Abstract

Objective

To identify priorities for the delivery of community-based Child and Adolescent Mental health Services (CAMHS).

Design

(1) Qualitative methods to gather public and professional opinions regarding the key principles and components of effective service delivery. (2) Two-round, two-panel adapted Delphi study. The Delphi method was adapted so professionals received additional feedback about the public panel scores. Descriptive statistics were computed. Items rated 8–10 on a scale of importance by ≥80% of both panels were identified as shared priorities.

Setting

Eastern region of England.

Participants

(1) 53 members of the public; 95 professionals from the children’s workforce. (2) Two panels. Public panel: round 1,n=23; round 2,n=16. Professional panel: round 1,n=44; round 2,n=33.

Results

51 items met the criterion for between group consensus. Thematic grouping of these items revealed three key findings: the perceived importance of schools in mental health promotion and prevention of mental illness; an emphasis on how specialist mental health services are delivered rather than what is delivered (ie, specific treatments/programmes), and the need to monitor and evaluate service impact against shared outcomes that reflect well-being and function, in addition to the mere absence of mental health symptoms or disorders.

Conclusions

Areas of consensus represent shared priorities for service provision in the East of England. These findings help to operationalise high level plans for service transformation in line with the goals and needs of those using and working in the local system and may be particularly useful for identifying gaps in ongoing transformation efforts. More broadly, the method used here offers a blueprint that could be replicated by other areas to support the ongoing transformation of CAMHS.

Keywords: organisation of health services, community child health, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Provides a method for assessing and developing consensus in relation to regional service delivery priorities whilst ensuring salience of public and patient views.

Comparison of study findings with on the ground service transformation efforts can highlight gaps and next steps for service commissioners.

Over-representation of participants from Cambridgeshire and Peterborough and under-representation of particular professional groups potentially limits regional generalisability and reliability.

The list of service features from which priorities were subsequently generated was based on the input of a self-selecting group of professionals, children, young people and parents, whose views may not be generalisable to stakeholders across the region or other parts of the country.

Introduction

The worldwide-pooled prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents is estimated at 13.4%.1 In the UK one in ten children aged 5–16 years suffer from a diagnosable mental health (MH) condition while many more experience symptoms that, while not reaching the threshold of clinical disorder, are a source of distress for children, young people (CYP) and their families.2 A half of lifetime mental illnesses start by the age of 15 and 74% by the age of 18.3

Despite the high burden of disease attributable to MH difficulties4 there remains a significant treatment gap, where CYP who would benefit from intervention are for myriad reasons, unable to access it.5–8 For example, in the UK only 35% of children with clinically significant MH problems are identified9 and only 25% of children receive specialist care.10

Numerous reviews conclude Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) provide delayed, fragmented and heavily restricted access to support and treatment to a small subgroup of people with severe and complex disorder, in various uncoordinated systems.11–15 These challenges, coupled with an increase in the number of people seeking MH services have led to inadequate provision and worsening outcomes.12

In the UK and elsewhere there is consensus that redesign and transformation of CAMHS is needed. As such, there have been a number of attempts to describe what ‘good looks like’ by setting out key features, principles and targets that should guide innovation. Common objectives are: (1) delivery of universally accessible comprehensive and integrated MH services, (2) an emphasis on promotion of mental well-being and prevention of mental illness, (3) strong multiagency partnerships that extend beyond health, (4) delivery in community-based settings that are convenient for CYP and families, (5) services that are intentionally built around the needs of CYP and families, (6) involvement of members of the public and service users in the design and delivery process and (7) use of evidence-based treatment, and (8) implementation of continual monitoring of quality and safety using shared outcome measures and (9) commitment to workforce development.12 16–19 Many of these principles are captured in the recent report by the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Taskforce ‘Future in Mind’ which sets out a vision for CAMHS in England, to be realised by 2020. The report serves as an architecture for transformation that must be interpreted and operationalised at a local level through the development and implementation of local transformation plans.20 These publicly available plans are developed by local clinical commissioning groups, working closely with health and well-being board partners and with strong input from CYP and those who care for them. This place-based strategy for implementation reflects the notion that to achieve equity of outcomes, differentiated models of service delivery will be required in different places to reflect local need and priorities.15 17 21 22

Nevertheless, identification of local shared goals and priorities to guide such transformation efforts is challenging; the priorities of different groups are not always aligned,23 and in a climate of limited professional, financial and material resources it is not always possible to implement every good idea.24 Therefore, a systematic and accountable process of establishing service delivery priorities is needed to provide a transparent way of allocating scarce resources in a way that reflects local need and views.

Current study

In 2015, the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) East of England Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care undertook a study to inform the transformation of local community-based (ie, those not delivered in specialist inpatient settings) CAMHS. The aim of the study was to use consensus methods to identify components of service provision that were perceived as priorities by members of the public and professionals from the children’s workforce (professionals from different sectors working directly with babies, children or young people or who are working to improve outcomes for children through the commissioning, oversight and delivery of services).

The study was jointly conceived of by the senior author and the chief executive of Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Mental Health Foundation Trust, for the purpose of guiding service redesign against a backdrop of finite resources and fragmentation within the local system. The timing of the study coincided with the publication of national policy setting out a vision for CAMHS,18 and thus there were national and local ‘pulls’ for evidence to inform service improvement.

At the time of undertaking the study, it was estimated that National Health Service and local authority-commissioned service capacity for children with mild to moderate MH need and above would have to double or triple in size to meet estimated levels of prevalence in Cambridgeshire.25 There was no statutory provision of CAMHS for children with mild to moderate problems, no overarching model of treatment, no unified structures providing clinical governance and a lack of shared definitions and outcomes.26 Feedback from parents and children indicated need for better information about MH and well-being, as well as the services available. Parents voiced the need for a comprehensive CAMHS model with better partnership working between agencies, particularly schools and MH services.27

This paper reports the results of a modified Delphi study, focusing on those service features that emerged as shared priorities for service delivery and discusses implications of these findings in the context of ongoing CAMHS transformation.

Method

A two-phase, mixed-method design was employed to (1) gather public and professional opinions regarding the key principles and components of effective and acceptable community-based MH services (phase 1) and (2) assess and develop consensus regarding those components perceived by study participants to be critical for service delivery (phase 2). For reasons of space, the methods and tools for phase 1 of the study are reported in online supplementary appendices 1 and 2.

Design

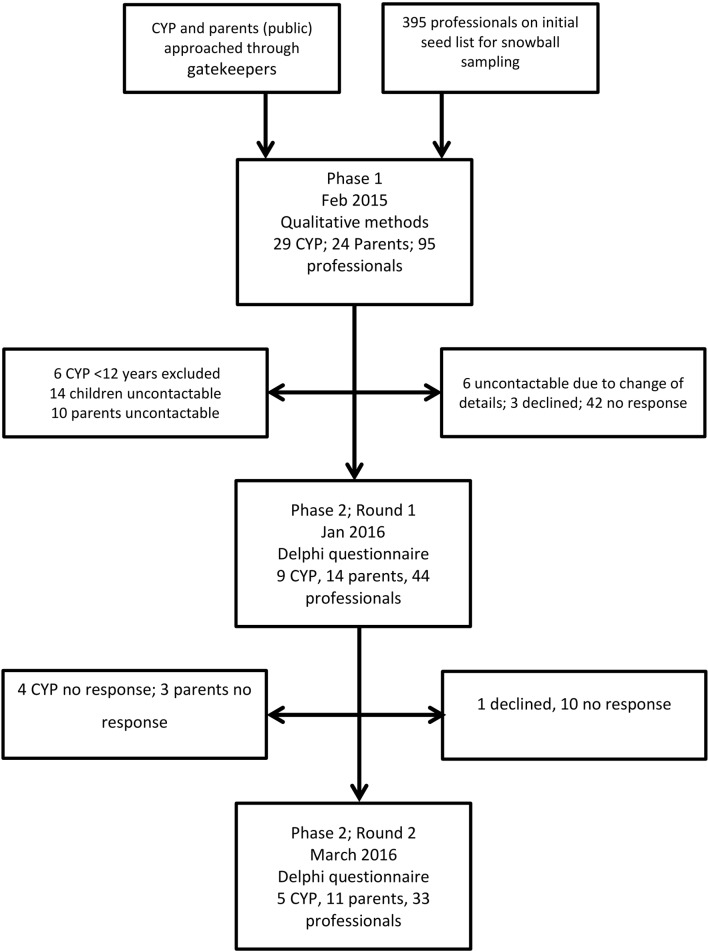

A modified two-round Delphi study (see figure 1) was undertaken with the aim of identifying important components of a regional community-based MH response for CYP. The Delphi technique is an iterative multistage process designed to seek opinion from and develop consensus among a defined group of individuals (panel). The method is frequently used when evidence in an area is known to be limited or contradictory. Key features include (1) an anonymous survey process, whereby a panel (or multiple panels) of experts (by profession and/or experience) use a questionnaire to rate a series of statements over a number of rounds; (2) the provision of structured feedback to panel members between rounds with the ability to adjust ratings in light of knowledge about the group opinion and (3) anonymity for panel members during the process.28 These features can facilitate the convergence of opinion across rounds, helping to build consensus while at the same time highlighting areas of continuing disagreement.

Figure 1.

Overview of Delphi study process. CYP, children and young people.

The method has been used extensively in the context of MH services research.28 With respect to child and adolescent MH the method has been used to identify key ethical issues in relation to the conduct of MH research with minors,29 the development of quality standards for child and adolescent MH in primary care,30 and identification of discredited assessment and treatment methods used with CYP.31 The method has also been used for practical applications—for example, Kelly and colleagues conducted a Delphi study to produce publicly available MH first aid guidelines for suicidal ideation and behaviour.32

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the study reported here is the first to use the method to identify features of community-based MH provision for CYP.

In previous Delphi studies in the area of MH research, participants have mostly been professionals. However, with the acceptance of the necessity to involve service users in the design of all aspects of care, experts by experience are increasingly included in Delphi panels.28 The opinions of different panels can be analysed together or separately in multiple panels.33 However, if different groups with potentially conflicting views are included in a single panel, they may not be equally represented in the final consensus.33

For this reason, the current study included separate public and professional panels to enable exploration of within and across panel consensus. In a further effort to ensure service user views remained central during this priority setting exercise, the Delphi method was adapted so in addition to feedback about their individual and own panel scores for each item, professionals also received feedback about the public panel scores. This adaptation was informed by evidence that feedback of patient scores to clinicians results in an expanded set of consensus items that better reflect the priorities of patients.34 Feedback on professional scores was not given to the public panel, so as to minimise the possibility that members of the public would tailor their answers to agree with a group who may have been perceived as more authoritative.33

Patient and public involvement

The study protocol and materials were reviewed by three young people and one parent prior to seeking ethical approval. All documentation was refined in line with feedback. In developing the Delphi questionnaire, consultation was undertaken with four parents, three young people and three professionals involved with designing, delivering and commissioning MH and emotional health and well-being services for children and young people in the region (see online supplementary appendix 1). Feedback was received regarding missing content (professionals), the need to distinguish between different groups of professionals with respect to some of the questions (professionals), length (parents and young people) and ease of understanding of general and relating to specific concepts (parents and young people). Feedback was used to refine the questionnaires. Representatives of service user and parent/carer fora were invited to and attended two dissemination events.

bmjopen-2018-022936supp001.pdf (318.1KB, pdf)

Participants

The intention was to approach all participants recruited in phase 1 (see figure 1 and table 1) for consent to take part in the Delphi study. However, given the complexity and length of the rating task only members of the public panel aged 12 years and over were invited to take part in the second phase. Six CYP were excluded owing to their age. There was some attrition between study phases and also across the two rounds of the Delphi study, in both panels (see figure 1 and table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics across phases 1 and 2

| Panel | Variable | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | |

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |||

| Public: Children and young people | N | 29 | 9 | 5 |

| Mean age (SD) | 14.09 (7.14) | 16.00 (3.50) | 15.60 (3.36) | |

| Worried about mental health | n/a | 67% | 60% | |

| Access services | n/a | 33% | 40% | |

| Public: Parents | N | 24 | 14 | 11 |

| Age of children (total N) | ||||

| 0–4 years old | 7 | 5 | 5 | |

| 5–10 years old | 11 | 10 | 7 | |

| 11–15 years old | 9 | 9 | 7 | |

| 16–19 years old | 9 | 8 | 6 | |

| 20–24 years old | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 25 and older | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Worried about mental health? | n/a | 86% | 82% | |

| Access to services? | n/a | 71% | 82% | |

| Professionals | N | 95 | 44 | 33 |

| Sector | ||||

| Health | 42 | 26 | 21 | |

| Local authority | 19 | 1 | 1 | |

| Education | 16 | 10 | 8 | |

| Academia | 13 | 9 | 6 | |

| Voluntary sector | 9 | 6 | 5 | |

| Commissioning | 10 | 1 | 1 | |

| Social care | 10 | 1 | 1 | |

| Policing and justice | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Faith | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Role (round 1)* | ||||

| Commissioner | 8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Community group leader | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Counsellor/psychotherapist | 5 | 1 | 1 | |

| Doctor (General Practitioner) | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Doctor (other—please specify below) | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| Head teacher | 6 | 2 | 1 | |

| Manager (clinical) | 5 | 2 | 2 | |

| Manager (strategic) | 14 | 5 | 5 | |

| Manager (other—please specify below) | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mental health worker (please specify below) | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Nursing (primary care) | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Nursing (secondary care) | 3 | 3 | 1 | |

| Nursing (school) | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Psychologist | 5 | 3 | 3 | |

| Researcher | 5 | 4 | 2 | |

| Social worker | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Teacher | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Youth worker | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 29 | 14 | 11 | |

| County† | ||||

| Bedfordshire | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

| Buckinghamshire | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cambridgeshire | 83 | 36 | 27 | |

| Essex | 5 | 1 | 1 | |

| Hertfordshire | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

| Norfolk | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Peterborough | 9 | 7 | 6 | |

| Suffolk | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| Geographic reach‡ | ||||

| Local/county | 79 | 35 | 35 | |

| Regional (several counties) | 28 | 15 | 15 | |

| National (several regions) | 12 | 9 | 9 | |

| International (several countries) | 10 | 6 | 6 | |

*Participants selected more than one role therefore the subtotal may be greater than number of participants in round.

†Participants may have selected more than one county therefore the subtotal may be greater than number of participants in round.

‡Participants may have selected more than one option for reach therefore the subtotal may be greater than number of participants in round.

Delphi questionnaire

In total 181 statements were developed and arranged in four sections corresponding to the key themes identified in phase 1 (see online supplementary appendix 1 and 2 for method and tools, respectively). Questionnaire items varied in their focus from those representing high order values that should underpin service delivery and description of key problem areas, to specific ideas regarding the way services should be targeted, delivered and evaluated. Review by members of the public and professionals involved in MH service delivery lead to a reduction in items, resulting in a questionnaire comprising 137 items for use with the public panel and 173 statements for the professional panel (see online supplementary appendix 3 for all questionnaire statements). The professional questionnaire contained more items due to the inclusion of statements relating to the improvement of professional working practices. Items that were not presented to the public panel can be found in online supplementary appendix 3 under the heading ‘getting services to work better together’).

bmjopen-2018-022936supp003.pdf (615.9KB, pdf)

Completion of the questionnaire required panel members to rate each statement using a ten-point scale to indicate their agreement with a principle or the importance of a service feature (0, low importance/agreement; 10, high importance/agreement). Panellists were invited to give comments at the end of the round 2 questionnaire to justify any of their ratings, or to make suggestions about missing items. As a result, seven additional questions were added to the round 2 questionnaire.

Procedure

An online questionnaire (round 1) was distributed in January 2016 to all professionals who had participated in phase 1 of the study. Given that nearly a year had elapsed since the first round of the study (owing to longer than anticipated to develop and refine the Delphi questionnaire), participants were asked to re-consent to their involvement in the study before being able to access the survey. CYP and parents were contacted by post and email to ensure that they were happy to continue participation in the study. Participants who did not reply within 7 days were sent the questionnaire using the preference stated in round 1. Parents of children aged <12 years were contacted by email and letter to explain that their child would not be required to participate further. A £20 shopping token was included with the letter as a token of appreciation for their child’s participation. Participants received weekly reminders to complete the round 1 questionnaire over the course of 3 weeks. Questionnaire data were downloaded from the online survey platform and uploaded to the study database.

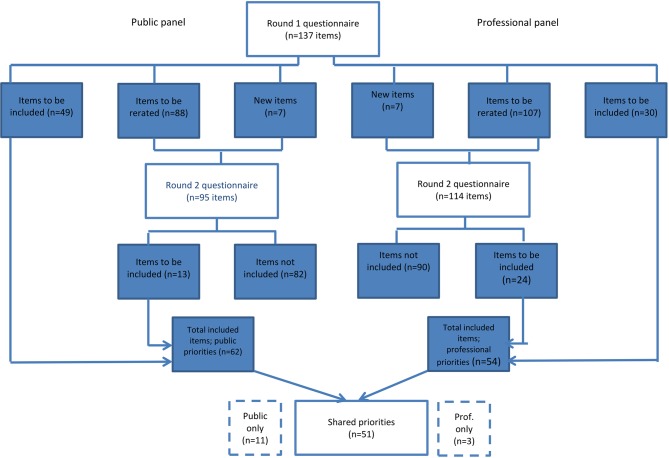

Data from paper questionnaires were manually entered into the study database. Round 1 responses were analysed for each panel. Those items reaching the prespecified criterion for consensus (see figure 2) were removed from the questionnaire. Given analyses for each group were treated separately, the items removed from each questionnaire differed between panels. Individualised questionnaires were prepared for each participant; item level feedback was provided for each of the remaining statements and included an individual’s rating for each item along with the average group rating. In addition professionals were informed of the average public rating for each remaining questionnaire item.

Figure 2.

Flow chart showing the number and outcomes of Delphi items rated by both panels.

Only those participants who had completed round 1 were sent the second questionnaire. As in round 2, non-responders received weekly reminders over a period of 3 weeks. Data were entered into the study database as before and analysed to determine additional items reaching consensus within panels. Work was then undertaken to identify items reaching consensus that were common to both groups (shared priorities).

Analysis

There are a range of methods for defining consensus,35 with no clear recommendation as to which is preferable.33 35 36 For the purpose of this study, consensus regarding important or unimportant items was defined as an item scored as 8–10 or 1–3 by ≥80% of panellists; use of the proportion of participants agreeing within a particular rating range is a common way of defining consensus.35 In a review exploring definitions of consensus, 75% was found to be the median threshold to define consensus.35 although we used a higher proportion in an attempt to separate essential items from those that could be seen as merely desirable. The same criteria were used in round 2 to identify additional items reaching within panel consensus.

To aid interpretation and discussion, items reaching within group consensus in either round were identified for both panels and grouped thematically beneath relevant chapter headings by a single researcher (EH). As a final step, items were identified as shared priorities if they met the threshold for consensus across both groups.

The lack of clear guidance with respect to the definition of consensus means the threshold used in the current study could be viewed as arbitrary and conservative. A sensitivity analysis was undertaken where a lower threshold of 70% was used to examine whether this had a significant impact on the number and type of items emergent as priorities (table displaying all items, whether consensus was reached and in which round is presented as in online supplementary file 2).

bmjopen-2018-022936supp002.pdf (615.9KB, pdf)

Results

The aim of this study was to identify essential components of community-based MH provision, therefore only the results of phase 2—the Delphi study—are reported here.

From table 1 it can be seen that in round 1, composition of the public panel reflected a reasonable spread of CYP age (as indicated by parent reports), concern about MH issues and contact with specialist services. Between rounds, there was a 30% reduction in panel size, resulting in a small decrease in the proportion of panel members reporting current concerns about MH and a more substantial increase in the proportion of CYP and parents reporting that they were currently in contact with specialist health services (not exclusively MH).

With respect to the professional panel, from the outset of phase 2, there was poor representation of local authority and social care professionals, despite involvement in fairly high numbers in phase 1. Across both panels there was an over-representation of participants from Cambridgeshire relative to other counties in the Eastern region.

There was a reduction in both panels by around 25% between rounds, although proportional representation of panel characteristics did not change.

Summary: A total of 144 items (137 initial items+7 additional items added in round 2) were rated by both panels (see figure 2). Of these, 65 items reached the threshold for consensus in at least one of the panels; 51 items were rated as important/unimportant for service delivery by both panels and are termed ‘shared priorities’ in subsequent description and discussion (see table 2).

Shared priorities: Items reaching consensus across panels

Table 2.

Items reaching consensus (80% or more endorsing a score of 1–3 or 8–10) across both panels

| Category | Item | Public | Professional | ||

| Median (IQR) | % agreement | Median (IQR) | % agreement | ||

| Promotion and prevention | |||||

| Access to trusted information and support | Everyone who works with children and families should help to protect children’s mental health (MH) and well-being. | 10 (0.0) | 96* | 10 (2.0) | 85* |

| Access to trusted information and support | Ensure that GPs have information about support that can be offered to young people if they are experiencing any emotional or MH problems. | 10 (1.0) | 96* | 10 (1.0) | 80* |

| Access to trusted information and support | Set up and advertise online resources specifically for professionals working with children that cover issues such as causes and signs of MH problems and how to get help. | 9 (1.3) | 81† | 9 (2) | 88† |

| Access to trusted information and support | Create a symbol that would show that a website giving information about emotional well-being or MH has been checked by experts and can be trusted. | 9 (2.0) | 83* | 10 (1) | 91† |

| The role of schools in promotion and prevention | Pupils’ emotional well-being should be just as important as their academic performance (eg, exam grades). | 10 (2) | 96* | 9 (2) | 88* |

| The role of schools in promotion and prevention | Promote a school culture that makes all pupils feel important. | 10 (2) | 87* | 10 (1) | 85* |

| The role of schools in promotion and prevention | Promote a school culture that makes all pupils feel safe. | 10 (0) | 83* | 10 (1) | 90* |

| The role of schools in promotion and prevention | Being able to participate in a variety of activities and programmes in school builds children’s and young people’s self-esteem and social skills. | 8 (1.3) | 88† | 9 (2) | 93* |

| The role of schools in promotion and prevention | Teach life skills (eg, how to say ‘no’ and how to consider others) in school on a weekly basis. | 9 (2) | 91* | 10 (1.3) | 91† |

| The role of schools/targeting risk groups | Offer support to pupils who are worried about their exams. | 10 (1.5) | 91* | 8 (2) | 80* |

| The role of schools/targeting risk groups | Offer special help to children with special educational needs and disabilities (eg, schools apply for a statement if needed). | 10 (0.5) | 91* | 10 (1) | 88* |

| The role of schools/targeting risk groups | Offer support to pupils when they move from one school to another (including from primary to secondary school). | 9 (2.0) | 83* | 9 (2.3) | 84† |

| Targeting risk groups | Offer extra help to parents whose children are more likely to develop emotional or MH problems (such as parents with MH problems or parents who have problems with drugs or alcohol). | 9 (2) | 87* | 9 (2) | 85* |

| Targeting risk groups | Offer a chance for parents to join a group to learn how to support a child showing early signs of behavioural problems (parenting programmes). | 10 (1.3) | 94† | 10 (1) | 100† |

| Targeting risk groups | Offer an opportunity to parents who do not want to join a group, to learn about parenting in individual support sessions. | 9 (2) | 83* | 9 (1.3) | 88† |

| Targeting risk groups | Offer support for children and young people who have been diagnosed with autism or attention deficit and hyperkinetic disorder to prevent behavioural problems. | 9 (1) | 95* | 9.5 (1.3) | 88† |

| Getting help | |||||

| Access to services and support | There is (not) enough support available to make sure all children, young people and parents get help, no matter how big or small their problems are. | 1 (0) | 81† | 1 (2) | 84* |

| Access to services and support | Offer support to all children who have emotional problems. | 10 (0) | 100* | 10 (1) | 85* |

| Access to services and support | Services should only be provided to CYP aged 0–13. | 2 (2) | 88† | 0 (1) | 91† |

| Access to services and support | Services should only be provided to CYP aged 13–25. | 2 (1.5) | 88† | 1 (1) | 83† |

| Access to services and support | Services should only be provided to CYP aged 18–25. | 2 (2) | 88† | 1 (1) | 84† |

| Access to services and support | Make sure that anyone working with children and young people is able to recognise when a child or young person is showing signs of a MH problem. | 10 (1) | 91* | 9 (2) | 87* |

| Access to services and support | Every school should have someone who is responsible for the MH of pupils, including arranging staff training, finding expert advice and arranging extra help for pupils who need it (making referrals). | 10 (2) | 91† | 8.5 (2) | 84* |

| Access to services and support | Set up a single point of contact for children, young people and families so they can easily get information, advice and support if they are worried about MH. | 9 (2) | 86* | 9 (1.25) | 81† |

| Access to services and support | If a child or a young person is referred to a MH service, give them information about what to expect during the first visit. | 10 (2) | 91* | 10 (2) | 88* |

| Access to services and support | Assign a professional to work with children and young people with complex needs (eg, more than one problem occurring at the same time like MH and substance misuse issues), so that they have someone specific to support them. | 10 (1) | 90* | 9.5 (1.25) | 89* |

| Interaction between service and service users | Children’s MH services should also pay attention to parents’ MH, and help parents find services if they need support. | 8.5 (2) | 100† | 10(2) | 82* |

| Interaction between service and service users | Offer children, young people and their families some self-help strategies to try out if they are on a long waiting list for a MH service. | 10 (1) | 100* | 10 (2) | 80* |

| Interaction between service and service users | Ensure that if a child or a young person is on a long waiting list for a MH service, they receive regular updates about where they are on the list and how quickly they will reach the top. | 10 (0.25) | 90* | 10 (1) | 94† |

| Interaction between service and service users | If a child, young person or a family miss their appointment with a MH professional, try to find out why and try to solve the issue, rather than close their case. | 10 (0.75) | 100* | 10 (2) | 89* |

| Interaction between service and service users | Wherever possible, make sure that a child, young person or a family sees the same person every time they have an appointment. | 10 (1) | 90* | 9 (2) | 97† |

| Interaction between service and service users | Include parents or carers in their child’s MH support and in planning the support. | 10 (2) | 86† | 9 (2) | 81* |

| Interaction between service and service users | Tell children, young people and parents what to do if they want to see a different MH professional, for example, if they do not get on with the person they have been seeing. | 10 (1) | 90* | 9 (1) | 86* |

| Interaction between service and service users | MH professionals should be trained to work with children and young people. | 10 (0) | 95* | 10 (0) | 92* |

| Interaction between service and service users | MH professionals should be trained to offer therapy. | 10 (2) | 91* | 10(1) | 91† |

| Interaction between service and service users | MH professionals should be positive and relaxed. | 10 (0) | 95* | 10(1) | 82* |

| Interaction between service and service users | MH professionals should be open-minded and fair. | 10(1) | 100* | 10(1) | 87* |

| Interaction between service and service users | MH professionals should be trustworthy. | 10 (0) | 100* | 10 (0) | 92* |

| Interaction between service and service users | MH professionals should be trusting and believes in the young person. | 10 (0) | 100* | 10 (0.75) | 92* |

| Interaction between service and service users | MH professionals should be interested in the child’s, young person’s and their family’s opinion on how to best support them. | 10 (0.75) | 95* | 10 (0) | 95* |

| Interaction between service and service users | MH professionals should be reliable—they do what they promise. | 10 (0) | 100* | 10 (0) | 92* |

| Preventing relapse; supporting CYP after diagnosis | Offer a chance to all parents of children and young people with a diagnosed MH problem to learn more about parenting (take part in parenting programmes). | 8 (1) | 81† | 8.5 (2) | 84† |

| Preventing relapse; supporting CYP after diagnosis | Educate children and young people who get help from a MH service on how to stay well in the future. | 10 (1.75) | 91* | 10 (2) | 87* |

| Preventing relapse; supporting CYP after diagnosis | Create groups where parents and carers supporting children with MH problems are able to talk about their experiences with other parents and carers in a similar situation. | 9 (2) | 86† | 9 (2) | 84† |

| Preventing relapse; supporting CYP after diagnosis | Have schools work together with MH services, to help children who have a MH problem to learn how to take care of themselves. | 9.5 (1) | 82* | 9.5 (1) | 94† |

| Measuring success | |||||

| Service user satisfaction with the care and support received. | 10(2) | 83* | 9 (2) | 88† | |

| Signs of psychological well-being (feelings of independence and autonomy, ability to manage own emotions). | 9 (1) | 100† | 9 (2) | 80* | |

| Signs of social well-being (ability to form and maintain positive relationships with others). | 10 (1.5) | 91* | 9 (2) | 97† | |

| Signs of emotional well-being (feelings of happiness and confidence). | 9 (2) | 91* | 9 (1.25) | 97† | |

| Functioning at school (attendance, attainment). | 10(1) | 91* | 9 (2) | 80* | |

| Symptoms of emotional and mental ill health (eg, specific signs of depression or anxiety). | 10(2) | 91* | 9 (2) | 83* | |

*Denotes that consensus is reached in round 1.

†Denotes that consensus is reached in round 2.

CYP, children and young people; MH, mental health.

Promotion and prevention

Sixteen items (28% of all items in this category) relating to ‘promotion and prevention’ emerged as shared priorities. Items coalesced into three subthemes: accessing trusted information, the role of schools and the proactive targeting of known risk groups and risky developmental periods for intervention.

The most prominent of these themes was the role of schools in promoting emotional health and well-being and preventing mental ill health through a combination of whole school initiatives (eg, building a health promoting culture), the delivery of universal programmes to build resilience and the provision of more targeted support. With respect to identification of specific groups to receive intervention, public and professionals endorsed the proactive identification of groups known to have a higher risk of developing MH difficulties: those facing stressful life events or transitions, and CYP showing prodromal symptoms of behavioural problems. Participants endorsed the delivery of interventions directly to CYP and parents in attempt to mitigate negative child outcomes.

Three priorities related to increasing access to high quality information, with two of these specifically citing the need for information that can be accessed by professionals who may be well positioned to identify early indications of MH difficulties.

Getting help

Twenty-nine items (39% of all items in this category) relating to the theme of ‘getting help’ reached consensus across both panels. Items were grouped into three key themes: accessing services and support, service user experience and strategies to prevent relapse.

In relation to access, both panels endorsed wanting CYP with any degree of difficulty to be able to benefit from formal support, while at the same time acknowledging there is currently insufficient resource available to achieve this. In terms of practical strategies to enhance access to services, participants endorsed that all members of the children’s workforce should be able to identify CYP experiencing MH difficulties, and that schools should establish MH leads who take responsibility for co-ordinating efforts within the school and access to outside agencies. Both panels endorsed the importance of a single point of access to enable easy access to information and supportive services, and the role of a key worker or advocate to co-ordinate service access and navigation for CYP with complex needs.

Fourteen items related to the quality of interaction between specialist MH services and service users across the episode of care, highlighting specific actions such as providing information about position on the waiting list, offer of self-help strategies to use while waiting and proactive follow-up of those CYP and families who miss appointments, as well as the personal attributes of those delivering care. The remaining items related to specific strategies involving CYP, parents or schools for preventing relapse and enhancing resilience following the receipt of specialist MH support.

Measuring success

Six of twelve process and outcome indicators were endorsed as suitable measures for monitoring and comparing the success of all services working within a system to enhance CYP MH.

Items reaching consensus in one panel only

Transforming services; working together

As noted above, items relating to the process of transforming services and enhancement of interagency working were rated by professionals only. In this category four of a possible 17 items were rated as important by at least 80% of the professional panel (see table 3). The overarching theme was ‘sharing’ both at strategic (eg, development of a shared vision) and operational (eg, shared training events, ensuring school-based counselling services worked hand-in-hand with community MH) levels.

Table 3.

Items reaching consensus in one panel only

| Category | Item | Public panel | Professional panel | ||

| Median (IQR) | % | Median (IQR) | % | ||

| Promotion and prevention | |||||

| Access to trusted information and support | Children, young people and their parents trust information about emotional well-being and healthy living that they receive from other (than GPs) health professionals (eg, paediatricians, nurses, mental health workers). | 8.5 (1.8) | 82* | 8 (1.0) | 75 |

| Access to trusted information and support | Children, young people and their parents trust information about emotional well-being and healthy living that they receive from websites (eg, mental health charities, National Health Service). | 8 (0.3) | 81† | 7.5 (1.3) | 44 |

| Access to trusted information and support | Create a website that explains causes and signs of mental health problems, and how to get help. | 8 (1.5) | 75 | 9 (2) | 88† |

| The role of schools in promotion and prevention | Schools can reduce bullying on the internet during the school day by not allowing pupils to use mobile phones and other personal electronic devices (tablets, iPods, personal computers). | 8 (2) | 81† | 8 (2.2) | 50 |

| Getting help | |||||

| Access to services and support | Services should be based on need and not on some arbitrary criteria, such as age: someone might be 20 but feel like 16. Instead, the move to adult services should be flexible, depending on the person. | 9 (2) | 81† | 8.5 (4) | 59 |

| Access to services and support | Young people and parents who are confident in themselves find it easier to get the help they need to deal with their problems. | 9 (2) | 81† | 8 (1) | 72 |

| Access to services and support | If a young person is sure that what they say to a GP will not be told to their family, they are more likely to trust the GP and openly talk about their worries. | 8 (2) | 81* | 8 (2) | 56 |

| Access to services and support | Mental health services should allow parents and children to go to them directly (also called self-referral). If people have to wait for a referral from a GP or another professional, their problems might continue to get worse while they wait. | 8 (1.75) | 82* | 7 (2) | 41 |

| Access to services and support | Teach professionals to first help children and young people to decide what kind of support they need, and then to help children and young people to find that support. | 8 (1) | 69 | 8 (1.25) | 81† |

| Access to services and support | Set up a mental health advice service that children, young people and parents can access 24 hours a day. | 10 (1.75) | 86* | 9 (2.25) | 72 |

| Access to services and support | Offer counselling or talking therapies to all children and young people if there is a chance they could benefit from it, regardless of how big or small their problems are. | 10 (1.75) | 82* | 8 (3) | 59 |

| Preventing relapse; supporting CYP after diagnosis | Organise groups where children and young people experiencing mental health problems can meet and talk to other children and young people in a similar situation. | 9 (1) | 81† | 8 (2.25) | 78 |

| Preventing relapse; supporting CYP after diagnosis | Have mental health services keep in contact with children and families to support them after they have overcome a crisis. | 9 (2) | 90* | 8 (1.25) | 63 |

| Measuring success | |||||

| Knowledge about mental health problems. | 8 (1.5) | 75 | 9 (1.25) | 88† | |

| Transforming services; working together* | |||||

| Transparent strategy | We need to have a clear overview of levels of investment made into children’s mental health across all agencies. | - | - | 8 (2) | 88† |

| Transparent strategy | The outcomes measured by services working with children, young people and their families should be closely linked to a local plan for mental health services, which has been agreed by all relevant agencies. | - | - | 8 (1.5) | 84† |

| Communication and co-ordination | Establish a shared vision between decision makers and professionals of all levels with respect to the design and delivery of effective services. | - | - | 8 (1.25) | 81† |

| Communication and co-ordination | Having a shared set of outcomes that all services measure (as a minimum standard) would help services to work together more effectively, because it creates a sense of joint ownership. | - | - | 8 (1.25) | 81† |

| Communication and co-ordination | For services to work together more efficiently, it is essential that they share information about children, young people and families in their care. | - | - | 8 (1.5) | 81† |

| Communication and co-ordination | If there was a named point of contact in mental health services for schools, it would improve the communication between services, and it would improve referral accuracy. | - | - | 8 (1) | 85* |

| Communication and co-ordination | Ensure that school-based counselling services work together with mental health services. | - | - | 10(1) | 94† |

| Implementation | Speed up the processes of making changes—too many good ideas get stuck in the decision making pipeline. | - | - | 8 (2) | 81† |

*Indicates in which panel and round consensus was reached.

†Note these items were only rated by the professional panel.

CYP, children and young people.

A further 14 items rated by both panels reached consensus in one panel only (professionals, n=3; public, n=11, see table 3). In general, the items represented similar themes to those described above, although mostly reflect aspects of service delivery considered important by the public but relatively less so by professionals.

Sensitivity analysis

When the threshold for consensus was set at 70%, an additional nine items emerged as public priorities and 23 items as professional priorities (see full results table presented in online supplementary file 2). Of these items, five reached consensus across both panels. In relation to ‘getting support’ both panels endorsed the provision of services to CYP aged 0–25 years. In order to increase access, both panels agreed that CYP should be able to choose settings in which to receive services, that MH professionals should be located in non-specialist settings that are frequently accessed by CYP and families, and that MH support should incorporate attention to the social needs of CYP and families. In relation to measuring success, both panels endorsed the number of CYP diagnosed with an MH problem as an important indicator to be measured by all services working with CYP and their families.

Discussion

This study identifies features of comprehensive community-based mental services for children and young people that are important to those who may use (public) and deliver services (professionals). Areas of consensus represent shared priorities for service provision in the East of England.

Three key findings emerged from this study. (1) Priorities relating to the prevention of MH difficulties and the promotion of good MH emphasise the role of education. (2) Priorities relating to the delivery of treatment and support to children and young people experiencing MH difficulties place greater emphasis on the way in which care is delivered and the qualities of those delivering care, than on specific types of intervention that should be available. (3) Outcomes for monitoring and evaluating services and support should measure aspects of well-being and functioning, in addition to measurement of distress symptoms.

Members of the public identified additional priorities that were not endorsed by professionals, highlighting the importance of involving CYP and families in the design of services to ensure they are acceptable and effective for those who will use them.

Comparison to other studies

The role of schools in promotion and prevention: In line with a public health approach, participants prioritised the delivery of both universal interventions and more targeted support for CYP at increased risk of poor outcomes. These findings are in keeping with current national and international policy16 37–39 and in large part reflect what is already being delivered on the ground in UK schools.40 41 Several reviews of whole school interventions and universally delivered resilience building programmes indicate effectiveness in primary and secondary schools.42–45 Similarly, reviews point to the effectiveness of some targeted interventions on MH outcomes.46–48

However, to date there is extremely limited evidence of the effectiveness of mechanisms to systematically identify CYP who could benefit from these school-based programmes which may limit their impact.49 Further it is worth noting much of the high quality evidence included in these reviews derives from North America, with limited evaluation of the effectiveness of these or similar interventions in the UK. Sporadic and inconsistent implementation of interventions remains a significant challenge for school-based interventions delivered in UK settings50–52 which may erode the impact of even highly effective programmes.53 Effort needs to be expended, not only on implementing these approaches in UK schools, but also on evaluating the outcomes that can be achieved for particular groups and in particular settings using pragmatic, transparent and contextually sensitive study designs.54

Accessing support and treatment: It was striking that priorities relating to the delivery of support to those experiencing MH difficulties largely focused on the process through which treatment is accessed and delivered, rather than on the availability of specific therapeutic models of care. With respect to access there was strong disagreement with the practice of rationing services by prioritising delivery to particular age groups as has been implemented in some parts of the UK and elsewhere, which is in line with movement in the UK towards the provision of child and youth services from 0 to 25 years14 55 Participants also endorsed a single point of access model whereby all levels and types of information and support can be accessed through ‘one front door’, and a navigator or advocacy model to help mobilise needed resources for those with complex needs. Results of quantitative studies suggest that enabling self-referral to support via community-based ‘walk in’ services can improve access to care for those who are otherwise discouraged by complicated referral procedures and long waiting lists.13 Similarly, care management where staff provide education, advocacy and logistical support to help patients navigate through the healthcare system (rather than deliver direct support) appears to be a promising approach for improving medical care for adults with severe mental illness treated in community MH settings.56 Nevertheless, while both models are currently promoted and implemented in the UK as ways of increasing access to adult services, there is limited evaluation of their impact on the quality of service provision for CYP.

Measuring success: In line with other studies, concepts of a successful outcome included, but extended beyond measurement of signs and symptoms of MH difficulties, to the quality of children and young people’s relationships, their ability to participate and contribute in their everyday lives and to enjoy and achieve at school.57–59 In order for there to be an incentive to conduct outcome measurement and for the evidence that it yields to be useful, it is imperative that what is measured reflects stakeholder perspectives on what constitutes a good outcome. To this end, the outcomes identified by this study could form the basis of a regional shared measurement system that could be used by all sectors to assess impact of services aiming to improve the health and well-being of CYP. That said, to date there has been a great deal of attention in the UK on the value of routine outcomes monitoring as a key foundation of service transformation21 60 nevertheless, this has largely been confined to clinical settings, with limited spread to other community-based service delivery partners (eg, the voluntary sector) that play a critical role in delivering a comprehensive MH response. Simple measures embedded in frontline practice of all sectors contributing to a public MH response ‘can offer real time feedback to service staff and users and support accountability for sharing in decisions, care planning, and coproduction and coordination of care’ as well as indications of service success and failure.21

Divergence of priorities: In general, there was good agreement between public and professionals; however we identified a subset of service features that were highly valued by members of the public but relatively less so by professionals. This finding concurs with the current strong emphasis on involving CYP and families in the design of services to ensure they are acceptable and effective for those who will use them. Areas of disagreement predominately related to strategies to enhance access to services, which included the ability to access services irrespective of symptom severity, the ability to self-refer to services, 24 hours access and a period of ongoing contact following discharge in case of need for re-admittance. This divergence in views may represent professional awareness of fiscal constraints that prohibit access to specialist services for the many, and perhaps also the view that greater provision of and access to specialised health services can lead to an over reliance on high cost services and products, and an underutilisation of effective primary healthcare and social services that may have a greater effect on health and well-being of the public21 Nevertheless, if these service features are seen as critical by the public then thought must be given to how these might be achieved through the pooling of resources and involvement of professionals from the wider children’s workforce, rather than an over reliance on specialist sector workers.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to use the Delphi method to identify features of a comprehensive community-based MH response for CYP. The adapted method presented here represents a way of assessing and developing consensus in relation to regional service delivery priorities that could be replicated in other areas.

Concerted efforts were made to recruit large and diverse panels. Despite this, the sample was characterised by an over-representation of participants from Cambridgeshire and Peterborough and an under-representation of particular professional groups. The lengthy delay of nearly a year between the first and second phases of the study likely gave rise to significant attrition across rounds. We observed particular gaps in relation to professionals working for the local authority, criminal justice and faith groups, meaning that the priorities identified here may not reflect the views of these sectors of the workforce. Moreover the number of public panel members was rather small by round 3 potentially undermining the reliability of findings; a change of vote by one individual could have had a major effect on whether the agreement criterion was reached.

Also to be considered is that the long list of ideas from which priorities were subsequently generated was based on the input of a self-selecting group of professionals, CYP and parents, meaning that the items generated from their ideas and the prioritisation of service features may not be generalisable to stakeholders across the region. It is also the case that the initial long list of service features may not have been reflective of all necessary aspects of CAMHS service delivery, for example, there were few items that related specifically to service delivery for very young children. That said, the intention was not to produce a comprehensive service specification, rather it was to highlight aspects of delivery that were of particular importance to the public and professionals that could be included in a service specification or transformation plan.

Practical implications

This study sets out a process whereby in the context of sometimes differing or opposing stakeholder opinion and a sea of good ideas, agreement can be reached regarding important elements of CAMHS. This evidence, even in the context of ongoing service transformation, can be used to inform service improvement work in local areas by cross referencing actual activity with the consensus findings.

In comparing the priorities identified by this study with service transformation efforts undertaken in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, as documented in publicly available local transformation plans, there is much overlap between these findings and activity on the ground (perhaps in small part due to the dissemination of findings to local transformation leads). However, some gaps are also evident. For example, several priorities related to address of school culture as a way of promoting good MH. Yet to date, there is little focus on aspects of school life that do not directly relate to the provision of MH training or support, but which contribute to a ‘mentally healthy environment’.61 The Education Policy Institute advocate that all schools, colleges and Universities adopt the WHO recommended Whole School Approach model and thought could be given to how this might be incorporated into subsequent transformation plans.44 61

Similarly, according to the most recent transformation plan, evidence-based parenting programmes have been proactively offered to parents of children waiting to access attention deficit and hyperkinetic disorder and ASD services. While this study highlighted this group of parents as priority recipients, findings also underscore the perceived importance of proactive in-reach to other vulnerable groups such as parents with MH difficulties. Based on review of local transformation plans (LTPs), there is yet to be such explicit targeting of other groups of parents.

Finally, results highlighted the value of offering information to CYP and families when accessing and waiting for specialist MH services, however to date there is little focus on these process aspects of service delivery, with greater emphasis placed instead on the specific services to be offered. Thus, even in the context of significant activity to improve services, the findings from this study produce unique insights that can be used to inform future work.

Conclusion

In a climate of limited professional, financial and material resources, priority setting is a matter of daily concern in healthcare and policy-making. A systematic and accountable process of establishing service delivery priorities, which incorporates the views of relevant stakeholders, can provide a transparent way of allocating scare resources more equitably, in a way that reflects local need.

The areas of consensus identified in this study represent shared priorities for service provision in the East of England, and help to operationalise high-level plans for service transformation in line with the goals and needs of those using and working in the local system.17 22 More broadly, the method described here offers a useful blueprint that can be replicated by other localities to inform ongoing transformation of CAMHS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank members of the public patient involvement group who provided comment on all study materials. The authors are also grateful to Dr Margaret Murphy and Mr Lee Miller who helped to refine the statements included in the Delphi questionnaire. Thanks are extended to Professor Claire Goodman and Dr Isabel Clare for their advice on study design and write-up, respectively. Finally, the authors extend their thanks to the three reviewers whose insightful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript have greatly improved this paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: PBJ and AH conceived of the study. EH was responsible for study design, development of study materials, study conduct and write-up of the manuscript. MV was responsible for data collection and management, development of the Delphi questionnaire and analysis of quantitative data. CL, MV, ANH and EH undertook analysis of qualitative data. EH, MV, CL, AH, ANH and JKA contributed to interpretation of the data and write-up of the manuscript for publication.

Funding: This is a summary of independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care East of England Programme. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study received ethical approval from the Health Research Authority in December 2014, and commenced in February 2015 (14/SC/1371).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Anonymised qualitative and quantitative data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, et al. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2015;56:345–65. 10.1111/jcpp.12381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Green H, Mcginnity A, Meltzer H, et al. Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004. 2005. https://sp.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/5269/mrdoc/pdf/5269technicalreport.pdf (accessed 16 May 2017).

- 3. Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, et al. Prior Juvenile Diagnoses in Adults With Mental Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:709 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Degenhardt L, et al. The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: an analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS One 2015;10:e0116820 10.1371/journal.pone.0116820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2010;10:113 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gondek D, Edbrooke-Childs J, Velikonja T, et al. Facilitators and barriers to person-centred care in child and young people mental health services: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Psychother 2017;24:870–86. 10.1002/cpp.2052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reardon T, Harvey K, Baranowska M, et al. What do parents perceive are the barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in children and adolescents? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;26:623–47. 10.1007/s00787-016-0930-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, et al. Children’s mental health service use across service sectors. Health Aff 1995;14:147–59. 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ford T, Hamilton H, Goodman R, et al. Service contacts among the children participating in the british child and adolescent mental health surveys. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2005;10:2–9. 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2005.00108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Satcher DUS. U.S. Public Health Service, Report of the Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health: A National Action Agenda. Wasington DC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12. The mental health task force. The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anderson JK, Howarth E, Vainre M, et al. A scoping literature review of service-level barriers for access and engagement with mental health services for children and young people. Child Youth Serv Rev 2017;77:164–76. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.04.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McGorry P, Bates T, Birchwood M. Designing youth mental health services for the 21st century: examples from Australia, Ireland and the UK. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2013;54:s30–s35. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raballo A, Poletti M, McGorry P. Architecture of change: rethinking child and adolescent mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:656–8. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30315-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization. Mental health action plan (2013-2020): WHO, 2013:48 ISBN 978 92 4 150602 1. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stiris PT. A consensus on the improvement of community and primary care services for children, adolescents and their families in Europe, 2016:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Department of Health. Future in mind:Promoting, protecting and improving our children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414024/Childrens_Mental_Health.pdf

- 19. Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health. Guidance for commissioners of child and adolescent mental health services. 2013. http://www.jcpmh.info/wp-content/uploads/jcpmh-camhs-guide.pdf

- 20. NHS England. Transformation plans for children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing: Guidance and support for local areas, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mulley A, Coulter A, Wolpert M, et al. New approaches to measurement and management for high integrity health systems. BMJ 2017;356:j1401 10.1136/bmj.j1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ham C, Alderwick H. Place-based systems of care: a way forward for the NHS in England: King’s Fund, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. The Kings Fund and Public Health England (PHE). Stocktake of local strategic planning arrangements for the prevention of mental health problems Summary report About Public Health England. London: The Kings Fund and Public Health England (PHE), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Knottnerus JA, Tugwell P. Prioritization of health care and research given limited and too limited resources. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;86:1–2. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cambridgeshire County Council, NHS Cambridgeshire. Cambridgeshire joint strategic needs assessment the mental health of children and young people in Cambridgeshire, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gathercole S, Humphrey A, Lea-Cox C, et al. Holistic early intervention for young people in cambridgeshire: cambridge family social enterprise model, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cambridgeshire County Council, Peterborough County Council, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Clinical Commissioning Group. Emotional well being and mental health strategy for children and young people, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jorm AF. Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2015;49:887–97. 10.1177/0004867415600891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hiriscau EI, Stingelin-Giles N, Wasserman D, et al. Identifying Ethical Issues in Mental Health Research with Minors Adolescents: Results of a Delphi Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:489 10.3390/ijerph13050489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sayal K, Amarasinghe M, Robotham S, et al. Quality standards for child and adolescent mental health in primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:51 10.1186/1471-2296-13-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Koocher GP, McMann MR, Stout AO, et al. Discredited assessment and treatment methods used with children and adolescents: a delphi poll. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2015;44:722–9. 10.1080/15374416.2014.895941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kelly CM, Jorm AF, Kitchener BA, et al. Development of mental health first aid guidelines for suicidal ideation and behaviour: a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:17 10.1186/1471-244X-8-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sinha IP, Smyth RL, Williamson PR. Using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials: recommendations for the future based on a systematic review of existing studies. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000393 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Macefield R, Blencowe N, Brookes S, et al. Core outcome set development: the effect of Delphi panel composition and feedback on prioritisation of outcomes. Trials 2013;14:P77 10.1186/1745-6215-14-S1-P77 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, et al. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One 2011;6:e20476 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Department of Health, Department for Education. Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: a Green Paper. 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/664855/Transforming_children_and_young_people_s_mental_health_provision.pdf

- 38. Nice. Review of interventions to identify, prevent, reduce and respond to domestic violence, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Excellence NI for H and C. Social and emotional wellbeing in primary education, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vostanis P, Humphrey N, Fitzgerald N, et al. How do schools promote emotional well‐being among their pupils? Findings from a national scoping survey of mental health provision in English schools. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2013;18:151–7. 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00677.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Department for Education. Supporting Mental Health in Schools and Colleges: Quantitative Survey. 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/634726/Supporting_Mental-Health_survey_report.pdf

- 42. Adi Y, Killoran A, Janmohamed K, et al. ; Systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to promote mental wellbeing in children in primary education. Report 1: Universal approaches: non-violence related outcomes, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Blank L, Baxter S, Goyder L, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of universal interventions which aim to promote emotional and social wellbeing in secondary schools. Interventions 2008:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Langford R, Bonell CP, Jones HE, et al. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD008958 10.1002/14651858.CD008958.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dray J, Bowman J, Campbell E, et al. Systematic review of universal resilience-focused interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health in the school setting. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;56:813–24. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Das JK, Salam RA, Lassi ZS, et al. Interventions for adolescent mental health: an overview of systematic reviews. J Adolesc Health 2016;59:S49–S60. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, et al. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2017;51:30–47. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cheney G, Schlösser A, Nash P, et al. Targeted group-based interventions in schools to promote emotional well-being: a systematic review. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2014;19:412–38. 10.1177/1359104513489565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Anderson J, Humphrey A, Ford T, et al. PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews School-based identification of children and adolescents at-risk of, or currently experiencing poor mental health. A systematic review of acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness. 2016:1–6.

- 50. Evans R, Murphy S, Scourfield J. Implementation of a school-based social and emotional learning intervention: understanding diffusion processes within complex systems. Prev Sci 2015;16:754–64. 10.1007/s11121-015-0552-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pearson M, Chilton R, Wyatt K, Woods HB, et al. Implementing health promotion programmes in schools: a realist systematic review of research and experience in the United Kingdom. Implement Sci 2015;10:2–20. 10.1186/s13012-015-0338-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lendrum A, Humphrey N, Wigelsworth M. Social and emotional aspects of learning (SEAL) for secondary schools: implementation difficulties and their implications for school‐based mental health promotion. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2013;18:158–64. 10.1111/camh.12006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol 2008;41:327–50. 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kessler R, Glasgow RE. A proposal to speed translation of healthcare research into practice. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:637–44. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Humphrey A, Eastwood L, Atkins H, et al. An exemplar of GP commissioning and child and adolescent mental health service partnership. J Integr Care 2016;24:26–37. 10.1108/JICA-08-2015-0033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Compton MT, et al. A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: the Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) study. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:151–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cohn E, Miller LJ, Tickle-Degnen L. Parental hopes for therapy outcomes: children with sensory modulation disorders. Am J Occup Ther 2000;54:36–43. 10.5014/ajot.54.1.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Morris C, Janssens A, Allard A, et al. Informing the NHS Outcomes Framework: evaluating meaningful health outcomes for children with neurodisability using multiple methods including systematic review, qualitative research, Delphi survey and consensus meeting. Health Services and Delivery Research 2014;2:1–224. 10.3310/hsdr02150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Howarth E, Moore THM, Shaw ARG, et al. The effectiveness of targeted interventions for children exposed to domestic violence: measuring success in ways that matter to children, parents and professionals. Child Abus Rev 2015;24:297–310. 10.1002/car.2408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fonagy P, Clark DM. Update on the improving access to psychological therapies programme in england: Commentary on … children and young people’s improving access to psychological therapies. BJPsych Bull 2015;39:248–51. 10.1192/pb.bp.115.052282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Frith E. Children and young people’s mental health: time to deliver. London: Education Policy Institute, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022936supp001.pdf (318.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022936supp003.pdf (615.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022936supp002.pdf (615.9KB, pdf)