Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to evaluate the effect of the implementation of a fast-track on emergency department (ED) length of stay (LOS) and quality of care indicators.

Design

Adjusted before–after analysis.

Setting

A large hospital in the Champagne-Ardenne region, France.

Participants

Patients admitted to the ED between 13 January 2015 and 13 January 2017.

Intervention

Implementation of a fast-track for patients with small injuries or benign medical conditions (13 January 2016).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Proportion of patients with LOS ≥4 hours and proportion of access block situations (when patients cannot access an appropriate hospital bed within 8 hours). 7-day readmissions and 30-day readmissions.

Results

The ED of the intervention hospital registered 53 768 stays in 2016 and 57 965 in 2017 (+7.8%). In the intervention hospital, the median LOS was 215 min before the intervention and 186 min after the intervention. The exponentiated before–after estimator for ED LOS ≥4 hours was 0.79; 95% CI 0.77 to 0.81. The exponentiated before–after estimator for access block was 1.19; 95% CI 1.13 to 1.25. There was an increase in the proportion of 30 day readmissions in the intervention hospital (from 11.4% to 12.3%). After the intervention, the proportion of patients leaving without being seen by a physician decreased from 10.0% to 5.4%.

Conclusions

The implementation of a fast-track was associated with a decrease in stays lasting ≥4 hours without a decrease in access block. Further studies are needed to evaluate the causes of variability in ED LOS and their connections to quality of care indicators.

Keywords: emergency department, length of stay, fast-track, hospital readmissions, healthcare quality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We measured the effect of the implementation of a fast-track on length of stay and quality of care indicators.

We controlled for potential confounders (primary diagnosis, severity…) with a multivariable analysis by logistic regression. The uncertainty induced by missing values was accounted for by pooling estimates from multiple imputations.

The intervention was the only major change in the hospital under study.

Further studies could include more hospitals.

Introduction

The number of annual emergency department (ED) visits has doubled between 1980 and 2004 in France,1 and is still rising (+3.7% between 2014 and 2015). This phenomenon has been observed in most developed countries,2 and is a challenge for physicians and policy-makers. ED crowding was defined by the American College of Emergency Physicians as a mismatch between the need for emergency care and the ED’s ability to provide this care.3 ED crowding has been associated with longer ED length of stay (LOS),4 inadequate pain management,5 and worse patient outcomes.6 A crowded ED may sometimes need to fall back on ambulance diversion, redirecting patients to nearby hospitals. Finding the best organisation for EDs is therefore a public health priority with ethical implications.3 The causes of ED crowding include increased demand from patients, epidemics, lack of trained staff and lack of hospital beds.7 Numerous scores have been proposed to measure ED crowding (EDWIN, NEDOCS, READI, Work Score) however their predictive power typically does not outperform simpler indicators such as bed occupancy.8 9 Time series analysis can predict ED activity with a Relative Mean Absolute Performance of 90%.10 A shorter LOS results in less complications,11 12 higher odds of survival for severe patients,13 increased patient satisfaction14 15 and lower healthcare spending.16 The optimisation of patient flow has been studied extensively.17 18 Numerous strategies have been proposed to regulate patient flow in the ED: care coordination teams, whose mission involves orienting older patients towards appropriate healthcare, observation units (caring for patients up to 72 hours), chest pain units, home-based healthcare.19 A common strategy is the use of fast-tracks, dedicated pathways aimed towards the fast delivery of healthcare for patients with benign medical conditions scheduled for rapid discharge. Fast-tracks have been implemented in small and larger hospitals.20 In 2002, 58% of 17 surveyed Australian public hospitals functioned with a fast-track.19 A Monte-Carlo simulation showed that implementing a fast-track with a dedicated nurse could shorten median waiting times up to 35%.21 Previous studies have evaluated the effect of implementing a fast-track,22–25 however the length of these studies was short, typically less than 6 months. One 2-year study with a fast-track staffed with mid-level providers did not adjust for patient severity.26 The aim of this study was to assess the impact of an ED restructuring with the implementation of a fast-track on ED LOS in the setting of a large hospital in France. Secondary objectives were to study predictors of ED LOS, and to assess the effect of the ED restructuration on 7-day readmissions, 30-day readmissions and the proportion of patients leaving without being seen.

Methods

We conducted a before–after analysis with adjustment on confounders.

Population

The region in which the study took place is one of the least densely populated regions in France. The age structure of the region resembles the pooled age structure of the rest of the country. The intervention hospital (Troyes Hospital) was a large hospital with 442 medical beds, 127 surgical beds and 63 beds dedicated to gynaecology and obstetrics, serving an area of approximately 40 kilometres radius (25 miles). The ED hosted an observation unit.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design or analysis of this study.

Intervention

The intervention included an extension of the ED from 15 to 27 consultation rooms and the opening of a fast-track for patients with small injuries or benign medical conditions. The fast-track in the intervention hospital had six rooms. The fast-track is a healthcare pathway for the assessment and treatment of low-severity patients, situated in a dedicated area of the ED. The intervention was implemented on 13 January 2016. Two ED physicians managed adult patients and paediatric traumatology in the fast-track. When ED physicians were not available, they were replaced by residents. Gynaecology and psychiatry patients could also be managed in dedicated areas of the fast-track. Entry criteria for the fast-track were predefined in a protocol (see online supplementary appendix 1).

bmjopen-2018-026200supp001.pdf (104.8KB, pdf)

Outcomes

The main outcome was an ED LOS ≥4 hours.27 28 LOS was defined as the time elapsed between registration in the ED to the time the patient leaves the ED. The secondary outcome was access block, defined by the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine as the situation where patients who need hospital care cannot access an appropriate hospital bed within a reasonable delay (8 hours).29 We used the Patient State (PS) classification10 presented in table 1 to identify patients that needed to be admitted to the hospital (PS 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7). Time to physician appraisal and LOS were extracted from local hospital databases (data extracted from Resurgences© in the intervention hospital). Other quality of care indicators included the number of patients leaving without being seen30 and the monthly proportion of 30-day and 7-day readmissions.31

Table 1.

Patient State (PS) classification for patients admitted to the emergency department

| PS class | Description |

| PS1 | Patient with moderate treatment, discharged from emergency department. |

| PS2 | Patient with major treatment, discharged from emergency department. |

| PS3 | Patient with moderate treatment, hospitalised after emergency department stay. |

| PS4 | Patient with major treatment, hospitalised after emergency department stay. |

| PS5 | Patients requiring immediate treatment, not elsewhere classified. |

| PS6 | Patients requiring immediate intensive care/resuscitation. |

| PS7 | Died in emergency department. |

Statistical methods

Continuous variables were summarised with means and SD or medians and the IQR. Categorical variables were presented with absolute frequencies and proportions. A descriptive analysis was carried out for LOS by period. Differences between the period before the intervention and the period after the intervention were compared with Student’s t-test or with the Mann-Whitney U test for asymmetrically distributed variables, and with the χ2 test for categorical variables. Summary statistics were provided for the waiting times of patients with selected diagnoses (pneumonia, stroke, myocardial infarction and heart failure). To facilitate modelling, LOS was transformed into a binary variable using thresholds classically found in the literature.28 Separate models were fitted to study the primary outcome and access block. The effect of the intervention on the primary outcome was evaluated for all patients. The effect of the intervention on access block was evaluated in an analysis restricted to patients who needed to be hospitalised after their ED stay. Multivariable logistic regression models were estimated to adjust for confounders. The model was Logit(p)=α + πP+T’τ +X’β, with p being the probability of the outcome, α the intercept, P an indicator variable for period, T a vector of additional time variables (effect of being admitted during the night, the weekend or winter months) and X a vector of individual-level covariates. Age was grouped in categories relevant to clinical practice. Primary diagnosis was defined using chapters of the International Classification of Disease 10th revision (ICD-10) to avoid problems in estimation due to sparse data. Patient severity was included in the model using the PS classification.10 Time variables included indicator variables for admission during the night (22:00–06:00 hours), and during weekends (Saturday and Sunday). An indicator variable for December and January, where influenza epidemics often occur, was included in the model. The study sample was a convenience sample with a time window constructed symmetrically around the intervention, allowing to control for seasonal effects. Missing data were treated by multiple imputation with m=20 imputations. The proportion of patients leaving without being seen was a secondary outcome. Due to the paucity of information on these patients, it was not included as an dependent variable for multivariable analysis. Statistical analysis, data management and figures were realised using R V.3.5.3 (www.r-project.org).32

Results

Between 13 January 2015 and 13 January 2017, 111733 ED stays were registered in the intervention hospital (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

There were 53 768 stays in 2016 and 57 965 stays in 2017 (+7.8%). Regarding human resources, physicians increased from 11.5 to 14.5 full-time equivalents (FTE), nurses from 35.3 to 36.8 FTE, and assistant nurses from 16.8 to 19.5 FTE. The median LOS was 215 min (IQR Q1–Q3: 111–361) before the intervention and 186 min (98–340) after the intervention (table 2). The proportion of patients with LOS <4 hours changed from 55.2% to 60.6%. Within the subgroups of patients subsequently admitted to the hospital, patients consulting for pneumonia had a decrease in median time to physician assessment after the intervention: from 87 min (41–173) to 79 min (36–165). Stroke patients also had decreased median waiting times: from 77 (34–155) to 62 (33–132) minutes. The time to physician assessment remained unchanged for patients consulting for myocardial infarction and heart failure: from 61 (31–149) before the intervention to 63 (30–150) minutes after the intervention.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of study population, length of stay and readmissions in the intervention hospital

| Intervention | P value | ||

| 2015–2016* | 2016–2017† | ||

| Mean (SD), median (Q1–Q3) or n (%) | Mean (SD), median (Q1–Q3) or n (%) | ||

| n | 53 768 | 57 965 | – |

| Age (years): mean (SD) | 40.4 (27.3) | 39.8 (27.4) | <0.001‡ |

| Sex: female–n (%) | 26 712 (49.7) | 29 235 (50.4) | 0.01§ |

| Length of stay (min): median (Q1– Q3) | 215 (111–361) | 186 (98–340) | <0.001‡ |

| 7-day readmissions: n (%) | 3177 (5.9) | 3642 (6.3) | 0.01§ |

| 30-day readmissions: n (%) | 6105 (11.4) | 7129 (12.3) | <0.001§ |

| Patients admitted to hospital after emergency department: n | 14 795 | 14 864 | – |

| Length of stay (min): median (Q1–Q3) | 316 (181–465) | 333 (187–490) | <0.001‡ |

| Patients not admitted to hospital after emergency department | |||

| n | 38 971 | 43 100 | – |

| Length of stay (min): median (Q1–Q3) | 185 (97–310) | 155 (86–272) | <0.001‡ |

Q1–Q3: IQR

*13/01/2015 to morning of 13/01/2016.

†13/01/2016 afternoon to 13/01/2017.

‡Mann-Whitney U test.

§χ2 test.

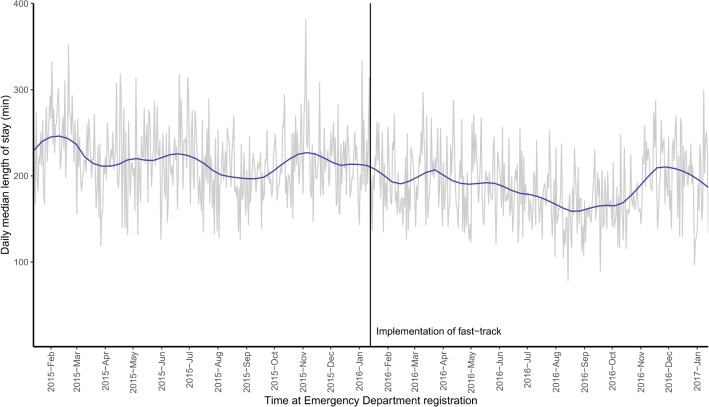

The exponentiated before–after estimator was 0.788 (95% CI 0.767 to 0.810, p<0.0001), therefore the intervention successfully reduced the number of ED stays with LOS ≥4 hours (table 3). However, the estimate for access block was 1.188 (95% CI 1.126 to 1.253, p<0.001): the intervention did not seem effective in helping the patients who needed it to access an appropriate hospital bed in a reasonable amount of time (<8 hours). In 4.8% of cases, none of the scores that constituted the PS classification were present. These cases were essentially patients who left the ED without being seen. Age was linearly related with LOS, with younger patients having a shorter LOS. Weekends were associated with a shorter LOS. Patients admitted for injuries (ICD-10 codes S00 to T98) and skin problems (L00 to L99) tended to have a short LOS, while patients admitted for neurological diseases (G00–G99) tended to have a longer LOS. Trends in daily median LOS are shown in figure 2.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression for length of stay ≥4 hours and access block

| Variable | OR (emergency department length of stay ≥4 hours for all patients)* | 95% CI | ORs (access block: emergency department length of stay ≥8 hours for hospitalised patients)* | 95% CI |

| Period: after intervention (reference=before intervention) | 0.788 | 0.767 to 0.810 | 1.188 | 1.126 to 1.253 |

| 7-day readmission | 0.833 | 0.786 to 0.882 | 0.867 | 0.773 to 0.973 |

| 8–30 days readmission | 0.974 | 0.918 to 1.033 | 0.938 | 0.849 to 1.037 |

| Weekend day | 0.936 | 0.908 to 0.966 | 0.761 | 0.714 to 0.811 |

| Night | 0.594 | 0.572 to 0.618 | 0.878 | 0.811 to 0.950 |

| Principal diagnosis (ICD-10 Chapter) | ||||

| Injury, poisoning | 0.559 | 0.508 to 0.616 | 0.641 | 0.568 to 0.723 |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 2.113 | 1.846 to 2.419 | 1.269 | 1.065 to 1.511 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | 0.466 | 0.404 to 0.537 | 0.573 | 0.413 to 0.795 |

| Neoplasms | 1.175 | 0.843 to 1.637 | 2.098 | 1.486 to 2.963 |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 1 (Reference) | – | 1 (Reference) | – |

| Month: December and January (reference=other months) | 1.159 | 1.118 to 1.202 | 1.49 | 1.390 to 1.597 |

| Severity (PS classification) | ||||

| PS1 | 1 (Reference) | – | – | – |

| PS2 | 1.890 | 1.668 to 2.142 | – | – |

| PS3 | 2.234 | 2.157 to 2.313 | 1 (Reference) | – |

| PS4 | 1.669 | 1.560 to 1.785 | 0.804 | 0.747 to 0.865 |

| PS5 | 0.470 | 0.395 to 0.560 | 0.397 | 0.316 to 0.499 |

| PS6 | 0.336 | 0.268 to 0.420 | 0.246 | 0.176 to 0.344 |

| PS7 | 0.315 | 0.201 to 0.492 | 0.333 | 0.175 to 0.637 |

| Sex: female (reference=male) | 0.994 | 0.966 to 1.022 | 1.072 | 1.014 to 1.134 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 50–64 | 1.611 | 1.547 to 1.679 | 1.387 | 1.271 to 1.514 |

| 65–74 | 2.152 | 2.041 to 2.269 | 1.681 | 1.532 to 1.846 |

| 75–89 | 3.367 | 3.210 to 3.532 | 2.025 | 1.873 to 2.189 |

| ≥90 | 4.330 | 3.970 to 4.721 | 2.117 | 1.906 to 2.352 |

| 0–17 | 0.292 | 0.280 to 0.304 | 0.099 | 0.082 to 0.120 |

| 18–50 | 1 (Reference) | – | 1 (Reference) | – |

ICD-10: International Classification of Disease, 10th revision.

*Multivariable analysis adjusted for age, sex, time of the day (night-time or daytime), time in the week (weekend day or weekday), time of the year (December and January or other months, admission diagnosis (grouped using ICD-10 chapters) and severity (using the PS classification).

ICD-10, International Classification of Disease 10th revision; PS, Patient State.

Figure 2.

Daily median emergency department length of stay during the study period (trends obtained by locally weighted regression).

Effect on quality of care indicators

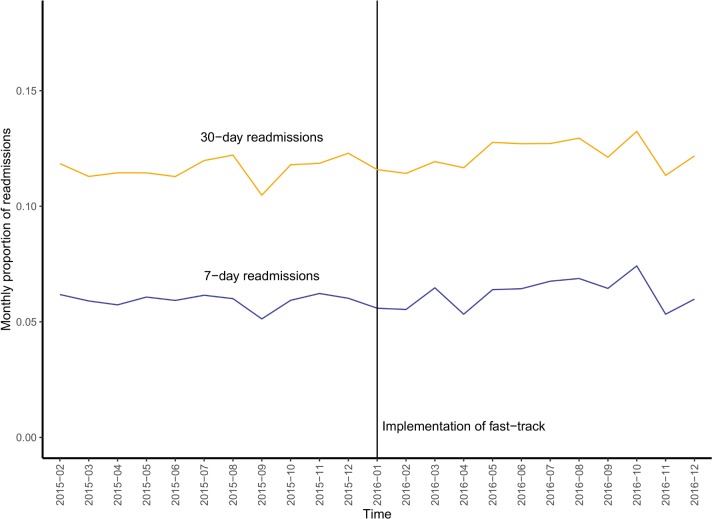

Overall, 12.0% of stays were 30-day readmissions. Most readmissions (6.1%) occurred within the first 7 days. There was a trend for increasing 30-day readmissions during the study period (figure 3). Seven-day readmissions increased from 5.9% to 6.3% in the intervention group. After the intervention, the proportion of patients leaving without being seen by a physician decreased from 10.0% to 5.4%.

Figure 3.

Proportion of emergency department 7-day and 30-day readmissions during the study period.

Discussion

Our study showed that implementing a fast-track can decrease the median LOS and number of stays lasting ≥4 hours in the ED of a large general hospital. We did not observe a decrease in LOS for patients requiring hospitalisation. However, the LOS for severe patients may have been limited by hospital-level bed availability rather than ED-related factors.33 Indeed, other studies have found that the implementation of a fast-track did not adversely affect LOS for patients subsequently admitted to the hospital.34

The addition of new beds to the ED could explain part of our results. However, the addition of new beds does not guarantee improved access to care. In a study by Han et al, the time between ambulance diversion episodes was not significantly different after expanding an ED from 28 to 53 beds.35

Asplin et al consider the ED as a system with three components: input, throughput and output.36 The input component includes events, diseases or other factors that contribute to the demand for urgent care. Throughput includes triage, room placement, diagnosis and treatment. The implementation of the fast-track can accelerate throughput for patients not subsequently admitted to the hospital. The decrease in LOS can be explained by decreased crowding due to rapid patient discharge, floorplan modifications allowing faster patient transfers, or physician and nurse role adjustments.37 38 Fast-tracks can efficiently coexist with other patient streams, such as tracks dedicated to complex ambulant patients.39 Regarding output, the limiting factor for ED LOS is often lack of available hospital beds. Some authors have suggested that an occupancy of 85% is a suitable target to ensure that new patients are not left without beds.40 This seems difficult to implement under current conditions. A systematic review of 220 articles discussing strategies to prevent ‘access block’29 mentions interventions to diminish the number of patients admitted to the ED and observation wards.41 Other solutions to prevent ED crowding are: sharing optimal care processes,42 enrolling additional staff8 or eventually redirecting patients towards other centres.7 Causes of increased demand for urgent care include the ageing of populations, with a higher prevalence of chronic diseases, the scarcity of primary care and changing perceptions of what is considered urgent. Solitude is a major driver of ED consultations.43 The efficacy of gatekeeping procedures has yet to be evaluated.44 The patients that frequently consult in the ED, however, are often disadvantaged by a low socio-economic status45 and can be considered a high-risk group regarding morbidity and mortality.46 Prior contact with the ED could help improve communication with the patient, although an effect on the number of ED admissions remains to be established.47 Pain is a major complaint in the ED, and patients with chronic pain could be more likely to consult.48 Access to programmed care is crucial, and patients who cannot access programmed care will come back to the ED. In an Australian study, around half of patients would prefer to see a general practitioner for a similar problem than to be treated in the emergency fast-track.49 In this regard, what is happening in EDs can be seen as a mirror of the dysfunctions in a healthcare system.50

After the implementation of the fast-track, the number of patients registered in the ED increased by 7.8%. This is unlikely to be a fluctuation in epidemiological trends, but rather reflects an increased demand generated by an easier access to timely care. Patients leaving without being seen diminished from 10.0% to 5.4%, similar to the proportions in studies by Combs et al 51 and Sanchez et al.26

Among other quality of care indicators, we evaluated ED 7-day and 30-day readmissions.52 The main rationale for including these indicators was to appreciate the extent by which the decrease in LOS was explained by readmissions of the same patients. Seven-day readmissions increased after the implementation of the fast-track. Patients coming back to the hospital within 7 days had shorter lengths of stay during the readmission. One possible explanation is the availability of the patient’s recent history, making medical assessment simpler. EDs may have a role to play in preventing hospital readmissions.53 However, recent studies show that hospital readmissions are often not avoidable, and are largely influenced by factors on which hospitals have no control, like socioeconomic status.31 54 As is often the case, these indicators need to be appraised in conjunction with other quality of care indicators.

The intervention was the only major change in the ED during this period. The major limitation of our study was that the effect of implementing a fast-track was confounded with the addition of staff and new beds to the ED to allow it to function effectively under increased constraints. However, the reported increase in FTEs was due to the administrative transfer of staff from the mobile unit for emergencies and intensive care. Only one additional nurse was fully allocated to the ED. As the mobile unit’s main activity is to intervene outside of the hospital, it is unlikely that the observed changes in LOS were entirely explained by the increase in human resources. Moreover, because supplemental beds were added to the ED as part of the intervention, the ratio of staff to beds decreased. A multiple imputation was carried out to account for the uncertainty induced by missing PS severity scores, with m=20 imputations. Patients who left without being seen were kept in the imputation model. As these patients were more frequent in the period before the intervention, and their LOS was shorter than the rest of the population (median 156 min), the efficacy of the intervention regarding LOS could be underestimated. To conclude, our study showed an increase in short stays for low acuity patients following the implementation of the fast-track. In this regard, the fast-track consolidated the ED’s role of compensating deficiencies in access to primary care, without favourably impacting LOS for severe patients. Hospital-level bed availability is critical to ensure efficient healthcare for patients registered to the ED. Studies including more hospitals and a larger array of quality of care indicators are warranted to estimate the effect of implementing a fast-track on ED performance and population health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mohamed Afilal and Priscilla De Souza for their contributions in data extraction.

Footnotes

Contributors: JC, DL, AD, LK and SS designed the study. SS, DL, XF, AC contributed to the acquisition of data. JC conducted the statistical analysis. JC, XF, AD, AC, DL, LK and SS contributed to drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: All legal requirements for epidemiological studies were respected, and the French national commission governing the application of data privacy laws issued an approval for the project.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: To prevent dissemination of sensitive patient data, the dataset on which this study was based was not made available to the public.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. France. Cour des comptes. Les urgences médicales : constats et évolution récente Rapport public annuel 2007. Paris: La Documentation Française, 2007:312. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pines JM, Hilton JA, Weber EJ, et al. International perspectives on emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:1358–70. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moskop JC, Sklar DP, Geiderman JM, et al. Emergency department crowding, part 1–concept, causes, and moral consequences. Ann Emerg Med 2009;53:605–11. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chiu IM, Lin YR, Syue YJ, et al. The influence of crowding on clinical practice in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2018;36:56–60. 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hwang U, Richardson LD, Sonuyi TO, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on the management of pain in older adults with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:270–5. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00587.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sprivulis PC, Da Silva JA, Jacobs IG, et al. The association between hospital overcrowding and mortality among patients admitted via Western Australian emergency departments. Med J Aust 2006;184:208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med 2008;52:126–36. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoot NR, Zhou C, Jones I, et al. Measuring and forecasting emergency department crowding in real time. Ann Emerg Med 2007;49:747–55. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoot N, Aronsky D. An early warning system for overcrowding in the emergency department. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2006;2006:339–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Afilal M, Yalaoui F, Dugardin F, et al. Forecasting the Emergency Department Patients Flow. J Med Syst 2016;40:175 10.1007/s10916-016-0527-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carr BG, Kaye AJ, Wiebe DJ, et al. Emergency department length of stay: a major risk factor for pneumonia in intubated blunt trauma patients. J Trauma 2007;63:9–12. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31805d8f6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Diercks DB, Roe MT, Chen AY, et al. Prolonged emergency department stays of non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients are associated with worse adherence to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for management and increased adverse events. Ann Emerg Med 2007;50:489–96. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chalfin DB, Trzeciak S, Likourezos A, et al. Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2007;35:1477–83. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266585.74905.5A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:1–10. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00295.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guttmann A, Schull MJ, Vermeulen MJ, et al. Association between waiting times and short term mortality and hospital admission after departure from emergency department: population based cohort study from Ontario, Canada. BMJ 2011;342:d2983 10.1136/bmj.d2983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bayley MD, Schwartz JS, Shofer FS, et al. The financial burden of emergency department congestion and hospital crowding for chest pain patients awaiting admission. Ann Emerg Med 2005;45:110–7. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jarvis PR. Improving emergency department patient flow. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2016;3:63–8. 10.15441/ceem.16.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Le Spégnane D, Cauterman M. Rapport de fin de mission « Temps d’attente et de passage aux Urgences ». Juillet 2003 – mars 2005. Paris: Mission Nationale d’Expertise et d’Audit Hospitaliers, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19. McD Taylor D, Bennett DM, Cameron PA. A paradigm shift in the nature of care provision in emergency departments. Emerg Med J 2004;21:681–4. 10.1136/emj.2004.017640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kilic YA, Agalar FA, Kunt M, et al. Prospective, double-blind, comparative fast-tracking trial in an academic emergency department during a period of limited resources. Eur J Emerg Med Off J Eur Soc Emerg Med 1998;5:403–6. 10.1097/00063110-199812000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fitzgerald K, Pelletier L, Reznek MA. A Queue-Based Monte Carlo Analysis to Support Decision Making for Implementation of an Emergency Department Fast Track. J Healthc Eng 2017;2017:1–8. 10.1155/2017/6536523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cooke MW, Wilson S, Pearson S. The effect of a separate stream for minor injuries on accident and emergency department waiting times. Emerg Med J 2002;19:28–30. 10.1136/emj.19.1.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rogers T, Ross N, Spooner D. Evaluation of a ’See and Treat' pilot study introduced to an emergency department. Accid Emerg Nurs 2004;12:24–7. 10.1016/j.aaen.2003.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ardagh MW, Wells JE, Cooper K, et al. Effect of a rapid assessment clinic on the waiting time to be seen by a doctor and the time spent in the department, for patients presenting to an urban emergency department: a controlled prospective trial. N Z Med J 2002;115:U28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kwa P, Blake D. Fast track: has it changed patient care in the emergency department? Emerg Med Australas 2008;20:10–15. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.01021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sanchez M, Smally AJ, Grant RJ, et al. Effects of a fast-track area on emergency department performance. J Emerg Med 2006;31:117–20. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gill SD, Lane SE, Sheridan M, et al. Why do ’fast track' patients stay more than four hours in the emergency department? An investigation of factors that predict length of stay. Emerg Med Australas 2018;30:641–7. 10.1111/1742-6723.12964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, et al. New emergency department quality measure: from access block to National Emergency Access Target compliance. Emerg Med Australas 2013;25:565–72. 10.1111/1742-6723.12139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Forero R, McCarthy S, Hillman K. Access block and emergency department overcrowding. Crit Care 2011;15:216 10.1186/cc9998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Broccoli MC, Moresky R, Dixon J, et al. Defining quality indicators for emergency care delivery: findings of an expert consensus process by emergency care practitioners in Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000479 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Graham KL, Auerbach AD, Schnipper JL, et al. Preventability of Early Versus Late Hospital Readmissions in a National Cohort of General Medicine Patients. Ann Intern Med 2018;168:766–74. 10.7326/M17-1724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2016. https://www.R-project.org/

- 33. Powell ES, Khare RK, Venkatesh AK, et al. The relationship between inpatient discharge timing and emergency department boarding. J Emerg Med 2012;42:186–96. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Considine J, Kropman M, Kelly E, et al. Effect of emergency department fast track on emergency department length of stay: a case-control study. Emerg Med J 2008;25:815–9. 10.1136/emj.2008.057919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Han JH, Zhou C, France DJ, et al. The effect of emergency department expansion on emergency department overcrowding. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:338–43. 10.1197/j.aem.2006.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Asplin BR, Magid DJ, Rhodes KV, et al. A conceptual model of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med 2003;42:173–80. 10.1067/mem.2003.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Walley P. Designing the accident and emergency system: lessons from manufacturing. Emerg Med J 2003;20:126–30. 10.1136/emj.20.2.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kaushal A, Zhao Y, Peng Q, et al. Evaluation of fast track strategies using agent-based simulation modeling to reduce waiting time in a hospital emergency department. Socioecon Plann Sci 2015;50:18–31. 10.1016/j.seps.2015.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grouse AI, Bishop RO, Gerlach L, et al. A stream for complex, ambulant patients reduces crowding in an emergency department. Emerg Med Australas 2014;26:164–9. 10.1111/1742-6723.12204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cameron PA, Joseph AP, McCarthy SM. Access block can be managed. Med J Aust 2009;190:364–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kelen GD, Scheulen JJ, Hill PM. Effect of an emergency department (ED) managed acute care unit on ED overcrowding and emergency medical services diversion. Acad Emerg Med 2001;8:1095–100. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoffenberg S, Hill MB, Houry D. Does sharing process differences reduce patient length of stay in the emergency department? Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:533–40. 10.1067/mem.2001.119426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Geller J, Janson P, McGovern E, et al. Loneliness as a predictor of hospital emergency department use. J Fam Pract 1999;48:801–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. van Uden CJ, Winkens RA, Wesseling GJ, et al. Use of out of hours services: a comparison between two organisations. Emerg Med J 2003;20:184–7. 10.1136/emj.20.2.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lombrail P, Vitoux-Brot C, Bourrillon A, et al. Another look at emergency room overcrowding: accessibility of the health services and quality of care. Int J Qual Health Care J Int Soc Qual Health Care 1997;9:225–35. 10.1093/intqhc/9.3.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hansagi H, Edhag O, Allebeck P. High consumers of health care in emergency units: how to improve their quality of care. Qual Assur Health Care 1991;3:51–62. 10.1093/intqhc/3.1.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Graber DJ, Ardagh MW, O’Donovan P, et al. A telephone advice line does not decrease the number of presentations to Christchurch Emergency Department, but does decrease the number of phone callers seeking advice. N Z Med J 2003;116:U495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cordell WH, Keene KK, Giles BK, et al. The high prevalence of pain in emergency medical care. Am J Emerg Med 2002;20:165–9. 10.1053/ajem.2002.32643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lutze M, Ross M, Chu M, et al. Patient perceptions of emergency department fast track: a prospective pilot study comparing two models of care. Australas Emerg Nurs J 2014;17:112–8. 10.1016/j.aenj.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cohen L, Génisson C, Savary RP. Les urgences hospitalières: miroir des dysfonctionnements du système de santé. Paris: Sénat, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Combs S, Chapman R, Bushby A. Evaluation of Fast Track. Accid Emerg Nurs 2007;15:40–7. 10.1016/j.aaen.2006.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gupta A, Allen LA, Bhatt DL, et al. Association of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program Implementation With Readmission and Mortality Outcomes in Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:44–53. 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Singh S, Lin YL, Nattinger AB, et al. Variation in readmission rates by emergency departments and emergency department providers caring for patients after discharge. J Hosp Med 2015;10:705–10. 10.1002/jhm.2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McIlvennan CK, Eapen ZJ, Allen LA. Hospital readmissions reduction program. Circulation 2015;131:1796–803. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026200supp001.pdf (104.8KB, pdf)