Abstract

Objectives

To analyse the association between aminosalicylate-treated inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) at population level.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

The study was performed based on electronic drug prescription and dispensation records of the Andalusian Public Health System.

Participants

All individuals aged ≥50 years with at least one drug dispensation during December 2014 were identified from the records.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Groups were formed: ‘possible PD’ group, including all who received an anti-Parkinson agent; ‘possible IBD’ group, those treated with mesalazine and/or derivatives (5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA)); and ‘possible PD and IBD’, including those receiving both anti-Parkinson agent and 5-ASA. Prevalence of possible PD was determined among those with possible IBD and among those without this condition. The age-adjusted and sex-adjusted OR was calculated.

Results

We recorded 2 020 868 individuals (68±11 years, 56% female), 19 966 were included in possible PD group (75±9 years, 53% female) and 7485 in possible IBD group (64±10 years, 47% female); only 56 were included in both groups (76±8 years, 32% female). The prevalence of possible PD was 0.7% among those with possible IBD and 1% among those without this condition (adjusted OR=0.94; 95% CI 0.72 to 1.23; p=0.657). OR was 0.28 in individuals aged ≤65 years (95% CI 0.10 to 0.74; p=0.01) and 1.17 in older individuals (95% CI 0.89 to 1.54; p=0.257).

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, the results suggest a protective role for IBD and/or 5-ASA against PD development, especially among under 65-year olds. Further studies are warranted to explore this association given its scientific and therapeutic implications.

Keywords: 5-ASA, Parkinson’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, alpha-synuclein, microbiota, prevalence

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study that analyses the association between aminosalicylate-treated inflammatory bowel disease and Parkinson’s disease at population level.

We conducted this study with a large population-based sample.

The study was performed based on electronic drug prescription and dispensation records of the Andalusian Public Health System, Spain.

This study has limitations related to the utilisation of a drug dispensation record, and there is also a potential classification error related to the selection of proxy variables.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a multisystemic process with early involvement of the peripheral autonomic nervous system and subsequent propagation to the central nervous system.1 After reports of deposits of alpha-synuclein aggregates that form neurites or Lewy bodies in gastric submucosal and myenteric plexi,1 various clinical and experimental studies described the enteric nervous system as fundamental in the etiopathogenesis of PD.1–5 Braak’s ‘dual-hit’ hypothesis has been endorsed by evidence of the centripetal trans-synaptic and axonal migration of alpha-synuclein aggregates from neurons of the digestive system to brainstem structures such as the dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve (Braak stage 2).1–3 It has been reported that certain components of the microbiota of PD patients can produce rupture of the intestinal barrier and bacterial translocation, which may be responsible for an intestinal proinflammatory status and subsequent alpha-synuclein aggregation and propagation.6 7

Some features of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are similar to those of PD. Thus, their etiopathogenesis involves an anomalous immune response to specific microbiota that would trigger intestinal inflammatory activity in predisposed individuals unable to inhibit this inflammation and without the immunological tolerance characteristic of a healthy intestine.8 The few studies on the relationship between these diseases have published controversial results, with observations either of no association9 or of an increased risk of PD only among patients with Crohn’s disease,10 attributable to a genetic relationship between these diseases at different loci, as revealed in a genome-wide association study.11 Specifically, mutations in the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 gene, recently associated with Crohn’s disease, have revealed pleiotropy between this IBD and PD risk.12 Instead, a meta-analysis of the recent literature showed an increased risk of PD in the IBD population and the increased risk remained significant when analysing Crohn’s disease and ulcerous colitis subgroups.13

With this background, the objective of this study was to explore associations between PD and IBD treated with mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA)) or its derivative sulfasalazine, hereafter 5-ASA, because they could have a role in reducing the risk of PD.

Material and methods

A cross-sectional study was performed based on electronic drug prescription and dispensation records (Receta XXI) of the Andalusian Public Health System, which include 98% of all prescriptions in the region. Andalusia is located in southern Spain and is the most populated autonomous community in the country, with 8 402 000 inhabitants.

Subjects

All individuals aged ≥50 years with at least one drug dispensation during December 2014 were identified from the records. Three groups were formed: ‘possible PD’ group, including all who received an anti-Parkinson agent, such as levodopa in different formulations and/or dopaminergic agonist, excluding those only receiving a single low-dose dopaminergic agonist (ropinirole ≤1 mg; rotigotine ≤2 mg; pramipexole ≤0.26 mg; pergolide ≤1 mg; cabergoline ≤1 mg) and/or monoamine oxidase B inhibitor, including those exclusively treated with selegiline or rasagiline; ‘possible IBD’ group, including all receiving 5-ASA in its different formulations (mesalazine/mesalamine or 5-ASA and sulfasalazine); and ‘possible PD and IBD’, including those receiving both anti-Parkinson agent and 5-ASA.

Study variables

Membership of the possible PD group was the dependent variable, and membership of the possible IBD group, sex and age were the predictive variables.

Data gathering

Data were obtained from the computerised databases of the Andalusian Health Service Pharmacy and Benefit Support Department. Anonymity was preserved by masking clinical record numbers.

Data analysis

In a descriptive analysis, central tendency and dispersion measurements were calculated for quantitative variables and absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables, plotting the corresponding graphs. After applying the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to check data distribution normality, between-group comparisons were evaluated with the Mann-Whitney U for the quantitative variable (age) and with the χ2 test for categorical variables. After controlling for age and sex, the strength of between-group associations was established by constructing a multiple logistic regression model to estimate the OR and 95% CI. All tests were two-tailed, and p<0.05 was considered significant. R and SPSS V.21 statistical packages were used for the statistical analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved.

Results

During December 2014, 2 020 868 individuals aged ≥50 years were dispensed with at least one drug; their mean age was 67.9±11.8 years, 56% were female (mean of 68.6±11.5 years) and 44% were male (mean of 67.2±10.7 years). The study included 27 451 patients (mean age of 72.3±10.9 years, 51% female) with at least one dispensation of anti-Parkinson agent (possible PD) and/or 5-ASA (possible IBD) after excluding 24 patients with inadequate records (eg, missing data on age and/or sex) and 6 with unlikely PD (low-dose dopaminergic agonist (0.5 mg cabergoline in 1 case and 0.5 mg ropinirole in 5)); the mean age was slightly higher for the females than for the males (73.1±10.9 vs 71.4±10.8 years; p=0.0001).

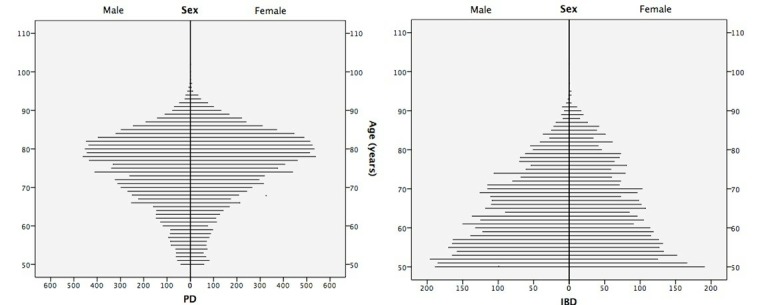

A total of 19 966 individuals were considered as possible PD (mean age of 75.4±9.3 years, 53% females) and 7485 as possible IBD (64.15±10.4 years, 47% females). Individuals with possible PD were older (p=0.0001) and more frequently female (p=0.0001) in comparison to those with possible IBD (figure 1). A group of 56 individuals (32 females) were considered both possible PD and possible IBD; their mean age was 75.7±8.1 years (range, 52–94 years), and they showed no differences in age (p=0.956) or sex (p=0.505) distribution with respect to the possible PD group.

Figure 1.

Population pyramid with age and sex distribution of the groups with possible inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and possible Parkinson’s disease (PD).

The prevalence of possible PD was 0.7% in the possible IBD group and 1% in those without this condition (table 1). Possible IBD showed a reduced risk for possible PD with OR of 0.75 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.98; p=0.036), rising to 0.94 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.23; p=0.657) after controlling for age and sex; stratification by age yielded an OR of 0.28 (95% CI 0.10 to 0.74; p=0.01) for individuals aged ≤65 years and 1.17 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.54; p=0.257) for those aged >65 years, after controlling for sex (table 2).

Table 1.

2×2 contingency table and prevalence of possible PD

| Without possible PD |

With possible PD |

Prevalence possible PD (%) |

|

| Without possible IBD |

1 993 473 | 19 966 | 1 |

| With possible IBD |

7485 | 56 | 0.7 |

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted risk of possible Parkinson’s disease in individuals with possible inflammatory bowel disease

| Variable | β1 | OR (95 % CI) | P value |

| ‘Possible PD’ | −0.28 | 0.75 (0.57 to 0.98) | 0.0362 |

| Adjusted model | |||

| Possible PD | −0.06 | 0.94 (0.72 to 1.23) | 0.657 |

| Possible PD ≤65 years | −1.28 | 0.28 (0.10 to 0.74) | 0.0103 |

| Possible PD >65 years | 0.16 | 1.17 (0.89 to 1.54) | 0.257 |

The bold values are statistically significant.

PD, Parkinson’s disease.

Discussion

The results of this cross-sectional study suggest that the presence of IBD and/or treatment with 5-ASA may play a protective role against PD development, especially among under 65-year olds. The pathogenesis of the two diseases may share certain features, including the role of enteric glial cells14–16 and inflammation,17 genetic factors (PD and Crohn’s disease),11 the protective effect of tobacco (PD and ulcerous colitis),18 the presence of proinflammatory flora and altered permeability with rupture of the intestinal barrier.6 7 In fact, the inflammatory condition and/or treatment with 5-ASA might have been expected to act as a risk rather than protective factor, unless they have some impact on the pathogenesis of this synucleinopathy.

Our results are similar to those of the recent case-control study of PD risk based on Medicare data; this group found an inverse association between IBD and PD, including both Crohn’s disease and ulcerous colitis. Similarly, there was an inverse association between PD and IBD-associated conditions, as well as IBD-associated surgical procedures and immunosuppressant use, even among beneficiaries without IBD. The authors suggest that IBD is associated with a lower risk of developing PD in the adjusted model for a population aged >65 years (OR=0.86; 95% CI 0.81 to 0.92).19

Conversely, a retrospective cohort study based on healthcare records found an increased risk of PD among IBD patients, especially those with Crohn’s disease, given that this association was not observed in the subgroup with ulcerous colitis (OR=0.94; 95% CI 0.49 to 1.84).10 Although these cases were not specified in our study, they can largely be considered to have ulcerous colitis, given reservations in clinical guidelines about the administration of 5-ASA in Crohn’s disease.20 In the aforementioned cohort study, there was a relative reduction in PD risk among patients with longer follow-up times, similar to observations in individuals with truncal vagotomy21 22 and in under 65-year olds, as in the present study.

Recently, three studies have been published describing a risk association between IBD and PD. In the Danish nationwide population cohort study, covering the period 1977–2014, found a significantly increased risk of PD when comparing patients with IBD with non-IBD (HR=1.22; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.35), especially among patients with ulcerative colitis (HR=1.35; 95% CI 1.20 to 1.52). However, in those patients diagnosed with IBD under 40 years of age and with prolonged follow-up >20 years, this increase was not statistically significant,23 suggesting, as we have previously referred, that IBD treatment may lessen the risk of PD. In a similar way, a Nationwide Swedish Cohort Study, covering the period 2002–2014, found that IBD is associated with an increased risk of PD; however, IBD patients who developed PD were much older at the end of follow-up (88% vs 35% at age ≥60 years; p=0.001) and more likely to never have received thiopurine or anti-Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) compared with those without PD (88% vs 66%; p=0.001), 80% of PD events occurred in patients with IBD onset ≥60 years and the relative risk of future PD in IBD was highest among patients diagnosed with IBD at age 60 years or older. Authors suggested a potential protective effect of selective IBD-directed therapies, thiopurines, or anti-TNF-α on PD, as IBD patients never exposed to thiopurines or anti-TNF were 60% more likely to develop PD (HR=1.6; 95% CI 1.2 to 2.2) than their matched reference individuals,24 raising again the protective effect of the treatment of IBD on the development of PD. In a retrospective cohort study, based on the Market-Scan Commercial and Medicare databases, a higher incidence of PD was observed among patients with IBD than among individuals without IBD; the authors found a statistically significant 28% increase in the incidence of PD among patients with IBD compared with the unaffected matched controls. Conversely, they observed a markedly lower PD incidence rate (0.08 per 1000 patient-years) among patients with IBD who were exposed to anti-TNF therapy compared with patients without exposure (0.76 per 1000 patient-years), which means a 78% reduction in the PD incidence rate,25 a risk reduction in the same range as that found in our patients treated with 5-ASA.

Despite the contradictory associations between both processes, two studies find a reduction in the risk of PD related to the use of immunomodulators,19 25 although they do not describe the degree of exposure to 5-ASA. It is presumable that those with a more active disease and therefore candidates for immunomodulators therapies will have had a greater exposure to 5-ASA, but it is also possible that those treated exclusively with 5-ASA have a more benign inflammatory disease.

5-ASA drugs are the first-line treatment in ulcerous colitis.20 26 Their action mechanism is not fully elucidated but is considered to include (1) anti-inflammatory activity or inhibition of the local synthesis of prostaglandins and leukotrienes27; (2) reduction in nitric oxide and IL-6 production and an antiapoptotic effect, diminishing phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinases, for example, p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK)28; and (3) action on the microbiota, producing qualitative and quantitative changes in its composition.29

In PD, alpha-synuclein aggregates are known to be present in the intestine some years before the onset of motor symptoms,4 5 especially in certain structures such as the vermiform appendix.30 Local action mechanisms of 5-ASA described above may affect progression of the synucleinopathy, given that they may act on etiopathogenetic mechanisms that would activate microglia, associated with certain microbiota and bacterial membrane lipopolysaccharides or endogenous factors (eg, JNK and p38).31–33

In a recent murine model with alpha-synuclein overexpression, transplantation from PD patients of faecal matter with greater short-chain fatty-acid content was followed by microglial activation, an increase in inflammation mediators (TNF-α and IL-6) and in alpha-synuclein aggregation and propagation, a poorer execution of motor tests, and even constipation; these changes were reduced by treatment with minocycline,34 suggesting that other drug groups, such as 5-ASA, may have a similar effect.

This study has limitations related to the utilisation of a drug dispensation record, subjects therefore not be considered representative of the general population. The resulting ORs may be overestimated, because the prevalence of both diseases was over-represented but in an unequal manner, being higher for PD in the study population than in the general population and only slightly higher for IBD. Cross-sectional drug dispensation studies are more likely to include patients with PD than with IBD due to their older age and more frequent polymedication and because some biological and immunosuppressive therapies received by IBD patients in the hospital are not included in the dispensary records. Furthermore, individuals treated with 5-ASA are a subgroup of patients with IBD and ulcerous colitis, mainly in those with active disease. We did not control for the possibility of a group of patients receiving combined maintenance therapy (5-ASA and other drugs). There is also a potential classification error related to the selection of proxy variables, given that the diseases under study were identified according to the medication received. Notably, dopaminergic drugs are prescribed, although much less frequently, for diseases other than PD (atypical parkinsonism, chronic adult hydrocephaly, restless legs syndrome and so on); however, this is unlikely to have affected the validity of our results given the large sample size.

Conclusions

A lower risk of PD was observed in individuals with IBD aged ≤65 years and treated with 5-ASA, which may be, as hypothesis, related to a theoretical pharmacological effect on alpha-synuclein aggregation and propagation that could reduce or delay PD onset in at-risk populations. The advantages of 5-ASA medication include its relatively low cost and lack of absorption. Within the limitations of the methodology applied, further experimental research with animal models and new longitudinal studies are warranted, given the important scientific and therapeutic implications of these findings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JPR, FES and VCA contributed conception and design of the study. MJPN, MJPV and CJMN organised the database. FES and AMC performed the statistical analysis. JPR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FES, CJMN, MJCT and MRGG wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Granada (CEI-GRANADA).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data from the study.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Braak H, Rüb U, Gai WP, et al. Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: possible routes by which vulnerable neuronal types may be subject to neuroinvasion by an unknown pathogen. J Neural Transm 2003;110:517–36. 10.1007/s00702-002-0808-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pan-Montojo F, Anichtchik O, Dening Y, et al. Progression of Parkinson’s disease pathology is reproduced by intragastric administration of rotenone in mice. PLoS One 2010;5:e8762 10.1371/journal.pone.0008762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holmqvist S, Chutna O, Bousset L, et al. Direct evidence of Parkinson pathology spread from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain in rats. Acta Neuropathol 2014;128:805–20. 10.1007/s00401-014-1343-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hilton D, Stephens M, Kirk L, et al. Accumulation of α-synuclein in the bowel of patients in the pre-clinical phase of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 2014;127:235–41. 10.1007/s00401-013-1214-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Minguez-Castellanos A, Chamorro CE, Escamilla-Sevilla F, et al. Do alpha-synuclein aggregates in autonomic plexuses predate Lewy body disorders?: a cohort study. Neurology 2007;68:2012–8. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264429.59379.d9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelly LP, Carvey PM, Keshavarzian A, et al. Progression of intestinal permeability changes and alpha-synuclein expression in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2014;29:999–1009. 10.1002/mds.25736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Forsyth CB, Shannon KM, Kordower JH, et al. Increased intestinal permeability correlates with sigmoid mucosa alpha-synuclein staining and endotoxin exposure markers in early Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 2011;6:e28032–10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sheehan D, Moran C, Shanahan F. The microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol 2015;50:495–507. 10.1007/s00535-015-1064-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rugbjerg K, Friis S, Ritz B, et al. Autoimmune disease and risk for Parkinson disease: a population-based case-control study. Neurology 2009;73:1462–8. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c06635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lin JC, Lin CS, Hsu CW, et al. Association Between Parkinson’s Disease and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: a Nationwide Taiwanese Retrospective Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:1049–55. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nalls MA, Saad M, Noyce AJ, et al. Genetic comorbidities in Parkinson’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:831–41. 10.1093/hmg/ddt465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hui KY, Fernandez-Hernandez H, Hu J, et al. Functional variants in the LRRK2 gene confer shared effects on risk for Crohn’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Sci Transl Med 2018;10:eaai7795 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai7795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhu F, Li C, Gong J, et al. The risk of Parkinson’s disease in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 2019;51:38–42. 10.1016/j.dld.2018.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clairembault T, Leclair-Visonneau L, Neunlist M, et al. Enteric glial cells: new players in Parkinson’s disease? Mov Disord 2015;30:494–8. 10.1002/mds.25979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ochoa-Cortes F, Turco F, Linan-Rico A, et al. Enteric glial cells: a new frontier in neurogastroenterology and clinical target for inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:433–49. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Capoccia E, Cirillo C, Gigli S, et al. Enteric glia: a new player in inflammatory bowel diseases. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2015;28:443–51. 10.1177/0394632015599707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Devos D, Lebouvier T, Lardeux B, et al. Colonic inflammation in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 2013;50:42–8. 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Derkinderen P, Shannon KM, Brundin P. Gut feelings about smoking and coffee in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2014;29:976–9. 10.1002/mds.25882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Camacho-Soto A, Gross A, Searles Nielsen S, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and risk of Parkinson’s disease in Medicare beneficiaries. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018;50:23–8. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2011;60:571–607. 10.1136/gut.2010.224154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu B, Fang F, Pedersen NL, et al. Vagotomy and Parkinson disease: a Swedish register-based matched-cohort study. Neurology 2017;88:1996–2002. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Svensson E, Horváth-Puhó E, Thomsen RW, et al. Vagotomy and subsequent risk of Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 2015;78:522–9. 10.1002/ana.24448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Villumsen M, Aznar S, Pakkenberg B, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease increases the risk of Parkinson’s disease: a Danish nationwide cohort study 1977–2014. Gut 2018;0:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weimers P, Halfvarson J, Sachs MC, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and parkinson’s disease: a nationwide swedish cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:111–23. 10.1093/ibd/izy190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peter I, Dubinsky M, Bressman S, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy and incidence of parkinson disease among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:939–46. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ford AC, Achkar JP, Khan KJ, et al. Efficacy of 5-aminosalicylates in ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:601–16. 10.1038/ajg.2011.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Greenfield SM, Punchard NA, Teare JP, et al. Review article: the mode of action of the aminosalicylates in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1993;7:369–83. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1993.tb00110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qu T, Wang E, Jin B, et al. 5-Aminosalicylic acid inhibits inflammatory responses by suppressing JNK and p38 activity in murine macrophages. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2017;39:45–53. 10.1080/08923973.2016.1274997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Andrews CN, Griffiths TA, Kaufman J, et al. Mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) alters faecal bacterial profiles, but not mucosal proteolytic activity in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:374–83. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04732.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gray MT, Munoz DG, Gray DA, et al. Alpha-synuclein in the appendiceal mucosa of neurologically intact subjects. Mov Disord 2014;29:991–8. 10.1002/mds.25779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang W, Gao JH, Yan ZF, et al. Minimally toxic dose of lipopolysaccharide and α-synuclein oligomer elicit synergistic dopaminergic neurodegeneration: role and mechanism of microglial NOX2 activation. Mol Neurobiol 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moussaud S, Malany S, Mehta A, et al. Targeting α-synuclein oligomers by protein-fragment complementation for drug discovery in synucleinopathies. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2015;19:589–603. 10.1517/14728222.2015.1009448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilms H, Rosenstiel P, Romero-Ramos M, et al. Suppression of MAP kinases inhibits microglial activation and attenuates neuronal cell death induced by alpha-synuclein protofibrils. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2009;22:897–909. 10.1177/039463200902200405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sampson TR, Debelius JW, Thron T, et al. Gut Microbiota Regulate Motor Deficits and Neuroinflammation in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Cell 2016;167:1469–80. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.