Abstract

Mammals have developed a variety of antioxidant systems to protect them from the oxygen environment and toxic stimuli. Little is known about the mRNA abundance of antioxidant components during postnatal development of the liver. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the mRNA abundance of antioxidant components during liver development. Livers from male C57BL/6J mice were collected at 12 ages from prenatal to adulthood. The transcriptome was determined by RNA-Seq with transcript abundance estimated by Cufflinks. RNA-Seq provided a complete, more accurate, and unbiased quantification of the transcriptome. Among 33 known antioxidant components examined, three ontogeny patterns of liver antioxidant components were observed: (1) Prenatal-enriched, in which the mRNAs decreased from fetal livers to adulthood, such as metallothionein and heme oxygenase-1; (2) adolescent-rich and relatively stable expression, such as peroxiredoxins; and (3) adult-rich, in which the mRNA increased with age, such as catalase and superoxide dismutase. alternative splicing of several antioxidant genes, such as Keap1, Glrx2, Gpx3, and Txnrd1, were also detected by RNA-Seq. In summary, RNA-Seq revealed the relative abundance of hepatic antioxidant enzymes, which are important in protecting against the deleterious effects of oxidative stress.

Keywords: RNA-Seq, ontogeny, mouse liver, antioxidant

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

One of the major challenges in a biological system during development is to maintain cellular redox homeostasis through balancing the rate and magnitude of oxidant generation and oxidant detoxification [1]. An imbalance in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and adaptive antioxidant capacity will result in oxidative stress, a pathogenic stage that serves as both a cause and consequence of numerous acute toxicities and chronic diseases [2].

Newborns and especially preterm infants are susceptible to oxidative stress [3] and a delay in the development of protective pathways increases the risk of oxidative stress-induced pathogenesis in newborns [4]. Antioxidant mechanisms are crucial for prevention of oxidative stress-induced pathogenesis in newborns.

In general, there are three cellular antioxidant defense systems to protect against oxidative stress: low-molecular-weight antioxidants, enzymatic-antioxidant pathways, and free-ion sequestration. The major endogenous low-molecular-weight antioxidants include glutathione (GSH) and bilirubin.

GSH serves as the most abundant cellular thiol resource, and provides a buffer system to maintain cellular redox status. GSH is a tripeptide synthesized by gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase and glutathione synthetase. GSH reduces hydrogen and is also oxidized to its disulfide form (GSSG). GSSG is reduced to GSH through glutathione reductase using NADPH as the co-factor. Bilirubin, which is formed by biliverdin reductase, is the major degradation product of heme catabolism. Bilirubin reduces oxidative stress and becomes oxidized to biliverdin. The enzymatic antioxidant pathways include catalase, peroxiredoxin, and glutathione peroxidase. Catalase reduces two molecules of hydrogen peroxide into water, producing one molecule of singlet oxygen. Catalase is localized in peroxisomes and is found in every organ with particularly high concentrations in liver. Glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) reduces hydrogen peroxide to water and spontaneously oxidizes GSH into GSSG. The enzyme activity of Gpx is about one-tenth of catalase in multiple organs (i.e., liver, kidney, spleen, and lung) [5] , indicating a minor role of Gpx in detoxifying ROS. In addition, hydrogen peroxide can be reduced by peroxiredoxin (Prdx), resulting in oxidation of Prdx from the reduced form (Prdx-SH) to the oxidized form (Prdx-S-S-Prdx). Prdx-S-S-Prdx can be reduced to Prdx-SH through thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. If Prdx is further oxidized into the sulfinic acid form (Prdx-SOOH), it can be reduced by sulfiredoxin.

Transient metal ions (especially Fe2+ and Cu+) facilitate generation of hydroxyl free radicals from hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton-like reaction. Thus, free ion-binding proteins are important in preventing oxidative stress. Ferritin serves to store, deposit, and transfer iron in a non-toxic form [6]. Some heavy metals, including cadmium and mercury, readily bind to thiol groups of proteins, leading to disruption of redox homeostasis and protein damage. Metallothioneins are a family of low-molecular-weight cysteine-rich (22%−33%) proteins that bind endogenous and exogenous heavy metals. Metallothioneins are highly inducible upon heavy ion overload and metallothionein-bound metals are generally considered as non-toxic [7].

The Nrf2 antioxidant pathway is known to be the master defense pathway against oxidative stress [8]. Under quiescent conditions, Nrf2 interacts with the actin-anchored protein Keap1, largely localized in the cytoplasm to maintain low basal expression of Nrf2-regulated genes. Under oxidative conditions, Nrf2 is released from Keap1 and translocates to the nucleus to activate the expression of several dozen cytoprotective genes that enhance cell survival [9]. Activation of Nrf2 induces a panel of genes that promote low-molecular-weight antioxidants, enzymatic-antioxidant pathways, and freeion sequestration [10].

The next generation mRNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) provides a “true-quantification” of transcripts and an unbiased detection of transcript variants [11, 12]. We successfully used this technology to define developmental changes of cytochrome P450s [13, 14], transporters [15], phase II drug metabolizing enzymes [16], epigenetic enzymes in liver [17], and genes involved in hepatic energy metabolism [18, 19]. The purpose of this study was to quantify the mRNA abundance and transcript variants of the 35 major antioxidant genes in the liver for their relative abundance during development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Eight-week old C57BL/6J breeding pairs of mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). They were housed in an AAALAC accredited facility at the University of Kansas Medical Center. All animals were given ad libitum access to water and standard rodent chow (Harlan Teklad 8604, Halan Teklad, Madison, WI). Breeders were bred overnight and separated the next morning. Pups were weaned at 21-days of age. Livers were collected at the following 12 ages: day −2 (GD17.5 embryos from pregnant mothers were removed for tissue collection), day 0 (right after birth and before the start of suckling), day 1 (24 hours after birth), 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 45, and 60 (collected approximately at 8–10 am). Due to potential variations caused by the estrous cycle in maturing adult female mice, only male livers were used for this study (n = 3 per age, randomly selected from multiple litters). Livers were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

2.2. RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated using RNAzol Bee reagent (Tel-Test Inc., Friendswood, TX) per the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentrations were quantified using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) at a wavelength of 260 nm. Integrity of the total RNA samples was evaluated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA) and the samples with RNA integrity values above 7.0 were used for the RNA-Seq.

2.3. cDNA library preparation

The cDNA libraries from total RNA samples were prepared by an Illumina TruSeq RNA sample prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Three micrograms of total RNA were used as the RNA input according to recommendations of the manufacturer’s protocol. The mRNAs were selected from the total RNAs by purifying the poly-A containing molecules using poly-T primers. The RNA fragmentation, first and second strand cDNA syntheses, end repair, adaptor ligation, and PCR amplification were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The average size of the cDNA libraries was approximately 160 bp (excluding the adapters). The cDNA libraries were validated for RNA integrity and quantity using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA) before sequencing.

2.4. RNA-Sequencing

The cDNA libraries were clustered onto a TruSeq paired-end flow cell and sequenced for 100 bp paired-end reads (2 × 100) using a TruSeq 200 cycle SBS kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). For the initial run, a phi X 174 (PhiX) bacteriophage genome as well as a universal human reference RNA sample were used as controls on the Illumina HiSeq2000 sequencer (KUMC – Genome Sequencing Facility), and sequenced in parallel with other samples to ensure the data generated for each run are accurately calibrated during the image analysis and data analysis. In addition, the PhiX was spiked into each cDNA sample at approximately 1% as an internal quality control.

2.5. RNA-Seq data analysis

After the sequencing platform generated the sequencing images, the pixel-level raw data collection, image analysis, and base calling were performed by Illumina’s Real Time Analysis (RTA) software on a Dell PC attached to the HiSeq2000 sequencer. The base call files (*.BCL) were converted to qseq files by the Illumina’s BCL Converter and the qseq files were subsequently converted to FASTQ files for downstream analysis. The RNA-Seq reads from the FASTQ files were mapped to the mouse reference genome (NCBI37/mm10) and the splice junctions were identified by TopHat. The output files in BAM (Binary Alignment/Map) format were analyzed by Cufflinks to estimate the transcript abundance. The mRNA abundance was expressed in FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped).

2.6. Data visualization and statistics

The antioxidant genes were retrieved from the Cufflinks output for further analysis. Significant expression during at least one age of liver development was determined using the drop-in-deviance F test of the fitted FPKM data. The p-values were adjusted for extra Poisson variation and corrected for false discovery by the Benjamini-Hochberg method (FDR-BH) with a threshold of 0.05. A two-way hierarchical clustering dendrogram was generated by JMP v. 9.0 (SAS, Cary, NC) to determine the expression patterns of the mRNAs during liver development. The differential gene expression during liver development was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SPSS v. 16 and statistically significant differences were considered at p < 0.05 (Duncan’s multiple range test). The FPKM values were log2 transformed to achieve normal distribution prior to ANOVA.

3. Results

RNA-Seq generated an average of 175 million reads per sample and more than 80% of the reads were mapped to the mouse genome by TopHat. The mRNA ontogeny of antioxidant components was determined in livers of mice at 12 ages. These components include the genes involved in GSH synthesis and recycling, the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway, antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (Sod) and catalase, nonenzymatic components such as thioredoxin and glutaredoxin, and nucleoredoxin. In addition, transcript variants of antioxidant components were analyzed.

3.1. Ontogeny of genes involved in GSH synthesis, bilirubin synthesis, and the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway.

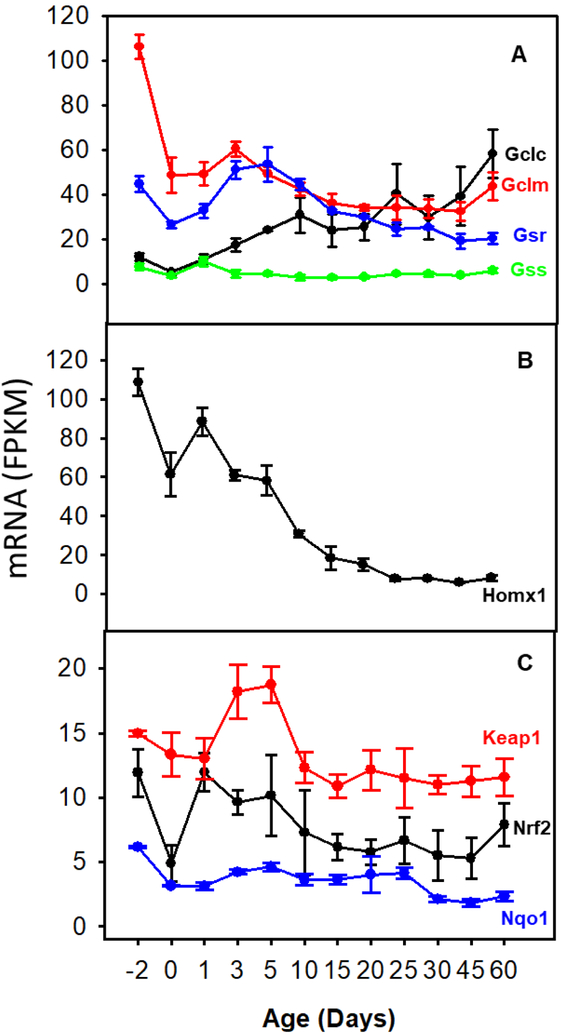

Figure 1A illustrates the changes in abundance during ontogeny of the mRNAs responsible for glutathione synthesis, including Gclc (glutamate cysteine ligase catalytic subunit), Gclm (glutamate cysteine ligase modifier), and glutathione synthetase (Gss) as well as glutathione reductase (Gsr). Gclc mRNA was low on Day-2 and gradually increased to a peak value by 60 days of age. In contrast, Gclm mRNA was highest at Day-2 and gradually decreased 56% by 60 days of age. Gsr mRNA abundance peaked at Day 5 and decreased 64% by 60 days of age. Gss mRNA was low throughout the developmental stages.

Fig. 1.

The mRNA ontogeny of (A) genes involve in GSH synthesis and reduction, (B) heme oxygenase-1, and (C) genes involve in the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Data are expressed as mean FPKM ± SE, n = 3.

Heme oxygenase is the enzyme that catalyzes heme into biliverdin, the precursor of the antioxidant bilirubin. Figure 1B depicts changes of heme oxygenase 1 (Homx1) during ontogeny. Homx1 mRNA was high at Day-2 and gradually decreased to 7% of peak level on Day 25 and remained low through Day 60.

Figure 1C shows the ontogeny changes of Nrf2, Keap1, and Nrf2-target gene NADPH quinone oxidoreductase 1 (Nqo1). Nrf2 mRNA abundance dropped to 42% of prenatal level at birth, increased to prenatal level at Day 1, and kept constant thereafter. The FPKM for Keap1 mRNA was relatively constant, but was 18% higher at 3 and 5 days of age. There was no significant change in the abundance of Nrf2 and Keap1 mRNA during development. Nqo1 mRNA was low at Day-2 and even lower at later ages.

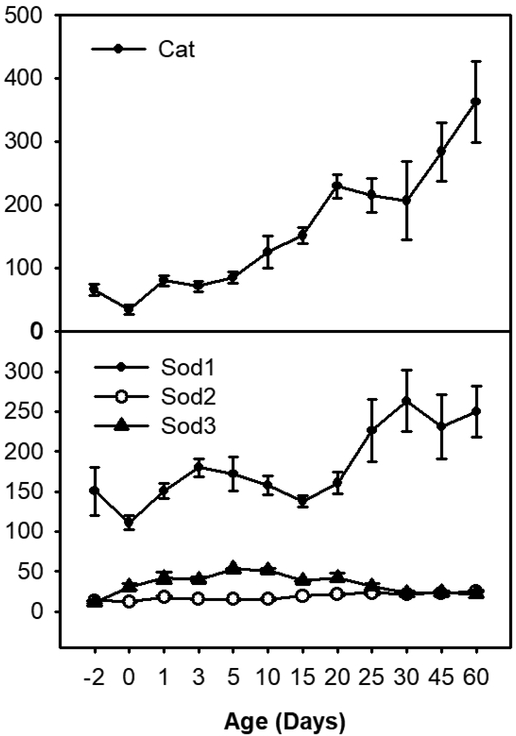

3.2. Ontogeny of catalase and superoxide dismutase

The ontogeny of the antioxidant enzyme catalase and superoxide dismutase is shown in Figure 2. Catalase increased with age, gradually increased to 189% of prenatal level at Day 10, and reached 6-fold of prenatal level at Day 60. SODs are a family of enzymes that catalyze the biotransformation of superoxide (O2−.) into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. Sod1 is located in the cytoplasm, Sod2 in the mitochondria, and Sod3 in extracellular fluid. Sod1 had the highest mRNA expression in the Sod gene family. Sod2 mRNA was the lowest with a FPKM of 14 at Day −2 and slightly increased through Day 60. Sod3 mRNA was low before birth, increased between Day 1 and Day 20, and then decreased to prenatal level at 60 days of age.

Fig. 2.

The mRNA ontogeny of (A) catalase and (B) superoxide dismutases. Data are expressed as mean FPKM ± SE, n = 3.

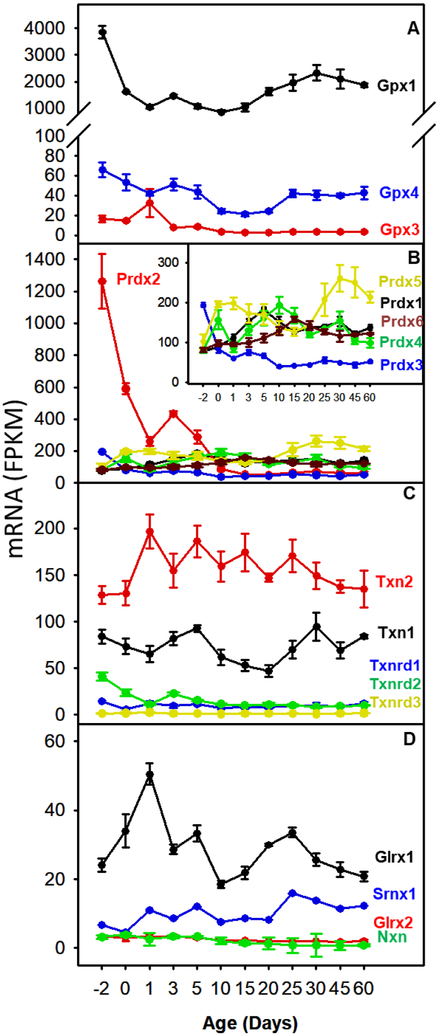

3.3. Ontogeny of glutathione peroxidase, peroxiredoxin, thioredoxin, and glutaredoxin

The relative abundance of glutathione peroxidases (Gpx) is depicted in the top panels of Figure 3. Gpx1 mRNA was the most and Gpx3 was the least abundant Gpx isoform. Gpx1 mRNA was 60-fold and 200-fold higher than Gpx4 and Gpx3 before birth, decreased 65% after birth, and remained constant until Day 60. Gpx2 mRNA abundance was minimal throughout the 60-day period (data not shown). The mRNA of Gpx3 and Gpx4 were relatively stable with age. Gpx3 mRNA increased 1.6-fold from Day −2 to Day 60; while Gpx4 mRNA decreased 61% from Day −2 to Day 60.

Fig. 3.

The mRNA ontogeny of (A) glutathione peroxidases, (B) peroxiredoxins, (C) thioredoxins and thioredoxin reductases, and (D) glutaredoxins and nucleoredoxin. Data are expressed as mean FPKM ± SE, n = 3.

The enzymes responsible for oxidized protein repair, including peroxiredoxin (Prdx1–6), thioredoxin, and glutaredoxin are shown in the Fig. 3B and 3C. At Day −2, the highest expression was Prdx2, which decreased rapidly after Day 10 to 5% of prenatal level. Prdx3 was the second most abundant Prdx at birth, but the lowest in adults. Prdx5 was low at Day −2, but became most abundant Prdx isoform by Day 60. Prdx1 and Prdx6 mRNA were also low and moderately increased after birth. Thus, Prdx2 was more abundant in fetal liver, but Prdx1, 5, and 6 were predominant in adult livers.

In general, the mRNAs of thioredoxin and glutaredoxin did not show any marked change with age. The abundance of Txn1 and Txn2 was maintained throughout development with Txn2 mRNA 50% to 2-fold higher than Txn2. Txnip was higher at birth, which gradually decreased to 65%. For glutaredoxins, Glrx was highest at Day 1, decreased to 60% at Day 10, and was maintained at this level. Srxn1 was low at Day −2 and slightly increased in adult mice. Glrx2 and Nxn mRNA levels were low and did not change during development.

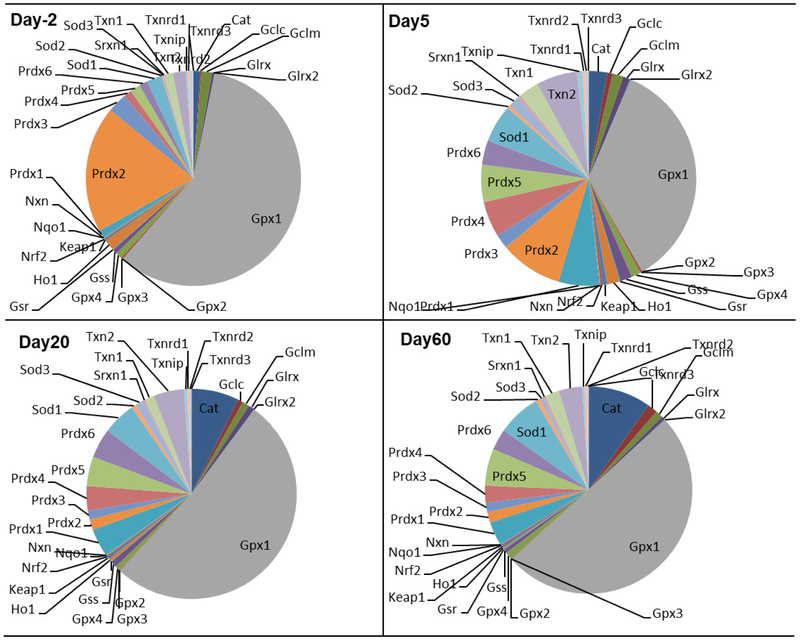

3.4. Relative abundance of major antioxidant components during development

The relative abundance of the mRNAs of 33 antioxidant enzyme genes during development is shown in Fig. 4. At Day −2, Gpx1 (58%) and Prdx2 (19%) were the most predominantly expressed, and others were less expressed: Prdx3 (2%), Sod1 (2%) while Cat, Gclm, Txn1, Txn2, Prdx1, Prdx4–6 were about 1%. At Day 5, the relative abundance of Gpx1 and Prdx2 decreased from 58% and 19% to 35% and 9%, respectively; while Txn2 increased from 1% to 6%; Prdx4 and Prdx5 increased to 5%; and Prdx6 and Txn1 increased to 3%. At Day 20, Gpx1 mRNA was still the most abundant (51%), but Prdx2 mRNA decreased to a low level (1%). Compared with the mRNA of other antioxidant genes, Cat mRNA was relatively more abundant (7%), followed by Prdx1 and Txn2 (4%). At adulthood (Day 60), the mRNA of Gpx1 was still the most abundant (49%), followed by Cat (9%), SOD (7%), Prdx5 (6%), and Prdx1 (4%). In general, the mRNA of antioxidant genes was most abundant at Day −2, when total FPKM values were higher than 6,600. In contrast, the total FPKM value of antioxidant genes decreased to 3,000 FPKM from Day 0 to Day 60.

Fig. 4.

Relative proportions of mRNAs of antioxidant genes during liver development as visualized by pie charts. Four representative ages are shown, namely day −2 (prenatal), day 5 (neonatal), day 20 (adolescent), and day 60 (adult).

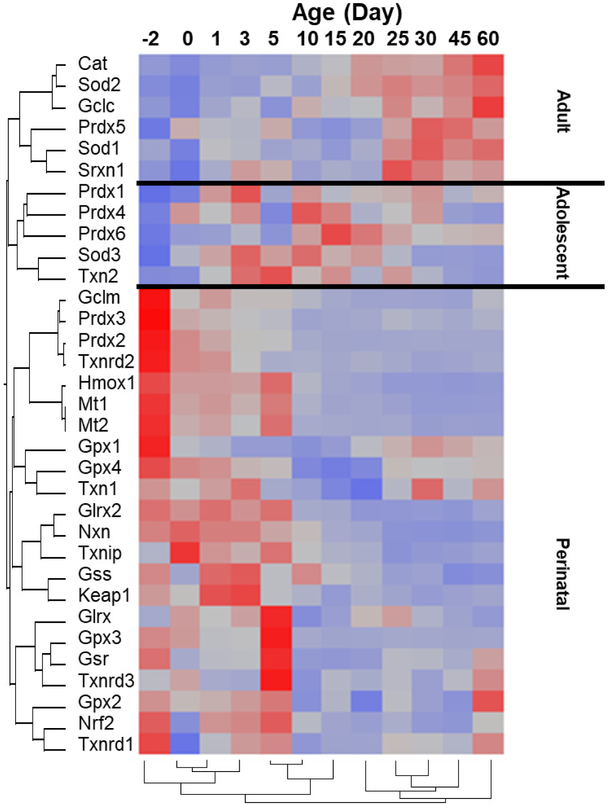

3.5. Patterns of expression of antioxidant genes during liver development

Figure 5 is a heat map that shows the pattern of abundance of the antioxidant genes during development. Most of the antioxidant genes were enriched during the perinatal stage. During the adolescent period, peroxiredoxins (Prdx1, Prdx4, Prdx6), Sod3, and Txn2 were expressed at their highest level. In adult mice, Cat, Sod1, Sod2, Gclc, Prdx5, and Srxn1 were expressed at their highest level.

Fig. 5.

A two-way hierarchical clustering dendrogram of the mRNAs of the 33 antioxidant genes that are significantly expressed during liver development. Data are expressed as mean FPKM, standardized, and visualized by JMP v9.0 (SAS). Red: relatively high expression; blue: relatively low expression.

3.6. Novel isoforms of antioxidant variants during liver development

Figure 6 illustrates transcript variants in livers of mice at various ages. For the 4 transcript variants of Glrx2, variant 1 (NM_001038592), which is the longer transcript, was the major isoform in mouse liver throughout development. Other variants of Glrx2 (NM_001038593, NM_023505, NM_001038594) were very lowly expressed throughout liver development and no apparent change in ontogeny was observed. Four Keap1 transcription variants (NM_001110305, NM_001110306, NM_001110307, and NM_016679) encode the same protein. NM_001110307 was the predominant variant, which was highest between Day 1 and Day 5 (5–10 FPKM). Gpx3 had two transcription variants: variant 1 (NM_001083929) represents the longest transcript, which was highest on Day 1 of age and decreased thereafter to 17% of prenatal level at Day 60 of age. Variant 2 (NM_008161) was lowly expressed at all ages during liver development in mice. Txnrd1 had four transcription variants: variant 1 (NM_001042513) was the abundant transcript and maintained stable abundance throughout liver development. Compared with variant 1, variant 2 (NM_015762) was also moderately expressed, while the other variants (NM_001042523, NM_001042514) were lowly expressed. Gpx4 had two transcription variants: variant 1 (NM_008162) was the dominant variant with abundance markedly higher than variant 2 (NM_001037741) throughout development stages. Txnrd3 had 2 variants with variant NM_001178058 predominant, while variant NM_001178058 was lowly expressed throughout liver development.

Fig. 6.

The FPKM values of known mRNA isoforms of six genes involve in antioxidant defense that are significantly expressed during liver development. Data are expressed as mean FPKM ± SE (n = 3) and visualized by SigmaPlot (v11.0).

4. Discussion

Changes in the expression of antioxidant components are important in affecting the body defense against various toxic stimuli, because these changes are critical in regulating free radical scavenge as well as the repair of oxidized proteins during liver development [20, 21]. The present study clearly shows three patterns of abundance of 33 antioxidant genes during development, adding to the evolving knowledge on antioxidant enzymes and other non-enzymatic proteins protecting against oxidative stress in the liver.

GSH is the most abundant cellular thiol and directly reduces hydrogen peroxide to water at the expense of oxidizing GSH to its disulfide (GSSG), either non-enzymatically or through glutathione peroxidase (Gpx). GSSG is reduced to GSH by glutathione reductase (Gsr). The Gpx-GSH pathway is also a major intracellular mechanism that prevents lipid peroxidation [22], DNA fragmentation [23], and protein adduction [24]. Age-related changes in GSH antioxidant components are associated with various diseases [25, 26], including liver diseases [27]. In rat liver, GSH content, Gsr and Gpx activity are reported to be low during the perinatal period and activity increases to adult levels by late post-weaning [28]. In contrast, the present study shows in mice that the abundance of Gsr and Gpx mRNA is high at neonatal ages, decreases during the perinatal period, and remains constant to the adult period (Fig. 1A and Fig. 3A).

The Nrf2 antioxidant pathway is a master regulator of the defense system against oxidative stress [29]. Nrf2 is a transcription factor that positively regulates the basal and inducible expression of a large battery of antioxidant genes [10]. During development, Nrf2 and Keap1 are stably expressed with no apparent change during ontogeny. Given the fact that the activity of Nrf2 is regulated through dissociation from Keap1, the mRNAs of Nrf2 target genes are most relevant to indicate Nrf2 activity during development. However, some of the Nrf2 target genes exhibit diverse expression patterns during development. For example, Nqo1 shows a slight decrease from prenatal to adulthood, Gss remains constantly low at all ages, Gclm was increased from prenatal (10 FPKM) to adult (60 FPKM), and Gclc decreased from 100 FPKM in prenatal to 40 FPKM after birth. Thus, Nrf2 itself may not be the major regulator of the antioxidant genes during development.

Our previous genome-wide analyses of developmental changes of hepatic transcriptome indicate that in the prenatal and neonatal group, c-Myc has the highest number of associated upstream regulators, followed by p53 [18]. Prdx2, Gclc, and Gclm have been reported as direct target genes induced by c-Myc to ameliorate oxidative stress [30]. In contrast, c-Myc has been reported as a Nrf2-interacting protein that negatively regulates phase II genes through electrophile responsive elements [31]. p53 mediates the induction of metallothionein by metals [32]. Moreover, direct interaction between Nrf2 and p21 (Cdkn1a), the p53-target gene upregulates the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response [33]. Additionally, activation of NF-kB induces hepatic expression of Nqo1 and Gpx1 [34]. c-Myc, p53, p21, and NF-kB are expressed at much higher levels in perinatal livers than adult livers [18]. Thus, higher perinatal levels of c-Myc, p53, p21, and NF-kB may help explain the generally higher expression of most antioxidant genes, particularly Prdx2, Mt1, Mt2, Nqo1, and Gpx1 in perinatal livers than adult livers.

There are two types of antioxidant defense systems in the organism: enzyme reaction systems and non-enzymatic systems. Antioxidant enzymes, including Sod and Cat, produce a long-acting antioxidant and detoxification effects and Sod-null mice are susceptible to age-related diseases [35]. Both Cat and Sod1 abundance increases with age, indicating increasing capacity of these enzymatic antioxidant systems with age.

The endogenous reductants are thioredoxins and glutaredoxins, small ubiquitous proteins with two redox-active cysteines in their active centers [36]. Prdx2 showed a similar developmental pattern as Mt1 and Mt2, which decreased from 1,300 FPKM in prenatal to about 200 FPKM in adult mice, while other Prdx isoforms including Prdx1, 3, 4, and 5 are lowly expressed throughout development. The relative abundance of Txn2 and Txn1 is more than Txnrd1–3 and remained stable throughout development. Heme oxygenase is the enzyme that catalyzes heme into biliverdin, the precursor of the antioxidant bilirubin. Expression of homx1 in mouse liver decreased during development. This pattern was also observed in rat ontogeny [37], implicating decreased heme catabolism and bilirubin synthesis during liver development [38].

The next generation of mRNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) provides a “true-quantification” of transcripts and makes the comparison of mRNA abundance among multiple genes possible [11, 12]. The present study shows that Gpx1 is the predominant antioxidant gene at all developmental ages in liver of mice. In the present study, of the 33 antioxidant genes quantified, Gpx1 mRNA consists of 50% of the abundance of mRNA, indicating the crucial role of GSH-Gpx1 pathway in antioxidant defense during development and adulthood.

The next generation of mRNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) also uncovers quantitative information on transcription variants that encodes different isoforms of protein. These different isoforms may have distinct cellular localizations and involve in diverse physiological functions. For Glrx2, NM_001038592 encodes isoform a (Glrx2a), and NM_001038593, NM_001038594, and NM_023505 encode a shorter isoform b (Glrx2b) that lacks amino acid residues 1 – 33. There is no report on functional differences of mouse Glrx2a and Glrx2b. Human Glrx2a functions in mitochondrial redox homeostasis and is important for the protection against and recovery from oxidative stress [39]. Human Glrx2b localizes in the cytosol and nucleus and potentially involved in tumor progression [40] and osteoclastogenesis [41]. NM_001038592 is the predominant transcript of Glrx, indicating that Glrx2a is the predominant enzyme isoform throughout development. Txnrd1 has four transcript variants resulting from alternative splicing at the 5’ end: NM_001042513, NM_001042514, and NM_015762 encode the common 55 kDa form, and NM_001042523 encodes a N-terminally elongated form of 67 kDa [42]. The multitude of Txnrd1 transcripts with different 5’-ends probably reflect alternative post-transcriptional regulation as well as regulation by cell- or growth condition-specific switches to transcription from alternative promoters [42]. Among glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) superfamily, Gpx4 is unique because it reduces peroxides of complex lipids as well as hydroperoxide-associated membranes. Gpx4 transcript variant NM_008162 encodes the mitochondrial form (m-Gpx4), and NM_001037741 encodes the nuclear form (n-Gpx4). M-Gpx4 was shown to be dispensable in mouse embryonic development but essential for sperm development [43]. The predominant expression of NM_008162 indicates abundant m-Gpx4 as opposed to n-Gpx4. For most of antioxidant related genes, tissue distribution and the function of protein products of their splicing variants is unknown. The present study revealed the expression patterns in mouse liver, and provided novel insights of their role in development.

Among the 33 known antioxidant components examined, three ontogeny patterns were observed: (1) Prenatal-rich genes with mRNAs that decreased from fetal livers to adulthood (example: Homx-1 and Gclm); (2) adolescent-rich and relatively stable expression (example: peroxiredoxins); and (3) adult-rich genes with mRNAs that increased with age (example: Cat, Sod1, and Sod2). It is interesting to note that the basal expression of more than 80% of the antioxidant genes is higher in prenatal or adolescent age than in adulthood.

In summary, the present study utilized RNA-Seq technology to profile major antioxidant components in mouse liver during development. Among the 33 antioxidant components examined, three ontogeny patterns were observed: prenatal-rich, adolescent-rich, and adult-rich expression. Transcript variants of several antioxidant genes were also detected by RNA-Seq. Thus, RNA-Seq revealed the relative abundance of hepatic antioxidant enzymes and this quantitative change during development.

Highlights:

Three ontogeny patterns of liver antioxidant components were observed: prenatal-, adolescent- and adult-enriched

Most of the antioxidant genes were enriched during the perinatal stage

Prdx1, Prdx4, Prdx6, Sod3, and Txn2 were adolescent enriched

Cat, Sod1, Sod2, Gclc, Prdx5, and Srxn1 were adult enriched

Gpx1 had highest mRNA abundance out of 33 antioxidant enzyme genes during development

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Clark Bloomer from the KUMC Sequencing Core Facilities for his technical assistance with mRNA-Seq; Lai Peng for contributions in tissue collection and research discussion, as well as Dr. Sumedha Guewardena and Byunggl Yoo for technical assistance in bioinformatics. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants [GM111381, ES019487, ES025708, and GM118367], the University of Washington Center for Exposures, Diseases, Genomics, and Environment [P30 ES0007033], and the Murphy Endowment.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Cat

Catalase

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped

- Gclc

glutamate cysteine ligase catalic

- Gclm

glutamate cysteine ligase modifier

- Glrx

glutaredoxin

- Gpx

glutathione peroxidase

- GSH

glutathione

- Gss

glutathione synthase

- GSSG

Glutathione disulfide

- Gsr

glutathione reductase

- GTF

gene transfer format

- IGV

Integrative Genomics Viewer

- Homx1

heme oxygenase 1

- Keap1

kelch-like ECH associating protein 1

- Mt

metallothionein

- Nqo1

NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1

- Nrf2

nuclear factor, erythroid derived 2, like 2

- Nxn

nucleoredoxin

- Prdx

peroxiredoxin

- Sod

Superoxide dismutase

- Srnx1

sulphiredoxin 1 homolog

- Txn

thioredoxin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests and conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Schippers JH, Nguyen HM, Lu D, Schmidt R, Mueller-Roeber B, ROS homeostasis during development: an evolutionary conserved strategy, Cell Mol Life Sci (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Firuzi O, Miri R, Tavakkoli M, Saso L, Antioxidant therapy: current status and future prospects, Curr Med Chem 18(25) (2011) 3871–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Saugstad OD, Bronchopulmonary dysplasia-oxidative stress and antioxidants, Semin Neonatol 8(1) (2003) 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Davis JM, Auten RL, Maturation of the antioxidant system and the effects on preterm birth, Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 15(4) (2010) 191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Marklund SL, Westman NG, Lundgren E, Roos G, Copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase, manganese-containing superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase in normal and neoplastic human cell lines and normal human tissues, Cancer Res 42(5) (1982) 1955–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Arosio P, Levi S, Cytosolic and mitochondrial ferritins in the regulation of cellular iron homeostasis and oxidative damage, Biochim Biophys Acta 1800(8) (2010) 783–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Klaassen CD, Liu J, Choudhuri S, Metallothionein: an intracellular protein to protect against cadmium toxicity, Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 39 (1999) 267–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Baird L, Dinkova-Kostova AT, The cytoprotective role of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway, Arch Toxicol 85(4) (2011) 241–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N, Biswal S, Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway, Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47 (2007) 89–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wu KC, Cui JY, Klaassen CD, Beneficial role of Nrf2 in regulating NADPH generation and consumption, Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology 123(2) (2011) 590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Blencowe BJ, Ahmad S, Lee LJ, Current-generation high-throughput sequencing: deepening insights into mammalian transcriptomes, Genes Dev 23(12) (2009) 1379–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fullwood MJ, Wei CL, Liu ET, Ruan Y, Next-generation DNA sequencing of paired-end tags (PET) for transcriptome and genome analyses, Genome Res 19(4) (2009) 521–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Peng L, Cui JY, Yoo B, Gunewardena SS, Lu H, Klaassen CD, Zhong XB, RNA-sequencing quantification of hepatic ontogeny of phase-I enzymes in mice, Drug Metab Dispos 41(12) (2013) 2175–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Peng L, Yoo B, Gunewardena SS, Lu H, Klaassen CD, Zhong XB, RNA sequencing reveals dynamic changes of mRNA abundance of cytochromes P450 and their alternative transcripts during mouse liver development, Drug Metab Dispos 40(6) (2012) 1198–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cui JY, Gunewardena SS, Yoo B, Liu J, Renaud HJ, Lu H, Zhong XB, Klaassen CD, RNA-Seq reveals different mRNA abundance of transporters and their alternative transcript isoforms during liver development, Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology 127(2) (2012) 592–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lu H, Gunewardena S, Cui JY, Yoo B, Zhong XB, Klaassen CD, RNA-sequencing quantification of hepatic ontogeny and tissue distribution of mRNAs of phase II enzymes in mice, Drug Metab Dispos 41(4) (2013) 844–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lu H, Cui J, Gunewardena S, Yoo B, Zhong XB, Klaassen C, Hepatic ontogeny and tissue distribution of mRNAs of epigenetic modifiers in mice using RNA-sequencing, Epigenetics 7(8) (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gunewardena SS, Yoo B, Peng L, Lu H, Zhong X, Klaassen CD, Cui JY, Deciphering the Developmental Dynamics of the Mouse Liver Transcriptome, PLoS One 10(10) (2015) e0141220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Renaud HJ, Cui YJ, Lu H, Zhong XB, Klaassen CD, Ontogeny of hepatic energy metabolism genes in mice as revealed by RNA-sequencing, PLoS One 9(8) (2014) e104560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Liang QN, Sheng YC, Jiang P, Ji LL, Xia YY, Min Y, Wang ZT, The difference of glutathione antioxidant system in newly weaned and young mice liver and its involvement in isoline-induced hepatotoxicity, Arch Toxicol 85(10) (2011) 1267–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Turcot V, Rouleau T, Tsopmo A, Germain N, Potvin L, Nuyt AM, Lavoie JC, Long-term impact of an antioxidant-deficient neonatal diet on lipid and glucose metabolism, Free Radic Biol Med 47(3) (2009) 275–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Imai H, Nakagawa Y, Biological significance of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx, GPx4) in mammalian cells, Free Radic Biol Med 34(2) (2003) 145–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Higuchi Y, Glutathione depletion-induced chromosomal DNA fragmentation associated with apoptosis and necrosis, J Cell Mol Med 8(4) (2004) 455–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Biswas SK, Rahman I, Environmental toxicity, redox signaling and lung inflammation: the role of glutathione, Mol Aspects Med 30(1–2) (2009) 60–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sanz N, Diez-Fernandez C, Alvarez A, Cascales M, Age-dependent modifications in rat hepatocyte antioxidant defense systems, J Hepatol 27(3) (1997) 525–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang C, Rodriguez C, Spaulding J, Aw TY, Feng J, Age-dependent and tissue-related glutathione redox status in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, J Alzheimers Dis 28(3) (2012) 655–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Toroser D, Sohal RS, Age-associated perturbations in glutathione synthesis in mouse liver, Biochem J 405(3) (2007) 583–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Elbarbry F, Alcorn J, Ontogeny of glutathione and glutathione-related antioxidant enzymes in rat liver, Res Vet Sci 87(2) (2009) 242–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Reisman SA, Yeager RL, Yamamoto M, Klaassen CD, Increased Nrf2 activation in livers from Keap1-knockdown mice increases expression of cytoprotective genes that detoxify electrophiles more than those that detoxify reactive oxygen species, Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology 108(1) (2009) 35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Benassi B, Zupi G, Biroccio A, Gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase mediates the c-Myc-dependent response to antineoplastic agents in melanoma cells, Molecular pharmacology 72(4) (2007) 1015–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Levy S, Forman HJ, C-Myc is a Nrf2-interacting protein that negatively regulates phase II genes through their electrophile responsive elements, IUBMB life 62(3) (2010) 237–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ostrakhovitch EA, Olsson PE, von Hofsten J, Cherian MG, P53 mediated regulation of metallothionein transcription in breast cancer cells, Journal of cellular biochemistry 102(6) (2007) 1571–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chen W, Sun Z, Wang XJ, Jiang T, Huang Z, Fang D, Zhang DD, Direct interaction between Nrf2 and p21(Cip1/WAF1) upregulates the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response, Molecular cell 34(6) (2009) 663–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lu H, Lei X, Zhang Q, Moderate activation of IKK2-NF-kB in unstressed adult mouse liver induces cytoprotective genes and lipogenesis without apparent signs of inflammation or fibrosis, BMC gastroenterology 15 (2015) 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Olofsson EM, Marklund SL, Behndig A, Enhanced age-related cataract in copper-zinc superoxide dismutase null mice, Clin Experiment Ophthalmol (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lu J, Holmgren A, Thioredoxin System in Cell Death Progression, Antioxid Redox Signal (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Watanabe T, Hasegawa G, Yamamoto T, Hatakeyama K, Suematsu M, Naito M, Expression of heme oxygenase-1 in rat ontogeny, Arch Histol Cytol 66(2) (2003) 155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Muniz P, Garcia Barchino MJ, Iradi A, Mahiques E, Marco V, Oliva MR, Saez GT, Age-related changes of liver antioxidant enzymes and 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine during fetal-neonate transition and early rat development, IUBMB Life 49(6) (2000) 497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kim SJ, Jung HJ, Choi H, Lim CJ, Glutaredoxin 2a, a mitochondrial isoform, plays a protective role in a human cell line under serum deprivation, Mol Biol Rep 39(4) (2012) 3755–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lonn ME, Hudemann C, Berndt C, Cherkasov V, Capani F, Holmgren A, Lillig CH, Expression pattern of human glutaredoxin 2 isoforms: identification and characterization of two testis/cancer cell-specific isoforms, Antioxid Redox Signal 10(3) (2008) 547–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yeon JT, Choi SW, Park KI, Choi MK, Kim JJ, Youn BS, Lee MS, Oh J, Glutaredoxin2 isoform b (Glrx2b) promotes RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis through activation of the p38-MAPK signaling pathway, BMB Rep 45(3) (2012) 171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sun QA, Zappacosta F, Factor VM, Wirth PJ, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN, Heterogeneity within animal thioredoxin reductases. Evidence for alternative first exon splicing, J Biol Chem 276(5) (2001) 3106–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ufer C, Wang CC, The Roles of Glutathione Peroxidases during Embryo Development, Front Mol Neurosci 4 (2011) 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]