Abstract

Introduction

Health numeracy helps individuals understand risk information, but limited data exist concerning numeracy’s role in reactions to varying types of health warning labels (HWLs) for cigarettes.

Methods

A nationally representative online panel of adult current smokers received two exposures (1 week apart) to nine HWLs with either text-only or pictorial images with identical mandated text. Following the second exposure, participants (n = 594) rated their beliefs in smoking myths (eg, health-promoting behaviors can undo the risks of smoking) and how much the warnings made them want to quit smoking. Generalized estimating equation regression examined the relation of objective health numeracy and its interaction with HWL type to smoking-myth beliefs and quit-related reactions.

Results

Health numeracy was not significantly associated with smoking-myth beliefs; the interaction with HWL type was also nonsignificant. Adult smokers with lower health numeracy had higher quit-related reactions than those with higher numeracy following exposure to HWLs. The type of HWL significantly modified numeracy’s associations with quit-related reactions; no significant association existed between text-only HWLs and quit-related reactions, whereas among those who viewed the pictorial warnings, lower numeracy was associated with greater quit-related reactions (β = −.23; p < .001).

Conclusions

Lower as compared to higher health numeracy was significantly associated with higher quit-related reactions to HWLs and especially with pictorial HWLs. Health numeracy and HWL type were not associated with the endorsement of smoking myths. The role of health numeracy in effectively communicating risks to smokers warrants thoughtful consideration in the development of tobacco HWLs.

Implications

Health numeracy plays an important role in an individual’s ability to understand and respond to health risks. Smokers with lower health numeracy had greater quit-related reactions to pictorial health warnings than those who viewed text-only warning labels. Development and testing of health warning labels should consider health numeracy to most effectively communicate risk to US smokers.

Introduction

Health numeracy assists individuals to understand uncertain health outcomes and risk information, to make better health decisions, and to complete health tasks that require numeracy skills.1 Numerical information can only be useful for decision making if an individual sufficiently understands and acts upon their meaning. Reyna et al.2 note that “low numeracy distorts perceptions of risks and benefits of screening, reduces medication compliance, impedes access to treatments, and impairs risk communication (limiting prevention efforts among the most vulnerable).” Indeed, a 2011 systematic review concluded that lower health numeracy is associated with poorer health outcomes.3 In the United States, higher health numeracy has been associated with increased odds of smoking cessation among smokers, where every 1-point increase in numeracy skills was associated with a 24% increased odds of quitting smoking.4 Having lower skills is also associated with increased beliefs in various myths (eg, less educated smokers and smoking myths;1,5 less numerate patients and cancer myths).6 These relationships suggest that smokers with lower numeracy may accept smoking myths more too. Previous studies of smoking myths have shown a relation with intentions to quit smoking.7

The less numerate often find health information too difficult and abstract,8 but evidence-based communications may reduce these numeracy differences. Health risk messages should convey risk magnitude clearly and, ideally, alter perceived susceptibility to the condition to motivate risk-reduction behaviors in the target population. By definition, health warning labels (HWLs) on cigarettes are intended to serve this purpose. In 2009, the U.S. Congress mandated nine health warning messages and pictorial imagery on cigarette packages and advertisements, but legal issues have blocked their use.9 The proposed health warning text does not explicitly include numerical information. Nonetheless, HWLs may require numeracy skills for consumers to understand the probabilistic meaning of health risk information such as “cigarettes cause fatal lung disease” to motivate cessation. Visual displays, such as pictorial imagery, have shown promise within numeracy research to bridge gaps in risk comprehension between those with higher and lower numeracy skills.10 Health numeracy among regular smokers has not been extensively studied prospectively, but cross-sectional comparisons of smokers to never smokers indicate smokers have lower numeracy (4.7 vs. 5.8; on a scale of 0–8).7

Despite robust examinations of HWL attributes, little is known about how health numeracy contributes to reactions to HWLs. In this study, we evaluated how health numeracy relates to incorrect beliefs about the effects of early or limited smoking (referred to here as smoking myths) and a measure of each warning’s ability to stimulate quit reactions was assessed as a measure of warning effectiveness. Two hypotheses were tested:

Hypothesis 1: Individuals with lower versus higher numeracy would report reduced acceptance of smoking myths when shown a pictorial compared to text HWL.

Hypothesis 2: Individuals with lower versus higher numeracy would have higher quit-related reactions when shown a pictorial compared to text HWL.

Methods

Sample

A US nationally representative sample of adult online panel participants was interviewed weekly for a total of 3 weeks, referred to here as waves 1 through 3. Wave 2 data were included in the present analytic sample (n = 594) to examine reactions to warnings after a second exposure; wave 3 data focused on recall and other effects and were not germane to the present study hypotheses. Online surveys were administered in English and Spanish by the GfK Government & Academic Group (http://www.gfk.com/en-us/products-a-z/us/government-academic-north-america/). The GfK KnowledgePanel covers 97% of US households. Respondents were selected using random probability address-based sampling; computers and internet services were provided to respondents as needed to ensure fuller representation of the American public. Final data were weighted by gender, age, race, ethnicity, education, and smoking status according to the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2013.

Eligibility criteria included adults aged 18 years or older who were current (past month) smokers or recent quitters and reported having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. At wave 1, a total of 2542 adult participants were screened for study eligibility and 1380 completed the screener (54.3% screener completion rate); 746 of those eligible and successfully screened completed the baseline survey (29.3% completion rate). The retention rate in wave 2 was high (79.6%), with a final sample of n = 594. Participants received a cash equivalent of $5 for wave 1 and $10 for wave 2; median survey completion time was 15 and 17 minutes, respectively, by wave. Surveys were pretested prior to the main study that occurred between April and May 2015. The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. This experimental study was not preregistered.

Measures

The intervention in this study was type of HWL as participants were randomized to view one of two conditions: A text-only (control) or pictorial warning condition using seven of the pictorial warnings proposed by US Food and Drug Administration along with two that replaced images proposed by US Food and Drug Administration (intervention). Warning images were shown on screen independent of any product packaging. The two replacements were selected to be more memorable based on pretesting (paired with the “smoking is addictive” and “quitting now reduces the risk of smoking” messages). Both conditions used all nine of the originally mandated health warning messages.

Two outcome variables were used in the present analyses. First, quit-related reaction to warnings was operationalized by a single item asked following exposure to each of the nine HWLs: “How much does this warning make you want to stop smoking?” Responses were measured with a 7-point rating scale from 1 = not at all to 7 = completely, and the mean rating taken across all HWLs represents this article’s quit-related reaction measure. The second outcome of smoking-myth beliefs was operationalized using two items related to lower smoking risk perceptions in past research:5 “There is usually no risk to the person at all for the first few years,” and “Although smoking may eventually harm this person’s health, there is really no harm to him or her from smoking the very next cigarette” measured on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) and averaged for a smoking-myth rating (range 1–7; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84).

The primary independent variables were experimental condition (text-only or pictorial HWLs) and an objective numeracy score (range 0–8; modified from Weller et al.,4 a more difficult scale than used previously with smokers7). The numeracy test included eight items to measure the ability to manipulate and use numerical information, such as “Suppose you have a normal, two-sided coin. If you flip it 60 times, how many times would you expect heads to turn up?” Covariates included race (white or nonwhite), gender (male or female), and education (less than high school graduate or some college or greater).

Data Analysis

Summary and descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample; chi-square and t tests were used to evaluate differences between study conditions on participant characteristics (p < .05). Generalized estimating equations were used to test the stated hypotheses regarding the relationship of study condition and numeracy with the outcomes of quit intention and smoking myths. Bivariate associations between demographic factors were conducted for each outcome independently to evaluate potential confounders. The final regression models used post-stratification weights to achieve a nationally representative sample, and all analyses used the dichotomized covariates of race, gender, and education. To decrease the risk of a Type II error when looking for statistical interactions, statistical significance was taken to be p < .05 for these hypotheses. Analyses were conducted using SAS, v. 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Demographic characteristics of adult smokers who completed waves 1 and 2 of data collection (n = 594) are shown in Table 1 using sampling weights and stratified by study condition; there were no significant differences in demographics by study condition. The mean and median objective numeracy scores were both 3.0 (out of 8 possible); 45.5% of the sample scored below 3.0.

Table 1.

Demographics of Study Participants in an Online Panel Study of Health Warning Labels

| Demographics | Total sample (n = 594) |

Text-only warning condition (n = 291) |

Pictorial warning condition (n = 303) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 43.8% | 39.5% | 48.0% |

| Age (yrs) | |||

| 18–24 | 29.8% | 31.6% | 28.0% |

| 25–30 | 26.8% | 26.8% | 26.7% |

| 31–40 | 22.3% | 21.7% | 22.8% |

| 41–59 | 21.2% | 19.9% | 22.5% |

| Educational attainment | |||

| Less than high school | 20.6% | 21.2% | 20.0% |

| High school graduate | 34.9% | 31.4% | 38.3% |

| Some college | 32.3% | 34.1% | 30.4% |

| Bachelor or higher | 12.3% | 13.2% | 11.3% |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 67.1% | 62.2% | 72.1% |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 12.2% | 15.1% | 9.3% |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 5.2% | 4.4% | 6.0% |

| Hispanic | 13.3% | 16.1% | 10.6% |

| 2+ races, non-Hispanic | 2.1% | 2.3% | 2.0% |

| Mean no. of cigarettes per day (SD) | 12.4 (9.0) | 11.6 (8.5) | 13.3 (9.5) |

| Mean objective numeracy score, 0–8 (SD) | 2.9 (1.9) | 2.8 (2.0) | 3.0 (1.9) |

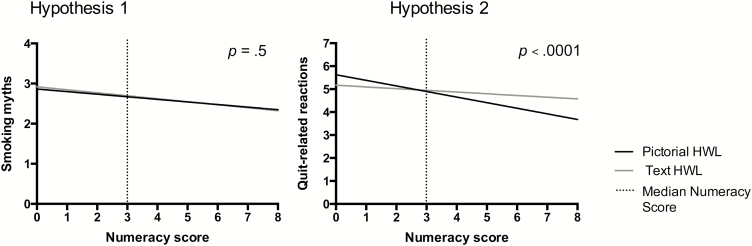

Figure 1 displays the regression results testing study hypotheses after adjustment for gender, race, and educational attainment. No significant association existed between numeracy and the endorsement of smoking myths (p = .2). The two-way interaction between the type of warning label and numeracy also was not associated with the endorsement of smoking myths (p = .5). The relationship between objective numeracy and quit-related reaction was highly significant; lower numeracy was associated with greater quit-related reaction (p < .001). Individuals with lower versus higher numeracy had particularly higher quit-related reactions when shown a pictorial compared to text HWL (interaction p < .0001). Among smokers who viewed a text warning, no significant association was found between numeracy and quit-related reactions (β = −.05; p = .45), whereas among those who viewed the pictorial warnings, lower numeracy was associated with greater quit-related reaction (β = −.23; p = <.0001).

Figure 1.

Interactions between objective numeracy and health warning label type for smoking myths and quit-related reactions among adult smokers (n = 594). All results are adjusted for gender, race, and educational attainment.

Discussion

Health numeracy modifies reactions to risk communications intended to inform health decision making.11–15 In our nationally representative sample of adult smokers, participants with lower objective numeracy scores reported greater quit-related reaction to pictorial HWLs than to text-only HWLs. This article represents the first examination of the role of objective numeracy in reactions to HWLs.

Pictorial HWL are recommended for promoting health over text-only HWLs;16 graphic images may also impact smokers with lower health literacy or education.17 Our findings on reaction differences by numeracy level may be particularly important to further promotion of cessation efforts, as greater health numeracy has been associated with increased odds of smoking cessation among smokers in the United States where cigarette packages have text-only HWLs; every 1-point increase in numeracy skills was associated with a 24% increased odds of quitting smoking.7 This successful trend may mean that the remaining pool of smokers has become increasingly less health numerate and/or literate,7 pointing toward pictorial HWLs as a reasonable next step toward supporting cessation efforts. In light of the inverse relationship between objective numeracy and quit-related reactions and the literature highlighting the relation of numeracy with health outcomes, we suggest that consideration of how numeracy influences smokers’ responses to health warnings is warranted for any revised HWL. The warnings proposed for use in the United States focus little on smoking myths. The failure to observe effects of numeracy on smoking myths in this study could imply that numeracy has greater effects on immediate reactions to warnings than on more distant implications of them. Future research on warnings for cigarettes could explore ways to correct such myths, which have been shown to undermine intentions to quit smoking.

There are some important limitations in this study. Our definition of current smoking included individuals who did not smoke in the past 30 days (n = 42); in a post hoc sensitivity analysis for the primary outcomes, no meaningful difference resulted when these individuals were excluded (data not shown). We used a nationally representative online sample methodology, which has been deemed to be more accurate than using nonprobability samples18 and adds to the strength of the present results. This study used two exposures to HWLs, which improves on single-exposure studies but does not replicate a naturalistic exposure to risk communication messages. Quit-related reactions were higher among less numerate smokers in our sample. Although these results may appear counter to the finding that more numerate smokers quit more,7 our quit-related reactions are likely more similar to a risk perception than a quit intention or behavior, and the less numerate tend to perceive more risks than the highly numerate across a variety of domains.2

Although insufficient evidence exists of a direct relationship between health numeracy and uptake of smoking,3 HWLs and other tobacco communication strategies for reducing uptake and increasing cessation should be tested and developed with health literacy and numeracy skills in mind. The proportion of smokers with inadequate numeracy is not precisely known, but current smokers are more likely to have lower numeracy, lower educational attainment, and other social disadvantages as compared to never smokers;7,19 thus, the estimated benefits of enhancing quit-related reactions among less numerate smokers may produce greater population-level benefits. As numeracy cannot be reliably inferred or assumed based on educational attainment or other observable characteristics, more consideration of health numeracy in risk communications with clinical and community-dwelling populations is warranted.11,20

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute and Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products (P50CA180908 and R01CA157824). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the FDA.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Finney Rutten LJ, Augustson EM, Moser RP, Beckjord EB, Hesse BW. Smoking knowledge and behavior in the United States: sociodemographic, smoking status, and geographic patterns. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(10):1559–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reyna VF, Nelson WL, Han PK, Dieckmann NF. How numeracy influences risk comprehension and medical decision making. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(6):943–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weller JA, Dieckmann NF, Tusler M, Mertz CK, Burns WJ, Peters E. Development and testing of an abbreviated numeracy scale: a Rasch analysis approach. J Behav Decis Mak. 2013;26(2):198–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dillard AJ, McCaul KD, Klein WM. Unrealistic optimism in smokers: implications for smoking myth endorsement and self-protective motivation. J Health Commun. 2006;11 (suppl 1):93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith SG, Kobayashi LC, Wolf MS, Raine R, Wardle J, von Wagner C. The associations between objective numeracy and colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes and defensive processing in a deprived community sample. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(8):1665–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martin LT, Haas A, Schonlau M, et al. Which literacy skills are associated with smoking?J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(2):189–192. doi: 10.1136/jech.2011.136341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schapira MM, Fletcher KE, Gilligan MA, et al. A framework for health numeracy: how patients use quantitative skills in health care. J Health Commun. 2008;13(5):501–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization. Guidelines for Implementation of Article 11 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (Packaging and Labelling of Tobacco Products) 2008. http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/article_11.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2018.

- 10. Krosnick JA, Malhotra N, Mo CH, et al. Perceptions of health risks of cigarette smoking: a new measure reveals widespread misunderstanding. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Mayman G, Fagerlin A, Anderson BL, Schulkin J. Patient Numeracy: What Do Patients Need to Recognize, Think, or Do with Health Numbers?In: Anderson BL, Schulkin J, eds. Numerical Reasoning in Judgments and Decision Making about Health. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014:80–104. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gardner PH, McMillan B, Raynor DK, Woolf E, Knapp P. The effect of numeracy on the comprehension of information about medicines in users of a patient information website. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(3):398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Keller C, Siegrist M. Effect of risk communication formats on risk perception depending on numeracy. Med Decis Making. 2009;29(4):483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lipkus IM, Peters E. Understanding the role of numeracy in health: proposed theoretical framework and practical insights. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(6):1065–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peters E, Dieckmann N, Dixon A, Hibbard JH, Mertz CK. Less is more in presenting quality information to consumers. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(2):169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Noar SM, Francis DB, Bridges C, Sontag JM, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. The impact of strengthening cigarette pack warnings: systematic review of longitudinal observational studies. Soc Sci Med. 2016;164:118–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thrasher JF, Carpenter MJ, Andrews JO, et al. Cigarette warning label policy alternatives and smoking-related health disparities. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(6):590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baker R, Blumberg SJ, Brick JM, et al. AAPOR report on online panels. Public Opin Q. 2010;74(4):711–781. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ryan H, Trosclair A, Gfroerer J. Adult current smoking: differences in definitions and prevalence estimates—NHIS and NSDUH, 2008. J Env Public Heal. 2012;2012. doi:10.1155/2012/918368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peters E, Hibbard J, Slovic P, Dieckmann N. Numeracy skill and the communication, comprehension, and use of risk-benefit information. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(3):741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]