Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Maternal race may be an important risk factor for postpartum readmissions and associated adverse outcomes.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the association of race with serious complications during postpartum readmissions.

STUDY DESIGN:

This repeated cross sectional analysis utilized the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project from 2012 to 2014. Women ages 15 to 54 readmitted postpartum after a delivery hospitalization were identified by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria. Race and ethnicity were characterized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific islander, Native American, other, and unknown. Overall risk for readmission by race was determined. Risk for severe maternal morbidity during readmissions by race was analyzed. Individual outcomes including pulmonary edema/acute heart failure and stroke were also analyzed by race. Log-linear regression models including demographics, hospital factors, and comorbid risk were used to analyze risk for severe maternal morbidity during postpartum readmissions.

RESULTS:

Out of 11.3 million births, 207,730 (1.8%) women admitted postpartum from 2012 to 2014 were analyzed including 96,670 white, 47,015 black, and 33,410 Hispanic women. Compared to non-Hispanic white women, non-Hispanic black women were at 80% higher risk of postpartum readmission (95% confidence interval (CI) 79%-82%) while Hispanic women were at 11% lower risk of readmission (95% CI 10%-12%). In unadjusted analysis, compared to non-Hispanic white women, non-Hispanic black women admitted postpartum were at 27% higher risk of severe maternal morbidity (95% CI 24-30%) while Hispanic women were at 10% lower risk (95% CI 7-13%). In the adjusted model, non-Hispanic black women were at 16% higher risk for severe maternal morbidity during readmission than non-Hispanic white women (95% CI 10-22%) while Hispanic women were at 7% lower risk (95% CI 1-12%). Differences in severe maternal morbidity risk between other racial groups and non-Hispanic white women were not significant. In addition to overall morbidity, non-Hispanic black women were at significantly higher risk for eclampsia, ARDS, and renal failure than other racial groups (p<0.05 all). Black women were at 126% higher risk for pulmonary edema/acute heart failure than white women (95% CI 117-136%).

CONCLUSION:

Black women were more likely (i) to be readmitted postpartum, (ii) to suffer severe maternal morbidity during readmission, and (iii) to suffer life threatening complications such as pulmonary edema / acute heart failure. At-risk women including black women with cardiovascular risk factors may benefit from short-term postpartum follow up.

Keywords: postpartum readmissions, severe maternal morbidity, race, ethnicity, disparities

Condensation

Black women were more likely to be readmitted postpartum, to experience severe morbidity when readmission occurred, and to experience life-threatening complications such as pulmonary edema and heart failure.

INTRODUCTION

Obstetric readmissions may be of increasing clinical importance. Overall risk for postpartum readmission is increasing with a recent study finding an increase from 1.7% in 2004 to 2.2% in 2011.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has recently updated recommendations regarding postpartum care stating, “To optimize the health of women and infants, postpartum care should become an ongoing process, rather than a single encounter, with services and support tailored to each woman’s individual needs.”2 Traditional approaches to postpartum care are being reconsidered in hopes of reducing adverse postpartum maternal outcomes and risk for readmission.3

An important consideration in optimizing postpartum care is appropriately characterizing maternal risk. Prior studies have identified a range of risk factors for readmission including advanced age, socioeconomic status, chronic comorbidities, multiple gestation, cesarean delivery, and other high risk pregnancy conditions.1,4,5 Maternal race may represent a particularly important risk factor for postpartum readmissions and associated complications. Maternal race is a major risk factor adverse obstetric outcomes, and a number of prior analyses have addressed disparities in overall risk for severe morbidity and mortality.6-8 While race has been associated with increased risk for postpartum risk in smaller samples,4 national estimates of postpartum readmissions and associated complications have not been well characterized. A better understanding of how race is associated with postpartum risk may be useful in risk stratification and designing improvements in maternal care.

Given the knowledge gap regarding race and postpartum readmissions, the objectives of this study were to characterize (i) risk for postpartum readmissions by race, and (ii) describe risk for severe, life-threatening complications during these hospitalizations.

METHODS

The National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS) from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project for the years 2012-2014 was used for this repeated cross sectional analysis. The NIS is a large, publicly available, all-payer inpatient contains a sample of approximately 20% of all hospitalizations in the United States. These hospitalizations are selected via a stratified systemic random sample to generate a population representative of the entire US across medical specialties that includes academic, community, nonfederal, general, and specialty-specific centers. Weights can be applied to create national estimates. Approximately 8 million hospital stays from a total of 45 states were included in the NIS in 2010. 9

For this analysis postpartum readmissions after a delivery hospitalization were captured with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provided the algorithm used to identify postpartum hospitalizations .10,11 We included women aged 15 to 54. The primary exposure of interest was self-reported maternal race and ethnicity. Maternal race is categorized by the NIS as: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, other, or unknown. The years 2012 to 2014 were used for the analysis given that the proportion of missing data for race in the NIS for these years is small compared to preceding iterations. Women with a code for a delivery hospitalization (ICD-9-CM 650 or V27.x) were excluded. The Columbia University Institutional Review Board deemed this analysis exempt given that the data are deidentified,.

The primary outcome of this study was risk for severe maternal morbidity (SMM) as defined by the CDC during a postpartum readmission. The composite CDC definition of SMM includes 21 diagnoses including shock, stroke, heart failure, transfusion, and other conditions all identified using ICD-9-CM codes.11 A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding transfusion and retaining the remaining 20 diagnoses given that transfusion is the most common complication in the composite. In addition to the primary outcome of SMM, we evaluated two secondary outcomes. First, we evaluated overall risk for postpartum readmissions. Because the NIS is cross sectional and does not allow linkage of hospitalizations for individual patients, readmission risk was calculated with the number of deliveries each year as denominator for each racial category. Second, we evaluated risk for eleven individual severe morbidity outcomes within the CDC composite: (i) acute renal failure, (ii) acute respiratory distress syndrome, (iii) disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), (iv) eclampsia, (v) stroke, (vi) hysterectomy, (vii) shock, (viii) embolism, (ix) sepsis, (x) pulmonary edema and acute heart failure (PE/AHF), and (xi) transfusion. These conditions were chosen because they represent a broad range clinical pathology and were anticipated to be sufficiently prevalent to make meaningful comparisons.10

Demographic factors, hospital characteristics, and comorbidity were evaluated by NIS race categories and compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Hospital characteristics included bed size (small, medium, or large), location and teaching status (urban teaching, urban non-teaching, and rural), and region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West). Demographic categories included year of delivery, insurance status (Medicaid, private, Medicare, other, uninsured), and ZIP code income quartile. Comorbidity was evaluated using an obstetric comorbidity index which measures underlying patient risk.12 An important consideration in evaluating population-based outcomes is appropriate risk adjustment. For evaluating morbidity and death, there are comorbidity indices that have been developed in medical and surgical populations that account for underlying risk. This comorbidity index has been developed specifically for an obstetric population. In creating the obstetric comorbidity index, a list of maternal comorbidities possible associated with increased risk for maternal morbidity and mortality was developed. These risk factors were analyzed within an initial obstetric sample population and used to construct an adjusted model using a fully stepwise selection algorithm for both entry and retention in the model. The outcome was either severe maternal morbidity or mortality during the delivery hospitalization or postpartum. Potential risk factors included 24 maternal comorbidities and maternal age categorized as <19, 20–34, 35–39, 40–44, and >44 years of age. Risk factors found to be significant were retained in the model and then tested in a validation cohort of the same population. The final model includes 20 maternal conditions and maternal age. This comorbidity index provides weighted scores for comorbidity for obstetric patients based on specific diagnosis codes and demographic factors that can be ascertained in administrative data. Higher scores are associated with increased risk for severe morbidity. In the initial study validating the comorbidity index in a general obstetric population, patients with the lowest score of 0 had a 0.7% risk of severe morbidity while scores of >10 were associated with a risk of severe morbidity of 10.9%. This comorbidity index was subsequently validated in an external population.13 We categorized women based on comorbidity index scores: 0 (lowest risk), 1 or 2, and >2 (highest). Because maternal age is presented separately in our analysis to demonstrate the effect of this factor, this variable was omitted in calculating the comorbidity index score. A supplemental analysis includes the full comorbidity score and excludes maternal age as a separate variable. Adding the comorbidity index score to the adjusted analysis allows for the analysis to better characterize the effect of race accounting for other underlying risk factors. Adjusted risk ratios (aRR) for severe morbidity including transfusion with 95% confidence intervals (CI) as measures of effect accounting for comorbidity, demographic characteristics, and hospital factors were derived from fitting a log-linear regression model. Population weights can be applied to data in the NIS to create national estimates; these weights were applied in this study. All analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

From 2012 to 2014 an estimated 11.3 million births and 207,730 (1.8%) postpartum readmissions were ascertained from the NIS and included in the analysis. The proportion of non-Hispanic black women readmitted relative to delivery hospitalizations was significantly larger (3.09%, 95% CI 3.06%-3.12%, n=47,015/1,523,190) than other groups including non-Hispanic white women (1.71%, 95% 1.70%-1.72%, 96,670/5,650,075), Hispanic women (1.52%, 95% CI 1.50%-1.54%, 33,410/2,194,500), Asian or Pacific Islander women (1.17%, 95% CI 1.14%-1.20%, 6,930/592,025), Native American women (2.25%, 95% CI 2.15%-2.35%, 1,855/82,315), and women of other and unknown race (1.74%, 95% CI 1.70%-1.78%, 8,895/516,450; 1.83%, 95% CI 1.80%-1.86%, 12,865/702,315, respectively) (p<0.01). Overall, readmissions for non-Hispanic black women relative to delivery hospitalizations were 80.4% more likely than for non-Hispanic white women (95% CI 78.5%-82.4%, p<0.01).

Among readmissions Hispanic women were younger than non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white women, while Asian or Pacific Islander women were the oldest (Table 1). Non-Hispanic black and Hispanic women were more likely to receive Medicaid insurance than Asian or Pacific Islander or non-Hispanic white women (62.9% vs. 62.5% vs. 32.9% vs. 39.8%, respectively, p<0.01), and more likely to be from the lowest ZIP code income quartile (49.1% vs. 36.2% vs. 14.2% vs 25.1%, respectively, p<0.01). Compared to non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and Asian or Pacific Islander women, non-Hispanic black women had the highest rates of mild, severe, and superimposed preeclampsia (p<0.01). Finally, excluding age and preeclampsia, non-Hispanic black women had higher comorbidity scores; 3.6% of non-Hispanic black women had a score >2 and 21.8% a score of 1 or 2 compared with 1.2% and 16.7% of non-Hispanic white women, 0.9% and 12.7% of Hispanic women, and 2.5% and 9.3% of Asian or Pacific Islander women (p<0.01).

Table 1.

Demographics of patients readmitted postpartum

| White non- Hispanic |

Black non- Hispanic |

Hispanic | Asian/Pacific Islander |

Native American |

Other | Unknown | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients(n) | 96,670 | 47,015 | 33,410 | 6,930 | 1,855 | 8,985 | 12,865 |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Maternal age | |||||||

| 15-17 | 1.8% | 2.4% | 4.0% | 0.6% | 2.2% | 1.9% | 2.5% |

| 18-24 | 26.9% | 31.5% | 33.1% | 12.3% | 36.1% | 27.7% | 26.7% |

| 25-29 | 26.9% | 25.6% | 25.6% | 23.4% | 27.5% | 26.7% | 27.8% |

| 30-34 | 26.3% | 22.5% | 21.4% | 35.0% | 19.1% | 25.4% | 26.7% |

| 35-39 | 13.7% | 13.1% | 12.3% | 21.6% | 11.6% | 13.8% | 12.5% |

| ≥40 | 4.5% | 4.9% | 3.6% | 7.1% | 3.5% | 4.6% | 3.8% |

| Year | |||||||

| 2012 | 33.7% | 32.7% | 34.5% | 33.6% | 37.7% | 36.0% | 31.8% |

| 2013 | 32.6% | 33.4% | 32.1% | 31.0% | 32.3% | 30.6% | 35.5% |

| 2014 | 33.7% | 33.9% | 33.4% | 35.4% | 29.9% | 33.4% | 32.7% |

| Hospital bed size | |||||||

| Small | 12.8% | 9.9% | 11.9% | 10.5% | 13.5% | 11.9% | 13.4% |

| Medium | 26.6% | 29.2% | 28.6% | 29.4% | 26.1% | 28.2% | 27.1% |

| Large | 60.6% | 60.9% | 59.5% | 60.1% | 60.4% | 60.0% | 59.5% |

| Insurance status* | |||||||

| Medicare | 1.8% | 4.1% | 0.9% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.2% | 3.7% |

| Medicaid | 39.8% | 62.9% | 62.5% | 32.9% | 59.3% | 54.1% | 38.8% |

| Private | 51.3% | 27.1% | 25.4% | 60.4% | 23.7% | 35.1% | 49.9% |

| Self-pay | 3.0% | 3.2% | 7.4% | 3.2% | 5.9% | 6.0% | 3.1% |

| Other | 3.9% | 2.5% | 3.5% | 2.6% | 10.0% | 3.4% | 4.2% |

| Hospital Location | |||||||

| Rural | 11.4% | 3.9% | 3.9% | 3.2% | 25.6% | 4.6% | 12.6% |

| Urban non teaching | 31.8% | 24.3% | 33.6% | 28.4% | 26.7% | 29.2% | 20.2% |

| Urban teaching | 56.7% | 71.8% | 62.5% | 68.4% | 47.7% | 66.2% | 67.2% |

| ZIP Income Quartile | |||||||

| 1st (lowest) | 25.1% | 49.1% | 36.2% | 14.2% | 45.3% | 30.3% | 23.7% |

| 2nd | 27.0% | 22.3% | 25.8% | 18.0% | 24.5% | 23.2% | 29.8% |

| 3rd | 24.9% | 16.1% | 22.9% | 26.8% | 15.9% | 23.9% | 25.8% |

| 4th (highest) | 21.8% | 10.2% | 12.2% | 39.4% | 7.8% | 19.8% | 18.9% |

| Unknown | 1.2% | 2.2% | 2.9% | 1.7% | 6.5% | 2.8% | 1.7% |

| Hospital Region | |||||||

| Northeast | 18.5% | 19.1% | 15.9% | 19.8% | 4.6% | 30.8% | 4.4% |

| Midwest | 22.4% | 19.4% | 7.4% | 11.5% | 14.6% | 17.0% | 60.3% |

| South | 41.6% | 53.3% | 37.0% | 20.6% | 31.8% | 36.0% | 16.7% |

| West | 17.6% | 8.1% | 39.7% | 48.0% | 49.1% | 16.2% | 18.7% |

| Comorbidity index | |||||||

| 0 | 82.2% | 74.5% | 86.4% | 88.2% | 76.3% | 85.7% | 81.5% |

| 1 or 2 | 16.7% | 21.8% | 12.7% | 9.3% | 23.2% | 13.0% | 16.9% |

| >2 | 1.2% | 3.6% | 0.9% | 2.5% | 0.6% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| Preeclampsia | |||||||

| Mild | 6.1% | 9.2% | 4.1% | 5.9% | 2.7% | 6.1% | 4.6% |

| Severe | 4.9% | 8.0% | 4.1% | 5.9% | 5.4% | 6.5% | 6.0% |

| Superimposed | 1.8% | 4.2% | 1.5% | 1.9% | 1.6% | 2.3% | 1.6% |

Comorbidity index excludes maternal age and hypertensive diagnoses.

Unknown insurance status not demonstrated given cell size <10.

During readmissions, non-Hispanic black women were at higher risk for severe maternal morbidity including transfusion (24.3%) than all other groups including non-Hispanic white (19.1%), Asian or Pacific Islander (20.5%), Native American women (21.0%), and Hispanic women (17.2%) as well as women of unknown (20.2%) or other (19.1%) race (p<0.01). In the unadjusted model with non-Hispanic white women as the reference, this difference translated into a 27% increased risk (RR 1.27, 95% 1.24-1.30) for non-Hispanic black women while Hispanic women were at 10% lower risk (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.87-0.93). Women with Medicare compared to private insurance were at increased risk (RR 1.37, 95% 1.30, 1.45). Women age 40 or older and women age 35 to 39 were at increased risk for severe morbidity compared to women 18-24 years of age (RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.46-1.59; RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.20-1.28). Higher obstetric comorbidity index scores of 1-2 or >2 were also associated with increased risk for severe morbidity (RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.32, 1.38; RR 2.61, 95% CI 2.54, 2.69, respectively). In the adjusted analysis, many of these risk factors retained significance. Non-Hispanic black women were at increased risk for severe morbidity compared to non-Hispanic white women (aRR 1.16, 95% CI 1.10-1.22) while Hispanic women were at slightly lower risk (aRR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88-0.99). Medicare insurance was retained as a risk factor (aRR 1.18, 95% CI 1.06-1.30) (Table 2). Women age 40 or older and women age 35 to 39 were similarly at increased risk for severe morbidity compared to women 18-24 years of age (aRR 1.40, 95% CI 1.29-1.52; aRR 1.18, 95% CI 1.11-1.26). Finally, comorbidity index score of 1 or 2 and >2 were associated with increased risk compared to scores of 0 (aRR 1.28, 95% CI 1.23, 1.34; aRR 2.47, 95% CI 2.34, 2.60, respectively). When the analysis was repeated excluding maternal age as a separate variable and incorporating it into the obstetric comorbidity index, the estimate for comorbidity index score >2 compared to 0 was higher (aRR 3.14, 95% CI 2.98, 3.31) while estimates for other factors in the analysis was similar (Supplemental Table 1). When the sensitivity analysis was performed restricted to severe morbidity without transfusion, the risk differential was larger. Non-Hispanic black women were at 41.8% increased risk for severe morbidity excluding transfusion compared to non-Hispanic white women (21.0% vs. 14.8%) with risk also lower for Hispanic (13.3%), Asian or Pacific Islander (16.3%), and Native American women (16.7%) (p<0.01).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted models for severe morbidity during postpartum readmissions

| RR | 95% CI | aRR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.27 | 1.24, 1.30 | 1.16 | 1.10, 1.22 |

| Hispanic | 0.90 | 0.87, 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.88, 0.99 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.09 | 1.03, 1.15 | 1.05 | 0.95, 1.17 |

| Native American | 1.10 | 0.99, 1.21 | 1.08 | 0.89, 1.32 |

| Other | 1.00 | 0.95, 1.05 | 1.03 | 0.93, 1.13 |

| Unknown | 1.05 | 1.01, 1.10 | 1.02 | 0.94, 1.11 |

| Year | ||||

| 2012 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| 2013 | 1.05 | 1.03, 1.08 | 1.04 | 0.99, 1.09 |

| 2014 | 1.06 | 1.03, 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.08 |

| Hospital bed size | ||||

| Small | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Medium | 1.05 | 1.01, 1.08 | 1.02 | 0.95, 1.09 |

| Large | 1.11 | 1.07, 1.14 | 1.06 | 0.99, 1.12 |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Private | 1.00 | Refer ence | 1.00 | Reference |

| Medicare | 1.37 | 1.30, 1.45 | 1.18 | 1.06, 1.30 |

| Medicaid | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.94, 1.02 |

| Other | 0.85 | 0.81, 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.78, 0.97 |

| Uninsured | 1.00 | 0.95, 1.06 | 1.03 | 0.93, 1.14 |

| Hospital Location | ||||

| Urban non-teaching | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Rural | 0.96 | 0.93, 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.91, 1.07 |

| Urban teaching | 1.02 | 1.00, 1.04 | 0.97 | 0.93, 1.02 |

| Income Quartile | ||||

| 1st (lowest) | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| 2nd | 0.97 | 0.94, 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.95, 1.05 |

| 3rd | 0.94 | 0.92, 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.92, 1.02 |

| 4th (highest) | 0.92 | 0.90, 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.88, 1.00 |

| Hospital Region | ||||

| Northeast | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Midwest | 1.19 | 1.16, 1.24 | 1.20 | 1.12, 1.29 |

| South | 1.25 | 1.22, 1.29 | 1.25 | 1.18, 1.33 |

| West | 1.18 | 1.15, 1.22 | 1.27 | 1.18, 1.36 |

| Maternal age | ||||

| 15-17 | 0.96 | 0.90, 1.03 | 0.97 | 0.84, 1.11 |

| 18-24 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| 25-29 | 1.05 | 1.02, 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.09 |

| 30-34 | 1.14 | 1.11, 1.17 | 1.11 | 1.05, 1.17 |

| 35-39 | 1.24 | 1.20, 1.28 | 1.18 | 1.11, 1.26 |

| >39 | 1.53 | 1.46, 1.59 | 1.40 | 1.29, 1.52 |

| Comorbidity index | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| 1-2 | 1.35 | 1.32, 1.38 | 1.28 | 1.23, 1.34 |

| >2 | 2.61 | 2.54, 2.69 | 2.47 | 2.34, 2.60 |

Adjusted model included all factors in this table (year, bed size, insurance status, hospital location, income quartile, hospital region, hospital teaching status, maternal age, and race). RR, risk ratio. aRR, adjusted risk ratio. Comorbidity index excludes maternal age.

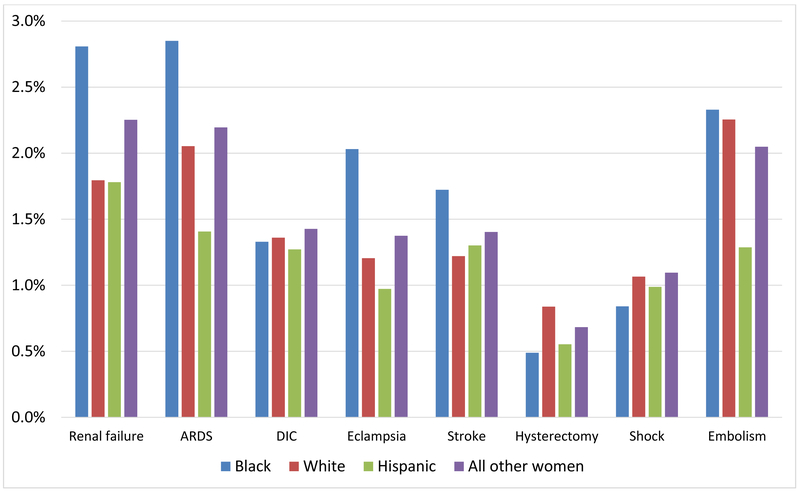

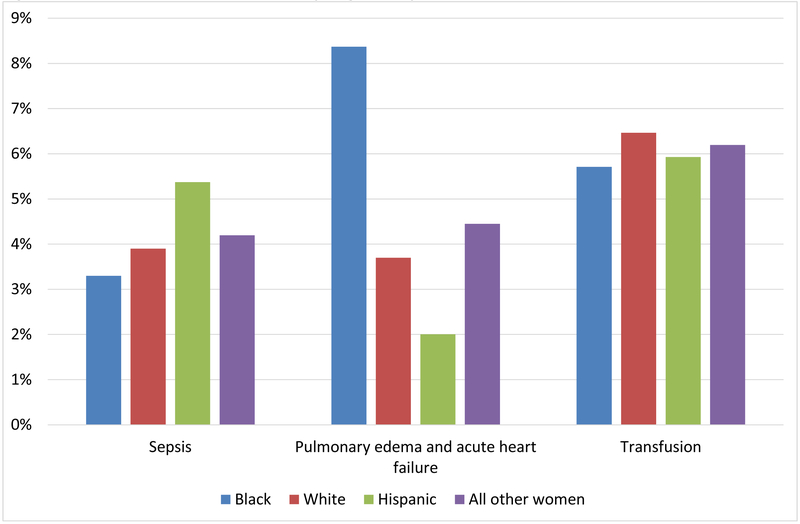

Evaluating individual severe morbidity outcomes, non-Hispanic black women were at significantly increased risk compared to non-Hispanic white women for several outcomes. Non-Hispanic black women were at increased risk for acute renal failure (RR 1.56, 95% CI 1.46-1.68), acute respiratory distress syndrome (RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.30-1.49), eclampsia (RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.55-1.83), and stroke (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.29-1.54) (Figure 1) with non-Hispanic white women as the reference. Non-Hispanic Black women were at particularly high risk for pulmonary edema and acute heart failure with 8.4% readmissions receiving diagnosis compared to 3.7% of non-Hispanic white women (RR 2.26, 95% CI 2.17-2.36) (Figure 2). Comparing these groups, non-Hispanic black women were at significantly lower risk for shock (RR 0.79, 95%CI 0.70-0.89), transfusion (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.85-0.93), sepsis (RR 0.85, 95% 0.80-0.90), and hysterectomy (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.50-0.68). Differences for risk between non-Hispanic black and white women were not significant for DIC and embolism.

Figure 1. Risk for individual severe morbidity diagnoses by maternal race.

Legend. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome. DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation. Compared to non-Hispanic white women, non-Hispanic black women were at significantly increased risk for acute renal failure, ARDS, eclampsia, and stroke (p<0.01 for all). Black women were at significantly decreased risk for hysterectomy and shock (p<0.01) while differences in DIC and embolism were not significantly different.

Figure 2. Risk for individual severe morbidity diagnoses by maternal race.

Legend. Compared to non-Hispanic white women, non-Hispanic black women were at significantly increased risk pulmonary edema and acute heart failure but decreased risk for transfusion or sepsis.

DISCUSSION

Main Findings

In this analysis of postpartum readmissions, non-Hispanic black women were at significantly higher risk (i) to be readmitted postpartum, (ii) to suffer severe maternal morbidity during readmission, and (iii) to suffer a range of life threatening complications. While non-Hispanic black women were at lower risk for complications such as sepsis, shock, hysterectomy, and transfusion, they were particularly likely to receive a diagnosis of pulmonary edema / acute heart failure, with risk more than twice as high as that of non-Hispanic white women.

Implications of the findings and future research directions

The differential risk found in this analysis may have a number of implications for optimizing postpartum care. First, because non-Hispanic black women were at much higher risk for readmissions relative to the number of births in the population, efforts to reduce maternal risk in this demographic may represent an important component of overall strategies to reduce postpartum risk and racial disparities. While this dataset is not able to link readmissions across hospitalizations, identifying preceding obstetric, medical, and social risk factors among non-Hispanic black women that contribute to differentials will be necessary to identify who may most benefit from more intensive postpartum care and surveillance. Second, non-Hispanic black women were at particularly high risk for cardiopulmonary complications. Because this dataset does not include outpatient data and chart reviews are not possible, we are not able to determine to what degree these conditions were preceded by outpatient symptoms or whether changes in management could have prevented readmissions. However, it is reasonable to assume that for at-risk women who develop cardio-pulmonary complications optimal postpartum care may facilitate timely diagnosis, multi-disciplinary care, and transfer to an appropriate level of inpatient care. Third, the relatively large differentials in risk for adverse outcomes supports ACOG’s recommendation that postpartum care be tailored. In comparison to intrapartum management, where a small number of conditions such as hemorrhage, hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, and thromboembolism account for the majority of risk among most women, postpartum risk may be more differentially distributed and comparative effectiveness research is needed to determine which interventions may most benefit individual populations. Specifically, further data is needed to determine potential benefits of longer inpatient stays for particularly high risk women, shorter office follow-up, mobile health interventions, increased coordination with medical specialists, and other approaches to reducing maternal risk. Fourth, while non-Hispanic black women were at lower risk than non-Hispanic white women for hysterectomy, sepsis, shock, and transfusion during readmissions, on a population basis relative to delivery hospitalizations non-Hispanic black women were at similar risk for hysterectomy and increased risk for the latter three conditions given overall likelihood of readmission.

Strengths and limitations

There are several limitations that are important to consider in interpreting this study’s findings. First, as noted, this data is cross sectional and we are not able to account for factors that occurred during the delivery or after hospital discharge prior to the readmission. We are not able to determine if a complication occurred on an outpatient basis or during the readmission. As a result, while there were clear differentials in outcomes noted between racial groups, we are not able to make inferences related to preventability or when a complication occurred. Second, this administrative data set does not provide information on hospital resources, infrastructure, protocols and staffing, all of which contribute to maternal outcomes and risk. Third, because administrative data is used primarily for billing data both under-ascertainment and misclassification of secondary diagnoses are concerns. While administrative data is appropriate is assessing population-level resource utilization and disease burden, granularity of many important clinical factors is often limited. Fourth, data on race was missing for 6% of patients of this study. If outcomes based on race differed significantly for patients with unknown compared with known race, the disparities reported may be biased. The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project provides a number of recommendations for addressing missing data including imputation.14 We decided not to perform imputation because it was unlikely that missing data on race were (i) randomly related to other measurable factors and (ii) nondifferential across the years of NIS included in this analysis. In determining whether to perform imputation important considerations are (i) whether specific outcomes in the actual population are related to higher likelihood that data is missing, and (ii) whether factors associated with the outcome of interest are related differentially to missing and non-missing data. HCUP documents support that specific outcomes may in fact have been related to missingness; for this missing data differential associations may be present between other measured factors..14 To address these concerns, HCUP in part suggests incorporating data outside the NIS, an approach beyond the scope of this analysis. Fifth, because hospitalizations are not linked we are not able to determine the time interval between delivery hospitalization discharge and readmission; subsequent analyses with data sources that allow evaluation of duration between discharge and readmissions may be important in optimizing care. Sixth, many complications that are primarily managed on an outpatient basis, such as wound complications, cannot be captured using this data. Seventh, we cannot control for the effect of multiple pregnancies occurring to individual women. We elected to use the NIS because it is a large, nationally representative sample, and for the 3 years of the study there were low rates of missing data compared with prior iterations in which data on race were missing for >20% of all hospitalizations. Other strengths of this study include measurement of readmissions, which are an adverse event in and of themselves, and assessment of a broad range of outcomes demonstrating major differentials in risk.

In conclusion, this analysis demonstrated increased risk among non-Hispanic black women for postpartum readmission and associated complications. Addressing this risk aligns with urgent priorities of optimizing postpartum care for at-risk women and reducing racial disparities in adverse obstetric outcomes. At-risk women including black women with cardiovascular risk factors may in particular benefit from closer surveillance including short-term postpartum follow up.

Supplementary Material

AJOG at a Glance.

A. Why was the study conducted?

To evaluate whether there are racial disparities in postpartum readmissions.

B. What are the key findings?

Black women were more likely to be readmitted, more likely to experience severe morbidity, and at higher risk for life-threatening complications such as pulmonary edema and heart failure.

C. What does this study add to what is already known?

Black women are at particularly high risk for specific postpartum readmission complications.

Acknowledgments

Funding Dr. Friedman is supported by a career development award (K08HD082287) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presentation This study is being presented at the 2019 Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Annual Meeting in Las Vegas Nevada

Conflict of interest Dr. Wright has served as a consultant for Tesaro and Clovis Oncology. The other authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clapp MA, Little SE, Zheng J, Robinson JN. A multi-state analysis of postpartum readmissions in the United States. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;215(1):113.e111–113.e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: Optimizing Postpartum Care. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018;131(5):e140–e150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray Horwitz ME, Molina RL, Snowden JM. Postpartum Care in the United States - New Policies for a New Paradigm. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(18):1691–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aseltine RH Jr., Yan J, Fleischman S, Katz M, DeFrancesco M. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Hospital Readmissions After Delivery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2015;126(5):1040–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharvit M, Rubinstein T, Ravid D, Shechter-Maor G, Fishman A, Biron-Shental T. Patients with high-risk pregnancies and complicated deliveries have an increased risk of maternal postpartum readmissions. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2014;290(4):629–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2011-2013. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2017;130(2):366–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Kuklina EV, Callaghan WM. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: a multistate analysis, 2008-2010. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;210(5):435 e431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;214(1):122 e121–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Introduction to the HCIP Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) 2010-2015. November 2017. Accessed at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nrd/Introduction_NRD_2010-2015.pdf.

- 10.Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;120(5):1029–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States. Accessed January 20, 2018 Available at: https://http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/severematernalmorbidity.html .

- 12.Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Development of a comorbidity index for use in obstetric patients. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;122(5):957–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metcalfe A, Lix LM, Johnson JA, et al. Validation of an obstetric comorbidity index in an external population. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2015;122(13):1748–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houchens R Missing Data Methods for the NIS and the SID 2015. HCUP Methods Series Report # 2015-01 ONLINE. January 22, 2015. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Accessed January 2018 Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/methods.jsp. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.