Abstract

Children of immigrants represent one in four children in the United States and will represent one in three children by 2050. Children of Asian and Latino immigrants together represent the majority of children of immigrants in the United States. Children of immigrants may be immigrants themselves, or they may have been born in the United States to foreign-born parents; their status may be legal or undocumented. We review transcultural and culture-specific factors that influence the various ways in which stressors are experienced; we also discuss the ways in which parental socialization and developmental processes function as risk factors or protective factors in their influence on the mental health of children of immigrants. Children of immigrants with elevated risk for mental health problems are more likely to be undocumented immigrants, refugees, or unaccompanied minors. We describe interventions and policies that show promise for reducing mental health problems among children of immigrants in the United States.

Keywords: children of immigrants, stressors, transcultural, culture specific, parental socialization, mental health

INTRODUCTION

Migration is a worldwide phenomenon, and the United States is the leading destination of international migration (Connor & Lopez 2016). Some immigrants arrive alone, and other immigrants form family units and either arrive with children or have children in the destination country. This review focuses on the mental health of children with immigrant parents, specifically on the experiences of children of Asian and Latino immigrants in the United States. We present consistencies as well as differences in the effects of culture on stressors, parental socialization, and developmental processes, and the effects of these factors, in turn, on the mental health of adolescents from Asian and Latino immigrant families. Our spotlight on these pan-ethnic groups is deliberate, as they collectively represent 77% of immigrants to the United States (26% of US immigrants are of Asian heritage and 51% are of Latino heritage) (Lopez et al. 2015). This review focuses especially on children from Chinese and Mexican immigrant families, as they represent the largest ethnic groups of Asians and Latinos, respectively, in the United States (Lopez et al. 2015).

Understanding the mental health of children of immigrants is important, given the size of the population and its future growth. Children of immigrants currently represent one in four children in the United States and are projected to represent one in three children by the year 2050 (Passel 2011). While US-born parents and their children have a share of the US labor force that is projected to decline by 8.2%, the shares of immigrants and their US-born children are projected to increase to 4.6% and 13.6% of the labor force, respectively, to result in a net gain of 10% in the labor force by the year 2035 (Passel & Cohn 2017). Because immigrants and the children of immigrants will contribute to this projected increase in the US labor force, understanding their mental health is important for ensuring a healthy future workforce. Children’s mental health also has important implications for other outcomes across the life course, including adult educational attainment and adult physical and mental health functioning (Case et al. 2005)

OVERVIEW

The term children of immigrants encompasses a great deal of complexity and diversity. Children of immigrants may be immigrants themselves or may have been born in the United States to foreign-born parents (Hernandez et al. 2011). The first generation refers to foreign-born children who are themselves immigrants; the second generation refers to US-born children with one or more immigrant parents; the third or later generation refers to US-born children with US-born parents (Hernandez et al. 2011). Children of immigrants may come from legal, undocumented, or mixed-status families; in mixed-status families, at least one parent (and perhaps some siblings) may be undocumented, whereas at least one child was born in the United States and is therefore a citizen (Vargas 2015). Children of immigrants may have parents residing in the United States, have come to the United States as unaccompanied minors (Huemer et al. 2009), or be part of transnational families in which parents and children live in different countries but maintain close ties (Dreby & Adkins 2012). Because the focus of the extant literature has been on children with foreign-born parents who are living in the United States, this review focuses on children of Asian and Latino descent within this group. Although international migration is not the focus of this review, we recognize that migration is a worldwide phenomenon (Connor & Lopez 2016) that is accompanied by a growing literature on immigrants and children of immigrants who live in Europe and other countries.

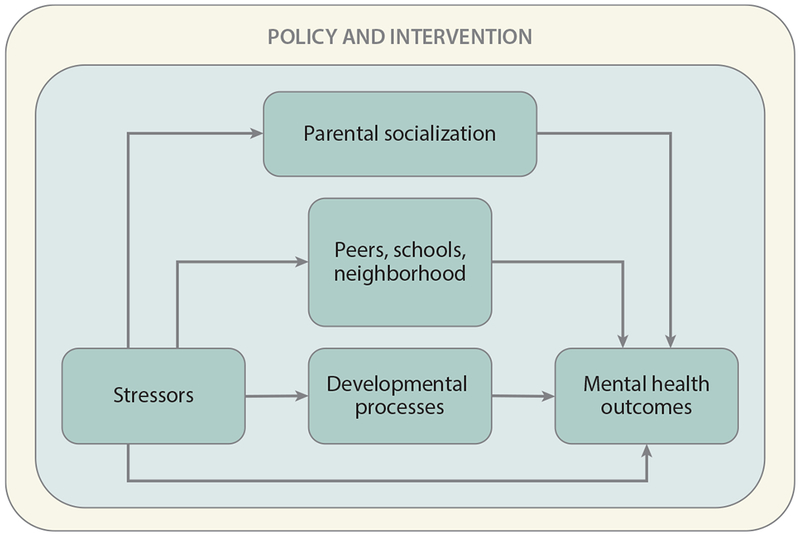

The framework guiding this review (Figure 1) considers both transcultural and culture-specific factors that can be considered stressors. Transcultural stressors can affect any social group, regardless of culture or nativity. Culture-specific stressors are more relevant for minorities and children of immigrants in the United States. We posit that these transcultural and culture-specific stressors can have a direct, interactive, or indirect impact on the mental health of children of immigrants through parental socialization, peers, schools, neighborhoods, and developmental processes. With an empirical understanding of these processes, policies and interventions can be implemented to improve the mental health of children of immigrants.

Figure 1.

Model of mental health outcomes in children of immigrants.

Our review also focuses on adolescence, parental socialization, and two developmental processes shaping the experience of adolescents from immigrant families, namely bilingualism (Bialystok 2001) and ethnic identity (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014b). We focus more on parental socialization and developmental processes because empirical, evidence-based interventions targeting these processes are associated with positive mental health outcomes in children of immigrants (Bacallao & Smokowski 2005, Gonzales et al. 2012, Lau et al. 2011, Pantin et al. 2003, Umaña-Taylor et al. 2017). We also recognize that child characteristics and additional proximal and distal factors (e.g., peers, schools, and neighborhoods) can have a profound influence on the mental health of children of immigrants (Garcia Coll et al. 1996). With some exceptions (e.g., Kia-Keating & Ellis 2007), there are fewer empirical, evidence-based interventions targeting these other factors. However, we do reference studies of these other factors when they are relevant to the focus of our review.

To understand the mental health of children of immigrants of Asian and Latino descent, we use three theoretical perspectives: two that recognize the culture-specific experiences of children of immigrants as ethnic minority children (the integrative model of the study of minority children) (Garcia Coll et al. 1996) growing up with foreign-born parents (ecodevelopmental theory) (Ortega et al. 2012, Prado et al. 2010) and one that recognizes transcultural stressors, such as family economic stress, that may disproportionally affect immigrant families (Conger & Conger 2002, White et al. 2009). The integrative model of minority child development (Garcia Coll et al. 1996) emphasizes the central role of discrimination as a stressor among ethnic minorities that can undermine resources and opportunities, and recognizes that families of minority children create adaptive practices in response to stressors to develop competence in their children. Complementing this view within the framework of immigrant families is ecodevelopmental theory (Ortega et al. 2012, Prado et al. 2010), which recognizes the central role of the parent–child acculturation gap, or the cultural challenge of orienting toward the heritage and destination cultures at different rates, as a stressor that has downstream effects on social relationships, such as family and peer relationships, that influence child mental health. In contrast, family stress theory is a transcultural theory. Family economic stress is posited, in family stress theory, to be a key stressor that impairs marital and parent–child relationships and compromises children’s mental health (Conger & Conger 2002). Our framework therefore includes both culture-specific and transcultural stressors and examines how they may work in conjunction to influence the mental health of children of immigrants.

This review focuses heavily on adolescence, a critical developmental period defined by major physical, cognitive, and social changes occurring at the same time (Blakemore & Mills 2014). Specifically, the developing adolescent brain triggers changes that carry important implications for cognitive function (e.g., executive function) and render adolescents more sensitive to peer reactions and other environmental cues (Blakemore & Mills 2014). These major changes may explain why the onsets of psychiatric illnesses often occur in adolescence (Kessler et al. 2005). Thus, it is important to examine the key processes that can inform adolescent mental health. In this review, we focus on two key developmental processes among children of immigrants: bilingualism, which exerts important effects on cognitive functioning, and ethnic identity, which helps direct social development for immigrant and minority adolescents. We consider how these developmental processes, along with parental socialization, may confer both risk and protection in terms of adolescents’ mental health outcomes.

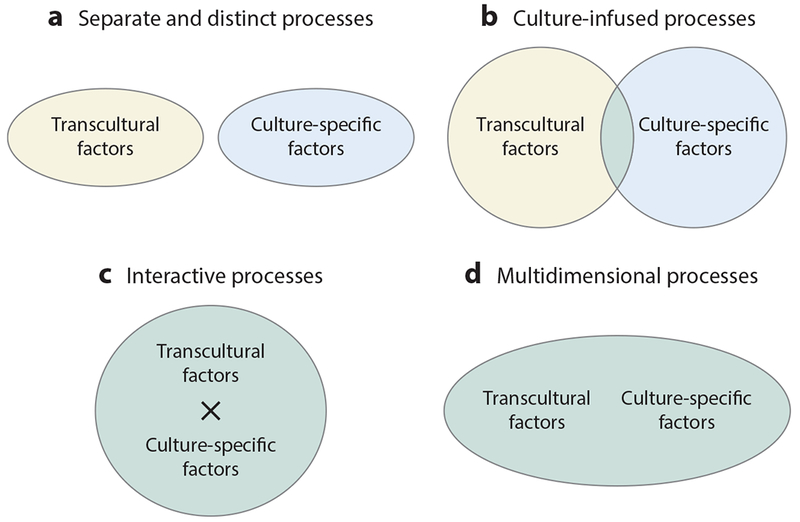

There are at least four ways in which culture-specific and transcultural factors can influence the mental health of children of immigrants (Figure 2). Culture-specific and transcultural factors can make separate and distinct contributions (Figure 2a), fuse to make an independent contribution (Figure 2b), make interactive contributions (Figure 2c), or be represented by multiple dimensions of each factor (Figure 2d) to influence mental health in children of immigrants.

Figure 2.

Processes of interaction between transcultural and culture-specific factors of mental health in children of immigrants. (a) Separate and distinct processes. (b) Culture-infused processes. (c) Interactive processes. (d) Multidimensional processes.

Culture-specific and transcultural factors can make independent contributions, and one factor may be more influential than others when accounting for influence on mental health (Figure 2a). For example, White et al. (2009) found that pressure to speak English (a culture-specific stressor) and economic pressure (a transcultural stressor) additively made independent contributions to depressed mood in a sample of Mexican American parents. However, multiple factors can be considered together, and one factor may emerge as a significant contributor to mental health in children of immigrants. For example, using the Hispanic Stress Inventory, a measure that includes a number of culture-specific factors, Goldbach et al. (2015) found that acculturation gap between parents and children emerged as a culturally significant predictor of alcohol use, after accounting for discrimination, in Latino adolescents.

Culture-specific and transcultural factors can also fuse to influence the mental health of children of immigrants (Figure 2b). In acculturation research, the creation of a new cultural identity that fuses elements of the heritage and destination cultures can result in a cultural orientation that is greater than the sum of its parts (Flannery et al. 2001). For example, a Mexican American child may identify as Mexican, as American, or as Mexican American (a hybrid identity that is more than the sum of its parts). Although a hybrid identity reflecting biculturalism tends to facilitate positive mental health outcomes (Nguyen & Benet-Martínez 2013), children of immigrants may also adopt negative or oppositional cultural identities, such as cholo or la raza (Unger et al. 2014). Specifically, cholo is a term used to describe gang members, and la raza is a cultural identity that represents resistance to discrimination by the dominant group (Unger et al. 2014). Identifying with oppositional cultural labels may promote more risky behaviors, such as substance use (Unger et al. 2014).

Interactions between culture-specific and transcultural factors can also be tracked using the statistical interactions approach in social science research (Aiken & West 1991) to understand the influences of these factors on the mental health of children of immigrants (Figure 2c). For example, for Mexico-born adolescents living in the United States, language hassles (a culture-specific factor) may predict more externalizing symptoms, especially when accompanied by low levels of family cohesion (a transcultural factor) (Nair et al. 2013). Language hassles refer to negative events related to using either the heritage language or the language of the destination country, such as being criticized for speaking Spanish or being put down by a teacher for not speaking English well.

Culture-specific and transcultural factors can also be viewed as multidimensional and used in statistical approaches, such as latent profile analysis (Collins & Lanza 2010), or as latent factors in structural equation modeling (Kline 2016) to understand the mental health of children of immigrants (Figure 2d). For example, both culture-specific dimensions (discrimination and language hassles as stressors) and transcultural dimensions (maternal depression, economic hardship, parent–child conflict, deviant peers, and peer conflict as stressors) were used to conduct latent profile analysis, producing three types of risk profiles in Mexican American adolescents (Zeiders et al. 2013). Adolescents with the highest risk (highest levels of stressors across multiple dimensions) reported the most problematic mental health symptoms (Zeiders et al. 2013). In a structural equation modeling framework, a latent factor comprised of culture-specific factors (perceived discrimination, bicultural stress, and negative context of reception in the destination culture) was found to predispose Latino adolescents toward depressive symptoms, substance use, and aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors (Schwartz et al. 2015b).

Against the backdrop of the theories and methods reviewed above, we highlight the various ways that culture-specific and transcultural stressors directly, interactively, or indirectly influence parental socialization and developmental processes to affect the mental health of children of immigrants. Before doing so, however, we first review the extent of mental health problems in children of immigrants.

PREVALENCE OF MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IN CHILDREN OF IMMIGRANTS

The mental health of immigrants has most often been framed in terms of the immigrant paradox, in which immigrants experience better mental health than their native-born counterparts despite the lower socioeconomic status of immigrants (Marks et al. 2014). This paradox has also been termed the healthy immigrant effect (Castañeda et al. 2015). The assumption is that the most healthy immigrants are selecting themselves to migrate, and unhealthy immigrants are returning to their country of origin (salmon bias) (Arenas et al. 2015), thus making the immigrant pool more healthy overall. At present, though, due to lack of cross-country data, a full and rigorous test of these assumptions has not been fully realized. Moreover, we currently lack a national epidemiological study to ascertain levels of psychiatric diagnoses by nativity for children of immigrants. We therefore use national epidemiological data sets on adults, along with data related to nativity, age of arrival, and years of residence in the United States, to ascertain information relevant for understanding mental health functioning in children of immigrants. We also turn to prominent studies that have sampled adolescents in the United States and have also included an assessment of nativity to make more direct inferences about the mental health of children of immigrants, acknowledging that such studies typically assess mental health functioning in terms of symptoms rather than as psychiatric diagnoses.

Large-scale epidemiological surveys generally support the notion of an immigrant paradox for psychiatric diagnoses among adults, using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) (Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 1994). Using DSM-IV criteria, Breslau et al. (2007) found a health advantage for adult immigrants relative to native-born individuals for various classes of psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Also using DSM-IV criteria, Alegría et al. (2007) and Takeuchi et al. (2007) found that this nativity advantage was replicated in the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) for lifetime prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses (depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders) among Latinos and Asian Americans in the United States.

The age of an immigrants’ arrival can provide information on whether developmental status at the time of migration can influence immigrants’ future mental health. The NCS-R and NLAAS on adults suggest that migration before adolescence puts immigrants at a risk level for psychiatric diagnoses similar to that of native-born individuals, whereas migration as an adult provides a mental health advantage (Alegría et al. 2007, Breslau et al. 2007, Takeuchi et al. 2007).

Acculturation is a construct that is central to understanding the mental health of immigrants (Schwartz et al. 2010). Acculturation refers to the culture change that occurs when immigrants settle in a destination culture. In large epidemiological studies, acculturation is often studied using English fluency or years of residence in the United States as a proxy (Schwartz et al. 2010). Whether acculturation relates to better or worse mental health is unclear, as findings have been generally inconsistent. In the NLAAS, for example, higher English proficiency related to disadvantaged mental health status in Latinos, whereas the pattern was the opposite for Asian American men (Alegría et al. 2007, Takeuchi et al. 2007).

The evidence is also mixed on whether the initial immigrant mental health advantage dissipates over time. The NCS-R showed that the incidence of psychiatric disorders among immigrants increased with longer time spent in the United States, until levels of impulse control, substance use, and mood disorders reached those seen among native-born individuals (Breslau et al. 2007). In contrast, the NLAAS showed no consistent pattern and no significant effect of longer time spent in the United States on psychiatric diagnoses after accounting for age (Alegría et al. 2007, Takeuchi et al. 2007). However, because the NLAAS was conducted in 2002-2003, more recent statistics are needed. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL), conducted between 2008 and 2011, provides more recent data on the mental health of immigrants, but it does not include measures of psychiatric disorders (Perreira et al. 2015). Nonetheless, the HCHS/SOL does find evidence that, among Latinos, there are higher rates of moderate to severe psychological distress, depression, and anxiety with longer exposure to US culture (Perreira et al. 2015).

The national epidemiological studies we review above were based on information provided by adult participants; however, it is also important to examine the rates of mental health problems in child and adolescent populations directly. We anchor our review using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), one of the most prominent national studies of adolescents in the United States. Across studies, there is evidence for both immigrant advantage and disadvantage in internalizing problems, whereas our review on suicidal behaviors, externalizing problems, and substance use generally points to immigrant advantage among children of immigrants.

For internalizing problems, the evidence for immigrant advantage in children of immigrants is mixed. The Add Health study found that the adolescent immigrant health advantage of lower depressive symptoms was initially not apparent but became apparent after accounting for protective factors such as family support and parental supervision (Harker 2001). Another prominent study, the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, found an opposite pattern, in which first- and second-generation Latino children had higher levels of internalizing problems relative to third-generation children, but this disadvantage was no longer significant after accounting for neighborhood characteristics (Lara-Cinisomo et al. 2013). In a review of 35 studies published between the years 2009 and 2013, Kouider et al. (2015) identified children of immigrants in the United States with an Asian background as being particularly at risk for internalizing problems.

For suicidal behavior, the immigrant health advantage is more apparent. The risk of suicide is lower in the first generation and increases in second- and third-generation adolescents in both the Latino and the Asian American samples of Add Health (Duldulao et al. 2009, Peña et al. 2008). Although the risk of suicidal behavior is lower among first-generation children, a review of 18 studies showed that immigrant children were at greater risk of being victims of bullying, peer aggression, and violence; the risk was especially high among those whose heritage language was not English (Pottie et al. 2015).

For externalizing problems and substance use, we again find a consistent pattern: an immigrant advantage that dissipates over time spent living in the United States. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health found evidence of an immigrant health advantage, especially among 15- to 17-year-olds, for externalizing problems such as crime, violence, and drug misuse (Salas-Wright et al. 2016). They also found that later age of arrival and fewer years spent in the United States functioned as protective factors for externalizing problems. Such findings were replicated in two other national studies, for alcohol use among Latinos in Add Health (Bacio et al. 2013) and for substance use in the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (Gfroerer & Tan 2003).

The mental health of undocumented children, unaccompanied minors, and refugee children deserves special mention because of the often traumatic circumstances, such as war, violence, or other natural disasters, that they face both before migration and in their transit to the United States and because of the lack of legal status that can continually undermine children’s mental health. Despite some evidence of first-generation children in the United States having an advantage in terms of their mental health, children who are undocumented, unaccompanied, or refugees are at elevated risk for mental health problems (Takeuchi 2016). Indeed, in a survey of first-generation immigrant adolescents, relative to documented adolescents, undocumented adolescents were at elevated risk for anxiety, and adolescents in mixed-status families showed both greater anxiety and marginally greater risk for depressive symptoms (Potochnick & Perreira 2010). Undocumented parental legal status can be particularly detrimental; for example, relative to those with documented parents, Mexican children in Los Angeles with mothers who were unauthorized showed elevated rates of internalizing and externalizing problems (Landale et al. 2015). Another special case in which children are at higher risk of mental health problems occurs when the family is involuntarily transnational, and children are maintaining contact with parents who lack legal status and have therefore been deported from the United States back to their country of origin (Dreby 2012a).

The number of unaccompanied minors has grown precipitously in the United States in recent years, swelling from 24,000 in 2012 to over 67,000 in 2014; this growth is mostly attributable to the northern triangle consisting of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (Roth & Grace 2015). Unaccompanied minors are often fleeing gang violence in their country of origin and show high rates of mental health problems because of the trauma that they experienced in their country of origin as well as during their journey to the United States (Ciaccia & John 2016). Refugee children also show high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder, both on arrival and in the United States postmigration, due to the continuing acculturative stressors they face (Lincoln et al. 2016).

Studies on the mental health of immigrants often argue that accounting for stressors, such as the discrimination facing immigrants, may explain nativity differences found in mental health (e.g., Lau et al. 2013, Perreira et al. 2015). It is therefore important to understand the predictors, mechanisms, and conditions through which such stressors affect the mental health of children of immigrants. In the next section, we review how both culture-specific and transcultural stressors influence the mental health of children of immigrants.

TRANSCULTURAL AND CULTURE-SPECIFIC STRESSORS

Children of immigrants experience both transcultural stressors and culture-specific stressors related to their minority and immigrant status; both types of stressors influence their mental health. Although transcultural stressors, such as economic stressors and neighborhood disadvantage, are not unique to children of immigrants, this population may be more likely to experience them due to disadvantages associated with being a member of an ethnic minority group and/or the immigrant status of their parents. For example, for immigrant parents with limited income, education, and English skills, the most viable housing options may be in low-rent neighborhoods with high crime rates (Pumariega et al. 2005). We therefore highlight two stressors, economic pressure (Mistry et al. 2009) and neighborhood disadvantage (White et al. 2016), as transcultural stressors that influence the mental health of children of immigrants.

There are also culture-specific stressors that may be unique to children of immigrants; these include stressors experienced prior to migration and during transit to their destination (Drachman 1992). Once in the United States, regardless of whether they are first or second generation, children of immigrants may experience a range of acculturative stressors. Acculturative stressors have been conceptualized to include a multitude of factors, including perceived discrimination and cultural conflicts (Gil et al. 2000). One of the most unhealthy stressors is discrimination (Armenta et al. 2013, Garcia Coll et al. 1996, Lewis et al. 2015), and its effects on the mental health of children of immigrants can vary by source, timing, and context. In the process of resettlement, acculturative stressors can influence the mental health of children of immigrants whether these stressors are experienced by the children themselves or by their parents.

Transcultural Stressors

Transcultural stressors, such as economic pressure and neighborhood disadvantage, have been shown to have both direct and indirect links to adolescent mental health among Asian and Latino children of immigrants. Gonzales et al. (2011) and White et al. (2015) extended family stress theory’s (Conger & Conger 2002) focus on economic stress to include neighborhood disadvantage as an environmental stressor facing Mexican American families. They found that both economic stress and neighborhood disadvantage undermined maternal warm parenting and/or increased harsh parenting, which, in turn, led to more externalizing problems in Mexican American adolescents (Gonzales et al. 2011, White et al. 2015). Consistent with Garcia Coll et al.’s (1996) notion of adaptive cultures in minority and immigrant families, White et al. (2015) identified familism (reciprocity among family members) as an adaptive resilience factor that would be valuable to retain and promote in Mexican American mothers, as mothers with high levels of familism were protected from disruptions that link economic stress with low levels of warm parenting.

Family stress theory (Conger & Conger 2002) is also supported by research on Chinese American families. There is evidence of an indirect process from parent reports of economic stress to Chinese American adolescent mental health. Parent reports of economic stress (making financial adjustments, economic strain, and difficulty making ends meet) indirectly led to Chinese American adolescent depressive symptoms through adolescent reports of economic stress and financial constraints (Mistry et al. 2009). There is also evidence that a greater degree of neighborhood disadvantage leads to erosion of positive parenting practices, such as maternal monitoring in Chinese Americans (Liu et al. 2009). However, the indirect pathway was different, as neighborhood economic disadvantage related to externalizing problems in Chinese American children, which in turn led to erosion of positive parenting (Lee et al. 2014).

Culture-Specific Stressors

Culture-specific stressors related to the context of exit (premigration and during migration) to the United States have been studied in reference mostly to refugees and unaccompanied minors (Pumariega et al. 2005). Traumatic experiences in the country of origin (e.g., war, trauma, violence, famine) can prompt children to make the journey to the United States, and the journey itself can be traumatic (e.g., crossing rivers, witnessing deaths, and experiencing physical violence or sexual exploitation) (Chan et al. 2009, Pumariega et al. 2005). The transit is often undertaken without caregivers and can also entail detention or asylum hearings that can take 2 years or longer (Lustig et al. 2004). Upon arrival, postmigration stressors, including experiences of discrimination and other acculturative stressors, ensue (Ellis et al. 2010). Of course, these stressors are not limited to refugees and unaccompanied minors—they are relevant to children of immigrants more generally.

Discrimination.

One of the most prominent culture-specific stressors relevant to the mental health of children of immigrants is discrimination (Berry et al. 2006, Garcia Coll et al. 1996). Studies vary in the way discrimination is assessed, and they may include everyday discrimination as a measure of overall mistreatment (Lewis et al. 2015), discrimination based on one’s race or ethnicity (Greene et al. 2006), or discrimination based on an assumption that children of immigrants are all foreigners even if they are born in the United States (Armenta et al. 2013). Of these three types of discrimination, everyday and racial discrimination are the two that are most likely to be measured in studies of children of immigrants, with fewer studies focusing on foreigner stereotype. Regardless of the type of measure used, discrimination experiences are significantly linked to mental health problems (Lewis et al. 2015, Pascoe & Smart Richman 2009) and to substance use in children of immigrants (Unger et al. 2014). In this section, we review studies of children of immigrants to demonstrate the importance of considering the source, timing, and context of discrimination experiences and their links to mental health.

The sources of discrimination experiences can vary: Adolescents may experience discrimination from peers or adults, or they may experience discrimination vicariously through their parents’ experiences, either of which can influence their mental health. Differential experiences of peer versus adult discrimination were demonstrated by Greene et al. (2006). Using a sample of high school students that included Asian and Latino children of immigrants, they found an increase in perceptions of discrimination coming from adults during high school, whereas perceptions of discrimination coming from peers remained stable. In addition, Rosenbloom & Way (2004) found that, when adolescents are members of an ethnic group that is more likely to be foreign-born at their high school (Chinese Americans and Dominicans, in their study), they report higher levels of peer or adult discrimination depending on their ethnic group membership. Specifically, Chinese American adolescents are more likely to experience peer discrimination and Dominican adolescents more likely to experience adult discrimination (Rosenbloom & Way 2004). Both peer and adult discrimination led to increases in depressive symptoms over time in children of immigrants (Greene et al. 2006).

There is also evidence that parental experiences of discrimination influence the mental health of children of immigrants. The intergenerational transmission of parents’ discrimination experiences can have an indirect influence on adolescent mental health through erosion of family processes. Hou et al. (2017) demonstrated an indirect process in Chinese American families, in which paternal experiences of discrimination led to adolescent delinquency and depressive symptoms via increased paternal depressive symptoms and maternal hostility toward adolescents. The intergenerational transmission of parents’ discrimination experiences can also be interactive with other family members. Specifically, Crouteretal. (2006) found that Mexican-origin fathers’experiences of workplace racism led to more depressive symptoms among family members, including the child’s depressive symptoms, when mothers were low in acculturation toward US culture (Crouter et al. 2006). Taken together, these studies highlight the important role of fathers’ discriminatory experiences and their intergenerational influence on the mental health of children of immigrants.

The timing of discrimination experiences is another important consideration for the mental health of children of immigrants. Although the pernicious effect of discrimination on mental health is often considered to be a contemporaneous process, its long-term implications can go beyond mental health to influence academic outcomes, as well. Specifically, Benner & Kim (2009a) found that contemporaneous experiences of discrimination were more likely to relate to depressive symptoms, whereas early discrimination experiences were more likely to relate to worse later academic outcomes, in Chinese American adolescents. Corroborating this finding, another study that sampled Asian and Latino children of immigrants found that high school discrimination experiences related to later academic outcomes, specifically college persistence (Witkow et al. 2015).

The context of discrimination experiences is also important to consider. The literature on this topic considers the ways in which discrimination interacts with health behaviors, the multiple influences of discrimination in combination with other psychosocial experiences, and resources for coping with discrimination experiences. For example, Yip (2015) found that high levels of discrimination, coupled with poor sleep (health behavior), predicted increases in depressive symptoms in a sample that included children of immigrants. In addition, a host of psychosocial experiences, including discrimination, can work in conjunction with one another to influence the mental health of children of immigrants. Lorenzo-Blanco et al. (2016) found that Latino adolescents that belonged to a profile characterized by a high level of ethnic discrimination, high bullying victimization, and few positive experiences in social support and perceived school safety were at the highest risk of depressive symptoms and smoking (Lorenzo-Blanco et al. 2016). On a more positive note, adolescents can cope with discrimination by seeking out family support. Specifically, discrimination’s link to externalizing problems in Mexican American adolescents was weaker among individuals with high levels of family support (Park et al. 2017). Together, these studies suggest that the context of discrimination experiences can either exacerbate or mitigate the link between discrimination and poorer mental health in children of immigrants.

In studying the discrimination experiences of children of immigrants, another relevant factor to consider is stress related to being perceived as a foreigner. Asian and Latino children of immigrants in the United States may consider themselves to be just as American as their European American counterparts but may be more likely to be stereotyped as foreigners because of their physical appearance and minority background (Armenta et al. 2013). Armenta et al. (2013) found a direct link between being perceived as a foreigner and lower life satisfaction and more depressive symptoms, particularly among US-born Asians and Latinos, even after accounting for ethnic discrimination. Kim et al. (2011) found an indirect pathway that predicted being perceived as a foreigner, through which self-reported low levels of English fluency led to reports of speaking English with an accent, which then led to being perceived as a foreigner. Being perceived as a foreigner led to more discrimination experiences and, in turn, to more depressive symptoms in Chinese American adolescents. These studies underscore the need to recognize that foreigner discrimination plays a role in the mental health of children of immigrants.

Acculturative stressors.

Acculturation is a multidimensional process involving heritage culture and destination culture values, practices, and identifications (Schwartz et al. 2010). In the process of adjusting to a new culture, acculturative stressors can arise. Acculturative stress chiefly involves language difficulties and the conflicts that occur when balancing between one’s heritage and destination cultural orientations (Torres et al. 2012). In this section, we present studies that examine acculturative stressors, as experienced by adolescents and their parents, and their role in the mental health of children of immigrants.

Romero & Roberts (2003) conceptualize acculturative stress as bicultural stress in children of immigrants, or the pressure to adhere to both heritage and US cultures. Bicultural stress is a proximate life stressor that affects bilingual and bicultural youth in school, peer, and family contexts (Romero & Roberts 2003). Bicultural stress is composed of family stressors (e.g., family conflict related to family traditions), discrimination stressors (e.g., worry about immigration), monolingual stressors (e.g., problems with poor English), and peer stressors (e.g., not feeling accepted because of ethnicity) (Romero & Roberts 2003). Romero & Roberts (2003) found that US-born youths were more likely to report stress related to needing to speak better Spanish, whereas immigrant youths reported more stress regarding needing to be more proficient in English in school. As expected, a higher level of bicultural stress was related to more risk behaviors and depressive symptoms in both US-born and immigrant adolescents (Romero & Roberts 2003, Romero et al. 2007).

In the current US political climate, which is characterized by high anti-immigrant sentiment, the perception of hostility from the receiving community is another source of acculturative stress facing children of immigrants (Schwartz et al. 2014). Even after accounting for ethnic discrimination, a negative context of reception predicted more depressive symptoms in Latino adolescents (Schwartz et al. 2014).

Acculturative stress as experienced by parents can also indirectly influence the mental health of children of immigrants. For example, in Chinese American families, Hou et al. (2016) found that parental acculturative stressors, as represented by both bicultural management difficulty (challenges related to balancing between heritage and destination cultural orientations) and perpetual foreigner stress, led to interparental conflict, parent–child conflicts, and adolescents’ sense of alienation from their parents. In turn, these factors led to more adolescent depressive symptoms, more delinquent behaviors, and lower academic performance.

Together, the studies reviewed above suggest that the risks associated with both transcultural and culture-specific stressors work in isolation or together as multiple risk factors affecting the mental health of children of Asian and Latino immigrants. These studies also consistently emphasize the role of parental support in mitigating the negative effects of stressors on the mental health of children of immigrants (Juang & Alvarez 2010, Trentacosta et al. 2016). In the next section, we present studies on parental socialization patterns in children of Asian and Latino immigrants and discuss how parenting behaviors (e.g., parenting, ethnic–racial socialization) and parent–child relationships as influenced by acculturation (e.g., acculturation gap, language brokering) both function as forms of risk and protection for children of immigrants.

PARENTAL SOCIALIZATION

Parental socialization traditionally encompasses general parenting behaviors, such as parenting styles (Darling & Steinberg 1993). For Asian and Latino immigrant parents, it can also include teaching children about what it means to be an ethnic minority through ethnic–racial socialization (Hughes et al. 2006, Juang et al. 2016). For children in immigrant families, parental socialization is also influenced by acculturation. The parent–child acculturation gap refers to potentially discrepant acculturation levels between parents and children. This gap can result in language brokering, whereby children translate between the heritage language and English for their English-limited parents. Together, these parental socialization practices and parent–child relationships, as influenced by acculturation, have direct, interactive, and indirect effects, as well as promotive and inhibiting effects, on the mental health of children of immigrants.

Parenting

Parental socialization of children is typically studied by identifying parenting styles, which are composed of parenting practices (Darling & Steinberg 1993). The two most commonly studied styles are authoritative and authoritarian parenting, with authoritative parenting generally relating to positive mental health outcomes and authoritarian parenting generally relating to more negative mental health outcomes in children (Darling & Steinberg 1993). Because these effects are not as robust for Asian and Latino children of immigrants as they are for European American children (Calzada et al. 2012, Chao 1994), more recent scholarship has called for the consideration of the role of cultural values in understanding parenting behaviors and in identifying parenting styles that may be unique to these groups. For example, in Chinese American families, supportive parenting, which resembles authoritative parenting, is distinguished by high levels of positive (e.g., warmth, monitoring) and low levels of negative (e.g., hostility) parenting, as well as a moderate level of shaming, a culturally informed parenting behavior (Kim et al. 2013b). Similarly, in Mexican American parents, cultural values of respeto (respect for authority) and familism (reciprocity among family members) relate to authoritative parenting (White etal.2013). There is also evidence of parenting styles that are unique to each group. In Chinese Americans, tiger parenting is characterized by high levels of shaming along with high levels of both positive and negative parenting (Kim et al. 2013b). For Mexican American families with adolescents, White et al. (2013) found no-nonsense parenting to be a unique parenting style characterized by moderate levels of harsh parenting with elements of authoritative parenting (high levels of both responsiveness and demandingness).

These unique parenting profiles may represent adaptive parenting strategies in response to the environmental demands of living as ethnic minorities and as immigrants (Garcia Coll et al. 1996). According to Sue & Okazaki (1990), Asian Americans see academic achievement as a form of relative functionalism. That is, achieving academically is seen as an important avenue to achieving upward mobility. For this reason, Chinese American parents may adopt a parenting strategy such as tiger parenting with the goal of high academic achievement for their adolescents (Kim et al. 2013b). Such a strategy, however, often results in adolescents who are paradoxically adjusted (high levels of academic achievement, low levels of mental health) (Kim et al. 2015). Therefore, although tiger parenting can result in high academic achievement for adolescents, this may come at the cost of their mental health. For Mexican American families, White et al. (2016) found that, for those living in high-adversity neighborhoods, no-nonsense parenting is an adaptive strategy for fathers. This type of parenting allows fathers to recognize the environmental demands of their neighborhoods and adapt their parenting accordingly, resulting in declines in internalizing problems across the course of adolescence in their children. Studies of parenting among the families of Mexican American and Chinese American adolescents highlight the importance of going beyond transcultural parenting dimensions to consider culture-specific dimensions (such as shaming in Chinese Americans) and contextual demands (such as high-adversity neighborhoods) to understand adaptive parenting among Asian and Latino immigrant parents.

Ethnic–Racial Socialization

Asian and Latino immigrant parents also socialize their children about race, culture, and ethnicity (Hughes et al. 2006, Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014a). Ethnic–racial socialization encompasses multiple domains. In immigrant families, parents’ discriminatory experiences serve as a catalyst for initiating discussions about racial bias or practicing racial socialization with their children (Benner & Kim 2009b). We focus on two of the more widely studied of these domains: ethnic and cultural socialization, where parents teach their children about their heritage and history, pass on customs, and promote ethnic pride (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014a); and preparation for bias, where parents teach their children about how to be aware of and cope with discrimination (Hughes et al. 2006) (see the sidebar titled Ethnic–Racial Socialization in Asian Children of Immigrants).

In both Asian and Latino children of immigrants, ethnic and cultural socialization relates to better mental health. Mechanisms underlying the positive effect of ethnic and cultural socialization include engendering a stronger sense of ethnic identity and instilling a sense of optimism, ultimately predicting positive mental health in adolescents (Gartner et al. 2014, Liu & Lau 2013, Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014a). On the other hand, preparation for bias relates to negative mental health outcomes in children of Asian and Latino immigrants. Mechanisms underlying the negative effect of preparation for bias can include negative perceptions of one’s ethnic group, especially when accompanied by perceptions of adult discrimination, feeling like a misfit, and higher levels of pessimism, ultimately relating to more depressive symptoms in adolescents (Benner & Kim 2009b, Liu & Lau 2013, Rivas-Drake et al. 2009). However, there is also evidence that preparation for bias can relate to a stronger sense of ethnic identity in Asian and Latino adolescents (Hughes et al. 2009), suggesting the need for additional research to untangle the conditions under which preparation for bias can relate to a positive versus a negative sense of ethnic identity and to predict mental health outcomes.

Parent–Child Acculturation Gap

According to ecodevelopmental theory (Prado et al. 2010), an acculturation gap is a hallmark of immigrant families that affects developmental outcomes among children of immigrants. Acculturation gap refers to a mismatch in levels of cultural orientation to the heritage and destination cultures between parents and children in immigrant families (Telzer 2011). A meta-analysis finds that, among children of Asian and Latino immigrants, acculturation gap can have deleterious effects on mental health, particularly in the US-born second generation (Lui 2015). The findings on acculturation gap and mental health outcomes, which we review below, are complex and nuanced: Some types of acculturation gap show protective effects, whereas other types seem to be risk factors for mental health problems.

The longstanding acculturation gap–distress model proposes that high levels of parent–child acculturation discrepancy represent a risk factor for poor mental health in children (Kim et al. 2013a, Schofield et al. 2008). This model suggests that parent–child acculturation discrepancies erode the quality of family relationships and predict child mental health problems. For example, higher levels of father–child acculturation gap were related to more externalizing problems in Mexican American adolescents, especially when the father–adolescent relationship quality was poor (Schofield et al. 2008). Moreover, in Chinese American families, higher levels of father–child acculturation gap, particularly in orientation toward US culture, is detrimental in that it predicts parents’ lower use of warmth, monitoring, and reasoning with their adolescents and increases adolescents’ sense of alienation from parents, resulting in more adolescent depressive symptoms (Kim et al. 2013a). In Latino families, though, it is the discrepancy in heritage orientation, where adolescents endorse Latino cultural values, practices, and identity less than their parents do, that puts them at risk of poor family functioning and poor mental health (Schwartz et al. 2016).

Weaver & Kim (2008) identified a specific type of parent–child acculturation gap that relates to risk for poor family functioning and mental health in Chinese Americans. They described three profiles of acculturation in a Chinese American sample (bicultural, more American, and more Chinese). Relative to other combinations, parent–child dyads with an acculturation match—specifically, bicultural adolescents with bicultural parents—reported more supportive parenting, which then led to fewer adolescent depressive symptoms. Consistent with the acculturation gap–distress model, adolescents with an acculturation mismatch (or acculturation gap)—specifically, American-oriented adolescents with Chinese-oriented parents—reported the least supportive parenting and the most depressive symptoms.

Lau et al. (2005) identified a different type of acculturation gap that related to mental health functioning in Mexican Americans. An acculturation gap in the unexpected direction, such that adolescents are more oriented toward the heritage culture than their parents are, was associated with more conduct problems, whereas an acculturation gap in the expected direction (adolescents more oriented to the destination culture than the parents) did not lead to the expected positive relationship to family conflict and conduct problems. In fact, Telzer (2011) contends that the expected acculturation gap between parents and children (where children are more oriented to the destination culture than their parents are) is considered normative, as it allows children to facilitate immigrant families’ adjustment to the cultural values and customs of the destination society. Consistent with this view, Schwartz et al. (2016) found that parent–child gaps in the individualist values of US culture were actually predictive of positive functioning and positive mental health outcomes in Latino children.

Language Brokering

Children may assist in the resettlement process of their immigrant families by functioning as language brokers. Language brokers are children who translate, both linguistically and culturally, for their English-limited parents, thereby playing an important role as intermediaries between their parents and the larger society (Kim et al. 2017). Language brokering is a common activity performed by 71-89% of children in immigrant families (Chao 2006).

Language brokering can have both positive and negative consequences for adolescent mental health. When adolescents perceive their language brokering experience as a burden, this stressor may predict more depressive symptoms in Chinese American adolescents (Kim et al. 2014) and more substance use in Mexican American adolescents (Kam & Lazarevic 2014) through increased family-based acculturation stressors. However, language brokering can also be protective, especially in the presence of risk. Specifically, Mexican American adolescents who appraise their language brokering experience as more efficacious are less likely to experience depressive symptoms when they are more at risk (i.e., when they have a high sense of alienation with regard to their parents or a low sense of personal resilience) (Kim et al. 2017).

There is also evidence that the configuration of language brokering experiences matters in predicting positive or negative consequences on adolescent mental health. Kam et al. (2017) identified three types of Latino adolescent language brokers: infrequent–ambivalents (least likely to language broker, with low positive and negative feelings about language brokering and low levels of parentification, which refers to parents relying on their children), occasional–moderates (moderate language brokering with moderate positive and low negative feelings about language brokering and low levels of parentification), and parentified–endorsers (most likely to language broker, with high positive and low negative feelings about language brokering and high levels of parentification). Kam et al. found that occasional–moderates showed the most positive outcomes, as this profile membership did not predict discrimination, depressive symptoms, or risky behaviors. Parentified–endorsers were most at risk for discrimination and depressive symptoms, while infrequent–ambivalents were less engaged in risky behaviors (Kam et al. 2017). These results suggest that assessing the context in which language brokering occurs may be more important than simply assessing the feelings surrounding it to understand its protective and risk functions in children of immigrants.

DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESSES

Children of Asian and Latino immigrants are likely to be exposed to a heritage language other than English at home, and a body of research has identified a bilingual advantage for these children, as well as development processes, such as ethnic identity, that can be a source of both risk and protection in terms of the mental health of children of immigrants.

The term bilingual advantage refers to cognitive advantages that come with being proficient in two or more languages (Bialystok 2015). Bilingualism comes with some costs, such as smaller receptive vocabulary (Luk & Bialystok 2013). However, bilingualism generally confers advantages across the life span when it comes to nonverbal executive functioning cognitive tasks, such as superior performance in working memory and sometimes in inhibitory control relative to mono-linguals (Bialystok 2011, Luk & Bialystok 2013). Studies with adults indicate that being bilingual is associated with better physical and mental health relative to those who are proficient only in English or proficient only in the heritage language (Schachter et al. 2012). The positive effect of bilingualism on mental health can be partially explained by socioeconomic status and family support but not by acculturation, discrimination, or health behaviors (Schachter et al. 2012). Studies with children also demonstrate a bilingual advantage for mental health. Relative to monolinguals, who show faster growth in problem behaviors, Asian bilingual children of immigrants show low levels of growth in externalizing and internalizing behaviors over time (Han & Huang 2010).

A central developmental task of adolescence is developing a sense of identity. Research on identity in children of Asian and Latino immigrants in the United States has largely focused on the role of ethnic identity in their mental health. A strong sense of ethnic identity among children of immigrants is generally considered to be a protective factor for adolescent mental health. Ethnic identity affect (positive feelings about one’s ethnicity), in particular, is linked with robust positive effects on a range of mental health outcomes (e.g., depressive symptoms, internalizing and externalizing problems) among children of immigrants (Neblett et al. 2012, Rivas-Drake et al. 2014). However, there is some research indicating that there exist conditions under which ethnic identity may also function as a risk factor. In fact, a stressor such as discrimination relates to more delinquent behaviors, and this relationship can be exacerbated or mitigated depending on the dimension of ethnic identity under examination. In a sample that included low-income Latino boys, Williams et al. (2014) found that, when adolescents are faced with discrimination, high ethnic identity affirmation (sense of belonging to one’s ethnic group) can be a protective factor, as it does not relate significantly to delinquency, whereas low ethnic identity affirmation is significantly related to delinquency. However, ethnic identity achievement (exploring and committing to one’s ethnic identity) can be a risk factor exacerbating the link between discrimination and delinquency (Williams et al. 2014).

One construct related to ethnic identity in children of Asian and Latino immigrants is bicultural identity integration, which refers to the degree to which individuals living in a bicultural setting perceive their two cultural identities as compatible rather than as oppositional (Benet-Martínez & Haritatos 2005). Bicultural identity integration relates to positive mental health (Chen et al. 2008) and positive youth development (self-esteem, optimism, prosocial behaviors, parental involvement, parent–adolescent communication, and family communication) (Schwartz et al. 2015a) in both Asians and Latinos (see the sidebar titled The Role of Physiology in the Mental Health of Children of Immigrants).

EVIDENCE-BASED INTERVENTIONS FOR CHILDREN OF IMMIGRANTS

The studies reviewed above highlight the risk and protective factors that can impact the mental health of children of immigrants. Identification of such factors is important, as they can represent key program components in interventions. In this section, we highlight various types of evidence-based intervention programs (family-based interventions, a developmentally focused intervention on ethnic identity, and an intervention specific to refugee children) that show efficacy in reducing mental health problems in children of immigrants.

Examples of efficacious family-based interventions have core program components that are culture specific or are both culture specific and transcultural. Entre Dos Mundos is a culture-specific bicultural skills training program designed for Latino adolescents and parents. The program focuses on mediating the negative impact of parent–child conflict and perceived discrimination while increasing familism and biculturalism in parents and adolescents (Bacallao & Smokowski 2005). Attending more sessions was predictive of fewer externalizing problems, such as child aggression and oppositional defiant disorder, along with gains in family adaptability and bicultural identity integration (Smokowski & Bacallao 2009). Familias Unidas is another family-based intervention program that includes culture-specific components such as educating parents about US culture and biculturalism (Pantin et al. 2003). The program also includes transcultural elements, such as increasing communication and negotiation skills to reduce family conflict and distance and fostering connections between the family and other important systems, such as peers and schools, to improve Latino parents’ investment in their adolescents’ lives (Pantin et al. 2003). Program effects indicate increases in parental investment and decreases in adolescent problem behaviors, although there were no significant program effects for school achievement (Pantin et al. 2003).

Examples of efficacious family-based interventions can also have core program components that are more transcultural in focus, but with culturally responsive adaptations. Parent Training (PT) is a program for high-risk Chinese immigrant parents that augments content by addressing the cultural challenges facing these parents (Lau et al. 2011). Sessions target a transcultural component, namely improving multiple parenting skills (e.g., logical consequences, cognitive restructuring, communication training, positive and proactive parental involvement) (Lau et al. 2011). Examples of cultural adaptations in these sessions would be group leaders eliciting parental views on potential cultural and practical barriers to implementing the skills being taught in the sessions or facilitating a discussion with parents about the identified barriers and how the skills being taught can achieve parenting goals. PT has been shown to be effective in reducing negative discipline and increasing positive parenting in Chinese American families and in reducing externalizing and internalizing problems in Chinese American children (Lau et al. 2011).

Another family-based intervention, Bridges, has core program components that are transcultural and is also culturally responsive to Mexican American families (Gonzales et al. 2014). The program has three components: parent sessions (emphasizing effective parenting practices), adolescent sessions (emphasizing coping efficacy), and family sessions (emphasizing family cohesion). It is culturally responsive because its core program components were adapted to recognize the processes more germane to low-income Mexican American families. For example, given that low-income Mexican American parents may have a poor understanding of US schools and may be less prepared to monitor their children’s academic challenges, parenting sessions emphasize positive parenting practices, such as monitoring of schoolwork (Gonzales et al. 2014). Bridges is delivered in middle school and has been shown to be effective in increasing school engagement as a primary mediating mechanism to reduce internalizing symptoms, substance use, and school dropout (Gonzales et al. 2014).

The Identity Project is an evidence-based identity intervention that focuses on increasing adolescents’ identity exploration and resolution, based on empirical evidence for the positive impact of ethnic identity on adolescent mental health (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2017). It is designed as an 8-week intervention for delivery in a school-based setting. Initial results indicate that increasing exploration of adolescents’ ethnic identity improves ethnic identity resolution for youths in the treatment condition. Because ethnic identity resolution can relate to positive mental health, the initial results of this intervention suggest that it shows promise as an evidence-based intervention to reduce mental health problems in children of immigrants.

Because refugees are a special population, we also highlight an intervention that may specifically reduce mental health problems in children in this population. Project SHIFA (Supporting the Health of Immigrant Families and Adolescents) is a multitiered intervention program for Somali refugee youth. It has three main components: resilience building in the community, school-based intervention for those at risk, and direct trauma therapy for those reporting significant levels of psychological distress (Ellis et al. 2013). Program results showed effectiveness in reducing symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among refugee adolescents.

POLICIES FOR CHILDREN OF IMMIGRANTS

Government policies and programs are one way to reduce mental health problems in children of immigrants. Programs such as Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) provide important financial, health, and nutritional assistance for low-income families in the United States (Perreira et al. 2012). Despite their greater need for these services, low-income immigrant families have less access to these programs because of strict eligibility requirements and barriers that result in lower usage of these benefits (Perreira et al. 2012). These barriers include the complexity of the application and eligibility rules, administrative burdens, language and cultural barriers, transportation and other logistical issues, and fear and mistrust of government authorities (Perreira et al. 2012). Moreover, although many children in immigrant families are US-born and are thus eligible for government services, many do not access them, especially when parents are undocumented (Torres & Young 2016). In addition, increased risk of deportation can decrease use of public services such as Medicaid (Vargas 2015).

Lack of legal status is a major obstacle to being eligible for government programs. Government policies such as the 2012 Deferred Action for Child Arrivals (DACA), which provided temporary relief from deportation and renewable work permits for undocumented children of immigrants, have shown positive consequences for mental health (Venkataramani et al. 2017). Specifically, relative to DACA-ineligible individuals, those who were DACA eligible showed lower levels of psychological distress (Venkataramani et al. 2017). For this reason, it is important to implement programs such as DACA to improve the mental health of children of immigrants in the future.

Despite some favorable government policies (e.g., DACA) for undocumented children in the United States, between 2003 and 2013, over 3.7 million immigrants were deported from the United States (Koball et al. 2015). The majority (91%) of these deportees were men, and up to 25% were parents of US-born children (Koball et al. 2015). Deportation of undocumented immigrant parents can have disastrous consequences for families. For example, children may be left in foster care, mothers may become single parents if fathers are deported, parents may lose custody of their US-born children, children may begin to fear law enforcement, children may begin to view being an immigrant as the same as being illegal, and children may begin to associate their immigrant and heritage background with stigma (Dreby 2012b). Among other recommendations, government policies to improve access to benefits, better coordination with child welfare caseworkers, and short-term financial assistance are useful strategies for improving the lives of families affected by the deportation of a family member (Koball et al. 2015).

Unaccompanied minors, in particular, are a group of undocumented immigrant children who have received recent media attention. The peak of arrivals of unaccompanied minors to the United States occurred in 2014, with the largest number coming from Honduras, followed by Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico. These children are often apprehended and detained at the border (Am. Immigr. Counc. 2015). The Office of Refugee Resettlement, an agency of the US Department of Health and Human Services, is then responsible for finding them shelter and directing their legal proceedings (Pierce 2015). The vast majority of unaccompanied minors stay with a parent, relative, or friend in the United States while awaiting the settlement of their cases in the US immigration courts (Pierce 2015). The length of the process, which can take years, means that unaccompanied minors become further integrated into the United States while awaiting the results of their court proceedings. Typically, after their cases are heard, 97% of unaccompanied minors remain unauthorized (Pierce 2015). They may be given informal relief but not legal status in the United States, which means they have limited access to social programs. Given the strong link between undocumented status and poor mental health (Potochnick & Perreira 2010), providing a better avenue for achieving legal status may go a long way toward improving the mental health of unaccompanied minors.

CONCLUSION

The United States is a country founded by immigrants and is expected to increase its immigrant population, from today’s 14% of the US population to 18% in 2065. In fact, immigrants and their children are projected to comprise 36% of the US population in 2065 (Pew Res. Cent. 2015). With these future trends in mind, we have reviewed the ways in which transcultural and culture-specific stressors, parental socialization, and developmental processes influence the mental health of children of immigrants. We have also identified risk factors that can be reduced, and protective factors that can be promoted, to improve the mental health of children of immigrants. Given the many obstacles immigrants and their children face, implementing the evidence-based interventions and policies identified in this review would go a long way toward bolstering the mental health of a growing population, specifically children of immigrants, who represent a large proportion of the US population and our future workforce.

ETHNIC–RACIAL SOCIALIZATION IN ASIAN CHILDREN OF IMMIGRANTS.

Asian Americans make up the second-largest ethnic group of immigrants in the United States. Asian immigrant parents see their status as members of a majority group disappear upon migrating to the United States (Kim et al. 2006). As new minorities, they may lack the experience necessary to teach their children about coping with discrimination. The ethnic–racial socialization scale (Juang et al. 2016) assesses how Asian American parents prepare their children to cope with the challenges of interpersonal and societal discrimination while also socializing their children to embrace diverse perspectives. They found that increasing diversity and cultural awareness related to stronger ethnic identity as well as to greater perceived discrimination, suggesting that ethnic–racial socialization can be both a risk and protective factor for adolescent development in Asian Americans. Wang & Benner (2016) extended this work to examine how socialization toward the mainstream society and socialization about one’s ethnicity are both practiced by multiple agents (not only by parents, but also by peers). Using a diverse sample of adolescents that included children of immigrants, they found that congruity in mainstream and ethnic socialization from parents and peers resulted in more positive adolescent mental health.

THE ROLE OF PHYSIOLOGY IN THE MENTAL HEALTH OF CHILDREN OF IMMIGRANTS.

The current research on the mental health of children of immigrants has relied mainly on reports of perceived stressors, especially discrimination. An emerging body of research is demonstrating the ways in which such stressors can get under the skin to influence physiological changes, such as changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning. Perceived discrimination related to greater overall cortisol output in a sample of Mexican American adolescents (Zeiders et al. 2012), and it also related to flatter diurnal slope in ethnic minority young adults, both of which indicate more dysfunctional cortisol rhythms (Zeiders et al. 2014). Psychological stressors experienced early in the life course (e.g., poverty, discrimination) can also result in inflammation, as evidenced by elevated levels of C-reactive protein, which is considered a precursor of depression and cardiovascular disease (Goosby et al. 2015, Miller et al. 2011). As dysregulated cortisol functioning and inflammation can relate to a range of health disparities, including in mental health functioning, an important avenue for future research would be understanding the physiological underpinnings of stressors commonly experienced by children of immigrants to deliver the most effective interventions (McEwen 2004, Miller et al. 2011).

SUMMARY POINTS.

Among both Asian Americans and Latinos, individuals who migrate before adolescence are at similar risk for psychiatric disorders as US-born individuals.

Asian children of immigrant backgrounds in the United States are particularly at risk for internalizing problems.

Relative to documented adolescents, undocumented adolescents and children in mixed-status families are at elevated risk for anxiety.

Parental experiences of discrimination relate to adolescent delinquency and depressive symptoms via increased paternal depressive symptoms and parental hostility toward adolescents.

Parent–child dyads with matching acculturation levels experience more supportive parenting and fewer adolescent depressive symptoms, whereas dyads with mismatched acculturation report less supportive parenting and more depressive symptoms.

Asian bilingual children of immigrants show slower growth in internalizing and externalizing problems over time relative to monolingual children.

Ethnic identity affirmation has a robust relationship with positive mental health and can mitigate the negative effects of discrimination.

Relative to DACA-ineligible individuals, those who were DACA eligible showed lower levels of psychological distress.

FUTURE ISSUES.

An up-to-date national study to ascertain the prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses in a US adolescent sample by nativity is needed.

Relative to studies of Latino children of immigrants, there are fewer studies of Asian children of immigrants in the United States. As the number of Asian Americans is expected to surpass the number of Latino immigrants in the future, more research attention to this population is needed.

Migration stressors related to the context of exit from the country of origin and entrance into the United States have been studied in reference to refugee children and unaccompanied minors, but we know less about the role of these experiences in the development of immigrant children more generally.

Children of immigrants are faced with both transcultural and culture-specific challenges, and real-time interventions targeting changes in these stress responses may be most fruitful in improving their mental health.

The exact mechanisms through which bilingual advantage, characterized by enhanced executive functioning, relates to better mental health need to be identified.

Longitudinal studies that follow immigrant children from their experiences in their countries of origin, to their experiences journeying to the United States, to their post-settlement experiences are needed to understand their mental health prospectively.

More long-term follow-up is needed for intervention studies that have targeted children of immigrants into adulthood to incorporate life-course perspectives on health and the potential cumulative impact of interventions over time on the mental health of children of immigrants.

An immigration policy allowing a path to citizenship in the United States for undocumented children and their parents will allow them to realize a more secure future, free from the fear of deportation, and will improve their long-term mental health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants to S.Y.K. from the National Science Foundation, Division of Behavioral and Cognitive Sciences (1651128 and 0956123), and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5R03HD060045-02 and 5R03HD051629-02), and by grants to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2P2CHD042849-16).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

K.M.P. is a board member of the Population Association of America and a coinvestigator of the Hispanic Community Health Study, supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (contract N01-HC65233).

Glossary

- First generation

individuals who are foreign born; also known as immigrants

- Second generation

individuals who are US born, with at least one foreign-born parent

- Third or later generation

individuals who are US born, with US-born parents

- Mixed-status families

families with some members who are undocumented and other members who have legal status

- Unaccompanied minors

children who migrate to the United States without their caregivers

- Transnational families

families whose members maintain relationships across one or more countries

- Transcultural

factors that can be applied generally to any ethnic, racial, or nativity group

- Culture specific

factors that are more relevant to ethnic/racial minorities and immigrant groups

- Immigrant paradox

refers to evidence indicating that immigrants have better health despite their lower socioeconomic status relative to those who are native born

- NLAAS

National Latino and Asian American Study

- Add Health

National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health

- Language brokers

children who act as intermediaries and translators for English-limited individuals

- DACA

Deferred Action for Child Arrivals

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Torres M, Polo A, Cao Z, Canino G. 2007. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across Latino subgroups in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 97:68–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Reports prevalence rates for psychiatric disorders in the Latino population from NLAAS.

- Am. Immigr. Counc. 2015. A Guide to Children Arriving at the Border: Laws, Policies, and Responses Washington, DC: Am. Immigr. Counc. [Google Scholar]

- Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Washington, DC: Am. Psychiatr. Assoc; 4th ed. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas E, Goldman N, Pebley AR, Teruel G. 2015. Return migration to Mexico: Does health matter? Demography 52:1853–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenta BE, Lee RM, Pituc ST, Jung K-R, Park IJK, et al. 2013. Where are you from? A validation of the Foreigner Objectification Scale and the psychological correlates of foreigner objectification among Asian Americans and Latinos. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 19:131–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Demonstrates the pernicious effect of foreigner stress on Asians and Latinos.

- Bacallao ML, Smokowski PR. 2005. “Entre Dos Mundos” (Between Two Worlds): bicultural skills training with Latino immigrant families. J. Prim. Prev. 26:485–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacio GA, Mays VM, Lau AS. 2013. Drinking initiation and problematic drinking among Latino adolescents: explanations of the immigrant paradox. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 27:14–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]