, Cupples LA, Perz S, de Boer RA, Uitterlinden AG, Volzke H, Spector TD, Liu FY, Boerwinkle E, Dominiczak AF, Rotter JI, van Herpen G, Levy D, Wichmann HE, van Gilst WH, Witteman JC, Kroemer HK, Kao WH, Heckbert SR, Meitinger T, Hofman A, Campbell H, Folsom AR, van Veldhuisen DJ, Schwienbacher C, O’Donnell CJ, Volpato CB, Caulfield MJ, Connell JM, Launer L, Lu X, Franke L, Fehrmann RS, te Meerman G, Groen HJ, Weersma RK, van den Berg LH, Wijmenga C, Ophoff RA, Navis G, Rudan I, Snieder H, Wilson JF, Pramstaller PP, Siscovick DS, Wang TJ, Gudnason V, van Duijn CM, Felix SB, Fishman GI, Jamshidi Y, Stricker BH, Samani NJ, Kaab S, Arking DE. Common variants in 22 loci are associated with qrs duration and cardiac ventricular conduction. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1068–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murabito JM, Pencina MJ, Nam BH, D’Agostino RB Sr., Wang TJ, Lloyd-Jones D, Wilson PW, O’Donnell CJ. Sibling cardiovascular disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in middle-aged adults. JAMA. 2005;294:3117–3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundboll J, Adelborg K, Munch T, Froslev T, Sorensen HT, Botker HE, Schmidt M. Positive predictive value of cardiovascular diagnoses in the danish national patient registry: A validation study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.