Abstract

Background

Genetic defects are commonly observed in infertile males, although the majority of cases remain idiopathic. In recent years, the relationship between single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and male infertility has received increasing attention. The objective of this study was to explore the relationship between non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) and single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene (ACE) using ligase detection reaction (LDR)–PCR.

Material/Methods

A retrospective study was performed and we screened 4 ACE SNPs (rs4316, rs4331, rs4343, and rs4362) in 121 NOA cases and 256 control subjects by LDR–PCR. The relationship between SNPs and NOA was analyzed.

Results

ACE SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P=0.089 for rs4331, P=0.089 for rs4343, P=0.089 for rs4316, and P=0.381 for rs4362). The allelic and genotypic frequencies of the 4 SNPs were not significantly different between cases and controls (P=0.123 for rs4331, P=0.123 for rs4343, P=0.123 for rs4316, and P=0.179 for rs4362). Haplotype analysis showed the existence of 3 haplotypes, TGAC, CAGT, and TGAT, which showed statistical significance of 0.889, 0.889, and 0.781, respectively, between cases and controls.

Conclusions

No significant association was found between ACE SNPs rs4316, rs4331, rs4343, or rs4362 and NOA in the Chinese Han population of Northeast China.

MeSH Keywords: Azoospermia; Infertility, Male; Polymorphism, Single Nucleotide

Background

Approximately 15% of couples suffer from infertility, and it is estimated that male infertility is the cause in 50% of cases [1]. Male infertility can be attributed to several factors such as the obstruction or absence of seminal pathways, varicocele, endocrinological disorders, cryptorchidism, and infections [2]. Genetic alterations are another cause of male infertility, especially in patients with NOA. NOA caused by a genetic factor lacks effective treatment, but a clear diagnosis would play an important role in genetic counseling for patients experiencing difficulties in selecting an appropriate fertility treatment.

Genetic defects commonly observed in infertile males include karyotypic abnormalities (such as 47,XXY) and microdeletions of the Y chromosome, although the majority of cases remain idiopathic [3]. In recent years, the relationship between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and male infertility has received increasing attention [4–6]. We previously carried out high-throughput DNA sequencing of 4 SNPs (rs4331, rs4316, rs4343, and rs4362) in the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene (ACE). This revealed that particular genotypes of the 4 SNPs led to changes in the levels of reproductive hormones or seminal plasma biochemical markers in a case–control cohort from Northeast China [7].

ACE is a key enzyme in the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) that converts angiotensin I to angiotensin II. ACE has 2 isoforms: somatic ACE (sACE) and testis-specific ACE (tACE) [8,9]. ACE SNPs have been associated with the risk of preeclampsia in pregnant women [10], hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [11], and migraine [12]. Moreover, the activity of tACE was also associated with infertility in some studies. Animals lacking ACE further suggest a role for the enzyme in male fertility [13,14], and this is supported by the analysis of human samples [15,16]. Additionally, Zalata et al. [17] reported that ACE deletion is associated with abnormal seminal variables. However, Liao et al. [18] showed that ACE polymorphisms were unlikely to contribute to the pathogenesis of male infertility in the Singapore population.

Therefore, in this study, we further explored whether ACE SNPs rs4316, rs4331, rs4343, and rs4362 were associated with NOA Chinese Han patients from Northeast China.

Material and Methods

Subjects

A total of 121 infertile men were collected from the Center for Reproductive Medicine of First Hospital, Jilin University, China between January 2013 and February 2016. Patients were diagnosed with NOA by semen analysis and testicular fine needle aspiration cytology. A total of 256 control subjects were randomly selected from sperm donors at the Human Sperm Bank of Jilin Province between October 2014 and November 2015. Peripheral blood G-banding karyotype analysis and Y chromosome AZF microdeletion detection were carried out for all cases, and those with chromosomal abnormalities or AZF microdeletions were excluded. All patients and controls were of Han ethnicity and were from Northeast China. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University, and all participants provided their written informed consent for participation.

Semen analysis

Samples were obtained as previously described [19]. Semen analysis was performed according to the WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen (2010) with the following cutoff points for healthy semen: normal sperm morphology 4%, semen volume 1.5 ml, total sperm count 39×106/eja, sperm concentration 15×106/ml, and sperm total motility 40%.

Evaluation of biochemical markers

Semen samples were centrifuged at 3,000×g for 15 min to remove spermatozoa and were frozen at −20°C until analysis. The total fructose concentration and neutral alpha-glucosidase in the seminal plasma were evaluated by seminal plasma fructose quantitative assay kit (Indole method) and seminal plasma neutral alpha-glucosidase quantitative assay kit (Enzyme method), respectively (Shenzhen Huakang Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The seminal plasma zinc concentration was measured by seminal plasma zinc quantitative assay kit (modified 5-Br-PAPS) (Shenzhen Huakang Co., Ltd.).

Serum reproductive hormone analysis

The levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), testosterone (T), estradiol (E2), prolactin (PRL), and inhibin B(INHB) were measured by electrochemiluminescence immunoassays using the Elecsys 2010 Chemistry Analyzer (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), based on the manufacturer’s instructions.

SNP selection and genotyping

Genotyping was performed by Shanghai BioWing Applied Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) using LDR–PCR [20]. Genomic DNA was extracted from ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-anticoagulated blood using standard protocols. Target DNA sequences were amplified in a multiplex PCR method using primers shown in Table 1. PCR was conducted in a 20 μl reaction mixture containing 1 × buffer, 50 ng of genomic DNA, 0.6 μl Mg2+ (3.0 mmol/l), 2 μl of deoxynucleotide triphosphates (2.0 mmol/l), 2.0 μl of primer mix, 0.3 μl of 1U Taq Polymerase (Shanghai BioWing Applied Biotechnology Co., Ltd), and 12.2 μl of ddH2O. The reaction was run in a Gene Amp PCR System 9600 thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT, USA) as follows: primary denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, then 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 53°C for 90 s, and extension at 65°C for 30 s, followed by an extra extension at 65°C for 10 min. Primary information for the probes is shown in Table 2. LDR was performed in a 10 μl reaction mixture containing 1×buffer, 1 μl of 2 pmol/μl each probe mix, 0.05 μl of 2 U of Taq DNA ligase (NEB Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), 4 μl ddH2O, and 4 μl multi-PCR product. The fluorescent products of LDR were distinguished by an ABI PRISM 377, and the results were analyzed with GeneMapper software (Applera Corporation, Norwalk, CT, USA). The quality of the genotype was controlled under blinded blood duplications.

Table 1.

Primers of target genes used in the PCR.

| Primer name | Sequence (5-3′) | PCR length | |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs4331 | TGCAGAACACCACTATCAAG | GAGCCACACACCTCCTCCA | 96 |

| rs4343 | GTGAGCTAAGGGCTGGA | CCAGCCCTCCCATGCCCATAA | 109 |

| rs4316 | TTCCTGCTGCTCTGCTACG | TGGGTGACTGTCACCTGTTG | 74 |

| rs4362 | GGAACTGGAACTGGATGATG | TGGGGCCCAGTGGCACAAG | 100 |

Table 2.

Target gene probe sequences of LDR.

| Probe name | Sequence (5′-3′) | LDR length |

|---|---|---|

| rs4331_modify | P-GCTGCCCGTTCTAGGTCCTGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-FAM | |

| rs4331_A | TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTCCTCCAGCTCCTGGGCAGGCAGT | 82 |

| rs4331_G | TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTCCTCCAGCTCCTGGGCAGGCAGC | 84 |

| rs4343_modify | P-GTGGCCATCACATTCGTCAGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-FAM | |

| rs4343_A | TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTACAGGTCTTCATATTTCCGGGAT | 87 |

| rs4343_G | TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTACAGGTCTTCATATTTCCGGGAC | 89 |

| rs4316_modify | P-GGGACCAGCAGAGGGTGCCCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-FAM | |

| rs4316_C | TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTCCTGTTGGGATGCCTCCTGGCTG | 102 |

| rs4316_T | TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTCCTGTTGGGATGCCTCCTGGCTA | 104 |

| rs4362_modify | P-AAGTACCTGGAGCAGAGCGATTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-FAM | |

| rs4362_C | TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGGAACTGGATGATGAAGCTGACG | 112 |

| rs4362_T | TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGGAACTGGATGATGAAGCTGACA | 114 |

Statistical analysis

Clinical data were assessed using the t-test with SPSS Statistics software v. 17.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) assumption was determined online using SHEsis Software (http://analysis.bio-x.cn) for each SNP in cases and controls separately. Allele frequencies were compared using chi-square analyses and Fisher’s exact test (two-sided). SNP genotype frequencies and dominant/recessive model analysis of cases and controls were calculated by logistic regression analysis. P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Haplotype analysis was conducted using SHEs is Software (http://analysis.bio-x.cn/SHEsisMain.htm) [21,22]. Linkage disequilibrium analysis was examined using Haploview Software (http://www.broadinstitute.org/haploview/).

Results

Clinical data analysis

We identified significant differences in age, body mass index (BMI), sperm concentration, semen volume, seminal FSH, LH, T, fructose, α-glucosidase, zinc, and INHB between cases and controls (P<0.05, Table 3). There was no significant difference in semen pH or E2 between the 2 groups (P>0.05, Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of control subjects and cases.

| Variables | Patients (121) | Controls (256) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.00±5.69 | 25.35±5.51 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.31±5.13 | 22.89±3.83 | <0.001 |

| pH | 7.48±0.41 | 7.51±0.06 | 0.314 |

| Sperm density (106/mL) | 0 | 66.88±11.11 | <0.001 |

| Sperm volume (mL) | 2.74±1.49 | 3.69±1.29 | <0.001 |

| Fructose (μmol/eja) | 66.47±57.96 | 20.40±12.88 | <0.001 |

| Alpha-glucosidase (mIU/eja) | 41.25±43.95 | 30.32±18.99 | 0.004 |

| Seminal plasma zinc (μmol/eja) | 7.45±5.31 | 2.91±2.88 | <0.001 |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 19.42±11.62 | 3.35±1.58 | <0.001 |

| LH (mIU/mL) | 9.17±5.20 | 4.96±2.05 | <0.001 |

| PRL (μIU/mL) | 305.11±168.37 | 409.28±215.19 | <0.001 |

| E2 (pg/mL) | 35.46±25.32 | 34.21±11.85 | 0.520 |

| T (nmol/L) | 12.46±6.90 | 17.72±6.43 | <0.001 |

| INHB (pg/mL) | 51.90±84.52 | 200.93±71.27 | <0.001 |

P<0.05 has statistical significance.

Allele and genotype association analysis

We genotyped the ACE SNPs rs4316, rs4331, rs4343, and rs4362 in NOA cases and controls after removing failed genotype samples. Genotype and allele frequencies are summarized in Table 4. All SNPs were in HWE (P=0.089 for rs4331, P=0.089 for rs4343, P=0.089 for rs4316, and P=0.381 for rs4362). However, our case-control analysis of SNP data showed no significant differences between cases and controls (P>0.05). To further explore the genotypes of NOA-related SNPs, binary logistic regression analysis was used for dominance and recessive model analysis with SPSS v.17.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), NOA pathogenicity as a dependent variable, and genetic model as an independent variable. Table 4 shows that there was no association between the 4 SNPs and cases and controls in recessive and dominant genetic models.

Table 4.

Genotypes and dominant/recessive model analysis of NOA-associated SNPs.

| dbsnp code | Cases (n=121) | Controls (n=256) | OR (95% CI) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | MAF% | n (%) | MAF% | |||

| rs4331 | ||||||

| A A | 14 | (153) 63.20 | 42 | (321) 62.70 | 0.978 (0.712~1.342) | 0.889 |

| A G | 61 | 107 | ||||

| G G | 46 | 107 | ||||

| A>G | 60 (24.80) | 149 (29.10) | 0.799 (0.489~1.239) | 0.123* | ||

| GG+AG/AA | 107/14 | 214/42 | 0.987 (0.956~1.019) | 0.417* | ||

| GG/AG+AA | 46/75 | 107/149 | / | / | ||

| rs4343 | ||||||

| A A | 46 | (153) 63.20 | 107 | (321) 62.70 | 1.022 (0.745~1.404) | 0.889 |

| A G | 61 | 107 | ||||

| G G | 14 | 42 | ||||

| G>A | 60 (24.80) | 149 (29.10) | 0.799 (0.489~1.239) | 0.123* | ||

| AA+AG/GG | 107/14 | 214/42 | 0.987 (0.956~1.019) | 0.417* | ||

| AA/AG+GG | 46/75 | 107/149 | / | / | ||

| rs4316 | ||||||

| C C | 14 | (153) 63.20 | 42 | (321) 62.70 | 0.978 (0.712~1.342) | 0.889 |

| C T | 61 | 107 | ||||

| T T | 46 | 107 | ||||

| C>T | 60 (24.80) | 149 (29.10) | 0.799 (0.489~1.239) | 0.123* | ||

| TT+CT/CC | 107/14 | 214/42 | 0.987 (0.956~1.019) | 0.417* | ||

| TT/CT+CC | 46/75 | 107/149 | / | / | ||

| rs4362 | ||||||

| C C | 40 | (143) 59.10 | 96 | (308) 60.20 | 0.957 (0.700~1.306) | 0.780 |

| C T | 63 | 116 | ||||

| T T | 18 | 44 | ||||

| T>C | 58 (23.97) | 140 (27.34) | 1.303 (0.807~2.106) | 0.179* | ||

| CC+CT/TT | 103/18 | 212/44 | 0.986 (0.953~1.020) | 0.408* | ||

| CC/CT+TT | 40/81 | 96/160 | 0.090 (0.000~) | 0.415* | ||

Binary logistic regression analysis;

P<0.05 has statistical significance.

Haplotype analysis

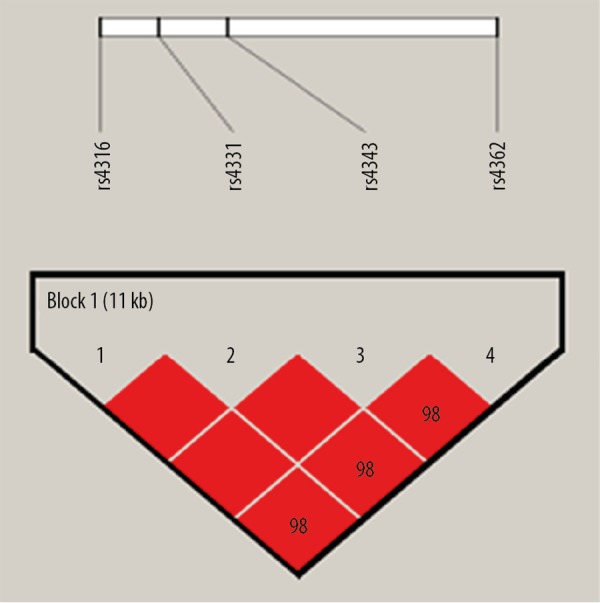

Haploview software was used to analyze the haplotypes of the 4 ACE SNPs distributed on chromosome 17 (Figure 1). The SNPs formed a haplotype block with a coverage of 11 kb in the order ACE c.81C>T (rs4316), ACE c.471A>G (rs4331), ACE c.606G>A (rs4343), and ACE c.1665T>C (rs4362). Three haplotypes were identified in the block: TGAC, CAGT, and TGAT. A comparison of various haplotype frequencies in cases and controls is shown in Table 5; no haplotype was significantly associated with NOA in the present study.

Figure 1.

Haplotype analysis of NOA-associated SNPs in chromosome 17. [ACE c.81C>T (rs4316), ACE c.471A>G (rs4331), ACE c.606G> A (rs4343), and ACE c.1665T> C (rs4362)]. Red squares indicate a complete chain.

Table 5.

Haplotype analysis of NOA-associated SNPs (rs4316, rs4331, rs4343, rs4362).

| Haplotype | Cases frequency(%) | Controls frequency(%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGAC | 59.1 | 59.8 | 0.860 |

| CAGT | 36.8 | 36.9 | 0.971 |

| TGAT | 4.1 | 2.9 | 0.389 |

P<0.05 has statistical significance.

Discussion

ACE was first identified as a key component of the RAS, and ACE on 17q23 encodes 2 isoforms in mammals. sACE is expressed widely in vascular endothelial cells, the kidney, and brain and is associated with blood pressure regulation [8,13,23]. sACE is expressed in testicular Leydig cells, but not expressed in germinal cells [13,24]. In contrast, tACE is specifically expressed in post-meiotic germinal cells during spermiogenesis and in mature spermatozoa [25].

Although there is now a body of evidence implicating the RAS in pathophysiologies associated with reproductive function, the overall importance of the RAS in normal reproductive function is unclear [26]. Previous studies using gene knock-out techniques showed that tACE played an important role in male fertility [15]. Moreover, tACE from healthy functional spermatozoa was reported to have fertilizing ability [23].

The role of ACE gene polymorphism in male infertility patients has been paid attention. A hypothesis has been proposed that SNP polymorphism can lead to changes in the expression of tACE gene, leading to fertilization failure [27]. Novel tACE polymorphisms were identified in European-Americans and African-Americans [28], while Kucera et al. [29] detected different allele frequencies of ACE insertions/deletions in men with a pathological sperm count compared with men with normal fertility. Additionally, Li et al. [27] reported that the ACE SNP rs4316 might be associated with infertility. However, Liao et al. [18] found no significant difference in the frequency of 5 tACE SNPs between patients and controls from Singapore. In our study, 4 tACE SNPs were not found to be associated with NOA.

An interesting phenomenon is that ACE inhibitors improve sperm count and motility in a dose-dependent manner. Infertile males with poor semen quality can be improved by low-dose ACE inhibitors [30]. However, it is not clear whether the effect of this inhibitor is related to changes in tACE activity. The change of ACE SNPs in male infertility is still controversial. Hence, these issues deserve further study in the future.

Conclusions

The present study detected no significant differences in genotype and allele frequencies, or haplotype analysis of ACE SNPs rs4316, rs4331, rs4343, or rs4362 between NOA patients and healthy controls in a Chinese Han population from Northeast China. Together, these findings suggest the existence of ethnic differences in the distribution of SNPs, although larger collaborative studies involving other ethnicities are needed to confirm this.

Footnotes

Source of support: This work was supported by Clinical Medical Research Special Funds of Chinese Medical Association, P.R. China (17020200689)

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Okutman O, Rhouma MB, Benkhalifa M, et al. Genetic evaluation of patients with non-syndromic male infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35:1939–51. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1301-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colaco S, Modi D. Genetics of the human Y chromosome and its association with male infertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:14. doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0330-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oud MS, Ramos L, O’Bryan MK, et al. Validation and application of a novel integrated genetic screening method to a cohort of 1,112 men with idiopathic azoospermia or severe oligozoospermia. Hum Mutat. 2017;38:1592–605. doi: 10.1002/humu.23312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato Y, Hasegawa C, Tajima A, et al. Association of TUSC1 and DPF3 gene polymorphisms with male infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35:257–63. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-1052-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortés-Rodriguez M, Royo JL, Reyes-Palomares A, et al. Sperm count and motility are quantitatively affected by functional polymorphisms of HTR2A, MAOA and SLC18A. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018;36:560–67. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang R, Xi Q, Zhang H, et al. Chloride channel accessory 4 (CLCA4) gene polymorphisms and non-obstructive azoospermia: a case-control study. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:2043–48. doi: 10.12659/MSM.915393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang J. Doctor degree. Jilin University; Changchun: 2016. Identification of non-obstructive azoospermia associated single nucleotide variations by targeted high-throughput sequencing. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esther CR, Jr, Howard TE, Marino EM, et al. Mice lacking angiotensin-converting enzyme have low blood pressure, renal pathology and reduced male fertility. Lab Invest. 1996;74:953–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krege JH, John SW, Langenbach LL, et al. Male-female differences in fertility and blood pressure in ACE-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;375:146–48. doi: 10.1038/375146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abedin Do A, Esmaeilzadeh E, Amin-Beidokhti M, et al. ACE gene rs4343 polymorphism elevates the risk of preeclampsia in pregnant women. J Hum Hypertens. 2018;32:825–30. doi: 10.1038/s41371-018-0096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan Y, Meng L, Zhou Y, et al. Genetic polymorphism of angiotensin-converting enzyme and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8639. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abedin-Do A, Pouriamanesh S, Kamaliyan Z, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene rs4343 polymorphism increases susceptibility to migraine. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23:698–99. doi: 10.1111/cns.12712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagaman JR, Moyer JS, Bachman ES, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme and male fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2552–57. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foresta C, Mioni R, Rossato M, et al. Evidence for the involvement of sperm angiotensin converting enzyme in fertilization. Int J Androl. 1991;14:333–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1991.tb01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi YY, He L. SHEsis, a powerful software platform for analyses of linkage disequilibrium, haplotype construction, and genetic association at polymorphism loci. Cell Res. 2005;15:97–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, Zhang Z, He Z, et al. A partition-ligation- combination-subdivision EM algorithm for haplotype inference with multiallelic markers: update of the SHEsis ( http://analysis.bio-x.cn) Cell Res. 2009;19:519–23. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zalata AA, Morsy HK, Badawy Ael-N, et al. ACE gene insertion/deletion polymorphism seminal associations in infertile men. J Urol. 2012;187:1776–80. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao WX, Roy AC. Lack of association between polymorphisms in the testis-specific angiotensin converting enzyme gene and male infertility in an Asian population. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:299–303. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang H, Wang R, Li L, et al. Clinical feature of infertile men carrying balanced translocations involving chromosome 10: Case series and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e0452. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peach MJ. Renin angiotensin system: Biochemistry and mechanisms of action. Physiol Rev. 1977;57:313–70. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1977.57.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cambien F, Poirier O, Lecerf L, et al. Deletion polymorphism in the gene for angiotensin- converting enzyme is a potent risk factor for myocardial infarction. Nature. 1992;15:641–44. doi: 10.1038/359641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeunemaitre X, Lifton RP, Hunt SC, et al. Absence of linkage between the angiotensin converting enzyme locus and human essential hypertension. Nat Genet. 1992;1:72–75. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shibahara H, Kamata M, Hu J, et al. Activity of testis angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) in ejaculated spermatozoa. Int J Androl. 2001;24:295–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2001.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramaraj P, Kessler SP, Colmenares C, et al. Selective restoration of male fertility in mice lacking angiotensin-converting enzymes by sperm-specific expression of the testicular isozyme. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:371–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sibony M, Gasc JM, Soubrier F, et al. Gene expression and tissue localization of the two isoforms of angiotensin I converting enzyme. Hypertension. 1993;21:827–35. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Speth RC, Daubert DL, Grove KL. Angiotensin II: A reproductive hormone too? Regul Pept. 1999;79:25–40. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(98)00141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li LJ, Zhang FB, Liu SY, et al. Human sperm devoid of germinal angiotensin-converting enzyme is responsible for total fertilization failure and lower fertilization rates by conventional in vitro fertilization. Biol Reprod. 2014;90:125. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.114827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rieder MJ, Taylor SL, Clark AG, et al. Sequence variation in the human angiotensin converting enzyme. Nat Genet. 1999;22:59–62. doi: 10.1038/8760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kucera M, Crha I, Vasků A, et al. Polymorphism of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) and TNF-beta genes in men with disorders of spermatogenesis – pilot study. Ceska Gynekol. 2001;66:313–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okeahialam BN, Amadi K, Ameh AS. Effect of lisinopril, an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor on spermatogenesis in rats. Arch Androl. 2006;52:209–13. doi: 10.1080/01485010500398012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]