Pneumocystis pneumonia is a life-threatening opportunistic fungal infection observed in individuals with severe immunodeficiencies, such as AIDS. Molecules with the ability to bind β-glucan and signal at Fcγ receptors enhance defense against Pneumocystis f.

KEYWORDS: CD4 T cell, Pneumocystis, antibody, beta glucan, chitin, infectious disease, mucosal immunity, opportunistic fungi

ABSTRACT

Pneumocystis pneumonia is a life-threatening opportunistic fungal infection observed in individuals with severe immunodeficiencies, such as AIDS. Molecules with the ability to bind β-glucan and signal at Fcγ receptors enhance defense against Pneumocystis f. sp. murina, though it is unclear whether antibodies reactive with fungal cell wall carbohydrates are induced during Pneumocystis infection. We observed that systemic and lung mucosal immunoglobulins cross-reactive with β-glucan and chitosan/chitin are generated after Pneumocystis infection, with increased quantities within the lung mucosal fluid after challenge. While IgG responses against Pneumocystis protein antigens are markedly CD4+ T cell dependent, CD4+ T cell depletion did not impact quantities of IgG cross-reactive with β-glucan or chitosan/chitin in the serum or mucosa after challenge. Notably, lung mucosal quantities of IgA cross-reactive with β-glucan or chitosan/chitin are decreased in the setting of CD4+ T cell deficiency, occurring in the setting of concurrent reduced quantities of active transforming growth factor β, while mucosal IgM is significantly increased in the setting of CD4+ T cell deficiency. Interleukin-21 receptor deficiency does not lead to reduction in mucosal IgA reactive with fungal carbohydrate antigens after Pneumocystis challenge. These studies demonstrate differential CD4+ T cell-dependent regulation of mucosal antibody responses against β-glucan and chitosan/chitin after Pneumocystis challenge, suggesting that different B cell subsets may be responsible for the generation of these antibody responses, and suggest a potential immune response against fungi that may be operative in the setting of CD4+ T cell-related immunodeficiency.

INTRODUCTION

Host defense against the opportunistic pulmonary fungal pathogen Pneumocystis jirovecii involves the interplay between innate and adaptive immune responses, ultimately initiated through the recognition of specific Pneumocystis antigens. Currently, few Pneumocystis protein antigens have been identified as capable of initiating adaptive host defense responses with good protective benefit in models of infection (1–4). Several Pneumocystis protein antigens demonstrate significant diversity between the different host-restricted Pneumocystis species or are generated from multicopy gene families, hindering the assessment of potential vaccine candidates for protection against human disease (5). The identification of Pneumocystis antigens with greater structural conservation and the less critical requirement for CD4+ T cells in the development of host immune responses may provide an alternate approach for the development of therapies in settings of human Pneumocystis pneumonia susceptibility, such as HIV infection or chemotherapy-related immunosuppression.

The fungal cell wall of Pneumocystis contains the conserved carbohydrates mannan and β-glucan found in most all fungal species (6, 7). Chitin is a conserved fungal cell wall carbohydrate found in a variety of fungal species. Recent studies have demonstrated that Pneumocystis can generate the building blocks for chitin, that a potential chitin synthesis-related enzyme has been identified in Pneumocystis, and that mammalian chitinases are induced in epithelial cells upon exposure to Pneumocystis cell wall components (8, 9). However, Pneumocystis organisms do not react with a recombinant chitinase probe, and chitin oligomers were not detected in a Pneumocystis cell wall preparation by mass spectroscopy, strongly suggesting against the presence of chitin in the Pneumocystis cell wall (10). The carbohydrate components of the Pneumocystis cell wall mannan and β-glucan have been studied as targets of various soluble and membrane-bound pattern recognition receptors (11, 12), and natural IgM antibodies reactive with β-glucan and chitosan/chitin have been identified in catfish and mammals (13). Structurally, β-glucan and chitosan/chitin are comparable to typical thymus-independent type II (TI-2) antigens given their large size, highly repetitive structures, and nonprotein nature (14). Here, we assessed whether adaptive antibody responses are generated against conserved fungal cell wall carbohydrate antigens after murine Pneumocystis murina challenge and define the role of CD4+ T cells in the regulation of these antibody responses. Since the contribution of CD4+ T cells may be restricted to various stages of B cell function, we assessed whether B cells require a CD4+ T cell-sufficient environment for the production of antibodies targeting Pneumocystis fungal cell wall carbohydrates. In addition, since a significant portion of the infection consists of trophozoite forms of Pneumocystis tightly adhering to the apical surfaces of epithelial cells, we sought to specifically understand mucosal antibody production against these carbohydrate antigens and the role of CD4+ T cells in guiding aspects of potential TI-2 antibody responses in the lungs.

While there is evidence that antibodies sufficient for host defense against Pneumocystis are generated in a CD4+ T cell-sufficient environment (15, 16), it is unclear whether antibodies generated in a CD4+ T cell-deficient environment also have some host defense function or modulate aspects of the host immune response. We have previously demonstrated that natural IgM antibodies generated in the absence of exogenous stimuli, containing high quantities of specificities targeting β-glucan and chitosan/chitin, are able to impair the growth of Pneumocystis in the lungs during early stages of infection and impact properties of Th and B cell adaptive immune response differentiation (13). In addition, immunoadhesins with the ability to recognize β-glucan and bind murine Fcγ receptors have also been shown to increase alveolar macrophage-dependent killing of Pneumocystis (17) and complement-dependent killing of Pneumocystis (18) in murine models of infection. Here, we demonstrate that antibodies cross-reactive with β-glucan and chitosan/chitin are products of adaptive antibody responses against Pneumocystis, and we dissect the requirements for CD4+ T cells in isotype class-switching and mucosal antibody production against fungal cell wall carbohydrate antigens.

RESULTS

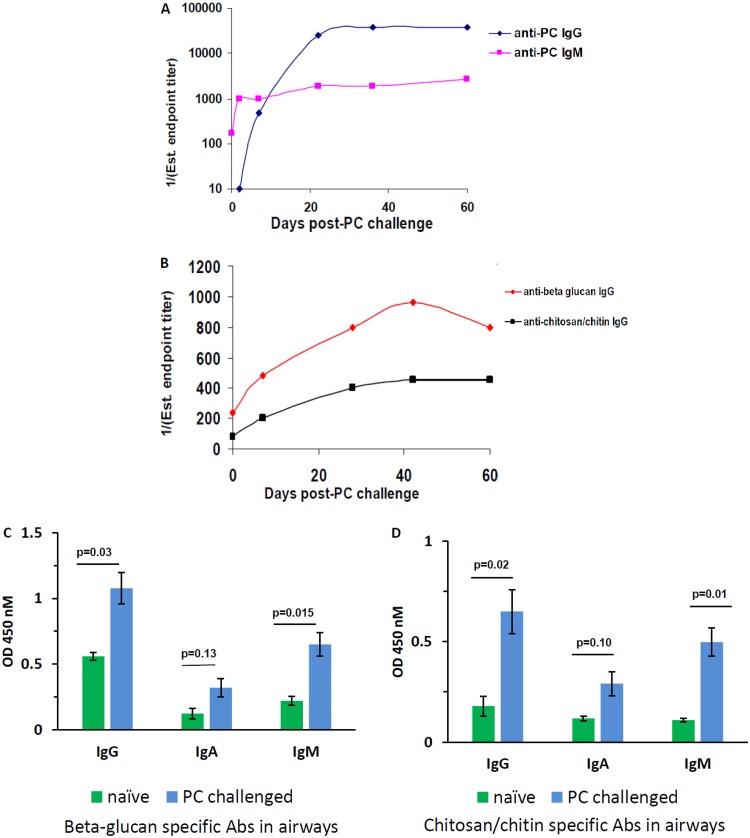

To assess whether adaptive antibody responses against fungal cell wall carbohydrates β-glucan, chitosan/chitin, and mannan are generated, BALB/c wild-type (wt) mice were challenged with Pneumocystis intratracheally. At serial time points, two or three mice were sacrificed, and serum samples were pooled and assessed for antigen (Ag) reactivity in different enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). First, we observed that naive mice possess low levels of IgM reactive with Pneumocystis Ag (PC) prior to challenge at a titer of 1:150, whereas anti-PC IgG is entirely absent at baseline (Fig. 1A). However, both IgG and IgM responses against PC rapidly enhance after challenge, with the IgM response preceding the IgG response, plateauing at 22 and 36 days, respectively. When the serum was probed for IgG reactivity against β-glucan and chitosan/chitin, we noted that an induced IgG response against these antigens developed as well, plateauing somewhat later, at 42 days after infection (Fig. 1B). There were no induced Ig responses against mannan and no serum IgA responses against β-glucan and chitosan/chitin (data not shown). Specific IgG induced against β-glucan and chitosan/chitin after PC challenge had significantly lower titers than the total polyclonal IgG response produced against PC protein antigen. IgG responses targeting the conserved fungal cell wall carbohydrates β-glucan and chitosan/chitin are induced as a consequence of Pneumocystis infection. The titers of induced serum IgG reactive with β-glucan and chitosan/chitin are lower than what we have previously reported with the IgM response, which is near 1:800 titer at baseline in specific-pathogen-free mice and peaks 2 days after Pneumocystis challenge at titers of 1:1,500 to 1:2,000 (13).

FIG 1.

Systemic and mucosal immunoglobulins targeting β-glucan and chitosan/chitin are enhanced after Pneumocystis challenge. BALB/c wt mice were challenged with Pneumocystis intratracheally. Pooled serum from two or three sacrificed mice per time point was probed for IgG and IgM reactivity against Pneumocystis sonicate (PC Ag) (A) or IgG reactivity against β-glucan or chitosan/chitin (B). The estimated endpoint titer is presented over serial measurements through 60 days postchallenge. Panels A and B present representative graphs from two independent experiments. (C and D) Six to eight mice were sacrificed 28 days after Pneumocystis challenge, and BALF, run neat, was compared to that from naive age-matched mice (n = 3) for IgG, IgA, and IgM reactivity against β-glucan (C) or chitosan/chitin (D). The OD450 values are presented, with the background subtracted, and data are from two pooled experiments. Average values are shown with error bars representing the standard errors of the mean (SEM), and P values were calculated by using a Student t test.

To assess how these serum responses might translate into changes in mucosal antibodies, we compared the IgG, IgA, and IgM responses to β-glucan and chitosan/chitin in the BALF of naive mice and mice that had been infected with Pneumocystis 28 days earlier. We observed that Pneumocystis challenge enhanced the quantities of these antibodies reactive with β-glucan and chitosan/chitin in the lung (Fig. 1C and D), with significant increases in the IgG and IgM responses. Of note, these dynamics differ from studies of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) reactivity against PC sonicate, where no reactivity of any isotype is observed at baseline (data not shown); hence, Pneumocystis exposure is not required for the production of the IgG, IgA, and IgM against β-glucan and chitosan/chitin at baseline in the lung.

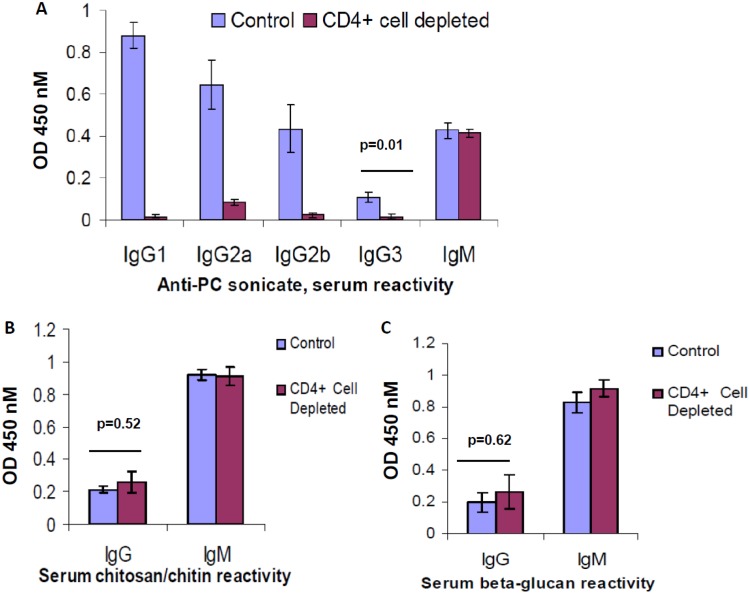

We assessed the role of CD4+ T cells in the production of antibodies reactive with these fungal cell wall carbohydrates after Pneumocystis challenge. Utilizing an anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (MAb), GK1.5, administered prior to challenge and weekly during infection, we chronically depleted mice of CD4+ T cells in secondary lymphoid organs, leading to a phenotype of significant Pneumocystis growth in the lungs after intratracheal challenge. This dose also led to a significant decrease in CD4+ T cells in the lungs compared to what is typically observed in wt mice after infection (Fig. S1). Pneumocystis-infected BALB/c mice that were chronically CD4+ T cell depleted were sacrificed 28 days after challenge, and blood and BALF were analyzed for antibody reactivity against Pneumocystis Ag (PC), as well as β-glucan and chitosan/chitin. In the serum, we observed that chronic CD4+ T cell depletion significantly impaired production of anti-PC IgG isotypes, of which the IgG1 isotype was most dramatically affected, while not influencing quantities of anti-PC IgM (Fig. 2A). However, when serum was probed for anti-β-glucan and anti-chitosan/chitin IgG responses, CD4+ T cell depletion had no effect on levels of these antibodies and also did not influence anti-β-glucan and anti-chitosan/chitin IgM antibodies (Fig. 2B and C). C57BL/6J mice with a conditional mutation in STAT3 in CD4+ T cells (Stat3fl/fl CD4– Cre+), which are deficient in Th17 cells as well as interleukin-21 receptor (IL-21R) signaling, or their respective control strain (Stat3fl/fl CD4– Cre–) were challenged with Pneumocystis and BALF was harvested 28 days after infection. A trend of reduced production of IgA against β-glucan and chitosan/chitin in the BALF of Stat3fl/fl CD4– Cre+ mice compared to the BALF of Stat3fl/fl CD4– Cre– mice was observed, while mucosal IgG levels against these carbohydrates were unaffected (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Hence, an induced IgG response against β-glucan and chitosan/chitin occurs in the absence of the specific requirement for CD4+ T cell expression of STAT3, a pattern consistent with thymus-independent type II antigens.

FIG 2.

Effect of CD4+ T cells on the presence of antibodies targeting PC or fungal cell wall carbohydrates in the serum. BALB/c mice were treated with GK1.5 to deplete CD4+ T cells or with control antibody for 2 weeks and then challenged with Pneumocystis intratracheally, with continued weekly treatment with GK1.5 or control antibody thereafter. At 28 days after challenge, the mice were sacrificed, and serum samples were collected, diluted 1:30, and probed for reactivity by ELISA by at OD450 with the background subtracted, against PC sonicate, with specific analysis of isotype reactivity (A), chitosan/chitin for IgG or IgM reactivity (B), or β-glucan for IgG or IgM reactivity (C). n = 4 or 5 mice/group. Mean values with the SEM are presented, and P values were calculated by using a Student t test.

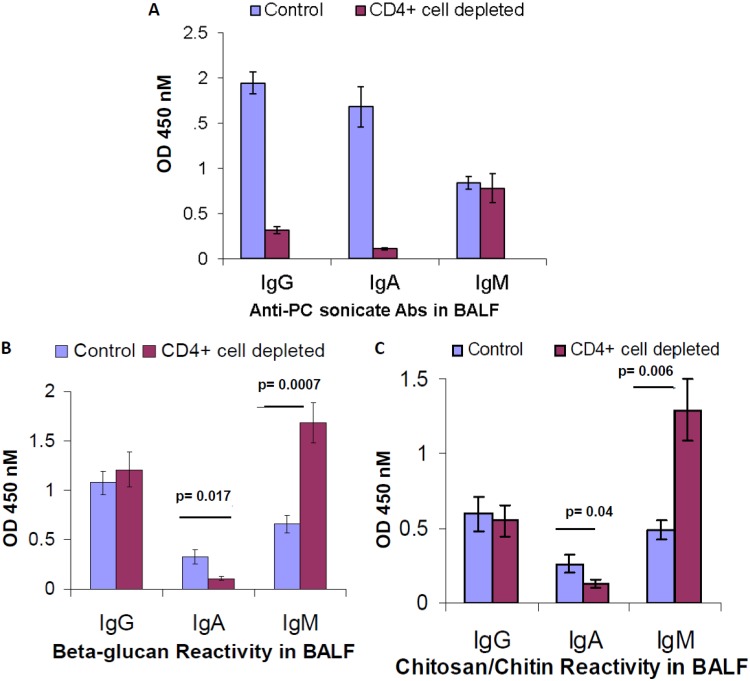

We next assessed whether antibody responses targeting fungal cell wall carbohydrates might be generated at the mucosa, in the absence of CD4+ T cells. Mice were chronically depleted of CD4+ T cells and challenged with Pneumocystis, and BALF was analyzed 28 days after challenge. We assessed serum immunoglobulin reactivity against PC Ag and observed that significant quantities of induced IgG and IgA against PC Ag are present in the mucosa and that these responses are highly impaired in the setting of CD4+ T cell deficiency (Fig. 3A), whereas the anti-PC IgM response is unaffected. At the mucosa, CD4+ T cell depletion notably affected the presence of various isotypes targeting the conserved fungal cell wall carbohydrates, but in a manner different than that by which anti-PC antibodies were affected. While CD4+ T cell depletion did not reduce quantities of IgG targeting β-glucan and chitosan/chitin at the mucosa, quantities of IgA were significantly impaired (Fig. 3B and C). These data demonstrate that the production of specific IgA targeting conserved fungal cell wall carbohydrates at the mucosa critically involves CD4+ T cells. In addition, we observed specific enhancement of quantities of IgM targeting fungal cell wall carbohydrates in the mucosa and, of note, we did not observe enhanced production of these IgM in the serum, suggesting that the phenotype is manifested by local IgM-producing cells associated with the mucosa (Fig. 3B and C).

FIG 3.

Effect of CD4+ T cells on the presence of antibodies targeting PC or fungal cell wall carbohydrates in the BALF. BALB/c mice were treated with GK1.5 to deplete CD4 T cells or with control antibody for 2 weeks and then challenged with Pneumocystis intratracheally, with continued weekly treatment with GK1.5 or control antibody thereafter. At 28 days after challenge, the mice were sacrificed, and BALF was collected and probed neat for reactivity, by isotype, against PC sonicate (A), β-glucan (B), or chitosan/chitin (C). The data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 8 to 10 mice/group). Mean values with the SEM are presented, and P values were calculated by using a Student t test.

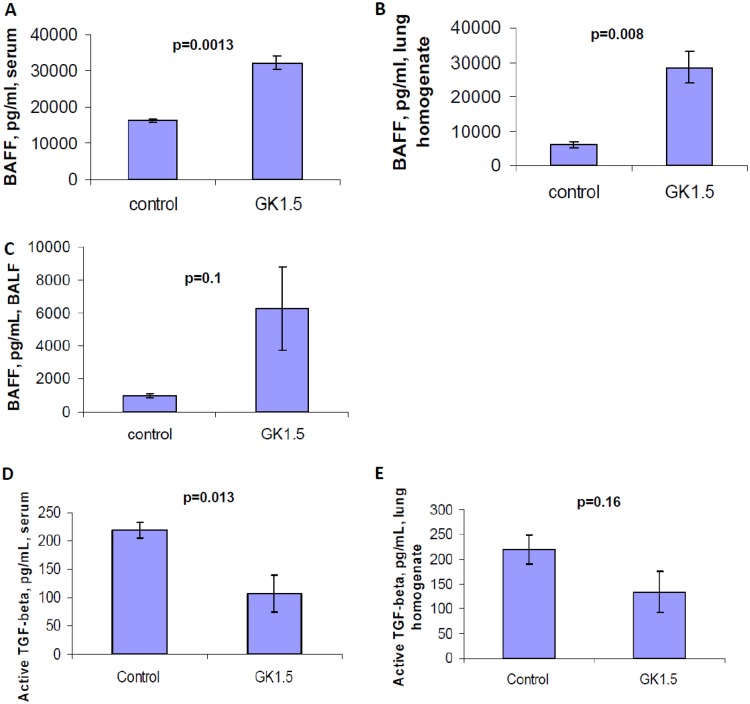

We assessed factors that might be responsible for the perturbation of IgA responses against fungal cell wall carbohydrates in the lung. Since class-switching toward IgG against these fungal cell wall-associated carbohydrates occurred normally in the serum, we questioned whether specific IgA isotype-class switch signals might be impaired in the setting of CD4+ T cell deficiency. Mucosal IgA class switch factors include transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), which is considered a CD4+ T cell-related isotype class-switch factor, and the cytokines TNFSF13B (BAFF) and TNFSF13 (APRIL), which have been demonstrated to be released by the mucosal epithelium in a CD4+ T cell-independent, Toll-like-receptor-dependent manner (19, 20). We hypothesized that factors promoting CD4+ T cell-dependent and CD4+ T cell-independent class switching toward IgA would both be diminished, leading to the diminished quantities of IgA targeting β-glucan and chitosan/chitin that we observed. We found that while TGF-β levels are decreased in the serum and lung homogenate, the quantities of TNFSF13B were very high, significantly enhanced in the setting of CD4+ T cell depletion (Fig. 4). TGF-β was notably absent in the BALF (data not shown). Hence, the impaired release of BAFF/BlyS likely does not account for the impaired IgA response against these carbohydrate Ags, but decreased TGF-β may play a role in these differences.

FIG 4.

Presence of IgA class-switch recombination factors in tissues of mice challenged with Pneumocystis in a setting of chronic CD4+ T cell depletion. Mice were treated with GK1.5 to deplete CD4+ T cells or with control antibody for 2 weeks and then challenged with Pneumocystis intratracheally, with continued weekly treatment with GK1.5 or control antibody thereafter. At 28 days after challenge, the mice were sacrificed, and TNFSF13B was measured in serum (A), lung homogenate (B), and BALF (C). (D and E) Active TGF-β measured from serum (D) and lung homogenate (E). n = 4 or 5 mice/group. Mean values with the SEM are presented, and P values were calculated by using a Student t test.

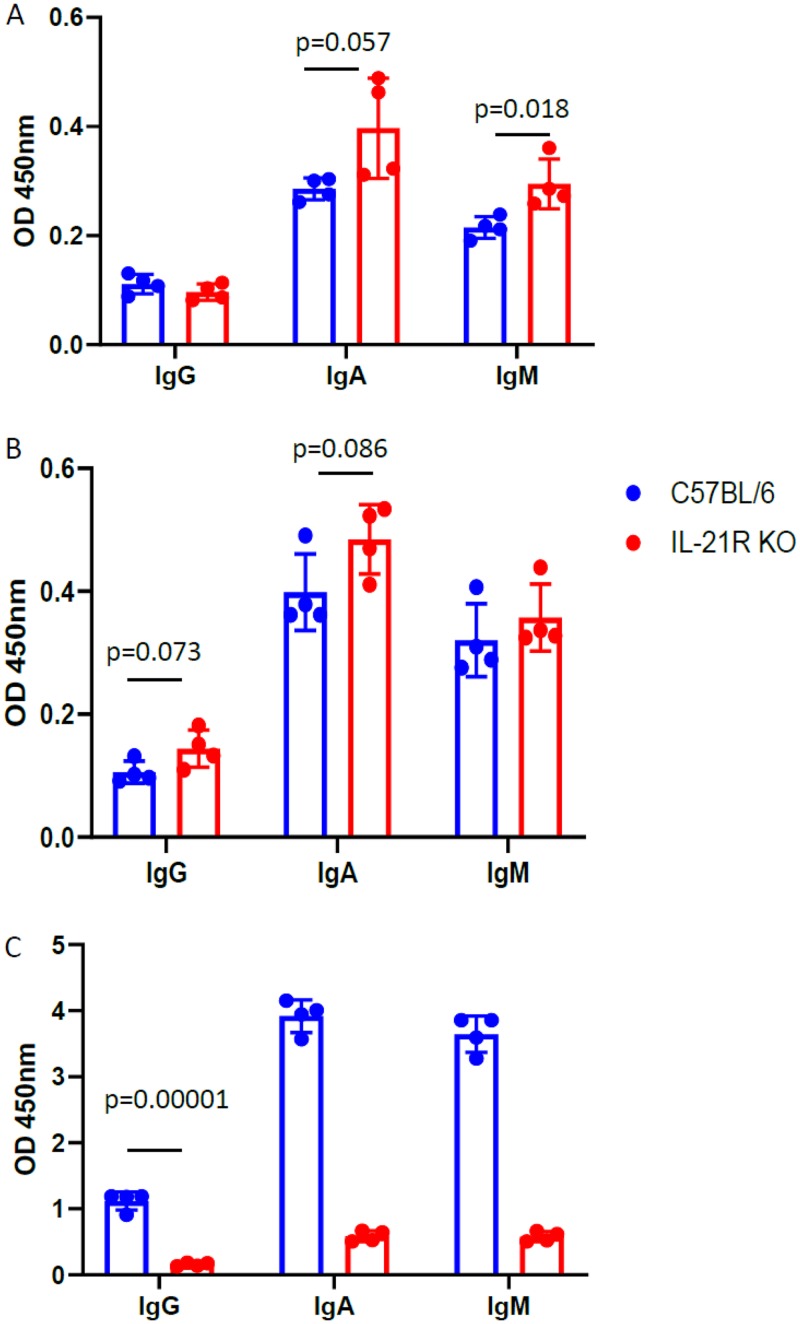

IL-21R signaling is critical for host defense against Pneumocystis in humans and mice, and IL-21 is another factor guiding B cell survival and class switch recombination (21, 22). It has been shown that IL-21 is a critical factor in production of IgA against microbiota at the gut mucosa (21). C57BL/6 IL-2R–/– mice were challenged with Pneumocystis, and after 28 days BALF was probed for IgG, IgA, and IgM responses against β-glucan, chitosan/chitin, and PC Ag. We observed that wt C57BL/6J mice make higher quantities of IgA relative to IgG than those observed in the BALB/c strain (Fig. 3B and C, Fig. 5). IL-21R deficiency, however, does not decrease mucosal IgA against carbohydrate antigens but significantly impairs mucosal IgA production against PC antigen compared to levels in wt C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 5). In addition, IL-21R deficiency significantly impairs production of IgG against PC Ag but does not impact production of IgG antibodies reactive with β-glucan or chitosan/chitin (Fig. 5). These data suggest that IL-21R signaling differentially regulates B cells producing antibodies cross-reactive with fungal carbohydrates versus Pneumocystis protein antigens.

FIG 5.

Effect of IL-21R on isotype and production of antibodies targeting PC or fungal cell carbohydrates at the lung mucosa. wt C57BL/6J or IL-21R–/– (IL-21R KO) mice were challenged intratracheally with Pneumocystis, and BALF was collected 28 days after challenge. The BALF was diluted 1:2 and probed for reactivity, by isotype, against β-glucan (A), chitosan/chitin (B), or PC sonicate (C). Each point represents an individual mouse, and error bars reflect the SEM. The P values were calculated by using a Student t test.

DISCUSSION

The generation of Igs reactive with carbohydrates, as evidenced through several vaccines in clinical use (23), is among the most important protective immune responses generated in humans. B cell antigen recognition and activation against carbohydrate antigens can occur through a variety of mechanisms, including through pathways independent of CD4+ T cells. The mechanisms regulating the induction of antibodies against carbohydrate antigens in the setting of Pneumocystis or other mucosal fungal infections are poorly characterized. With studies in murine models demonstrating that a β-glucan-diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine enhanced host defense against systemic and/or mucosal Aspergillus and Candida infection (24, 25) and that a fusion protein with the ability to recognize β-glucan, as well as bind FcRI and FcγRIII receptors, could enhance host defense against Pneumocystis (17), we investigated whether antibody responses reactive with the conserved fungal cell wall carbohydrate β-glucan, as well as antibodies cross-reactive with another conserved fungal cell wall carbohydrate, chitosan/chitin, are induced in the setting of fungal infection. Further, as Pneumocystis pneumonia susceptibility correlates with major defects in adaptive immune responses, and most clearly with diseases that specifically perturb CD4+ T cell function, we questioned how such antibody responses might be affected in the absence of CD4+ T cells. Understanding how CD4+ T cells factor into the production of immune responses at mucosal sites may also help to optimize vaccines against fungal pathogens.

Recent evidence from genomic studies, mass spectroscopy, and substrate-enzyme binding analyses suggests against any significant presence of chitin in Pneumocystis cell walls (10). However, we have previously shown that antibodies cross-reactive with chitosan/chitin exist in the natural IgM antibody repertoire and are rapidly increased after Pneumocystis challenge (13). Prior studies have demonstrated that serum cross-reactive with chitin oligomers binds Pneumocystis organisms (7); more recently, it has been demonstrated that treatment of Pneumocystis organisms with chitinase prior to stimulation of airway epithelial cells inhibited tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) inflammatory responses by airway epithelial cells and macrophages (8). In addition, mammalian chitinases are induced in airway epithelial cells upon Pneumocystis infection (8). Kottom and coworkers recently demonstrated that the synthetic machinery for generation of N-acetylglucosamine, which as a polymer through β-1,4 linkages composes chitin, is an essential structural component of the Pneumocystis cell wall (potentially as a component of mannoprotein or other cell wall structures) and further that inhibition of the UDP–N-acetylglucosamine synthetic pathway impairs growth of Pneumocystis in the lungs of immunosuppressed rats (9). Together, these data suggest that the N-acetylglucosamine, together with other Pneumocystis cell wall components structurally similar to chitosan/chitin, elicits B cell antibody responses cross-reactive with chitosan/chitin. Given that we have previously observed anti-chitosan/chitin IgM in germfree mice, it is possible that these specificities are germ line encoded by B cells and that increased production of these antibodies is elicited in the context of various fungal infections. A candidate B cell population that could mediate production of these antibodies are marginal zone B cells, which express polyreactive IgM receptors, produce class-switched antibodies with generally lower affinity than affinity matured antibodies, and possess broad overlapping antibody specificities to common antimicrobial patterns (26).

Our data demonstrate that antibodies reactive with chitin/chitosan or other specifically N-acetylglucosamine-containing or similar structures are regulated in both CD4+ T cell-dependent and CD4+ T cell-independent mechanisms at the lung mucosa. We observed that intratracheal Pneumocystis challenge led to the slow induction of specific IgG reactive with β-glucan and chitosan/chitin in the serum and that, additionally, 28 days after infection, the quantities of IgG, IgA, and IgM against these antigens were enhanced at the lung mucosal surface. In addition, IgG cross-reactive with β-glucan and chitosan/chitin, but not with mannan, exists at baseline in the sera of specific-pathogen-free mice. Pneumocystis infection did not lead to the induction of antibodies cross-reactive with mannan, and there was no IgG at baseline that was reactive with mannan. The absence of induced Igs cross-reactive with mannan after Pneumocystis challenge may be partially related to the absence of N-linked mannans in the Pneumocystis cell wall (10); however, there were no cross-reactive Abs elicited against the O-linked mannans present in the Pneumocystis cell wall, and these specificities are not found in specific-pathogen-free mice. These data demonstrate, first of all, that specific anti-carbohydrate antibodies reactive with β-glucan and chitosan/chitin are synthesized by the host after challenge with Pneumocystis. In addition, since IgA responses against these carbohydrates were absent in the serum, this finding demonstrates that the induction of local B cell immune responses occurs against β-glucan and chitosan/chitin, with enrichment of specific IgG and IgM, as well at the mucosa, either through trafficking of activated antibody-secreting cells or through local mucosal B cell activation and differentiation. It has been demonstrated that patients with systemic Candida infections have had increased levels of anti-β-glucan antibodies during infection, with reduced quantities of circulating free β-glucan detected in the blood (27). Since these carbohydrates are conserved among almost all fungal species, we hypothesize that the production of these antibodies may occur after exposure to other pathogenic fungi and that during infection, as observed with Pneumocystis, these responses may particularly accumulate at mucosal sites.

We additionally demonstrate that β-glucan is a TI-2-independent antigen and that B cells producing antibodies cross-reactive with chitosan/chitin are regulated similarly to TI-2 antigens. CD4+ T cells are not required for the production of antibodies targeting these antigens, while IgG isotype responses are significantly impaired against PC sonicate, representing predominantly protein antigens that generate strong, high-affinity antibody responses. Hence, antibody responses targeting conserved fungal cell wall carbohydrates may occur in settings of CD4+ T cell insufficiency. We observed heightened mucosal IgM reactive with fungal cell wall carbohydrates in the setting of CD4+ T cell deficiency and Pneumocystis challenge. Taken with the observation that there was no enhancement of IgM responses against PC sonicate at the mucosa and no difference between control mice and CD4+ T cell-depleted mice in quantities of β-glucan and chitosan/chitin IgM in the serum, we argue that perhaps the enhanced IgM mucosal response specific to carbohydrates in the setting of persisting antigen is a primitive host defense mechanism. To reconcile the observation of enhanced quantities of carbohydrate-specific IgM at mucosal surfaces, but not in the serum, we suspect this response requires specific trafficking of IgM antibody-secreting cells to the mucosa. B-1 B cells are responsible for production of natural antibodies with specificities against repetitive epitopes and are found in pleural and peritoneal spaces, as well as at mucosal sites (28). B-1 B cells have been demonstrated to home to the lung during respiratory infections, such as influenza, and are responsible for the majority of protective antiviral IgM produced at the mucosa (29). Given our prior observation that IgM against β-glucan and chitosan/chitin exists in germfree mice (13), we suspect that the enhanced IgM response observed in the lungs in the setting of CD4+ T cell deficiency may be secondary to the migration of B1 subsets to the lung. IgGs against β-glucan and chitin/chitosan exist at baseline in specific-pathogen-free mice and increase with Pneumocystis infection, and the regulation pattern for these antibodies is consistent with TI-2 antigens. In contrast, the induction of mucosal IgA responses cross-reactive against these carbohydrates is CD4+ T cell dependent, suggesting differences in the properties of B cells producing IgG and IgA responses in the lung mucosa and potentially different properties encoding memory for B cells producing these antibodies. This suggests to us that perhaps different B cells are responsible for the production of IgM targeting fungal cell wall carbohydrates versus IgM targeting PC antigen, accounting for their differences in regulation. We hypothesize that the enhanced IgM production against fungal cell wall carbohydrates at the mucosa may represent a primitive host defense pathway, which is activated in the setting of impaired pulmonary defense against Pneumocystis generally and against an increased Pneumocystis pulmonary burden in the lungs.

Our studies suggest that CD4+ T cells are required for the production of fungal cell wall carbohydrate-directed IgA, but not IgG, at the mucosal surfaces of the lung. We observed significantly diminished quantities of IgA in the BALF of β-glucan and chitosan/chitin specific antibodies after Pneumocystis challenge in the setting of chronic CD4+ T cell depletion. IgA responses are local responses, presumably generated as a consequence of regional priming, and we observed no appreciable IgA against these carbohydrates in the serum; thus, we did not consider CD4+ T cell-derived migration of IgA antibody-secreting cells to play a major role in this process. Hence, we hypothesized that CD4+ T cells may make signals that are required for local IgA class-switch recombination. We evaluated whether class-switching factors might impair the production of IgA and evaluated the quantities of TGF-β, which is involved in the CD4+ T cell-dependent IgA class-switching, and BAFF/BlyS/TNFSF13B, a B cell survival factor that is involved in CD4+ T cell-independent IgA class-switch recombination at the mucosa (30). Of note, in mice lacking the TGF-β receptor on B cells there is a notable reduction in the presence of IgA-secreting B cells at mucosal sites (31). We demonstrate that in mice depleted of CD4+ T cells and with reduced IgA against β-glucan and chitosan/chitin after challenge with Pneumocystis, active TGF-β is decreased, suggesting that CD4+ T cell depletion itself may reduce the production of TGF-β. BAFF quantities, in contrast, which are associated with CD4+ T cell-independent IgA class-switch recombination, are significantly enhanced in CD4+ T cell-depleted mice challenged with Pneumocystis. We suspect that CD4+ T cell-dependent IgA class-switch recombination is perturbed in this model potentially by diminishing levels of TGF-β systemically and in the lungs and that IgA class-switch recombination factors that are considered CD4+ T cell independent are unable to compensate for the deficiency of CD4+ T cell-derived factors. We demonstrate that Pneumocystis murina infection leads to the production of antibodies with cross-reactivity against β-glucan and chitosan/chitin, with regulation differing from that observed against Pneumocystis protein antigens, and with relative CD4+ T cell independence in their systemic generation. These antibody responses against fungal carbohydrates, however, differ at the lung mucosa, where the IgA response is CD4+ T cell dependent and the IgM response against these antigens is notably enhanced in the absence of CD4+ T cells. Decreased production of anti-carbohydrate IgA in the setting of CD4+ T cell insufficiency may be related to TGF-β production.

Of note, IL-21R signaling is critical for IgG, IgA, and IgM lung mucosal antibody responses against Pneumocystis Ag but does not appear to impact the production of IgG, IgA, or IgM against β-glucan or chitosan/chitin at the lung mucosa. IL-21 is an important factor in class-switch recombination, and IL-21 receptor signaling has recently been determined to play an important role in the generation of IgA responses against microbiota in the gut in a Th17- and TGF-β-dependent manner (21, 32). Our findings suggest that B cells that produce mucosal antibodies reactive with these carbohydrates in the lung do not require IL-21R signaling in order to produce class-switched antibodies.

The ability to generate large quantities of IgG antibodies targeting β-glucan and chitosan/chitin in the absence of CD4+ T cells, systemically and at the mucosa, suggests a mechanism of host defense potentially operating in the setting of HIV infection or other T cell-based immunodeficiencies. While IgG and IgA antibodies against β-glucan and chitin/chitosan may play a role in host defense, their induction clearly does not prevent the development of Pneumocystis infection. Quantities of these anti-carbohydrate IgG antibodies after Pneumocystis infection increase ∼4-fold from baseline levels but do not increase to the same degree as observed against Pneumocystis sonicate, which contains protein antigens. We suspect that the specificities targeting β-glucan may play a role in fungal organism opsonization, immune-complex Fc receptor signaling, or potentially impairing fungal cell wall remodeling through direct binding to β-glucan. We have previously demonstrated that introduction of a Dectin-1–IgG1 Fc fusion protein diminished neutrophil recruitment to the lung in the setting of a developing infection and further that this molecule could significantly decrease the growth of Pneumocystis in the lungs of SCID mice but was insufficient in preventing infection (17). Although β-glucan is thought to predominate in the cyst form, in contrast to the more abundant trophic form, Dectin-1–IgG1 Fc was sufficient to significantly decrease the Pneumocystis pulmonary burden in the lungs. In addition, the presence of anti-β-glucan antibodies, indeed a heightened anti-β-glucan IgM response at the mucosa, could potentially impact processes such as antigen presentation. We have previously demonstrated that binding of IgM obtained from specific-pathogen-free mice was partially inhibited in the presence of soluble β-glucan and that natural IgM, containing specificities cross-reactive with β-glucan and chitin/chitosan, influenced dendritic cell migration from the lung to the draining lymph nodes in Pneumocystis infection (13).

While the model system employed involved murine intratracheal challenge of Pneumocystis cysts, rather than natural infection in the context of cohousing with Pneumocystis-infected mice, we were able to model a high burden of pulmonary infection and ask questions about the elicitation of anti-carbohydrate antibodies in the setting of advancing Pneumocystis infection and CD4+ T cell deficiency. In future studies it may be helpful to evaluate how these antibody responses evolve after low inoculum exposures.

In sum, we have demonstrated that anti-carbohydrate IgG and IgM are elicited in a TI-2 manner at the mucosa after Pneumocystis infection, and we show that mucosal IgA production is CD4+ T cell dependent, potentially impacted by TGF-β regulation. B1 or MZ B cell subsets may have a role in the production of these antibodies, in turn impacting host recognition of fungal infection at the lung mucosa, in settings of immunodeficiency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Male BALB/cJ mice and male C57BL/6J mice, 6 to 8 weeks of age, and B6.CB17-Prkdcscid/SzJ (C57BL/6J scid) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. C.B-Igh-1b/IcrTac-Prkdcscid (BALB/c scid) mice were obtained from Taconic Farms. Stat3fl/fl CD4–Cre+ and Stat3fl/fl CD4–Cre− mice were bred and maintained in the animal facility of Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, and have been described previously (22). All mice were maintained in a specific-pathogen-free environment in microisolator cages within the animal care facilities of Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh or Tulane University under protocols reviewed and approved by the IACUC at each institution. Mice were provided with water and food ad libitum and received 12-h light/dark cycles.

Chronic in vivo CD4+ T cell depletion.

BALB/c mice were chronically depleted of CD4+ T cells using the rat MAb GK1.5 obtained from National Cell Culture Center. Mice received 200 μg of GK1.5 weekly, intraperitoneally, for 2 weeks prior to Pneumocystis challenge, and weekly treatments of GK1.5 were continued through the course of the infection. This dose of MAb was confirmed to be sufficient for the depletion of CD4+ T cells to <0.5% of the original quantity of CD4+ T cells in the spleen, as measured by staining of CD4 with antibody clone RM4-4 (BD Pharmingen). In addition, this dose leads to sustained depression of CD4+ T cells in the spleen through at least 7 days, at which point GK1.5 is again administered. We additionally confirmed that this dose of GK1.5 significantly decreased the presence of CD4+ T cells in the lung (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) in C57BL/6J mice using a shortened protocol of 3 days GK1.5 pretreatment prior to Pneumocystis challenge, followed by a weekly 200-μg dosage. This dose of GK1.5 also leads to Pneumocystis susceptibility and growth in the lungs in wt BALB/c or C57BL/6J mice. Control mice received weekly treatments of rat IgG at the same dose and administered using the same schedule (Sigma). Both antibodies were dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and kept at –80°C until use.

P. carinii f. sp. muris isolate and infection.

The Pneumocystis inoculum was prepared as previously described (33). Briefly, C57BL/6J scid mice and BALB/c scid mice with Pneumocystis pneumonia were injected with a lethal dose of ketamine/xylazine, and the lungs were aseptically removed and frozen in 1 ml of PBS at –80°C. The lungs were mechanically dissociated in sterile PBS, filtered through sterile gauze, and pelleted at 500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in sterile PBS, and a 1/5 dilution was stained by a modified Giemsa stain (Diff-Quik; Baxter). The number of Pneumocystis cysts was quantified microscopically, and the inoculum concentration was adjusted to 2 × 106 cysts/ml. Gram stains were performed on the inoculum preparations to exclude contamination with bacteria. Mice were anesthetized and intratracheally challenged with the cyst enumerated preparation of 2 × 105 Pneumocystis cysts in 100 μl of PBS.

Serum and BALF collection.

Fluid from the lower respiratory tract was obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage of mice anesthetized with intraperitoneal ketamine/xylazine as described previously (33). Then, 1 ml of BALF was collected from each mouse using sterile PBS. BALF was centrifuged at 350 × g, and the supernatant was stored at –80°C until use. For serum collection in longitudinal studies with mice, small volumes of blood were collected from the periorbital sinus. At the terminal sacrifice of mice, blood was obtained by caudal venipuncture under anesthesia. Serum was isolated from blood by use of serum separator tubes according to the protocol. Serum was stored at –80°C until use.

Detection of antibody responses against Pneumocystis, beta-glucan, mannan, and chitosan/chitin.

Pneumocystis (PC) antigen was prepared as previously described (2) and derived from the lungs of infected BALB/c scid and C57BL/6 scid mice by differential centrifugation to derive organisms, which were then sonicated. PC antigen was normalized to protein concentration after sonication of organisms, dissolved in carbonate buffer (pH 9.5), and seeded onto Nunc-Polysorp 96-well plates at a concentration of 1 μg/ml. Laminarin (Sigma, catalog no. L-9634), derived from the brown alga Laminaria digitata, is composed primarily of β-1,3-linked glucan, the predominant β-glucan linkage found in fungal cell walls (34), with some interspersed β-1,6 glucan linkages. Medium molecular weight chitosan (Sigma, catalog no. 448877), derived from crab shells, is a polymer of chitin that is 75 to 85% deacetylated. Chitosan/chitin was dissolved in 2% (vol/vol) acetic acid/PBS at a concentration of 0.5 to 1 mg/ml and thereafter diluted into PBS. α-1,6-linked mannan (Sigma, catalog no. M7504) derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae was dissolved in PBS. Predictable ELISA reactivity was observed between different lots of laminarin and chitosan/chitin. In individual experiments, all comparisons were made using the same lot of β-glucan or chitosan/chitin. We have previously demonstrated that a recombinant antibody-like protein with the ability to bind β-glucan loses ELISA reactivity against laminarin upon hydrolysis of β-1,3 linkages with laminarinase (17). The percentages of deacetylation and viscosity were similar between different lots of chitosan/chitin used in these experiments. Carbohydrate antigens were seeded at a concentration of 25 μg/ml to Nunc-Polysorp 96-well plates and kept overnight at 4°C. Plates were blocked in 10% fetal bovine serum and 5% milk in PBS, and blocking buffer was used as a dilution buffer for serum and secondary antibodies. Serum was applied in serial dilutions. BALF was run neat or at a 1:2 dilution. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies against murine IgG, IgA, and IgM were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and Southern Biotech. Plates were developed with TMB and quenched with 2 N sulfuric acid. The background for all ELISAs was typically <0.05, determined at an optical density at 450 nm (OD450), and was subtracted in all assays. The estimated endpoint titer was determined by assessing the lowest concentration at which signal was obtained that was two times higher than background. If this value fell between two concentrations, then the titer was approximated relative to the numerical distance between the readings of the upper and lower concentrations.

Measurement of TNFSF13B (BAFF) and active TGF-β.

Levels of TNFSF13B protein, also known as BAFF (B cell activating factor) or BlyS, were measured in the serum, lung homogenates, and BALF by ELISA (R&D Systems). Active TGF-β levels in serum and lung homogenates were measured by ELISA using a TGF-β1 DuoSet (R&D Systems).

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad statistical software. Comparisons between groups were made with the Student t test. Significance was accepted at a P value of <0.05.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01A120033 (to J.K.K.) and F30ES015413 (to R.R.R.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00158-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smulian AG, Sullivan DW, Theus SA. 2000. Immunization with recombinant Pneumocystis carinii p55 antigen provides partial protection against infection: characterization of epitope recognition associated with immunization. Microbes Infect 2:127–136. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)00275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng M, Ramsay AJ, Robichaux MB, Kliment C, Crowe C, Rapaka RR, Steele C, McAllister F, Shellito JE, Marrero L, Schwarzenberger P, Zhong Q, Kolls JK. 2005. CD4+ T cell-independent DNA vaccination against opportunistic infections. J Clin Invest 115:3536–3544. doi: 10.1172/JCI26306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tesini BL, Wright TW, Malone JE, Haidaris CG, Harber M, Sant AJ, Nayak JL, Gigliotti F. 2017. Immunization with Pneumocystis cross-reactive antigen 1 (Pca1) protects mice against Pneumocystis pneumonia and generates antibody to Pneumocystis jirovecii. Infect Immun 85:e00850-16. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00850-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruan S, Cai Y, Ramsay AJ, Welsh DA, Norris K, Shellito JE. 2017. B cell and antibody responses in mice induced by a putative cell surface peptidase of Pneumocystis murina protect against experimental infection. Vaccine 35:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kutty G, Maldarelli F, Achaz G, Kovacs JA. 2008. Variation in the major surface glycoprotein genes in Pneumocystis jirovecii. J Infect Dis 198:741–749. doi: 10.1086/590433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth A, Wecke J, Karsten V, Janitschke K. 1997. Light and electron microscopy study of carbohydrate antigens found in the electron-lucent layer of Pneumocystis carinii cysts. Parasitol Res 83:177–184. doi: 10.1007/s004360050229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker AN, Garner RE, Horst MN. 1990. Immunocytochemical detection of chitin in Pneumocystis carinii. Infect Immun 58:412–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villegas LR, Kottom TJ, Limper AH. 2012. Chitinases in Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Med Microbiol Immunol 201:337–348. doi: 10.1007/s00430-012-0239-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kottom TJ, Hebrink DM, Jenson PE, Ramirez-Prado JH, Limper AH. 2017. Characterization of N-acetylglucosamine biosynthesis in Pneumocystis species: a new potential target for therapy. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 56:213–222. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0155OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma L, Chen Z, Huang DW, Kutty G, Ishihara M, Wang H, Abouelleil A, Bishop L, Davey E, Deng R, Deng X, Fan L, Fantoni G, Fitzgerald M, Gogineni E, Goldberg JM, Handley G, Hu X, Huber C, Jiao X, Jones K, Levin JZ, Liu Y, Macdonald P, Melnikov A, Raley C, Sassi M, Sherman BT, Song X, Sykes S, Tran B, Walsh L, Xia Y, Yang J, Young S, Zeng Q, Zheng X, Stephens R, Nusbaum C, Birren BW, Azadi P, Lempicki RA, Cuomo CA, Kovacs JA. 2016. Genome analysis of three Pneumocystis species reveals adaptation mechanisms to life exclusively in mammalian hosts. Nat Commun 7:10740. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ezekowitz RA, Williams DJ, Koziel H, Armstrong MY, Warner A, Richards FF, Rose RM. 1991. Uptake of Pneumocystis carinii mediated by the macrophage mannose receptor. Nature 351:155–158. doi: 10.1038/351155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steele C, Marrero L, Swain S, Harmsen AG, Zheng M, Brown GD, Gordon S, Shellito JE, Kolls JK. 2003. Alveolar macrophage-mediated killing of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. muris involves molecular recognition by the Dectin-1 beta-glucan receptor. J Exp Med 198:1677–1688. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rapaka RR, Ricks DM, Alcorn JF, Chen K, Khader SA, Zheng M, Plevy S, Bengten E, Kolls JK. 2010. Conserved natural IgM antibodies mediate innate and adaptive immunity against the opportunistic fungus Pneumocystis murina. J Exp Med 207:2907–2919. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mond JJ, Lees A, Snapper CM. 1995. T cell-independent antigens type 2. Annu Rev Immunol 13:655–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roths JB, Sidman CL. 1992. Both immunity and hyperresponsiveness to Pneumocystis carinii result from transfer of CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells into severe combined immunodeficiency mice. J Clin Invest 90:673–678. doi: 10.1172/JCI115910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roths JB, Sidman CL. 1993. Single and combined humoral and cell-mediated immunotherapy of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in immunodeficient scid mice. Infect Immun 61:1641–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rapaka RR, Goetzman ES, Zheng M, Vockley J, McKinley L, Kolls JK, Steele C. 2007. Enhanced defense against Pneumocystis carinii mediated by a novel dectin-1 receptor Fc fusion protein. J Immunol 178:3702–3712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricks DM, Chen K, Zheng M, Steele C, Kolls JK. 2013. Dectin immunoadhesins and pneumocystis pneumonia. Infect Immun 81:3451–3462. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00136-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He B, Xu W, Santini PA, Polydorides AD, Chiu A, Estrella J, Shan M, Chadburn A, Villanacci V, Plebani A, Knowles DM, Rescigno M, Cerutti A. 2007. Intestinal bacteria trigger T cell-independent immunoglobulin A(2) class switching by inducing epithelial-cell secretion of the cytokine APRIL. Immunity 26:812–826. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu W, He B, Chiu A, Chadburn A, Shan M, Buldys M, Ding A, Knowles DM, Santini PA, Cerutti A. 2007. Epithelial cells trigger frontline immunoglobulin class switching through a pathway regulated by the inhibitor SLPI. Nat Immunol 8:294–303. doi: 10.1038/ni1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao AT, Yao S, Gong B, Nurieva RI, Elson CO, Cong Y. 2015. Interleukin-21 promotes intestinal IgA response to microbiota. Mucosal Immunol 8:1072–1082. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elsegeiny W, Zheng M, Eddens T, Gallo RL, Dai G, Trevejo-Nunez G, Castillo P, Kracinovsky K, Cleveland H, Horne W, Franks J, Pociask D, Pilarski M, Alcorn JF, Chen K, Kolls JK. 2018. Murine models of Pneumocystis infection recapitulate human primary immune disorders. JCI Insight 3:91894. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.91894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee CJ, Lee LH, Lu CS, Wu A. 2001. Bacterial polysaccharides as vaccines: immunity and chemical characterization. Adv Exp Med Biol 491:453–471. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1267-7_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torosantucci A, Bromuro C, Chiani P, De Bernardis F, Berti F, Galli C, Norelli F, Bellucci C, Polonelli L, Costantino P, Rappuoli R, Cassone A. 2005. A novel glycoconjugate vaccine against fungal pathogens. J Exp Med 202:597–606. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bromuro C, Romano M, Chiani P, Berti F, Tontini M, Proietti D, Mori E, Torosantucci A, Costantino P, Rappuoli R, Cassone A. 2010. Beta-glucan-CRM197 conjugates as candidates antifungal vaccines. Vaccine 28:2615–2623. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cerutti A, Cols M, Puga I. 2013. Marginal zone B cells: virtues of innate-like antibody-producing lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol 13:118–132. doi: 10.1038/nri3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kondori N, Edebo L, Mattsby-Baltzer I. 2004. Circulating β(1-3) glucan and immunoglobulin G subclass antibodies to Candida albicans cell wall antigens in patients with systemic candidiasis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 11:344–350. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.2.344-350.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato A, Hulse KE, Tan BK, Schleimer RP. 2013. B-lymphocyte lineage cells and the respiratory system. J Allergy Clin Immunol 131:933–957; quiz, 958. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi YS, Baumgarth N. 2008. Dual role for B-1a cells in immunity to influenza virus infection. J Exp Med 205:3053–3064. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tezuka H, Abe Y, Iwata M, Takeuchi H, Ishikawa H, Matsushita M, Shiohara T, Akira S, Ohteki T. 2007. Regulation of IgA production by naturally occurring TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells. Nature 448:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nature06033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borsutzky S, Cazac BB, Roes J, Guzman CA. 2004. TGF-β receptor signaling is critical for mucosal IgA responses. J Immunol 173:3305–3309. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitsdoerffer M, Lee Y, Jager A, Kim HJ, Korn T, Kolls JK, Cantor H, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. 2010. Proinflammatory T helper type 17 cells are effective B-cell helpers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:14292–14297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009234107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolls JK, Habetz S, Shean MK, Vazquez C, Brown JA, Lei D, Schwarzenberger P, Ye P, Nelson S, Summer WR, Shellito JE. 1999. IFN-γ and CD8+ T cells restore host defenses against Pneumocystis carinii in mice depleted of CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 162:2890–2894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Latge JP. 2007. The cell wall: a carbohydrate armour for the fungal cell. Mol Microbiol 66:279–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.