Abstract

Objectives

Haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) is a serious threat to public health in China, accounting for almost 90% cases reported globally. Infectious disease prediction may help in disease prevention despite some uncontrollable influence factors. This study conducted a comparison between a hybrid model and two single models in forecasting the monthly incidence of HFRS in China.

Design

Time-series study.

Setting

The People’s Republic of China.

Methods

Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model, generalised regression neural network (GRNN) model and hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model were constructed by R V.3.4.3 software. The monthly reported incidence of HFRS from January 2011 to May 2018 were adopted to evaluate models’ performance. Root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE) and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) were adopted to evaluate these models’ effectiveness. Spatial stratified heterogeneity of the time series was tested by month and another GRNN model was built with a new series.

Results

The monthly incidence of HFRS in the past several years showed a slight downtrend and obvious seasonal variation. A total of four plausible ARIMA models were built and ARIMA(2,1,1) (2,1,1)12 model was selected as the optimal model in HFRS fitting. The smooth factors of the basic GRNN model and the hybrid model were 0.027 and 0.043, respectively. The single ARIMA model was the best in fitting part (MAPE=9.1154, MAE=89.0302, RMSE=138.8356) while the hybrid model was the best in prediction (MAPE=17.8335, MAE=152.3013, RMSE=196.4682). GRNN model was revised by building model with new series and the forecasting performance of revised model (MAPE=17.6095, MAE=163.8000, RMSE=169.4751) was better than original GRNN model (MAPE=19.2029, MAE=177.0356, RMSE=202.1684).

Conclusions

The hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model was better than single ARIMA and basic GRNN model in forecasting monthly incidence of HFRS in China. It could be considered as a decision-making tool in HFRS prevention and control.

Keywords: autoregressive integrated moving average, generalized regression neural network, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, prediction

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The monthly incidence of haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) in China showed an uptrend since January 2018, so it is crucial to predict the development of HFRS and prevent its outbreak.

This study evaluated the performance of autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model and generalised regression neural network (GRNN) model and hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model in forecasting incidence of HFRS in China, the results could give a reference to choose suitable model in HFRS prediction.

The reported data we collected may slightly differ from the actual incidence number since reported data came from monitor, it may not include the person who was infected but not went to test.

Many factors could influence the incidence of HFRS but only time factor in study period was considered in our models, thus data should be updated to maintain the model’s accuracy. Besides, there are lots of prediction models and this study only compared three of them, further comparison is needed to choose the best model for HFRS forecasting.

Spatial stratified heterogeneity should be tested in time series prediction research, applying the prediction model in each spatial is an important way to improve the model’s performance.

Background

Hantavirus is a member of family Bunyaviridae which contains the most important zoonotic pathogens of humans.1 Two categories of hantaviruses are Old World (Asia and Europe) virus that causes haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS), and New World (USA) virus that causes hantavirus pulmonary syndrome.2 3 Hantaviruses are spread through the infected mammals’ urine, faeces and saliva. People can be infected mainly through respiratory tract, alimentary tract and skin/mucus membrane abrasion. The onset symptoms of HFRS are fever, circulatory collapse with hypotension, haemorrhage and acute kidney injury.4 5 The hallmark of HFRS is capillary leak syndrome, which causes oedema and haemorrhage and threatens people’s life.6 7 Cases of HFRS are widely distributed in Eastern Asia, particularly in China, Russia and Korea.8 It is reported that the number of HFRS cases in China accounts for almost 90% of the total cases worldwide.9 10 Some comprehensive control activities such as effective vaccine and rodent elimination have achieved remarkable effects, while the incidence of HFRS is still high owing to some uncontrollable factors.11 12 Thus it is important to forecast the diseases trends and get early warning before disease outbreak

Statistic models such as linear regression, artificial neural network and grey model have been widely used in time series forecasting.13 14 Reliable forecasting plays an important role in infectious diseases control before pandemic or outbreak. Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model is one of the most popular methods in diseases prediction. The principle of ARIMA model contains filtering out the high-frequency noise in the data, detecting local trends based on linear dependence and forecasting the development trends. The limitation of this model is that ARIMA can only analyse the linear part of infectious disease series.15 However, the non-linear part of epidemic data may not be white noise, which means some information may be lost by ARIMA model. To overcome the inherent defect of ARIMA model, an artificial neural network (ANN) model was adopted. ANN is a conceptualised mathematical non-linear classification model inspired by the behaviour of biological networks of neurons.16 17 The generalised regression neural network (GRNN) is a member of ANN family and has unique ability of accelerated learning and greater capability for non-linear fitting. The hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model has both advantages of ARIMA model and GRNN model, it means that both the linear part and non-linear part of time series could be fitted by this hybrid model.

Some researches indicated that the hybrid model had better incidence forecasting performance than single ARIMA model and basic GRNN model in infectious diseases,18 while the best model in predicting the incidence of HFRS in China is still unclear. Besides, some studies had compared the performance of hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model with other models19 despite the comparison between the hybrid model with two single models in HFRS prediction is rare. This study aims to develop a single ARIMA model, a basic GRNN model and a hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model to fit and predict the monthly incidence of HFRS in China. The fitting and forecasting performance of these three models were compared with to determine the best one, which is suggested to be employed in the provision of reference information for HFRS control.

Methods

Data sources

The monthly reported incidence data of HFRS in China from January 2011 to May 2018 were collected from the official website of National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (Ministry of Health). All HFRS cases in mainland China must be reported to the National Health Commission through the infectious disease surveillance system within 24 hours. The data was separated into model building part and model forecasting part. According to some researches, the data from January 2011 to December 2017 were adopted to build model while data from January to May 2018 were used for model verification.

Single ARIMA model

The ARIMA model is usually shown as ARIMA(p,d,q)(P,D,Q)S while the parameters mean non-seasonal and seasonal order of autoregression, the degree of difference and moving average, respectively, the subscript means the length of cyclical pattern. An ARIMA model is developed by time series stationary, parameter estimation and model check.20

Time series stationary is the first requirement for ARIMA model establishment, it means no fluctuation or periodicity over time. The augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) unit-root test could help estimating whether the time series is stationary or not. Log transformation and differences are frequently adopted to stabilise the time series.

The parameter D is the length of seasonal difference and d is the length of trend difference, these two parameters are determined when original series is stable. The parameters of p, q, P and Q are determined by researcher’s personal experience through the autocorrelation function (ACF) graph and partial autocorrelation function (PACF) graph of stationary series. Generally, more than one values may be given to each parameter so that several plausible models could be combined.

Since the best model must have the highest accuracy in disease prediction, some substandard models are excluded. A suitable model must show statistical significance in parameter test and get white noise sequence in residual test. Besides, the best model should have the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) value than other combined models.

Basic GRNN model

The GRNN model is built based on non-linear regression theory. The input layer, pattern layer, summation layer and output layer are involved in the construction of GRNN model.21 Its inherent function is to identify the relationship between each input value and output value. Initially, the original data are divided into training set and test set. The test set can be the last two data or two random data of original series, the rest are adopted as the training set. Smoothing factor is the only parameter of GRNN which means the network could not be affected by human. A series of smoothing factors were tested by a circular programme through MATLAB software. Generally, there are more than one possible value of smoothing factor and the best one must have the lowest root mean square error (RMSE). Finally, all the original data were adopted as input part to predict the future data by the GRNN model which was built with the best smoothing factor.

Hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model

The ARIMA model has advantage in extracting and fitting the linear part of the original time series, while the non-linear information in residual is abandoned. GRNN model is combined thanks to its capacity in data mining, so that the limitation of ARIMA model could be overcome. The hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model is developed to demonstrate if it has the highest accuracy in HFRS incidence prediction.

To develop the hybrid model, the input values are the fitting data of ARIMA model while the output values are actual data. Same with the basic GRNN model, the last two samples or two randomly selected samples of original series are used as testing set and the rest are used as training set to find the best smoothing factor and rebuilt the GRNN model. Finally, the forecasted values of ARIMA model is used as the input data of hybrid model to get the output predictive values.

Model revision

Spatial stratified heterogeneity (SSH) refers to the phenomenon that within strata are more similar than between strata.22 SSH is an unavoidable confounder in global model application, especially in areas with huge region.23 The ‘spatial’ not only refer to geospatial meaning, but also mathematical meaning, such as gender, region and education level. In this study, SSH was tested by month to demonstrate if there were different strata in HFRS incidence series. The prediction model will be built in different strata if SSH test is significant.

Model comparison

The forecasting effects of ARIMA model, GRNN model and hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model are estimated with RMSE, mean absolute error (MAE) and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE).24 Excel 2016 was used to build the database, R V.3.4.3 software was used to create the ARIMA model, the MATLAB R2016a software was used to create the basic GRNN model and hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model. GeoDetector software was used for SSH test.

Patient and public involvement

In this study, no patients or public was involved.

Ethics

Since no primary data collection was undertaken, no patient or public was involved, no formal ethical assessment or informed consent was required.

Results

Single ARIMA model

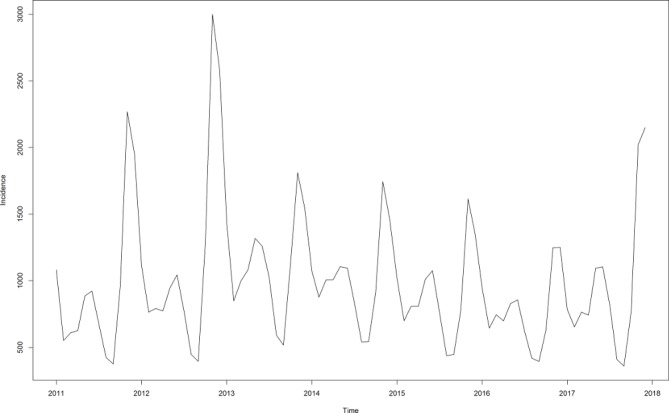

The monthly incidence data of HFRS in China from January 2011 to December 2017 was used to develop the ARIMA model (figure 1). As shown in the original time series graph, the HFRS incidence showed seasonal variation and the period was 12 months (s=12). A slightly declining trend can be seen and it means the time series was not stationary. Trend difference (d=1) and seasonal difference (D=1) were done to eliminate the instability. The ADF test showed that the differenced time sequence was stationary (t statistics was −4.7201, p=0.0100).

Figure 1.

Monthly incidence of HFRS in China from January 2011 to December 2017. HFRS, haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome.

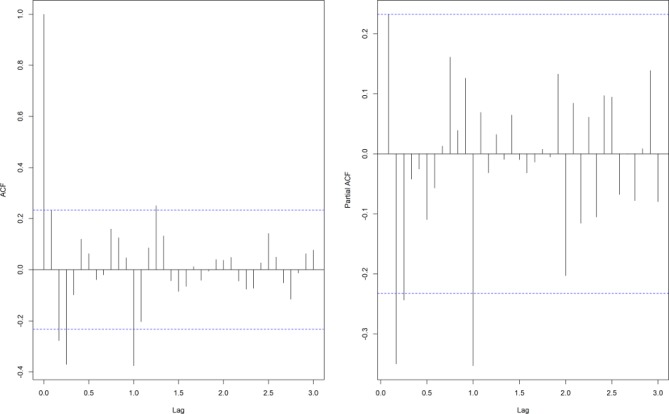

The ACF graph and PACF graph (figure 2) were applied to explore the parameters of the ARIMA model. Four appropriate models were chosen by residual test and filtered by AIC value. The AIC values of ARIMA(1,1,1) (1,1,1)12, ARIMA(1,1,1) (2,1,1)12, ARIMA(2,1,1) (1,1,1)12, ARIMA(2,1,1) (2,1,1)12 were 950.48, 944.68, 940.55 and 936.61, respectively. The ARIMA(2,1,1) (2,1,1)12 model had the lowest AIC value and was chosen as the most suitable model in HFRS prediction. The residual test showed white noise (figure 3).

Figure 2.

The ACF and PACF graphs of differenced HFRS incidence series. ACF, autocorrelation function; HFRS, haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome; PACF, partial autocorrelation function.

Figure 3.

Residual white noise test. ACF, autocorrelation function.

Basic GRNN model

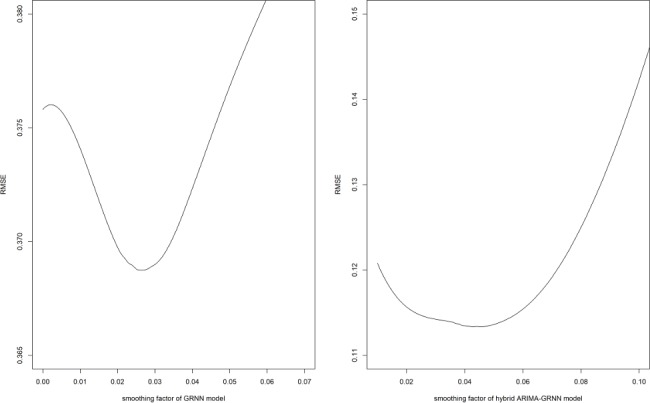

The samples from January 2011 to December 2017 were adopted to develop the network. The last two samples were used as testing samples while the others were training samples. To determine the optimal smoothing factors, a series of smoothing factors were tested. The smoothing factor with the minimum RMSE was selected as the optimal one. Figure 4 shows the RMSE of these smoothing factors and it can be found that the optimal smoothing factor of the one-dimensional input and one-dimensional output GRNN model was 0.027.

Figure 4.

The selection of basic GRNN model and hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model. ARIMA, autoregressive integrated moving average; GRNN, generalised regression neural network; RMSE, root mean square error.

Hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model

The fitted data of ARIMA model from January 2011 to December 2017 were used as the input samples for the GRNN model and the actual HFRS values were used as the output samples to training the hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model. The RMSE of hybrid model was the lowest when the smoothing factor was 0.043 (figure 4), so 0.043 was selected to develop the GRNN model. Subsequently, the forecasting outcomes of ARIMA model from January 2018 to May 2018 were selected as the entry value of the ARIMA-GRNN model, and the output values were the predictive values of the hybrid model.

Finally, all three models had forecasted the HFRS incidence in China from January to May 2018. The forecasting performance parameters of the three models for the fitting and forecasting parts are shown in table 1. The curves of the three models and the actual HFRS incidence series are depicted in figure 5. In this figure, the curves were divided into fitting part and forecasting part by a vertical dashed line, the left is fitting part while the forecasting part is on right.

Table 1.

The fitting and forecasting performance of three models

| Predicting error | Fitting part | Forecasting part | ||||

| MAPE | MAE | RMSE | MAPE | MAE | RMSE | |

| ARIMA | 9.1154 | 89.0302 | 138.8356 | 21.0212 | 175.7042 | 220.6269 |

| GRNN | 10.7332 | 134.5960 | 265.7046 | 19.2029 | 177.0356 | 202.1684 |

| ARIMA-GRNN | 9.6083 | 85.0429 | 140.6426 | 17.8335 | 152.3013 | 196.4682 |

ARIMA, autoregressive integrated moving average; GRNN, generalised regression neural network; MAE, mean absolute error; MAPE, mean absolute percentage error; RMSE, root mean square error.

Figure 5.

The fitting and forecasting curves of three models and the actual HFRS incidence series. ARIMA, autoregressive integrated moving average; GRNN, generalised regression neural network; HFRS, haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome.

Model revision

HFRS incidence time series from January 2011 to December 2017 was partitioned to 12 strata according to their months and SSH was tested. The results showed a q statistic with 0.776 and a p value with 0.000, the SSH was significant. Given these results, the prediction was applied in each strata.

A total of 12 new time series were established and each one has data with same month of each year. The sample size of each series was seven. Since the ARIMA model requires a series with large sample size, thus we built GRNN model to explore whether the strata help improve the model’s performance. The verification data were actual HFRS incidence from January to May 2018, thus we built five revised GRNN models with new series. The relative error of these revised GRNN models were showed in table 2. The average relative error of revised GRNN model was 17.61%, which was lower than 17.83% of original GRNN model. The MAPE, MAE and RMSE of revised model were 17.6095, 163.8000, 169.4751, respectively. These results indicated that the revised model was better than original GRNN model and application of prediction model in different strata was important to model’s performance improvement.

Table 2.

The relative error of GRNN model in HFRS forecasting

| Actual value | Original GRNN model | Revised GRNN model | |||

| Forecasted value | Relative error(%) | Forecasted value | Relative error(%) | ||

| January | 1180 | 843 | 28.56 | 1016 | 13.90 |

| February | 598 | 729 | 21.91 | 765 | 27.93 |

| March | 874 | 828 | 5.26 | 998 | 14.19 |

| April | 959 | 809 | 15.64 | 1081 | 12.72 |

| May | 1253 | 1030 | 17.80 | 1011 | 19.31 |

GRNN, generalised regression neural network; HFRS, haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome.

Discussion

In this study, a hybrid model was constructed based on traditional ARIMA model and basic GRNN model. These three different models were compared in fitting and forecasting performance and the results showed that the hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model was the best model in predicting the monthly reported incidence of HFRS in China. The hybrid model might be a potential decision-making tool to give some suggestion in public health policy decision. However, focusing on SSH and developing prediction model in different strata help improve model’s performance. A hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model built with data of same month of each year might be better than the existing hybrid model.

The characteristic of monthly incidence of HFRS in China is suitable for ARIMA model and GRNN model. As shown in the results, the incidence of HFRS in China has a slight decreasing trend and a bimodal seasonal cases distribution, which are same with other studies.25 26 The incidence reaches peak in winter rapidly and has a longer lasting peak in spring. Autumn to winter peak is the other peak, which is lower than the winter to spring one. Two reasons could explain this seasonal distribution. People are more likely to be exposed to the disease due to increased activities in these two seasons and rodent behaviour changes with climate change.27 28 Besides, the distribution and peak value might change with different hantaviruses types.

The hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model was superior among three models even with imperfect fitting performance. ARIMA model is one of the most commonly used methods in infectious diseases’ prediction and has been proved with high accuracy. In this study, the traditional ARIMA model was used as the basic model for evaluating the performance of other models. The results showed that single ARIMA model and basic GRNN model were better than hybrid model in data fitting according to lower MAE and MAPE. Even some unmeasurable factors may impact data fitting, the forecasting performance should be at the first consideration.21 The MAPE, MAE, RMSE of hybrid model in validation part were lower than single ARIMA model or basic GRNN model. Some studies built the hybrid model with tuberculosis incidence or hand-foot-mouth disease incidence19 29 30 and the results showed that hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model had less error than single model both in modelling and forecasting stage, which is different with our study. Thus we hypothesis that diseases characteristics may affect the model performance and the best predictive model of each infectious disease is different. Model in this study could only fit the incidence of HFRS in China, its performance in other diseases or other nation needs further research.

The time series prediction model was developed as a new potential tool for infectious diseases’ incidence prediction in recent years. In this study, hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model was chose as a potential outbreak warning tool. Same with other disease prediction models, the disease control department could assess the disease developing trend with the help of the hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model. In a short term, the prediction values have same trend with the actual values. It means if the predictive values continue to rise, an outbreak should be alerted. Besides, disease prediction model is developed to evaluate the effectiveness of diseases intervention strategies like vaccine. An effective control measure will make the actual values lower than the predicted results. Something noteworthy is that these two functions are based on short terms. The incidence of infectious disease is influenced by some uncontrollable factors and HFRS is infected by weather, climate, human activities and so on.31–33 These factors may keep stable in a short period and might change in a long run.

SSH is unavoidable in prediction model application and developing model in different strata is a common way to deal with this confounding. In this study, we partitioned the original series to 12 different series by month in order to relieve confounding. Due to the little sample size of each series, seven data are not enough to build ARIMA. Thus the traditional ARIMA model and hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model could not be revised. The GRNN model requires less about sample size so it was revised. Five revised GRNN model showed a better forecasting performance than original GRNN model. These results alert the SSH confounder in time series prediction model application, especially in huge region or diverse territory and the results also remind us of building model in same strata. According to these results, it could be inferred that revised ARIMA model and hybrid model may have better performance than existing models. More data are needed to revise these two models.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. As is shown above, the prediction model was merely developed for short-term forecasting. Maintaining the prediction performance for months or years requires constantly update of data and model. Here we build three new models whose fitting data were HFRS incidence from January 2011 to December 2015 and data from January 2016 to May 2018 were used to verification (online supplementary table S1). It showed that model with new data has higher accuracy. Besides, this study only analysed the incidence of HFRS in China from January 2011 to December 2017 and the sample size is not enough when building model in different strata. Although the revised GRNN model demonstrated that SSH should be considered, the ARIMA-GRNN model were not revised due to little sample size. A time series with more data than this study is required to revise the hybrid model and improve the model’s performance. At last, HFRS incidence data in this manuscript was total incidence in China, we can not explore the performance of these models in provincial incidence prediction. Spatial factor is an important factor that can affect HFRS development, so the applicability of results in this research need further study.

bmjopen-2018-025773supp001.pdf (14.5KB, pdf)

Conclusions

The hybrid ARIMA-GRNN model is superior than the single ARIMA model and basic GRNN model both in fitting and forecasting of monthly incidence of HFRS in China. The data should be kept updated to maintain the forecasting performance. This hybrid model should be considered as a decision-making tool in HFRS prevention and control.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: YJ, YW and ZS designed the study. ZS extracted the data and constructed the database. YW and ZS analysed the data. YW drafted the manuscript. YJ and ZS made critical revision to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors meet the authorship criteria.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data in this manuscript is available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Schmaljohn CS, Hasty SE, Dalrymple JM, et al. Antigenic and genetic properties of viruses linked to hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Science 1985;227:1041–4. 10.1126/science.2858126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ehelepola NDB, Basnayake B, Sathkumara S, et al. Two Atypical Cases of Hantavirus Infections from Sri Lanka. Case Rep Infect Dis 2018;2018:1–6. 10.1155/2018/4069862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Avšič-Županc T, Saksida A, Korva M. Hantavirus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019;21S 10.1111/1469-0691.12291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Latus J, Schwab M, Tacconelli E, et al. Clinical course and long-term outcome of hantavirus-associated nephropathia epidemica, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 2015;21:76–83. 10.3201/eid2101.140861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vaheri A, Strandin T, Hepojoki J, et al. Uncovering the mysteries of hantavirus infections. Nat Rev Microbiol 2013;11:539–50. 10.1038/nrmicro3066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hepojoki J, Vaheri A, Strandin T. The fundamental role of endothelial cells in hantavirus pathogenesis. Front Microbiol 2014;5:727 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pal E, Korva M, Resman Rus K, et al. Sequential assessment of clinical and laboratory parameters in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. PLoS One 2018;13:e197661 10.1371/journal.pone.0197661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bi P, Parton KA. El Niño and incidence of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in China. JAMA 2003;289:176–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang S, Wang S, Yin W, et al. Epidemic characteristics of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in China, 2006-2012. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:384 10.1186/1471-2334-14-384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Du H, Wang PZ, Li J, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in critical patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:191 10.1186/1471-2334-14-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spatiotemporal transmission dynamics of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in China. 2005-2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12. He X, Wang S, Huang X, et al. Changes in age distribution of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: an implication of China’s expanded program of immunization. BMC Public Health 2013;13:394 10.1186/1471-2458-13-394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang Y-wen, Shen Z-zhou, Jiang Y. Comparison of ARIMA and GM(1,1) models for prediction of hepatitis B in China. PLoS One 2018;13:e201987 10.1371/journal.pone.0201987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cao H, Wang J, Li Y, et al. Trend analysis of mortality rates and causes of death in children under 5 years old in Beijing, China from 1992 to 2015 and forecast of mortality into the future: an entire population-based epidemiological study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e15941:e015941 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Petukhova T, Ojkic D, McEwen B, et al. Assessment of autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA), generalized linear autoregressive moving average (GLARMA), and random forest (RF) time series regression models for predicting influenza A virus frequency in swine in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One 2018;13:e198313 10.1371/journal.pone.0198313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yosipof A, Guedes RC, García-Sosa AT. Data Mining and Machine Learning Models for Predicting Drug Likeness and Their Disease or Organ Category. Front Chem 2018;6:162 10.3389/fchem.2018.00162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nair TM. Statistical and artificial neural network-based analysis to understand complexity and heterogeneity in preeclampsia. Comput Biol Chem 2018;75:222–30. 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wei W, Jiang J, Gao L, et al. A New Hybrid Model Using an Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average and a Generalized Regression Neural Network for the Incidence of Tuberculosis in Heng County, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017;97:799–805. 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu W, Guo J, An S, et al. Comparison of Two Hybrid Models for Forecasting the Incidence of Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome in Jiangsu Province, China. PLoS One 2015;10:e135492 10.1371/journal.pone.0135492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rubaihayo J, Tumwesigye NM, Konde-Lule J, et al. Forecast analysis of any opportunistic infection among HIV positive individuals on antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. BMC Public Health 2016;16:766 10.1186/s12889-016-3455-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wei W, Jiang J, Liang H, et al. Application of a Combined Model with Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) and Generalized Regression Neural Network (GRNN) in Forecasting Hepatitis Incidence in Heng County, China. PLoS One 2016;11:e156768 10.1371/journal.pone.0156768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang J-F, Zhang T-L, Fu B-J. A measure of spatial stratified heterogeneity. Ecol Indic 2016;67:250–6. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.02.052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li J, Xu F, Sun Z, et al. Regional differences and spatial patterns of health status of the member states in the “Belt and Road” Initiative. PLoS One 2019;14:e211264 10.1371/journal.pone.0211264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gan R, Chen N, Huang D. Comparisons of forecasting for hepatitis in Guangxi Province, China by using three neural networks models. PeerJ 2016;4:e2684 10.7717/peerj.2684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hansen A, Cameron S, Liu Q, et al. Transmission of haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in china and the role of climate factors: a review. Int J Infect Dis 2015;33:212–8. 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu YX, Feng D, Zhang Q, et al. Key differentiating features between scrub typhus and hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in northern China. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007;76:801–5. 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.76.801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park YH. Absence of a Seasonal Variation of Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome in Yeoncheon Compared to Nationwide Korea. Infect Chemother 2018;50 120–7. 10.3947/ic.2018.50.2.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mills JN, Gage KL, Khan AS. Potential influence of climate change on vector-borne and zoonotic diseases: a review and proposed research plan. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118:1507–14. 10.1289/ehp.0901389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang H, Tian CW, Wang WM, et al. Time-series analysis of tuberculosis from 2005 to 2017 in China. Epidemiol Infect 2018;146:935–9. 10.1017/S0950268818001115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peng Y, Yu B, Wang P, et al. Application of seasonal auto-regressive integrated moving average model in forecasting the incidence of hand-foot-mouth disease in Wuhan, China. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 2017;37:842–8. 10.1007/s11596-017-1815-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Joshi YP, Kim EH, Cheong HK. The influence of climatic factors on the development of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and leptospirosis during the peak season in Korea: an ecologic study. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:406 10.1186/s12879-017-2506-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Han SS, Kim S, Choi Y, et al. Air pollution and hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in South Korea: an ecological correlation study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:347 10.1186/1471-2458-13-347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xiang J, Hansen A, Liu Q, et al. Impact of meteorological factors on hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in 19 cities in China, 2005-2014. Sci Total Environ 2018;636:1249–56. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025773supp001.pdf (14.5KB, pdf)