Abstract

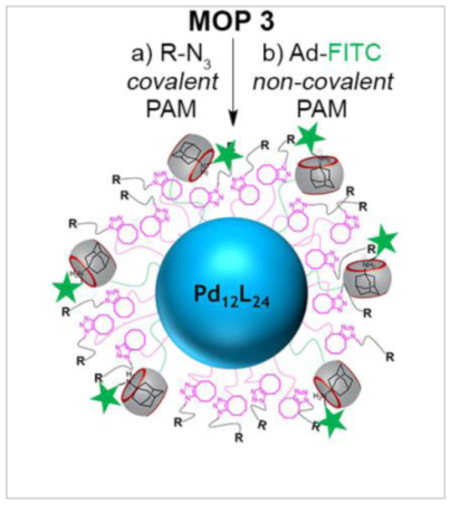

Mixed self-assembly of ligands 1 and 2, PXDA (3), and Pd(NO3)2 afforded metal organic polyhedra (MOP 1 – MOP 3) which bear 24 covalently attached CB[7] and cyclooctyne moieties. Post assembly modification (PAM) of MOP 3 by covalent strain promoted alkyne azide click reaction provided MOP 4R bearing covalently attached functionality (PEG, sulfonate, biotin, c-RGD, fluorescein and cyanine). Orthogonal CB[7] guest mediated non-covalent PAM of MOP 4R with Ad-FITC afforded MOP 5RGD Ad-FITC and MOP 5biotin0020Ad-FITC. Flow cytometry analysis of the uptake of MOP 5RGD Ad-FITC toward U87 cells demonstrated improved uptake relative to control MOP lacking c-RGD ligands. These results suggest a broad applicability of orthogonally functionalizable (covalent and non-covalent) MOPs in targeted drug delivery and imaging applications.

Keywords: Metal Organic Polyhedron, Cucurbit[n]uril, SPAAC, Post Assembly Modification, Cellular Targeting

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Metal organic polyhedra (MOPs) have emerged as an outstanding scaffold to prepare novel assemblies for materials and biomedical applications due to their defined size, shape, and multivalency.[1–3] For example, MOPs feature prominently in supramolecular catalysis, chemical sensing, transmembrane channels, theranostics, storage, hydrogels, and are considered for antibody-drug conjugates.[2, 4–14] Functionalization of MOPs is an essential step toward expanding their structural and functional complexity. Unfortunately, the co-self-assembly of mixed MOPs from collections of complex ligands is a daunting task that is often unsuccessful. For this reason, scientists in the metal-organic framework[15, 16] and, more recently, the MOP field have employed post−assembly modification (PAM)[17, 18] as a strategy to increase MOP functionality while preserving the potentially labile (e.g. toward metal catalysts or harsh reaction conditions) supramolecular frameworks.[1, 2, 19, 20] To date, only a handful examples of the PAM of MOPs have been reported.[21–27] For example, Stang and co-workers[23] first demonstrated the use of the strain promoted alkyne-azide click (SPAAC)[17, 23, 28] reaction to functionalize preformed self−assembled metallacycles. Nitschke and coworkers[21, 22] demonstrated the tetrazine−based inverse electron−demand Diels Alder reaction to perform the PAM of iron based cages. Although MOPs based on inert metal−ligand (Pt−N and Cu−O)[23, 24, 27] and labile but chelating metal−ligand (Fe-bpy type)[29, 30] interactions have been shown to withstand various PAM reactions, the covalent PAM of Fujita-type MOPs involving dynamic metal−ligand interactions (e.g. Pd−N) has not been so far explored.[31–33] We envisioned that the simultaneous orthogonal covalent SPAAC and non-covalent host-guest functionalization of MOPs would be a particularly powerful route to obtain complex MOP architectures. As the host component we decided to use cucurbit[n]uril (CB[n]) containers[34–37] because of their tight host-guest complexation,[36] biocompatibility, and their successful incorporation in relevant chemical and biomedical applications.[38–47]

For example, pioneering work by Stoddart, Zink and Yang demonstrated that the excellent recognition properties of CB[n] can be integrated with nanoparticles (e.g. mesoporous silica) for materials and biomedical applications.[48, 49] Joining a small number of reports on the theranostic applications of MOPs,[50–52] we recently reported that CB[n]−functionalized Fujita−type cubooctahedral MOPs can be used to deliver a doxorubicin prodrug and nile red dye to HeLa Cells.[7, 8] We describe herein the dual (covalent and non-covalent) PAM of a Fujita-type cubooctahedral MOP (Pd12L24) using covalent SPAAC and non-covalent CB[7] host-guest interactions to tailor a MOP for biomedical application by incorporating both targeting ligands and dyes. We refer to this dual PAM as the “click-and-clack” approach.1 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example where both covalent and non-covalent PAM has been simultaneously demonstrated.

Results and Discussion

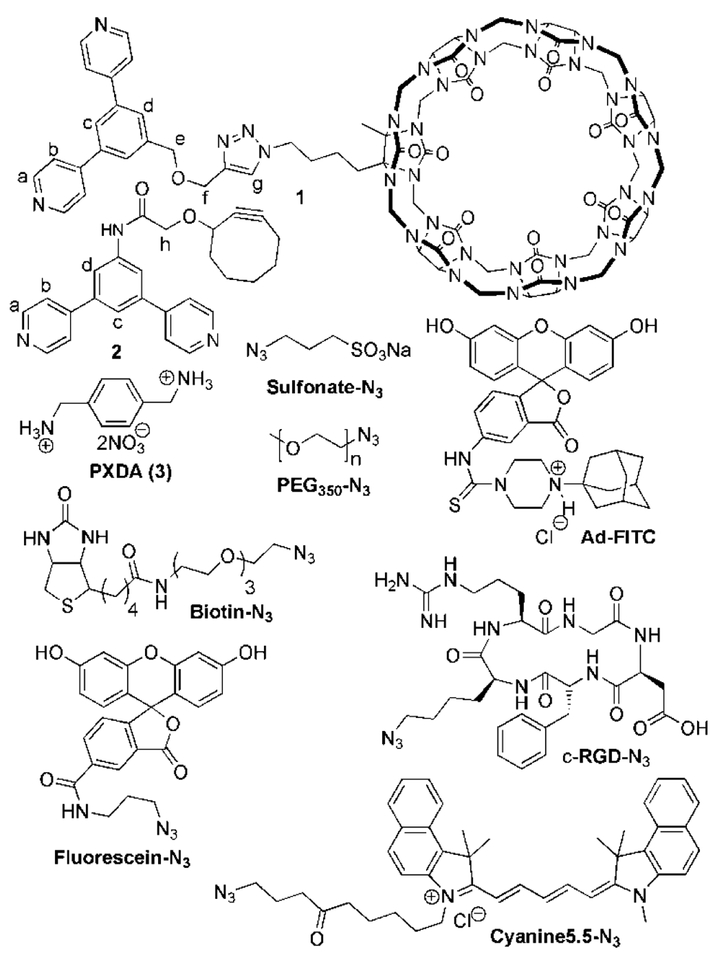

To implement the click-and-clack approach to perform PAM of the surface of a Fujita-type Pd12L24 MOP required the availability of cyclooctyne and CB[7]−functionalized (bis)pyridine derivatives. As the CB[7]−functionalized (bis)pyridine ligand we selected compound 1[8] (Chart 1). Cyclooctyne functionalized bispyridine ligand 2 was synthesized by the carbodiimide-promoted amide formation reaction between 3,5-bis(4-pyridyl)aniline[7] and cyclooctyne carboxylic acid[53] in 40% yield as described in the Supporting Information (SI).

Chart 1.

Molecular structures of compounds used in this study.

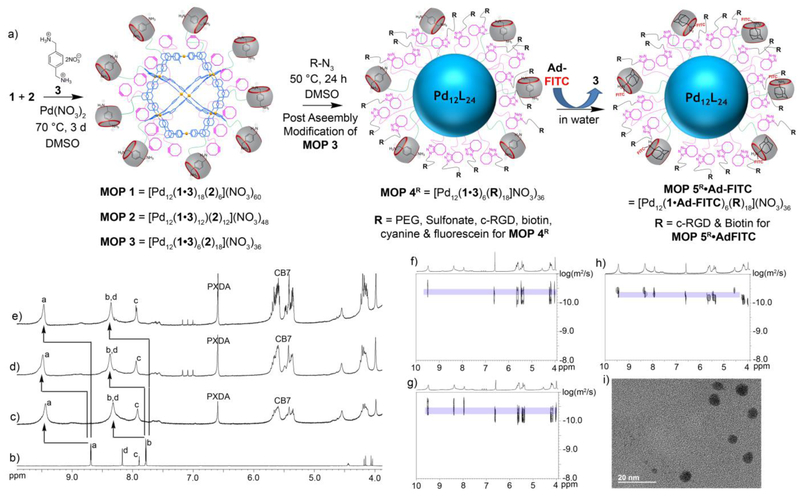

With the required (bis)pyridine ligands in hand (1 and 2) we turned our attention their co-self-assembly with Pd(NO3)2 to afford CB[7] and cyclooctyne functionalized MOPs. Experimentally, we found that heating Pd(NO3)2 with a mixture of 1, 2, and guest 3 in DMSO at 70 °C for 3 d afforded MOP 1 – MOP 3 (Figure 1). Guest 3 is included during the self-assembly process to preoccupy the cavity and portals of CB[7] and thereby prevent the sequestration of Pd2+ by CB[7]. The MOPs were characterized by 1H NMR and diffusion ordered spectroscopy (DOSY). A single set of broadened 1H NMR resonances were observed for the pyridyl protons (Ha and Hb) of ligands 1 and 2 components of MOP 1 – MOP 3 reflecting the statistical distribution of ligands throughout the structure and the slower tumbling motion of large cages on 1H NMR time scale (Figure 1b–e).[54] The 1H NMR spectra of MOP 1 – MOP 3 exhibits the typical downfield shifting of the pyridyl protons (Ha: 9.47 ppm; Hb = 8.36 ppm for MOP 1; see SI for MOP 2 and MOP 3) upon self-assembly relative to free 1 and 2 (Figure 1). Based on the relative integration of the Ha resonance of 1 and 2 versus that for the downfield CB[7] protons of 2 in the 1H NMR spectra of MOP1 – MOP3 we find that the stoichiometry of the CB[7] and cyclooctyne building blocks used in the self-assembly (6:18, 12:12, 18:6) are directly translated into the stoichiometric ratios observed for MOP 1 – MOP 3, respectively (Figure S10, S12 & S14). The hydrodynamic diameter of MOP 1 – MOP 3 can be determined by DOSY NMR (Figure 1f – 1h). The diffusion coefficients of MOP 1 – MOP 3 measured by DOSY in DMSO at 298 K were D = 3.12 × 10−11 m2/s, D = 3.54 × 10−11 m2/s & D = 5.01 × 10−11 m2/s, respectively. Using the Stokes−Einstein equation allows us to translate the measured diffusion coefficients into hydrodynamic diameters (MOP 1: 7.0 nm, MOP 2: 6.2 nm, MOP 3: 4.4 nm) as shown in the SI (Table S1).[55] As the number of CB[7] moieties is reduced from 18 to 12 to 6, the effective size of the MOP is significantly reduced. We ascribe this effect mainly to the lower number of massive CB[7] units (MW = 1162, diameter = 16.0 Å)[56] on the surface of MOPs and potentially also to intermolecular hydrophobic interaction[7] between the outer surface of CB[7] and the CB[7] moieties or aromatic scaffold of other MOP molecules. To further confirm the size and shape of the MOPs, we performed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) after deposition of a DMSO solution of the MOPs on a carbon-coated Cu grid. Both the size (MOP 1, d ≈ 6.5–7.0 nm; MOP 2, d ≈ 5.5–6.5 nm) and spherical shape of individual MOP assemblies can be seen clearly in the TEM images (Figure 1i and S33–34), and support the sizes estimated from DOSY NMR (vide supra).

Figure 1.

a) Co-assembly of ligand 1 and 2 afforded MOP 1 – MOP 3 in DMSO. Dual post−assembly modification (PAM) of MOP 3 has been demonstrated. Covalent PAM of MOP 3 by SPAAC with various functional azides (R-N3) gave MOP 4R. Non-covalent PAM of MOP 4R (for R = c-RGD & biotin) with adamantane-FITC (Ad-FITC) gave MOP 5R•Ad-FITC. 1H NMR spectra recorded (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) for: b) compound 2, c) MOP 3, d) MOP 2, and e) MOP 1. DOSY NMR recorded (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) for: f) MOP 1, g) MOP 2 and h) MOP 3. i) Transmission electron microscopy image of MOP 1.

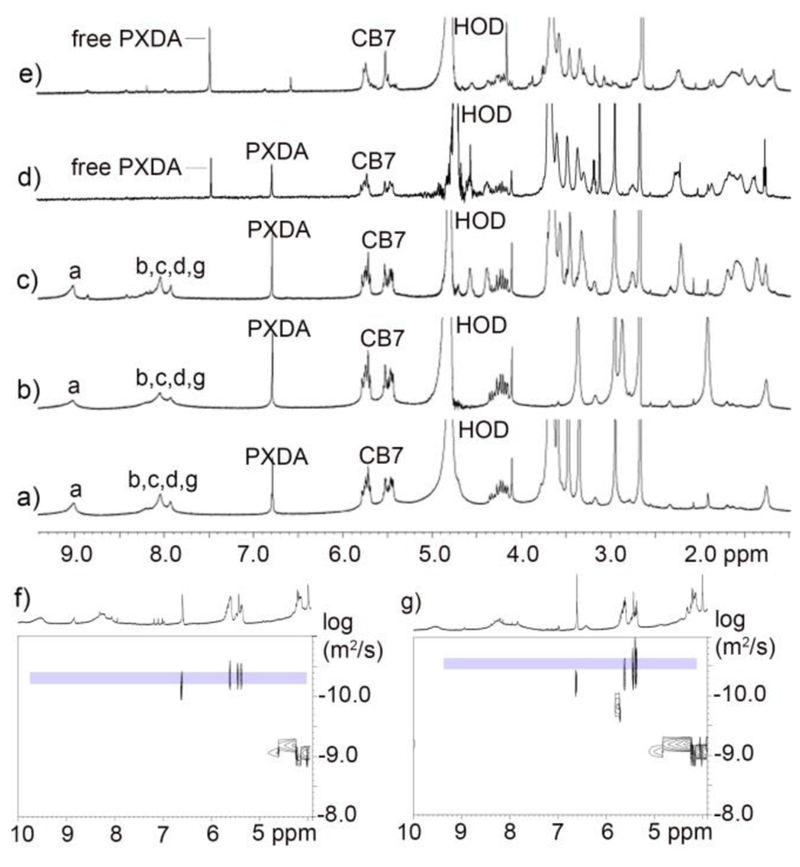

After the successful self-assembly of MOPs containing a plurality of CB[7] and cyclooctyne units as a common intermediate for PAM, we proceeded to investigate their stability under and ability to participate in a click-and-clack functionalization process. We choose MOP 3 as the model compound for these PAM investigations. First, we allowed MOP 3 to react with various functionalized azides (R-N3, Chart 1) by the SPAAC reaction. For example, MOP 3 could be transformed into MOP 4biotin by reaction with 18 equiv. of Biotin-N3 in DMSO at 50 °C for 24 hours (Figure 1a). The 1H NMR spectrum of MOP 4biotin clearly shows the downfield shifted Ha (9.56 ppm) resonance that is diagnostic for cubooctahedral Pd12L24 MOPs (Figure S23) which confirms the stability of the cage under the reaction conditions. Moreover, DOSY NMR shows that MOP 4biotin diffuses more slowly (D = 3.55 × 10−11 m2/s (Figure 2) than the MOP 3 starting material and therefore has a larger hydrodynamic diameter (d = 6.2 nm) than MOP 3 (d = 4.4 nm) as expected due to the long tetraethylene glycol biotin units.[57] The SPAAC reaction was also monitored by FT-IR spectroscopy. Although the cyclooctyne triple bond stretch of MOP 3 was not visible, the azide stretching frequency of Biotin-N3 (2097 cm−1) could be monitored during the reaction of MOP 3 with 18 equiv. Biotin-N3 at 50 °C. We observed the complete loss of the 2097 cm−1 stretching frequency (Figure 3 & S38) which indicates smooth conversion to MOP 4Biotin. To test the stability of MOP 4biotin in aqueous solution we dialyzed the DMSO solution against D2O for 24 h followed by 1H and DOSY NMR characterization. Once again, the 1H NMR clearly shows the diagnostic downfield shifting of the pyridyl Ha (9.02 ppm) resonances within cubooctahedral MOP 4biotin in water (Figure 2) which establishes the aqueous stability of the MOP. The relative integrals for the PXDA resonance at 6.79 ppm, the CB[7] resonances at 5.76–5.44 ppm, and those for the biotin methine protons at 4.57 and 4.38 ppm confirms the expected stoichiometry (1:2:3, 6:18:6) in MOP 4biotin assembly (Figure S25). D2O solutions of MOP 4biotin were stable over a period of 2 months as monitored by 1H NMR. DOSY NMR confirms the size of MOP 4biotin as 6.1 nm in D2O (Figure S26) in excellent agreement with the corresponding diameter in DMSO (Table S1).

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectra recorded (600 MHz, D2O, RT) for: a) MOP 4PEG, b) MOP 4sulfonate, c) MOP 4biotin, d) a mixture of MOP 4biotin and 3 equiv. of Ad-FITC, e) a mixture of MOP 4biotin and 6 equiv. of Ad-FITC. DOSY NMR recorded (600 MHz, DMSO, 298 K) for: f) MOP 4sulfo and g) MOP 4biotin.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra recorded for (a) MOP 3, (b) mixture of MOP 3 and 18 equiv. of biotin-N3, (c) Mixture of MOP 3 and 18 equiv. of biotin-N3 after heating at 50°C for 24 h.

Next, we sought to demonstrate the scope of the SPAAC covalent PAM of MOP 3 with azides. First, we selected two fluorescent dyes (Fluorescein-N3, Cyanine5.5-N3) that can be used for in vitro or in vivo imaging. Separately, MOP 3 was reacted with 18 equiv. of Fluorescein-N3 or Cyanine5.5-N3 by SPAAC in DMSO at 50 °C for 24h to deliver MOP 4Fluor and MOP 4cyan quantitatively (Figure 1a). The 1H NMR data of the products shows the retention of the downfield shifted pyridine Ha protons (9.50 ppm) which are characteristic of intact MOPs and the presence of resonances arising from the dyes (Figure S28 and S29). Next, we demonstrated PEGylation since this modification is well known to improve aqueous solubility and decrease the opsonisation of nanoparticles which increases blood circulation times and improves the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution.[58] Accordingly, MOP 3 was reacted with 18 equiv. of PEG350-azide at 50 °C in DMSO to afford MOP 4PEG (Figure 1a) quantitatively. The sample was characterized by 1H and DOSY NMR and displayed the characteristic resonances for intact MOP and covalently attached PEG350 units (Figure S17 and S18). After dialysis against D2O, the stability of MOP 4PEG in water was verified by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 2a). The relative integrals for the PXDA resonance at 6.79 ppm, the CB[7] resonances at 5.77–5.44 ppm, and those for the PEG protons at 3.54 ppm confirms the expected stoichiometry (1:2:3, 6:18:6). Subsequently, we sought to conjugate MOP 3 with Sulfonate-N3 in order to modulate the overall charge of the MOP since it is known that surface charge can dictate the cellular uptake pathway of nanoparticles.[59] Analogously, MOP 3 underwent SPAAC with 18 equiv. Sulfonate-N3 to smoothly deliver MOP 4Sulfonate (Figure 1a). MOP 4Sulfonate was characterized by 1H (Figure 2b) and DOSY NMR (Figure 2f); it has excellent stability in water as verified by 1H NMR over 2 months. Finally, we sought to functionalize MOP 3 with RGD cyclic peptide binding epitopes that would allow receptor mediated uptake by cells expressing integrin receptors on their surface.[60] SPAAC reaction of MOP 3 with c-RGD-N3 delivered MOP 4RGD (Figure 1a) which was characterized by 1H NMR (Figure S27). The ability of MOP 3 to undergo smooth PAM by SPAAC with a variety of functionalized azides should open up new avenues for their use in biomedical applications.

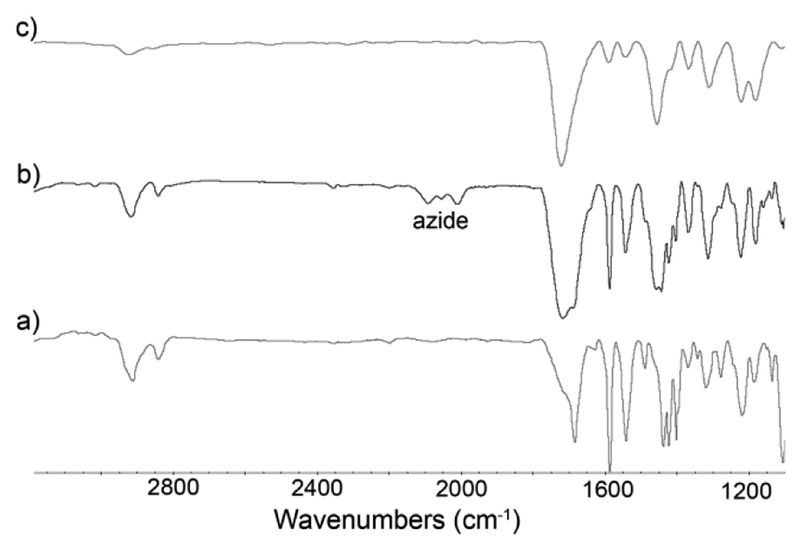

After covalent PAM, we verified the ability of the MOPs toward non-covalent PAM by CB[7]•guest complexation. Guest 3 is known to bind to unfunctionalized CB[7] with Ka = 1.84 × 109 M−1.[61] To displace 3, we selected fluorescent adamantane derivative Ad-FITC because adamantane ammonium ions are known to bind tightly to CB[7] with Ka > 1012 M−1. Accordingly, treatment of an aqueous solution of MOP 4biotin sample with 6 equiv. of Ad-FITC (1 per CB[7] unit) gave MOP 5biotin•Ad-FITC (Figure 1a). The guest exchange process was monitored by 1H NMR titration (Figure 2c–e & S30) which clearly shows the gradual disappearance of the resonance for bound 3 at 6.79 ppm upon addition of Ad-FITC and appearance of sharp resonance at 7.5 ppm corresponding to free 3. Although the resonances corresponding to adamantane bound to CB[7] were obscured by the broad peak already present at 0.9−1.7 ppm, the integral for the 0.9–1.7 ppm region increased from MOP 4biotin (Figure S25) to MOP 5biotin•Ad-FITC (Figure S31) due to the adamantane peaks underneath those broad peaks. The pyridine protons of MOP 5biotin•Ad-FITC are broadened into the baseline due to the slower tumbling motion of the larger MOP 5biotin•Ad-FITC assembly. Similarly, addition of Ad-FITC to MOP 4RGD gave MOP 5RGD•Ad-FITC. This study exemplifies the dual click-and-clack PAM of Pd12L24−type MOPs and also establishes the excellent aqueous and organic stability of the MOPs post functionalization.

The click-and-clack modified MOPs offered us the opportunity to expand the chemical functionalities of MOPs for various applications. For example, in MOP 5RGD•Ad-FITC and MOP 5biotin•Ad-FITC, the MOP is equipped with both targeting ligand (RGD or biotin) and a fluorophore (Ad-FITC) dye that enabled us to study targeted delivery of the MOP by flow cytometry. Accordingly we tested the targeting ability of MOP 5RGD•Ad-FITC by incubating with U87 glioblastoma cells – which express c-RGD binding integrin receptors on their surface – at 4 °C for 30 min in culture media (Figure 4). The cells were washed three times with PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry. Figure 3 shows plots of fluorescence intensity versus cell count for untreated U87 cells (red curve) and U87 cells treated with MOP 5RGD•Ad-FITC (0.5 μM, green curve). The U87 cells treated with MOP 5RGD•Ad-FITC showed a significant increase in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) compared to background cellular auto-fluorescence of the untreated cells. As an important negative control, we synthesized FITC−labelled MOP 3•Ad-FITC6 (Figure S32) that does not bear c-RGD targeting ligands by non-covalent functionalization of MOP 3. Figure 4 shows that control MOP 3•Ad-FITC6 (blue curve) gave a smaller increase in MFI than MOP 5RGD•Ad-FITC confirming the role of c-RGD in cell binding. The small increase in MFI of control MOP (MOP 3•Ad-FITC6) relative to background cellular MFI suggests the presence of non-specific binding of the cationic MOPs toward the U87 cells. The observed enhancement in MFI for c-RGD functionalized MOPs sets the stage for their use for targeted drug delivery and imaging applications.

Figure 4.

Cellular targeting with MOP 5RGD•Ad-FITC. Cell targeting experiment was performed using flow cytometry. MOP 5RGD•Ad-FITC (0.5 μM) bound to U87 cells is shown in green trace. MOPs that were unmodified on the exterior by RGD i.e. MOP 6 (0.5 μM) is shown in blue trace. Background autofluorescence is shown in red trace.

Conclusions

In summary, we have synthesized Fujita-type M12L24 metal organic polyhedra (MOP 1 – MOP 3) that feature covalently attached reactive cyclooctyne and complexable CB[7] units on their external surfaces. The stoichiometric ratio of reactive cyclooctyne and complexable CB[7] units can be monitored after the self-assembly process by extensive 1H NMR, DOSY NMR, and TEM characterization. MOP 3 underwent covalent click PAM by SPAAC reaction with a variety of ligands (Biotin-N3, c-RGD-N3, PEG350-N3, Sulfonate-N3, Cyanine5.5-N3, FITC-N3) relevant for biomedical application to yield MOP 4R. Non-covalent clack PAM of MOP 4R was achieved by addition of tighter binding CB[7] ligands (e.g. Ad-FITC). Flow cytometry results demonstrated that MOP 5RGD•Ad-FITC results in enhanced U87 cellular uptake relative to controls. As a whole, the work demonstrates the click-and-clack approach to functionalize Fujita-type M12L24 metal organic polyhedra by orthogonal SPAAC covalent and CB[7]•guest mediated non-covalent PAM. Given the high importance of MOPs as well as metal organic frameworks and metal nanoparticles in numerous chemical, materials, and biomedical applications, we expect the click-and-clack approach will deliver increased control over their chemical constitution and stimuli responsive functions.

Experimental Section

General Procedure

Starting materials were purchased from commercial suppliers and were used without further purification. Melting points were measured on a Meltemp apparatus in open capillary tubes and are uncorrected. IR spectra were measured on a Thermo Nicolet NEXUS 670 FT/IR spectrometer by attenuated total reflectance (ATR) and are reported in cm−1. NMR spectra were measured on commercial spectrometers operating at 400, 500, or 600 MHz for 1H and 100, 125 or 150 MHz for 13C using deuterated water (D2O), deuterated chloroform (CDCl3), or deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) as solvent. Chemical shifts (δ) are referenced relative to the residual resonances for HOD (4.79 ppm), CHCl3 (7.26 ppm for 1H, 77.16 ppm for 13C), and DMSO-d6 (2.50 ppm for 1H, 39.51 ppm for 13C). Mass spectrometry was performed using a JEOL AccuTOF electrospray instrument. TEM was performed on a JEOL JEM 2100. Molecular modeling (MMFF) was performed using Spartan ‘08 on a personal computer.

Experimental Procedure

Synthesis of compound 2:

A solution of 2-(cyclooct-2-yn-1-yloxy)acetic acid (5) (137 mg, 0.75 mmol) and 3,5-di(pyridin-4-yl)aniline (6) (146 mg, 0.59 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20.0 mL) was treated with 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (430 mg, 2.24 mmol) and DMAP (92 mg, 0.75 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h under N2 and then the solvent was removed under vacuum. The crude product was loaded onto a silica gel column and eluted using 2% MeOH in CHCl3 to give 2 as a colorless oil. The colorless oil was treated with diethyl ether (2.0 mL) and then sonicated which gave a white solid. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation and dried under vacuum to give 2 as a white solid (97 mg, 40%). Mp. 120–121 °C. IR (ATR, cm−1): 2918 (m), 2847 (m), 1689 (s), 1592 (s), 1546 (s), 1495 (w), 1442 (s), 1428 (s), 1407 (s). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 9.98 (s, 1H), 8.69 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 4H), 8.17 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.89 (br s, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 4H), 4.44 (s, 1 H), 4.16 (d, J = 14.9 Hz, 1H), 4.05 (d, J = 14.9 Hz, 1H), 2.27–1.40 (m, 10H) ppm. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 169.0, 150.8, 147.2, 140.3, 139.2, 122.1, 121.5, 119.6, 101.7, 92.8, 73.0, 68.7, 42.2, 34.5, 29.7, 26.5, 20.5 ppm. HR-MS: m/z 412.1978 ([M+H]+, calcd. for [C26H25N3O2+H]+, 412.2025).

Synthesis of MOP 1:

Compound 1 (3.5 mg, 2.22 μmol) was dissolved in DMSO-d6 (400 μL) followed by the addition of 3 (0.583 mg, 2.22 μmol). The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 2 h, and then treated with 2 (0.304 mg, 0.74 μmol), and Pd(NO3)2 (0.788 mg, 2.96 μmol) and the resulting solution was stirred at 70 °C for 3d. The formation of MOP 1 = [Pd12(1•3)18(2)6](NO3)60 was confirmed by 1H NMR. MOP 1 was isolated by evaporating DMSO solution under high vacuum. Mp > 300 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 9.47 (s, 96H), 8.36 (br s, 120H), 7.95 (br s, 66H), 6.59 (s, 72H), 5.69–5.35 (m, 468H), 4.55 (br s, 6H), 4.24–4.13 (m, 252H), 3.99 (s, 72H), 3.15–3.05 (m, 36H), 2.08 (br s), 1.90–1.62 (m), 1.27–1.08 (m) ppm. DOSY NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): D = 3.12 × 10−11 m2/s.

Synthesis of MOP 2:

Compound 1 (4.90 mg, 3.11 μmol) was dissolved in DMSO-d6 (500 μL) followed by the addition of 3 (0.815 mg, 3.11 μmol). The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 2 h and then compound 2 (1.28 mg, 3.11 μmol), and Pd(NO3)2 (1.66 mg, 6.22 μmol) were added and the resulting solution was stirred at 70 °C for 2 d. The quantitative formation of MOP 2 was observed by 1H NMR and DOSY NMR. Mp > 300 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 9.48 (s, 96H), 8.37 (br s, 126H), 7.94 (br s, 54H), 6.60 (s, 48H), 5.70–5.36 (m, 312H), 4.56 (br s, 12H), 4.24–4.17 (m, 168H), 3.99 (s, 48H), 3.14–3.07 (m, 24H), 1.90–1.49 (m), 1.23–1.16 (m) ppm. DOSY NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): D = 3.54 × 10−11 m2/s.

Synthesis of MOP 3:

Compound 1 (4.5 mg, 2.86 μmol) was dissolved in DMSO-d6 (500 μL) followed by addition of 3 (0.75 mg, 2.86 μmol). The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 2 h and then 2 (3.53 mg, 8.58 μmol), and Pd(NO3)2 (3.05 mg, 11.4 μmol) were added and the resulting solution was stirred at 70 °C for 24 h. The quantitative formation of MOP 3 was observed by 1H NMR and DOSY NMR. The DMSO solution of MOP 3 was transferred to a dialysis tube (MWCO 3500) and the solution was dialyzed for 2 d against D2O (every 6 h D2O (10 mL) was replaced fresh D2O). MOP 3 was isolated by evaporating the aqueous solution. Mp > 300 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 9.43 (s, 96H), 8.32 (br s, 110H), 7.92 (br s, 66H), 6.59 (s, 24H), 5.69–5.34 (m, 156H), 4.54 (br s, 18H), 4.22–4.16 (m, 84H), 3.98 (s, 24H), 3.14–3.06 (m, 12H), 1.89–1.59 (m), 1.23–1.15 (m) ppm. DOSY NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K) D = 5.01 × 10−11 m2/s.

General Procedure for covalent Post Assembly Modification (PAM) of MOP 3 using the Strain Promoted Alkyne Azide Click (SPAAC) Reaction:

A solution of MOP 3 (3.5 mg) in DMSO-d6 (400 μL) was treated with 18 equiv. of the desired R-N3 (R = PEG350, sulfonate, c−RGD, biotin, cyanine 5.5 & fluorescein compounds) dissolved in DMSO-d6 (150 μL). The resulting mixture was heated at 50 °C for 24 h to give MOP 4R. The solution was characterized by 1H and DOSY NMR. The DMSO solution of MOP 4R was transferred to a dialysis tube (MWCO 3500) and the solution was dialyzed for 24 h against D2O (every 4 h D2O (10 mL) was replaced by fresh D2O). The aqueous solution of MOP 4R was characterized by 1H NMR.

Procedure for noncovalent Post Assembly Modification (PAM) of MOP 4biotin using CB[7] host-guest exchange reactions.

A solution of MOP 4biotin (20 μM in D2O) sample was titrated with Ad-FITC (500 μM in D2O) dissolved in D2O. After each aliquot was added the sample was mixed thoroughly and a 1H NMR spectrum was recorded. The titration was stopped after addition of 6 equiv. of Ad-FITC to MOP 4biotin sample.

In vitro study: Targeted Uptake Experiments.

5 × 105 cells/200 μL of U87 cells were plated in a 96-well plate (Corning) and treated with MOP 5RGD•Ad-FITC and MOP 6 at a concentration of 0.5 μM for 30 mins at 4 °C. Cells were washed 3 times with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS; Cellgro) and collected for analysis by flow cytometry. Each experiment was performed with two technical replicates and was repeated three times and one representative outcome is shown.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institutes of Health (CA168365) for financial support. B.V. thanks the University of Maryland for a Millard and Lee Alexander fellowship and a Department of Education GAANN fellowship (P200A120241).

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/MS-number.

Click is defined as “a slight, sharp sound” whereas Clack is defined as “to make a quick sharp sound” Webster’s College Dictionary (Ed.: R. B. Costello), Random House, New York, 1991.

References

- [1].Cook TR, Stang PJ, ‘Recent Developments in the Preparation and Chemistry of Metallacycles and Metallacages via Coordination’, Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 7001–7045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Harris K, Fujita D, Fujita M, ‘Giant hollow MnL2n spherical complexes: structure, functionalisation and applications’, Chem. Commun 2013, 49, 6703–6712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].McConnell AJ, Wood CS, Neelakandan PP, Nitschke JR, ‘Stimuli-Responsive Metal–Ligand Assemblies’, Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 7729–7793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brown CJ, Toste FD, Bergman RG, Raymond KN, ‘Supramolecular Catalysis in Metal–Ligand Cluster Hosts’, Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 3012–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Neelakandan PP, Jimenez A, Nitschke JR, ‘Fluorophore incorporation allows nanomolar guest sensing and white-light emission in M4L6 cage complexes’, Chem. Sci 2014, 5, 908–915. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Roy B, Ghosh AK, Srivastava S, D’Silva P, Mukherjee PS, ‘A Pd8 Tetrafacial Molecular Barrel as Carrier for Water Insoluble Fluorophore’, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 11916–11919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Samanta SK, Moncelet D, Briken V, Isaacs L, ‘Metal–Organic Polyhedron Capped with Cucurbit[8]uril Delivers Doxorubicin to Cancer Cells’, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 14488–14496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Samanta SK, Quigley J, Vinciguerra B, Briken V, Isaacs L, ‘Cucurbit[7]uril Enables Multi-Stimuli-Responsive Release from the Self-Assembled Hydrophobic Phase of a Metal Organic Polyhedron’, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 9066–9074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mal P, Breiner B, Rissanen K, Nitschke JR, ‘White Phosphorus Is Air-Stable Within a Self-Assembled Tetrahedral Capsule’, Science 2009, 324, 1697–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhukhovitskiy AV, Zhong M, Keeler EG, Michaelis VK, Sun JEP, Hore MJA, Pochan DJ, Griffin RG, Willard AP, Johnson JA, ‘Highly branched and loop-rich gels via formation of metal–organic cages linked by polymers’, Nat. Chem. 2015, 8, 33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang YA-O, Gu Y, Keeler EG, Park JV, Griffin RG, Johnson JA-O, ‘Star PolyMOCs with Diverse Structures, Dynamics, and Functions by Three-Component Assembly’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 188–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jung M, Kim H, Baek K, Kim K, ‘Synthetic Ion Channel Based on Metal–Organic Polyhedra’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 5755–5757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Casini A, Woods B, Wenzel M, ‘The Promise of Self-Assembled 3D Supramolecular Coordination Complexes for Biomedical Applications’, Inorg. Chem 2017, 56, 14715–14729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gramage-Doria R, Hessels J, Leenders SHAM, Troeppner O, Duerr M, Ivanovic-Burmazovic I, Reek JNH, ‘Gold(I) Catalysis at Extreme Concentrations Inside Self-Assembled Nanospheres’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 13380–13384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cohen SM, ‘The Postsynthetic Renaissance in Porous Solids’, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 2855–2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cohen SM, ‘Postsynthetic Methods for the Functionalization of Metal–Organic Frameworks’, Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 970–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Roberts DA, Pilgrim BS, Nitschke JR, ‘Covalent post-assembly modification in metallosupramolecular chemistry’, Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 626–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Meyer CD, Joiner CS, Stoddart JF, ‘Template-directed synthesis employing reversible imine bond formation’, Chem. Soc. Rev 2007, 36, 1705–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Williams Alan F, Piguet C, Bernardinelli G, ‘A Self-Assembling Triple-Helical Co Complex : Synthesis and Structure’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2003, 30, 1490–1492. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ma Z, Han S, Hopson R, Wei Y, Moulton B, ‘Two-step postsynthetic modifications of a dinuclear Zn(II) coordination compound: Investigating the stability of the coordination chromophore’, Inorg. Chim. Acta 2012, 388, 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pilgrim BS, Roberts DA, Lohr TG, Ronson TK, Nitschke JR, ‘Signal transduction in a covalent post-assembly modification cascade’, Nat. Chem 2017, 9, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Roberts DA, Pilgrim BS, Cooper JD, Ronson TK, Zarra S, Nitschke JR, ‘Post-assembly Modification of Tetrazine-Edged FeII4L6 Tetrahedra’, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 10068–10071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chakrabarty R, Stang PJ, ‘Post-assembly Functionalization of Organoplatinum(II) Metallacycles via Copper-free Click Chemistry’, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 14738–14741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhao D, Tan S, Yuan D, Lu W, Rezenom Yohannes H, Jiang H, Wang LQ, Zhou HC, ‘Surface Functionalization of Porous Coordination Nanocages Via Click Chemistry and Their Application in Drug Delivery’, Adv. Mater 2010, 23, 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang M, Lan W-J, Zheng Y-R, Cook TR, White HS, Stang PJ, ‘Post-Self-Assembly Covalent Chemistry of Discrete Multicomponent Metallosupramolecular Hexagonal Prisms’, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 10752–10755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Brega V, Zeller M, He Y, Peter Lu H, Klosterman JK, ‘Multi-responsive metal-organic lantern cages in solution’, Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 5077–5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zheng W, Chen L-J, Yang G, Sun B, Wang X, Jiang B, Yin G-Q, Zhang L, Li X, Liu M, Chen G, Yang H-B, ‘Construction of Smart Supramolecular Polymeric Hydrogels Cross-linked by Discrete Organoplatinum(II) Metallacycles via Post-Assembly Polymerization’, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 4927–4937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sletten Ellen M , Carolyn R. Bertozzi ’Bioorthogonal Chemistry: Fishing for Selectivity in a Sea of Functionality’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 6974–6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Young MC, Johnson AM, Hooley RJ, ‘Self-promoted post-synthetic modification of metal-ligand M2L3 mesocates’, Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 1378–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Holloway LR, Bogie PM, Lyon Y, Julian RR, Hooley RJ, ‘Stereoselective Postassembly CH Oxidation of Self-Assembled Metal–Ligand Cage Complexes’, Inorg. Chem 2017, 56, 11435–11442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Han M, Luo Y, Damaschke B, Gomez L, Ribas X, Jose A, Peretzki P, Seibt M, Clever GH, ‘Light-controlled interconversion between a self-assembled triangle and a rhombicuboctahedral sphere’, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 445–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Samanta D, Chowdhury A, Mukherjee PS, ‘Covalent Postassembly Modification and Water Adsorption of Pd3 Self-Assembled Trinuclear Barrels’, Inorg. Chem 2016, 55, 1562–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Uchida J, Yoshio M, Sato S, Yokoyama H, Fujita M, Kato T, ‘Self-Assembly of Giant Spherical Liquid-Crystalline Complexes and Formation of Nanostructured Dynamic Gels that Exhibit Self-Healing Properties’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 14085–14089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Isaacs L, ‘Stimuli Responsive Systems Constructed Using Cucurbit[n]uril-Type Molecular Containers’, Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 2052–2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Barrow SJ, Kasera S, Rowland MJ, del Barrio J, Scherman OA, ‘Cucurbituril-Based Molecular Recognition’, Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 12320–12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Shetty D, Khedkar JK, Park KM, Kim K, ‘Can we beat the biotin-avidin pair?: cucurbit[7]uril-based ultrahigh affinity host-guest complexes and their applications’, Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44, 8747–8761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Assaf KI, Nau WM, ‘Cucurbiturils: from synthesis to high-affinity binding and catalysis’, Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44, 394–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ganapati S, Isaacs L, ‘Acyclic Cucurbit[n]uril-type Receptors: Preparation, Molecular Recognition Properties and Biological Applications’, Isr. J. Chem 2017, 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Walker S, Oun R, McInnes Fiona J, Wheate Nial J, ‘The Potential of Cucurbit[n]urils in Drug Delivery’, Isr. J. Chem 2011, 51, 616–624. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Oun R, Floriano RS, Isaacs L, Rowan EG, Wheate NJ, ‘The ex vivo neurotoxic, myotoxic and cardiotoxic activity of cucurbituril-based macrocyclic drug delivery vehicles’, Toxicology Research (Cambridge, United Kingdom) 2014, 3, 447–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Uzunova VD, Cullinane C, Brix K, Nau WM, Day AI, ‘Toxicity of cucurbit[7]uril and cucurbit[8]uril: an exploratory in vitro and in vivo study’, Org. Biomol. Chem 2010, 8, 2037–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hettiarachchi G, Nguyen D, Wu J, Lucas D, Ma D, Isaacs L, Briken V, ‘Toxicology and Drug Delivery by Cucurbit[n]uril Type Molecular Containers’, PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e10514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jung H, Park JS, Yeom J, Selvapalam N, Park KM, Oh K, Yang J-A, Park KH, Hahn SK, Kim K, ‘3D Tissue Engineered Supramolecular Hydrogels for Controlled Chondrogenesis of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells’, Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 707–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Yeom J, Kim Su J, Jung H, Namkoong H, Yang J, Hwang Byung W, Oh K, Kim K, Sung Young C, Hahn Sei K, ‘Supramolecular Hydrogels for Long-Term Bioengineered Stem Cell Therapy, Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2014, 4, 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kim S, Yun G, Khan S, Kim J, Murray J, Lee YM, Kim WJ, Lee G, Kim S, Shetty D, Kang JH, Kim JY, Park KM, Kim K, ‘Cucurbit[6]uril-based polymer nanocapsules as a non-covalent and modular bioimaging platform for multimodal in vivo imaging’, Materials Horizons 2017, 4, 450–455. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Murray J, Sim J, Oh K, Sung G, Lee A, Shrinidhi A, Thirunarayanan A, Shetty D, Kim K, ‘Enrichment of Specifically Labeled Proteins by an Immobilized Host Molecule’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 129, 2435–2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Park KM, Murray J, Kim K, ‘Ultrastable Artificial Binding Pairs as a Supramolecular Latching System: A Next Generation Chemical Tool for Proteomics’, Acc. Chem. Res 2017, 50, 644–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ambrogio MW, Thomas CR, Zhao Y-L, Zink JI, Stoddart JF, ‘Mechanized Silica Nanoparticles: A New Frontier in Theranostic Nanomedicine’, Acc. Chem. Res 2011, 44, 903–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wu Z, Song N, Menz R, Pingali B, Yang Y-W, Zheng Y, ‘Nanoparticles functionalized with supramolecular host–guest systems for nanomedicine and healthcare’, Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 1493–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Schmitt F, Freudenreich J, Barry NPE, Juillerat-Jeanneret L, Süss-Fink G, Therrien B, ‘Organometallic Cages as Vehicles for Intracellular Release of Photosensitizers’, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 754–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Zheng Y-R, Suntharalingam K, Johnstone TC, Lippard SJ, ‘Encapsulation of Pt(iv) prodrugs within a Pt(ii) cage for drug delivery’, Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 1189–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zhang M, Li S, Yan X, Zhou Z, Saha ML, Wang Y-C, Stang PJ, ‘Fluorescent metallacycle-cored polymers via covalent linkage and their use as contrast agents for cell imaging’, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113, 11100–11105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Bernardin A, Cazet A, Guyon L, Delannoy P, Vinet F, Bonnaffé D, Texier I, ‘Copper-Free Click Chemistry for Highly Luminescent Quantum Dot Conjugates: Application to in Vivo Metabolic Imaging’, Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 21, 583–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tominaga M, Suzuki K, Kawano M, Kusukawa T, Ozeki T, Sakamoto S, Yamaguchi K, Fujita M, ‘Finite, Spherical Coordination Networks that Self-Organize from 36 Small Components’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2004, 43, 5621–5625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Cohen Y, Avram L, Frish L, ‘Diffusion NMR Spectroscopy in Supramolecular and Combinatorial Chemistry: An Old Parameter—New Insights’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 44, 520–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lee JW, Samal S, Selvapalam N, Kim H-J, Kim K, ‘Cucurbituril Homologues and Derivatives: New Opportunities in Supramolecular Chemistry’, Acc. Chem. Res 2003, 36, 621–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sato S, Ikemi M, Kikuchi T, Matsumura S, Shiba K, Fujita M, ‘Bridging Adhesion of a Protein onto an Inorganic Surface Using Self-Assembled Dual-Functionalized Spheres’, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 12890–12896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Fleischer CC, Payne CK, ‘Nanoparticle–Cell Interactions: Molecular Structure of the Protein Corona and Cellular Outcomes’, Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 2651–2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wang J, Byrne James D, Napier Mary E, DeSimone Joseph M, ‘More Effective Nanomedicines through Particle Design’, Small 2011, 7, 1919–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Danhier F, Le Breton A, Préat V, ‘RGD-Based Strategies To Target Alpha(v) Beta(3) Integrin in Cancer Therapy and Diagnosis’, Mol. Pharmaceutics 2012, 9, 2961–2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Liu S, Ruspic C, Mukhopadhyay P, Chakrabarti S, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L, ‘The Cucurbit[n]uril Family: Prime Components for Self-Sorting Systems’, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 15959–15967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.