Abstract

Introduction

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is one of the most critical indicators determining the clinical outcome of paediatric intensive care patients. Clinical decision support systems (CDSS) can be designed to support clinicians in detection and treatment. However, the use of such systems is highly discussed as they are often associated with accuracy problems and ‘alert fatigue’. We designed a CDSS for detection of paediatric SIRS and hypothesise that a high diagnostic accuracy together with an adequate alerting will accelerate the use. Our study will (1) determine the diagnostic accuracy of the CDSS compared with gold standard decisions created by two blinded, experienced paediatricians, and (2) compare the system’s diagnostic accuracy with that of routine clinical care decisions compared with the same gold standard.

Methods and analysis

CADDIE2 is a prospective diagnostic accuracy study taking place at the Department of Pediatric Cardiology and Intensive Care Medicine at the Hannover Medical School; it represents the second step towards our vision of cross-institutional and data-driven decision-support for intensive care environments (CADDIE). The study comprises (1) recruitment of up to 300 patients (start date 1 August 2018), (2) creation of gold standard decisions (start date 1 May 2019), (3) routine SIRS assessments by physicians (starts with recruitment), (4) SIRS assessments by a CDSS (start date 1 May 2019), and (5) statistical analysis with a modified approach for determining sensitivity and specificity and comparing the accuracy results of the different diagnostic approaches (planned start date 1 July 2019).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was obtained at the study centre (Ethics Committee of Hannover Medical School). Results of the main study will be communicated via publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03661450; Pre-results.

Keywords: clinical decision support systems, clinical trial, systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Related studies reached successful results in the context of clinical decision-support systems (CDSS) for systemic inflammatory response syndrome detection, but due to the study design, the reported results often do not reflect the usefulness of such systems in routine clinical care.

We present an adjusted and novel approach for the design and the statistical analysis of diagnostic studies for CDSS from a more routine clinical care perspective, because our study comprises (1) the validation of the CDSS in comparison to the assessment of two experienced clinicians by blinded chart review (gold standard) and (2) the comparison of the system’s diagnostic accuracy with the diagnostic accuracy of real-time assessments by clinicians working in routine clinical care and manually evaluating patients.

Although our study does not comprise specific evaluations of CDSS user acceptance, it is suited to present the potentials of CDSS use in routine clinical care and, thus, to foster the willingness to trust the system in future.

Introduction

The first definition of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and sepsis was made by the members of the ‘American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference Committee’ in 1992. SIRS was described as a ‘systemic inflammatory response to a variety of severe clinical insults’; sepsis on the other hand was ‘the systemic response to infection’.1 The criteria have been adapted to paediatric patients by the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference (IPSCC) in 2005.2 According to this, SIRS was present if the patient presented two or more of the defined age-dependent criteria (at least an abnormal core temperature or leucocyte count). The other criteria include abnormal heart rate and respiratory rate. According to the IPSCC, sepsis is defined as SIRS in the presence of or as a result of suspected or proven infection. Although the definition of SIRS is no longer taken into account for the sepsis diagnosis in adult medicine, it is still relevant in paediatric medicine. Paediatric patients with SIRS and sepsis are known to have a higher risk of morbidity and mortality.3–6 SIRS in paediatric patients also causes a significantly prolonged stay in intensive care after cardiothoracic surgery7 and entails an increased probability of organ dysfunctions.8

Independent of the underlying disease and together with SIRS and sepsis, organ dysfunction and failure represent the critical determinants of patient outcome in both adult and paediatric medicine. Prevention and rapid effective treatment of multiorgan dysfunction and failure are crucial for survival. An optimisation of the diagnostic and therapeutic workflow is likely to have an immense impact on clinical outcome of critically-ill patients. In paediatric septic shock patients, every hour without appropriate treatment was associated with an increased chance of death by 40%.9 Conclusively, early recognition and treatment of paediatric SIRS and sepsis are vital.10

To assure that patients are treated with the best available approaches, evidence-based medicine11 together with personal expertise represent the current gold standard of medical patient management. However, clinicians are often confronted with a stressful environment, which fosters decision-making with a lower quality than aspired.12 This is particularly true for paediatric intensive care units (PICU), in which clinicians work under challenging conditions characterised by a high degree of dynamics, uncertainty and risk, time pressure and a vast amount of data. Altogether, these factors carry risk for medical errors and adverse effects on patient safety.13–15

To tackle these challenges, clinicians can be supported by clinical decision-support systems (CDSS). The growing digitalisation in medicine involves an immense amount of highly heterogeneous data sets carrying the potential to be valuable for other purposes than initially expected (secondary use of data); the design of systems that are able to efficiently reuse and assimilate routine data, and thereby making data meaningful for clinical care, is fostered. CDSS are shining examples for systems processing clinical and non-clinical data and delivering an added value by detecting diseases, recommending therapies or uncovering yet unknown disease patterns.16 Particularly in sophisticated intensive care settings, the use of highly developed patient data management systems (PDMS) allows the continuous recording of multiple clinical parameters and make high quality data available.

In our previous work, we designed a rule-based and interoperable CDSS for the detection of SIRS in paediatric intensive care.17 The CDSS is able to retrieve and evaluate dynamic facts as routinely and automatically measured parameters from the bedside monitors to detect SIRS episodes. However, only when used in routine clinical care, the benefits can be translated into clinical care. Consequently, an extensive evaluation of the system’s diagnostic accuracy is needed to assure that users will trust the system. This need is even aggravated in our context, because we strive for (1) using an automatic SIRS labelling to train machine learning algorithms, and (2) reaching a self-learning system able to continuously process data and optimise its algorithms when used in routine care (Learning Healthcare System).18 In our previous work, we describe this approach for CDSS design, in which we denote the conduction of such a study as second important step towards the vision of cross-institutional and data-driven decision-support for intensive care environments (CADDIE2).18

Related studies already reached satisfying results.19–21 However, due to the study designs, the reported results might not reflect the usefulness of the CDSS in routine clinical care. Often, the coding of diagnoses as ICD (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) is used as gold standard against which the system’s results are compared with. However, in ICD, episodes of SIRS and sepsis are not documented detailed enough; for example, the time of occurrence is not described. Even though sometimes additional scores are used, not all relevant SIRS episodes can be reflected. Hence, systems evaluated with such an approach in fact have been successfully trained, but with respects to the ICD documentation and not routine decision-making. Additionally, the study population is often very preselected and requires a complete data set of all parameters required as input for the algorithm used. Such perfect data sets are often not available in clinical routine settings.

The exploration of factors influencing a successful CDSS implementation is a ubiquitous topic. In a recent literature review, Kilsdonk et al 22 identified such factors for guideline-based CDSS implementation. One of the aspects reported mostly deals with the information quality of the system and covers the relevance of data and messages delivered by the system.22 This finding relates to a well-known and obviously still unsolved issue called ‘alert fatigue’.23 Other recent work published by Liberati et al 24 describe the conduction of a qualitative study to identify different clusters of attitudes and barriers towards CDSS implementation. The authors describe that, together with a poor integration in the clinical workflow, the ‘fear of experiencing excessive number of alerts’24 is one of the factors hindering the willingness to trust systems and to believe in their unforeseen opportunities (mutual adjustment). This step is declared as one of the most challenging obstacles in CDSS adoption. It is suggested to integrate and evaluate the CDSS in routine clinical care and with real users to overcome these limitations.24

Against the background of our CADDIE objectives and the findings on successful CDSS implementations, we conclude that there is a need for a CADDIE2 trial focusing on validating the CDSS for SIRS and sepsis detection in routine clinical care.

Study objectives and diagnostic approaches

The primary goal is the evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of the CDSS for detecting SIRS in PICU patients (diagnostic approach I), in comparison to the assessments of two clinicians by blinded chart review. In case of disagreement, a third clinician will be consulted. The expert assessments will be treated as gold standard and contain retrospective, extensive data analyses. These comprise evaluating all patients’ measurements, not restricted to the SIRS parameters, including additional values for vital signs validated hourly by the attending nurse.

The secondary goal is to compare the diagnostic accuracy of the CDSS for detecting SIRS in PICU patients evaluated against this gold standard, to the diagnostic accuracy of routine assessments of different clinicians working in routine clinical care (diagnostic approach II) when compared with the same gold standard.

Trial design and study setting

The CADDIE2 study is designed as a single-arm, controlled, prospective diagnostic accuracy study. Single study centre is the Department of Pediatric Cardiology and Intensive Care Medicine at the Hannover Medical School (monocentric). The estimated study duration is 1 year. Our study does not contain comparisons between different patient populations (single-arm) or interventions (no randomisation). Each patient will be assessed by both diagnostic approaches.

Methods and analysis

Preceding studies

We can take advantage of the results of a randomised controlled trial (RCT) with 807 PICU patients from the same ward for the planned study. The expected SIRS prevalence on admission to PICU was reported as 5/100; 20%–10% of the patients developed SIRS later on during their PICU stay.25 Furthermore, we conducted a proof-of-concept study focusing on the technical practicability of the CDSS, yielding at promising results for both the technical infrastructure and the accuracy of the system (sensitivity of 1.00, specificity of 0.94).17

Recommendations and guidelines

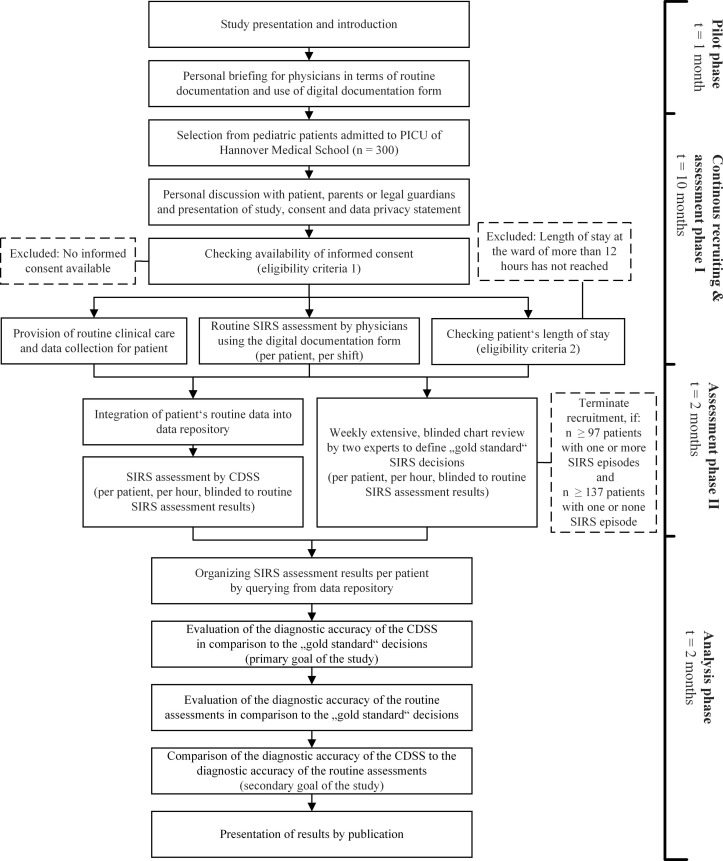

We reviewed work on study planning, national recommendations and templates of ethics committees and associations, and followed the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) in non-drug trials. We designed our study in accordance with the ‘Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies’ (STARD)26 and the ‘Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials’ (SPIRIT)27 guidelines (see figure 1, see online supplementary file 1).

Figure 1.

Time schedule and study episodes for CADDIE2 trial.

bmjopen-2019-028953supp001.pdf (44.4KB, pdf)

Patient population and eligibility criteria

All paediatric patients aged 0 to 18 years admitted to the study centre—independent of the gender, the underlying disease or the time of admission—will be asked for their consent to participate. Patients will be recruited continuously and included, if a positive consent is available; and their length of stay exceeds 12 hours because any patient developing SIRS will not be discharged earlier.

The physicians are specialised paediatricians with experience in paediatric intensive care. There are always one experienced (working in this PICU for over a year) and one less experienced physician (working in this PICU for less than a year) in charge. The reviewers who will perform the manual chart review for creating gold standard decisions are specialised paediatricians and very experienced (working in this PICU for over 3 years), able to discriminate unsound and missing data.

Outcome measures

Sensitivity and specificity on the level of patients will be used as primary outcome measures. As second outcome measure, sensitivity and specificity also can be determined on the level of intensive care days.

Statistical analysis and sample size calculation

For the primary outcome measure, sensitivity and specificity will be determined together with Wald confidence intervals (CI). The comparison will be carried out by comparing the lower bound of the CI with the null hypothesis (which is, as described below in the sample size calculation paragraph, a sensitivity of 0.90 and a specificity of 0.80). If the lower bound of the 95% CI for sensitivity and specificity are both above the values of the predefined null hypotheses, we will reject the null hypotheses. For the secondary outcome measure, sensitivity and specificity will be determined together with CI based on general estimating equations. Additionally, for the secondary goal of comparing the diagnostic accuracy of the CDSS to the one of routine decisions (both when evaluated against the gold standard), sensitivity and specificity values will be compared by means of McNemar tests and CI constructed based on general estimating equations.

All analyses will be accompanied by secondary subgroup analyses, stratified for example, by patients’ age, type of shift and clinical picture associated with SIRS detection (including SIRS, sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock). Factors that might modify the diagnostic accuracy of the CDSS will thus be evaluated in an exploratory way, allowing a better understanding of potential limitations of the system. SIRS prevalence and incidence will be monitored throughout the pilot phase and the main phase of the study, and will be compared with prestudy values in order to estimate the risk of a training effect on physicians’ real-time diagnoses caused by knowledge about the aims of this study.

For analysing the primary outcome measure, the assessment is carried out on the patient level. This is challenging since the assessment is not cross-sectional (as, eg, if the unit of assessment would be an hour respectively a shift) but needs to incorporate the complex longitudinal course of potential assessments within one patient. It is, however, the clinically most meaningful and the most conservative approach for estimating the diagnostic accuracy if conducted correctly. In our case, the entire period of stay is considered and information are aggregated on the patient level. Every person contributes (given that a correct diagnosis is restricted to the period of an hour respectively a shift) parts of its period of stay to the calculation of specificity independently of if the gold standard recorded a SIRS at some point since everybody will have periods without SIRS diagnosis (which need to be classified as well correctly by the CDSS). This leads to situations, which cannot be represented in only one cell of a contingency table. The classical four cases are amended by a new case, which occurs because the CDSS should assess the occurrence of a SIRS event with a correct timing (eg, SIRS event is identified within the correct hour respectively shift). For example, this fifth case prevents that alert firings on day 30 of the intensive care stay will be evaluated as true positives if the gold standard reports a SIRS episode on day 2. Here, the CDSS did not identify the SIRS episode within the correct timing. Thus, this case is used for the determination of both false positives (day 30, contributing to specificity) and false negatives (day 2, contributing to sensitivity). Hence, the fifth case (false positive and false negative) can be defined as follows: the gold standard reports at least one SIRS episode, and the CDSS detect SIRS episodes but (at least one) not within the same hour respectively shift. All other cases are defined as usual (eg, false positive: the gold standard reports no SIRS episode but the CDSS detects one or multiple SIRS episodes).

Based on the different cases, the sensitivity and the specificity will be determined independently. For sample size calculation, the results of the proof-of-concept study were used as a basis (sensitivity 1.00 and specificity 0.94, when calculating on the level of days). For this study with the modified statistical analysis approach, a sensitivity of 90% (alternative hypothesis: 0.98, null hypothesis: 0.90) and a specificity of 80% (alternative hypothesis: 0.90, null hypothesis: 0.80) were chosen as a clinically relevant diagnostic accuracy, with a given accuracy of estimate of 95% (type I error=0.05) and a power of 90% (χ2 test). Consequently, 97 patients suffering from at least one SIRS episode (for the estimation of sensitivity) as well as 137 patients with or without SIRS episodes are required (for the estimation of specificity). Based on the expected incidence and prevalence, at least 300 patients need to be considered.

Timeline

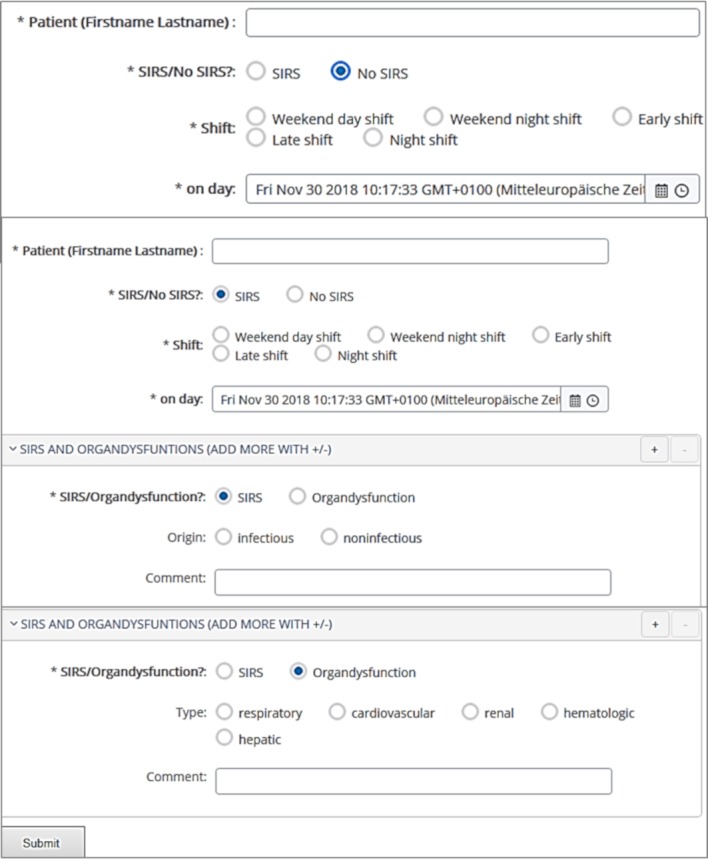

Before study start, the clinicians were introduced in their tasks. No interventions, treatments or other care-related actions are prohibited and patients are treated with standard procedures (including data collection and measurements). Personal briefings on the routine documentation were carried out during this pilot phase (1 July 2018, duration: 1 month, see figure 1). A designated physician will present the study to the patients, their parents or their legal guardians and ask for consent within the recruiting phase (1 August 2018, estimated duration: 10 months). Simultaneously, clinicians reported their findings during their working shift per patient (routine assessments, diagnostic approach II). The clinicians do not perform extensive analyses of documentations or reported data (assessment phase I, 1 August 2018, estimated duration: 10 months). In the routine assessments, it is documented whether the patient suffered from SIRS, sepsis or organ dysfunction (via digital documentation form, see figure 2). The first 2 weeks of this phase will be treated as test phase.

Figure 2.

Digital documentation form (based on open EHR data repository).

Later on, two experienced clinicians started with their weekly, extensive, blinded review and the definition of gold standard assessments per patient and per hour (assessment phase II, 1 May 2019, estimated duration: 2 months). As soon as 97 patients suffering from one or more SIRS episodes as well as 137 patients with one or without SIRS episodes have been identified, the recruitment will be terminated. Simultaneously, the data sets from all recruited patients will be integrated into a data repository to make them accessible for the CDSS. The CDSS assessments per patients and per hour will start (diagnostic approach I). In the final analysis phase (1 July 2019, estimated duration: 2 months), the diagnostic accuracy of the CDSS will be evaluated by comparing the assessments to the gold standard decisions from the experts (primary goal of the study). Additionally, the diagnostic accuracy of the routine assessments will be determined by comparing them to the same gold standard decisions. The different accuracies can be compared (secondary goal of the study). Finally, the study results will be communicated via publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Recruitment and consent

Eligible patients, their parents or their legal guardians will receive an information letter and a consent form (available in German, English, Turkish and Arabic) during a personal discussion with a physician. Additional information sheets for younger patients are available, one for children aged six to eleven and one for children aged 12 to 18. The families will receive privacy statement forms (data protection, accessibility and confidentiality; see online supplementary file 2).

bmjopen-2019-028953supp002.pdf (46.5KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

There were no funds or time allocated for patient and public involvement so we were unable to involve patients. We intend to disseminate the results to the participants and will invite patients to help us developing an appropriate method of dissemination.

Data management and collection

The CDSS is an application with interfaces to a data repository, which is based on an semantic interoperability standard for clinical information representation (openEHR28). For more information, we refer to Wulff et al.17 For the routine assessment (assessment phase I, diagnostic approach II), we created a documentation form, which is based on the same interoperability standard and the same interfaces to the data repository (see figure 2). Thereby, all results (gold standard, diagnostic approach I ‘CDSS’, diagnostic approach II ‘routine assessments’) will be available in the same format. Patient data (identification, birthdate), intensive care parameters (heart rate, respiratory rate, body temperature, leukocytes, neutrophils, mechanical ventilation, cooling devices, pacemaker), alert parameters (SIRS, sepsis, organ dysfunction with duration, beginning and end of the episode and shift), and general documentations of the patient conditions, events or unintended effects will be documented and processed.

Data monitoring and auditing

Quality assurance measures are continuously carried out. Plausibility checks will be executed while integrating data into our repository (eg, simple counts to uncover whether data from the primary source is missing in the repository). Furthermore, the data set will be reviewed by physicians with respect to randomly selected observations to guarantee the plausibility from a clinical perspective. By following the openEHR standard, we are able to automatically execute validation checks to uncover missing or wrong values when integrating the data sets or filling out the documentation form (eg, definition of ranges for specific values, or double data entries). The study procedures will be monitored by the authors as well as by designated physicians and nurses. They will supervise the adherence to the study protocol, the procedures for routine documentation and data integration, data quality and privacy.

Data protection: data access and confidentiality

We designed a data protection concept in cooperation with the local data security officer. The concept defines pseudonymisation and data access procedures, outlines the patient consent, and explains technical security mechanisms. All data sets collected or created as part of this study are treated as strictly confidential. The data sets will be stored pseudonymised and in secure conditions in the data repository located in the network of the Hannover Medical School. To prevent unauthorised disclosure of patient information, it is only accessible for the physicians and employees in charge of this study. Collected data from patients withdrawing their consent (drop outs), will be completely deleted from the data repository. All study files, the final study data sets as well as the study results will be archived for ten years in an approved long-term repository and in accordance to the relevant legal and statutory requirements. The patient will be informed about these procedures as well as their rights (including the possibility to withdraw the consent and to obtain information about collected data sets at any time), and will be asked to consent to these.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was given. The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03661450). Protocol modifications will require a formal amendment to the protocol which will be reported to the Hannover Medical School Ethics Committee for approval. All aspects are designed according to the General Data Protection Regulation from the European Union (2016/679) and are accepted by the data security officer of the Hannover Medical School. Further details on data protection aspects can be requested from the authors. Consent to participate will be given by the patients, by their parents or by their legal guardians by signing a study consent form. Results of the main study will be communicated via publication in a peer-reviewed journal. We intend to disseminate the results to the participants through an appropriate method of dissemination to be defined.

Discussion

To be used in the long run, CDSSs have to deliver relevant information in a timely manner and at an adequate frequency. Current approaches for evaluating the usefulness of CDSS indeed present positive results. However, due to a restricted study design not designed towards daily work conditions, results may not represent the system feasibility in routine clinical care. With our work, we contribute a modified study design for evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of a CDSS with a strong focus on routine clinical care. We hypothesise that such an evaluation will demonstrate the potentials of CDSS use in routine clinical care. In case of a positive study outcome, we will be able to reason that our CDSS is not only feasible from a technical but also from a clinical perspective as it supports clinicians in critical diagnostic decision-making. For evaluation, a so-called gold standard representing the true state of the patient is required. However, in complex, knowledge-and experience-based contexts as diagnostic decision-making, reproducible, objective and quantitative ‘gold standards’ are rare. We use an excessive evaluation of the patient data by two experience clinicians as benchmark. To reduce possible biases, the clinicians are blinded to each other and to the CDSS. In situations of disagreement, a third clinician will be consulted, decisions will be revealed and a consensus decision will be reported. We are aware that our approach is time-consuming requiring highly engaged clinicians. Because of the stressful PICU environment, assessments may be delayed, and thus, the study timeline may not be adhered. For an early recognition of issues and study monitoring at the ward, an assistant physician is in charge. Also the routine assessments of clinicians have to be managed as they are at the same risk to be biased. Clinical documentation might be handled more meticulous at the beginning and more careless in the end of the study. To prevent the latter, the new documentation form was designed in cooperation with the users and integrated in the PDMS used daily. Together with the designated study monitor, this integration raised the satisfactory and the utilisation rate of the form as well as the adherence to the study protocol.

For sample size calculation, it might be possible that the incidence was overestimated, so that in our settings more than 300 patients are needed to reach 97 patients suffering from at least one SIRS episode. The recruitment will be continuously aligned towards the number of recruited SIRS patients to be able to stop the recruitment as soon as the required number has been reached. Our expected values for sensitivity and specificity are rather conservative because we decided to primarily use an equally conservative statistical analysis approach. However, the expected values are treated as acceptable in clinical routine as the diagnostic accuracy of the system will be over a critical minimum (and with respect to the aspired second goal of our study, even better than in clinical routine decision-making). At the same time, alert fatigue will be prevented because specificity is equally high. We are confident that our thoughts meet the need for an optimum balance between sensitivity and specificity, for example, as reported by Coleman et al.23 Nevertheless, we will enhance our results with a more liberal analysis on the level of days.

Our study has been successfully started with recruitment according to this design and promises valuable results. When reaching a good diagnostic accuracy compared with the gold standard as well as advantages over the diagnostic accuracy of routine assessments, we are optimistic that our users are willing to trust and use the system in future. Moreover, this will allow the conduction of future studies as for example the evaluation of patient outcomes, user acceptability, or real-time performance of the system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We want to thank our colleagues from the ZIMt department for Educational and Scientific IT Systems of the Hannover Medical School for supporting in matters of data access and integration.

Footnotes

Contributors: AW was responsible for design and implementation of the presented clinical decision-support system and the outline of the study protocol, and has drafted the manuscript. TJ provided clinical expertise for the use case and the design of the underlying knowledge model, leaded the proof-of-concept study and co-drafted the manuscript. AK was primarily responsible for the design of the statistical analysis, the sample size calculation and the authoring of the corresponding sections. BS and SM helped in the conception of the general study approach but especially for definition of goals and outcome measures, timing and patient recruitment; SM is responsible for patient recruitment and monitors the study at the ward. PB and MM provided clinical expertise for study design, revised the manuscript critically, and gave subject-specific advices as well as the final approval of the manuscript version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was given by the Ethics Committee of Hannover Medical School (approval number 7804_BO_S_2018).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med 1992;20:864–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005;6:2–8. 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149131.72248.E6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wolfler A, Silvani P, Musicco M, et al. Incidence of and mortality due to sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock in Italian Pediatric Intensive Care Units: a prospective national survey. Intensive Care Med 2008;34:1690–7. 10.1007/s00134-008-1148-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cvetkovic M, Lutman D, Ramnarayan P, et al. Timing of death in children referred for intensive care with severe sepsis: implications for interventional studies. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2015;16:410–7. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Creedon JK, Vargas S, Asaro LA, et al. Timing of antibiotic administration in pediatric sepsis. Pediatr Emerg Care 2018:1 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kortz TB, Sawe HR, Murray B, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes among children with sepsis presenting to a public tertiary hospital in Tanzania. Front Pediatr 2017;5:278 10.3389/fped.2017.00278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boehne M, Sasse M, Karch A, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome after pediatric congenital heart surgery: Incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcome. J Card Surg 2017;32:116–25. 10.1111/jocs.12879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ganjoo S, Ahmad K, Qureshi UA, et al. Clinical epidemiology of SIRS and sepsis in newly admitted children. Indian J Pediatr 2015;82:698–702. 10.1007/s12098-014-1618-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Han YY, Carcillo JA, Dragotta MA, et al. Early reversal of pediatric-neonatal septic shock by community physicians is associated with improved outcome. Pediatrics 2003;112:793–9. 10.1542/peds.112.4.793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Paul R. Recognition, diagnostics, and management of pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock in the emergency department. Pediatr Clin North Am 2018;65:1107–18. 10.1016/j.pcl.2018.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sackett DL. Evidence-based medicine. Semin Perinatol 1997;21:3–5. 10.1016/S0146-0005(97)80013-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zavala AM, Day GE, Plummer D, et al. Decision-making under pressure: medical errors in uncertain and dynamic environments. Aust Health Rev 2018;42:395-402 10.1071/AH16088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lighthall GK, Vazquez-Guillamet C. Understanding decision making in critical care. Clin Med Res 2015;13:156–68. 10.3121/cmr.2015.1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Castaneda C, Nalley K, Mannion C, et al. Clinical decision support systems for improving diagnostic accuracy and achieving precision medicine. J Clin Bioinforma 2015;5:4 10.1186/s13336-015-0019-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lincoln P, Manning MJ, Hamilton S, et al. A pediatric critical care practice group: use of expertise and evidence-based practice in identifying and establishing "best" practice. Crit Care Nurse 2013;33:85–7. 10.4037/ccn2013740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shortliffe EH. Biomedical informatics: defining the science and its role in health professional education : Hutchison D, Kanade T, Kittler J, Information quality in e-health. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2011:711–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wulff A, Haarbrandt B, Tute E, et al. An interoperable clinical decision-support system for early detection of SIRS in pediatric intensive care using openEHR. Artif Intell Med 2018;89:10–23. 10.1016/j.artmed.2018.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wulff A, Marschollek M. Learning healthcare systems in pediatrics: Cross-Institutional and Data-Driven Decision-Support for Intensive Care Environments (CADDIE). Stud Health Technol Inform 2018;251:109–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Faisal M, Scally A, Richardson D, et al. Development and external validation of an automated computer-aided risk score for predicting sepsis in emergency medical admissions using the patient’s first electronically recorded vital signs and blood test results. Crit Care Med 2018;46:612–8. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Austrian JS, Jamin CT, Doty GR, et al. Impact of an emergency department electronic sepsis surveillance system on patient mortality and length of stay. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018;25:523–9. 10.1093/jamia/ocx072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mao Q, Jay M, Hoffman JL, et al. Multicentre validation of a sepsis prediction algorithm using only vital sign data in the emergency department, general ward and ICU. BMJ Open 2018;8:e017833 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kilsdonk E, Peute LW, Jaspers MW. Factors influencing implementation success of guideline-based clinical decision support systems: A systematic review and gaps analysis. Int J Med Inform 2017;98:56–64. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Coleman JJ, van der Sijs H, Haefeli WE, et al. On the alert: future priorities for alerts in clinical decision support for computerized physician order entry identified from a European workshop. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13:111 10.1186/1472-6947-13-111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liberati EG, Ruggiero F, Galuppo L, et al. What hinders the uptake of computerized decision support systems in hospitals? A qualitative study and framework for implementation. Implement Sci 2017;12:113 10.1186/s13012-017-0644-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jack T, Boehne M, Brent BE, et al. In-line filtration reduces severe complications and length of stay on pediatric intensive care unit: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:1008–16. 10.1007/s00134-012-2539-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cohen JF, Korevaar DA, Altman DG, et al. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012799 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beale T. Archetypes: constraint-based domain models for future-proof information systems : Eleventh OOPSLA workshop on behavioral semantics: serving the customer. Seattle, Washington, Boston: Northeastern University, 2002:16–32. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-028953supp001.pdf (44.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-028953supp002.pdf (46.5KB, pdf)