Abstract

Objectives

Copeptin and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (HS-cTn) assays improve the early detection of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). Their sensitivities may, however, be reduced in very early presenters.

Setting

We performed a post hoc analysis of three prospective studies that included patients who presented to the emergency department for chest pain onset (CPO) of less than 6 hours.

Participants

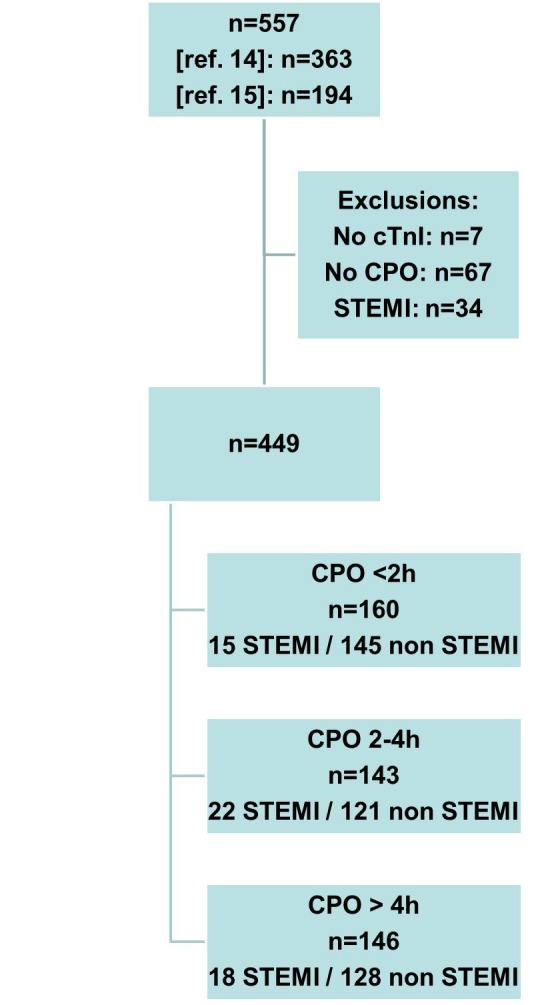

449 patients were included, in whom 12% had NSTEMI. CPO occurred <2 hours from ED presentation in 160, between 2 and 4 hours in 143 and >4 hours in 146 patients. The prevalence of NSTEMI was similar in all groups (9%, 13% and 12%, respectively, p=0.281).

Measures

Diagnostic performances of HS-cTn and copeptin at presentation were examined according to CPO. The discharge diagnosis was adjudicated by two experts, including cardiac troponin I (cTnI). HS-cTn and copeptin were blindly measured.

Results

Diagnostic accuracies of cTnI, cTnI +copeptin and HS-cardiac troponin T (HS-cTnT) (but not HS-cTnT +copeptin) lower through CPO categories. For patients with CPO <2 hours, the choice of a threshold value of 14 ng/L for HS-cTnT resulted in three false negative (Sensitivity 80%(95% CI 51% to 95%); specificity 85% (95% CI 78% to 90%); 79% of correctly ruled out patients) and that of 5 ng/L in two false negative (sensitivity 87% (95% CI 59% to 98%); specificity 58% (95% CI 50% to 66%); 52% of correctly ruled out patients). The addition of copeptin to HS-cTnT induced a decrease of misclassified patients to 1 in patients with CPO <2 hours (sensitivity 93% (95% CI 66% to 100%); specificity 41% (95% CI 33% to 50%)).

Conclusion

A single measurement of HS-cTn, alone or in combination with copeptin at admission, seems not safe enough for ruling out NSTEMI in very early presenters (with CPO <2 hours).

Trial registration number

DC-2009–1052

Keywords: high sensitive cardiac troponin, chest pain, non st-elevation acute myocardial infarction, copeptin, very early presenters, chest pain onset

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Focus on very early chest pain presenters that was not performed before.

Small numbers of very early chest pain presenters, although the data grouping of three previous studies.

A single measurement of troponin at admission was considered for the analysis, but not its kinetics.

The gold-standard diagnosis was based on a non-high-sensitivity cardiac troponin.

Introduction

The management of patients with acute chest pain at the emergency department (ED) is a major health problem and an adequate ruling out process for non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) is crucial. Cardiac troponin (cTn) measurement with conventional assays and more recent high-sensitivity cTn assays (HS-cTn, either isoforms HS-cTnI or HScTnT) are current diagnostic tools for the assessment of these patients.1 The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines proposed a rapid rule out strategy using low HS-cTn values (ie, values below the limit of detection of the assay (LoD)) as decisional threshold for ruling out NSTEMI.1 The accuracy of a rapid 0/1-hour algorithm has also been recently demonstrated in patients with chest pain onset (CPO) <6 hours2 and is endorsed by the latest ESC guidelines.1 In this analysis, the authors indicated that using a single HS-cardiac troponin T (HS-cTnT) cut-off value of 14 ng/L at presentation resulted in 88.7% sensitivity and 97.3% negative predictive value (NPV), but that this single assay strategy was less effective than the combination of absolute level of HS-cTnT measured at presentation and again at 1 hour, combined with the absolute difference between the two levels.2

However, in very early presenters, such rapid and efficient triage at presentation may be uncertain.3 Indeed, very early presenters, defined as having chest pain <2 hours, are considered by some authors as highly vulnerable as they may not present all symptoms and signs and thus be exposed to a higher risk of misdiagnosis and therefore worse outcome4; the application of a rapid algorithm to these patients may lead to early discharge within 3 hours from ED admission. Recently, a meta-analysis (based on 11 studies) indicated that a single HS-cTnT concentration below the LoD may successfully rule out acute MI (AMI).5 However, concerns have been raised about the safety of a single measurement rule out protocol performed at presentation in early presenters.6 7

Copeptin (in association with cTn) assays improve the early detection of NSTEMI.8–12 Indeed, a randomised controlled trial demonstrated the safety of early discharge using a single combination of copeptin +cTn at presentation for patients with CPO <6 hours.13

The present study aimed to assess the diagnostic performance of HS-cTn and copeptin as a single measurement at admission in very early ED presenters with suspected NSTEMI.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

The study is a post hoc analysis of three French prospective clinical studies (already published) of cardiac biomarker testing, each to explore the usefulness of copeptin and/or HS-cTnT testing in patients who presented to the ED with acute chest pain of less than 6 hours.14 15 However, none of these studies evaluated the influence of CPO value on diagnostic performances. All three trials had comparable inclusion/exclusion criteria and gathered similar clinical information (table 1). Patients requiring renal replacement therapy were excluded. Recommendations of the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy initiative were applied.16

Table 1.

Main characteristics of original study designs

| Sebbane et al 14 | Chenevier-Gobeaux et al 15 | |

| Inclusion criteria | Prospective cohort of emergency department (ED) patients with chest pain onset <12 hours. | Consecutive patients, >18 years old, admitted to the ED or to the Intensive Care Unit by prehospital emergency ambulances. |

| Exclusion criteria | Patients with traumatic causes of chest pain. | Patients <18 years old. Acute or chronic renal failure requiring dialysis. |

| Plasma sampling and storage | Heparinised and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid blood collection. Storage at −80°C for later analysis. | Heparinised blood collection after routine cardiac troponin I measurement. Storage at −40°C until HS-cTnT and copeptin measurement. |

| Registration no/name | French Health Ministry (no. DC-2009–1052). | French Local Ethic comity « Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile-de-France » III (Hôpital Cochin) et VI (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Pitié-Salpétrière). |

| Consent | Written informed consent. | Cochin Hospital: waiver of informed consent was authorised. Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital: informed consent was granted. |

Patient involvement

The development of the research question was not informed by patients. Patients were not involved in the design of this study. Patients were not involved in the recruitment to and conduct of the study. There was no results dissemination to study participants.

Routine assessment

All patients underwent an initial clinical evaluation (including clinical history, physical examination, 12-lead ECG, pulse oximetry, routine blood tests and chest X-ray). Conventional cardiac troponin I (cTnI) was measured on a venous blood collection performed at presentation and, if required, repeated after 3–9 hours, as clinically indicated.17 The CPO, defined as the delay from symptom onset to presentation, was recorded, based on patient history/declaration. When history was incomplete or inconsistent, CPO was not recorded and patient was excluded from the analysis (see flow chart, figure 1). Based on all clinical, biological (including cTnI value, but not HS-cTnT and copeptin values which were blindly measured) and imaging results, a decision was made by the attending physician to admit or discharge the patient, as well as medical therapy and revascularisation if indicated. Attending emergency physicians and cardiologists were blinded to the results of HS-cTnT and copeptin, and biologists were blinded to the suspected diagnosis at presentation.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the studied population. CPO, chest pain onset; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Patients with no cTnI results and/or no recorded CPO value and patients with a final diagnosis of STEMI were excluded (see flow chart, figure 1).

Gold-standard diagnosis

The gold-standard diagnosis was adjudicated by two independent experts (emergency physician and cardiologist) who reviewed all available medical records (including patient history, physical findings, laboratory results including cTnI value and radiological testing, ECG, echocardiography, cardiac exercise test, coronary angiography, summary chart at discharge) pertaining to the patient from the time of ED presentation to 30-day follow-up. Experts were blind to copeptin and HS-cTnT results. In the event of diagnostic disagreement, cases were reviewed and adjudicated in conjunction with a third expert.

AMI was diagnosed according to the universal definition that was in force at the time of inclusions and adapted to the use of a conventional cTn.18 Thus, patients with a cTnI increase (or a rise/fall pattern) above the 10% coefficients of variation (CV) threshold, associated with at least one of the following: symptoms of myocardial ischaemia, new ST-T changes or new Q wave on ECG, imaging of new loss of viable myocardium or normal cTnI on admission were classified as having an MI (STEMI with an ST elevation in at least two continuous leads on ECG or new onset of left bundle branch block or NSTEMI). Patients with STEMI were excluded from the analysis, based on ST elevation observed on the ECG (see flow chart, figure 1). Patients were classified according to the CPO, <2 hours, from 2 to 4 hours and >4 hours; those with a CPO <2 hours were considered as very early presenters.

Unstable angina (UA) diagnosis was adjudicated in patients with history or clinical symptoms consistent with acute coronary syndrom but without ST-T wave changes on the ECG and without change of cTn on serial testing. Other diagnostic categories besides NSTEMI and UA were non-ACS (eg, stable angina, myocarditis, arrhythmias, heart failure, pulmonary embolism and chest pain of unknown origin). UA and non-ACS chest pain were considered as non-NSTEMI in our analysis.

Troponin measurements

Plasma cTnI concentrations were routinely measured on an X-pand HM analyzer, using the cTnI immunoassay (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Newark, Connecticut, USA) in two EDs (Cochin and La Pitié Salpêtrière Hospitals). The LoD was 0.04 µg/L (40 ng/L). The limit of quantitation (LoQ), that is, the 10% imprecision point (or 10% CV), which is the lowest cTn concentration that can be reproducibly measured with a between-run CV of ≤10%, was 0.14 µg/L (140 ng/L). The 99th percentile of the assay was 0.07 µg/L (70 ng/L), with CVs between 15% and 22%. The measuring range was 0.04–40 µg/L (40–40 000 ng/L), and the imprecision values across the measuring range were below 10%.

In Bicêtre and in Montpellier hospitals, plasma cTnI concentrations were routinely measured on an Access analyser (Beckman Coulter, Brea, California, USA). According to the manufacturer’s data, the LoD was 0.01 µg/L (10 ng/L), the 20% point on the imprecision curve was 0.02 µg/L (20 ng/L). The LoQ/10% CV was 0.04 µg/L (40 ng/L). The 99th percentile of the assay was 0.04 µg/L (40 ng/L). The measuring range was 0.01–100 µg/L (10–100 000 ng/L), and the imprecision values across the measuring range were below 10%.

After routine cTnI measurement, plasma samples were aliquoted and frozen (−40°C) until HS-cTnT and copeptin measurement.

Hs-cTnT was measured in heparinised collected samples, on an Elecsys2010 analyser (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). The limit of blank (LoB) was 3 ng/L, the LoD was 5 ng/L and the 99th percentile was 14 ng/L. The measuring range was 3–10 000 ng/L. In our laboratory, CVs obtained in Roche quality controls containing 27.5 and 2360 ng/L of cTnT were 3.6% and 2.8% (between-run precision) and 1.4% and 0.4% (within-run precision). Of note, the LoD is measured with a between-run CV of >10%, while the 99th percentile is a precise concentration (CV <10%).7 HS-cTnT determinations were performed blinded to the clinical assessment of the emergency physicians.

Copeptin measurement

Copeptin was measured in heparinised blood samples collected on admission. The assay was performed on a KRYPTOR analyser using ThermoFisher Scientific sandwich immunoluminometric assay (B.R.A.H.M.S Copeptin KRYPTOR, B.R.A.H.M.S Aktiengesellschaft, Hennigsdorf, Germany). The assay principle is based on TRACE technology (Time-Resolved Amplified Cryptate Emission). The lower detection limit is 4.8 pmol/L, and the functional assay sensitivity (20% CV value) is <12 pmol/L (data from manufacturer, recommended threshold value for this method). Copeptin determinations were performed blinded to the clinical assessment of the emergency physicians.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means±SD, and categorical variables are expressed as numbers (percentage). Continuous variables were compared by using the Kruskal-Wallis test, and categorical variables were assessed using Pearson’s χ2 test. Number of misclassified patients and number of correctly ruled out patients were collected for each threshold strategy, and correspond to the false negative and the true positive patients, respectively.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to assess the sensitivity and specificity, positive predictive value and NPV throughout the concentrations of cTnI, HS-cTnT and copeptin for the diagnosis of NSTEMI, and according to the CPO. cTn and copeptin values were log-transformed before combination for ROC analysis. For cTnI values, as they were obtained from two non-standardised methods, values were normalised by factorising to the 99th percentile of the method prior to ROC analysis in order to remove any bias due to methodological differences.

Diagnostic thresholds that were used for classification of the data are:

For cTnI, the LoQ values: 0.04 µg/L (40 ng/L) for Bicêtre and Montpellier hospitals, 0.14 µg/L (140 ng/L) for other sites.

For HS-cTnT, The LoB (3 ng/L), the LoD (5 ng/L) and the 99th percentile (14 ng/L).

For copeptin, the manufacturer’s recommended threshold at 12 pmol/L.

All data are presented with their 95% CIs. All hypothesis testing was two tailed, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc (MedCalc Software, V.12.4.0.0, Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

Characteristics of the studied population

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the studied population. Briefly, in the total cohort mean age was 58±17 years, and included more males. A gold-standard diagnosis of NSTEMI was adjudicated in 55 patients (12%). Delay from CPO to ED admission was <2 hours in 160 (36%) patients, was from 2 to 4 hours in 143 (32%) and was >4 hours (and below 6 hours) in 146 (32%) patients. Very early presenters with NSTEMI (n=15) tended to be older than those without NSTEMI (n=145) (65 vs 55 years old), were more frequently hospitalised (93% vs 58%), and also more frequently underwent diagnostic coronary angiography (73% vs 27%).

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the studied population

| All patients | CPO <2 hours (very early presenters) |

CPO 2–4 hours | CPO 4–6 hours | |

| n | 449 | 160 | 143 | 146 |

| Age (years) | 58±17 | 57±16 | 59±17 | 58±17 |

| Men | 281 (63) | 101 (63) | 96 (67) | 84 (58) |

| Medical history | ||||

| Familial history of CAD, present/total (%)* | 104/301 (35) | 63/147 (43) | 26/90 (29) | 15/64 (23) |

| Personal history of CAD Dyslipidaemia Diabetes Smoking Hypertension |

120 (27) 168 (37) 67 (15) 176 (39) 158 (35) |

38 (24) 61 (38) 20 (13) 72 (45) 52 (33) |

42 (29) 57 (40) 22 (15) 51 (37) 58 (41) |

40 (27) 50 (34) 25 (17) 53 (36) 48 (33) |

| Outcome | ||||

| Coronary angiography Admission |

131 (29) 256 (57) |

49 (31) 98 (61) |

46 (32) 91 (63) |

36 (25) 67 (46) |

| Final diagnostic | ||||

| NSTEMI Other |

55 (12) 394 (88) |

15 (9) 145 (91) |

22 (13) 121 (85) |

18 (12) 128 (88) |

Results are expressed in mean±SD or in number (percentage).

*Missing data exist for this variable.

CAD, coronary artery disease; CPO, chest pain onset; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Diagnostic performances according to CPO

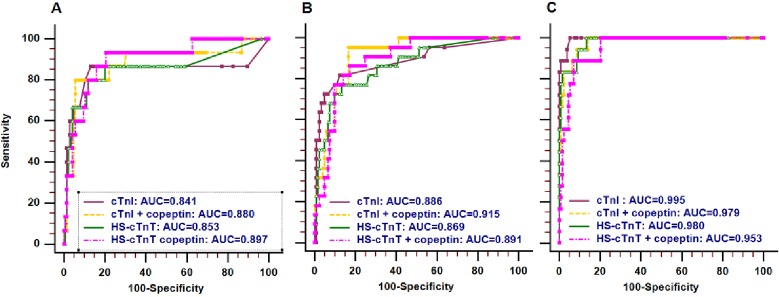

ROC curves of cTn for the diagnosis of NSTEMI, alone or in combination with copeptin, are presented in figure 2. Diagnostic accuracies of cTnI, cTnI +copeptin and HS-cTnT are reduced when time to CPO gets less, as indicated by estimated area under the ROC curve (AUCs) and their 95% CIs (table 3). The AUCs of HS-cTnT +copeptin were not different through the CPO categories.

Figure 2.

ROC curves of cTn for the diagnosis of NSTEMI, alone or in combination with copeptin. (A) CPO <2 hours; (B) CPO 2–4 hours; (C) CPO >4 hours. AUC, area under the ROC curve; cTn, cardiac troponin; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; CPO, chest pain onset; HS-cTnT, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Table 3.

AUC values according to CPO category

| Biomarker | AUC | 95% CI | |

| CPO <2 hours (very early presenters) | cTnI | 0.841 | 0.775 to 0.894 |

| cTnI+copeptin | 0.880 | 0.819 to 0.926 | |

| HS-cTnT | 0.853 | 0.789 to 0.904 | |

| HS-cTnT+copeptin | 0.897 | 0.840 to 0.940 | |

| CPO 2–4 hours | cTnI | 0.886 | 0.823 to 0.933 |

| cTnI+copeptin | 0.915 | 0.857 to 0.955 | |

| HS-cTnT | 0.869 | 0.802 to 0.919 | |

| HS-cTnT+copeptin | 0.891 | 0.829 to 0.937 | |

| CPO >4 hours | cTnI | 0.995 | 0.965 to 1.000 |

| cTnI+copeptin | 0.979 | 0.940 to 0.995 | |

| HS-cTnT | 0.980 | 0.942 to 0.996 | |

| HS-cTnT+copeptin | 0.953 | 0.905 to 0.981 |

AUC, area under the ROC curve; CPO, chest pain onset; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; HS-cTnT, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T.

Diagnostic performances of cTn, alone or in combination with copeptin, and using different decisional thresholds, are presented in table 4.

Table 4.

Diagnostic performances for NSTEMI according to CPO

| CPO | Biomarker | Threshold | Sensitivity (%, (95% CI)) |

Specificity (%, (95% CI)) |

Negative predictive value (%, (95% CI)) | Positive predictive value (%, (95% CI)) | Misdiagnosed (*) (n) | Correctly ruled out, n (%) |

| <2 hours (very early presenters) (n=160) |

cTnI cTnI+copeptin HS-cTnT HS-cTnT+copeptin |

LoQ† LoQ† and 12 pmol/L 14 ng/L 5 ng/L 3 ng/L 14 ng/L and 12 pmol/L 5 ng/L and 12 pmol/L 3 ng/L and 12 pmol/L |

73 (45 to 91) 87 (59 to 98) 80 (51 to 95) 87 (59 to 98) 87 (58 to 98) 93 (66 to 100) 93 (66 to 100) 93 [66 to 100] |

97 (92 to 99) 60 (52 to 68)‡ 85 (78 to 90)‡ 58 (50 to 66)‡§ 40 (32 to 49)‡§ 54 (46 to 62)‡§ 41 (33 to 50)‡§ 25 (19 to 34)‡§ |

97 (92 to 99) 98 (92 to 100) 98 (93 to 100) 98 (92 to 100) 97 (88 to 99) 99 (93 to 100) 98 (89 to 100) 97 (85 to 100) |

73 (45 to 91) 18 (7 to 24)‡ 35 (20 to 53) 18 (10 to 29)‡ 13 (7 to 22)‡ 18 (10 to 29)‡ 14 (8 to 23)‡ 12 (7 to 19)‡ |

4 2 3 2 2 1 1 1 |

141 (88) 87 (54)‡ 123 (79)‡ 84 (52)‡§ 58 (36)‡§ 79 (49)‡§ 59 (37)‡§ 37 (23)‡§ |

| 2–4 hours (n=143) |

cTnI cTnI+copeptin HS-cTnT HS-cTnT+copeptin |

LoQ† LoQ† and 12 pmol/L 14 ng/L 5 ng/L 3 ng/L 14 ng/L and 12 pmol/L 5 ng/L and 12 pmol/L 3 ng/L and 12 pmol/L |

73 (50 to 89) 95 (75 to 100) 77 (54 to 91) 91 (70 to 98) 96 (75 to 100) 95 (75 to 100) 100 (82 to 100) 100 (82 to 100) |

95 (89 to 98) 57 (48 to 66)‡ 79 (71 to 86)‡ 55 (46 to 64)‡§ 45 (36 to 54)‡§ 50 (41 to 59)‡§ 35 (27 to 44)‡§ 29 (21 to 38)‡§ |

95 (89 to 98)¶ 99 (92 to 100) 95 (88 to 98)¶ 97 (89 to 100) 98 (89 to 100) 99 (91 to 100) 100 (90 to 100) 100 (88 to 100) |

73 (50 to 89) 29 (19 to 41)‡ 40 (26 to 56) 27 (18 to 39)‡ 24 (16 to 34)‡ 25 (17 to 36)‡ 22 (15 to 32)‡ 20 (14 to 30)‡ |

6 1 5 2 1 1 0 0 |

115 (80) 69 (48)‡ 96 (67)‡** 67 (47)‡§ 54 (38)‡§ 58 (41)‡§ 42 (29)‡§ 35 (25)‡§ |

| >4 hours (n=146) |

cTnI cTnI+copeptin HScTnT HS-cTnT+copeptin |

LoQ† LoQ † and 12 pmol/L 14 ng/L 5 ng/L 3 ng/L 14 ng/L and 12 pmol/L 5 ng/L and 12 pmol/L 3 ng/L and 12 pmol/L |

100 (77 to 100) 100 (77 to 100) 100 (78 to 100) 100 (78 to 100) 100 (78 to 100) 100 (78 to 100) 100 (78 to 100) 100 (78 to 100) |

96 (91 to 99) 59 (50 to 68)‡ 87 (80 to 92)‡ 60 (51 to 68)‡§ 52 (43 to 61)‡§ 55 (46 to 64)‡§ 40 (32 to 49)‡§ 34 (26 to 43)‡§ |

100 (96 to 100) 100 (94 to 100) 100 (96 to 100) 100 (94 to 100) 100 (96 to 100) 100 (94 to 100) 100 (91 to 100) 100 (96 to 100) |

77 (54 to 91) 25 (16 to 37)‡ 51 (34 to 68) 35 (23 to 50)‡ 23 (14 to 34)‡ 24 (15 to 35)‡ 19 (12 to 29)‡ § 18 (11 to 27)‡ § |

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 |

122 (85) 75 (54)‡ 111 (77) 77 (53)‡§** 67 (47)‡§ 70 (49)‡§ 51 (35)‡§ 43 (30)‡§ |

*False negative patients.

†0.04 µg/L (40 ng/L) for Bicêtre and Montpellier hospitals, 0.14 µg/L (140 ng/L) for other sites.

‡P<0.05 versus cTnI alone.

§P<0.05 versus HS-cTnT <14 ng/L alone.

¶P<0.05 versus delay >4 hours.

**P<0.05 versus delay <2 hours.

CPO, chest pain onset; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; HS-cTnT, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; LoQ, limit of quantitation; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

In very early presenters (CPO <2 hours), a single value of cTnI alone had low sensitivity (73% (95% CI 73% to 91%)) but high specificity (97% (95% CI 92% to 99%)), and misclassified 4 of 15 NSTEMI patients. However, this strategy could correctly rule out 141 patients (88%). Combining copeptin with cTnI increases sensitivity, and lowers the number of misdiagnosed patients from 4 to 2, but significantly lowers the rate of ruled out patients from 88% to 54% (table 4). Of note, addition of copeptin also significantly lowered specificity. At a threshold of 14 ng/L, HS-cTnT had low sensitivity (80% (95% CI 59% to 98%)), misclassified 3 NSTEMI patients but could correctly rule out 123 (79%) patients, which is less than using cTnI. The sensitivity of HS-TnT alone is likely to be suboptimal in early presenters, but can be improved by using a lower threshold for positivity or adding copeptin (but this is accompanied with a marked loss of specificity). The addition of copeptin induced a decrease in misclassified patients from 2 to 1, either with an HS-cTnT threshold at 14 or at 5 ng/L. This ultimate misdiagnosed NSTEMI patient with CPO <2 hours who presented with all undetectable biomarkers was a 44-year-old woman with a history of smoking and no CV risk factors; the CPO was 45 min before hospital admission (table 5).

Table 5.

Potentially misdiagnosed patients with low cTn thresholds and copeptin

| Sex | Age | Dyslipidaemia | Smoke | Diabetes | Hypertension | Personal history of CAD | Chest pain since | CPO category | cTnI | HS-cTnT | Copeptin |

| M | 89 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 1 hour 15 min | <2 hours (very early presenters) | 0.04 µg/L (40 ng/L) | 44.9 ng/L | 208.7 pmol/L |

| M | 86 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | 30 min | 0.06 µg/L (60 ng/L) | 11.3 ng/L | 77.2 pmol/L | |

| W | 35 | No | No | No | No | No | 50 min | 0.01 µg/L (10 ng/L) | <3 ng/L | 54.7 pmol/L | |

| W | 44 | No | Yes | No | No | No | 45 min | 0.01 µg/L (10 ng/L) | <3 ng/L | 10.7 pmol/L | |

| W | 74 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | 3 hours | 2–4 hours | 0.04 µg/L (40 ng/L) | 8.8 ng/L | 10.7 pmol/L |

| M | 34.2 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | 2 hours 35 min | 0.04 µg/L (40 ng/L) | <3 ng/L | 23.5 pmol/L | |

| M | 55 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 3 hours 50 min | 0.02 µg/L (20 ng/L) | 6 ng/L | 25.9 pmol/L | |

| M | 34 | No | Yes | No | No | No | 3 hours 15 min | 0.01 µg/L (10 ng/L) | 4 ng/L | 52.4 pmol/L | |

| M | 61 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 3 hours | 0.03 µg/L (30 ng/L) | 19.7 ng/L | 27.2 pmol/L | |

| M | 59 | No | No | No | No | No | 2 hours 45 min | 0.04 µg/L (40 ng/L) | 10.1 ng/L | 241.8 pmol/L |

CAD, coronary artery disease; CPO, chest pain onset; cTn, cardiac troponin; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; M, men; W, women.

In patients with CPO 2–4 hours, results are similar to those observed in very early presenters, although the number of misclassified patients was different (table 4). Adding copeptin to cTnI induced a decrease of misclassified patients from 5 to 1 for an HS-cTnT threshold at 14 ng/L, and from 2 to 0 for an HS-cTnT threshold at 5 ng/L. In particular, combining copeptin to the LoD (5 ng/L) of HS-cTnT reached 100% sensitivity of the test. Similar performance was observed using the LoB (3 ng/L) of HS-cTnT. Indeed, all NSTEMI patients with CPO 2–4 hours had a detectable HS-cTnT and/or an elevated copeptin. In this subgroup again, the use of copeptin lowered significantly the specificity of the test.

As expected, in patients with CPO >4 hours, all patients had quantitative cTnI and detectable HS-cTnT. No patient was misclassified. The addition of copeptin in this subgroup had no effect on sensitivity or misclassified patients.

Potential misdiagnosed NSTEMI

Characteristics of potential misdiagnosed NSTEMI patients are detailed in table 5. All potentially missed NSTEMI in the very early presenters population had a CPO <1 hour. We found no distinguishing characteristics in misclassified patients when comparing to correctly diagnosed patients in terms of age, sex and cardiovascular risks, in each CPO category. Of note, when patients with STEMI were included in our analysis, results were comparable (data not shown).

Discussion

Our results indicate that diagnostic performances of HS-cTnT values at admission, alone or combined with copeptin, are reduced in the subgroup of patients with shorter CPO. Emergency physicians may not rule out NSTEMI in very early presenters with a single low value of HS-cTnT and/or copeptin at presentation.

Our studied population included one-third of early presenters, and this proportion is similar to that found by Boeddinghaus et al (26% of patients presented within 2 hours from CPO),4 by Keller et al (37% and 38% of patients with CPO <3 hours,8 19) and by Reichlin et al (222 patients with CPO <3 hours out of 718, ie, 31%).20 More recently, Stallone et al reported 519 (26%) patients that arrived within 2 hours of symptom onset to the ED,6 and Twerenbold et al reported the largest subgroup investigated so far with 1322 early presenters (with CPO <3 hours) out of 4368, that is, 30%.21 This may reflect that our study was performed in large urban areas equipped with prehospital emergency ambulances. A more prolonged delay might be expected in more rural regions. The exact definition of very early presenters is still a matter of debate. Authors nevertheless agree to define them as presenting before 2 hours.20 Very few studies examined the specific groups of early/very early presenters4 6 8 20 In the ESC guidelines, a different strategy is recommended for patients with versus without CPO <6 hours (0/3 hours algorithm).1 Earlier presenters are taken into account in the 0/1-hour algorithm, but in this strategy the rapid exclusion with a unique measurement at admission (H0) is only applicable if CPO >3 hours.1 We believe that this proportion is not negligible and the impact of this very early population might be underestimated in studies were the CPO is not evaluated.

We observed that AUCs of cTnI, cTnI +copeptin and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (HS-cTnT) were significantly lower when CPO <4 hours. The NPVs were not significantly impacted by the CPO, but a suboptimal sensitivity and a non-negligible proportion of misclassified NSTEMI was observed in patients with CPO <2 hours for all tested thresholds and combinations, even if cTnI and HS-cTnT performances can be improved by using a lower threshold for positivity or adding copeptin. The same was true for patients with CPO 2–4 hours, except when using the combination of HS-cTnT <5 ng/L and copeptin <12 µmol/L. We reported the number of misclassified patients in addition to sensitivity and NPV, because NPV is known to be dependent of the prevalence, thus its value might be biased. The absolute number of misdiagnosed patients might be more clinically pertinent than NPV.22

As previously suggested,1 we found that sensitivity and NPV of a single measurement of HS-cTn at admission seems not safe enough to exclude an NSTEMI in very early presenters. We here show that lowering HS-cTn decisional threshold to LoD or to LoB is not sufficient to detect all NSTEMI among very early chest pain presenters. Although combining copeptin to HS-cTnT increased sensitivity and lowered number of misclassified patients, none of the tested strategies allowed for identification of all NSTEMI. Results obtained in very early presenters were very similar to patients with CPO 2–4 hours, except that in this later subgroup combining copeptin with HS-cTnT succeeded in significantly increasing sensitivity (all NSTEMI patients had a detectable HS-cTnT and/or an elevated copeptin).

Our results can be compared with those of Boeddinghaus et al who found that sensitivity of a single HS-cTn measurement is lower in very early presenters, in comparison to all patients.4 These authors indicated that using a single cut-off approach, 61% of the very early presenters were ruled out, which resulted in a sensitivity of 94% and an NPV of 98%. They conclude that the single cut-off strategy should not be applied in early presenters. However, the authors did not evaluate the impact of copeptin across CPO categories. In another study, the same authors indicated that the additional use of copeptin did not sufficiently improve diagnostic accuracy in early presenters.23 Here again, our results are in accordance with those of Boeddinghaus et al indicating that copeptin did not improve diagnostic accuracy of hs-cTnI at presentation in early presenters.23 Mueller et al showed, using the rapid 0/1-hour algorithm that 63% patients with CPO <6 hours were classified as rule out. However, seven patients were missed (0.9% rate), in whom three had HS-cTnT <LoD at presentation and at 1 hour.2 Moreover, a single cut-off value for HS-cTnT at 14 ng/L at presentation resulted in a sensitivity of 88.7% and an NPV of 97.3%, and performed less adequately than the combination of HS-cTnT at presentation with 1-hour level and 1-hour absolute change.2 In a more recent study, Mokhtari et al evaluated a rapid 0/1-hour protocol for discharge chest pain patients based on a single value less than LoD at admission.24 These authors found two missed patients in their population, and recognise that the safety of such rapid protocol is not clear in very early presenters. They further recommend additional HS-cTnT testing at 3 hours for very early presenters.24

Performance of cTns, although measured using HS assays, might be limited in very early presenters because of their kinetics of release into the blood circulation.8 The release of cTn into the circulation following cardiomyocyte damage is a time-dependent phenomenon,25 and a single measurement approach may fail at identifying AMI very early after the onset of symptoms.26 Indeed we, like other authors, found very early presenters with undetectable HS-cTnT at admission. Time-dependent release of copeptin during AMI has been described earlier, and this biomarker has been considered as an early biomarker.8 Copeptin increases immediately after induction of ischaemia, and peaks 90 min after.27 However, some authors recently indicated that copeptin kinetics might be different in NSTEMI in comparison to STEMI, and that if copeptin is increased at first medical contact in the ambulance, the circulating concentrations may rapidly decrease down to normal ranges at the time of hospital admission.28 Our results are in accordance with this observation, as we found one misdiagnosed NSTEMI very early presenter with non-elevated copeptin.

Lastly, our results are reinforced by those of Stallone et al who found that the additional use of copeptin did not increase diagnostic accuracy in very early presenters.6 Furthermore, the NPV for the combination of HS-cTnT and copeptin was lower in patients arriving in the first 2 hours than in those arriving after 2 hours.6 However, these authors did not evaluate the LoD nor LoB of HS-cTnT in their work. We here report that even when lowering the cut-off of HS-cTnT, the combination of HS-cTnT and copeptin seems not enough to detect all NSTEMI among all very early presenters. Our study and the one of Stallone et al 6 are in accordance with previous studies that have shown that there is no or marginal benefit when adding copeptin to HS-cTn assays; indeed, Wildi et al indicated that copeptin provides no significant increase in AUC when combined to HS-cTn,29 either in their all population or in patients with CPO <4 hours. These authors found an incremental value in sensitivities, NPV and calculating the integrated discrimination improvement index, but they did not evaluate low HS-cTn thresholds such as LoB and LoD values.29

Of note, all patients with CPO >4 hours had detectable cTnI and HS-cTnT, that is, the use of copeptin in this situation added no gain. Other studies reported that copeptin testing for the rule out of NSTEMI should be limited to CPO <6 hours.1 13 According to our data, the added value of copeptin might be more restricted, but further studies are needed to confirm our findings.

The current ESC guidelines incorporate an additional criterion for direct rule out of patients that are not very early presenters; indeed, the rapid rule out using a single measurement at admission is possible only if CPO is >3 hours.1 Furthermore, this rapid algorithm can be used only for 3 HS-cTn assays, including HS-cTnT. Considering our data about patients with CPO >4 hours, we note that our conclusions are in line with the recommendations. Therefore, the use of a single measurement at admission might be used for a safe rule out in patients that are not very early presenters. The alternative rule out criteria, combining baseline concentration and 1-hour change, should be used in early presenters.

Limitations of our study

First, it is a post hoc analysis of three previously published studies, and some data are missing (vital signs at admission, details in ECG findings, eg). Second, only a single measurement of troponin at admission was considered for this analysis, and we did not evaluate its kinetics; we, therefore, cannot comment on the accuracy of the recent 1-hour algorithm in our population.1 2 Third, different cTn assays were used across the different centres11–13 and we had to normalise cTnI values before analysis in order to minimise bias. However, all centres evaluated the same HS-cTnT and copeptin. Fourth, as the gold-standard diagnosis was based on a non-HS cTn, we recognise that this could result in underdiagnosis of myocardial injury. Previous studies have shown that an early rule out of NSTEMI using Hs-cTn alone, also in the vulnerable subgroup of early presenters, is safe (with high AUC, sensitivities and NPV in patients presenting with CPO <3 hours).20 In our study, the combined biomarkers are not safe enough for early rule out of NSTEMI in patients presenting very early (CPO <2 hours). The fact that gold-standard diagnoses were adjudicated by the use of a conventional but not a Hs-cTn assay, and that different assays where used, may have led to underdiagnose patients. This point limits the generalisability of our findings and explains why sensitivities and NPVs were much lower as compared with previous studies. However, our results are comparable to those of Stallone et al how recently used an HS-cTn, as suggested by our AUC (0.85 (95% CI 0.79 to 0.90)) in comparison to those of Stallone (0.86 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.090)).6 However, the aim of our work is not to evaluate another time global HS-cTn accuracy, but to highlight CPO effects on diagnostic accuracy of HS-cTn combined or not to copeptin. Fifth, we examined three subgroups with CPO <2 hours, 2–4 hours and 4 hours and defined very early presenters as those having CPO <2 hours, as based on the accepted definition of early presenters.20 Even if very early presenters represent more than one-third of the studied population, the number of very early presenters (CPO <2 hours) is relatively small, although data from three cohorts were used. This explains why false rule out of three patients results in a significant drop in sensitivity and NPV. Many previous studies investigated the rule out performance in early presenters using, for example, the LoD of Hs-cTnT and Hs-cTnI and found much higher sensitivities and NPVs. This can be explained due to a larger number of patients.4 20

Conclusion

A single measurement of HS-cTnT alone or in combination with copeptin at admission seems not sensitive enough to safely rule out NSTEMI in very early presenters (CPO <2 hours from ED admission). If other studies confirm our findings, another strategy to safely exclude NSTEMI in this specific population that represents one-third of patients with chest pain is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: PR, CM, MS and NP contributed to the design and inclusions. CC-G, SL, A-MD and GL realised sample collections and biomarker measurements. CC-G and PR realised statistical analysis. All authors approved the final manuscript. ThermoFisher Scientific and Roche Diagnostic provided reagents.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: CC-G, PR and CM received honorarias and lecture fees from Roche Diagnostics andThermofisher Scientific.

Ethics approval: All studies received approval from local institutional review board. The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at with the doi: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.8t87571.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 20162016;37:267–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mueller C, Giannitsis E, Christ M, et al. Multicenter Evaluation of a 0-Hour/1-Hour Algorithm in the Diagnosis of Myocardial Infarction With High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T. Ann Emerg Med 2016;68:76–87. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wildi K, Nelles B, Twerenbold R, et al. Safety and efficacy of the 0 h/3 h protocol for rapid rule out of myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2016;181:16–25. 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boeddinghaus J, Nestelberger T, Twerenbold R, et al. Direct Comparison of 4 Very Early Rule-Out Strategies for Acute Myocardial Infarction Using High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin I. Circulation 2017;135:1597–611. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pickering JW, Than MP, Cullen L, et al. Rapid Rule-out of Acute Myocardial Infarction With a Single High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T Measurement Below the Limit of Detection: A Collaborative Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:715–24. 10.7326/M16-2562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stallone F, Schoenenberger AW, Puelacher C, et al. Incremental value of copeptin in suspected acute myocardial infarction very early after symptom onset. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2016;5:407–15. 10.1177/2048872616641289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chenevier-Gobeaux C, Lefevre G, Bonnefoy-Cudraz E, et al. Why a new algorithm using high-sensitivity cardiac troponins for the rapid rule-out of NSTEMI is not adapted to routine practice. Clin Chem Lab Med 2016;54:e279–80. 10.1515/cclm-2016-0015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Keller T, Tzikas S, Zeller T, et al. Copeptin improves early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2096–106. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Stelzig C, et al. Incremental value of copeptin for rapid rule out of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:60–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lipinski MJ, Escárcega RO, D’Ascenzo F, et al. A systematic review and collaborative meta-analysis to determine the incremental value of copeptin for rapid rule-out of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:1581–91. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.01.436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raskovalova T, Twerenbold R, Collinson PO, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of combined cardiac troponin and copeptin assessment for early rule-out of myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2014;3:18–27. 10.1177/2048872613514015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chenevier-Gobeaux C, Freund Y, Claessens YE, et al. Copeptin for rapid rule out of acute myocardial infarction in emergency department. Int J Cardiol 2013;166:198–204. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Möckel M, Searle J, Hamm C, et al. Early discharge using single cardiac troponin and copeptin testing in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome (ACS): a randomized, controlled clinical process study. Eur Heart J 2015;36:369–76. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sebbane M, Lefebvre S, Kuster N, et al. Early rule out of acute myocardial infarction in ED patients: value of combined high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T and ultrasensitive copeptin assays at admission. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:1302–8. 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chenevier-Gobeaux C, Meune C, Lefevre G, et al. A single value of high-sensitive troponin T below the limit of detection is not enough for ruling out non ST elevation myocardial infarction in the emergency department. Clin Biochem 2016;49:1113–7. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:W1–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00012-w1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32:2999–3054. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2012;126:2020–35. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826e1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keller T, Zeller T, Ojeda F, et al. Serial changes in highly sensitive troponin I assay and early diagnosis of myocardial infarction. JAMA 2011;306:2684–93. 10.1001/jama.2011.1896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med 2009;361:858–67. 10.1056/NEJMoa0900428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Twerenbold R, Neumann JT, Sörensen NA, et al. Prospective Validation of the 0/1-h Algorithm for Early Diagnosis of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:620–32. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Righini M, Aujesky D, Roy PM, et al. Clinical usefulness of D-dimer depending on clinical probability and cutoff value in outpatients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:2483–7. 10.1001/archinte.164.22.2483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boeddinghaus J, Reichlin T, Nestelberger T, et al. Early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in patients with mild elevations of cardiac troponin. Clin Res Cardiol 2017;106:457–67. 10.1007/s00392-016-1075-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mokhtari A, Lindahl B, Schiopu A, et al. A 0-Hour/1-Hour Protocol for Safe, Early Discharge of Chest Pain Patients. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:983–92. 10.1111/acem.13224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. White HD. Pathobiology of troponin elevations: do elevations occur with myocardial ischemia as well as necrosis? J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:2406–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Korley FK. The Wait for High-Sensitivity Troponin Is Over-Proceed Cautiously. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:112–3. 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gu YL, Voors AA, Zijlstra F, et al. Comparison of the temporal release pattern of copeptin with conventional biomarkers in acute myocardial infarction. Clin Res Cardiol 2011;100:1069–76. 10.1007/s00392-011-0343-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Slagman A, Searle J, Müller C, et al. Temporal release pattern of copeptin and troponin T in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome and spontaneous acute myocardial infarction. Clin Chem 2015;61:1273–82. 10.1373/clinchem.2015.240580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wildi K, Zellweger C, Twerenbold R, et al. Incremental value of copeptin to highly sensitive cardiac Troponin I for rapid rule-out of myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2015;190:170–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.