Abstract

CRISPR-Cas genome editing induces targeted DNA damage but can also affect off-target sites. Current off-target discovery methods work using purified DNA or specific cellular models, but are incapable of direct detection in vivo. Here we develop DISCOVER-Seq, a universally applicable approach for unbiased off-target identification that leverages the recruitment of DNA repair factors in cells and organisms. Tracking the precise recruitment of MRE11 uncovers the molecular nature of Cas activity in cells with single-base resolution. DISCOVER-Seq works with multiple guide RNA formats and types of Cas enzymes, allowing characterization of new editing tools. Off-targets can be identified in cell lines, patient-derived iPSCs and during adenoviral editing of mice paving the way for in situ off-target discovery within individual patient genotypes during therapeutic genome editing.

One-sentence summary

DISCOVER-Seq enables unbiased identification of CRISPR-Cas off-targets and molecular characterization of nuclease activity in vivo.

Introduction

CRISPR-Cas genome editing holds great promise for therapeutic applications, but accurate characterization of on- and off-target DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) induced by a Cas-nuclease remains difficult (1). While existing methods identify off-targets in vitro (2–4) and in restricted cellular models (5, 6), they have limitations such as abundant false positives and an inability to operate during in vivo editing. Here we describe DISCOVER-Seq (Discovery of In Situ Cas Off-targets and VERification by Sequencing), a universal approach for unbiased off-target identification and molecular characterization of Cas activity that works in primary cells and in vivo.

Genome editing relies upon repair of a Cas-induced DSB, and we reasoned that monitoring this process could be used to track genome editing and detect off-targets. Catalytically inactive Cas9 binds many more sequences than it cuts, and ChIP-Seq of Cas9 itself yields false positives (7, 8). However, capturing sequences bound by endogenous DNA repair machinery could specifically identify sites of Cas-induced damage.

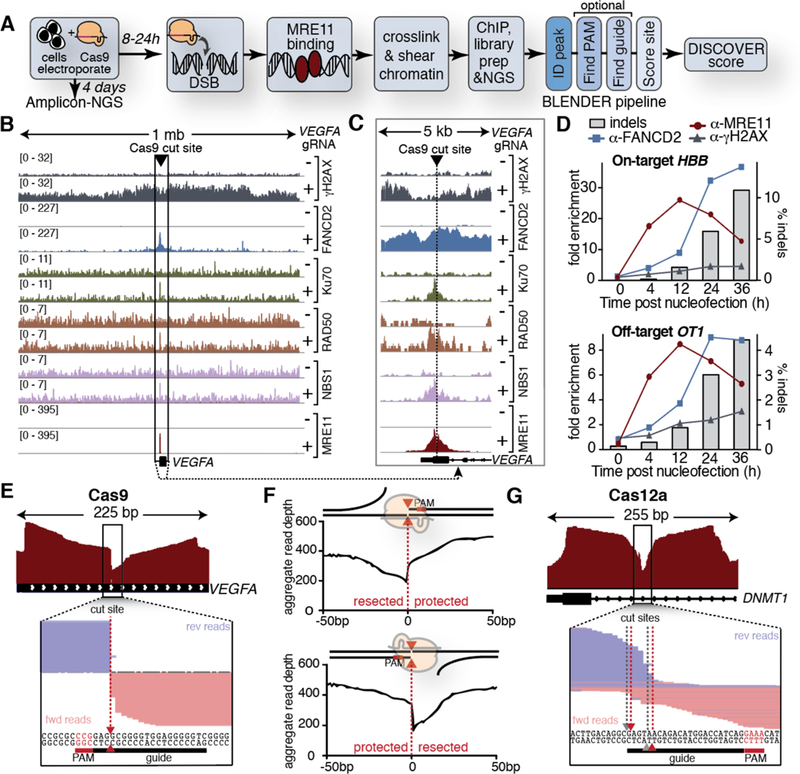

We investigated a set of DNA repair proteins for their ability to identify S.pyogenes Cas9 target sites by ChIP-Seq (Fig. 1A–C). We subsequently focused on the MRE11 subunit of the MRN complex, which is tightly distributed around the Cas9 cutsite, broadly expressed, and has a commercially-available antibody that cross-reacts with murine and human proteins to potentially enable pre-clinical and clinical off-target detection without changing workflow (Fig. S1A–B). MRE11 binding peaked prior to the appearance of indels and was readily detected at a known guide RNA (gRNA) off-target (Fig. 1D, S2) (9). Most MRE11 ChIP-Seq reads precisely ended at the predicted Cas9 cut, enabling identification of the nuclease site with single-base resolution (Fig. 1E, S3A–C). By examining multiple on- and off-targets, we found that Cas9 induces an asymmetric signature depending upon the strand bound by the gRNA (Fig. 1F, S3B), which matches in vitro strand release after Cas9 activity (10). MRE11 binding also correctly identified Cas9’s tendency to create 1bp overhangs when paired with one protospacer we tested (Fig. S4A–B) (11). MRE11 was robustly recruited to sites of Cas12a (Cpf1) editing, but with symmetric and overlapping reads consistent with Cas12a’s mechanism of action (12, 13) (Fig. 1G). MRE11 ChIP-Seq therefore captures the cellular activity of diverse genome editing enzymes at a molecular level. We combined MRE11 ChIP-Seq with custom software, BLENDER (BLunt ENd finDER, https://github.com/staciawyman/blender v1.0.1, Fig. S5), into the DISCOVER-Seq pipeline for in vivo identification of Cas9 off-targets (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1: MRE11 ChIP molecularly characterizes Cas-induced DSBs.

(A) DISCOVER-Seq workflow. (B) DNA repair proteins assemble at a Cas9-induced DSBs. ChIP-Seq tracks for DNA repair proteins in K562 cells edited with VEGFA (+) or non-targeting gRNA (−). (C) Zoomed in data from (B). (D) ChIP-qPCR dynamics of repair protein binding and indel formation (also Fig. S2). (E) Coverage and reads for MRE11 ChIP-Seq at the VEGFA on-target (also Fig. S3B–C). Most reads end in the Cas9 cutsite. (F) Aggregate reads over multiple on- and off-target sites binned into gRNA binding the sense (n=7) or antisense (n=7) strand reveal asymmetric MRE11 recruitment consistent with in vitro models (schematic) (10). (G) MRE11 ChIP-Seq in K562 cells edited with AsCas12a-RNP visualizes multiple overhangs produced by Cas12a (12).

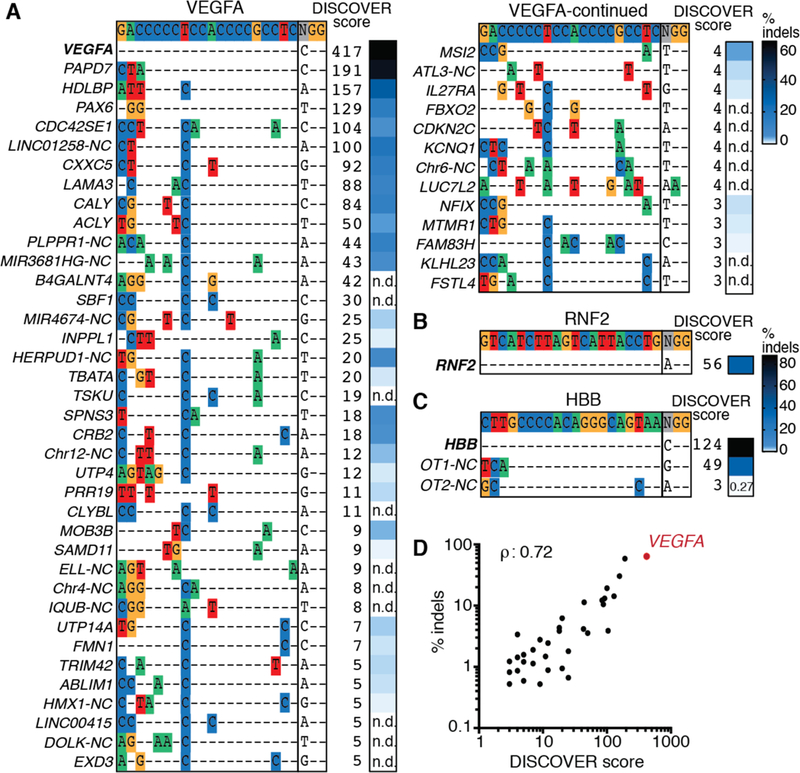

We tested DISCOVER-Seq’s performance at unbiased off-target detection using the well-characterized, promiscuous gRNAs ‘VEGFA_site2’ (5) in human K562 cells and ‘Pcsk9-gP’ (14) in murine B16-F10 cells. DISCOVER-Seq identified 57 off-targets for VEGFA_site2 and 45 off-target sites for gP, which we individually validated by amplicon next-generation sequencing (amplicon-NGS) (Fig. 2A, S6A, Tables S1–2). All off-targets identified by DISCOVER-Seq and tested had indel rates above background (>0.1%). We further tested DISCOVER-Seq using gRNAs with no off-targets targeting RNF2 and ‘Pcsk9-gM’, and an HBB-targeting guide with two off-targets (9). DISCOVER-Seq correctly characterized these gRNAs and identified no false positives (Fig. 2B–C, S6B). We found that gRNAs with an extra 5’-guanine added to protospacers used with PolIII promoters or in vitro transcription reduced off-targets, but non-uniformly (Fig. S7A–C). Regarding enzyme specificity, DISCOVER-Seq also correctly identified fewer off-targets from a high-fidelity Cas9 mutant (15) (Fig. S8A–D). DISCOVER scores were highly correlated with eventual indel frequencies across multiple contexts (Fig. 2D, S9A–C). Comparing DISCOVER-Seq to GUIDE-Seq in K562 cells using the VEGFA_site2 gRNA, we found substantial overlap and also sites uniquely found by each method (Fig. S10A, Table S3). DISCOVER-Seq correlated better with indel rates than GUIDE-Seq, and we empirically determined a DISCOVER-Seq sensitivity threshold of ~0.3% indels (Fig. S10B–C). Overall, DISCOVER-Seq performs well at unbiased and quantitative off-target identification using multiple Cas nucleases and gRNA architectures.

Fig. 2. Unbiased off-target discovery using DISCOVER-Seq.

(A) Off-target sequences identified with DISCOVER-Seq and indel frequencies for VEGFA_site2 in K562s in one representative replicate. NC: non-coding. n.d.: not determined due to difficulties in PCR amplification. (B) and (C) Sequences, DISCOVER scores and indel frequencies for RNF2 and HBB gRNAs in K562s. (D) DISCOVER scores and indel frequencies are correlated (Spearman correlation) (also Fig. S9–10). On-target site in red.

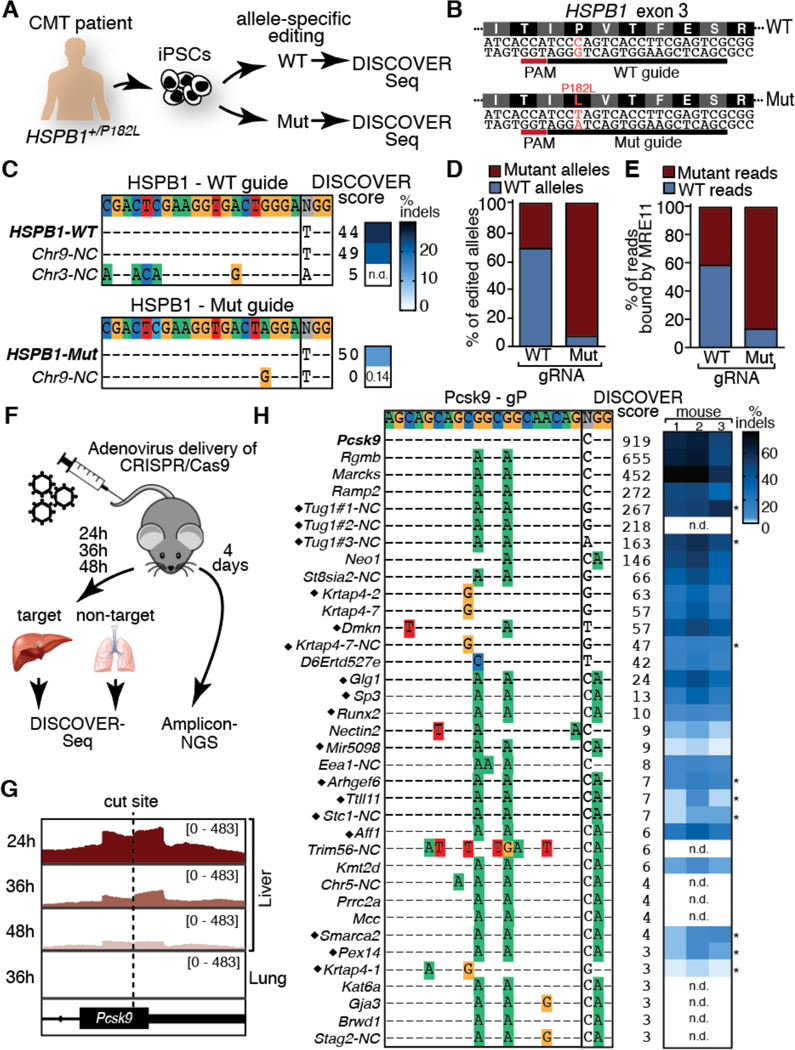

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and other primary cells are often not amenable to off-target discovery due to toxicity of reagents (Fig. S11A–B). We tested DISCOVER-Seq’s ability to identify patient-specific off-targets in iPSCs. We edited iPSCs derived from a Charcot-Marie-Tooth patient with a dominant negative, heterozygous mutation in HSPB1, using HiFi-Cas9 RNPs targeting the wild-type (WT) or mutant (Mut) allele. This challenging application dictates both patient- and allele-specific editing to knockout the mutated allele while sparing the wild-type (Fig. 3A–B). DISCOVER-Seq of the WT-guide identified the HSPB1 on-target and two off-targets, one of them in a duplicated region on chromosome 9, but the Mut-guide solely identified the on-target (Fig. 3C, Table S4). Allelic-dropout analysis of amplicon-NGS showed that the WT-guide edited ~30% Mut alleles, but the Mut-guide cross-edited more than four-fold fewer WT alleles (Fig. 3D). Sequences from DISCOVER-Seq data recapitulated the allele-specificity of the Mut-guide (Fig. 3E). This illustrates DISCOVER-Seq’s ability to perform off-target identification and even determine allelic specificity during preclinical testing in patient-derived cells.

Fig. 3. DISCOVER-Seq in patient-derived iPSCs and in vivo.

(A) CMT patient-derived iPSCs were edited with HiFi-RNPs targeting the wild-type or mutant allele. (B) Patient-specific HSPB1 alleles. (C) DISCOVER scores and indel frequencies of off-targets for HSPB1 WT- and Mut- gRNAs. (D) Allele specificity of WT- and Mut-gRNAs by dropout amplicon-NGS indicate allele-specificity for the Mut-gRNA but not the WT-gRNA. (E) DISCOVER-Seq reads contain identifiable WT or Mut sequences distinguishing allele-specificity. (F) On-target (liver) and off-target (lung) tissues for DISCOVER-Seq (n=2 each) and amplicon-NGS (n=3) were harvested at indicated times after adenoviral injection. (G) DISCOVER-Seq distinguishes nuclease activity in target and non-target tissues at the on-target locus. (H) DISCOVER scores and indel frequencies by amplicon-NGS or ICE (*) for on-and off-targets in mouse livers. Black diamonds: not characterized by VIVO (14). NC: non-coding; n.d.: not determined.

Identifying CRISPR-Cas off-targets during in vivo genome editing is a barrier to clinical translation. DISCOVER-Seq relies on endogenous DNA repair factors thus is theoretically applicable during in vivo editing. We tested in vivo DISCOVER-Seq in a murine setting using the promiscuous ‘Pcsk9-gP’ guide. This system was characterized by ‘VIVO’ (14), which identifies putative off-targets in purified DNA and exhaustively validates potential hits using amplicon-NGS. We used adenoviral infection to deliver Pcsk9-gP+Cas9 or Cas9 alone (Fig. 3F) and found that indels were apparent after four days (Fig. S12A), so performed DISCOVER-Seq on all mice and amplicon-NGS after four days. The on-target locus DISCOVER score in on-target liver was greatest at 24h and declined over time, with no measurable signal in non-targeted lung (Fig. 3G, S12B). Using a pooled-read approach accounting for subtle differences between animals, DISCOVER-Seq identified 36 loci, and we were able to individually amplify 27 of these for indel validation (Fig. 3H, Table S5). All 27 tested sites validated with indel rates 0.9%−78.1%. Very low frequency off-targets identified by VIVO’s in vitro protocol were not detected by in vivo DISCOVER-Seq, but 17 of DISCOVER-Seq’s bona fide NGS-validated off-targets were not VIVO-prioritized because they were lost among VIVO’s nearly 3,000 hits and false positives.

In summary, DISCOVER-Seq is a universal approach for unbiased detection of genome editing off-targets that reveals the molecular action and dynamics of Cas-nucleases in cells and animals. DISCOVER-Seq measures DSBs, providing insight into events occurring prior to the appearance of genome editing outcomes. This could allow identification of cutsites leading to difficult-to-detect outcomes such as translocations and large deletions (16). While in vitro off-target assays are exquisitely sensitive, they are prone to extensive false positives. Additionally, the genomic DNA is stripped of context that affects Cas9 activity, such as chromatin state and modifications. (17–19). By contrast, DISCOVER-Seq measures off-targets in situ in a single-step procedure (Table S6). MREll’s broad conservation suggests applicability of DISCOVER-Seq in organisms beyond mice (20). DISCOVER-Seq’s performance in vivo and in patient-derived iPSCs suggests therapeutic possibilities such as identification in personal genotypes differentiated to target tissues, and real-time discovery in patient biopsy samples during clinical in vivo editing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Marie Johansson for technical support on intravenous tail vein injections and the Gladstone Stem Cell Core for their services.

Funding: J.E.C., B.W., C.D.R., S.K.W., C.D.Y. and K.R.K. are supported by the Li Ka Shing Foundation and Heritage Medical Research Institute. J.E.C. is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH under DP2-HL-141006. C.D.R. is supported by the Fanconi Anemia Research Foundation. J.T.V. is supported by CIRM TRAN1–09292. B.W. is supported by the Fanconi Anemia Research Foundation, a Sir Keith Murdoch Fellowship from the American Australian Association and a NHMRC Early Career Fellowship. This work used the Vincent J. Coates Genomics Sequencing Laboratory at UC Berkeley, supported by NIH S10 OD018174 Instrumentation Grant.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: P.A., M.J.P., M. Morlock and M. Maresca are employees and shareholders of AstraZeneca. J.E.C. is a cofounder of Spotlight Therapeutics. C.D.R. is an employee of Spotlight Therapeutics. J.E.C. has received sponsored research support from AstraZeneca and Pfizer.

Data and materials availability: All non-commercial materials developed in this manuscript are freely available. Unpublished code used in this manuscript is available on GitHub (https://github.com/staciawyman/blender v1.0.1 and https://github.com/staciawyman/cortado v1.0). All sequencing data has been deposited in the Short Read Archive with BioProject accession PRJNA509652.

References and Notes

- 1.Dai W-J et al. , CRISPR-Cas9 for in vivo Gene Therapy: Promise and Hurdles. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 5, e349 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim D et al. , Digenome-seq: genome-wide profiling of CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects in human cells. Nat. Methods. 12, 237–43, 1 p following 243 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai SQ et al. , CIRCLE-seq: a highly sensitive in vitro screen for genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease off-targets. Nat. Methods. 14, 607–614 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron P et al. , Mapping the genomic landscape of CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage. Nat. Methods. 14, 600–606 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai SQ et al. , GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 187–197 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan WX et al. , BLISS is a versatile and quantitative method for genome-wide profiling of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Commun. 8, 15058 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knight SC et al. , Dynamics of CRISPR-Cas9 genome interrogation in living cells. Science. 350, 823–826 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu X et al. , Genome-wide binding of the CRISPR endonuclease Cas9 in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 670–676 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeWitt MA et al. , Selection-free genome editing of the sickle mutation in human adult hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 360ra134 (2016), doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf9336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson CD, Ray GJ, DeWitt MA, Curie GL, Corn JE, Enhancing homology- directed genome editing by catalytically active and inactive CRISPR-Cas9 using asymmetric donor DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 339–344 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shou J, Li J, Liu Y, Wu Q, Precise and Predictable CRISPR Chromosomal Rearrangements Reveal Principles of Cas9-Mediated Nucleotide Insertion. Mol. Cell. 71, 498–509.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zetsche B et al. , Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 163, 759–771 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jinek M et al. , A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 337, 816–821 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akcakaya P et al. , In vivo CRISPR editing with no detectable genome-wide off-target mutations. Nature. 561, 416–419 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vakulskas CA et al. , A high-fidelity Cas9 mutant delivered as a ribonucleoprotein complex enables efficient gene editing in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nat. Med. 24, 1216–1224 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosicki M, Tomberg K, Bradley A, Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR-Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 765–771 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke R et al. , Enhanced Bacterial Immunity and Mammalian Genome Editing via RNA-Polymerase-Mediated Dislodging of Cas9 from Double-Strand DNA Breaks. Mol. Cell. 71, 42–55.e8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kallimasioti-Pazi EM et al. , Heterochromatin delays CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis but does not influence the outcome of mutagenic DNA repair. PLoS Biol. 16, e2005595 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X et al. , Probing the impact of chromatin conformation on genome editing tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 6482–6492 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connelly JC, Leach DRF, Tethering on the brink: the evolutionarily conserved Mre11-Rad50 complex. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 410–418 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okita K et al. , A more efficient method to generate integration-free human iPS cells. Nat. Methods. 8, 409–412 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langmead B, Salzberg SL, Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ENCODE Project Consortium, An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 489, 57–74 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinello L et al. , Analyzing CRISPR genome-editing experiments with CRISPResso. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 695–697 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W et al. , The EMBL-EBI bioinformatics web and programmatic tools framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W580–4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsiau T et al. , Inference of CRISPR Edits from Sanger Trace Data. BioRxiv (2018), doi: 10.1101/251082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aleksandrov R et al. , Protein dynamics in complex DNA lesions. Mol. Cell. 69, 1046–1061.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen MW et al. , Predictable and precise template-free CRISPR editing of pathogenic variants. Nature. 563, 646–651 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Overbeek M et al. , DNA Repair Profiling Reveals Nonrandom Outcomes at Cas9-Mediated Breaks. Mol. Cell. 63, 633–646 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taheri-Ghahfarokhi A et al. , Decoding non-random mutational signatures at Cas9 targeted sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 8417–8434 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verkuijl SA, Rots MG, The influence of eukaryotic chromatin state on CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiencies. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 55, 68–73 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daer RM, Cutts JP, Brafman DA, Haynes KA, The Impact of Chromatin Dynamics on Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing in Human Cells. ACS Synth. Biol. 6, 428–438 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim D, Kim J-S, DIG-seq: a genome-wide CRISPR off-target profiling method using chromatin DNA. Genome Res. 28, 1894–1900 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S, Kim D, Cho SW, Kim J, Kim J-S, Highly efficient RNA-guided genome editing in human cells via delivery of purified Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Genome Res. 24, 1012–1019 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yarrington RM, Verma S, Schwartz S, Trautman JK, Carroll D, Nucleosomes inhibit target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas9 in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115, 9351–9358 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crosetto N et al. , Nucleotide-resolution DNA double-strand break mapping by next- generation sequencing. Nat. Methods. 10, 361–365 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.