Abstract

Background

A nationwide investigation on the carriage proportion of H. influenzae among healthy populations is lacking in China. The purpose of the study was to review the prevalence of pharyngeal carriage of H. influenzae among healthy populations in China, and explore its influencing factors. The serotypes distribution of H. influenzae was also analyzed.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted with key words “Haemophilus influenzae”, “Carriage”, and “China” or “Chinese” from inception to March 2018. After careful screening, the data of included articles were extracted with a pre-designed excel form. Then, the pooled carriage proportion of H. influenzae was calculated using the random effect model.

Results

A total of 42 studies with 17,388 participants were included. The overall pooled carriage proportion of H. influenzae was 0.17 (95% CI: 0.13–0.21), and the carriage proportion largely varied by province. Subgroup analysis indicated that the pooled carriage proportion was 0.17 (0.13–0.21) for children, and 0.14 (0.7–0.23) for adults. There were no statistically significant heterogeneity between subgroups by age (p = 0.65), sex (p = 0.88), and season (p = 0.10). The pooled carriage proportion of Hib was 0.01 (0–0.02), while the carriage proportion of NTHi was 0.22 (0.13–0.31).

Conclusion

In China, the carriage proportion of H. influenzae among healthy population was low, but it largely varied by provinces.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-019-4195-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Haemophilus influenzae, Carriage, Healthy population, Meta-analysis

Background

Haemophilus influenzae is a gram-negative coccobacilli including encapsulated strains and unencapsulated strains (nontypeable H. influenzae, NTHi). NTHi is an important pathogen among children that causes otitis media, sinusitis, conjunctivitis, and pneumonia, while in adults, it causes respiratory tract infection primarily in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [1]. Based on the capsular polysaccharide, the encapsulated strains can be separated into 6 serotypes (Hia-f). Hib is a major cause of bacterial meningitis among young children worldwide, before the widespread introduction of Hib vaccines [2]. The colonization of H. influenzae on the upper respiratory tract is a risk factor causing related diseases [3]. Thus, investigating the pharyngeal carriage of H. influenzae among healthy population have potential implications for public health policy.

In China, up to now, many studies investigated the pharyngeal carriage of H. influenzae among healthy populations. For example, Pan and colleagues [4] collected and examined the nasal swabs of 1088 children in Chaoshan region and found that 20 children (0.018) with the colonization of H. influenzae. Zhao and colleagues [5] tested the nasopharyngeal swabs of 472 children aged 2–5 years old in Beijing and found that the carriage proportion of H. influenzae was 0.095. All of these studies were conducted in specific regions and the results of these studies substantially varied, given the vast territory and population of China. The nationwide investigation on the carriage of H. influenzae among healthy people is lacking.

Thus, it is necessary to conduct a systematic review, to clarify the prevalence of H. influenzae nationally and explore the possible determinants of the prevalence of H. influenzae, based on the current evidences available. The present study systematically searched and reviewed the articles regarding the pharyngeal carriage of H. influenzae among healthy populations in China. This will help to describe the prevalence of H. influenzae and its influencing factors, and contribute to the decisions of public health policy.

Methods

Literature search and screening

Four databases (PubMed, CNKI, CBM, and Wanfang) were systematically searched with key words “Haemophilus influenzae”, “Carriage”, and “China” or “Chinese” from inception to March 2018, in order to collect and identify the studies regarding the carriage of H. influenzae among the Chinese population. In addition, the reference lists of selected studies were checked to ensure complete coverage.

The screening of studies was conducted independently by two authors. When there was the disagreement, the two authors discussed the case and came to consensus. The searched studies were imported to the NoteExpress for duplicate checking. After duplicate studies were deleted, the first round screening was conducted based on the title and abstract to excluded irrelevant studies. Then, the full text of remained studies were retrieved for the second round screening based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) observational studies carried out among healthy (without upper respiratory infection) Chinese population residing in mainland China; (2) specimens from nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab; (3) culture-based inspection method of H. influenzae including X + V factor test, PCR, grouping serum, and so on; (4) sufficient information for the calculation of carriage proportion of H. influenzae. Studies only reported the proportion of carriage for single serotype of H. influenzae were excluded. In addition, studies from Hongkong, Macao, and Taiwan were also excluded because of the different immunization programs with mainland. Only the studies published in Chinese and English were included.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The data extraction and quality assessment were also independently extracted by two authors, and consensus was reached by group discussion. The following data were extracted from selected articles: author, publication year, period and region of study, the number and characteristic of participants, inspection method of H. influenzae, and number of participants with H. influenzae. Moreover, the number of participants with the non-capsules type and six serotypes of H. influenzae were also extracted. The risk of bias of selected studies were assessed according to a guideline which was adopted from the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [6] and included five core items: sample population, sample size, participation rate, outcome assessment, and analytical method to control for bias.

Statistical analysis and graphing

The pooled carriage proportion of H. influenzae with its 95% confidence intervals were calculated by using the random effect model. Since the carriage proportion of H. influenzae in multiple studies less than 0.2, the data was converted with the double arcsine method before combination to ensure the 95% confidence intervals of carriage proportion for all included studies belong 0–1. Forest plots were generated to describe the carriage proportion and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each studies and overall estimate. The Q test was used to test the heterogeneity, and I2 statistic was calculated to quantificationally evaluate the heterogeneity (low: 25–50%, moderate: 50–75%, and high: > 75%). To discover potential sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were conducted by age, gender, season, and serotype. To assess the stability of the pooled results, sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding each study at a time. A funnel plot was generated to visually assess the publication bias, and Egger’s test and Begg’s test were also conducted. The pooled carriage proportion of H. influenzae by provinces were calculated, and then a statistical map was generated using an online website for mapmaking (http://c.dituhui.com). All above analyses were conducted in the STATA 13.0 software and the Microsoft Office Excel 2013. The p value ≤0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All the generated pictures were properly modified by using the Adobe Illustrator CS6 software for a better visual effect.

Results

Search results and characteristics of included studies

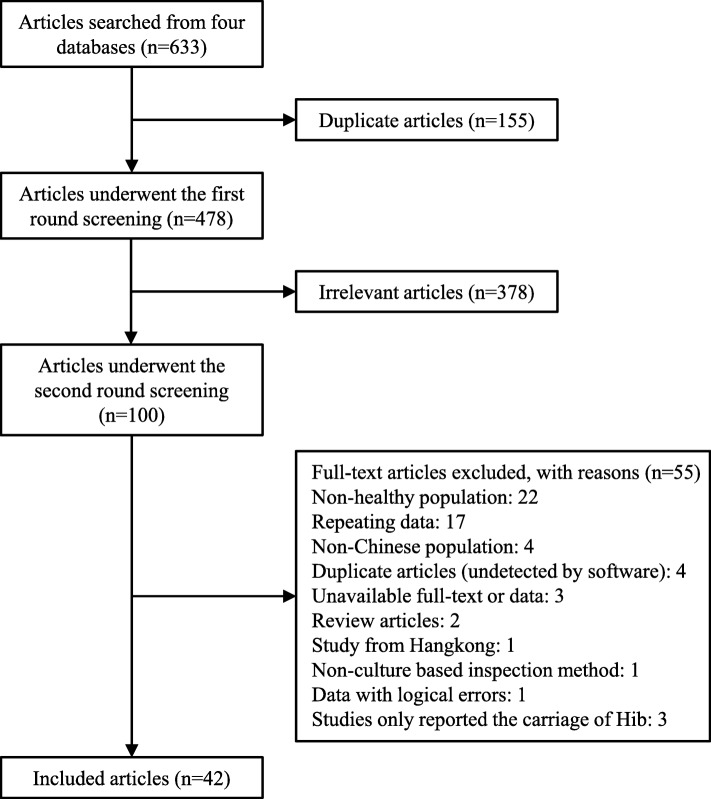

A total of 633 articles were found from aforementioned four databases after the systematic search. 155 duplicate articles were excluded by using the NoteExpress software, and another 378 articles were excluded in the first round screening. Then, the full text of remaining 100 articles were reviewed. Eventually, 42 articles [4, 5, 7–46] with 17,388 participants were included (Fig. 1). No additional articles were identified from the reference lists of included articles.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of articles screening

The main characteristics and results of quality assessment of all included studies were listed in Table 1. The study period of all articles ranged from 1989 to 2013, and the study region covered 11 out of Chinese 31 province-level administrative regions (Excluding studies from Hongkong, Macao, and Taiwan for aforementioned reason).

Table 1.

The characteristics and results of quality assessment of the included studies

| Literature | Period | Region | Sample size | Age of subjects | Inspection methods | Participants with Hi | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu Q, 1993 [7] | 1989–1990 | Beijing | 115 | 2~6y | Culture, Hi grouping serum | 37 | 7 |

| Lai G, 1997 [8] | 1996.01 | Shanghai | 181 | 2~11y | Culture | 49 | 6 |

| Wang G, 1999 [9] | / | Shanghai | 255 | ≤18y | Culture, Hi grouping serum | 66 | 6 |

| Zhang Y, 2000 [10] | 1999 | Zhangjiakou; Hebei province | 319 | 4~60y | Culture | 73 | 7 |

| Chen L, 2000 [11] | / | Wuhan; Hubei province | 52 | / | Culture | 6 | 6 |

| Zhang H, 2001 [12] | 1998–1999 | Fuzhou; Fujian province | 2053 | 3~6y | Culture | 403 | 7 |

| Cao G, 2002 [13] | 2000–2001 | Hangzhou; Zhejiang province | 897 | 4~7y | Culture | 159 | 7 |

| Chen Q, 2002 [14] | 1998–2001 | Nanchang; Jiangxi province | 60 | 1 m-14y | Culture | 1 | 6 |

| Hou A, 2002 [15] | 1995–2000 | Beijing | 307 | ≤13y | Culture | 20 | 7 |

| Luo X, 2002 [16] | / | Zhongshan; Guangdong province | 178 | 18-56y | Culture | 46 | 6 |

| Chen Z, 2002 [17] | / | Hangzhou; Zhejiang province | 37 | 25.8 ± 9.8 m | Culture, PCR | 3 | 6 |

| Zhou H, 2003 [18] | 2001–2001 | Guangzhou; Guangdong province | 150 | 3~5y | Culture | 37 | 6 |

| Zeng Y, 2003 [19] | / | Chongqing | 400 | ≤5y | Culture | 64 | 6 |

| Hua C, 2005 [20] | 2002–2003 | Hangzhou; Zhejiang province | 848 | 2~5y | Culture, Hi grouping serum | 217 | 6 |

| Zhao X, 2005 [21] | 2002 | Zhongshan; Guangdong province | 327 | 6-9y | Culture | 39 | 6 |

| Luo X, 2006 [22] | 2003 | Zhongshan; Guangdong province | 186 | 3-6y | Culture | 45 | 7 |

| Liu L, 2007 [23] | / | Chongqing | 150 | / | Culture | 15 | 7 |

| Lai Z, 2007 [24] | / | Dongguan; Guangdong province | 546 | 4-6y | Culture | 109 | 7 |

| Li R, 2007 [25] | 2001 | Shijiazhuang; Hebei province | 890 | ≤5y | Culture | 139 | 8 |

| Chen D, 2007 [26] | / | Beijing | 561 | 3-6y | Culture | 134 | 6 |

| Wu T, 2007 [27] | 2006–2006 | Danyang, Binhai; Jiangsu province | 656 | ≤5y | Culture, PCR | 389 | 7 |

| Dong H, 2008 [28] | 2005–2005 | Shanghai | 501 | 60-92y | Culture | 38 | 7 |

| Wang F, 2009 [29] | 2007–2008 | Jianggan; Zhejiang province | 101 | ≤5y | Culture, Hi grouping serum, PCR | 21 | 7 |

| Sun J, 2009 [30] | 2008–2008 | Shenzhen; Guangdong province | 380 | all ages | Culture, PCR | 121 | 8 |

| Chen H, 2009 [31] | / | Shenzhen; Guangdong province | 181 | 3~6y | Culture | 45 | 6 |

| Ye J, 2009 [32] | 2007–2008 | Changshan, Dongyang, Jianggan; Zhejiang province | 301 | ≤5y | Culture, Hi grouping serum | 43 | 7 |

| Meng X, 2009 [33] | / | Shenzhen; Guangdong province | 360 | 3-7y | Culture, Hi grouping serum | 90 | 7 |

| Zhang J. 2010 [34] | 2009 | Quzhou; Zhejiang province | 70 | 3-5y | Culture, Hi grouping serum | 12 | 6 |

| Li Y, 2010 [35] | 2008 | Dongyang; Zhejiang province | 238 | ≥6 m | Culture, Hi grouping serum | 21 | 6 |

| Wang J, 2010 [36] | 2007–2009 | Weihai; Shandong province | 820 | / | Culture | 98 | 6 |

| Zhang L, 2011 [37] | / | Dongguan; Guangdong province | 600 | 12-18 m | Culture | 25 | 7 |

| Di M, 2012 [38] | 2010–2011 | Dongcheng; Beijing | 834 | 1–12y | Culture, Hi grouping serum | 73 | 7 |

| Ye Y, 2012 [39] | / | Jinshan; Shanghai | 390 children & 240 elders | ≤14y & 60-80y | Culture | 82 | 7 |

| Ping G, 2013 [40] | 2009–2010 | Xuanwu; Beijing | 600 | 12-18 m | Culture | 27 | 7 |

| Zhai R, 2013 [41] | / | / | 158 | 20-34y | Culture | 8 | 6 |

| Qiao H, 2013 [42] | 2010 | Zhangjiakou; Hebei province | 100 | 3-5y | Culture, PCR | 31 | 6 |

| Chen X, 2013 [43] | / | / | 400 | / | Culture | 125 | 6 |

| Wang Y, 2013 [44] | / | Baoding; Hebei province | 162 | all ages | Culture, Real-time PCR | 62 | 8 |

| Xiong W, 2014 [45] | 2013 | Chongqing | 150 | ≤6y | Culture | 11 | 6 |

| Zhai R, 2014 [46] | / | / | 70 | 17-32y | Culture | 11 | 6 |

| Zhao X, 2015 [5] | 2012–2013 | Huairou; Beijing | 472 | 2–5y | Culture | 45 | 6 |

| Pan H, 2016 [4] | 2010–2011 | Chaoshan; Guangdong province | 1088 | 2-6y | Culture | 20 | 8 |

/: The information were not described. PCR: Polymerase chain reaction

Overall pooled pharyngeal carriage of H. influenzae among healthy population

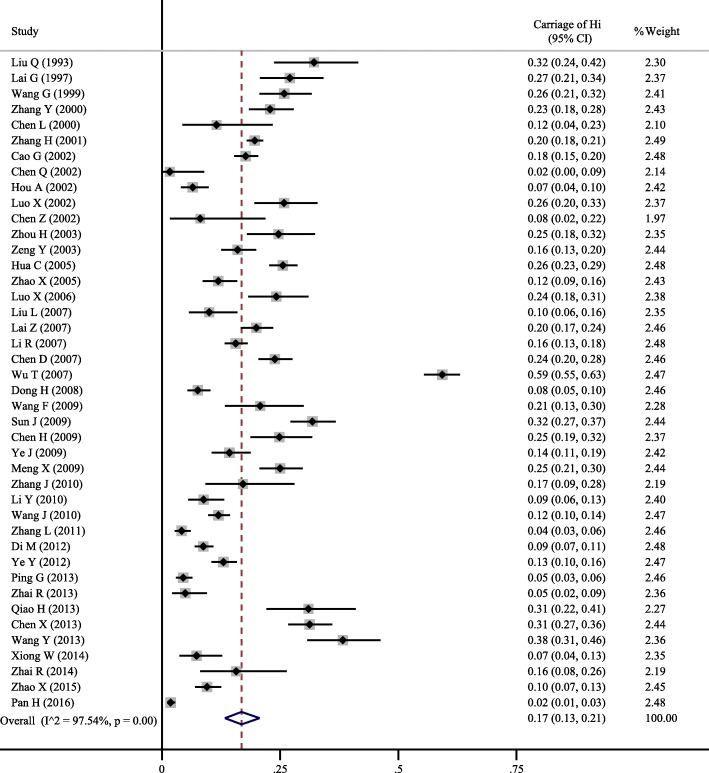

A total of 42 studies [4, 5, 7–46] including 17,388 participants reported the carriage proportion of H. influenzae, and the overall pooled proportion of carriage was 0.17 (95% CI: 0.13–0.21) with significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 97.54%, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2; Additional file 1).

Fig. 2.

The overall pooled carriage proportion of Hi (H. influenzae) among healthy population

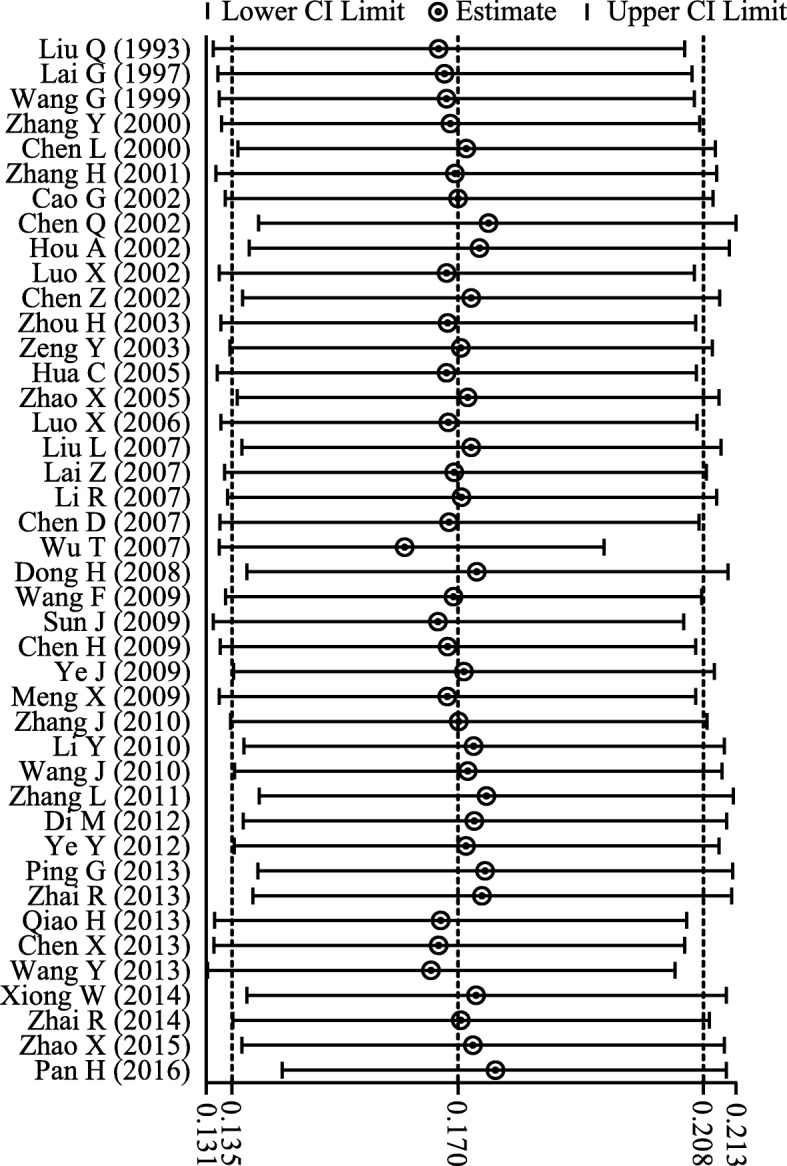

The result of sensitivity analysis showed that the pooled carriage proportion varied from 0.161 (0.133–0.193) (When Wu [27] was excluded) to 0.176 (0.143–0.212) (When Pan et al. [4] was excluded), and indicated that the stability of overall carriage proportion of H. influenzae was not influenced by a single study (Fig. 3; Additional file 2).

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity analysis for the effect of individual studies (given named study in the Y axis is omitted) on the pooled carriage proportion

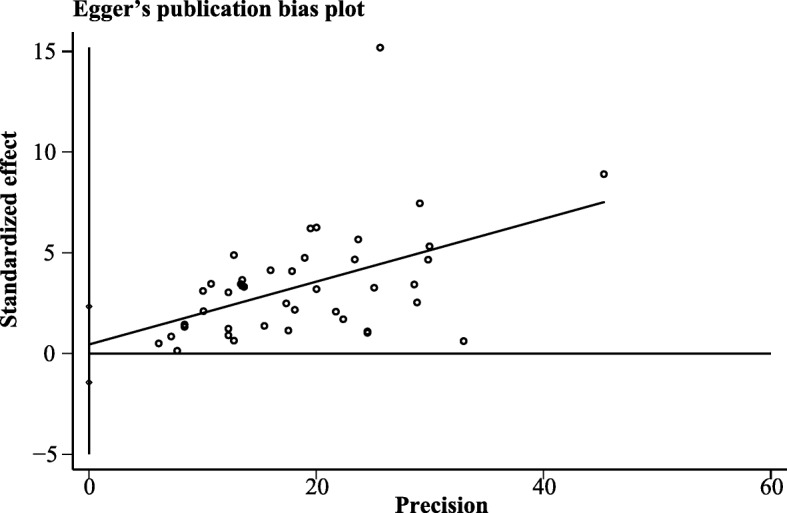

Egger’s publication bias plot was generated, and the visual symmetry of the funnel plot suggested that there was minimal publication bias (Fig. 4). Moreover, both of the results of Egger’s test (p = 0.63) and Begg’s test (p = 0.46) also indicated that there was mimimal potential risk of publication bias.

Fig. 4.

The Egger’s funnel plot of the 42 included studies in the meta-analysis

Subgroup analyses

Among the 42 studies [4, 5, 7–46], 31 studies [4, 5, 7–9, 11–15, 17–27, 29, 31–34, 37, 38, 40, 42, 45] examined children and 5 studies [16, 28, 41, 43, 46] examined adults. Two studies [10, 39], that included both children and adults, were separated at 18 years old and then split into the different subgroups. The rest of 4 studies [30, 35, 36, 44] were not included in the subgroup analysis because of the insufficient age information of participants. The pooled carriage proportion of H. influenzae was 0.17 (0.13–0.21) for children (n = 14,137), and 0.14 (0.07–0.23) for adults (n = 1651). There was no significant heterogeneity between subgroups by age (p = 0.65), while significant heterogeneity within subgroups were found (Children: I2 = 97.79%, p < 0.01; Adult: I2 = 95.26%, p < 0.01).

A total of 12 studies [5, 7, 13, 21, 22, 25–27, 30, 31, 39, 44] described the gender-specific carriage proportion of H. influenzae, and the pooled carriage proportion was 0.25 (0.16–0.35) for male (n = 2506), and 0.24 (0.19–0.31) for female (n = 2531), without significant heterogeneity between subgroups (p = 0.88). Six studies [7, 12, 33, 37, 38, 40] described the season-specific carriage proportion of H. influenzae, and the pooled carriage proportion was 0.10 (0.06–0.17) in spring (n = 1077), 0.08 (0.03–0.14) in summer (n = 1459), 0.14 (0.11–0.16) in autumn (n = 743), and 0.24 (0.11–0.40) in winter (n = 1283), without significant heterogeneity between subgroups (p = 0.10).

A total of 8 studies (n = 1867) [9, 29, 30, 32–35, 44] described the carriage proportion of specific serotypes, and the pooled carriage proportion of NTHi, Hib, and other serotypes (a, c, d, e, and f) were 0.22 (0.13–0.31), 0.01 (0–0.02), and 0 (0–0.01), respectively.

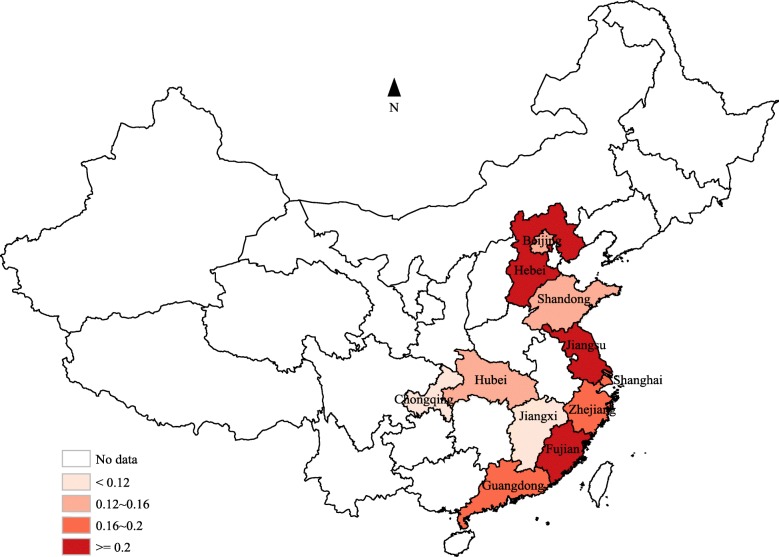

A total of 39 studies [3, 4, 6–26, 28–40, 42, 44, 45] described their study region, which covered 11 province-level administrative regions. The carriage proportion of H. influenzae by provinces varied from 0.02 (0–0.09) in Jiangxi to 0.59% (0.55–0.63) in Jiangsu (Fig. 5; Additional file 3). The heterogeneity between subgroups by province was statistically significant (p < 0.01), while the heterogeneity within subgroups were also statistically significant (I2: 88.22%~ 98.19%, all p < 0.01).

Fig. 5.

The pooled carriage proportion of H. influenzae by province

Discussion

Globally and in China, most of the studies regarding the carriage of H. influenzae were focused on children, which contained substantially different results. For example, in Italy, a study including 717 healthy children aged < 6 years old found that the oropharyngeal carriage proportion of H. influenzae was 0.14 [3], while a study of Spain found that the carriage proportion was 0.42 among 900 healthy < 5-year-old children [47], and a study in Belgium indicated the carriage proportion was as high as 0.83 among 333 healthy children [48]. Results of the meta-analysis indicated that the pooled carriage proportion of H. influenzae among Chinese healthy children was 0.17 (0.13–0.21), which was a relatively low level. But as presented in Fig. 5, the carriage proportion of H. influenzae largely varied by province (0.02–0.59). Since almost all available studies were conducted in limited regions (usually within single city), the differences between provinces has not be previously reported. A possible reason of the variations between provinces might be the insufficient number of studies, which results in unstable results. The available studies only covered 11 in 31 provinces of China, and only single study was available for 5 of those 11 provinces. For 6 provinces with 3 or more studies available, the pooled carriage proportion ranged from 0.11–0.26, which was more stable compared to the range of 11 provinces (0.02–0.59). Moreover, only provinces in the eastern part of China were available. Our results indicated significant between-provinces differences exist, which might influence clinical decision of related diseases according to the actual prevalence of H. influenzae in different localities. In particular, no data exists for the western and northern parts of China.

The significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 97.54%, p < 0.01), was not explained by the subgroup analysis by age, gender, and season. For age, a possible reason of statistically insignificant between-subgroup heterogeneity was cursory grouping. Because of insufficient age information or inconsistent age grouping in included studies [4, 5, 7–29, 31–34, 37–43, 45, 46], these studies were simply divided into only two subgroups at 18 years old, which might confound the variation of H. influenzae carriage proportion with age. For gender, none of the included studies [5, 7, 13, 21, 22, 25–27, 30, 31, 39, 44] reported a statistically significant difference of carriage proportion between males and females, which were consistent with several studies in the United States [49], in Spain [47], and in Italy [3]. It is reasonable to conclude that the gender might not play a role on the carriage of H. influenzae. For seasonality, the heterogeneity between subgroups (p = 0.10) might be explained by inconsistent sampling time and other confounding factors, since the statistically significant difference between seasons were reported in multiple included studies [12, 33, 38, 40].

The serotype distribution of H. influenzae was analyzed in this meta-analysis. Different from the countries which introduced the Hib vaccines in which the Hib was hardly detected [3, 47, 49, 50], results of the present meta-analysis indicated that the carriage proportion of Hib among Chinese healthy population was 0.01, which was lower than a previous meta-analysis study indicating the carriage proportion of Hib for healthy children in China was 0.06 [51]. The reason for the lower carriage proportion in our study could be that we excluded studies that only reported the carriage proportion of Hib. The including of Hib vaccines into the national immunization program should be considered in China, or at least, in some provinces with higher carriage proportion of Hib. Our results indicated that the carriage proportion of NTHi was 0.22 among Chinese healthy population, which makes it a public health issue worthy of attention. It has been reported that the NTHi was frequently identified as the pathogenic bacteria for otitis media, pneumonia, sinusitis [1, 52].

There were some limitations in this meta-analysis. First, the difference of precision of inspection, a possible important reason which influence the detection results of carriage of H. influenzae, was unable to be analyzed in this meta-analysis. The precision of inspection would be affected by various factors including the way of swabbing, the time until culturing, the laboratory conditions, the operation of staff, storage and transportation of specimen, and others. These factors were unable to be collected from included articles. Secondly, the meta-regression was not performed because of the needed information was unavailable.

Conclusion

In China, the pharyngeal carriage proportion of H. influenzae among healthy population was at a relatively low level, but it largely varied by study region. Therefore, well-designed nationwide survey with uniform sampling and inspection method on the carriage proportion of H. influenzae among healthy population, especially in children, is urgently needed, to clarify the actual prevalence of H. influenzae in China, which will contribute to the decision on the prevention and control strategies of related diseases.

Additional files

Data collection form and the result of collection. (XLSX 24 kb)

Result of sensitivity analysis. (XLSX 14 kb)

The pooled carriage proportion of H. influenzae by province. (XLSX 8 kb)

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Jay Maddock for his work on language editing.

Abbreviations

- H.

Haemophilus

- Hib

Haemophilus influenzae type B

- NTHi

Non-typeable Haemophilus Influenza

- STROBE

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

Authors’ contributions

JZ and PY designed the study and drafted an outline. JZ participated in data analysis, PY draft of initial manuscript, AP revised the manuscript and all of authors approved the final content off this manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript was funded by Health Commission of Wuhan Municipality Project (No WX17A04).The funders had role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

We declare that the data supporting the conclusions of this article are fully described within the article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Peng Yang and Jieming Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Peng Yang, Email: 1583768106@qq.com.

Jieming Zhang, Email: 703875264@qq.com.

Anlin Peng, Email: 13531154018@163.com.

References

- 1.Murphy TF, Faden H, Bakaletz LO, et al. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae as a pathogen in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:43–48. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318184dba2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peltola H. Worldwide Haemophilus influenzae type b disease at the beginning of the 21st century: global analysis of the disease burden 25 years after the use of the polysaccharide vaccine and a decade after the advent of conjugates. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:302–317. doi: 10.1128/CMR.13.2.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giufre M, Daprai L, Cardines R, et al. Carriage of Haemophilus influenzae in the oropharynx of young children and molecular epidemiology of the isolates after fifteen years of H. influenzae type b vaccination in Italy. Vaccine. 2015;33:6227–6234. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan H, Cui B, Huang Y, Yang J, Ba-Thein W. Nasal carriage of common bacterial pathogens among healthy kindergarten children in Chaoshan region, southern China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:161. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao X, Li C, Liu L, et al. Nasopharyngeal carriage of Haemophilus influenzae in 2-5 years old children in Huairou District of Beijing and study on safety of related vaccine. Occup Health. 2015;31(20):2859–2861. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology. 2007;18:805–835. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Q, Gao W, Li Y, et al. Study on oral pharyngeal carriage of Haemophilus influenzae of healthy children in Beijing. Chin J Epidemiol. 1993;14:136–138. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai G, Ye L, Li Y, et al. A clinical survey on lower respiratory tract infections caused by Haemophilus influenzae in children. Chin J Pediatr. 1997;35:31–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang G, Luo W, Xiu Q, et al. Study on serotyping of Haemophilus influenzae and the positive rates ofβ-lactamase. Chin J Tubere Respir Dis. 1999;22:8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Ji J, et al. Survey on the carriage of Haemophilus influenzae among healthy people. Chin J Publ Heal. 2000;16:51–52. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L, Zhou L, Zhu Q, et al. The analysis of Haemophilus carriage in upper respiratory among healthy children. Chin J Microecol. 2000;12:43+47. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H, Ye L, Chen X, et al. Study on Haemophilus influenzae carriage and antimicrobial susceptibility among health preschool children. Chin J Pediatr. 2001;39:360–361. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao G, Cao H, Cheng Y, et al. Investigation of Hemophilus carrying rate in pharyngeal site in healthy children. Zhejiang Prev Med. 2002;11:4–5 in Chinese.

- 14.Chen Q, Duan R, Liu J, et al. A clinical and pathogen study on Haemophilus influenzae infection of children. Jiangxi Med J. 2002;37:91–94. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01169-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou A, Liu Y, Xin D, et al. Nasopharyngeal carriage status of common pathogenic microorganisms in healthy children and its clinical significance. Chin J Pediatr. 2002;40:48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo X, Feng X, Li Z, et al. Investigation on the status of nasopharyngeal bacteria carriers in medical staff. Chin J Microecol. 2002;14:40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z, Wang T, Shang S, et al. Study on application of PCR in the diagnosis of Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia. J Zhejiang Univ (Med Sci) 2002;31:50–53. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2002.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou H, Deng L, Deng Q, et al. Study on nasopharyngeal carriage and antimicrobial susceptibility of Haemophilus influenzae among children in Guangzhou. Chin J Prac Pediatr. 2003;18:626–627. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng Y. Investigation of the carriage rate and resistance of pharyngeal HIN in healthy children in Chongqing. World J Med Today. 2003;4:13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hua C, Sun L, Li J, et al. Carriage and serotypes of Haemophilus influenza in young children attending a kindergarten in Hangzhou. Chin J Lab Med. 2005;28:389–391. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao X, Zhao Z, Lin P, et al. Bacteria survey of 327 throat swabs specimens in healthy primary school children. Chin J Misdiagn. 2005;5:378–379. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo X, Liang J, Gao S, et al. Surveys on bacteria nasopharyngeal carriage prevalence in 186 children. Chin J Microecol. 2006;18:204–205+208. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Xie W, Jing C. Survey of respiratory tract microbial population in children. Chin J Microecol. 2007;19:22–24+26. doi: 10.1097/00029330-200701010-00005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai Z, Zhang L, Liu Y, et al. Study on drug susceptibility of Haemophilus influenzae from children of Dongguan district. J Bethune Mil Med Coll. 2007;5:133–134. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li R, Liu S, Liu D, et al. Research of Haemophilus influenza’s population carriage in children under the age of 5 years old. Mod Prev Med. 2007;34:135–137. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen D, Hu J, Xu H, et al. To investigate the carriage drug resistances and serotype of Haemophilus in the upper respiratory tract among healthy children. Chin J Epidemiol. 2007;28:1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu T. The infection of Haemophilus influenzae and natural immunity antibody level researches on healthy children in partial Jiangsu province. Vol Master: Nanjing Medical University, 2007:68 (in Chinese).

- 28.Dong H, Cheng M, Gu J, et al. Or0pharyngeal bacterial carriage in eldery. Chin Gen Prac. 2008;11:912–913+922. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang F, Xu D, Xu B, et al. A screening on the carrier of Haemophilus influenzae in healthy children. Dis Surveill. 2009;24:498–500. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun J, Wen Q, Duan Y, et al. Study on the status of oral pharyngeal carriage and typing of Haemophilus influenza in healthy preschool in Shenzhen. Chin Trop Med. 2009;9:1888–1890. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H, Huang R, Yuan Y, et al. Haemophilus influenza -carrying rate of preschool age children in Shenzhen and results of drug resistance. Chin Trop Med. 2009;9:322–323. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye J, Mei L, Luo Y, et al. Study on carriage status and typing of Haemophilus influenzae among children in Zhejiang, 2007-2008. Dis Surveill. 2009;24:782–785. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meng X. Study on the infection status and drug resistance of Haemophilus influenzae in preschool children in a certain city. Vol. Master: Central South University, 2009:38 (in Chinese).

- 34.Zhang J, Wang F, Yang R. Study on carriage status and etiology of Haemophilus influenzae among healthy children in Quzhou city. Chin J Health Lab Technol. 2010;20:2583–2584. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Wang F, Wei J. Analysis of Haemophilus influenzae carrying status and drug resistance in Dongyang city. Zhejiang Prev Med. 2010;22:37–38. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, Yu C, Zhang S. Study on distribution and drug sensitivity of Haemophilus influenza in normal population. China Mod Med. 2010;17:131–132. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Li H, Yuan D, et al. Study on the population carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis in children at the age of 12~18 months in Dongguan city. Chin J Health Lab Technol. 2011;21:496–498. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di M, Huang H, Lu M, et al. Carriage of Haemophilus influenzae among healthy children aged 1-12 years in Dongcheng district, Beijing. Dis Surveill. 2012;27:720–722. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ye X, Zhu J, Lu A, et al. Analysis of the carrier rate and antibiotic resistance of Haemophilus influenzae in healthy children and aged people in Jinshan district of Shanghai. Chin J Health Lab Technol. 2012;07:1708–10 in Chinese.

- 40.Ping G, Liu Z, Wang Q, et al. Investigation on nasopharyngeal carriage rate of streptococcus pneumonia, haemophilus influenzae and moraxella catarrhalis in healthy infants in Xuanwu district in Beijing. Mod Med Heal. 2013;29:3245–3246+3249. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhai R, Hu W, Xu H, et al. Detection of colonization bacteria in the throat of border soldiers in northeast region and analysis of drug resistance. J Prev Med Chin PLA. 2013;31:326–327. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiao H, Zhang Y, Chang Y, et al. Carrying rate and the epidemic characteristics of Haemophilus influenzae isolated from healthy children in Zhangjiakou. Mod Prev Med. 2013;40:3273–3276+3283. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen X. Comparison and analysis of pre-practice and post-practice nasopharyngeal infections in nursing students in colleges and universities. Health Vocat Educ. 2013;31:120–121. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y. Survey on carriage of Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae among healthy population in Hebei province. Vol. Master: Chinese Center For Disease Control And Prevention, 2013:101(in Chinese).

- 45.Xiong W. The analysis of common pathogen in children’s pharynx. Lab Med Clin. 2014;11:477–479. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhai R, Li Y, Zhang H, et al. Analysis of bacterial distribution and drug resistance in throat of a soldier in winter and spring. Clin J Med Offic. 2014;42:1313–1314. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puig C, Marti S, Fleites A, et al. Oropharyngeal colonization by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae among healthy children attending day care centers. Microb Drug Resist. 2014;20:450–455. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jourdain S, Smeesters PR, Denis O, et al. Differences in nasopharyngeal bacterial carriage in preschool children from different socio-economic origins. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:907–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lowther SA, Shinoda N, Juni BA, et al. Haemophilus influenzae type b infection, vaccination, and H. influenzae carriage in children in Minnesota, 2008-2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:566–574. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811000793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oikawa J, Ishiwada N, Takahashi Y, et al. Changes in nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis among healthy children attending a day-care Centre before and after official financial support for the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and H. influenzae type b vaccine in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2014;20:146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Y, Pan X, Cheng W, et al. Haemophilus influenzae type b carriage and burden of its related diseases in Chinese children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2017;35:6275–6282. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Block SL, Hedrick J, Harrison CJ, et al. Community-wide vaccination with the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate significantly alters the microbiology of acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:829–833. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000136868.91756.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data collection form and the result of collection. (XLSX 24 kb)

Result of sensitivity analysis. (XLSX 14 kb)

The pooled carriage proportion of H. influenzae by province. (XLSX 8 kb)

Data Availability Statement

We declare that the data supporting the conclusions of this article are fully described within the article.