Abstract

Objectives.

Accelerated atherosclerotic disease typically complicates rheumatoid arthritis (RA), leading to premature cardiovascular death. Inflammatory macrophages are key effector cells in both, rheumatoid synovitis and the plaques of coronary artery disease (CAD). Whether both diseases share macrophage-dependent pathogenic mechanisms is unknown.

Methods.

Patients with RA or CAD (at least one myocardial infarction) and healthy age-matched controls were recruited into the study. Peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes were differentiated into macrophages. Metabolic profiles were assessed by Seahorse Analyzer, intracellular ATP concentrations were quantified and mitochondrial protein localization was determined by confocal image analysis.

Results.

In macrophages from patients with RA or CAD, mitochondria consumed more oxygen, generated more ATP, and built tight interorganelle connections with the endoplasmic reticulum, forming mitochondria-associated membranes (MAM). Calcium transfer through MAM sites sustained mitochondrial hyperactivity and was dependent on inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3b (GSK3b), a serine/threonine kinase functioning as a metabolic switch. In patient-derived macrophages, inactivated pSer9-GSK3b co-precipitated with the mitochondrial fraction. Immunostaining of atherosclerotic plaques and synovial lesions confirmed that most macrophages had inactivated GSK3b. MAM formation and GSK3b-inactivation sustained production of the collagenase cathepsin K, a macrophage effector function closely correlated with clinical disease activity in RA and CAD patients.

Conclusions.

Re-organization of the macrophage metabolism in RA and CAD patients drives unopposed oxygen consumption and ultimately, excessive production of tissue-destructive enzymes. The underlying molecular defect relates to the deactivation of GSK3b, which controls mitochondrial fuel influx and as such represents a potential therapeutic target for anti-inflammatory therapy.

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Atherosclerosis, Cardiovascular Disease, Inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Unstable atherosclerotic plaques display numerous similarities with bone-erosive synovial lesions in the rheumatoid joint; especially, the dominant role of inflammatory macrophages.1-3 By amplifying inflammatory circuits and directly contributing to atherosclerotic plaque destabilization,4 macrophages may contribute to the enhanced cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients. Despite improved disease control, RA patients have a 2-fold increased risk for myocardial infarction5 with traditional cardiovascular risk factors explaining this only partially.6 Even with mild disease activity, RA increases cardiovascular mortality substantially and is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular complications.7,8 Premature cardiovascular death is the major cause of mortality in RA patients.9 We hypothesized that macrophages in RA and CAD patients share functional abnormalities that promote inflammatory disease.

Macrophages in arthritic joints are hypermetabolic and produce excess amounts of succinate, which is sensed via GPR91 to amplify cytokine release.10 Also, RA macrophages express high amounts of the glycolytic enzyme α-enolase, which is recognized by autoantibodies to induce cytokine production.11 Macrophages of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) excel in glucose uptake and overexpress the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase M2, which functions as a protein kinase, phosphorylates STAT3 and boosts cytokine production.12 The glycolytic intermediate pyruvate controls cell surface expression of immunoinhibitory PD-L1 in CAD macrophages, thus weakening protective immunity.13

The kinase glycogen synthase kinase 3b (GSK3b), first named for the enzyme’s contribution to glycogen storage,14 is now recognized for affecting multiple signaling pathways.15 In most cell types, including macrophages, GSK3b is constitutively active16 and Serine-9 phosphorylation results in its inactivation.17 GSK3b’s function is cell-type and context dependent,16,18 but the kinase was recently implicated in metabolic regulation.19-22

Mitochondria-associated membranes (MAM) are physical contacts between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria. ER-to-mitochondria calcium transfer stimulates calcium-sensitive TCA cycle enzymes to promote mitochondrial metabolism23 and calcium can directly activate the mitochondrial ATPase.24

Here, we report that macrophages from patients that have RA or CAD share a molecular phenotype of mitochondrial hyperactivation, which is mechanistically linked to GSK3b de-activation. Inactivated GSK3b co-precipitates with mitochondria from patient-derived but not from healthy macrophages. Functional consequences include MAM formation, enhancing mitochondrial activation. MAM function and mitochondrial activation were linked to macrophage effector functions; specifically, the release of the potent collagenase cathepsin K. The link between the hypermetabolic state and the tissue-damaging potential of inflammatory macrophages identifies GSK3b as a potential target to correct inappropriate immunity in RA and to prevent progression of atherosclerosis.

METHODS

Patients and controls

The study population included 74 RA patients, 68 CAD patients and 50 age-matched healthy controls. RA patients fulfilled the 2010 diagnostic criteria and were positive for anti-CCP antibodies or for rheumatoid factor and were enrolled between January 2016 and Dec 2017. In parallel, CAD patients who had at least one documented myocardial infarction (> 90 days after the ischemic event) were recruited. Clinical characteristics are given in supplementary tables 1 and 2. Demographically matched healthy individuals were obtained from the Stanford Blood Center. They had no history of autoimmune disease, cancer, chronic viral infection, or any other inflammatory syndrome. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained as appropriate.

Cells and culture

PBMCs were isolated using Lymphoprep (STEMCELL Technologies). CD14+ cells were differentiated into macrophages in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 20 ng/ml M-CSF (eBioscience) and 10% FBS (Lonza) for 5 days as reported previously.12 Macrophages were differentiated by stimulation with 100 U/ml IFN-γ (Sino Biologicals) and 100 ng/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich). Macrophages were detached using StemPro Accutase Cell Dissociation (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher). For inhibition of GSK3b, macrophages were treated with SB216763 (10 µM; Abcam). To inhibit mitochondrial calcium uptake, cells were treated with Ru360 (10 µM; Sigma-Aldrich).

Statistical analysis

Unpaired t-test was applied when comparing groups, and paired t-test when analyzing paired data. Pearson correlation coefficient was used for correlation analysis. All data analyzed by Prism V.6 (GraphPad).

Detailed methods are provided in the supplementary materials.

RESULTS

Increased mitochondrial activity and ATP production in macrophages from patients with RA and CAD

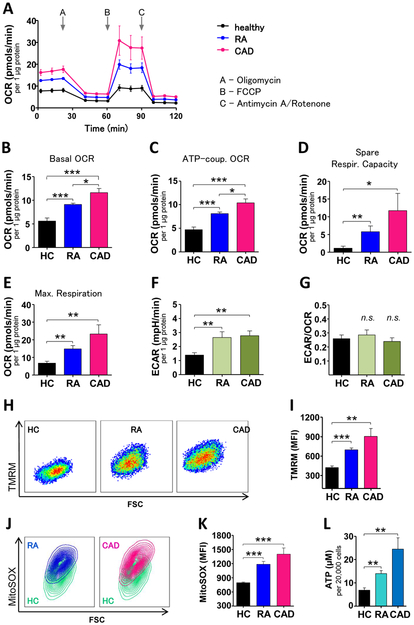

Macrophages were generated from two patient cohorts; patients with autoantibody-positive RA and patients who had CAD-induced cardiac ischemia. To test the metabolic competence, we analyzed mitochondrial oxygen consumption rates (OCR) and extracellular acidification rates (ECAR) by Seahorse extracellular flux assays (figure 1A). Mitochondria from patient-derived macrophages consumed significantly more oxygen than those from healthy age-matched controls (basal OCR, figure 1B). ATP-coupled OCR, probed by oligomycin inhibition of mitochondrial ATP synthase, was higher in disease macrophages, with CAD macrophages outpacing RA macrophages (figure 1C). Similarly, maximal respiration, tested by uncoupling the electron transfer chain with FCCP, was higher in RA and CAD macrophages than in controls (figure 1D). Mitochondria from RA and CAD macrophages had explicitly more reserve capacity to work against imminent energy deficits (figure 1E). In parallel, patient-derived cells intensified glycolysis, captured as higher ECAR (figure 1F). All cohorts had similar ratios of glycolysis to mitochondrial respiration (ECAR/OCR, figure 1G). In line with higher oxygen consumption, mitochondrial membrane potentials, responsible for driving electron transport (figure 1H-I) and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (figure 1J-K) were higher in RA and CAD macrophages. Mitochondrial hyperactivity was already obvious in freshly isolated monocytes (supplementary figure 1A and B). Increased mitochondrial respiration in the patients’ cells resulted in higher ATP production (figure 1L). Together, these data demonstrated that patient-derived macrophages are in a state of heightened mitochondrial activity.

Figure 1. Increased mitochondrial activity and ATP production in macrophages from patients with RA and CAD.

(A) Summarized curves of OCR tracings from Seahorse experiments for all study cohorts (HC; n=7. Patients with RA or CAD; n=10 each). Baseline Respiration (B), respiration coupled to ATP production (C), respiratory spare capacity (D), and maximal respiration (E) were calculated based on OCR. (F) Seahorse analyzer-derived ECAR values and (G) ECAR to OCR ratios. (H, I) Representative dot plots and MFIs from TMRM staining indicative for mitochondrial membrane potential from 6 samples in each group. (J, K) MitoSOX Red staining indicative for mitochondrial ROS. Representative contour plots from RA and CAD macrophages compared to a control sample (green) and summary results from 6 samples in each group. (L) Intracellular ATP concentrations per 20,000 activated macrophages, 6 samples each group. Unpaired t-test was applied. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. All bar graphs show mean ± SEM.

Enhanced mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM) formation and intensified ER-mitochondria calcium transfer in RA and CAD macrophages

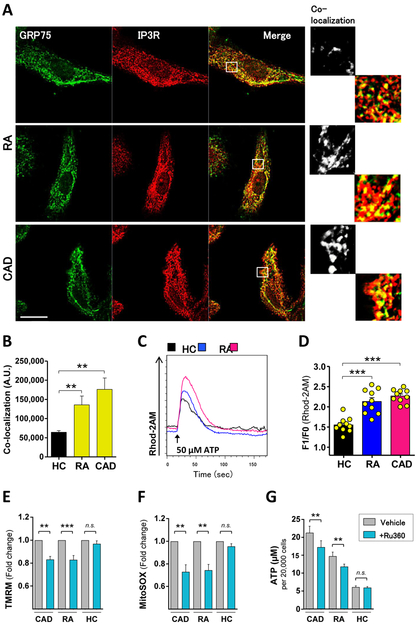

Mitochondria-associated membranes (MAM) are specialized organelle structures connecting mitochondria and the ER to transport lipids and calcium.25,26 To gain information about the structural intactness of mitochondria, we performed co-localization studies of proteins involved in tethering mitochondria to the ER. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3R), calcium channels in the ER outer membrane, connect to mitochondrial membranes through 75 KDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP75). Confocal microscopy revealed IP3R/GRP75 co-localization to a higher degree in RA and CAD macrophages compared to healthy samples (figure 2A). Quantification confirmed a significantly higher protein co-localization, and thus MAM formation, in patient-derived macrophages (figure 2B). The overall signal for IP3R and GRP75 was indistinguishable in the three study cohorts (supplementary figure 2), suggesting that increased co-localization of the markers was reflective of structural rearrangements.

Figure 2. Enhanced mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM) formation and intensified ER-mitochondria calcium transfer in RA and CAD macrophages.

(A) Confocal microscopy of activated macrophages stained with anti-GRP75 (green) and anti-IP3R (red). White boxes represent enlarged areas in the right panel. (B) Quantification of GRP75/IP3R co-localization. Summarized data from six healthy, five RA, and five CAD samples. (C) Representative histogram of mitochondrial calcium uptake after calcium was released from the ER with 50 μM ATP; (D) bar graphs summarizes results from 10 experiments (peak value F1 divided by baseline level F0). (E-G) Mitochondrial membrane potential (n=7 each group), mitochondrial ROS (n=7 each group), and intracellular ATP (n=6 each group) measured after inhibiting mitochondrial calcium influx with Ru360 (10μM). Unpaired t-test (B-D) and paired t-test (E-H). Scale bar 10 μm. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. All bar graphs show mean ± SEM.

To provide biochemical evidence for accelerated MAM formation, we analyzed mitochondrial calcium uptake. Representative curves of mitochondrial calcium influx (figure 2C) illustrated greater calcium uptake in patient-derived macrophages. Quantification (relative increase peak value - baseline value) verified higher calcium uptake through the MAM contact sites in patient-derived cells compared to control cells (figure 2D). Spontaneously increased calcium flux was confirmed for freshly isolated monocytes (supplementary figure1C). To assess the impact of calcium import on mitochondrial activity, RA and CAD macrophages were treated with Ru360, a specific inhibitor of mitochondrial calcium uptake. Disrupting calcium flux caused a decline in mitochondrial membrane potential (figure 2E), diminished ROS production (figure 2F) and lowered ATP generation (figure 2G).

Thus, the signature of mitochondrial hyperactivity in RA and CAD macrophages is associated with structural adaptations, physically connecting mitochondria and the ER by MAM formation to promote calcium transfer.

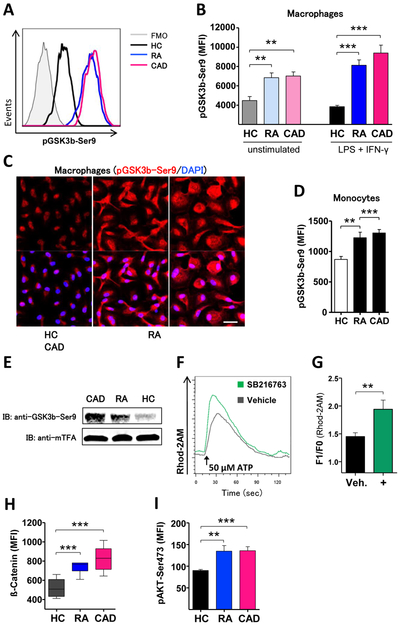

GSK3b is deactivated in patient-derived macrophages

Mitochondrial hyperactivity in RA and CAD macrophages raised the question how mitochondria are instructed to upregulate multiple of their functional domains. The kinase GSK3b has recently been recognized as a regulator of cellular metabolism.20-22 In most cell types, including macrophages, GSK3b’s kinase function is constitutively active.16 To test for the activation status, we quantified pGSK3b-Ser9, the primary target site for inactivation. pGSK3b-Ser9 concentrations were already elevated in resting macrophages from RA and CAD patients (figure 3B), indicating that mitochondria in these cells were primed for higher functional activity. Polarization with LPS and IFN-γ had a minor impact on the phosphorylation status (figure 3A-B). Confocal imaging of ex vivo-macrophages confirmed higher amounts of pGSK3b-Ser9 in patient cells (figure 3C). GSK3b inactivation was already present in freshly isolated monocytes (figure 3D).

Figure 3. GSK3b is deactivated in patient-derived macrophages.

(A) Representative histograms of phosphoflow for pGSK3b-S9 from activated macrophages. Bar graph (B) summarizes results from 6 experiments with unstimulated and from 8 experiments with activated macrophages. (C) Confocal microscopy of GSK3b-Ser9 (red) in activated macrophages. Nuclei were localized by DAPI (blue). (D) Quantification of phosphoflow for pGSK3b-Ser9 in fresh monocytes from 5 experiments. (E) Isolation of mitochondrial fractions and immunoblotting of proteins with antibodies against pGSK3b-S9 and mitochondrial transcription factor A (mTFA) as control protein. Assay was performed 3 times with four healthy, four RA, and four CAD samples. (F) Representative curves and (G) quantification of mitochondrial calcium uptake from 6 experiments after treatment of macrophages from healthy individuals with inhibitor SB216763 (10 μM). (H) Intracellular accumulation of β-catenin in activated macrophages (n=6 in each group). (I) Phosphoflow of Akt-S473. Bar graph summarizes MFIs from 6 samples in each group. Unpaired t-test was applied. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. All bar graphs as well as box and whisker diagrams show mean ± SEM. Scale bar 20 μm.

To understand whether inactivated GSK3b was physically associated with mitochondrial membranes, we isolated mitochondrial protein fractions and probed for the presence of pGSK3b-Ser9. Deactivated GSK3b accumulated in the mitochondrial fraction of CAD macrophages and was also present in mitochondria of RA macrophages, whereas it was barely detectable in mitochondria from healthy donors (figure 3E). To test whether inhibition of GSK3b impacted MAM formation, we treated macrophages from healthy donors with an inhibitor (SB216763) and detected enhanced MAM-driven calcium transfer, suggestive for a role of GSK3b in regulating mitochondrial-ER communication (figure 3F-G).

Accumulation of β-catenin, a consequence of GSK3b inactivation, was clearly detectable in RA and CAD macrophages (figure 3H). The major upstream kinase to phosphorylate GSK3b is protein kinase B (Akt). We measured serine-473 phosphorylation of Akt and found significantly more activated Akt in patient macrophages (figure 3I).

These data established inactivation of GSK3b as a key event in priming mitochondria for high performance by increased MAM signaling.

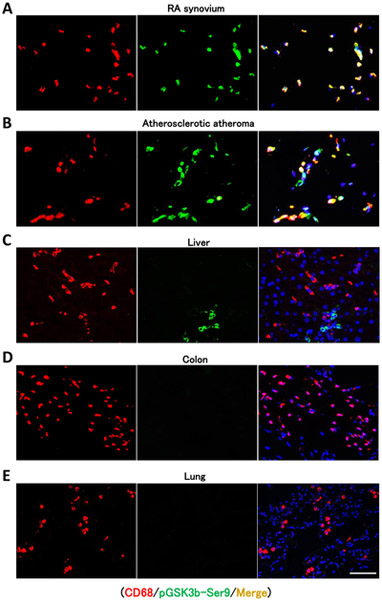

GSK3b is deactivated in macrophages infiltrating into RA synovial tissue and into the atherosclerotic plaque

To investigate whether GSK3b-inactivation is specific for macrophages in disease lesions, we immunostained inactive pGSK3b-Ser9 in tissue biopsies from RA synovium (figure 4A) and from atherosclerotic atheroma (figure 4B). CD68+ tissue macrophages accumulated in the lining layer of synovitic lesions and contained inactivated GSK3b. Similarly, CD68+ cells in the atherosclerotic plaque stained positive for pGSK3b-Ser9. In contrast, in control sections of liver, colon, and lung (figures 4C-E) tissue-infiltrating macrophages stained negative for pGSK3b-Ser9. Liver cholangiocytes stained positive for pGSK3b-Ser9 and serve as positive control. Isotype control staining is shown in supplementary figure 3. These findings indicate that macrophages positive for pGSK3b-Ser9 localize to disease lesions and support the concept that molecular signatures are shared amongst ex vivo-generated monocyte-derived macrophages and lesion-infiltrating cells.

Figure 4. GSK3b is deactivated in macrophages infiltrating into RA synovial tissue and into the atherosclerotic plaque.

Tissue sections were immunostained with anti-CD68 (red), anti-GSK3b-Ser9 (green), and DAPI (blue) and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. (A) RA synovitis from a 36-year-old female patient with nodular disease taken from the left wrist. (B) Atherosclerotic fibro-calcified atheroma from a 76-year-old male patient symptomatic carotid stenosis. Control stainings show tissue sections of (C) liver, (D) colon, and (E) lung. In liver tissue, cholangiocytes stained positive for GSK3-Ser9. Scale bar 50 μm.

GSK3b regulates mitochondrial activity

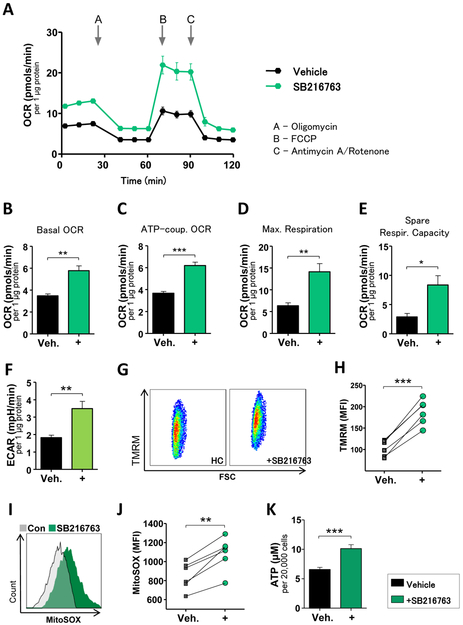

Structural and functional analysis suggested a mechanistic link between GSK3b deactivation, MAM-driven calcium transfer and mitochondrial hyperactivity (figure 2E-F, figure 3E-F). We hypothesized that GSK3b-inhibition might recapitulate the total metabolic phenotype observed in RA and CAD macrophages.

Macrophages from healthy donors were treated with SB216763 to inhibit GSK3b, which resulted in accumulation of β-catenin (supplementary figure 4A), confirming functional deactivation of the kinase. Next, we analyzed mitochondrial respiration before and after GSK3b-inhibition. Seahorse-generated OCR tracings are shown in figure 5A. GSK3b-inhibition stimulated mitochondrial respiration, recapitulating the phenotype observed in disease macrophages (figure 5B) and increased maximal respiration (figure 5C). Also, ATP-coupled OCR and spare respiratory capacity increased (figure 5D-E). Finally, treatment with the inhibitor led to gene induction of the main glucose uptake receptor in macrophages, GLUT-1 (supplementary figure 4B) and glycolytic flux increased (figure 5F).

Figure 5. GSK3b regulates mitochondrial activity.

OCRs (A-E) and ECARs (F) of macrophages from healthy donors (n=7) were measured as in figure 1 after they were pre-treated with vehicle or the inhibitor SB216763 (10 μM, 24 hrs). (G) Representative dot plot and (H) summarizing bar graph of the quantification of mitochondrial membrane potential (n=6). (I) Representative histogram of mitochondrial ROS and (J) summarized results from six experiments. (H) Intracellular ATP concentrations in 20,000 activated macrophages (n=8). All values are mean ± SEM. Paired t-test was applied. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

In line with a phenotype of activated mitochondrial respiration, GSK3b-inhibition in control macrophages increased mitochondrial membrane potential (figure 5G-H), led to formation of larger amounts of mitochondrial ROS (figure 5I-J) and allowed greater ATP production (figure 5H). These data identify GSK3b inactivation as a key event in reprogramming macrophage metabolism.

Mitochondrial activity and MAM function drive macrophage cathepsin K production

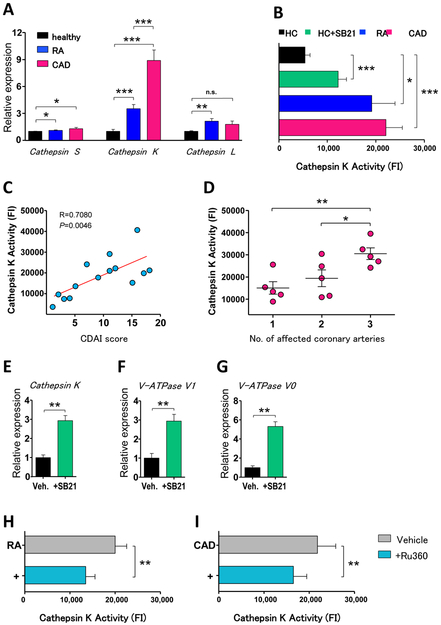

Macrophages are the main facilitator of tissue damage in both, RA joints and atherosclerotic plaques.1,2 We speculated that GSK3b-dependent metabolic reprogramming had functional implications for macrophage effector functions. We analyzed transcriptome profiles for collagenases of the cathepsin family previously reported to be involved in vascular pathology.27 A member of this family is cathepsin K, one of the most potent collagenases described in mammalian cells.28

Cathepsin S transcripts did not separate the study cohorts and cathepsin L was only upregulated in RA macrophages. In contrast, cathepsin K transcripts were strongly upregulated in patient-derived macrophages, being 9-fold higher in cells from CAD patients (figure 6A). To test whether gene induction of cathepsin K resulted in increased collagenase activity, we measured cathepsin K enzyme activity with a specific assay system. In line with transcriptome data, macrophages from RA and CAD patients showed higher enzymatic activity (figure 6B).

Figure 6. Mitochondrial activity and MAM function drive macrophage cathepsin K production.

(A) Gene expression measured by RT-PCR in LPS/IFN-γ-stimulated macrophages (n=6 in each group). Results are fold change compared to controls. (B) Cathepsin K enzyme activity measured in activated macrophages (n=8 each group). Healthy macrophages were treated with SB216763 (10 μM) as indicated, other cells were treated with vehicle. (C) Correlation of vitro cathepsin K activity with disease activity (CADI score) of 14 RA patients. (D) Association of the extent of cardiovascular disease (number of affected coronary arteries) of 15 CAD patients with cathepsin K activity. (E-G) Gene expression of activated macrophages from six healthy donors, SB216763 (10 μM) or vehicle was added as indicated. (H-I) Cathepsin K activity of RA and CAD macrophages treated with Ru360 (10 μM); results from seven samples each group. Unpaired t-test (A-B) and paired t-test (B, E-I) were applied. In figures (C-D) Pearson correlation coefficient was applied. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. All bar graphs show mean ± SEM.

To explore whether cathepsin K activity was related to disease activity in patients, we correlated clinical disease activity scores with in vitro enzyme activity in macrophages. Inflammatory burden in RA patients was measured with clinical disease activity index (CDAI). In CAD patients, we used the number of stenotic coronary vessels assessed by coronary angiography. In both patient cohorts, more active disease in vivo was correlated with higher cathepsin K activity (figure 6C-D).

To establish a mechanistic connection between cathepsin K and GSK3b activity, we treated cells from healthy donors with SB216763. Transcript levels for the collagenase rose 3-fold (figure 6E) and cathepsin K activity increased 2-fold (figure 6B).

Cathepsin K activity is higher in acidic environments.29 Macrophages possess specialized membrane-bound proton pumps to release H+ to acidify the extracellular environment. These vacuolar-type H+-ATPases (V-ATPase) consume mitochondria-generated ATP; they are more effective in energy-rich cells. We explored whether the abundance of ATP in patient macrophages was associated with expression of V-ATPases. Patient-derived cells spontaneously expressed higher transcripts of V-ATPases subunits V0 and V1 (supplementary figure 5) and GSK3b-inactivation in healthy macrophages was followed by marked induction of V-ATPases transcripts (figure 6H-I).

We speculated that mitochondrial activity and MAM function support the tissue destructive phenotype of macrophages. To test this hypothesis, we blocked calcium transfer from the ER to mitochondria and measured cathepsin K activity. Abrogation of calcium influx into mitochondria significantly lowered cathepsin K activity in both, RA and CAD macrophages (figure 6F-G).

In essence, metabolically active macrophages are able to activate the potent collagenase cathepsin K, and this functional domain depends on MAM function and correlates closely with the disease burden in vivo. Disengagement of GSK3b is a critical step in providing mitochondrial energy generation and a prerequisite for collagenase production and activity.

DISCUSSION

Accelerated atherosclerosis has been observed in several rheumatologic diseases. The greatest impact of cardiovascular complications on patient survival can be observed in RA, where premature cardiovascular death is the major cause of mortality.9 However, molecular mechanisms explaining acceleration of cardiovascular disease are not available. Additionally, it is unclear whether pathways for the progression of atherosclerosis are distinct or shared between patients with and without rheumatologic disease. In the present study, we demonstrate that macrophages from RA and CAD patients share a molecular pathway regulated by GSK3b to promote tissue-destructive effector function.

The unexpected finding of this study was the critical role of MAMs in inflammatory macrophages. MAMs are involved in cell death signaling when uncontrolled flooding of the mitochondria with calcium induces apoptosis. Under more physiologic conditions, calcium transfer is dosed and tightly regulated to fine-tune mitochondrial activity by activating mitochondrial ATPase24 and stimulating TCA cycle enzymes23. Current data indicate that macrophages from RA and CAD patients have undergone structural adaptations by increasing physiological MAM contact sites to fulfill their energy demands. Blocking calcium transfer on MAM not only abrogated mitochondrial activation but coordinately also inhibited macrophage effector function by mitigating collagenase activity of cathepsin K. Other inflammatory cascades that were previously reported to be dependent on MAM formation include NLR3P inflammasome activation30 and formation of RIG-MAVS pathogen recognition receptor complexes.31 Our data place MAMs in the center of cellular functionality, spanning from host defense to regulation of innate immunity and tissue destruction. In a simplistic model, MAMs serve as connector between cellular energy production and effector function. This mechanism becomes pathogenic when providing energy for tissue-destructive behavior, thus sustaining conditions of sterile chronic inflammation. Remodeling of the MAM, and with it enhancement of mitochondrial activity, occurs early in the life cycle of macrophages and is already present in precursor monocytes.

The main molecular defect of chronic inflammatory macrophages identified in this study is inactivation of GSK3b; a defect shared by circulating monocytes and differentiated macrophages. GSK3b is constitutively active in most cell types, also in macrophages, and is inhibited in response to stimulation.32 It is considered to be a regulator of survival and cellular intactness; but its eventual role is strongly cell-type and context dependent.16,18 It was reported that active GSK3b associated with mitochondrial quiescence in drosophila oocytes21 and that GSK3-deficient B cells showed higher metabolic activity and increased proliferative capacity.20-22 The current study identifies inactivation of GSK3b as master regulator of metabolic reprogramming in macrophages. Phosphorylation of downstream targets by active GSK3b usually provides an inhibitory effect; this regulatory control of GSK3b in preventing mitochondrial hyperactivity is lost in RA and CAD macrophages. GSK3b-Ser9 localizes to mitochondria and stabilizes calcium transfer at MAM contact sites, a mechanism necessary to increase ATP production and to drive tissue-destructive effector function. Importantly, this pathway is shared between macrophages from RA and CAD patients, indicating a more universal validity in chronic inflammatory diseases. Hypermetabolic macrophages could be induced by SB216763-treatment of healthy cells, a small molecule inhibitor for GSK3b and GSK3a. The functional status of GSK3a was not examined, but the consistent increase in inactivated GSK3b by flow cytometry, immunostaining and immunoblotting in patient samples focused attention to GSK3b.

Inactivation of GSK3b had direct functional consequences: it released transcriptional suppression of cathepsin K, a highly potent collagenase28 that is highly expressed in atherosclerotic lesions and in abdominal aortic aneurysms.33,34 In murine models, cathepsin K deficiency led to smaller atherosclerotic plaques with increased lesion stability.35 In macrophages examined here, upregulation of cathepsin K was coupled to metabolic hyperactivity and induction of other membrane channels, all functioning in concert to achieve optimal enzymatic activity. In essence, the metabolic reprogramming is part of a signature that creates a highly aggressive and pro-inflammatory macrophage.

Interestingly, we observed a close correlation of in vitro cathepsin K activity with disease burden in vivo. Higher cathepsin K activity in macrophages predicted more severe disease in RA and CAD, respectively. This finding underlines the functional relevance of such effector cells and gives rise to the model that metabolically reprogrammed macrophages represent a mechanistic link for the acceleration of atherosclerotic disease.

In summary, the present study identified a pathogenic GSK3b-dependent pathway as a shared defect in inflammatory macrophages of RA and CAD patients. Enhanced formation of MAM structures represents a novel molecular mechanism that drives tissue-destructive effector functions in macrophages. Targeting GSK3b, by restoring its activation status, may allow suppressing effector pathways relevant to RA as well as CAD and provide a novel therapeutic approach towards the increased cardiovascular risk of RA patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AR042527, R01 HL117913, R01 AI108906 and R01 AI108891, R01 AG045779), the Praespero Foundation, and the Cahill Discovery Fund. The authors declare no competing financial interests. M.Z. was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG; ZE 1078/1–1).

References

- 1.Sack U, Stiehl P, Geiler G. Distribution of macrophages in rheumatoid synovial membrane and its association with basic activity. Rheumatol Int 1994;13(5):181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Wal AC, Becker AE, van der Loos CM, et al. Site of intimal rupture or erosion of thrombosed coronary atherosclerotic plaques is characterized by an inflammatory process irrespective of the dominant plaque morphology. Circulation 1994;89(1):36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bories GFP, Leitinger N. Macrophage metabolism in atherosclerosis. FEBS Lett 2017. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore KJ, Tabas I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell 2011;145(3):341–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters MJ, van Halm VP, Voskuyl AE, et al. Does rheumatoid arthritis equal diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease? A prospective study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61(11):1571–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowson CS, Liao KP, Davis JM 3rd, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J 2013;166(4):622–28 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ristic GG, Lepic T, Glisic B, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis is an independent risk factor for increased carotid intima-media thickness: impact of anti-inflammatory treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49(6):1076–81. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warrington KJ, Kent PD, Frye RL, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis is an independent risk factor for multi-vessel coronary artery disease: a case control study. Arthritis Res Ther 2005;7(5):R984–91. doi: 10.1186/ar1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maradit-Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, et al. Increased unrecognized coronary heart disease and sudden deaths in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52(2):402–11. doi: 10.1002/art.20853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Littlewood-Evans A, Sarret S, Apfel V, et al. GPR91 senses extracellular succinate released from inflammatory macrophages and exacerbates rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med 2016;213(9):1655–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bae S, Kim H, Lee N, et al. alpha-Enolase expressed on the surfaces of monocytes and macrophages induces robust synovial inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol 2012;189(1):365–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirai T, Nazarewicz RR, Wallis BB, et al. The glycolytic enzyme PKM2 bridges metabolic and inflammatory dysfunction in coronary artery disease. J Exp Med 2016;213(3):337–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe R, Shirai T, Namkoong H, et al. Pyruvate controls the checkpoint inhibitor PD-L1 and suppresses T cell immunity. J Clin Invest 2017;127(7):2725–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI92167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Embi N, Rylatt DB, Cohen P. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 from rabbit skeletal muscle. Separation from cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase and phosphorylase kinase. Eur J Biochem 1980;107(2):519–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutherland C What Are the bona fide GSK3 Substrates? Int J Alzheimers Dis 2011;2011:505607. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park SH, Park-Min KH, Chen J, et al. Tumor necrosis factor induces GSK3 kinase-mediated cross-tolerance to endotoxin in macrophages. Nat Immunol 2011;12(7):607–15. doi: 10.1038/ni.2043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 1995;378(6559):785–9. doi: 10.1038/378785a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beurel E, Michalek SM, Jope RS. Innate and adaptive immune responses regulated by glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3). Trends Immunol 2010;31(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flugel D, Gorlach A, Michiels C, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylates hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha and mediates its destabilization in a VHL-independent manner. Mol Cell Biol 2007;27(9):3253–65. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00015-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen T, Wong R, Wang G, et al. Acute inhibition of GSK causes mitochondrial remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012;302(11):H2439–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00033.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sieber MH, Thomsen MB, Spradling AC. Electron Transport Chain Remodeling by GSK3 during Oogenesis Connects Nutrient State to Reproduction. Cell 2016;164(3):420–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jellusova J, Cato MH, Apgar JR, et al. Gsk3 is a metabolic checkpoint regulator in B cells. Nat Immunol 2017;18(3):303–12. doi: 10.1038/ni.3664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denton RM. Regulation of mitochondrial dehydrogenases by calcium ions. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1787(11):1309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Territo PR, Mootha VK, French SA, et al. Ca(2+) activation of heart mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation: role of the F(0)/F(1)-ATPase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2000;278(2):C423–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis SC, Uchiyama LF, Nunnari J. ER-mitochondria contacts couple mtDNA synthesis with mitochondrial division in human cells. Science 2016;353(6296):aaf5549. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szabadkai G, Bianchi K, Varnai P, et al. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J Cell Biol 2006;175(6):901–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng XW, Huang Z, Kuzuya M, et al. Cysteine protease cathepsins in atherosclerosis-based vascular disease and its complications. Hypertension 2011;58(6):978–86. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.180935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garnero P, Borel O, Byrjalsen I, et al. The collagenolytic activity of cathepsin K is unique among mammalian proteinases. J Biol Chem 1998;273(48):32347–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kafienah W, Bromme D, Buttle DJ, et al. Human cathepsin K cleaves native type I and II collagens at the N-terminal end of the triple helix. Biochem J 1998;331 ( Pt 3):727–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, et al. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 2011;469(7329):221–5. doi: 10.1038/nature09663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horner SM, Liu HM, Park HS, et al. Mitochondrial-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) form innate immune synapses and are targeted by hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108(35):14590–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110133108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beurel E, Grieco SF, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2015;148:114–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi GP, Sukhova GK, Grubb A, et al. Cystatin C deficiency in human atherosclerosis and aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest 1999;104(9):1191–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI7709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sukhova GK, Shi GP, Simon DI, et al. Expression of the elastolytic cathepsins S and K in human atheroma and regulation of their production in smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest 1998;102(3):576–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samokhin AO, Wong A, Saftig P, et al. Role of cathepsin K in structural changes in brachiocephalic artery during progression of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 2008;200(1):58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.