Abstract

Objective:

Recently, our laboratory identified sensory innervation within head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) and subsequently defined a mechanism whereby HNSCCs promote their own innervation via the release of exosomes that stimulate neurite outgrowth. Interestingly, we noted that exosomes from human papillomavirus (HPV)- positive cell lines were more effective at promoting neurite outgrowth than those from HPV-negative cell lines. As nearly all cervical tumors are HPV-positive, we hypothesized that these findings would extend to cervical cancer.

Methods:

We use an in vitro assay with PC12 cells to quantify the axonogenic potential of cervical cancer exosomes. PC12 cells are treated with cancer-derived exosomes, stained with the pan-neuronal marker (β-III tubulin) and the number of neurites quantified. To assess innervation in cervical cancer, we immunohistochemically stained cervical cancer patient samples for β-III tubulin and TRPV1 (sensory marker) and compared the staining to normal cervix.

Results:

Here, we show the presence of sensory nerves within human cervical tumors. Additionally, we show that exosomes derived from HPV-positive cervical cancer cell lines effectively stimulate neurite outgrowth.

Conclusions:

These data identify sensory nerves as components of the cervical cancer microenvironment and suggest that tumor- derived exosomes promote their recruitment.

Introduction

Cervical cancer, the second most common cancer in women worldwide, accounts for an estimated 260,000 deaths annually (1). Nearly all cases of cervical cancer are associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection (1). While HPV remains the most common newly diagnosed sexually transmitted infection (1), improved screening and vaccination have decreased the cervical cancer incidence in the United States over the past decade (2). In developing nations, however, where vaccination rates are poor and screening is inconsistent, the incidence of cervical cancer remains high (3). Indeed, approximately 85% of cervical cancer-associated deaths occur in developing nations (3). Thus, significant advancements in prevention and screening notwithstanding, cervical cancer remains a major global cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality, requiring novel insights into factors promoting disease progression and identification of new targets to better treat established disease.

The organ-like nature of solid tumors is increasingly appreciated. Complex webs of interactions between tumor cells, non-tumor cells, and non-cellular components that comprise the tumor microenvironment cumulatively define the physiologic behavior of the cancer as a whole. A thorough mapping of the cell types present and, critically, an understanding of their unique roles in tumor biology will provide new opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Interestingly, tumor innervation is associated with worse clinical outcomes in several solid cancers (4–6), emphasizing nerves as microenvironmental factors that may contribute to tumor progression. It is important to note the distinction between innervation and the more commonly recognized perineural invasion. While the latter refers to the phenomenon of tumor cell invasion into and along the perineural sheath of nerve bundles, the former refers to the infiltration of nerves into the tumor parenchyma. Evidence suggests that tumor innervation is an active process driven, at least in part, by tumor cell-mediated recruitment of nearby nerves (7,8). Recently, our laboratory identified sensory innervation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and showed that HNSCC-released exosomes, small extracellular vesicles that carry diverse cargo, promote neurite outgrowth and tumor innervation (9). Interestingly, this effect appeared to be associated with exosomes derived from HPV-positive HNSCC cells (9). These findings suggest that HPV-mediated cellular changes may confer exosomes with an enhanced ability to stimulate neurite outgrowth.

In light of these findings, we hypothesized that, given the near universal association with HPV, cervical cancer would exhibit a similar phenomenon. Here, as with HNSCC, we characterized cervical cancer innervation as sensory in nature by immunohistochemistry. Additionally, we identified neuritogenic activity in exosomes derived from cervical cancer cell lines. These data suggest that cervical cancers are innervated and that tumor released exosomes mediate this innervation.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Caski, SiHa, and HeLa cells were a generous gift from Dr. Aloysius Klingelhutz (University of Iowa) and maintained in DMEM (Corning, #10–017-CV) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, #SH3039.03) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution (Corning, #30–002-CI). The isogenic pair of cell lines, C66–7 and C66–3, were a generous gift from Dr. John H. Lee (NantKwest). Both cell lines were generated from primary, HPV negative cervical keratinocytes from the same patient which were transduced with Ad/Cre and Ad/HPV16/eGFP; the generation of these cell lines and their characterization was published by Lee et al (10). Both of these cell lines were maintained in E-medium: 3:1 ratio of DMEM:Ham’s F12 nutrient mixture (Corning, #10–080-CV), supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone, 5 μg/mL transferrin, 5 μg/mL insulin, 1.36 ng/mL tri-iodo-thyronine, and 5 μg/mL epidermal growth factor. PC12 cells were purchased from ATCC and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% horse serum (Gibco, #26050–088), 5% FBS, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All cells were maintained with humidified 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator.

Human Samples

Normal cervix (n=10) and cervical cancer (n=30) cases were obtained from the Penn Ovarian Cancer Research Center Tumor BioTrust Collection and the Department of Pathology at the University of Pennsylvania (https://www.med.upenn.edu/OCRCBioTrust/). All cancer cases were verified by a pathologist (LES) and were treatment naïve. Unstained sections were cut at 5 um and shipped to Sanford Research for immunohistochemical staining.

Immunohistochemistry

None of the tissues in this study associated with protected human information (PHI) and were originally collected for other purposes. Thus, our experiments were exempt from Institutional Review Board approval. Tissues were stained using a BenchMark XT slide staining system (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.). The Ventana iView DAB detection kit was used as the chromogen and slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. Antibodies used for staining were: anti-β-III tubulin (Abcam, ab78078; 1:250); anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (Abcam, ab112; 1:750); anti-VIP (Abcam, ab22736; 1:100); anti-TRPV1 (Alomone, ACC-030; 1:100). H&E staining followed standard procedures.

Scoring of IHC stained samples

An unbiased scoring system was established as follows. β-III tubulin and TRPV1 IHC stained human samples were analyzed on an Olympus BX51 bright field microscope. We did not score TH or VIP staining as these were largely negative in normal cervix and cervical cancer specimens. Sections were viewed under 20X magnification. Five random fields/sample were analyzed and scored. Three independent evaluators (MM, CTL, PDV) scored all samples. Scores were averaged. A score of 0 indicates no staining in the evaluated field; +1 indicates 0–10% staining; +2 indicates 30–50% staining; +3 indicates greater than 50% staining.

Immunofluorescence

Formalin fixed paraffin-embedded sections were de-paraffinized and rehydrated as follows: 100% Histo-Clear (National Diagnostics) for 5min, 100% ethanol for 1 min, 90% ethanol for 1 min, 70 % ethanol for 1 min and finally in PBS for 1 min. Before immunofluorescent staining, an antigen retrieval step was performed by incubating sections in 10 mM Sodium Citrate Buffer (10 mM Sodium Citrate Buffer, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0) at 95° C for 1 hour. After cooling to room temperature for 30 min, slides were washed with PBS and blocked in blocking buffer (1X PBS, 10% goat serum, 0.5% TX- 100, 1% BSA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at +4°C. β-III tubulin antibody (Abcam, cat# 78078) was used at a dilution of 1:250, while anti-TRPV1 antibody (Alomone labs, cat# ACC-030) was used at 1:100 dilution. Slides were washed three times in PBS for 5 min each and incubated in secondary antibodies and Hoescht (1:10000, Invitrogen) at room temperature. Slides were washed three times in PBS for 5 min each and coverslips were mounted by using Faramount Mounting media (Dako). Immunostained sections were analyzed on an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope equipped with a laser scanning fluorescence and a 12 bit camera. Images were taken using a 60x oil PlanApo objective (with and without zoom feature).

Exosome Isolation, Quantification, and Validation

Exosome isolation followed our previously described protocol (9). Briefly, cells were seeded on two 150mm plates per cell line with 8 mL of DMEM with 10% exosome- depleted FBS (Gibco, #A27208–01) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. 48-hours later, conditioned medium was collected, pooled, and exosomes were purified by differential ultracentrifugation as follows. Conditioned medium was centrifuged at 300 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C to pellet cells. The resulting supernatant was transferred to new tubes and centrifuged at 2,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant was again transferred to new tubes and centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant from this spin was transferred to sterile PBS-rinsed ultracentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 100,000 x g for 120 minutes at 4°C in a SureSpin 630/17 rotor (Sorvall). The resulting exosome pellet was washed in sterile PBS, and re-centrifuged at 100,00xg for 120 min. The final pellet was re-suspended in 400 μL sterile PBS. Exosomes were stored at −20°C in 50μL aliquots.

Exosome protein concentration was quantified using a modified BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as previously described (9). 50 μL of purified exosomes was mixed with 5 μL of 10% TX-100 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. BCA assay proceeded with a sample-to-working reagent ratio of 1:11. Samples were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C and absorbance was measured at 562 nm using a SpectraMax Plus 384. Protein concentration was estimated using a quartic model fit to the standard curve.

The presence of exosomes was validated via western blot analyses of the exosomal markers CD9 and CD81. Equal total protein (~1.5 μg) was separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P, Millipore), and blocked with 5% bovine albumin (Affymetrix/USB, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #AAJ10857A1). Membranes were washed in TTBS (0.05% Tween-20, 1.37 M NaCl, 27 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris Base). Primary antibodies used for western blot were: anti-CD81 (Santa Cruz, sc166029; 1:100 in TTBS, overnight at 4°C) and anti-CD9 (Abcam, ab92726; 1:350 in TTBS, overnight at 4°C). After washing, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000 in TTBS) for one hour. Following another wash in TTBS, membranes were incubated with chemiluminescent substrate (SuperSignal West Pico, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged using a UVP GelDocIt 310 imaging system equipped with a high resolution 2.0 GelCam 310 CCD camera.

PC12 Neurite Outgrowth Assay

PC12 cells were seeded on collagen-coated (collagen type VI, Sigma-Aldrich, C5533) 96- well black, optical-bottom, flat-bottom plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and grown in DMEM containing 1% horse serum, 0.5% FBS, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. PC12 cells were seeded at a density of 15,000 cells per well. After seeding, PC12 cells were incubated at room temperature for 20 min to allow for an even distribution and adherence of cells. PC12 cells were then stimulated with 3 ug of exosomes and returned to the incubator. Cells used as positive controls were stimulated with recombinant NGF (Abcam, ab179616, final concentration of 50ng/uL) while unstimulated cells (PBS alone) served as the negative controls. All cells were maintained under these treatments for 72 hours in a humidified incubator set at 37°C with 5% CO2. For all conditions, serum concentrations were adjusted to achieve final concentrations of 1% horse serum and 0.5% FBS. After 72 hours of treatment, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, then blocked and permeabilized by incubating in a solution containing 3% donkey serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.5% TX-100 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed with PBS prior to incubation with an anti-β-III tubulin antibody (Millipore, AB9354; 1:1,500 in the blocking solution above) for 48 hours at 4°C. Cells were washed again with PBS, prior to incubation with an anti-chicken 488 antibody (Invitrogen, A11039; 1:2000 in blocking solution above) and Hoechst 33342 (1:2000) for one hour at room temperature. Cells were washed with PBS and 100 μL fresh PBS was added to prevent drying. Neurite quantification was performed on the Cell-In-sight CX7 HCS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the Cellomics Scan Software’s (Version 6.6.0, Thermo Fisher Scientific) Neuronal Profiling Bioapplication (Version 4.2). 25 fields were imaged in each well with a 10x objective with 2×2 binning. Nuclei were identified by Hoechst-positive staining, while cell bodies and neurites were identified by β-III tubulin-positive staining. Neurons were identified as those cells with a Hoechst-positive nucleus and β-III tubulin-positive cell body. Neurites longer than 20 μm were included in the analysis. Data are represented as fold induction of neurite outgrowth over negative control (PBS alone).

Results

Neuronal Markers in Cervical Cancer

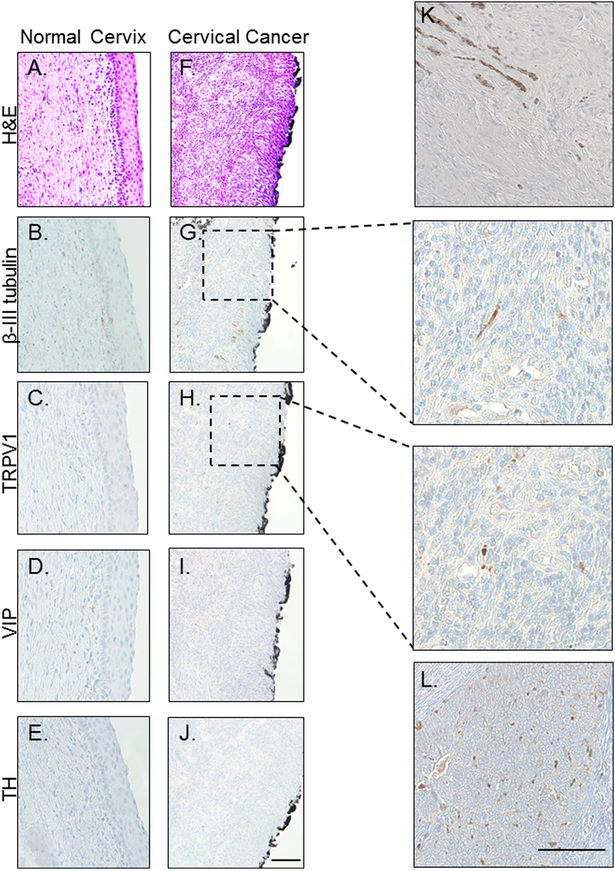

Recently, our laboratory investigated the presence of nerves within HNSCC patient samples via immunohistochemistry (9). Consistently, we observed the intra-tumoral presence of the pan-neuronal marker, β-III tubulin, suggesting that HNSCCs are innervated (9). For further characterization, we stained samples for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a marker of sympathetic nerves; vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), a marker of parasympathetic nerves; and transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 channel (TRPV1), a marker of nociceptive sensory nerves. Notably, HNSCC tumors were consistently negative for TH and VIP, but positive for TRPV1, suggesting the presence of sensory innervation, as opposed to autonomic (9). As the majority of cervical cancers are also squamous cell carcinomas (11) and share a common causal agent, HPV, with a growing subset of HNSCC (12), we hypothesized that our findings would extend to this tumor type. We first investigated the innervation of normal cervical tissue (n=10 samples). Consistent with the published literature, we found single, β-III tubulin positive nerves scattered throughout the stroma but not crossing into the squamous epithelium proper (Figure 1A, B)(13). While sparse VIP positive fibers were present in a few specimens, the majority were largely negative for VIP as well as TH. (Figure 1C, D). A few sparse fibers were positive for TRPV1 (Figure 1C).

Figure 1: Cervical cancer is innervated.

Representative bright field images of normal cervix (A-E) and cervical cancer (F-L) stained with H&E (A,F) and immunohistochemically stained for β-III tubulin (B,G), TRPV1 (C,H), VIP (D,I) and TH (E,J.). Panels K and L are examples of robust β-III tubulin and TRPV1 staining, respectively. Scale bars, 50 μm. Black boarding the cervical cancer is ink from the surgical procedure.

Squamous carcinoma of the cervix emerges via a step-wise progression from HPV infection to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN, stages 1–3) and finally to invasive carcinoma (14). While the distinction between the stroma and the overlying squamous epithelium is clear in the normal cervix (Figure 1A–E) and retained in CIN 1, 2 and 3, it becomes blurred in invasive carcinoma where increased expression/function of proteases degrade the basement membrane, allowing for tumor invasion into the underlying stroma and beyond (15). As such, immunohistochemical staining of cervical cancer cases for neuronal markers predominantly represents a mixture of cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts. All cervical cancer samples analyzed (N=30) demonstrated variable β-III tubulin expression and (Figure 1G, inset at higher magnification) were also TRPV1 positive (Figure 1H, inset at higher magnification) but negative for TH and VIP (Figure 1I,J). These data indicate that cervical cancers contain sensory nerves. Figures 1K and 1L show cervical cancer cases with more robust β-III tubulin and TRPV1 immunostaining, respectively.

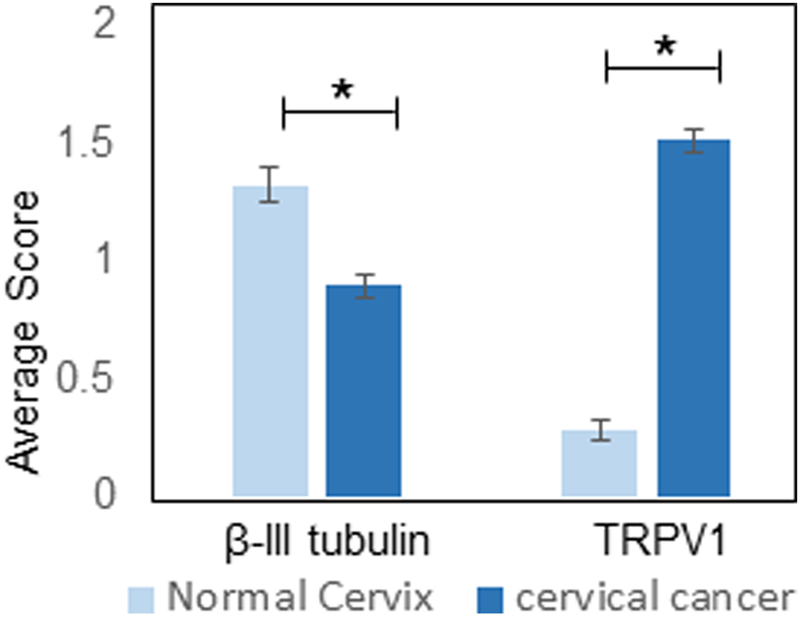

To determine if the extent of innervation changes with carcinogenesis, sensory innervation (β-III tubulin and TRPV1) in normal cervix and cervical carcinoma cases was scored as described in the Methods section. Interestingly, average scores across groups indicated that the normal cervix is significantly more innervated (based on β-III tubulin IHC) than cervical carcinoma (p=3.98 ×10−7) yet contained significantly less TRPV1 staining (p=2.9×10−39)(Figure 2). When analyzed on a per sample basis, 35% of normal cervix samples had a β-III tubulin staining score of less than one, while 65% of samples had scores greater than one. The carcinoma cases were almost evenly divided between those scoring less than one and those scoring greater than one for β-III tubulin staining. Interestingly, while very few (7%) of the normal cervix samples had a TRPV1 score greater than one, 73% of the cervical cancer cases did (Table 1). These data indicate that innervation changes do indeed occur in the cervix during carcinogenesis.

Figure 2. Quantification of innervation.

Average IHC score of normal cervix (n= 10 cases) and cervical cancer (n=30 cases) for β-III tubulin and TRPV1. Statistical by unpaired student’s t-test, *, p< 0.05.

Table 1. Patient scores.

Percent of cases with β-III tubulin and TRPV1 IHC scores less than or greater than 1.

| Average Patient Score | <1 | >1 | <1 | >1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Cervix | 35% | 65% | 93% | 7% |

| Cervical Cancer | 60% | 40% | 27% | 73% |

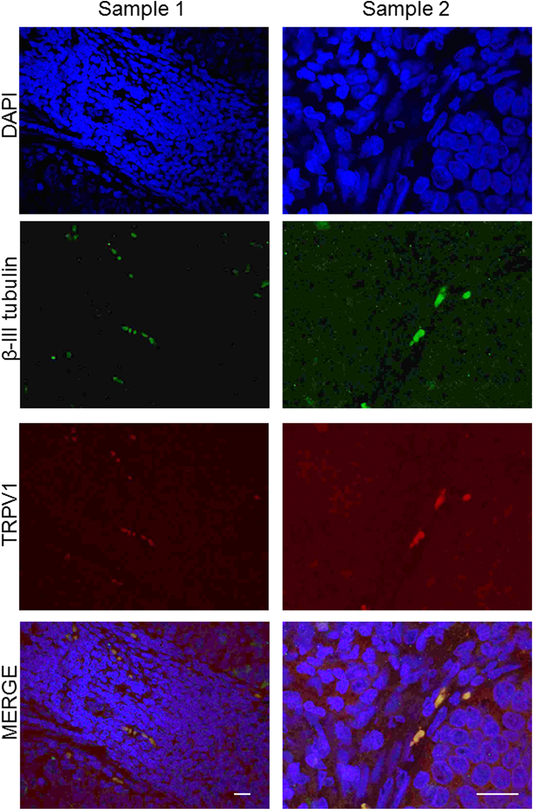

To further demonstrate this innervation, we immunofluorescently stained cervical cancer cases for β-III tubulin (green) and TRPV1 (red) (Figure 3). In all samples, there was clear co-localization of these neuronal markers (evidenced by yellow in the merged panel) further supporting the IHC data that cervical carcinomas are innervated with TRPV1 positive sensory nerves.

Figure 3: TRPV1 and β- III tubulin fibers co-localize in cervical cancer.

Representative en face confocal images of cervical cancer sections from different patient samples (samples 1 and 2) that were processed for double immunofluorescence to localize TRPV1 (red) and β-III tubulin (green) positive nerve twigs. The merged (yellow) images demonstrate the co-localization of the two markers. Sample 1 scale bar, 20 μm; Sample 2 scale bar, 10 μm. Nuclie counterstained with DaPi (blue).

Cervical Cancer-Derived Exosomes Induce Neurite Outgrowth

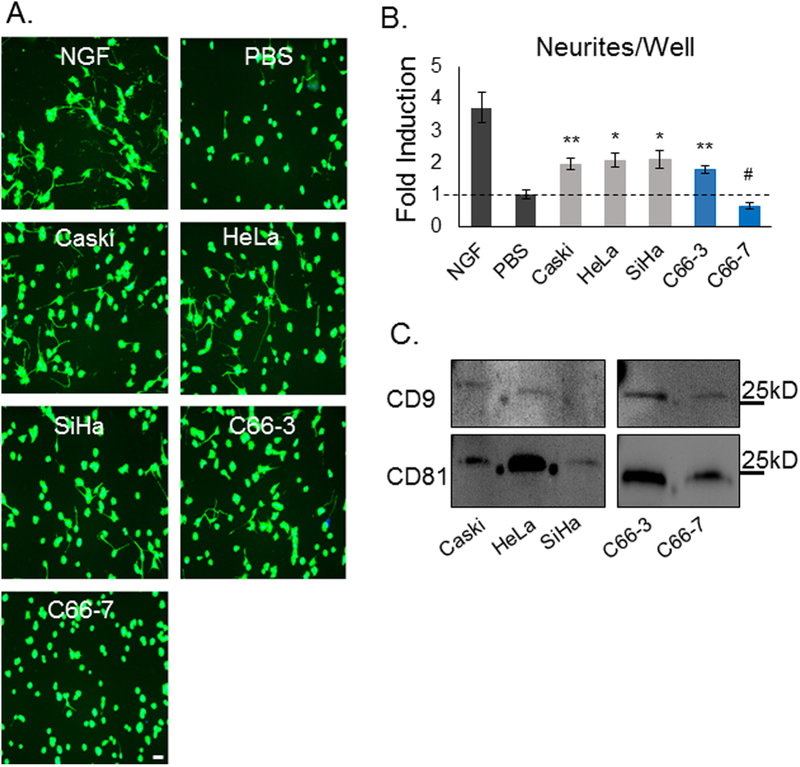

To test our hypothesis that cervical cancer-released exosomes promote tumor innervation, we isolated exosomes from several cervical cancer cell lines: Caski (strain: HPV 16; physical state of HPV DNA: integrated), HeLa (HPV18; integrated), SiHa (HPV16; integrated), C66–3 (HPV16; integrated), and C66–7 (HPV16, episomal) (10). Importantly, C66–3 and C66–7 are isogenic pairs that differ only by the integrated status of HPV. To investigate the ability of cervical cancer exosomes to induce neurite outgrowth, we utilized PC12 cells as surrogates for this activity. A pheochromocytoma- derived cell line, PC12 cells are commonly used to assess neuritogenic activity (16). With appropriate stimulation, e.g. nerve growth factor (NGF), PC12 cells reliably extend neurites. In the absence of such stimuli, they display a paucity of neurites. For our experiment, PC12 cells were incubated for 72-hours in the presence of exosomes purified from the conditioned media of the various cervical cancer cell lines. NGF (50 ng/μL) and PBS were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Following incubation, PC12 cells were fixed and fluorescently labeled for the neuronal marker, β-III tubulin (representative images, Figure 4A). β-III tubulin positive neurites were quantified using an automated platform as described in Methods. We observed consistent neurite outgrowth activity in exosomes from all cervical cancer cell lines, with the notable exception of exosomes derived from C66–7 cells, the lone cell line with episomal rather than integrated HPV (Figure 4A, B). Western blot analysis of exosomes for CD9 and CD81, exosomal markers, confirmed the purity of the exosomes utilized in this assay (Figure 4C).

Figure 4: Cervical cancer-derived exosomes induce neurite outgrowth.

(A) Representative fluorescent images of β-III tubulin staining (green) of PC12 cells treated with cervical cancer cell line derived exosomes. Scale bar, 20μm. (B) Quantitative PC12 neurite outgrowth assay results, showing both total neurites/well. Bars represent mean +/− SEM of n = 3 (exosome conditions), 6 (NGF), or 9 (PBS); *p < 0.05 vs. PBS alone; **p ≤ 0.005 vs. PBS alone; #p < 0.05 vs. all other cervical cancer exosomes. P-values reflect t-test results. (C) Western blot analysis of exosomes purified from the indicated cell lines for CD9 and CD81.

Discussion

In this study, we show the presence of sensory nerves within human cervical cancer specimens and, importantly, suggest a tumor-dependent exosome-mediated mechanism that may allow cervical carcinomas to induce their own innervation. Clinically, the extent of tumor innervation is inversely associated with patient prognosis in several different cancers (4–6). If a similar phenomenon occurs in cervical cancer, tumor-associated nerves and/or the process of exosome-mediated innervation may represent worthy therapeutic targets to improve outcomes in this patient population. Interestingly, our data show that β-III tubulin positive nerves are present in the stroma of the normal cervix. This localization suggests that tumor released exosomes diffuse loco-regionally, acting upon these nerves and promoting their extension towards the tumor parenchyma.

Our data also suggest that carcinogenesis alters cervical innervation. Interestingly, expression of β-III tubulin significantly decreases with carcinoma while that of TRPV1 significantly increases. At first blush, these data appear contradictory. How can there be more sensory innervation (TRPV1) when there are less nerves (β-III tubulin) present? Work by Shen and Yu sheds light on this conundrum. They found that hypoxia decreases expression of β-III tubulin and results in abnormal neuronal morphology (17). These findings are not limited to the central nervous system but extend into the peripheral nervous system (18). The hypoxic tumor microenvironment mediates many cellular changes in gene expression, signaling, metabolism, and angiogenesis (19–22). Thus, decreased IHC for β-III tubulin may reflect its decreased expression under hypoxic conditions present in cervical carcinomas; such a decrease may be beyond the limit of detection by IHC. Moreover, similar to angiogenic cancer associated blood vessels which are leaky, tortuous and abnormal, tumor-infiltrating nerves may be equally atypical, morphologically and structurally irregular, expressing low β-III tubulin and high TRPV1. Given that during development blood vessels and nerves follow parallel trajectories, a similarity in their phenotypes during carcinogenesis may not be so surprising. Moreover, the overwhelming majority of patients with cervical cancer present with significant pain (23). Our finding of significantly increased TRPV1 (a sensory nerve marker) expression with carcinogenesis is consistent with these clinical data.

Though beyond the scope of this work, future studies should include investigating the function of tumor-associated sensory nerves. In this regard, several notable, perhaps cooperative, phenomena may be at play. Most simply, locally-acting sensory nerve- released factors, e.g. substance P, may directly promote tumorigenic processes such as proliferation and survival as has been suggested in other cancers (24, 25). Additionally, a neuro-immune reflex arc has been described whereby activation of afferent sensory nerves by various inflammatory cytokines can modulate local or systemic immunity via the activity of efferent nerves (26, 27). Thus, it is possible that sensory innervation is indirectly tumorigenic via modulation of local or systemic anti-tumor immunity. Interestingly, immunotherapies like pembrolizumab (anti-PD1) are demonstrating promise for patients with advanced metastatic cervical cancer (28, 29). These positive responses indicate the presence of immune suppression that can be overcome with immunotherapy. The predominating rationale for testing immunotherapy in cervical cancer focuses on the role of the HPV virus in oncogenesis as viral antigens activate an immune response that can be boosted with immunotherapeutic approaches. If sensory innervation of cervical cancer modulates anti-tumor immunity, promoting immune suppression, our findings would not only provide additional support for the utility of immunotherapies in this setting but would also contribute a novel mechanistic understanding of their efficacy.

Interestingly, while further investigation is clearly warranted, the data suggest that the phenomenon of cervical cancer-derived exosome-mediated neurite outgrowth may be dependent on the integration status of HPV. Recent studies indicate that upwards of 80% of all HPV-positive cervical cancers show evidence of HPV DNA integration into the host genome (30, 31). Moreover, several studies have noted worse clinical outcomes in patients with integrated HPV, suggesting prognostic value (31, 32). In light of the data presented here, it remains possible that potentiation of exosome-mediated innervation contributes to poor prognosis in this patient population. Integration of HPV DNA is associated with dysregulation of viral oncogene expression and disruption of the host genome at the site of integration, occasionally altering the expression of oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes (33), either or both of which could alter the content and/or function of exosomes. Indeed, silencing of the HPV viral oncogenes E6 and E7 in HeLa cells significantly alters both exosome content and release (34, 35). Thus, the role of HPV integration in exosome-mediated neurite outgrowth merits significant consideration moving forward.

Highlights.

Exosomes from cervical cancer cell lines with integrated HPV promote neurite outgrowth of PC12 cells

Exosomes from cervical cancer cell lines with episomal HPV fail to promote neurite outgrowth of PC12 cells

Cervical cancers are innervated with sensory nerves

The integrated HPV status of cervical cancer may modulate tumor innervation mediated by tumor-released exosomes

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (5P20GM103548–08), the Molecular Pathology and Imaging cores at Sanford Research supported by 5P20GM103548, P20GM103620 and the Ovarian Cancer Translational Center of Excellence at the Penn Medicine’s Abramson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure/Conflicts of Interest

RD serves on the scientific advisory boards of Siamab Therapeutics, Inc and Repare Therapeutics, Inc.

PDV has a patent pending on EphrinB1 in tumor control and a licensing agreement with NantHealth for an HPV vaccine.

All authors have approved the final article.

References

- 1.Ault KA. Epidemiology and natural history of human papillomavirus infections in the female genital tract. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2006;2006 Suppl:40470. doi: 10.1155/IDOG/2006/40470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gynecologic Cancers: Cervical Cancer Statistics: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/statistics/index.htm.

- 3.St Laurent J, Luckett R, Feldman S. HPV vaccination and the effects on rates of HPV-related cancers. Current Problems in Cancer. 2018;42(5):493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabben HL, et al. Vagotomy and Gastric Tumorigenesis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016;14(8):967–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnon C, Hall SJ, Lin J, Xue X, Gerber L, Freedland SJ, Frenette PS. Autonomic Nerve Development Contributes to Prostrate Cancer Progression. Science. 2013;341(6142):1236361. doi: 10.1126/science.1236361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayala GE, Dai H, Powell M, Li R, Ding Y, Wheeler TM, Shine D, Kadmon D, Thompson T, Miles BJ, Ittmann MM, Rowley D. Cancer-related axonogenesis and neurogenesis in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(23):7593–603. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Streiter S, et al. The importance of neuronal growth factors in the ovary. Mol Hum Reprod. 2016;22(1):3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Entschladen F, et al. Neoneurogenesis: tumors may intiate their own innervation by the release of neurotrophic factors in analogy to lymphangiogenesis and neoangiogenesis. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67(1):33–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madeo M, Colbert PL, Vermeer DW, Lucido CT, Cain JT, Vichaya EG, Grossberg AJ, Muirhead D, Rickel AP, Hong Z, Zhao J, Weimer JM, Spanos WC, Lee JH, Dantzer R, Vermeer PD. Cancer exosomes induce tumor innervation. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4284. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06640-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Yi SM, Anderson ME, Berger KL, Welsh MJ, Klingelhutz AJ, Ozbun MA. Propagation of infectious human papillomavirus type 16 by using an adenovirus and Cre/LoxP mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(7):2094–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308615100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical C. Comparison of risk factors for invasive squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 8,097 women with squamous cell carcinoma and 1,374 women with adenocarcinoma from 12 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(4):885–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Argiris A, Karamouzis MV, Raben D, Ferris RL. Head and neck cancer. The Lancet. 2008;371(9625):1695–709. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60728-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stjernholm Y, Sennstrom M, Granstrom L, Ekman G, Johansson O. Protein gene product 9.5-immunoreactive nerve fibers and cells in human cervix of late pregnant, postpartal and non-pregnant women. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 1999;78(4):299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahebali S, Van den Eynden G, Murta EF, Michelin MA, Cusumano P, Petignat P, Bogers JJ. Stromal issues in cervical cancer: a review of the role and function of basement membrane, stroma, immune response and angiogenesis in cervical cancer development. European journal of cancer prevention : the official journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation. 2010;19(3):204–15. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32833720de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gius D, Funk MC, Chuang EY, Feng S, Huettner PC, Nguyen L, Bradbury CM, Mishra M, Gao S, Buttin BM, Cohn DE, Powell MA, Horowitz NS, Whitcomb BP, Rader JS. Profiling microdissected epithelium and stroma to model genomic signatures for cervical carcinogenesis accommodating for covariates. Cancer research. 2007;67(15):7113–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrill JA, Mundy WR. Quantitative assessment of neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Methods in Molecular Biology (Methods and Protocols). 2011;758:331–48. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-170-3_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen Y, Yu LC. Potential protection of curcumin against hypoxia-induced decreases in beta-III tubulin content in rat prefrontal cortical neurons. Neurochemical research. 2008;33(10):2112–7. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9720-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clayton BL, Huang A, Dukala D, Soliven B, Popko B. Neonatal Hypoxia Results in Peripheral Nerve Abnormalities. The American journal of pathology. 2017;187(2):245–51.doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parks SK, Cormerais Y, Pouyssegur J. Hypoxia and cellular metabolism in tumour pathophysiology. The Journal of physiology. 2017;595(8):2439–50. doi: 10.1113/JP273309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu W, Hu Q, Nie E, Yu T, Wu Y, Zhi T, Jiang K, Shen F, Wang Y, Zhang J, You Y. Hypoxia induces H19 expression through direct and indirect Hif-1alpha activity, promoting oncogenic effects in glioblastoma. Scientific reports. 2017;7:45029. doi: 10.1038/srep45029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strzyz P Cancer biology: Hypoxia as an off switch for gene expression. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2016;17(10):610. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rey S, Schito L, Wouters BG, Eliasof S, Kerbel RS. Targeting Hypoxia-Inducible Factors for Antiangiogenic Cancer Therapy. Trends in cancer. 2017;3(7):529–41. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim YJ, Munsell MF, Park JC, Meyer LA, Sun CC, Brown AJ, Bodurka DC, Williams JL, Chase DM, Bruera E, Ramondetta LM. Retrospective review of symptoms and palliative care interventions in women with advanced cervical cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 2015;139(3):553–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.09.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma J, Yuan S, Cheng J, Kang S, Zhao W, Zhang J. Substance P Promotes the Progression of Endometrial Adenocarcinoma. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2016;26(5):845–50. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munoz M, Covenas R. Involvement of substance P and the NK-1 receptor in pancreatic cancer. World journal of gastroenterology. 2014;20(9):2321–34. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i9.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olofsson PS, Rosas-Ballina M, Levine YA, Tracey KJ. Rethinking inflammation: neural circuits in the regulation of immunity. Immunol Rev. 2012;248(1):188–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Verri WA Jr., Chiu IM. Nociceptor Sensory Neuron-Immune Interactions in Pain and Inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2017;38(1):5–19. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kranawetter M, Rohrich S, Mullauer L, Obermair H, Reinthaller A, Grimm C, Sturdza A, Kostler WJ, Polterauer S. Activity of Pembrolizumab in Recurrent Cervical Cancer: Case Series and Review of Published Data. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2018;28(6):1196–202. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borcoman E, Le Tourneau C. Pembrolizumab in cervical cancer: latest evidence and clinical usefulness. Therapeutic advances in medical oncology. 2017;9(6):431–9. doi: 10.1177/1758834017708742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Integrated genomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017;543(7645):378–84. doi: 10.1038/nature21386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das P, Thomas A, Kannan S, Deodhar K, Shrivastava SK, Mahantshetty U, Mulherkar R. Human papillomavirus (HPV) genome status & cervical cancer outcome--A retrospective study. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142(5):525–32. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.171276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koneva LA, Zhang Y, Virani S, Hall PB, McHugh JB, Chepeha DB, Wolf GT, Carey TE, Rozek LS, Sartor MA. HPV Integration in HNSCC Correlates with Survival Outcomes, Immune Response Signatures, and Candidate Drivers. Molecular Cancer Research. 2018;16(1):90–102. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0153; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McBride AA, Warburton A. The role of integration in oncogenic progression of HPV-associated cancers. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(4):e1006211. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Honegger A, Leitz J, Bulkescher J, Hoppe-Seyler K, Hoppe-Seyler F. Silencing of human papillomavirus (HPV) E6/E7 oncogene expression affects both the contents and the amounts of extracellular microvesicles released from HPV-positive cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(7):1631–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Honegger A, Schilling D, Bastian S, Sponagel J, Kuryshev V, Sultmann H, Scheffner M, Hoppe-Seyler K, Hoppe-Seyler F. Dependence of intracellular and exosomal microRNAs on viral E6/E7 oncogene expression in HPV-positive tumor cells. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(3):e1004712. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]