Abstract

Background:

Little is known about those vaccinated against influenza after pharmacists were added to the Ontario Universal Influenza Immunization Program, in 2012. Our aim was to identify characteristics of patients vaccinated against influenza and predictors of vaccination at a physician’s office versus a community pharmacy.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study of Ontario residents who had a record of receipt of an influenza vaccine between October and March in the 2013/14 and 2015/16 influenza seasons in Ontario using health administrative databases. We used Poisson regression models to estimate associations between baseline characteristics and the receipt of influenza vaccination in a community pharmacy. All analyses were stratified by age group (≤ 65 yr or ≥ 66 yr).

Results:

Overall, we found a 7.9% decrease in vaccinations administered in 2015/16 (2 454 178) compared to 2013/14 (2 677 278). The number of patients vaccinated in community pharmacies increased between the 2 periods (757 729 [28.3%] in 2013/14 v. 859 794 [35.0%] in 2015/16). Living in nonurban areas or higher-income neighbourhoods, not identifying as an immigrant, not having a diagnosis of diabetes or hypertension, and receiving a pharmacist service on the same day as the vaccination were predictors of being vaccinated in a pharmacy, regardless of age group. Among patients aged 66 or more, those who had a hospital admission in the previous year were more likely to be vaccinated in a pharmacy than in a physician’s office (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR] 1.08, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06–1.09), whereas those with higher annual medication costs were more likely to be vaccinated in a physician’s office. The location of the previous season’s vaccination predicted the current season’s place of vaccination (age ≥ 66 yr: physician’s office: adjusted IRR 0.56 [95% CI 0.56–0.57], pharmacy: adjusted IRR 2.37 [95% CI 2.35–2.39]; age ≤ 65 yr: physician’s office: adjusted IRR 0.57 [95% CI 0.57–0.57], pharmacy: adjusted IRR 2.19 [95% CI 2.18–2.20]).

Interpretation:

For the 2013/14 and 2015/16 influenza seasons, the influenza vaccine was administered more frequently in physician offices than in community pharmacies, but the proportion of patients vaccinated in community pharmacies increased between the 2 periods. Physicians and pharmacists can encourage patients to take advantage of the availability of influenza vaccines across various settings.

Vaccination is the most effective mechanism to prevent influenza and the resultant morbidity, mortality, work absenteeism and lost productivity.1–7 In 2000, Ontario introduced the Universal Influenza Immunization Program to provide influenza vaccine at no charge to all residents of the province aged 6 months or more through physicians’ offices, public health clinics and workplaces. Although this strategy was effective in increasing overall influenza vaccine coverage, levels remained suboptimal.8–10 In an effort to further improve vaccine coverage, the Universal Influenza Immunization Program was expanded in October 2012 to allow injection-certified pharmacists in community pharmacies to administer influenza vaccines to Ontarians aged 5 years or more. Most Ontario residents live within a short distance of a pharmacy (91% within 5 km and 65% within 800 m),11 and 51% visit a pharmacy at least once per month.12 In addition, pharmacists are available during extended evening and weekend hours, no appointments are necessary for many of their services, and they are available to people who do not have a primary care provider. It was expected that the high degree of public access to trained community pharmacists would improve vaccine coverage. Indeed, similar policies have resulted in long-term absolute increases of 2.2%–7.6% in the number of adults aged 25–59 receiving influenza vaccine (no substantial change for those younger or older) in the United States.13–15 In Canada, people living in a province where influenza vaccine administration by pharmacists is allowed are 5% more likely to be vaccinated than those residing in provinces without this option.16

Although data exist on the impact on influenza vaccine coverage of pharmacists’ being permitted to vaccinate, little research has been done to understand the types of patients who use this service, particularly in comparison to those vaccinated in physicians’ offices. The objectives of the current study were to 1) characterize patients who were vaccinated in a community pharmacy or physician’s office in Ontario and 2) identify predictors of receiving the vaccine in a community pharmacy or physician’s office.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, we identified all people who had a record in Ontario’s population-based health administrative data of receipt of an influenza vaccine in community pharmacies or physician offices between October and March in the 2013/14 and 2015/16 influenza seasons (2 and 4 yr after implementation of the policy allowing pharmacists to vaccinate). We avoided the initial year after implementation, when the service was introduced across a limited number of pharmacies. At the time the study was conducted, the most recent health administrative data available were for the 2015/16 influenza season (there is a delay of about 18 mo between end of influenza season and data availability). The health administrative data sets were linked by means of unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. A description of the databases is provided in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/2/E421/suppl/DC1). The ICES is an independent, nonprofit research institute whose legal status under Ontario’s health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyze health care and demographic data, without consent, for health care system evaluation and improvement. If more than 1 vaccination was registered for the same patient within an influenza season, the earliest vaccination in the season was used as the patient’s index date.

Influenza vaccination data sources

The Ontario Health Insurance Plan billing claims database captures influenza vaccines administered in physician offices by means of service provision codes and is validated.17 Community pharmacies bill for an influenza vaccination administration fee by processing a claim for that product to the government payer using its Drug Identification Number. This information is contained in the Ontario Drug Benefit database. The claim is associated with the pharmacy rather than a specific pharmacist; hence in this study we refer to vaccine administration in a community pharmacy (understanding that these were vaccines administered by community pharmacists). Appendix 2 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/2/E421/suppl/DC1) provides the Ontario Health Insurance Plan service codes and Ontario Drug Benefit Drug Identification Numbers used for data extraction.

Patient characteristics at time of vaccination

We determined individual baseline characteristics relative to the index date (i.e., vaccination date). We used the Ontario Registered Persons Database to determine age, sex, Rurality Index of Ontario (RIO) score and neighbourhood income quintile of residence. The RIO score is a continuous measure of remoteness specific to Ontario that accounts for community size and travel time to basic and advanced medical centres.18 Patients were grouped into urban (RIO score 0–9), nonmajor urban (RIO score 10–39) and rural (RIO score ≥ 40) residence. We obtained neighbourhood income quintile, which has been shown to be a reasonable proxy for socioeconomic status,19 by linking patient postal codes to Canadian census data. We used the Ontario portion of the Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada database to determine the landing date for immigrants to Ontario since 1985. Patients were classified as landing less than 5 years earlier, 5–9 years earlier, or 10 years or more earlier, or being a long-term resident.

We applied validated algorithms to the health care databases to determine selected diagnoses as of the time of vaccination that are associated with higher influenza morbidity and mortality: diabetes,20 hypertension,21 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,22 asthma,23 congestive heart failure24 and acute myocardial infarction.25 We determined the incidence of cancer, except nonmelanoma skin cancers, using the Ontario Cancer Registry.26

We identified patients requiring a hospital admission, emergency department visit or home care visit in the previous year using the Discharge Abstract Database, National Ambulatory Care Reporting System and Home Care Database, respectively. Information regarding the number of physician office visits in the previous year and whether a patient received a periodic health examination was obtained from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database. For patients aged 66 years or more, we used the Ontario Drug Benefit database to capture the number of unique prescription medications prescribed in the previous year, categorize their total cost (< $500, $500–$999, $1000–$1999, $2000–$2999, $3000– $3999, ≥ $4000) and flag whether the recipient had low-income status. Because drug coverage in Ontario is universal only for adults aged 65 years or more, we measured prescription medications only for those aged 66 or more so that 1 year of data were available to calculate drug costs. However, since residents of all ages qualify for pharmacist services (MedsCheck Annual, MedsCheck Diabetes, MedsCheck at Home, Pharmaceutical Opinion Program and Pharmacy Smoking Cessation Program),27 we used the Ontario Drug Benefit database to assess receipt of these services in the entire study population in the year before (including up to the day of) vaccination.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were stratified by age group (≤ 65 yr or ≥ 66 yr). We summarized descriptive characteristics of patients as means or proportions. We used Poisson regression models, modified to analyze binary outcome data by incorporating a robust sandwich estimator to account for the misspecified error term,28 to estimate the adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) between all of the measured baseline characteristics and receipt of influenza vaccination in a pharmacy. Because the outcome of receiving influenza vaccination from a pharmacist was relatively common, using standard logistic regression models to estimate odds ratios would have overestimated the measure of effect for each predictor.29 We performed analyses using SAS Enterprise Guide version 9.3 (SAS Institute) and Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp).

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Board of the University of Waterloo.

Results

Characteristics by age group and influenza season

The total number of people recorded in the administrative data as vaccinated decreased by 7.9% between the 2013/14 (n = 2 677 287) and 2015/16 (n = 2 465 178) influenza seasons, with a 14.2% decrease (1 691 125 to 1 450 594) among those aged 65 years or less and a 2.9% increase (986 162 to 1 014 584) among those aged 66 or more. The characteristics of patients vaccinated in the 2 seasons by age group are summarized in Appendix 3 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/2/E421/suppl/DC1). Few differences were seen between influenza seasons. A higher proportion of patients aged 66 or more than of those aged 65 or less lived in rural areas, were not recent immigrants, had several chronic diseases, had been vaccinated in the previous year in physicians’ offices, had used health care services (including remunerated pharmacist services) in the previous year and were vaccinated in October.

Characteristics by age group, influenza season and vaccine provider

Table 1 presents information about those vaccinated by age group, influenza season and provider location. The proportion of patients vaccinated in physicians’ offices was higher in both age groups and both influenza seasons but decreased between the 2013/14 and 2015/16 seasons, from 67.1% (n = 1 135 212) to 60.9% (n = 883 055) among those aged 65 or less, and from 79.5% (n = 784 346) to 71.2% (n = 722 329) among older patients. In the 2013/14 influenza season, 537 155 (47.3%) of those aged 65 or less vaccinated in a physician’s office had been vaccinated in a physician’s office the previous year, compared to 593 096 (75.6%) of those aged 66 or more; little change was seen in 2015/16. In contrast, in both age groups, there was a marked increase between the 2013/14 and 2015/16 influenza seasons in the number vaccinated in a community pharmacy among those who had received the vaccine in a community pharmacy the previous year: 93 868 (16.9%) to 281 121 (49.5%) among those aged 65 or less, and 33 207 (16.4%) to 156 379 (53.5%) among those aged 66 or more.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of Ontario residents vaccinated in the 2013/14 and 2015/16 influenza seasons, by age group and location of vaccination provider

| Characteristic | 2013/14 influenza season; location of vaccination, no. (%) of patients* | 2015/16 influenza season, location of vaccination no. (%) of patients* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Age ≤ 65 yr | Age ≥ 66 yr | Age ≤ 65 yr | Age ≤ 66 yr | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Pharmacy n = 555 913 |

Physician’s office n = 1 135 212 |

Pharmacy n = 201 816 |

Physician’s office n = 784 346 |

Pharmacy n = 567 539 |

Physician’s office n = 883 055 |

Pharmacy n = 292 255 |

Physician’s office n = 722 329 |

|

| Demographic | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age at vaccination, yr, mean ± SD | 42.35 ± 17.79 | 40.02 ± 20.46 | 74.58 ± 6.95 | 75.99 ± 7.20 | 43.35 ± 17.75 | 40.73 ± 20.41 | 74.89 ± 7.03 | 76.09 ± 7.27 |

|

| ||||||||

| Female sex | 303 116 (54.5) | 627 361 (55.3) | 110 136 (54.6) | 428 674 (54.7) | 311 438 (54.9) | 491 171 (55.6) | 159 545 (54.6) | 392 979 (54.4) |

|

| ||||||||

| Rurality Index of Ontario score | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Urban | 400 929 (72.1) | 900 265 (79.3) | 128 967 (63.9) | 554 548 (70.7) | 407 899 (71.9) | 704 958 (79.8) | 182 367 (62.4) | 516 802 (71.5) |

|

| ||||||||

| Nonmajor urban | 128 929 (23.2) | 199 741 (17.6) | 58 752 (29.1) | 190 992 (24.4) | 132 262 (23.3) | 151 809 (17.2) | 88 473 (30.3) | 171 354 (23.7) |

|

| ||||||||

| Rural | 26 055 (4.7) | 35 206 (3.1) | 14 097 (7.0) | 38 806 (4.9) | 27 378 (4.8) | 26 288 (3.0) | 21 415 (7.3) | 34 173 (4.7) |

|

| ||||||||

| Neighbourhood income quintile | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 81 645 (14.7) | 215 212 (19.0) | 31 307 (15.5) | 135 463 (17.3) | 84 275 (14.8) | 163 833 (18.6) | 44 625 (15.3) | 122 375 (16.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| 2 | 94 213 (16.9) | 221 639 (19.5) | 37 899 (18.8) | 160 329 (20.4) | 96 782 (17.1) | 172 238 (19.5) | 53 953 (18.5) | 146 153 (20.2) |

|

| ||||||||

| 3 | 106 402 (19.1) | 227 810 (20.1) | 38 281 (19.0) | 156 294 (19.9) | 109 083 (19.2) | 177 109 (20.1) | 56 336 (19.3) | 144 092 (19.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| 4 | 125 795 (22.6) | 239 132 (21.1) | 43 712 (21.7) | 163 581 (20.9) | 130 181 (22.9) | 191 164 (21.6) | 63 825 (21.8) | 154 003 (21.3) |

|

| ||||||||

| 5 (highest) | 147 858 (26.6) | 231 419 (20.4) | 50 617 (25.1) | 168 679 (21.5) | 147 218 (25.9) | 178 711 (20.2) | 73 516 (25.2) | 155 706 (21.6) |

|

| ||||||||

| Low income | NA | NA | 19 746 (9.8) | 124 216 (15.8) | NA | NA | 26 320 (9.0) | 103 719 (14.4) |

|

| ||||||||

| Month of vaccination | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| October | 139 731 (25.1) | 440 771 (38.8) | 85 260 (42.2) | 450 054 (57.4) | 99 753 (17.6) | 245 473 (27.8) | 82 537 (28.2) | 309 345 (42.8) |

|

| ||||||||

| November | 237 952 (42.8) | 418 580 (36.9) | 87 501 (43.4) | 262 335 (33.4) | 343 003 (60.4) | 421 753 (47.8) | 172 606 (59.1) | 324 576 (44.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| December | 59 119 (10.6) | 124 597 (11.0) | 13 857 (6.9) | 45 878 (5.8) | 95 324 (16.8) | 150 302 (17.0) | 29 988 (10.3) | 67 038 (9.3) |

|

| ||||||||

| January | 113 432 (20.4) | 129 580 (11.4) | 14 556 (7.2) | 22 433 (2.9) | 23 256 (4.1) | 47 380 (5.4) | 5913 (2.0) | 16 638 (2.3) |

|

| ||||||||

| February | 4823 (0.9) | 17 492 (1.5) | 569 (0.3) | 2998 (0.4) | 4808 (0.8) | 13 865 (1.6) | 1029 (0.4) | 3732 (0.5) |

|

| ||||||||

| March | 856 (0.2) | 4192 (0.4) | 73 (0.04) | 648 (0.1) | 1395 (0.2) | 4282 (0.5) | 182 (0.1) | 1000 (0.1) |

|

| ||||||||

| Time since immigration, yr | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Nonimmigrant | 494 681 (89.0) | 920 309 (81.1) | 194 136 (96.2) | 716 582 (91.4) | 503 451 (88.7) | 719 352 (81.5) | 279 858 (95.8) | 656 326 (90.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| < 5 | 11 552 (2.1) | 40 211 (3.5) | 813 (0.4) | 5469 (0.7) | 6013 (1.1) | 14 291 (1.6) | 600 (0.2) | 2886 (0.4) |

|

| ||||||||

| 5–9 | 13 002 (2.3) | 44 758 (3.9) | 1009 (0.5) | 7729 (1.0) | 13 808 (2.4) | 33 501 (3.8) | 1609 (0.6) | 7656 (1.1) |

|

| ||||||||

| ≥ 10 | 36 678 (6.6) | 129 934 (11.4) | 5858 (2.9) | 54 566 (7.0) | 44 267 (7.8) | 115 911 (13.1) | 10 188 (3.5) | 55 461 (7.7) |

|

| ||||||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Diabetes | 54 584 (9.8) | 168 581 (14.9) | 53 936 (26.7) | 264 997 (33.8) | 62 665 (11.0) | 144 678 (16.4) | 81 964 (28.0) | 256 396 (35.5) |

|

| ||||||||

| Hypertension | 121 978 (21.9) | 308 227 (27.2) | 140 459 (69.6) | 611 099 (77.9) | 130 272 (23.0) | 245 319 (27.8) | 204 878 (70.1) | 562 473 (77.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 9398 (1.7) | 26 884 (2.4) | 17 440 (8.6) | 80 492 (10.3) | 10 869 (1.9) | 22 807 (2.6) | 25 416 (8.7) | 74 029 (10.2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Asthma | 95 131 (17.1) | 205 529 (18.1) | 25 396 (12.6) | 115 787 (14.8) | 99 150 (17.5) | 162 238 (18.4) | 38 815 (13.3) | 110 502 (15.3) |

|

| ||||||||

| Congestive heart failure | 4817 (0.9) | 14 809 (1.3) | 15 172 (7.5) | 81 333 (10.4) | 5630 (1.0) | 12 601 (1.4) | 22 626 (7.7) | 75 666 (10.5) |

|

| ||||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 5906 (1.1) | 15 179 (1.3) | 10 648 (5.3) | 45 921 (5.9) | 6190 (1.1) | 12 374 (1.4) | 15 243 (5.2) | 42 086 (5.8) |

|

| ||||||||

| Cancer† | 18 570 (3.3) | 40 066 (3.5) | 30 555 (15.1) | 121 804 (15.5) | 23 249 (4.1) | 37 210 (4.2) | 49 457 (16.9) | 125 255 (17.3) |

|

| ||||||||

| Use of health care services in previous year | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Influenza vaccination in physician’s office | 132 308 (23.8) | 537 155 (47.3) | 92 143 (45.7) | 593 096 (75.6) | 91 801 (16.2) | 406 390 (46.0) | 87 363 (29.9) | 515 454 (71.4) |

|

| ||||||||

| Influenza vaccination in community pharmacy | 93 868 (16.9) | 27 364 (2.4) | 33 207 (16.4) | 15 944 (2.0) | 281 121 (49.5) | 82 324 (9.3) | 156 379 (53.5) | 74 034 (10.2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Hospital admission | 23 828 (4.3) | 80 604 (7.1) | 19 907 (9.9) | 93 660 (11.9) | 24 557 (4.3) | 66 061 (7.5) | 28 519 (9.8) | 86 168 (11.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| Emergency department visit | 121 020 (21.8) | 268 251 (23.6) | 55 602 (27.6) | 227 776 (29.0) | 124 111 (21.9) | 213 063 (24.1) | 81 315 (27.8) | 214 099 (29.6) |

|

| ||||||||

| Home care | 14 442 (2.6) | 37 564 (3.3) | 23 233 (11.5) | 113 629 (14.5) | 15 529 (2.7) | 30 896 (3.5) | 33 233 (11.4) | 104 690 (14.5) |

|

| ||||||||

| No. of physician office visits, mean ± SD | 8.43 ± 12.25 | 11.25 ± 14.15 | 14.30 ± 15.83 | 18.02 ± 18.59 | 8.83 ± 12.86 | 11.72 ± 14.91 | 14.17 ± 15.67 | 17.92 ± 18.70 |

|

| ||||||||

| Periodic health examination | 36 291 (6.5) | 79 012 (7.0) | 16 748 (8.3) | 66 430 (8.5) | 30 867 (5.4) | 45 541 (5.2) | 18 865 (6.5) | 43 415 (6.0) |

|

| ||||||||

| Use of pharmacy services in previous year | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| No. of unique prescription medications, mean ± SD | NA | NA | 9.59 ± 6.31 | 10.27 ± 6.94 | NA | NA | 9.65 ± 6.25 | 10.18 ± 6.90 |

|

| ||||||||

| Total cost of prescription medications, $ | NA | NA | 1373.28 ± 3764.67 | 1596.94 ± 3343.26 | NA | NA | 1446.58 ± 4113.70 | 1655.59 ± 3731.92 |

|

| ||||||||

| < 500 | NA | NA | 83 738 (41.5) | 260 435 (33.2) | NA | NA | 125 613 (43.0) | 253 066 (35.0) |

|

| ||||||||

| 500–999 | NA | NA | 42 057 (20.8) | 168 536 (21.5) | NA | NA | 60 133 (20.6) | 152 874 (21.2) |

|

| ||||||||

| 1000–1999 | NA | NA | 39 853 (19.7) | 177 024 (22.6) | NA | NA | 53 761 (18.4) | 153 428 (21.2) |

|

| ||||||||

| 2000–2999 | NA | NA | 17 184 (8.5) | 82 927 (10.6) | NA | N/A | 24 409 (8.4) | 74 183 (10.3) |

|

| ||||||||

| 3000–3999 | NA | NA | 7943 (3.9) | 39 555 (5.0) | NA | N/A | 10 827 (3.7) | 34 964 (4.8) |

|

| ||||||||

| ≥ 4000 | NA | NA | 11 041 (5.5) | 55 869 (7.1) | NA | NA | 17 512 (6.0) | 53 814 (7.5) |

|

| ||||||||

| Pharmacist service | 59 275 (10.7) | 122 507 (10.8) | 75 413 (37.4) | 285 434 (36.4) | 63 983 (11.3) | 102 774 (11.6) | 103 553 (35.4) | 260 805 (36.1) |

|

| ||||||||

| Pharmacist service on day of vaccination | 4238 (0.8) | 3387 (0.3) | 4848 (2.4) | 6835 (0.9) | 4760 (0.8) | 2913 (0.3) | 7117 (2.4) | 6074 (0.8) |

Note: NA = not applicable, SD = standard deviation.

Except where noted otherwise.

Except nonmelanoma skin cancers.

Predictors of vaccination location

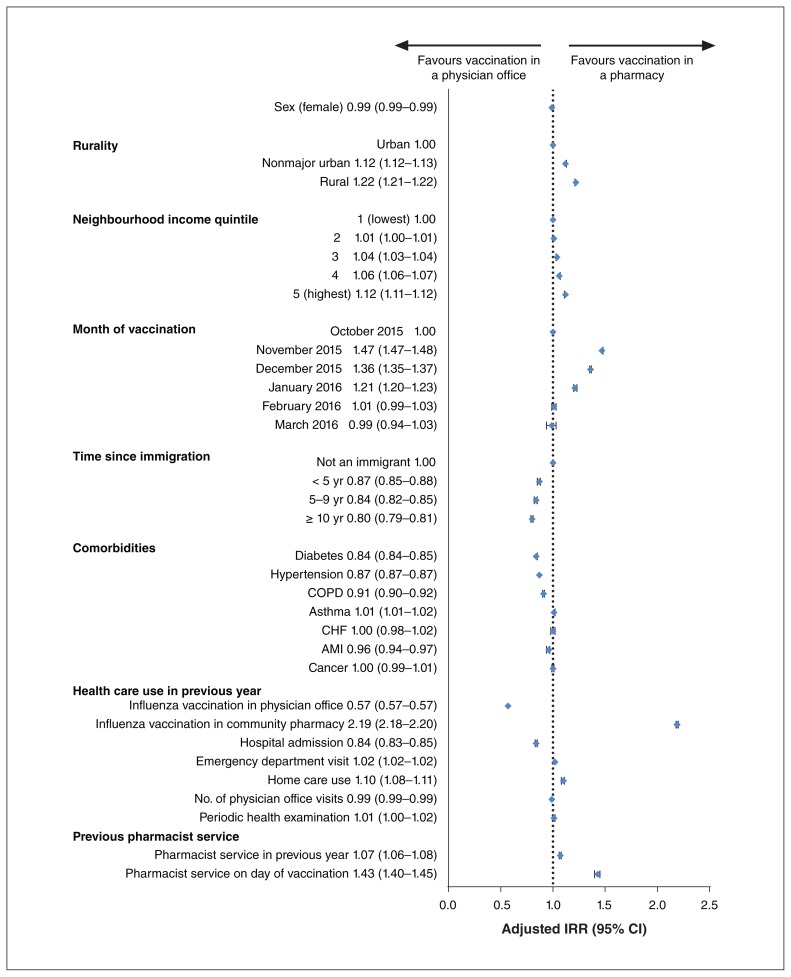

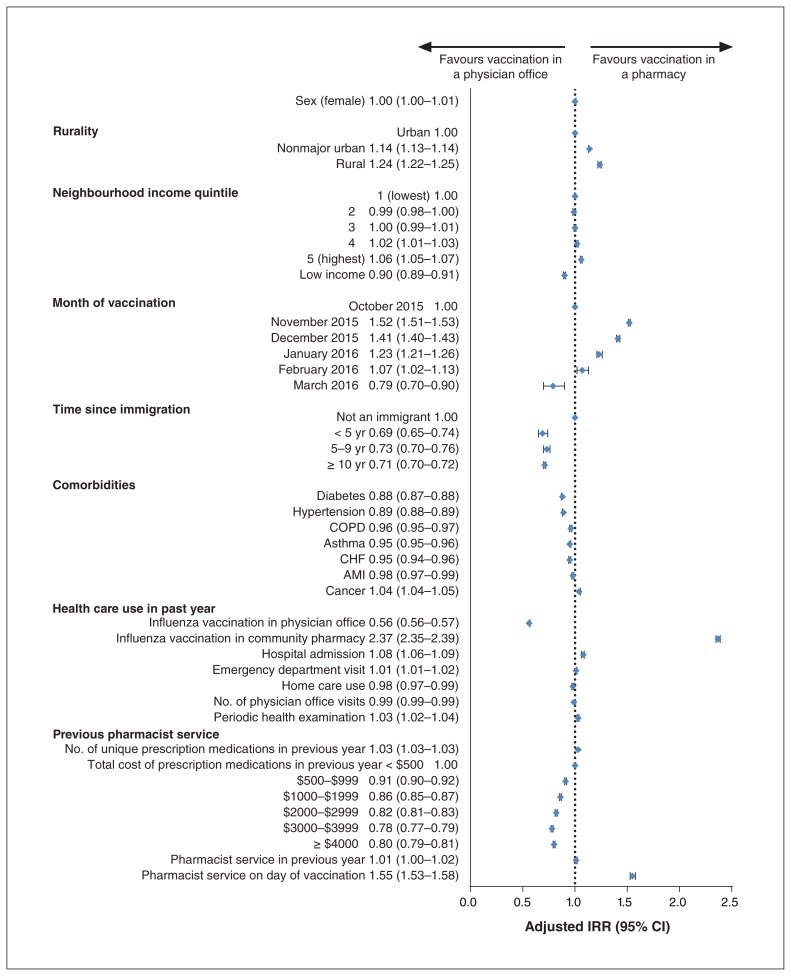

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the IRRs for being vaccinated in physicians’ offices compared to community pharmacies for patients aged 65 or less and 66 or more, respectively, for the 2015/16 influenza season. Living in smaller communities, living in the highest income quintile neighbourhoods and receiving a pharmacist service on the same day as the vaccination were all predictive of being vaccinated in a pharmacy, whereas identifying as an immigrant, prior vaccination in a physician’s office and the presence of certain chronic health conditions (diabetes and hypertension) were associated with vaccination in a physician’s office, regardless of age group. The location of the previous year’s vaccination (whether physician’s office or pharmacy) was a strong predictor of the vaccine provider for the current influenza season. Among patients aged 65 or less, hospital admission in the previous year predicted vaccination in a physician’s office, and home care use or provision of a pharmaceutical service in the previous year predicted vaccination in a pharmacy. Among patients aged 66 or more, hospital admission in the previous year was predictive of vaccination in a pharmacy, whereas low-income status and higher annual medication costs were predictive of vaccination in a physician’s office. Being vaccinated in November, December or January was predictive of vaccination in a pharmacy for all age groups, whereas, for those aged 66 or more, being vaccinated in March predicted vaccination in a physician’s office.

Figure 1:

Adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for being vaccinated in a physician’s office versus a community pharmacy for patients aged 65 years or less. Note: AMI = acute myocardial infarction, CHF = congestive heart failure, CI = confidence interval, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Figure 2:

Adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for being vaccinated in a physician’s office versus a community pharmacy for patients aged 66 years or more. Note: AMI = acute myocardial infarction, CHF = congestive heart failure, CI = confidence interval, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Predictors of vaccination location for the 2013/14 influenza season were the same as for the 2015/16 season except that people aged 65 or less were more likely to be vaccinated in physician offices than in pharmacies in February and March, versus no association in 2015/16.

Interpretation

For the 2013/14 and 2015/16 influenza seasons, Ontarians were more likely to have received the influenza vaccine in a physician’s office than in a community pharmacy, but there was an increase in the proportion of vaccines administered in a pharmacy between the 2 seasons. This likely reflects an increased awareness of the availability of this pharmacist service through public health, word-of-mouth and pharmacy-specific advertising.30,31

Over the past 20 years, pharmacists have been increasingly involved as partners with other health care professionals and public health departments in vaccination campaigns and as vaccinators themselves.32–35 Pharmacists can administer 1, several or all vaccines across all US states and in 9 of the 10 Canadian provinces, with influenza vaccination permitted in all jurisdictions where pharmacists can vaccinate.36,37 In Ontario, pharmacists have been able to administer influenza vaccine since 2012, and this program was expanded in 2016 to include other, travel-related vaccines.

Patient response to pharmacists as vaccinators has been positive.30,31 For example, Papastergiou and colleagues30 found that 92% of patients who had been vaccinated by a pharmacist were “very satisfied” with the service, with 28% of respondents overall and 21% of patients at high risk for influenza complications indicating that they would not have been vaccinated at all if the service had not been available at the pharmacy.

In the current study, demographic predictors of influenza vaccination in a physician’s office included living in an urban area or lower-income neighbourhood, identifying as an immigrant, having a chronic disease such as diabetes or hypertension, and being an older adult with a low income or a higher drug cost burden.

Loyalty and familiarity appeared to play an important role in determining the location of influenza vaccination, as shown by the strong association between the current year’s and previous year’s vaccination location. A patient survey following vaccination by a pharmacist showed that 92% of respondents would receive their next influenza vaccine at a pharmacy.30 Interestingly, physician office visits and periodic physician health examinations within the prior year were not predictive of vaccination in a physician’s office, and receipt of pharmacist services in the previous year was a weak predictor of pharmacist administration of influenza vaccine. Although infrequent (less than 2% of patients), receiving another pharmacist service on the day of vaccination was highly associated with influenza vaccination at a pharmacy. This may occur as a result of pharmacists’ recommending the influenza vaccine during an activity such as a medication review or using the influenza vaccine opportunity to inquire about medication use, leading to provision of another pharmacist service.

Limitations

Ontario residents can get vaccinated in locations other than physician offices and pharmacies, such as public health and long-term care facilities and workplaces. Vaccination data from these locations are not collected at the individual patient level (not linkable to ICES demographic or health data) and, therefore, are not included in this study. Errors in the billing data are also a possibility. The covariates related to prescription drug claims are limited to people aged 65 years or more, and, thus, predictive status is unknown for those aged less than 65 years. In determining the difference between influenza seasons, we did not use a multivariable model as the samples were not independent, with many of the same people in both influenza seasons. In addition, the large sample meant that small differences between seasons were statistically significant; instead, we used our clinical judgment to determine where differences occurred between influenza seasons. Finally, in Ontario, pharmacists cannot vaccinate children less than 5 years of age, so comparative data for this age group were not available.

Conclusion

For the 2013/14 and 2015/16 influenza seasons, the influenza vaccine was administered more frequently in physician offices than in community pharmacies, but the proportion of patients vaccinated in community pharmacies increased between the 2 periods. Living in smaller communities, living in the highest income quintile neighbourhoods and receiving a pharmacist service on the same day as the vaccination were all predictive of being vaccinated in a pharmacy, whereas identifying as an immigrant and the presence of certain chronic health conditions (diabetes and hypertension) were associated with vaccination in a physician’s office, regardless of age group. The location of the previous year’s vaccination (whether physician’s office or pharmacy) was a strong predictor of the vaccine provider for the current influenza season. To further increase influenza vaccine coverage, health care providers can use this information to target patients they are more likely to vaccinate and to identify mechanisms to promote vaccination to those they are less likely to vaccinate. This information also represents an opportunity for physicians and pharmacists to encourage patients to take advantage of the availability of influenza vaccine across various settings, to best align with their preferences and encourage uptake.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dana Church and Emily Milne for their facilitation of research meetings, data management and conducting literature reviews, Hannah Chung for her assistance with data management and figure development, and Richard Violette for editing a previous version of the manuscript and assistance with graphics.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Sherilyn Houle and Nancy Waite have received educational grants from Merck and Sanofi, and Sherilyn Houle received support for a graduate student trainee from Valneva Canada. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Nancy Waite, Jeffrey Kwong, Suzanne Cadarette, Michael Campitelli and Giulia Consiglio conceived and designed the study, and contributed to data interpretation and drafting the manuscript. Michael Campitelli completed the data extraction and analysis. Sherilyn Houle contributed to data interpretation and drafting the manuscript. All of the authors approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, the Ontario Pharmacy Evidence Network (OPEN) and the Government of Ontario.

Disclaimer: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Information.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/2/E421/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Advisory Committee Statement. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018. National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI): Canadian immunization guide chapter on influenza and statement on seasonal influenza vaccine for 2018–2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schanzer DL, Langley JM, Tam TW. Role of influenza and other respiratory viruses in admissions of adults to Canadian hospitals. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2008;2:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2008.00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schanzer DL, Tam TW, Langley JM, et al. Influenza-attributable deaths, Canada 1990–1999. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:1109–16. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807007923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li S, Leader S. Economic burden and absenteeism from influenza-like illness in healthy households with children (5–17 years) in the US. Respir Med. 2007;101:1244–50. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molinari NA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Messonnier ML, et al. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine. 2007;25:5086–96. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schanzer DL, Zheng H, Gilmore J. Statistical estimates of absenteeism attributable to seasonal and pandemic influenza from the Canadian Labour Force Survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwong JC, Stukel TA, Lim J, et al. The effect of universal influenza immunization on mortality and health care use. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwong JC, Rosella LC, Johansen H. Trends in influenza vaccination in Canada, 1996/1997 to 2005. Health Rep. 2007;18:9–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchan SA, Kwong JC. Trends in influenza vaccine coverage and vaccine hesitancy in Canada, 2006/07 to 2013/14: results from cross-sectional survey data. CMAJ Open. 2016;4:E455–62. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Law MR, Dijkstra A, Douillard JA, et al. Geographic accessibility of community pharmacies in Ontario. Healthc Policy. 2011;6:36–46. doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2011.22097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Report no. 2. Ottawa: Abacus Data; 2015. Pharmacists in Canada: a national survey of Canadians on their perceptions and attitudes towards pharmacists in Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drozd EM, Miller L, Johnsrud M. Impact of pharmacist immunization authority on seasonal influenza immunization rates across states. Clin Ther. 2017;39:1563–80.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isenor JE, Killen JL, Billard BA, et al. Impact of pharmacists as immunizers on influenza vaccination coverage in the community-setting in Nova Scotia, Canada: 2013–2015. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2016;9:32. doi: 10.1186/s40545-016-0084-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baroy J, Chung D, Frisch R, et al. The impact of pharmacist immunization programs on adult immunization rates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2016;56:418–26. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchan SA, Rosella LC, Finkelstein F, et al. Public Health Agency of Canada/Canadian Institutes of Health Research Influenza Research Network (PCIRN) Program Delivery and Evaluation Group. Impact of pharmacist administration of influenza vaccines on uptake in Canada. CMAJ. 2017;189:E146–52. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz KL, Jembere N, Campitelli MA, et al. Using physician billing claims from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan to determine individual influenza vaccination status: an updated validation study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4:E463–70. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kralj B. Measuring rurality — RIO2008_BASIC: methodology and results. Toronto: Economics Department, Ontario Medical Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finkelstein MM. Ecologic proxies for household income: How well do they work for the analysis of health and health care utilization? Can J Public Health. 2004;95:90–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03405773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, et al. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:512–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tu K, Campbell NR, Chen ZL, et al. Accuracy of administrative databases in identifying patients with hypertension. Open Med. 2007;1:e18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, et al. Identifying individuals with physician diagnosed COPD in health administrative databases. COPD. 2009;6:388–94. doi: 10.1080/15412550903140865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, et al. Identifying patients with physician-diagnosed asthma in health administrative databases. Can Respir J. 2009;16:183–8. doi: 10.1155/2009/963098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schultz SE, Rothwell DM, Chen Z, et al. Identifying cases of congestive heart failure from administrative data: a validation study using primary care patient records. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2013;33:160–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tu JV, Naylor CD, Austin P. Temporal changes in the outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in Ontario, 1992–1996. CMAJ. 1999;161:1257–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall S, Schulze K, Groome P, et al. Using cancer registry data for survival studies: the example of the Ontario Cancer Registry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health care professionals: MedsCheck. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2017. [accessed 2017 Apr 3]. Available: http://health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/medscheck/medscheck_original.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, et al. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:940–3. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papastergiou J, Folkins C, Li W, et al. Community pharmacist-administered influenza immunization improves patient access to vaccination. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2014;147:359–65. doi: 10.1177/1715163514552557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poulose S, Cheriyan E, Cheriyan R, et al. Pharmacist-administered influenza vaccine in a community pharmacy: a patient experience survey. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2015;148:64–7. doi: 10.1177/1715163515569344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Policy statement no. 200614. Washington: American Public Health Association; 2006. [accessed 2017 Apr 3]. The role of the pharmacist in public health. Available: www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/07/13/05/the-role-of-the-pharmacist-in-public-health. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agomo CO. The role of community pharmacists in public health: a scoping review of the literature. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2012;3:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith M. Pharmacists’ role in public and population health. Ann Public Health Res. 2014;1:1006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eades CE, Ferguson JS, O’Carroll RE. Public health in community pharmacy: a systematic review of pharmacist and consumer views. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:582. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Immunization authority. Washington: American Pharmacists Association; 2018. [accessed 2018 Feb 6]. Available: www.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/IZ_Authority_012018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pharmacists’ scope of practice in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2016. [accessed 2017 Apr 3]. Available: www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/pharmacy-in-canada/Scope%20of%20Practice%20in%20Canada_JAN2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.