QT prolongation is associated with increased mortality in different types of patients [1, 2]. QT prolongation is common in critically ill patients [3], and the association between heart rate corrected QT (QTc) and outcome in critically ill patients has raised broad interests most recently [4]. However, the prevalence of new-onset QT prolongation and its significance in these patients was not well studied yet.

Here, we prospectively recruited 505 consecutive ICU patients without known previous QT prolongation to evaluate the risk factors for new-onset QT prolongation and the prognostic value of QTc calculated by different methods. The baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics of subjects were shown in Table 1. The mean Bazett QT interval was 413.6 ± 33.8 ms. New-onset QT prolongation occurred in 99 patients (19.6%). This occurrence is about 200-fold higher than that in the general population [5]. Intriguingly, the occurrence of nonthyroidal illness syndrome (NTIS) is significantly higher in patients with QT prolongation than those without (Table 1), indicating that NTIS might be a risk factor of QT prolongation. Indeed, multivariate linear regression showed that QTc was independently associated with NTIS, heart rate, level of serum potassium, gender, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of subjects

| All | Normal QT (N = 406) | QT prolongation (N = 99) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.7 ± 18.2 | 62.8 ± 18.5 | 67.4 ± 16.6 | 0.20 |

| Male (%) | 305 (60.4) | 237 (58.4) | 68 (68.7) | 0.06 |

| Heart rate (BPM) | 85.2 ± 20.4 | 83.7 ± 20.8 | 91.3 ± 17.5 | 0.01 |

| Positive cTNT (%) | 52.5 | 46.5 | 76.8 | < 0.001 |

| LogNT-proBNP | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 0.91 |

| Na+ (mmol/L) | 140.2 ± 5.7 | 140.0 ± 5.5 | 141.0 ± 6.5 | 0.15 |

| K+ (mmol/L) | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 0.10 |

| Cl- (mmol/L) | 104.7 ± 6.4 | 104.6 ± 6.0 | 105.5 ± 7.8 | 0.04 |

| Ca2+ (mmol/L) | 2.08 ± 0.21 | 2.10 ± 0.19 | 2.02 ± 0.25 | 0.001 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 7.53 ± 3.28 | 7.36 ± 3.02 | 8.26 ± 4.15 | 0.02 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 86.7 ± 44.1 | 91.6 ± 42.9 | 66.3 ± 43.5 | 0.49 |

| CKD grade# | 1.95 ± 1.13 | 1.80 ± 1.01 | 2.56 ± 1.35 | < 0.001 |

| APACHE- II (points) | 15.0 ± 8.4 | 14.2 ± 8.0 | 18.7 ± 9.2 | 0.006 |

| TT3 (nmol/L) | 0.92 ± 0.45 | 0.96 ± 0.48 | 0.73 ± 0.25 | 0.004 |

| TT4 (nmol/L) | 86.4 ± 30.1 | 88.7 ± 30.9 | 77.4 ± 24.8 | 0.19 |

| FT3 (pmol/L) | 3.44 ± 1.10 | 3.52 ± 1.18 | 3.15 ± 0.59 | 0.17 |

| FT4 (pmol/L) | 15.5 ± 4.8 | 15.5 ± 5.1 | 15.4 ± 3.6 | 0.67 |

| TSH (IU/mL) | 1.34 ± 1.35 | 1.34 ± 1.28 | 1.32 ± 1.61 | 0.06 |

| #NTIS (%) | 59.3 | 55.0 | 76.3 | < 0.001 |

BPM beats per minute, FBG fasting blood glucose, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, CKD chronic kidney disease, APACHE II score Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score. TT3 total triiodothyronine, TT4 total thyroxine, FT3 free triiodothyronine, FT4 free thyroxine, TSH thyroid-stimulating-hormone, rT3 reverse triiodothyronine, NTIS nonthyroidal illness syndrome

#NTIS: Euthyroid patients with fT3 decreased below the normal range (< 3.5 pmol/L) during critical illness

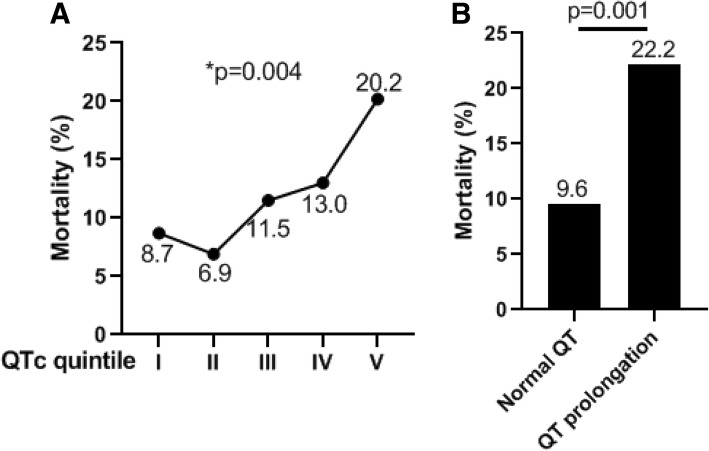

There was a significantly graded increase in mortality rate across increasing QTc quintile (p = 0.004) (Fig. 1a). The overall mortality rate in patients with a new-onset QTc prolongation is more than two times higher than those patients without (22.2% vs 9.6, OR = 2.69, p = 0.001) (Fig. 1b). Multivariate logistic regression showed that QT prolongation is still independently associated with ICU mortality even after adjusted for age and gender (p = 0.001, 95% C.I., 1.51–4.79). However, QT prolongation is no longer a predictor of ICU mortality if APACHE-II score was further adjusted (p = 0.329), likely due to that QTc itself is strongly associated with APACHE-II score (r = − 0.235, p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

a ICU mortality rates among patients with different QTc quintile. *Linear-by-Linear Association by chi-square test. b Overall ICU mortality rates among patients with or without QT prolongation

As Bazett’s formula can over-correct QT at high heart rates and under-correct it at low heart rates, we then evaluated the prognostic value of QTc calculated using additional formulas including Fridericia’s, Framingham’s, and Hodges’s. We found that patients in quintile 5 have significantly higher mortality than patients in the combination of quintiles 1–4 regardless of which formula was used (all p < 0.05).

In summary, QT prolongation determined by baseline ECG can serve as a novel indicator of the severity of illness in critically ill patients. NTIS is a new risk factor of QT prolongation in critically ill patients.

Acknowledgements

None

Abbreviations

- APACHE-II score

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score

- eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- NTIS

Nonthyroidal illness syndrome

- QTc

Heart rate-corrected QT

Authors’ contributions

FW conceived and designed the study. YD, RJ, LR, and WP contributed to data acquisition and analysis. QL interpreted the data and provided insightful input to this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the “Gaoyuan” project from Pudong Health and Family Planning Commission (PWYgy2018-06).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Shanghai Jiaotong University Xinhua Hospital Ethics Committee (XHEC2011-002).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yonghe Ding and Ryounghoon Jeon contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yonghe Ding, Email: dingyonghe@qdu.edu.cn.

Ryounghoon Jeon, Email: jeon.ryounghoon@mayo.edu.

Wenzhi Pan, Email: pansm2010@sina.cn.

Feilong Wang, Email: dr.feilongwang@gmail.com.

Qiang Li, Email: liqressh@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.O'Neal WT, Singleton MJ, Roberts JD, Tereshchenko LG, Sotoodehnia N, Chen LY, Marcus GM, Soliman EZ. Association between QT-interval components and sudden cardiac death: the ARIC study (atherosclerosis risk in communities). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10:e005485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Zhang Y, Post WS, Dalal D, Blasco-Colmenares E, Tomaselli GF, Guallar E. QT-interval duration and mortality rate: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1727–1733. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukui S, Katoh H, Tsuzuki N, Ishihara S, Otani N, Ooigawa H, Toyooka T, Ohnuki A, Miyazawa T, Nawashiro H, Shima K. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for QT prolongation following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care. 2003;7:R7. doi: 10.1186/cc2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Javanainen T, Ishihara S, Gayat E, Charbit B, Jurkko R, Cinotti R, Mebazaa A. Prolonged corrected QT interval is associated with short-term and long-term mortality in critically ill patients: results from the FROG-ICU study. Intensive Care Med. 2019;11:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Noord C, Eijgelsheim M, Stricker BH. Drug- and non-drug-associated QT interval prolongation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.