Abstract

Objective:

Low concentrations of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid-beta (Aβ-42) are associated with increased risk of cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease (PD). We sought to determine whether APOE genotype modifies the rate of cognitive decline in PD patients with low CSF Aβ-42 compared to patients with normal levels.

Methods:

The Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative is a longitudinal, ongoing study of de novo PD participants, which includes APOE genotyping, CSF Aβ-42 determinations, and neuropsychological assessments. We used linear mixed effects models in three PD groups (PD participants with low CSF Aβ at baseline, PD participants with normal CSF Aβ, and both groups combined). Having at least one copy of the APOE ε4 allele, time, and the interaction of APOE ε4 and time were predictor variables for cognitive change, adjusting for age, gender and education.

Results:

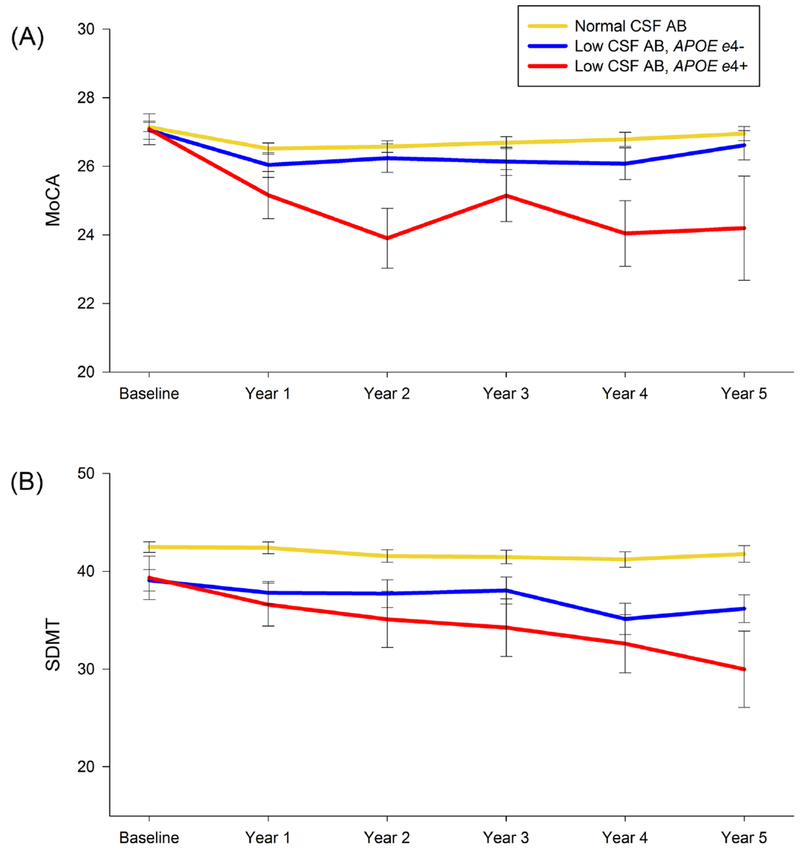

423 de novo PD participants were followed up to 5 years with annual cognitive assessments. 103 participants had low baseline CSF Aβ-42 (39 APOE ε4+, 64 APOE ε4−). Compared to participants with normal CSF Aβ-42, those with low CSF Aβ-42 declined faster on most cognitive tests. Within the low CSF Aβ-42 group, APOE ε4+ participants had faster rates of decline on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (primary outcome; 0.57 points annual decline, p=0.005; 5-year standardized change of 1.2) and the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (1.4 points annual decline, p=0.002; 5-year standardized change of 0.72).

Discussion:

PD patients with low CSF Aβ-42 and APOE ε4+ showed a higher rate of cognitive decline early in the disease. Tests of global cognition (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) and processing speed (Symbol Digit Modalities Test) were the most sensitive to early cognitive decline. Results suggest that CSF Aβ-42 and APOE ε4 might interact to promote early cognitive changes in PD patients.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, cognitive impairment, APOE ε4, amyloid, cerebrospinal fluid

INTRODUCTION

Cognitive impairment and dementia are among the most devastating symptoms in Parkinson’s disease (PD) (1–3). While it is now clear that all PD patients are at risk for eventual cognitive decline, the individual rate of decline is highly variable with some patients exhibiting dementia at 5 years and others only mildly impaired at 20 years. At the time of diagnosis, most PD patients (60-85%) are cognitively normal (4–6), but over the first three years of disease, approximately one-third of cognitively normal patients will progress to mild cognitive impairment (7). Those demonstrating mild cognitive impairments are then at higher risk of developing dementia (7, 8). Therefore, recognizing patients at the time of diagnosis who are at higher risk of early cognitive decline could also identify those at risk of earlier dementia, which is important to anticipate given its association with a greater loss of employment, caregiver stress and fatigue, increased cost to health systems, patient institutionalization, and decreased survival (9–17). Further, differentiating those patients at high risk for dementia as early as possible has therapeutic implications, since treatment is likely to be most effective prior to the onset of demonstrable cognitive decline.

By 15 years of disease, about half of PD patients will meet diagnostic criteria for dementia (2, 18), but identifying those who will dement has been difficult. The most commonly reported predictors of dementia are older age at PD diagnosis, male gender, and longer duration of motor symptoms (2, 18–22). However, age, gender and duration alone do not explain the wide variance in risk for cognitive decline. Several longitudinal studies have identified other biomarkers predictive of cognitive decline in early PD. The most robust is cerebral amyloid, as assessed by CSF Aβ (23) or amyloid PET imaging (24). While some cross-sectional studies in PD did not find a relationship between low CSF Aβ or PET amyloid positivity (24–26), other studies showed that low CSF Aβ is correlated with poor memory (27–29) and global cognitive impairment (30) in non-demented PD patients. To date, most longitudinal studies in PD agree that abnormal Aβ is linked to future cognitive decline (23).

Other studies suggest that PD patients with at least one copy of the APOE ε4 allele are at higher risk of developing cognitive impairment and dementia (31). The APOE ε4 allele is more common in PD patients with dementia and in patients with Dementia with Lewy Bodies (32). A recent large-scale multisite genetic study found that APOE ε4 was over represented in PD patients with dementia compared to those without cognitive impairment (31), even in PD patients with a pure synucleinopathy at autopsy (33). In PD patients, the APOE ε4 genotype is found to be specifically associated with poor episodic memory and semantic verbal fluency, but not visuospatial and executive impairments (31). However, other cross-sectional studies have failed to replicate this relationship between APOE ε4 genotype and cognitive impairment in PD (34). Therefore, it is possible APOE ε4 only confers risk in a subset of PD patients. Finally, few studies have explored the relationship between APOE ε4 genotype and early cognitive decline during the first several years after diagnosis. No studies have determined whether there is an interaction between APOE ε4 genotype and abnormalities in CSF Aβ related to cognitive decline in patients with PD.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants

Participants enrolled in the Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI), an observational, international, longitudinal study that aims to identify biomarkers of PD progression (35, 36). PPMI enrolled 423 drug-naive, early stage PD patients into the de novo cohort and 196 age-matched healthy controls (HC) from 24 clinical sites in the United States, Europe and Australia. PPMI participants were within 2 years of PD diagnosis and not expected to require PD medications within 6 months. Patients were excluded if they had a clinical diagnosis of dementia, had MRI evidence of another clinically significant neurological disease, or were unable to tolerate a lumbar puncture. Clinical characteristics, CSF, and cognitive assessments were recorded at baseline and at annual follow up. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and all PPMI sites received approval from their respective ethics committees on human experimentation prior to study initiation. We obtained data on key variables (below) from the PPMI database on July 17th, 2018 (www.ppmi-info.org/data) and included all available data from baseline through the year 5 visit.

Cognitive Assessment

Baseline cognitive testing, which was repeated at each annual follow up, included six cognitive tests. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a test of global cognition, and assesses aspects of attention and concentration, executive function, memory, language, visuospatial skills, conceptual thinking, calculations, and orientation (37). The MoCA has been validated as a sensitive measure of cognitive impairment and decline in PD (38, 39) and was therefore chosen as the primary cognitive outcome measure. We included the additional cognitive tests as secondary cognitive outcome measures. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) measures episodic verbal memory and is comprised of 3 learning trials (Immediate Recall), a delayed recall trial (Delayed Recall), and a recognition trial (40). A Recognition Discrimination Index is calculated as the delayed recall trial score minus the number of related false positives. The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) assesses visual scanning, attention, and processing speed (41, 42). Letter Number Sequencing assesses auditory working memory (43). The Semantic verbal Fluency Test assesses spontaneous word production that is dependent upon semantic memory and executive cognitive processes (44). Finally, the Judgement of Line Orientation is a motor-free measure of visuospatial perception and orientation (45). We evaluated scores from each of these cognitive measures at six time points (Baseline, Years 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5).

CSF Analyses

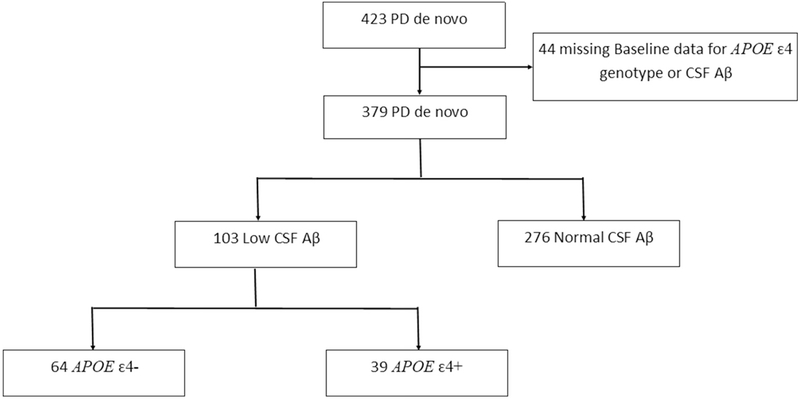

CSF samples were collected at baseline by standardized lumbar puncture procedures and analyzed as described in the PPMI biologies manual (http://ppmi-info.org) and previously reported (46, 47). Participants with missing CSF Aβ or APOE ε4 genotype data at baseline were excluded from our analysis (Figure 1). To address our primary aim to determine the interaction between low CSF Aβ and APOE ε4 genotype in predicting cognitive decline in PD participants, we used the CSF Aβ-42 values of the HC group to determine our cutoff for low CSF Aβ. A priori, we defined low CSF Aβ as values less than 310.3 pg/mL, which is the low quartile for the HC Aβ values (Q1 = 310.3, Q2(median) = 378.2, Q3 = 439.4). Of the 379 de novo PD participants with baseline CSF Aβ data, 276 PD participants had normal CSF Aβ and 103 PD participants had low CSF Aβ.

Figure 1:

Flowchart of Study Cohort. Flowchart illustrates the selection of PPMI study cohort according to CSF and genetic information.

APOE = Apolipoprotein E; APOE ε4+ = presence of at least one APOE ε4 allele; APOE ε4− = absence of APOE ε4 allele; CSF Aβ = Cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid Beta.

Genetic Analyses

At baseline, blood samples were collected from all participants, and genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood. APOE genotypes were determined using allele-specific oligonucleotide probes labeled with fluorogenic reporter (TaqMan method), as previously described (47, 48). Within each CSF group (low CSF Aβ and normal CSF Aβ), we defined APOE ε4+ by the presence of at least one APOE ε4 allele and APOE ε4− as no APOE ε4 allele (Figure 1). Of the 39 PD participants in the low CSF Aβ APOE ε4+ group, three had two APOE ε4 alleles. Of the 61 PD participants in the normal CSF Aβ APOE ε4+ group, six had two APOE ε4 alleles.

Statistical Analyses

To examine the differences in baseline clinical or demographic characteristics between PD patients with normal CSF Aβ and those with low CSF Aβ, we used the Kruskal-Wallis One-way Analysis of Variance for non-normally distributed continuous variables or chi-square for categorical variables. Normality was determined by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In the primary analysis, we ran linear mixed effects regression analysis on the three PD groups. The first group included all 379 PD participants with baseline CSF Aβ and APOE ε4; the second group included the 103 PD with low baseline CSF Aβ; and the third group included the 276 PD participants with normal CSF Aβ. The linear mixed effects model includes APOE ε4, time, and APOE ε4 × time as the independent variables of primary interest, with age, gender and education as potential confounding variables. We selected age and gender because these variables (along with disease duration) are the most commonly reported predictors of PD cognitive decline and dementia (18, 19, 21, 22). Baseline disease duration was similar in all PPMI participants (36, 49), thus not included as a separate covariate. We included education as the final variable because of the known impact of cognitive testing. The random intercept is included to account for within person correlations. For each group, we estimated the annual rate of change in cognitive scores for the primary cognitive outcome measure (MoCA) and the secondary cognitive outcome measures [HVLT-R (Immediate Recall, Delayed Recall, Recognition Discrimination Index), SDMT, Letter Number Sequencing, Semantic verbal Fluency Test, and Judgement of Line Orientation] by the regression coefficients of time and APOE ε4 × time. In the mixed effects regression analysis for all PD participants, i.e. the first group, we also included low/normal CSF Aβ and CSF Aβ χ time as independent variables to examine the effect of CSF Aβ on baseline cognitive outcome measures and their annual change rate. Analyses were performed using R v3.0 (The R foundation of Statistical Computing) and SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0). In all statistical analyses, two-tailed p values were used; those values of p < 0.05 were deemed as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

See Table 1 for complete group baseline characteristics. There were 215 participants in the normal CSF Aβ APOE ε4− group, 61 participants in the normal CSF Aβ APOE ε4+ group, 64 participants in the low CSF Aβ APOE ε4− group, and 39 participants in the low CSF Aβ APOE ε4+ group (χ2=9.595, p=0.002). The Kruskal-Wallis Test revealed significant differences between groups in age (p=0.007) and MDS-UPDRS III (p=0.048) but showed no other significant differences in baseline demographic characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics. Table depicts the median and interquartile range for the demographic and cognitive data at baseline, with p values computed using Kruskal-Wallis One-way Analysis of Variance, or *χ2 test as appropriate.

| Characteristic | Normal CSF Aβ APOE ε4− (N=215) |

Normal CSF Aβ APOE ε4+ (N=61) |

Low CSF Aβ APOE ε4− (N=64) |

Low CSF Aβ APOE ε4+ (N=39) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) Median [Interquartile Range] |

62.0 [55.0-68.0] |

57.0 [51.0-66.0] |

65.0 [57.3-70.0] |

64.0 [58.0-70.0] |

0.007Λ |

| Female* N (%) |

80 (37%) |

18 (30%) |

18 (28%) |

10 (26%) |

0.298 |

| Education (years) Median [Interquartile Range] |

16.0 [14.0-18.0] |

16.0 [14.0-18.0] |

16.0 [14.0-17.8] |

16.0 [14.0-18.0] |

0.982 |

| MDS-UPDRS III Median [Interquartile Range] |

18.0 [12.0-24.0] |

17.0 [11.0-25.0] |

19.5 [16.0-28.0] |

20.5 [16.0-27.3] |

0.048 |

| Hoehn & Yahr Median [Interquartile Range] |

2.0 [1.0-2.0] |

1.0 [1.0-2.0] |

2.0 [1.0-2.0] |

2.0 [1.0-2.0] |

0.335 |

| MoCA Total Median [Interquartile Range] |

28.0 [26.0-29.0] |

28.0 [26.0-29.0] |

27.0 [26.0-28.8] |

28.0 [26.0-29.0] |

0.669 |

| HVLT-R Immediate Recall Median [Interquartile Range] |

25.0 [21.0-28.0] |

25.0 [22.0-30.0] |

25.0 [21.0-27.0] |

23.0 [17.0-26.0] |

0.053† |

| HVLT-R Delayed Recall Median [Interquartile Range] |

9.0 [7.0-10.0] |

9.0 [7.0-10.0] |

9.0 [7.0-10.0] |

8.0 [5.0-10.0] |

0.170 |

| HVLT-R Recognition Discrimination Index Median [Interquartile Range] |

7.0 [5.0-10.0] |

8.0 [6.0-10.0] |

7.0 [4.3-9.0] |

7.0 [4.0-9.0] |

0.186 |

| SFT Median [Interquartile Range] |

48.0 [42.0-56.0] |

52.0 [43.0-58.0] |

47.0 [40.0-53.0] |

46.0 [36.0-52.5] |

0.070 |

| JLO Median [Interquartile Range] |

13.0 [12.0-15.0] |

13.0 [12.0-14.0] |

14.0 [12.0-14.0] |

13.0 [10.0-14.0] |

0.649 |

| LNS Median [Interquartile Range] |

11.0 [9.0-12.0] |

11.0 [9.0-13.0] |

11.0 [9.0-12.0] |

10.0 [8.0-12.0] |

0.187 |

| SDMT Median [Interquartile Range] |

43.0 [35.0-48.0] |

43.0 [37.0-49.0] |

40.0 [32.0-46.0] |

40.0 [28.0-46.0] |

0.025‡ |

p≤0.05 by post-hoc testing between Normal CSF Aβ APOE ε4+ and Low CSF Aβ APOE ε4− and between Normal CSF Aβ APOE ε4+ and Low CSF Aβ APOE ε4+

p≤0.05 by post-hoc testing between Normal CSF Aβ APOE ε4+ and Low CSF Aβ APOE ε4+

p≤0.05 by post-hoc testing between Normal CSF Aβ APOE ε4+ and Low CSF Aβ APOE ε4−

APOE = Apolipoprotein E; APOE ε4+ = presence of at least one APOE ε4 allele; APOE ε4− = absence of APOE ε4 allele; MDS-EPDRS = Movement Disorders Society United Parkinson’s disease Rating Scale; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; HVLT-R = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised; SFT = Semantic verbal Fluency Test; JLO = Benton Judgement of Line Orientation; LNS = Letter-Number Sequencing; SDMT = Symbol Digit Modalities Test.

Effect of CSF Aβ on Cognitive Decline

Results from the linear mixed effects regression analysis on the full group of 379 PD participants can be found in Table 2. In this group, those who were male, older, and had fewer years of education showed lower baseline scores on all cognitive tests (all p<0.05), except Judgement of Line Orientation where female participants had lower baseline score (p<0.001), and Letter-Number Sequencing where there was no gender difference.

Table 2:

Effect of Predictor Variables on Cognitive Assessments in the full PD group. Table depicts the beta estimate, confidence intervals, and p-values of the predictor variables (Time, APOE ε4, APOE ε4 × time, CSF Aβ, CSF Aβ × time) and control variables (Age, Education, Gender) on cognitive assessments in the full PD group. R2 for the fixed effects is shown, since this reflects the proportion of the variations explained by the observed covariates.

| Cognitive Assessment | R2 | Predictor Variable | Beta Estimate | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| MoCA Total | 0.09 | |||||

| Education | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.039 | ||

| Female | 0.57 | 0.13 | 1.01 | 0.012 | ||

| Age | −0.07 | −0.09 | −0.05 | <0.001 | ||

| Time | −0.02 | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.729 | ||

| APOE ε4 | 0.05 | −0.44 | 0.53 | 0.854 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.17 | −0.33 | −0.02 | 0.032 | ||

| CSF Aβ | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.990 | ||

| CSF Aβ × time | −0.25 | −0.41 | −0.09 | 0.002 | ||

| SDMT | 0.24 | |||||

| Education | 0.51 | 0.24 | 0.78 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 3.06 | 1.39 | 4.72 | <0.001 | ||

| Age | −0.44 | −0.52 | −0.36 | <0.001 | ||

| Time | −0.28 | −0.54 | −0.02 | 0.036 | ||

| APOE ε4 | 0.08 | −1.76 | 1.91 | 0.937 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.39 | −0.86 | 0.09 | 0.110 | ||

| CSF Aβ | −1.62 | −3.44 | 0.21 | 0.083 | ||

| CSF Aβ × time | −0.91 | −1.37 | −0.45 | <0.001 | ||

| HVLT-R Immediate Recall | 0.17 | |||||

| Education | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.43 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 2.07 | 1.20 | 2.93 | <0.001 | ||

| Age | −0.19 | −0.23 | −0.15 | <0.001 | ||

| Time | 0.02 | −0.12 | 0.16 | 0.783 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −0.11 | −1.07 | 0.86 | 0.824 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.02 | −0.27 | 0.23 | 0.872 | ||

| CSF Aβ | −0.24 | −1.20 | 0.72 | 0.620 | ||

| CSF Aβ × time | −0.20 | −0.44 | 0.05 | 0.113 | ||

| HVLT-R Delayed Recall | 0.17 | |||||

| Education | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.22 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 1.00 | 0.55 | 1.44 | <0.001 | ||

| Age | −0.09 | −0.12 | −0.07 | <0.001 | ||

| Time | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.12 | 0.171 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −0.09 | −0.60 | 0.42 | 0.727 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.03 | −0.16 | 0.10 | 0.698 | ||

| CSF Aβ | −0.12 | −0.62 | 0.38 | 0.646 | ||

| CSF Aβ × time | −0.20 | −0.32 | −0.07 | 0.003 | ||

| HVLT-R Recognition Discrimination Index | 0.16 | |||||

| Education | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.001 | ||

| Female | 1.26 | 0.72 | 1.81 | <0.001 | ||

| Age | −0.11 | −0.13 | −0.08 | <0.001 | ||

| Time | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.26 | <0.001 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −0.12 | −0.75 | 0.51 | 0.712 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.998 | ||

| CSF Aβ | −0.28 | −0.91 | 0.35 | 0.380 | ||

| CSF Aβ × time | −0.18 | −0.33 | −0.03 | 0.020 | ||

| LNS | 0.15 | |||||

| Education | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.22 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | −0.01 | −0.47 | 0.45 | 0.966 | ||

| Age | −0.10 | −0.12 | −0.08 | <0.001 | ||

| Time | −0.08 | −0.14 | −0.01 | 0.025 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −0.10 | −0.62 | 0.41 | 0.695 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.09 | −0.21 | 0.04 | 0.165 | ||

| CSF Aβ | −0.16 | −0.67 | 0.36 | 0.550 | ||

| CSF Aβ × time | −0.13 | −0.25 | −0.01 | 0.032 | ||

| SFT | 0.20 | |||||

| Education | 0.70 | 0.37 | 1.02 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 5.79 | 3.76 | 7.82 | <0.001 | ||

| Age | −0.36 | −0.46 | −0.26 | <0.001 | ||

| Time | −0.09 | −0.34 | 0.16 | 0.472 | ||

| APOE ε4 | 0.93 | −1.39 | 3.25 | 0.431 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.29 | −0.75 | 0.16 | 0.211 | ||

| CSF Aβ | −1.65 | −3.95 | 0.65 | 0.161 | ||

| CSF Aβ × time | −0.45 | −0.89 | 0.00 | 0.051 | ||

| JLO | 0.12 | |||||

| Education | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.19 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | −1.18 | −1.55 | −0.81 | <0.001 | ||

| Age | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.03 | <0.001 | ||

| Time | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.445 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −0.35 | −0.78 | 0.09 | 0.122 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.05 | −0.14 | 0.05 | 0.337 | ||

| CSF Aβ | −0.14 | −0.58 | 0.29 | 0.521 | ||

| CSF Aβ × time | −0.06 | −0.15 | 0.04 | 0.225 | ||

APOE = Apolipoprotein E; CSF Aβ = Cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid Beta; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; HVLT-R = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised; SFT = Semantic verbal Fluency Test; JLO = Benton Judgement of Line Orientation; LNS = Letter-Number Sequencing; SDMT = Symbol Digit Modalities Test; CI = Confidence Interval.

Participants with PD declined by 0.28 points annually on the SDMT (95%CI: 0.02-0.54), by 0.08 points annually on the Letter-Number Sequencing (95%CI: 0.01-0.14), and improved by 0.17 points annually on the HVLT-R Recognition Discrimination Index (95%CI: 0.08-0.26). No other cognitive tests declined or improved in the lull PD group over the 5 years.

Participants with PD with low CSF Aβ at baseline had a faster rate of decline than those with normal CSF Aβ on all cognitive tests, except the Judgement of Line Orientation and HVLT-R Immediate Recall (see Table 2 for details). Participants with PD who were APOE ε4+ had a faster rate of decline than APOE ε4− by 0.17 points annually on the MoCA (95%CI: −0.02-0.33, standardized 5-year effect size 0.37). No other cognitive tests showed a significant effect of APOE ε4 on the annual change rate in the full PD group.

Effect APOE ε4 on Cognitive Decline in PD with Low CSF Aβ

Results from the linear mixed effects regression analysis on the 103 PD participants with low CSF Aβ at baseline can be found in Table 3. In this group, all cognitive tests were lower in those who were older (all p<0.05), but only HVLT-R Delayed Recall was lower in those with fewer years of education (p=0.019). MoCA (p=0.014), HVLT-R Delayed Recall (p=0.016), and HVLT-R Recognition Discrimination Index (p=0.041) were lower in male PD participants with low CSF Aβ, while Judgement of Line Orientation (p=0.003) was lower in female PD participants. The APOE ε4+ and APOE ε4− groups did not differ in any baseline cognitive tests.

Table 3:

Effect of Predictor Variables on Cognitive Assessments in PD patients with low CSF Aβ at baseline. Table depicts the beta estimate, confidence intervals, and p-values of the predictor variables (APOE ε4, Time, and APOE ε4 × time) and control variables (Age, Education, Gender) on cognitive assessments in the low CSF Aβ group. R2 for the fixed effects shown, since this reflects the proportion of the variations explained by the observed covariates.

| Cognitive Assessment | R2 | Predictor Variable | Beta Estimate | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| MoCA Total | 0.12 | |||||

| Education | 0.05 | −0.10 | 0.12 | 0.526 | ||

| Female | 1.28 | 0.26 | 2.31 | 0.014 | ||

| Age | −0.07 | −0.12 | −0.02 | 0.004 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −0.01 | −0.94 | 0.92 | 0.983 | ||

| Time | −0.16 | −0.39 | 0.07 | 0.164 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.57 | −0.97 | −0.17 | 0.005 | ||

| SDMT | 0.24 | |||||

| Education | 0.35 | −0.22 | 0.92 | 0.231 | ||

| Female | 3.39 | −0.57 | 7.33 | 0.093 | ||

| Age | −0.53 | −0.72 | −0.33 | <0.001 | ||

| APOE ε4 | 0.72 | −2.91 | 4.35 | 0.699 | ||

| Time | −0.87 | −1.38 | −0.36 | 0.001 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −1.40 | −2.29 | −0.50 | 0.002 | ||

| HVLT-R Immediate Recall | 0.19 | |||||

| Education | 0.21 | −0.08 | 0.50 | 0.152 | ||

| Female | 1.77 | −0.21 | 3.75 | 0.079 | ||

| Age | −0.24 | −0.34 | −0.14 | <0.001 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −1.09 | −2.90 | 0.72 | 0.237 | ||

| Time | −0.08 | −0.34 | 0.18 | 0.552 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.34 | −0.81 | 0.12 | 0.147 | ||

| HVLT-R Delayed Recall | 0.21 | |||||

| Education | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.019 | ||

| Female | 1.29 | 0.24 | 2.34 | 0.016 | ||

| Age | −0.12 | −0.17 | −0.07 | <0.001 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −0.78 | −1.73 | 0.17 | 0.107 | ||

| Time | −0.10 | −0.23 | 0.04 | 0.173 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.23 | −0.48 | 0.01 | 0.058 | ||

| HVLT-R Recognition Discrimination Index | 0.17 | |||||

| Education | 0.12 | −0.07 | 0.31 | 0.226 | ||

| Female | 1.39 | 0.06 | 2.73 | 0.041 | ||

| Age | −0.14 | −0.20 | −0.07 | <0.001 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −0.69 | −1.90 | 0.53 | 0.267 | ||

| Time | 0.05 | −0.14 | 0.20 | 0.582 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.23 | −0.51 | 0.06 | 0.117 | ||

| LNS | 0.13 | |||||

| Education | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.20 | 0.310 | ||

| Female | 0.40 | −0.52 | 1.31 | 0.395 | ||

| Age | −0.09 | −0.14 | −0.05 | <0.001 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −0.57 | −1.41 | 0.27 | 0.184 | ||

| Time | −0.23 | −0.38 | −0.08 | 0.002 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.04 | −0.30 | 0.21 | 0.740 | ||

| SFT | 0.16 | |||||

| Education | 0.08 | −0.57 | 0.72 | 0.815 | ||

| Female | 2.44 | −1.98 | 6.87 | 0.279 | ||

| Age | −0.48 | −0.70 | −0.26 | <0.001 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −0.12 | −4.27 | 4.02 | 0.953 | ||

| Time | −0.50 | −0.94 | −0.07 | 0.023 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.44 | −1.20 | 0.33 | 0.261 | ||

| JLO | 0.11 | |||||

| Education | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.16 | 0.563 | ||

| Female | −1.33 | −2.20 | −0.46 | 0.003 | ||

| Age | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.02 | 0.007 | ||

| APOE ε4 | −0.60 | −1.47 | 0.28 | 0.180 | ||

| Time | −0.06 | −0.17 | 0.05 | 0.284 | ||

| APOE ε4 × time | −0.11 | −0.30 | 0.08 | 0.258 | ||

APOE = Apolipoprotein E; CSF Aβ = Cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid Beta; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; HVLT-R = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised; SFT = Semantic verbal Fluency Test; JLO = Benton Judgement of Line Orientation; LNS = Letter-Number Sequencing; SDMT = Symbol Digit Modalities Test; CI = Confidence Interval.

In PD participants with low CSF Aβ, the APOE ε4+ group had a faster rate of decline than the APOE ε4− group on the MoCA by 0.57 points annually (95% CI: 0.17-0.97, standardized 5-year effect size 1.2). The APOE ε4+ group also had a faster rate of decline on the SDMT by 1.40 points annually (95% CI: 0.50-2.29, standardized 5-year effect size 0.72) (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

(A) MoCA and (B) SDMT scores over time. Graph illustrates greater cognitive decline in low CSF Aβ APOE ε4+ compared to low CSF Aβ APOE ε4− and normal CSF Aβ groups.

MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SDMT = Symbol Digit Modalities Test; CSF Aβ = Cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid Beta; APOE = Apolipoprotein E; APOE ε4+ = presence of at least one APOE ε4 allele; APOE ε4− = absence of APOE ε4 allele.

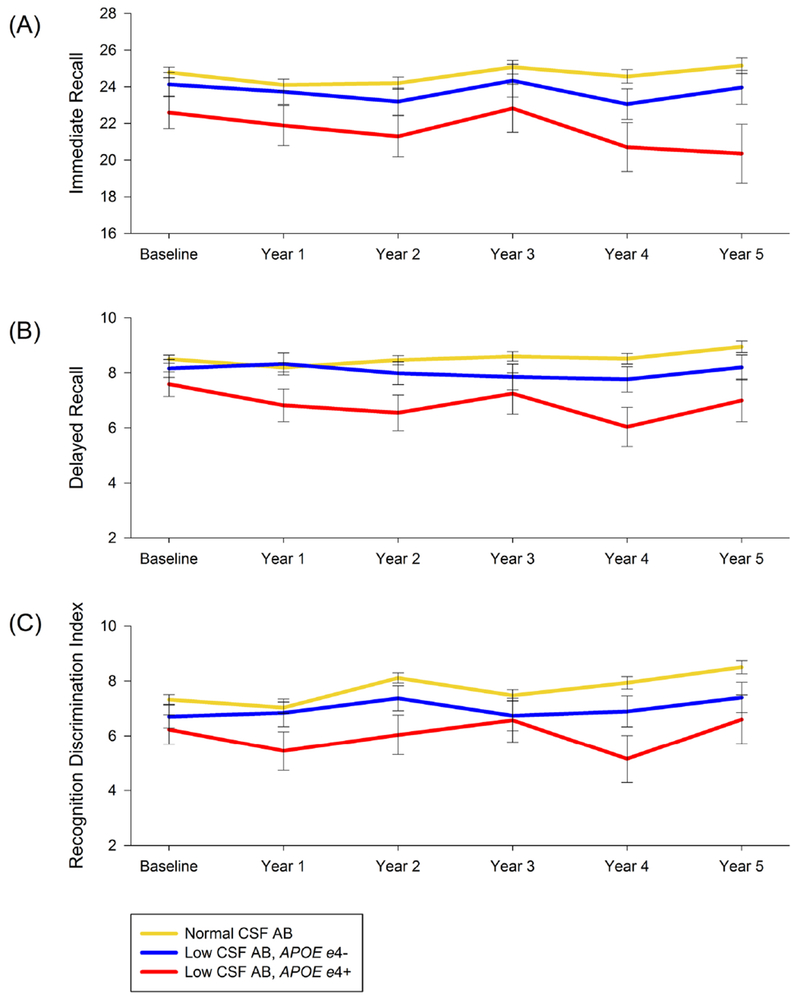

The APOE ε4+ group showed a trend toward faster rate of decline than the APOE ε4− group on HVLT-R Delayed Recall (95% CI: −0.01-0.48, standardized 5-year effect size 0.23), but not on HVLT-R Immediate Recall or Recognition Discrimination Index (Figure 3). There was no difference in rate of decline between APOE ε4 groups on the Letter-Number Sequencing, Semantic verbal Fluency Test, or Judgement of Line Orientation (Supplemental Figure).

Figure 3:

HVLT-R (A) Immediate Recall (B) Delayed Recall, and (C) Recognition Discrimination Index over time.

HVLT-R = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised; CSF Aβ = Cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid Beta; APOE = Apolipoprotein E; APOE ε4+ = presence of at least one APOE ε4 allele; APOE ε4− = absence of APOE ε4 allele.

Effect of APOE ε4 on Cognitive Decline in PD with Normal CSF Aβ

Results from the linear mixed effects regression analysis on the 276 PD participants with normal CSF Aβ at baseline can be found in Supplemental Table 1. In this group, those who were male, older, and had fewer years of education showed lower baseline scores on all cognitive tests (all p<0.05), except Judgement of Line Orientation where female participants had lower baseline score (p<0.001), and Letter-Number Sequencing where there was no difference between genders.

PD participants declined by 0.38 points annually on the SDMT (95%CI: 0.12-0.64), by 0.07 points annually on the Letter-Number Sequencing (95%CI: 0.01-0.14), and improved by 0.16 points annually on the HVLT-R Recognition Discrimination Index (95%CI: 0.07-0.24). No other cognitive tests declined or improved in the PD participants with normal CSF Aβ over the 5 years (see Supplemental Table 1 for details). The APOE ε4+ and APOE ε4− groups did not differ in baseline scores and did not differ on the rate of decline on any cognitive tests. See Supplemental Table 2 for mean cognitive scores for all groups over time.

DISCUSSION

Several longitudinal studies have shown that patients with PD and low CSF Aβ-42 have an increased risk of developing cognitive decline and dementia (23). In this study, we extended these findings to show that patients with PD, who have low CSF Aβ in addition to at least one APOE ε4 allele have the highest rate of global cognitive decline over the first five years after diagnosis. These patients also experienced faster declines in processing speed as compared to PD patients without the APOE ε4allele. By contrast, in PD patients with normal CSF Aβ, having at least one APOE ε4 allele was not associated with early cognitive change. These results suggest that in PD patients an APOE ε4 genotype and Aβ might interact to promote cognitive changes early in the disease.

Consistent with prior studies in the PPMI cohort (4, 50), we found that PD participants with lower CSF Aβ at baseline showed faster cognitive decline over 5 years on almost all cognitive tests. Prior studies have identified CSF Aβ as a predictor of cognitive impairment (29) and future decline (51, 52) in early, de novo PD. Studies have also shown the APOE ε4 genotype increases the risk of dementia in PD at end of life (31, 33, 53). However, the association between cognitive impairment and APOE ε4 is inconsistent when studies included earlier, more mildly impaired PD patients. For instance, the ICICLE-PD study did not find a higher rate of baseline cognitive impairment in the newly diagnosed PD patients with an APOE ε4 allele (29), although this study showed APOE ε4+ PD patients had decreased brain activation on fMRI during memory encoding. Our study agrees with the ICICLE-PD study, in that APOE ε4 is not associated with having cognitive impairment at baseline in the lull PD group or in those with low or normal CSF Aβ. However, we found global cognitive decline after baseline, as assessed on the MoCA, in the PPMI PD participants over 5 years. Further, when we separated PD participants by CSF Aβ, the APOE ε4-associated decline on the MoCA was only present in those with low baseline CSF Aβ, and here the decline is large. This finding strongly suggests that the combination of low CSF Aβ and APOE ε4 is an important predictor of impending global cognitive decline in PD. It also suggests that the effects of APOE ε4 genotype on early cognitive decline might be detectable in specific PD subgroups, but not in others (34).

Beyond prediction, these biomarkers may reveal critical information about the biology underlying differing rates of cognitive progression that is observed in PD patients. For instance, concomitant Alzheimer’s disease pathology, defined by tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles and Aβ-positive plaques, could explain our findings. APOE ε4 is a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s pathology, and one recent large autopsy series found that PD patients with Alzheimer’s co-pathology had a greater rate of cognitive decline on the Mini-Mental State Examination during the 10 years prior to death compared to PD patients with a pure synucleinopathy (54). Therefore, in the PPMI cohort, Alzheimer’s co-pathology could already be present in some patients at the time of motor onset, which may influence the rate of early cognitive decline. However, if this were the sole explanation, we might expect a more pronounced association with episodic memory, as is commonly seen in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Longitudinal cognitive analyses with diagnostic confirmation at autopsy are part of the PPMI protocol. Postmortem findings will eventually elucidate whether low CSF Aβ at PD diagnosis is indicative of co-morbid Alzheimer’s pathology.

There are likely other factors that contribute to why PD patients with an APOE ε4 allele and low CSF Aβ show a faster rate of cognitive decline. While the APOE ε4 genotype is linked to dementia due to its direct effect on Alzheimer’s co-pathology, it is possible that it increases risk through additional, independent mechanisms. For example, in PD patients with no or low levels of Alzheimer’s co-pathology (i.e. low burden of tau neurofibrillary tangles), the APOE ε4 genotype still confers an increased risk of dementia (33) and increased severity of Lewy-body pathology (55). The PPMI cohort consists of newly diagnosed PD patients. Thus, based on the Braak and Braak hypothesis, Lewy-body pathology is most likely limited to the brainstem, amygdala, or limbic regions, (56) and not yet spread to the neocortex. Autopsy studies showed that the APOE ε4 genotype is associated with Alzheimer’s co-pathologies in PD patients with neocortical Lewy-bodies but not patients with Lewy-bodies limited to the brainstem, limbic regions, or amygdala (54). It is unclear how APOE influences biology in pure synucleinopathies, but APOE is a crucial element in the lipoprotein metabolism (57), lipid transportation (58), and clearance of amyloid proteins in the brain (59). One study in transgenic mice showed that α-synuclein-induced neurodegeneration involves activation of the ubiquitin/proteasome system with a massive increase in apolipoprotein E levels and accumulation of insoluble mouse Aβ (60). Other studies suggest Aβ, along with other protein aggregates, can be induced by α-synuclein pathology (61, 62). Distinguishing the individual contributions of these proteins to clinical symptoms is critical, as trials targeting α-synuclein, Aβ, and tau are all currently underway.

Prior genotype-phenotype studies also show that the APOE ε4 genotype is specifically associated with poor episodic memory and semantic verbal fluency in PD patients (31). While we found a trend toward worsening episodic memory with delayed recall in the low C SF Aβ and APOE ε4+ group, these patients primarily showed a more pronounced decline on global cognitive measures and processing speed. Indeed, we found the MoCA to be the most robust measure, with PD participants who had low CSF Aβ and at least one APOE ε4 allele showing an annual decline of over half a point faster than those with no APOE ε4 allele. This adds to the growing literature supporting the MoCA as a sensitive test of global cognition in early PD patients (38, 63, 64). In addition, we found the SDMT, a test of attention and processing speed, to decline faster in PD patients with low CSF Aβ and at least one APOE ε4. A recent large study (n=1741, NET-PD) showed the SDMT declined by 0.21 annually in the total PD cohort over six years (21), which is similar to the rate of change seen in our total PD group (decline by 0.28/year). The group with low CSF Aβ declined by 0.87/year, whereas those with low CSF Aβ and at least one APOE ε4 allele declined by 1.40/year. These findings are unsurprising given that reduced processing speed is considered a general proxy for hastened brain aging (65) and both increased amyloid burden and the presence of an APOE ε4 allele have been previously associated with longitudinal decline in processing speed in cognitively normal older adults (66, 67). In PD, poorer performance on processing speed measures is associated with progression to dementia (22). Although reduced processing speed is ubiquitous in PD and generally attributed to dopaminergic deficits in fronto-striatal pathways, our results suggest that a faster rate of decline in processing speed may result from additional underlying factors related to APOE ε4 and Aβ.

The varying rate of cognitive decline in PD patients is a major impediment to clinical trial development. For therapeutics aimed at disease modification, the ideal patient population is one that is cognitively normal but at high likelihood to progress to cognitive impairment during the typical course of a clinical trial. Predictive models of imminent cognitive decline are thus necessary for such trial design. Currently, the most commonly reported predictors for PD-associated cognitive decline are older age and longer duration of motor symptoms (2, 18–20). However, older patients are commonly excluded from clinical trials given the increased risk of co-morbidities, such as diabetes, cancer, or stroke. Whereas male gender has also been associated with faster cognitive decline (22), gender alone is not a reasonable inclusion criterion for a clinical trial given the obvious lack of generalizability. By contrast, biomarkers such as CSF protein analysis and genetic data could be considered as screening tools.

This study has important strengths. The study is rooted in the de novo PPMI cohort. Disease duration is similar in all PPMI participants, thus reducing variability in one of the strongest predictors of cognitive impairment in PD patients. Other major predictors of PD cognitive decline, such as age and gender, are similar across the study groups. When we added other potential confounders to the models in an exploratory analysis (REM Sleep score, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, starting PD medications, and gender × time) all of the significant predictors in Tables 2, 3 and Supplemental Table 1 were still significant with similar Beta Estimates. A further strength is that all of the CSF assays were performed by the same lab using standardized techniques. A major challenge to this study is that the optimal cutoff for ‘low’ CSF in PD patients is not known. There is large interassay variability and inconsistency of CSF Aβ measurements, even among different centers using the same assays. Therefore, we choose the PPMI healthy control group values to determine our cutoff for the low CSF Aβ group. Even with this fairly conservative estimate, our low CSF Aβ group, compared to our normal CSF Aβ group, shows similar cognitive progression as other studies investigating the risk of cognitive decline in PD patients with abnormal Aβ (4, 23).

CONCLUSIONS

Post-mortem studies show that APOE ε4 genotype increases risk for end of life dementia in PD patients, both in patients with and without co-morbid Alzheimer’s pathology (33). Our study investigated the APOE ε4 genotype as predictive of early cognitive decline in newly diagnosed PD. We found that early PD APOE ε4 carriers, who also have abnormal CSF Aβ at diagnosis, are at the highest risk for global cognitive decline in the first five years of disease, whereas PD APOE ε4 carriers with normal CSF Aβ do not differ from non-ε4 carriers. Therefore, the combination of APOE ε4 genotype and abnormal CSF Aβ should be considered when developing predictive models of cognitive decline in early PD patients.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure: (A) Letter-Number Sequencing (B) Semantic verbal Fluency Test (Animals, Vegetables, and Fruits named), and (C) Judgement of Line Orientation over time.

CSF Aβ = Cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid Beta; APOE = Apolipoprotein E; APOE ε4+ = presence of at least one APOE ε4 allele; APOE ε4− = absence of APOE ε4 allele LNS = Letter-Number Sequencing; SFT = Semantic Fluency Test; JLO = Judgement of Line Orientation; CSF Aβ = Cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid Beta; APOE = Apolipoprotein E; APOE ε4+ = presence of at least one APOE ε4 allele; APOE ε4− = absence of APOE ε4 allele

HIGHLIGHTS.

Parkinson’s disease patients vary in the rate of cognitive decline after diagnosis

Fastest cognitive decline is in those with both low CSF Aβ and the APOEε4 genotype

Global cognition and processing speed are the most sensitive measures of decline

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the NIH/NIA (AG047366), NIH/NINDS (NS075097, NS062684) and Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s disease Research. The funding source(s) did not have any involvement in the analysis or interpretation of the data nor in the writing of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- HC

Healthy controls

- HVLT-R

Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PPMI

Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative

- SDMT

Symbol Digit Modalities Test

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Levy G, Tang MX, Louis ED, Cote LJ, Alfaro B, Mejia H, et al. The association of incident dementia with mortality in PD. Neurology. 2002;59(11):1708–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hely MA, Morris JG, Reid WG, Trafficante R. Sydney Multicenter Study of Parkinson’s disease: non-L-dopa-responsive problems dominate at 15 years. Mov Disord. 2005;20(2):190–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hely MA, Reid WG, Adena MA, Halliday GM, Morris JG. The Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson’s disease: the inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov Disord. 2008;23(6):837–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terrelonge M Jr, Marder KS, Weintraub D, Alcalay RN. CSF beta-Amyloid 1-42 Predicts Progression to Cognitive Impairment in Newly Diagnosed Parkinson Disease. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN. 2016;58(1):88–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aarsland D, Bronnick K, Larsen JP, Tysnes OB, Alves G, For the Norwegian ParkWest Study Group. Cognitive impairment in incident, untreated Parkinson disease: The Norwegian ParkWest Study. Neurology. 2009;72(13):1121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foltynie T, Brayne CE, Robbins TW, Barker RA. The cognitive ability of an incident cohort of Parkinson’s patients in the UK. The CamPaIGN study. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 3):550–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broeders M, de Bie RM, Velseboer DC, Speelman JD, Muslimovic D, Schmand B. Evolution of mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2013;81(4):346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janvin CC, Larsen JP, Aarsland D, Hugdahl K. Subtypes of mild cognitive impairment in parkinson’s disease: Progression to dementia. Movement Disorders. 2006;21(9):1343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olanow CW, Schapira AH. Therapeutic prospects for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(3):337–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svenningsson P, Westman E, Ballard C, Aarsland D. Cognitive impairment in patients with Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis, biomarkers, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(8):697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marder K Cognitive impairment and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25 Suppl 1:S110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong MJ, Gruber-Baldini AL, Reich SG, Fishman PS, Lachner C, Shulman LM. Which features of Parkinson’s disease predict earlier exit from the workforce? Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(11):1257–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burn D, Weintraub D, Ravina B, Litvan I. Cognition in movement disorders: where can we hope to be in ten years? Mov Disord. 2014;29(5):704–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barone P, Antonini A, Colosimo C, Marconi R, Morgante L, Avarello TP, et al. The PRIAMO study: A multicenter assessment of nonmotor symptoms and their impact on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24(11):1641–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Kurtis MM, Chaudhuri KR, Group NV. The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26(3):399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Lau LM, Verbaan D, Marinus J, van Hilten JJ. Survival in Parkinson’s disease. Relation with motor and non-motor features. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(6):613–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kowal SL, Dall TM, Chakrabarti R, Storm MV, Jain A. The current and projected economic burden of Parkinson’s disease in the United States. Mov Disord. 2013;28(3):311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cholerton BA, Zabetian CP, Quinn JF, Chung KA, Peterson A, Espay AJ, et al. Pacific Northwest Udall Center of excellence clinical consortium: study design and baseline cohort characteristics. Journal of Parkinson’s disease. 2013;3(2):205–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reid WG, Hely MA, Morris JG, Loy C, Halliday GM. Dementia in Parkinson’s disease: a 20-year neuropsychological study (Sydney Multicentre Study). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(9):1033–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chahine LM, Weintraub D, Hawkins KA, Siderowf A, Eberly S, Oakes D, et al. Cognition in individuals at risk for Parkinson’s: Parkinson associated risk syndrome (PARS) study findings. Movement Disorders. 2016;31(l):86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wills AA, Elm JJ, Ye R, Chou KL, Parashos SA, Hauser RA, et al. Cognitive function in 1736 participants in NINDS Exploratory Trials in PD Long-term Study-1. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;33:127–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cholerton B, Johnson CO, Fish B, Quinn JF, Chung KA, Peterson-Hiller AL, et al. Sex differences in progression to mild cognitive impairment and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leaver K, Poston KL. Do CSF Biomarkers Predict Progression to Cognitive Impairment in Parkinson’s disease patients? A Systematic Review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2015;25(4):411–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrou M, Dwamena BA, Foerster BR, MacEachem MP, Bohnen NI, Muller ML, et al. Amyloid deposition in Parkinson’s disease and cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Mov Disord. 2015;30(7):928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beyer MK, Alves G, Hwang KS, Babakchanian S, Bronnick KS, Chou YY, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid Abeta levels correlate with structural brain changes in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2013;28(3):302–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu SY, Zuo LJ, Wang F, Chen ZJ, Hu Y, Wang YJ, et al. Potential biomarkers relating pathological proteins, neuroinflammatory factors and free radicals in PD patients with cognitive impairment: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol. 2014; 14:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stav AL, Aarsland D, Johansen KK, Hessen E, Aiming E, Fladby T. Amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and cognition in early Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21(7):758–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldman JG, Andrews H, Amara A, Naito A, Alcalay RN, Shaw LM, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid, plasma, and saliva in the BioFIND study: Relationships among biomarkers and Parkinson’s disease Features. Mov Disord. 2018;33(2):282–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamall AJ, Breen DP, Duncan GW, Khoo TK, Coleman SY, Firbank MJ, et al. Characterizing mild cognitive impairment in incident Parkinson disease: the ICICLE-PD study. Neurology. 2014;82(4):308–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montine TJ, Shi M, Quinn JF, Peskind ER, Craft S, Ginghina C, et al. CSF Aβ42 and tau in Parkinson’s disease with cognitive impairment. Movement Disorders. 2010;25(15):2682–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mata IF, Leverenz JB, Weintraub D, Trojanowski JQ, Hurtig H, VanDeerlin V, et al. APoe, mapt, and snca genes and cognitive performance in parkinson disease. JAMA neurology. 2014;71(11):1405–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arai H, Muramatsu T, Higuchi S, Sasaki H, Trojanowski J. Apolipoprotein Egene in Parkinson’s disease with or without dementia. The Lancet. 1994;344(8926):889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuang D, Leverenz JB, Lopez OL, Hamilton RL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA, et al. APOE epsilon4 increases risk for dementia in pure synucleinopathies. JAMA neurology. 2013;70(2):223–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mengel D, Dams J, Ziemek J, Becker J, Balzer-Geldsetzer M, Hilker R, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 does not affect cognitive performance in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;29:112–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parkinson Progression Marker I. The Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI). Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95(4):629–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marek K, Chowdhury S, Siderowf A, Lasch S, Coffey CS, Caspell-Garcia C, et al. The Parkinson’s progression markers initiative (PPMI) - establishing a PD biomarker cohort. Annals of clinical and translational neurology. 2018;5(12):1460–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gill DJ, Freshman A, Blender JA, Ravina B. The Montreal cognitive assessment as a screening tool for cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(7):1043–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hendershott TR, Zhu D, Llanes S, Poston KL. Domain-specific accuracy of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment subsections in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;38:31–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dalrymple-Alford JC, MacAskill MR, Nakas CT, Livingston L, Graham C, Crucian GP, et al. The MoCA: well-suited screen for cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;75(19):1717–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vanderploeg RD, Schinka JA, Jones T, Small BJ, Graves AB, Mortimer JA. Elderly norms for the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised. Clin Neuropsychol. 2000;14(3):318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith A Symbol Digit Modalities Test Manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strauss E, Sherman E, Spreen O. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary (3rd Ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wechsler D Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Third Edition Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tombaugh TN, Kozak J, Rees L. Normative data stratified by age and education for two measures of verbal fluency: FAS and animal naming. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1999;14(2):167–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benton A Contributions to Neuropsychological Assessment: A Clinical Manual (2nd. Ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang JH, Irwin DJ, Chen-Plotkin AS, Siderowf A, Caspell C, Coffey CS, et al. Association of cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid 1-42, T-tau, P-tau181, and alpha-synuclein levels with clinical features of drug-naive patients with early Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(10):1277–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang JH, Mollenhauer B, Coffey CS, Toledo JB, Weintraub D, Galasko DR, et al. CSF biomarkers associated with disease heterogeneity in early Parkinson’s disease: the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative study. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):935–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nalls MA, Keller MF, Hernandez DG, Chen L, Stone DJ, Singleton AB, et al. Baseline genetic associations in the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI). Mov Disord. 2016;31(1):79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simuni T, Siderowf A, Lasch S, Coffey CS, Caspell-Garcia C, Jennings D, et al. Longitudinal Change of Clinical and Biological Measures in Early Parkinson’s Disease: Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative Cohort. Mov Disord. 2018;33(5):771–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caspell-Garcia C, Simuni T, Tosun-Turgut D, Wu IW, Zhang Y, Nalls M, et al. Multiple modality biomarker prediction of cognitive impairment in prospectively followed de novo Parkinson disease. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0175674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siderowf A, Xie SX, Hurtig H, Weintraub D, Duda J, Chen-Plotkin A, et al. CSF amyloid1-42 predicts cognitive decline in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;75(12):1055–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alves G, Lange J, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Andreasson U, Forland MG, et al. CSF Abeta42 predicts early-onset dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2014;82(20):1784–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guerrero R, Ross OA, Kun-Rodrigues C, Hernandez DG, Orme T, Eicher JD, et al. Investigating the genetic architecture of dementia with Lewy bodies: a two-stage genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(1):64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robinson JL, Lee EB, Xie SX, Rennert L, Suh E, Bredenberg C, et al. Neurodegenerative disease concomitant proteinopathies are prevalent, age-related and APOE4-associated. Brain. 2018;141(7):2181–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dickson DW, Heckman MG, Murray ME, Soto AI, Walton RL, Diehl NN, et al. APOE epsilon4 is associated with severity of Lewy body pathology independent of Alzheimer pathology. Neurology. 2018;91(12):e1182–e95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braak H, Bohl JR, Muller CM, Rub U, de Vos RA, Del Tredici K. Stanley Fahn Lecture 2005: The staging procedure for the inclusion body pathology associated with sporadic Parkinson’s disease reconsidered. Mov Disord. 2006;21(12):2042–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phie J, Krishna SM, Moxon JV, Omer SM, Kinobe R, Golledge J. Flavonols reduce aortic atherosclerosis lesion area in apolipoprotein E deficient mice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Corbo RM, Scacchi R. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) allele distribution in the world. Is APOE*4 a ‘thrifty’ allele? Ann Hum Genet. 1999;63(Pt 4):301–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bales KR, Dodart JC, DeMattos RB, Holtzman DM, Paul SM. Apolipoprotein E, amyloid, and Alzheimer disease. Mol Interv. 2002;2(6):363–75, 39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gallardo G, Schluter OM, Sudhof TC. A molecular pathway of neurodegeneration linking alpha-synuclein to ApoE and Abeta peptides. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(3):301–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cookson MR, van der Brug M. Cell systems and the toxic mechanism(s) of alpha-synuclein. Exp Neurol. 2008;209(1):5–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ballard C, Ziabreva I, Perry R, Larsen JP, O’Brien J, McKeith I, et al. Differences in neuropathologic characteristics across the Lewy body dementia spectrum. Neurology. 2006;67(11):1931–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dalrymple-Alford JC, MacAskill MR, Nakas CT, Livingston L, Graham C, Crucian GP, et al. The MoCA: Well-suited screen for cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;75(19):1717–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoops S, Nazem S, Siderowf AD, Duda JE, Xie SX, Stern MB, et al. Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;73(21):1738–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rabbitt P, Scott M, Thacker N, Lowe C, Jackson A, Horan M, et al. Losses in gross brain volume and cerebral blood flow account for age-related differences in speed but not in fluid intelligence. Neuropsychology. 2006;20(5):549–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marioni RE, Campbell A, Scotland G, Hayward C, Porteous DJ, Deary IJ. Differential effects of the APOE e4 allele on different domains of cognitive ability across the life-course. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24(6):919–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clark LR, Berman SE, Norton D, Koscik RL, Jonaitis E, Blennow K, et al. Age-accelerated cognitive decline in asymptomatic adults with CSF beta-amyloid. Neurology. 2018;90(15):e1306–e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure: (A) Letter-Number Sequencing (B) Semantic verbal Fluency Test (Animals, Vegetables, and Fruits named), and (C) Judgement of Line Orientation over time.

CSF Aβ = Cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid Beta; APOE = Apolipoprotein E; APOE ε4+ = presence of at least one APOE ε4 allele; APOE ε4− = absence of APOE ε4 allele LNS = Letter-Number Sequencing; SFT = Semantic Fluency Test; JLO = Judgement of Line Orientation; CSF Aβ = Cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid Beta; APOE = Apolipoprotein E; APOE ε4+ = presence of at least one APOE ε4 allele; APOE ε4− = absence of APOE ε4 allele