Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the most common causes of neurological damage in young people. It was previously reported that dietary restriction, by either intermittent fasting (IF) or daily caloric restriction (CR), could protect neurons against dysfunction and degeneration in animal models of stroke and Parkinson’s disease. Recently, several studies have shown that the protein Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) plays a significant role in the induced neuroprotection following dietary restriction. In the present study, we found a significant reduction of SIRT1 levels in the cortex and hippocampus in a mouse model of mild weight-drop closed head TBI. This reduction was prevented in mice maintained on IF (alternate day fasting) and CR initiated after the head trauma. Hippocampus-dependent learning and memory (measured using a novel object recognition test) was impaired 30 days post-injury in mice fed ad libitum, but not in mice in the IF and CR groups. These results suggest a clinical potential for IF and/or CR as an intervention to reduce brain damage and improve functional outcome in TBI patients.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Cognitive deficits, Axonal regeneration, Intermittent fasting, Caloric restriction

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) occurs when an object or external force hits the head. The main causes of TBI are road accidents, falls, assaults, and sport injuries (Holm et al. 2005). Among the population under the age of 50, TBI is the most common neurological disorder (McAllister 2011; Slemmer et al. 2008; Zohar et al. 2003). The effects of TBI can be temporary or permanent and can cause physiological, cognitive, motor, and behavioral deficits, which range on the spectrum between total lack of symptoms to severe deficits and death (De Kruijk et al. 2001; Gao et al. 2003). Despite the prevalence of TBI, there is still no complete understanding of the destructive mechanisms in the injured brain at the molecular and cellular levels. In addition, mild TBI (mTBI), which accounts for over 80% of head injuries, is difficult to diagnose because routine tests, including imaging, fail to show changes in brain structure (De Kruijk et al. 2001; Tashlykov et al. 2009)

The pathophysiology of TBI can be divided into primary and secondary injury mechanisms. The primary injury occurs directly due to the physical injury and may result in intracranial or extracranial hemorrhage due to damage to the blood vessels (Greve and Zink 2009). Moreover, damage to the brain tissue and the brain blood barrier (BBB) may occur (Rubovitch et al. 2011; Tashlykov et al. 2007). Following these events, the secondary injury occurs within a period of hours to weeks after the primary injury (Greve and Zink 2009) and involves a series of inflammatory reactions. Mostly, the secondary injury will be more severe and complex than the primary and will include anatomical, cellular, molecular, and behavioral changes. When the neuronal cells fail to overcome these damages, secondary damage will cause cell death, either apoptotic or necrotic death (Rachmany et al. 2013). Since it takes time for secondary damage to occur, a “window of opportunity” is created during which a pharmacological or nutritional treatment can be administered.

Dietary restriction (DR) is a well-known reliable mechanism shown to slow down the onset of age-associated pathologies and increase the lifespan of many organisms (Mattson et al. 2018; Speakman and Mitchell 2011). DR may be defined as the reduction in food intake without causing any malnutrition. Two types of DR regimens have been employed in animal and human studies. Intermittent fasting (IF) typically involves alternate day fasting, fasting 2 days each week, or daily time-restricted fasting (Mattson et al. 2017). Another form of DR is the restriction of calories intake at a defined percentage of the overall intake or a gradually increasing restriction up to 60% of the regular diet (Speakman and Mitchell 2011).

Dietary restriction (DR) was found to be protective in reducing cognitive damage in animal models of the Alzheimer disease (AD) (Brownlow et al. 2014; Dhurandhar et al. 2013; Halagappa et al. 2007). Many studies show that there is a strong link between metabolic dysregulation and decreased brain function during aging. In humans, high blood glucose and excess of nutrients are a risk factor for cognitive decline and even AD in the elderly (Haan 2006). Studies conducted on rodents have shown that DR treatment reduces age-related learning and coordination abilities (Mattson et al. 2003; Rich et al. 2010). Several neuroprotective mechanisms have been suggested to be involved in the beneficial effects of IF and CR, including antioxidant effects, the formation of ketone bodies, anti-inflammatory effects, and increased neurotrophic factor activities. DR increases the expression of various neurodevelopmental factors, such as the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), the neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), and the glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) (Agarwal et al. 2005; Hunt et al. 2006; Lambert and Merry 2004; Rankin et al. 2006). Recently, several studies have shown that the protein Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) plays a significant role in the induced neuroprotection following DR (Ingram et al. 2007; Ran et al. 2015). In recent years, studies have demonstrated the important role of the Sirtuin family in the mechanism by which DR retards the aging processes (Guarente 2013). Sirtuins have also been described as proteins that play an important role in development, affecting the brain structure through axon elongation, neurite outgrowth, and dendritic branching (Li et al. 2013). In addition, sirtuins can determine the fate of the neurotransmitters in neurons (Prozorovski et al. 2008; Rafalski et al. 2013)

SIRT1, one of the major members of this family, has a role in the development of the hippocampus by its ability to activate Akt and inhibit GSK3. SIRT1 is involved in a variety of physiological processes such as genetic silencing, genome stability, and cell life extension (Martin et al. 2015; Pasinetti et al. 2015). Further studies have shown that the Sirtuin family is involved in the hypothalamus where it plays roles in regulation of the circadian cycle, endocrine pathways, and appetite (Chang and Guarente 2013; Cohen et al. 2009; Ramadori et al. 2011; Sasaki et al. 2010).

In the present study, we report that CR and IF, initiated after mTBI, ameliorated the cognitive deficits induced by the injury and sustained the levels of SIRT1 expression.

Experimental Procedures

Animal Studies

ICR male mice, ages 6–7 weeks, weighing 30–40 g, were purchased from Envigo RMS Israel. The Sackler Commission on Animal Experimentation approved the trial protocol 01–16-021 according to the Guidelines for Animal Experimentation of the National Institutes of Health (DHEW publication 23–85, revised, 1995). The mice were kept at room temperature at a light/dark cycle of 12 h, 4–5 mice in a standard plastic cage (32 × 21.5 × 12 cm3). Water was freely accessible and the cages bedding was sawdust which was replaced twice a week, in a similar way for all the cages. After the animals arrived at the laboratory, they were given 2–3 days of recovery from the transport and for acclimatization in the new location. Two days before the experiment, all the cages were transferred to the experimental room for the purpose of getting used to the new environment, and reducing anxiety. In addition, animals who took part in behavioral tests were not used for biochemical testing.

Induction of Head Injury in Mice

The head injury in this experiment was performed according to the closed-head weight-drop model. In this model, a fixed weight is released for a free fall according to a defined path. The weight and the height from which it is dropped determine the severity of the injury, and it can range from a mild level of injury to severe brain injury. In the present study, the mice were subjected to mild TBI (mTBI). In the pre-induction stage, the mice were anesthetized by inhaling isoflurane vapor for several minutes. At the time of induction, the mice were kept in such a way as to direct the injury from the frontal lateral direction on the right side of the mouse’s head, at an equal distance between the eye and the right ear. The mice were placed on a spongy surface that allows the movement of the head parallel to the injury plane at the time of the weight fall and thus mimics a head injury that occurs during a car accident. The head injury was induced by using the concussive head trauma device, which has been described previously in our lab (Milman et al. 2005; Zohar et al. 2003). The device is a hollow metal tube (with an internal diameter of 13 mm) that is placed vertically above the head of the mouse. A metal weight (30 g) is inserted into the metal pipe, which falls in a free fall of 80 cm. This model was chosen because it simulates traumatic head injuries such as road accidents or falls, as it imposes a diffuse and non-specific injury.

Intermittent Fasting

Immediately after the mTBI induction, mice of IF and mTBI groups were deprived of food for 24 h and were then maintained on an alternate day fasting regimen in which food was either provided or removed at 8:00 am every other day (repeating cycles of 24 h with no food followed by 24 h with food) for 30 days after mTBI. Water was provided without restriction. Mice in the control diet groups (control and mTBI) were fed “ad libitum” throughout the period.

Caloric Restriction

Immediately after the induction, mice of caloric restriction (CR) and mTBI + CR groups fed 90% of the calculated average food intake value (10% CR), followed by 1 week of 20% CR, 1 week of 30% CR, and then 2 weeks of 40% CR. Water was provided without restriction. Mice in the control diet groups (control and mTBI) were fed “ad libitum” throughout the period.

Novel Object Recognition

Novel object recognition (NOR) was performed 30 days post-mTBI. This test examines the visual memory of the animal based on the natural curiosity that exists in rodents for new objects. The testing arena is built in the shape of a square surface (60 cm × 60 cm) and has high walls (20 cm). The Novel object recognition test consists of three stages:

Adjustment stage: the mouse is placed in the empty arena for 5 min to learn the surface itself.

Learning stage (24 h after acclimatization): the mouse is inserted into the arena where two identical objects (A) are placed for 5 min to recognize them. We will define them as “old” objects.

The test stage (24 h after learning stage): the mouse is inserted into the arena where two objects are placed, one is known from the learning phase (A) and one is “new”(B), for 5 min.

Between one animal and the other, the surface and the objects were cleaned with ethanol to mask odors that the animals left behind.

The Aggelton index is calculated to assess the extent of learning and visual memory of animals according to the following formula:

A higher preference index indicates better learning. Animals who were present at the objects less than 10% of the total time of the test (i.e., less than 30 s next to the two objects together) were excluded from statistical calculations, since, when a mouse does not explore the objects at all, it is not possible to estimate its visual memory level.

Elevated Plus Maze Protocol

The elevated plus maze (EPM) test provides a measure of anxiety in rodents. This assessment relies on the natural anxiety-like behavior exhibited by rodents when placed in brightly lit open environments. The apparatus is in the shape of a plus formation (+), with arms extending from the center at 90° angles from each other. Opposite arms in the plus formation are identical, i.e., for the low open “unsafe” arms, the walls are 30 cm long × 5 cm wide × 1 cm high and the other two “safe” arms have high walls 30 cm long × 5 cm wide × 15 cm high; all arms have open tops. To induce additional stress to the animals, the maze is raised above floor level by 50 cm. The high “safe” and low “unsafe” arms are made of black and white acrylic glass, respectively. This assessment utilizes a single trial where animals are placed in the middle the EPM facing one of the open “safe” arms. The trial lasts for 5 min where the total time the mouse spends in all of the arms is recorded and used statistically to identify any treatment-dependent changes in fear-like behavior.

Western Blot

To assess SIRT1 levels in mouse brains, animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital and perfused transcardially with a PBS (pH 7.4) solution. Half of the brains were excised at 30th and half at 31st day post-TBI and frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at − 80 °C. Thereafter, brains were homogenized in 100 μL/400 μL of Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent, Pierce, supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Sigma-Aldrich( using a Teflon pestle homogenizer. Homogenates were centrifuged for 15 min at 4 °C at 14,000 rpm; then, the supernatant liquid was removed and stored at − 80 °C. Then, sample buffer was added to the sample and stored at − 20 °C. Prior to electrophoresis, the sample was heated to 90 °C for 3 min then 30 μL and then loaded on a gel (cat. 456–1094, Mini-PROTEAN TGX Gel 4–20%), and proteins were then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Trans-Blot Turbo, Bio-Red). The membrane was blocked by incubating in 5% BSA in TTBS for at least 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary mouse anti-SIRT1 antibody (diluted 1:500; ab10304; Abcam(and washings with TTBS. Membranes were then incubated at room temperature for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) and bound antibody detected using enhanced chemiluminescense with ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence assay) (Pierce Rockford, IL) by Fusion FX7 for 1 min. The densitometry analysis of the detected signal was made using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Membranes were stripped and incubated with anti-mouse α-tubulin antibody (diluted 1:10000; cat. sc-53030, Santa Cruz) then conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Jackson) to rectify the amount of protein. The quantification of every sample was determined by the proportion between SIRT1 and α-tubulin; then, the samples were normalized to the control group at the same membrane.

Mice whose brains were used in western blot were not tested by behavior studies.

Data Analysis

All values are presented as mean values ± standard error. Significance was calculated using the ANOVA (analysis of variance) tests for continuous variables. For post hoc comparisons, we used Fisher LSD post hoc tests. One-way ANOVA were performed in SPSS_20 and t tests were performed in Excel. Statistically significant differences between the averages will be marked by asterisk, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01.

Results

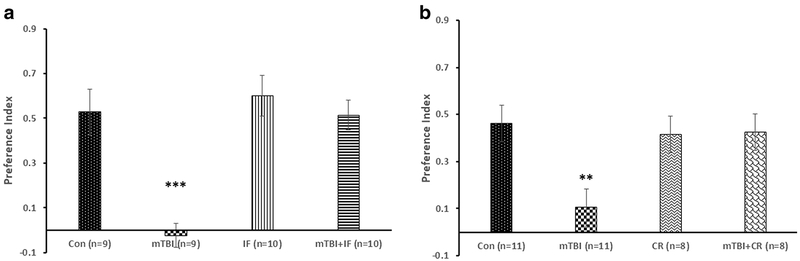

Dietary Restriction Ameliorates Cognitive Deficits in a Mouse Model of mTBI

The first set of experiments was aimed at assessing the effect of the two modes of DR (CR and IF) on the visual memory in mice 30 days after mTBI. In order to do so, we used the novel object recognition (NOR). Figure 1a shows that the preference index was significantly reduced in mTBI mice compared with control (from 0.528 ± 0.10 to − 0.023 ± 0.16, respectively; ***p < 0.001; n = 9). The IF diet (mTBI + IF) completely prevented this cognitive impairment in mTBI mice (0.514 ± 0.07; n = 10). In the CR study, mTBI significantly reduced the object preference index indicating cognitive impairment (from 0.462 ± 0.07 to 0.105 ± 0.0.05; **p < 0.01; n = 11). CR diet (mTBI + CR) prevented the cognitive impairment in mTBI mice (0.425 ± 0.08, n = 8, Fig. 1b). Neither IF nor CR had a significant effect on object recognition memory in uninjured control mice (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1.

DR ameliorates a cognitive deficit after mTBI. The behavioral tests were performed 30 days post-mTBI and/or DR. The recognition memory was assessed by the novel object recognition (NOR) test by calculating the relative time that the mice spent near a novel object compared with an old, familiar one (“preference index,” see “Novel Object Recognition”). Both intermittent fasting (IF, a) and caloric restriction (CR, b) significantly prevented the significant decrease of preference index in mTBI mice. One-way ANOVA revealed significant effect of group: a [F(3,34) = 12.302, ***p = 0.0001]; b [F(3,34) = 4.970, **p = 0.006]

The elevated plus maze (EPM) was performed to evaluate the anxiety-like behavior of the mice. We did not find any significant differences between the experimental groups (data not shown).

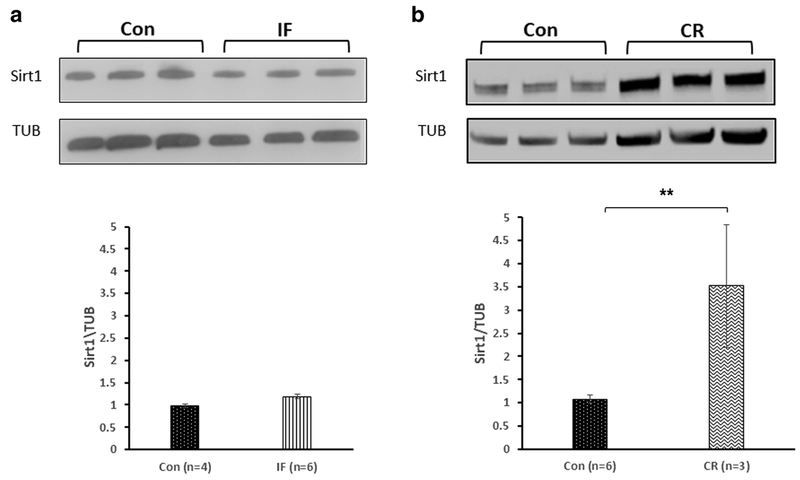

CR, but Not IF, Increases the Expression of SIRT1 in the Cerebral Cortex

IF did not alter the expression of SIRT1 in the cortex of mice compared with control mice fed ad libitum (0.979 ± 0.01 and 1.18 ± 0.08, respectively; Fig. 2a). CR, on the other hand, significantly increased SIRT1 levels in the cortex compared with control mice fed ad libitum (3.51 ± 1.32 and 1.08 ± 0.09, respectively; **p < 0.01; n = 3–6; Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

The effect of diet restriction on the expression of SIRT1 in the cortex of mice. a Intermittent fasting (IF) did not alter the expression of SIRT1 in the cortices of mice compared with untreated control mice. t test revealed no differences in expression SIRT1 between the Con to the IF diet (p = 0.28). b Calorie restriction (CR), on the other hand, significantly elevated SIRT1 levels in the cortex compared with the untreated control mice. t test revealed a significant elevation in expression SIRT1 in mice fed in CR (p = 0.007)

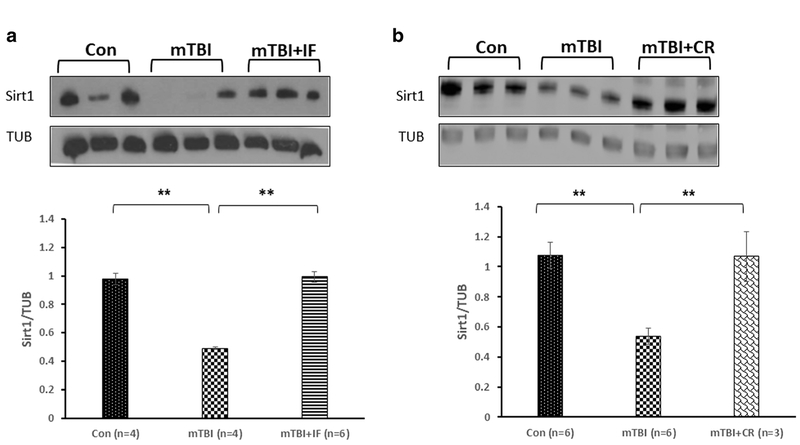

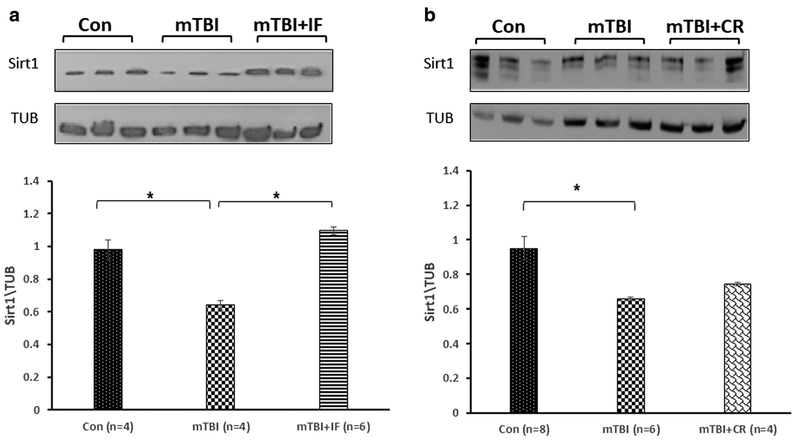

IF and CR Prevent the Reduction of SIRT1 Expression Following mTBI

Figure 3a shows that the levels of SIRT1 were significantly reduced 30 days post-injury in the cortex of mTBI mice compared with control (0.492 ± 0.01 and 0.979 ± 0.04, respectively, **p < 0.01; n = 4–6). In contrast, SIRT1 levels were not significantly reduced in the cortex of mice in the IF diet group (0.993 ± 0.01 **p < 0.01; n = 6;). Similarly, SIRT1 levels were not significantly reduced in the cortex of mice in the CR diet group (Fig. 3a) compared with mice in the ad libitum control mTBI group (1.068 ± 0.166 and 0.536 ± 0.05, respectively, **p < 0.01; n = 3–6).

Fig. 3.

The effect of diet restriction on SIRT1 expression in the cortex of mTBI mice. a The levels of SIRT1 were significantly reduced 30 days post-injury in the cortex of mTBI mice compared with control. IF diet prevented this reduction. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant elevation in expression SIRT1 in mTBI + IF. [F(2,11) = 12.335, **p = 0.002] values are mean ± SEM. b CR diet induced a similar protective effect, and the levels of SIRT1 in the cortices of the injured mice under CR were significantly higher compared with the injured mice. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant elevation in expression SIRT1 in mTBI + CR [F(2,13) = 11.080, **p = 0.002]. Tukey’s post hoc test values are mean ± SEM

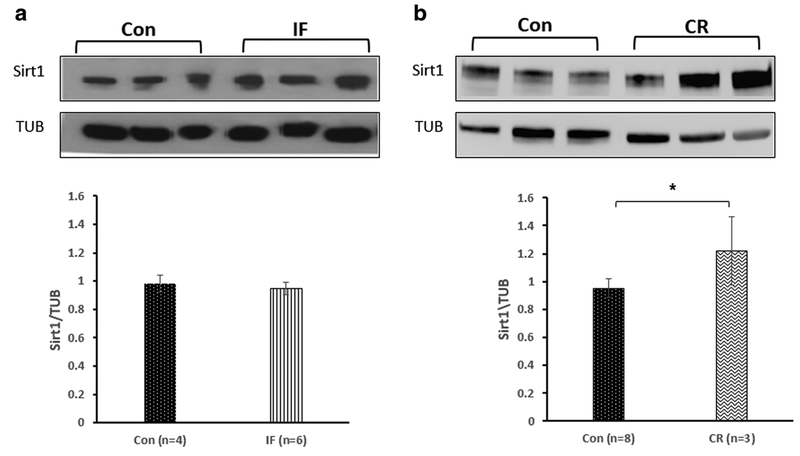

CR, but Not IF, Increases the Expression of SIRT1 in the Hippocampus

IF did not alter the expression of SIRT1 in the hippocampus compared with mice fed ad libitum (0.978 ± 0.07 and 0.95 ± 0.08, respectively; Fig. 4a). CR significantly elevated SIRT1 levels in the hippocampus compared with the untreated control mice (1.221 ± 0.24 and 0.951 ± 0.07, respectively; *p < 0.01; n = 3–8; Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

The effect of diet restriction on the expression of SIRT1 in the hippocampus of mice. a Intermittent fasting (IF) did not alter the expression of SIRT1 in the hippocampi of mice compared with untreated control mice. t test revealed no differences in expression SIRT1 between the Con to the IF diet (p =0.45). b Calorie restriction (CR), on the other hand, significantly elevated SIRT1 levels in the HP compared with the untreated control mice. t test revealed a significant elevation in expression SIRT1 in mice fed in CR (*p < 0.05)

IF, but Not CR, Prevents the mTBI-Induced Reduction of SIRT1 Levels in the Hippocampus

Figure 5a shows that the levels of SIRT1 were significantly reduced 30 days post-injury in the hippocampus of mTBI mice compared with control uninjured mice (0.638 ± 0.03 and 0.979 ± 0.06, respectively, *p < 0.05; n = 4–6). The IF diet prevented this reduction (1.097 ± 0.02, *p < 0.05; n = 6). CR did not prevent the mTBI-induced reduction in the level of SIRT1 in the hippocampus (Fig. 5b) (0.744 ± 0.01 and 0.657 ± 0.01, respectively, n.s; n = 4–6).

Fig. 5.

The effect of diet restriction on SIRT1 expression in the hippocampus of mTBI mice. a The levels of SIRT1 were significantly reduced 30 days post-injury in the cortex of mTBI mice compared with control. IF diet prevented this reduction. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant elevation in expression SIRT1 in mTBI + IF. [F(2,11) = 6.975, *p < 0.05] values are mean ± SEM. b CR diet induced a similar protective effect, and the levels of SIRT1 in the cortices of the injured mice under CR were significantly higher compared with the injured mice. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant elevation in expression SIRT1 in mTBI + CR. [F(2,15) = 4.635, p = 0.027]. Tukey’s post hoc test values are mean ± SEM

Discussion

Recently, there are growing reports regarding the beneficial effects of DR on many parameters of wellbeing, including life span, cognitive abilities, and neurodegeneration (Brownlow et al. 2014; Hadem et al. 2019; Speakman and Mitchell 2011). Moreover, CR was found protective in conditions of brain injury (Loncarevic-Vasiljkovic et al. 2016; Mychasiuk et al. 2015). Thus, the main goal of the present study was to assess the cognition-sparing effects of two different DR regimens, IF and CR, in closed-head mTBI mouse model. In order to address the mechanism of DR, we tested the potential involvement of SIRT1 in this process. We chose to focus on post-injury DR as a therapeutic strategy.

First, we evaluated the cognitive performance of mice using the NOR test. As expected from previous studies (Heim et al. 2017; Zohar et al. 2011), TBI caused significant impairment of memory 30 days post-injury in mice fed ad libitum. Both IF and CR significantly ameliorated this cognitive deficit. It was previously found that IF was neuroprotective in animal models of stroke and Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Anton et al. 2018; Longo and Mattson 2014). Here, we show that both IF and CR preserve visual memory function in our closed mTBI mouse model. IF and CR did not alter NOR memory in uninjured mice. Previous studies have shown that DR can enhance hippocampal neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity (Bele et al. 2015; Solari and Hangya 2018) and neurogenesis and axon elongation in brain regions, which are known to be involved in cognition (for review, see Solari and Hangya 2018). Previous reports have also shown that DR induces the expression of neurotrophic factors like BDNF and GDNF and has anti-inflammatory effects (Maalouf et al. 2009; Thrasivoulou et al. 2006; Ugochukwu and Figgers 2007). These reports suggest relevant mechanisms to the cognitive neuroprotection in mTBI models.

One of the most studied molecules that were reported to be involved in the health-enhancing effects of DR is SIRT1. It has been reported to be involved in improving aging and longevity in animal models (Guarente 2013; Ingram et al. 2007; Ran et al. 2015). In addition, it protects against neurodegeneration (Donmez 2012; Donmez et al. 2012). It is also involved in many metabolic functions such as glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, energy balance, and stress responses (Martin et al. 2015; Pasinetti et al. 2015). SIRT1 has been detected in the nucleus and cytoplasm, and interacts with nuclear and cytosolic proteins (Nogueiras et al. 2012). It was previously suggested to be part of the protection mechanism of DR in various situations, from aging to neurodegeneration. Hence, we wanted to test its involvement in the mechanism that underlies the cognitive impairment in our mTBI model and the effect of DR on SIRT1. Since we have chosen to focus on post-injury DR treatment, it was essential to perform the cognitive and biochemical analyses longer time points. Figures 2 and 4 show that, while CR induced a pronounced elevation in SIRT1 levels in the mice brains (the cortex and hippocampus), IF did not change its levels, implying of a potentially different effect of these two diets on SIRT1 mechanism. We then focused on the effect of TBI on SIRT1 levels in the two brain regions (the cortex and hippocampus) that play key roles important in cognition and memory. The following goal was to evaluate the effect of DR on the levels of SIRT1 in these regions while protecting cognition. Indeed, TBI significantly reduced the levels of SIRT1, suggesting a potential mechanism contributing to cognitive impairment (Stamatovic et al. 2018). Both CR and IF prevented the reduction in SIRT1 levels resulting from mTBI in the cortex, whereas only IF preserved SIRT1 levels in the hippocampus. These results suggest that the mechanisms by which IF and CR protect against cognitive impairment in mTBI may not be identical. To conclude, although both IF and CR ameliorated the cognitive deficits after mTBI, the mechanism could be different and may involve the region of interest.

TBI is a common cause of enduring cognitive deficits and behavioral alterations in the general public, contact sport athletes, and military personnel (Bogdanova and Verfaellie 2012; Manley et al. 2017). Moreover, while mTBI may not cause overt neuronal degeneration in the short-term, repeated concussions can result in a delayed progressive neurodegenerative process called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (Vos et al. 2018). As of yet, there are no effective treatments that can ameliorate cognitive deficits in patients that have suffered one or more mTBIs. IF is neuroprotective and neurorestorative in a wide range of animal models of brain injury and neurodegenerative disorders (Mattson 2012). DR was previously shown to protect neurons and improve functional outcome in animal models of stroke, epilepsy, and TBI when initiated prior to the brain injury (Arumugam et al. 2010; Bruce-Keller et al. 1999; Fann et al. 2014; Loncarevic-Vasiljkovic et al. 2016; Loncarevic-Vasiljkovic et al. 2012; Rich et al. 2010). In the present study, we show that IF and CR are effective in ameliorating cognitive deficits in a mTBI model when initiated after the brain injury. Our findings therefore suggest that IF and CR may prove effective in the treatment of TBI patients during the days and weeks following the head trauma.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Ari and Regine Aprijaskis Fund, at Tel-Aviv University and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval All applicable international, national, and/or, institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. If applicable (where such a committee exists), all procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agarwal S, Sharma S, Agrawal V, Roy N (2005) Caloric restriction augments ROS defense in S. cerevisiae, by a Sir2p independent mechanism. Free Radic Res 39:55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton SD, Moehl K, Donahoo WT, Marosi K, Lee SA, Mainous AG III, Leeuwenburgh C, Mattson MP (2018) Flipping the metabolic switch: understanding and applying the health benefits of fasting. Obesity (Silver Spring) 26:254–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam TV, Phillips TM, Cheng A, Morrell CH, Mattson MP, Wan R (2010) Age and energy intake interact to modify cell stress pathways and stroke outcome. Ann Neurol 67:41–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bele MS, Gajare KA, Deshmukh AA (2015) Caloric restriction mimetic 2-deoxyglucose maintains cytoarchitecture and reduces tau phosphorylation in primary culture of mouse hippocampal pyramidal neurons. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 51:546–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova Y, Verfaellie M (2012) Cognitive sequelae of blast-induced traumatic brain injury: recovery and rehabilitation. Neuropsychol Rev 22:4–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlow ML, Joly-Amado A, Azam S, Elza M, Selenica ML, Pappas C, Small B, Engelman R, Gordon MN, Morgan D (2014) Partial rescue of memory deficits induced by calorie restriction in a mouse model of tau deposition. Behav Brain Res 271:79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller AJ, Umberger G, McFall R, Mattson MP (1999) Food restriction reduces brain damage and improves behavioral outcome following excitotoxic and metabolic insults. Ann Neurol 45:8–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HC, Guarente L (2013) SIRT1 mediates central circadian control in the SCN by a mechanism that decays with aging. Cell 153:1448–1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DE, Supinski AM, Bonkowski MS, Donmez G, Guarente LP (2009) Neuronal SIRT1 regulates endocrine and behavioral responses to calorie restriction. Genes Dev 23:2812–2817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kruijk JR, Twijnstra A, Leffers P (2001) Diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis of mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 15:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhurandhar EJ, Allison DB, van Groen T, Kadish I (2013) Hunger in the absence of caloric restriction improves cognition and attenuates Alzheimer’s disease pathology in a mouse model. PLoS One 8: e60437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donmez G (2012) The effects of SIRT1 on Alzheimer’s disease models.Int J Alzheimers Dis 2012:509529 10.1155/2012/509529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donmez G, Arun A, Chung CY, McLean PJ, Lindquist S, Guarente L (2012) SIRT1 protects against alpha-synuclein aggregation by activating molecular chaperones. J Neurosci 32:124–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Fann DY, Santro T, Manzanero S, Widiapradja A, Cheng YL, Lee SY, Chunduri P, Jo DG, Stranahan AM, Mattson MP, Arumugam TV (2014) Intermittent fasting attenuates inflammasome activity in ischemic stroke. Exp Neurol 257:114–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Nikulina E, Mellado W, Filbin MT (2003) Neurotrophins elevate cAMP to reach a threshold required to overcome inhibition by MAG through extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent inhibition of phosphodiesterase. J Neurosci 23:11770–11777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve MW, Zink BJ (2009) Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Mt Sinai J Med 76:97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L (2013) Calorie restriction and sirtuins revisited. Genes Dev 27:2072–2085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haan MN (2006) Therapy insight: type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadem IKH, Majaw T, Kharbuli B, Sharma R (2019) Beneficial effects of dietary restriction in aging brain. J Chem Neuroanat 95:123–133. 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halagappa VK, Guo Z, Pearson M, Matsuoka Y, Cutler RG, Laferla FM, Mattson MP (2007) Intermittent fasting and caloric restriction ameliorate age-related behavioral deficits in the triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 26:212–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim LR, Bader M, Edut S, Rachmany L, Baratz-Goldstein R, Lin R, Elpaz A, Qubty D, Bikovski L, Rubovitch V, Schreiber S, Pick CG (2017) The invisibility of mild traumatic brain injury: impaired cognitive performance as a silent symptom. J Neurotrauma 34:2518–2528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Borg J, Neurotrauma Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury of the, W.H.O.C.C (2005) Summary of the WHO collaborating centre for neurotrauma task force on mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Med 37:137–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt ND, Hyun DH, Allard JS, Minor RK, Mattson MP, Ingram DK, de Cabo R (2006) Bioenergetics of aging and calorie restriction. Ageing Res Rev 5:125–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram DK, Young J, Mattison JA (2007) Calorie restriction in nonhuman primates: assessing effects on brain and behavioral aging. Neuroscience 145:1359–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert AJ, Merry BJ (2004) Effect of caloric restriction on mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production and bioenergetics: reversal by insulin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286:R71–R79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XH, Chen C, Tu Y, Sun HT, Zhao ML, Cheng SX, Qu Y, Zhang S(2013) Sirt1 promotes axonogenesis by deacetylation of Akt and inactivation of GSK3. Mol Neurobiol 48:490–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loncarevic-Vasiljkovic N, Pesic V, Todorovic S, Popic J, Smiljanic K, Milanovic D, Ruzdijic S, Kanazir S (2012) Caloric restriction suppresses microglial activation and prevents neuroapoptosis following cortical injury in rats. PLoS One 7:e37215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loncarevic-Vasiljkovic N, Milanovic D, Pesic V, Tesic V, Brkic M, Lazic D, Avramovic V, Kanazir S (2016) Dietary restriction suppresses apoptotic cell death, promotes Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl mRNA expression and increases the Bcl-2/Bax protein ratio in the rat cortex after cortical injury. Neurochem Int 96:69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo VD, Mattson MP (2014) Fasting: molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Cell Metab 19:181–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maalouf M, Rho JM, Mattson MP (2009) The neuroprotective properties of calorie restriction, the ketogenic diet, and ketone bodies. Brain Res Rev 59:293–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley G, Gardner AJ, Schneider KJ, Guskiewicz KM, Bailes J, Cantu RC, Castellani RJ, Turner M, Jordan BD, Randolph C, Dvorak J, Hayden KA, Tator CH, McCrory P, Iverson GL (2017) A systematic review of potential long-term effects of sport-related concussion. Br J Sports Med 51:969–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Tegla CA, Cudrici CD, Kruszewski AM, Azimzadeh P, Boodhoo D, Mekala AP, Rus V, Rus H (2015) Role of SIRT1 in autoimmune demyelination and neurodegeneration. Immunol Res 61:187–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP (2012) Energy intake and exercise as determinants of brain health and vulnerability to injury and disease. Cell Metab 16:706–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Duan W, Guo Z (2003) Meal size and frequency affect neuronal plasticity and vulnerability to disease: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Neurochem 84:417–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Longo VD, Harvie M (2017) Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res Rev 39:46–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Moehl K, Ghena N, Schmaedick M, Cheng A (2018) Intermittent metabolic switching, neuroplasticity and brain health. Nat Rev Neurosci 19:63–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister TW (2011) Neurobiological consequences of traumatic brain injury. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 13:287–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milman A, Rosenberg A, Weizman R, Pick CG (2005) Mild traumatic brain injury induces persistent cognitive deficits and behavioral disturbances in mice. J Neurotrauma 22:1003–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mychasiuk R, Hehar H, Ma I, Esser MJ (2015) Dietary intake alters behavioral recovery and gene expression profiles in the brain of juvenile rats that have experienced a concussion. Front Behav Neurosci 9:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueiras R, Habegger KM, Chaudhary N, Finan B, Banks AS, Dietrich MO, Horvath TL, Sinclair DA, Pfluger PT, Tschop MH (2012) Sirtuin 1 and sirtuin 3: physiological modulators of metabolism. Physiol Rev 92:1479–1514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasinetti GM, Wang J, Ho L, Zhao W, Dubner L (2015) Roles of resveratrol and other grape-derived polyphenols in Alzheimer’s disease prevention and treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta 1852:1202–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prozorovski T, Schulze-Topphoff U, Glumm R, Baumgart J, Schroter F,Ninnemann O, Siegert E, Bendix I, Brustle O, Nitsch R, Zipp F, Aktas O (2008) Sirt1 contributes critically to the redox-dependent fate of neural progenitors. Nat Cell Biol 10:385–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachmany L, Tweedie D, Rubovitch V, Yu QS, Li Y, Wang JY, Pick CG, Greig NH (2013) Cognitive impairments accompanying rodent mild traumatic brain injury involve p53-dependent neuronal cell death and are ameliorated by the tetrahydrobenzothiazole PFT-alpha. PLoS One 8:e79837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafalski VA, Ho PP, Brett JO, Ucar D, Dugas JC, Pollina EA, Chow LM, Ibrahim A, Baker SJ, Barres BA, Steinman L, Brunet A (2013) Expansion of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells following SIRT1 inactivation in the adult brain. Nat Cell Biol 15:614–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadori G, Fujikawa T, Anderson J, Berglund ED, Frazao R, Michan S, Vianna CR, Sinclair DA, Elias CF, Coppari R (2011) SIRT1 deacetylase in SF1 neurons protects against metabolic imbalance. Cell Metab 14:301–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran M, Li Z, Yang L, Tong L, Zhang L, Dong H (2015) Calorie restriction attenuates cerebral ischemic injury via increasing SIRT1 synthesis in the rat. Brain Res 1610:61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin JW, Shute M, Heffron SP, Saker KE (2006) Energy restriction but not protein source affects antioxidant capacity in athletes. Free Radic Biol Med 41:1001–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich NJ, Van Landingham JW, Figueiroa S, Seth R, Corniola RS, Levenson CW (2010) Chronic caloric restriction reduces tissue damage and improves spatial memory in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res 88:2933–2939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubovitch V, Ten-Bosch M, Zohar O, Harrison CR, Tempel-Brami C, Stein E, Hoffer BJ, Balaban CD, Schreiber S, Chiu WT, Pick CG (2011) A mouse model of blast-induced mild traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 232:280–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Kim HJ, Kobayashi M, Kitamura YI, Yokota-Hashimoto H, Shiuchi T, Minokoshi Y, Kitamura T (2010) Induction of hypothalamic Sirt1 leads to cessation of feeding via agouti-related peptide. Endocrinology 151:2556–2566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slemmer JE, Zhu C, Landshamer S, Trabold R, Grohm J, Ardeshiri A, Wagner E, Sweeney MI, Blomgren K, Culmsee C, Weber JT, Plesnila N (2008) Causal role of apoptosis-inducing factor for neuronal cell death following traumatic brain injury. Am J Pathol 173: 1795–1805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solari N, Hangya B (2018) Cholinergic modulation of spatial learning, memory and navigation. Eur J Neurosci 48:2199–2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speakman JR, Mitchell SE (2011) Caloric restriction. Mol Asp Med 32:159–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatovic SM, Martinez-Revollar G, Hu A, Choi J, Keep RF, Andjelkovic AV (2018) Decline in Sirtuin-1 expression and activity plays a critical role in blood-brain barrier permeability in aging. Neurobiol Dis. 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashlykov V, Katz Y, Gazit V, Zohar O, Schreiber S, Pick CG (2007) Apoptotic changes in the cortex and hippocampus following minimal brain trauma in mice. Brain Res 1130:197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashlykov V, Katz Y, Volkov A, Gazit V, Schreiber S, Zohar O, Pick CG (2009) Minimal traumatic brain injury induce apoptotic cell death in mice. J Mol Neurosci 37:16–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasivoulou C, Soubeyre V, Ridha H, Giuliani D, Giaroni C, Michael GJ, Saffrey MJ, Cowen T (2006) Reactive oxygen species, dietary restriction and neurotrophic factors in age-related loss of myenteric neurons. Aging Cell 5:247–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugochukwu NH, Figgers CL (2007) Caloric restriction inhibits up-regulation of inflammatory cytokines and TNF-alpha, and activates IL-10 and haptoglobin in the plasma of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Nutr Biochem 18:120–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos BC, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Sluiter JK (2018) Consequences of traumatic brain injury in professional American football players: a systematic review of the literature. Clin J Sport Med 28:91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar O, Schreiber S, Getslev V, Schwartz JP, Mullins PG, Pick CG (2003) Closed-head minimal traumatic brain injury produces long-term cognitive deficits in mice. Neuroscience 118:949–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar O, Rubovitch V, Milman A, Schreiber S, Pick CG (2011) Behavioral consequences of minimal traumatic brain injury in mice. Acta Neurobiol Exp 71:36–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]