Abstract

Major depressive disorder begins to increase in early adolescence and is associated with significant impairment (e.g., suicidality). Difficulties in emotion regulation (ER) have been associated with depressive symptoms; however, little research has examined this relation over time beginning in early adolescence. Starting when they were 11-14 years old, 246 adolescents (nboys = 126; nwhite = 158) completed self-report questionnaires on their ER at Time 1 and depressive symptoms every year for 2 years. Results revealed that overall difficulties in ER (and limited access to ER strategies) at Time 1 predicted depressive symptoms both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Gender moderated this relation cross-sectionally, such that higher overall ER difficulties at Time 1 was more strongly associated with higher depressive symptoms for girls than for boys. These findings suggest that depression prevention efforts should promote adaptive ER in early adolescence, particularly for girls, in order to prevent the increases in depressive symptoms seen into middle adolescence.

Keywords: emotion regulation, adolescents, depressive symptoms, longitudinal

Major depressive disorder increases sharply from early to middle adolescence, with 12-month prevalence rates nearly doubling from age 13 (4.5%) to 16 (8.7%) [1]. This increase is of great societal concern given the consequences of major depressive disorder. Adolescents with major depressive disorder are more likely to attempt suicide, take impulsive risks (e.g., unsafe sex), and engage in substance use [2–4]. These consequences also occur with subclinical levels depressive symptoms [5, 6]. Given the widespread implications of adolescent major depressivf disorder, it is imperative to understand what contributes to depressive symptomology. Difficulties in emotion regulation (ER) are a potential risk factor for depressive symptoms tha have been the subject of extensive empirical investigation. Difficulties in ER have been linked depressive symptoms and other internalizing symptoms in adolescence [7]; however, less longitudinal research has been conducted on this relation in the transition from early to middle adolescence. It is important to understand this longitudinally in order to identify what types of ER difficulties are present in early adolescence prior to the escalation of depressive symptoms into middle adolescence.

In addition, when examining the effects of ER difficulties on depressive symptoms it is important to examine gender moderation. Starting in early adolescence and continuing into adulthood, twice as many girls as boys are diagnosed with a depressive disorder [8]. Girls also show higher levels of depressive symptoms during early adolescence [9]. Furthermore, studies have suggested that ER may differ by gender, with women and girls reporting greater emotion reactivity [10], greater emotion expressivity [11], and different use of some ER strategies than men and boys [12]. Thus, it is important to be sensitive to gender when examining emotion-related predictors of depressive symptoms. The present study examined difficulties in ER predicting longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms from early adolescence to middle adolescence and examined whether ER pathways differed for boys and girls.

Emotion Regulation

ER is the ability to modify the expression, experience, and physiology of an emotion to meet situational demands [13]. Difficulties in ER occur with a breakdown in any of these components. If a person has ongoing difficulties in ER, psychosocial impairment can result [12]. This is particularly true in early adolescence. Starting in early adolescence, youth experience a host of puberty-related physical (i.e., increased sex hormones, body changes) and social changes (e.g., increased importance of peers versus parental figures) that are stressful [14]. These stressful developmental changes require that adolescents tax their still-developing ER skills. It is not until later adolescence and early adulthood that use ER becomes more sophisticated (e.g., increased repertoire of ER strategies) and more effectively used [15]. These developmental limitations in ER put adolescents at increased risk of depressive symptoms.

Indeed, self-reported difficulties in ER have been linked cross-sectionally to depressive symptoms in early, middle, and late adolescence [16–18]. High levels of negative emotional expression, a possible indicator of difficulties regulating emotion, have also been linked to depressive symptoms [19, 20]. In addition, a few studies have shown that difficulties in ER predict depressive symptoms longitudinally from childhood to pre-adolescence [19, 21], and in one shorter-term longitudinal study over one year during early adolescence [7]. To our knowledge, no study has examined the relation between difficulties in ER and depressive symptoms across longer durations of time (i.e., greater than 1 year) in the early to middle adolescent developmental period (a critical period for the development of major depressive disorder). Even fewer studies have examined specific ER difficulties and how they are related to depressive symptoms. Difficulties in ER can refer to several processes: lack of emotional awareness, lack of emotional clarity, nonacceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, impulse control difficulties, and limited access to ER strategies [22].

First, an adolescent may be unaware of their emotions and/or have difficulty understanding their emotions. As a result of these difficulties, the adolescent may not be able to engage in further ER, as doing so involves knowing what to modify. This pattern could lead the adolescent to experience high negative emotion that may become chronic over time [16, 23]. Empirically, a lack of emotional awareness and emotional clarity have been cross-sectionally associated with depressive symptoms in adolescents [18, 24]. Rieffe and De Rooiji [25] also found that the inability to identify emotions prospectively predicted depressive symptoms six months later in late childhood. One longitudinal study has also linked lack of emotional clarity to depressive symptoms among early adolescents [26].

Second, an adolescent may have emotional awareness and clarity, but be unwilling to accept their emotional response. An unwillingness to accept negative emotion may lead adolescents to suppress emotions, which may then lead to an amplification of negative emotion [27–29]. For instance, an adolescent may suppress feelings of sadness related to a loss of a friendship which may increase sadness over the long-term. Neumann et al. [18] found that nonacceptance of emotional responses was cross-sectionally related to depressive symptoms among early, middle, and late adolescents. To our knowledge, no longitudinal research has been conducted on the relation between nonacceptance of emotional responses and depressive symptoms in adolescents.

Third, although negative emotion can sometimes be adaptive, other times negative emotion may leave an adolescent unable to engage in goal-directed behaviors. For example, an adolescent may be unable to do everyday tasks, such as chores and studying for an important test, while experiencing sadness over a breakup. Recent research reveals that the inability to engage in goal-directed behaviors during a negative emotional state is a longitudinal predictor of depressive symptoms in adolescents and preadolescents [30]. Similar to an inability to engage in goal-directed behavior, an adolescent may engage in rash, impulsive behavior in response to negative emotion. Impulsive behavior in response to negative emotion has been cross-sectionally related to the development of depressive symptoms among early, middle, and late adolescents [31]. Other studies have shown that impulsive behavior in response to negative emotion, such as risky sex and substance use, predicts depressive symptoms in early, middle, and late adolescence over a one-year span [32].

Finally, an adolescent may lack access to strategies needed to modulate negative emotion. For example, an adolescent may know they are sad, but may not know how to effectively down-regulate sadness (e.g., cognitive reappraisal). The result of this is that adolescents have to either refrain from ER entirely or rely on maladaptive ER strategies, such as rumination [33]. In both cases, negative emotion cannot be down-regulated and may become chronic [16, 23]. This limited access to ER strategies has been cross-sectionally associated with depressive symptoms [18]. Other studies have shown that adolescents with major depressive disorder have difficulty thinking of adaptive strategies and utilizing them for regulatory purposes. For example, they are less likely to use reappraisal (i.e., modification of thoughts), problem-solving (i.e., taking action to resolve source of conflict), and other adaptive strategies to cope with negative emotion [28]. Extant literature has not examined limited access to ER strategies as a longitudinal predictor of depressive symptoms among adolescents.

Altogether, these results make clear that a variety of ER difficulties are related to depressive symptoms. In most of these ER difficulties, adolescents may experience sustained levels of negative emotion, which may make it more likely that they will suffer from chronic negative emotion such as major depressive disorder [16, 23]. It is worth noting, however, that few of these studies examined several ER difficulties within one study across the period of early adolescence to middle adolescence. Most studies have been conducted on adults or preadolescents, and even fewer have examined these relations utilizing longitudinal designs. Longitudinal research allows us to investigate how ER difficulties affect the trajectory of depressive symptoms over time throughout adolescence.

Gender Considerations

Gender is important to examine given the gender differences in rates of major depressive disorder and depressive symptoms starting in early adolescence, with adolescent girls showing higher depressive symptoms than boys [8]. Up until age 13, boys and girls have comparable levels of major depressive disorder—it is not until puberty that these gender differences emerge. These findings have been replicated over decades of research and are also true when looking at subthreshold symptoms and clinical levels of major depressive disorder [14].

Gender is also important to consider because there are gender differences across several domains of emotional functioning: reactivity, expression, and regulation, likely due to a combination of biological sex differences in emotionality and gender-role socialization. Girls self-report higher levels of negative emotional reactivity [10]; other studies have also shown that girls also experience greater sympathetic nervous system reactivity to stressful events than boys in early, middle, and late adolescence [34, 35]. In regards to emotional expression, girls show higher levels of negative emotion expression than boys (particularly for sadness and anxiety-related emotions) in childhood and adolescence [11]. Girls may also engage more frequently in specific maladaptive ER strategies such as rumination, which has been found to be highly predictive of depressive symptoms [36]. There is also mixed evidence to suggest that boys may show more difficulty with emotional awareness and clarity than girls, with some studies showing that boys are more challenged when distinguishing between anger and sadness [18, 37]. However, other studies have also shown that girls have more difficulty with emotional clarity [18]. Thus, highlighting the need for further research examining the associations between gender and specific difficulties in ER.

In addition to gender differences in ER, ER difficulties may be more predictive of depressive symptoms in girls than boys. Due to an earlier onset of puberty, girls experience more puberty-related stressors (e.g., sexual harassment, body dissatisfaction etc.) during early adolescence compared to boys leaving them more vulnerable to the development of depressive symptomatology [14]. Since boys may experience fewer puberty-related stressors, any ER difficulties may be less likely to lead to depressive symptoms. Boys may also have a different pathway to depressive symptoms that does not involve ER difficulties. For example, alterations in reward sensitivity may be a stronger pathway to depressive symptoms for boys [38].

Current Study

The current study examined self-reported ER difficulties as a predictor of depressive symptoms cross-sectionally during early adolescence and longitudinally over a two-year span from early to middle adolescence. We also examined gender as a moderator of these relations. Further analyses were conducted to uncover the specific ER difficulties underlying cross-sectional and longitudinal relations to depressive symptoms. Our hypotheses were as follows: 1) overall difficulties in ER at Time 1 will predict higher depressive symptoms cross-sectionally and longitudinally over two years, 2) gender will moderate this association, such that ER difficulties at Time 1 will be a stronger predictor of depressive symptoms among girls than boys cross-sectionally and longitudinally over two years, (3) we will also explore which types of ER difficulties at Time 1 (i.e., lack of emotional awareness, lack of emotional clarity, nonacceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, impulse control difficulties, and limited access to ER strategies) predict depressive symptoms cross-sectionally and longitudinally over two years. We hypothesize that limited access to ER strategies at Time 1 may be particularly important in predicting depressive symptoms, as it impairs the ability to down-regulate negative emotion and subsequently the ability to respond to stressors. (4) We will also explore whether there is gender moderation for each of the ER difficulties at Time 1 cross-sectionally and longitudinally over two years. No a priori hypotheses were developed regarding the effect of gender differences on the associations between specific ER difficulties and depressive symptoms, given the limited existing literature in this area.

Method

Participants

Subjects were 246 early adolescents (M = 12.61, Range of age: 11 to 14, SD = .64; 126 boys, 51%) enrolled in a longitudinal study on gender, emotion, and the development of substance use and psychopathology. Subjects were recruited from two northeastern metropolitan areas. All subjects were recruited from the community with fliers and mailings. The sample of subjects were representative of their communities, with 64.5% Non-Hispanic White, 10.1% Black, 2.4% Asian, 9.3% Hispanic, 8.1% Biracial, and 2.8% other. Inclusion criteria for the adolescent were age 11-14 years, IQ >= 80, and adequate English proficiency to complete questionnaires. Exclusion criteria were history of prenatal substance exposure, autism spectrum disorder, and psychotic disorder for the adolescent.

Adolescents attended sessions at Time 1, six months later, and then once per year for the next two years. The present study used Time 1 data, 1-year follow-up data (referred to as “Time 2”), and 2-year follow-up data (referred to as “Time 3”). Six-month data was not used because it was close in time to Time 1 data. Adolescents completed self-report questionnaires at each timepoint. In addition, parents provided demographic information about their adolescent. Adolescents were able to complete all assessments in a private room. The parent and adolescent were monetarily compensated for their time. All study procedures were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) [22].

The DERS is a 36-item self-report questionnaire used to assess levels of ER difficulties in adolescents. It includes six subscales that reflect the various dimensions of ER difficulties: lack of emotional awareness (AWAR; e.g., “I pay attention to how I feel”), lack of emotional clarity (EC; e.g., “I have difficulty making sense out of my feelings”), nonacceptance of emotional responses (NER; e.g., “When I’m upset, I feel guilty for feeling that way”), difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior (GDB; e.g., “When I’m upset, I have difficulty getting work done”), impulse control difficulties (IMP; e.g., “When I’m upset, I become out of control”), and limited access to ER strategies (STRAT; e.g., “When I’m upset, I believe that I’ll end up feeling very depressed”). Adolescents are told to rate the extent to which they experience the sentiments in the past year on a five-point scale, from “almost never” to “almost always.” The DERS has good construct and predictive validity with other ER scales [22]. In addition, it has been shown to be reliable within a wide variety of samples, including adolescents [18]. Scores were computed for all subscales; a total score was computed by summing up all the subscale scores. Higher total scores reflect greater difficulty in regulating emotions. Internal consistency for the total score in the current sample at Time 1 was α = .93. The individual subscales had the following Chronbach’s alpha at Time 1: .82 for AWAR, .77 for EC, .86 for NER, .85 for GDB, .86 for IMP, and .86 for STRAT. Only Time 1 DERS was used in the current analyses, given our a priori hypotheses that Time 1 DERS would predict the trajectory of depressive symptoms.

Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) [39].

The CDI is a 27-item self-report scale used to assess severity of symptoms of depression in adolescents. Adolescents are told to select one of three response items that best match their experiences in the past two weeks (e.g., “I am sad once in a while,” “I am sad many times,” and “I am sad all the time”). The CDI has been shown to have high internal reliability, test-retest reliability, and discriminant validity [37]. Internal consistency in the current samples was α = .90 for Time 1, α = .91 for Time 2, and α = .90 for Time 3. Fifteen of the 248 youth (i.e., 6%) at Time 1 had clinical levels of depressive symptoms based on the CDI cutoff of 20 [37, 40]. This is consistent with other studies on depressive symptoms in community samples [41].

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were examined, and then preliminary analyses were conducted examining associations among adolescent gender, ER difficulties, and depressive symptoms at each time point. Next, data was examined for assumptions of the general linear model. Using SPSS, we performed multiple regression to examine cross-sectional data at Time 1. A model was created with Time 1 overall ER difficulties and gender as main effects, and Time 1 overall ER difficulties X gender interaction predicting depressive symptoms at Time 1. Separate models were created for each subscale of the DERS, resulting in a total of six models. All continuous predictors were mean-centered prior to inclusion in the models. Main effects and interaction p-values for ER difficulties subscale follow-ups were Bonferonni corrected. The critical p-value for individual tests was .008, thus resulting in a family-wise alpha of .05.

A growth model was also created to account for the three time points spaced approximately 1 year apart nested within each adolescent. Specifically, we performed a series of multilevel models using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) – Version 7 [42]. Multilevel modeling is able to handle missing data associated with not having an outcome measurement for each person at each time point [43].

We first specified a two-level unconditional means model, with three depressive symptom time points nested with each adolescent, to examine the proportion of variance in depressive symptom scores attributed to within- and between-adolescent variance. Then, we examined an unconditional growth model to examine the linear effect of time on adolescent depressive symptoms, in which time was entered as a level 1 predictor (entered 0, 1, and 2). This model included random effects for both the intercept (initial level of depressive symptoms) and the linear slope of depressive symptoms for each adolescent. Next, we constructed a series of conditional growth models, in which the linear effects of Time 1 overall ER difficulties, gender, and the interaction between Time 1 overall ER difficulties and gender on adolescent depressive symptom trajectories were examined. Finally, to examine the effects of specific ER difficulties, we constructed conditional growth models separately including each DERS subscale at Time 1 and their interaction with gender, resulting in a total of six models. Again, main effects and interaction p-values for ER difficulties subscale follow-ups were Bonferonni corrected (critical p-value for individuals tests = .008). Continuous variables (i.e., ER difficulties) in conditional growth models were grand mean-centered.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Bivariate correlations among primary study variables (ER difficulties, depressive symptoms) are reported in Tables 1 and 2 for boys and girls separately. Descriptive statistics, along with t-tests to detect differences among primary study variables between girls and boys are reported on Table 3. Girls had significantly higher depressive symptoms at each time point, as well as higher overall ER difficulties at Time 1 compared to boys. In addition, overall ER difficulties were positively correlated with depressive symptoms at each time point for both boys and girls. To examine potential covariates for the primary analyses, bivariate correlations were examined among primary study variables and demographic variables (e.g., race, age). These demographic variables were not significantly associated with any of the primary study variables and thus were not included as covariates.

Table 1.

Correlations for Girls

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DERS | ||||||||||

| 1. Overall DERS | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2. AWAR | .45*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3. EC | .78*** | .42*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 4. NER | .79*** | .18 | .57*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 5. IMP | .76*** | .16 | .42*** | .56*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 6. GDB | .67*** | .06 | .39*** | .38*** | .47*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 7. STRAT | .90*** | .21* | .70*** | .74*** | .64*** | .58*** | 1.00 | |||

| CDI | ||||||||||

| 8. CDI – Time 1 | .71*** | .49*** | .70*** | .55*** | .42*** | .31** | .64*** | 1.00 | ||

| 9. CDI – Time 2 | .49*** | .37*** | .52*** | .31*** | .23* | .24* | .50*** | .66*** | 1.00 | |

| 10. CDI – Time 3 | .44*** | .21* | .41*** | .36*** | .36*** | .21* | .41*** | .49*** | .58*** | 1.00 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Note. DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, AWAR = Lack of Emotional Awareness, EC = Lack of Emotional Clarity, NER = Nonacceptance of Emotional Responses, IMP = Impulse Control Difficulties, GDB = Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behavior, STRAT = Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies, CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory

Table 2.

Correlations for Boys

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DERS | ||||||||||

| 1. Overall DERS | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2. AWAR | .50*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3. EC | .64*** | .53*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 4. NER | .66*** | −.017 | .25** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 5. IMP | .80*** | .23** | .34*** | .46*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 6. GDB | .69*** | .11 | .28** | .37*** | .58*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 7. STRAT | .84*** | .14 | .41*** | .70*** | .67*** | .52*** | 1.00 | |||

| CDI | ||||||||||

| 8. CDI – Time 1 | .60*** | .40*** | .45*** | .38*** | .42*** | .31** | .53*** | 1.00 | ||

| 9. CDI – Time 2 | .36*** | .20* | .22* | .30*** | .19* | .13 | .39*** | .42*** | 1.00 | |

| 10. CDI – Time 3 | .20* | .15 | .17 | .08 | .18 | .09 | .12 | .33** | .42*** | 1.00 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Note. DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, AWAR = Lack of Emotional Awareness, EC = Lack of Emotional Clarity, NER = Nonacceptance of Emotional Responses, IMP = Impulse Control Difficulties, GDB = Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behavior, STRAT = Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies, CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory

Table 3.

Means of Key Measures for Boys and Girls

| Girls |

Boys |

t-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| DERS | |||||

| 1. Overall DERS | 76.19 | 22.20 | 70.24 | 18.55 | −.15* |

| 2. AWAR | 14.88 | 4.96 | 15.97 | 5.44 | ns |

| 3. EC | 10.06 | 3.84 | 8.71 | 2.95 | −.20** |

| 4. NER | 11.33 | 4.97 | 9.84 | 4.29 | −.16* |

| 5. IMP | 11.21 | 5.07 | 10.27 | 4.49 | ns |

| 6. GDB | 13.35 | 5.11 | 12.01 | 4.60 | −.14* |

| 7. STRAT | 15.37 | 6.43 | 13.46 | 5.16 | −.16* |

| CDI | |||||

| 8. CDI – Time 1 | 8.79 | 8.32 | 5.18 | 4.75 | −.26*** |

| 9. CDI – Time 2 | 9.66 | 8.61 | 4.71 | 4.92 | −.34*** |

| 10. CDI – Time 3 | 9.90 | 8.45 | 4.89 | 4.58 | −.35*** |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Note. DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, AWAR = Lack of Emotional EC = Lack of Emotional Clarity, NER = Nonacceptance of Emotional Responses, IMP = Impulse Control Difficulties, GDB = Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behavior, STRAT = Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies, CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory

No missing data were present at Time 1 (246 adolescents); however, 9.76% percent of adolescents at Time 2 (i.e., 222 adolescents) and 14.2% percent of adolescents at Time 3 (i.e., 211 adolescents) were missing data due to attrition. Most missing occasions were due to scheduling difficulties. Adolescents with missing data did not differ on gender, race, or age (p’s > .05). Data did not violate any major assumptions of the general linear model (i.e., normality and homoscedasticity).

Cross-Sectional Analyses of Adolescent Depressive Symptoms

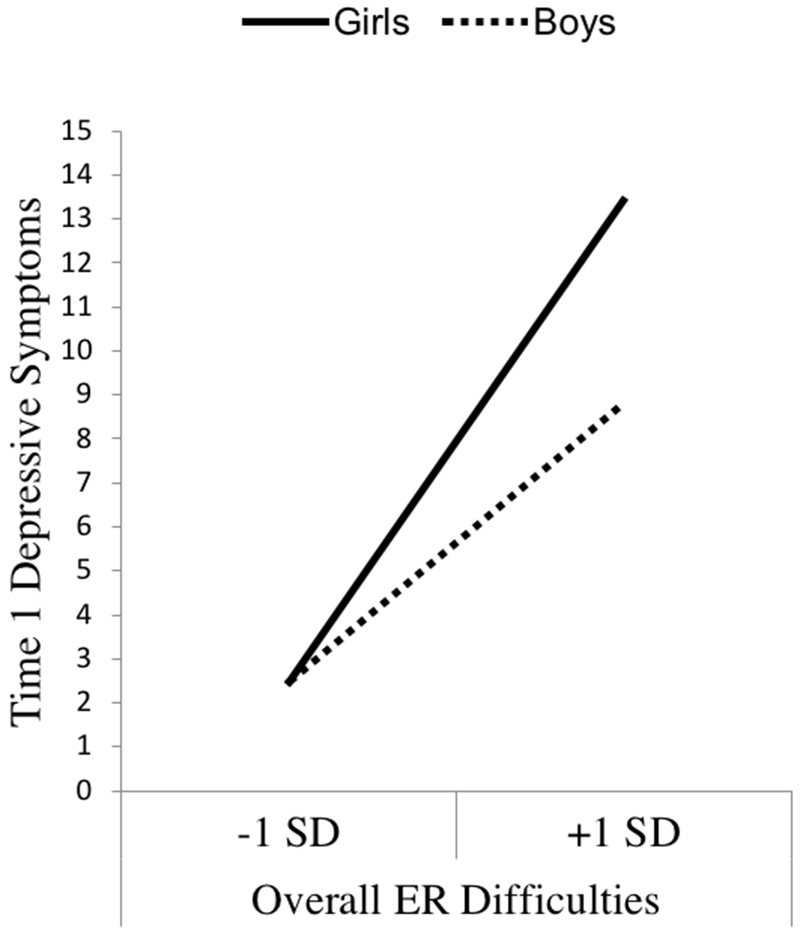

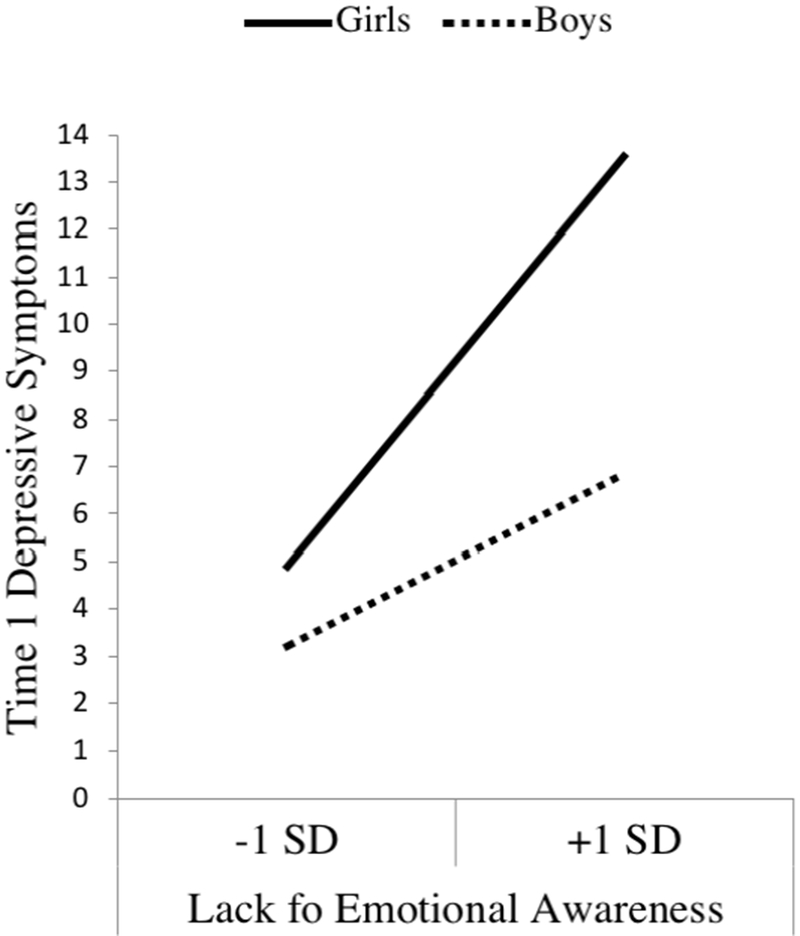

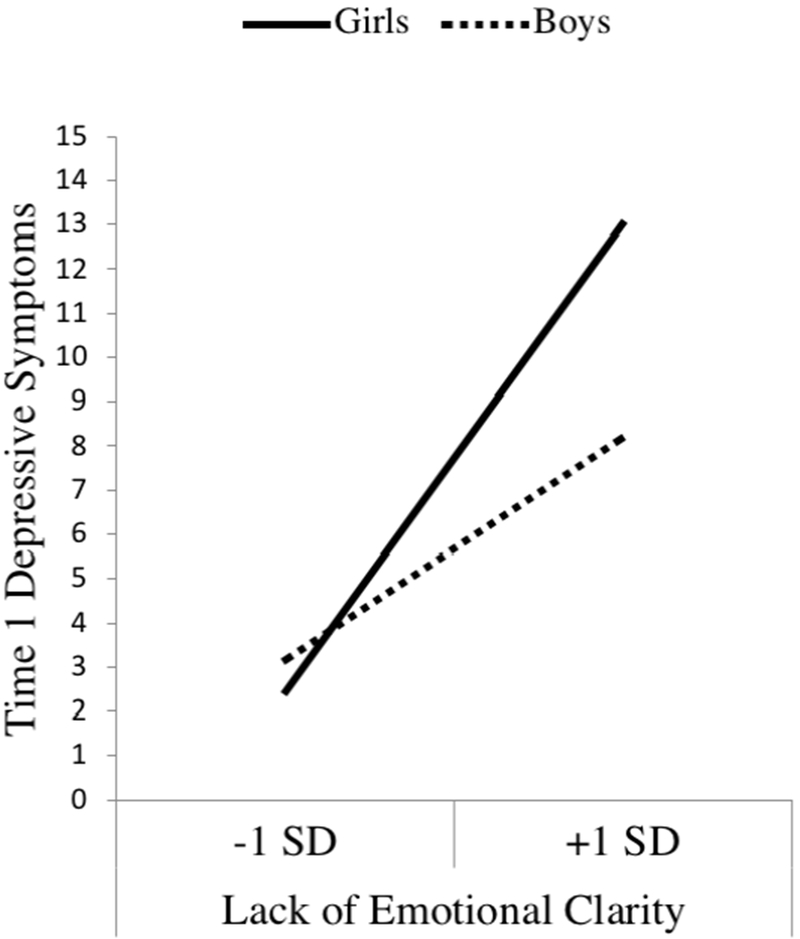

Overall ER difficulties at Time 1 was associated with increased depressive symptoms at Time 1 (B = .21, SE = .02, p < .001). Gender moderated this relation, with ER difficulties at Time 1 more strongly associated with depressive symptoms at Time 1 among girls, B = −.11, SE = .04, p < .05 (see Figure 1). Next, we examined prediction of depressive symptoms at Time 1 from the six ER difficulties subscales (lack of emotional awareness, lack of emotional clarity, nonacceptance of emotional responses, impulse control difficulties, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, and limited access of ER strategies) at Time 1, with Bonferroni correction. All six of the ER difficulties subscales at Time 1 were significant predictors of higher levels of depressive symptoms at Time 1 (p’s < .001) (see Table 4). Gender moderated these relations for two ER difficulties subscales: lack of emotional clarity and lack of emotional awareness. For this, lack of emotional clarity and lack of emotional awareness at Time 1 were more strongly associated with depressive symptoms among girls at Time 1 (see Figures 2 and 3). Gender did not significantly moderate the relation for the other four ER difficulties subscales.

Figure 1.

Simple slopes of gender predicting depressive symptoms for 1 SD below the mean of overall ER difficulties, and 1 SD above the mean of overall ER difficulties.

Table 4.

Difficulties in ER Predicting Depressive Symptoms at Time 1

| Variable | B | SE | Uncorrected p value | Corrected p value | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Model | |||||

| Gender | −2.30 | .63 | <.001*** | - | - |

| Overall DERS | .21 | .02 | <.001*** | - | - |

| Overall DERS × Gender | −.11 | .04 | .01* | - | .03 |

| Model 1: AWAR | |||||

| AWAR | .58 | .08 | <.001*** | <.001*** | - |

| AWAR × Gender | −.48 | .16 | .004** | .02* | .03 |

| Model 2: EC | |||||

| EC | 1.11 | .14 | <.001*** | <.001*** | - |

| EC × Gender | −.80 | .28 | .004** | .02* | .04 |

| Model 3: NER | |||||

| NER | .67 | .12 | <.001*** | <.001*** | - |

| NER × Gender | −.51 | .24 | .03* | .19 | .03 |

| Model 4: IMP | |||||

| IMP | .57 | .11 | <.001*** | <.001*** | - |

| IMP × Gender | −.26 | .22 | .25 | 1 | .01 |

| Model 5: GDB | |||||

| GDB | .40 | .09 | <.001*** | <.001*** | - |

| GDB × Gender | −.18 | .18 | .33 | 1 | .00 |

| Model 6: STRAT | |||||

| STRAT | .66 | .08 | <.001*** | <.001*** | - |

| STRAT × Gender | −.35 | .17 | .04* | .22 | .02 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Note. DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, AWAR = Lack of Emotional Awareness, EC = Lack of Emotional Clarity, NER = Nonacceptance of Emotional Responses, IMP = Impulse Control Difficulties, GDB = Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behavior, STRAT = Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies.

Figure 2.

Simple slopes of gender predicting depressive symptoms for 1 SD below the mean of lack of emotional awareness, and 1 SD above the mean of lack of emotional awareness.

Figure 3.

Simple slopes of gender predicting depressive symptoms for 1 SD below the mean of lack of emotional clarity, and 1 SD above the mean of lack of emotional clarity.

Multilevel Modeling of Adolescent Depressive Symptoms

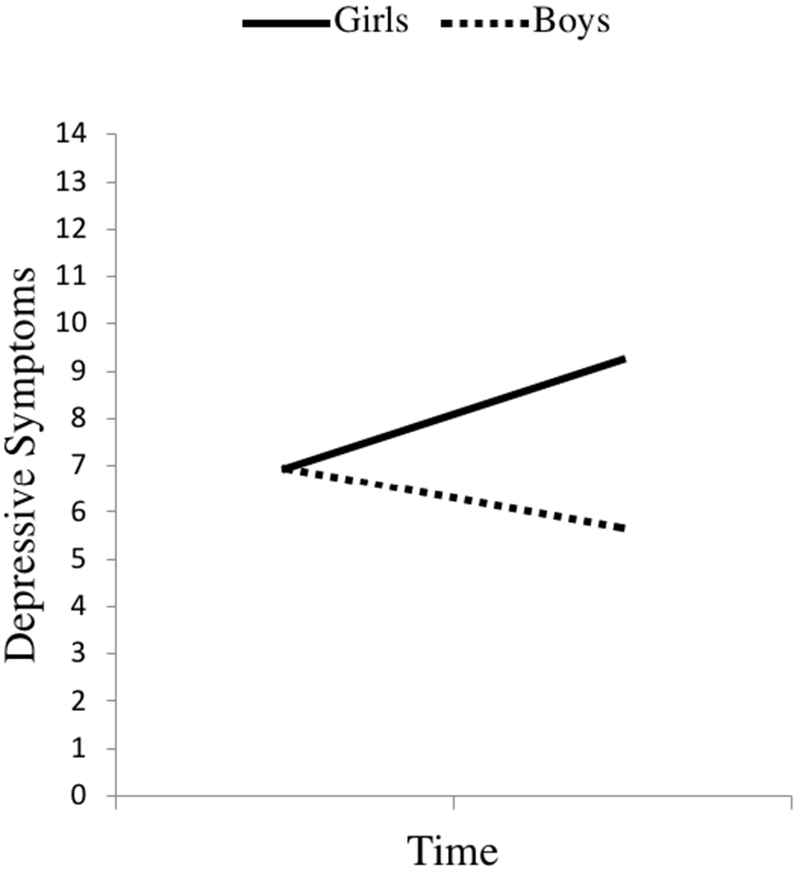

We began by specifying an unconditional means model, which allowed us to examine the proportion of variance attributed to within-adolescent versus between-adolescent variance in depressive symptoms. This model was constructed as a two-level model with three depression time points nested within each adolescent, revealing that 58% of the total variance (σ2u = 29.48) in depressive symptoms was attributed to differences between adolescents, whereas 42% of the total variance was attributed to within adolescent differences (σ2e = 21.60). Higher between subject variance indicates that a larger portion of variability may be due to changes in developmental factors (e.g., emotion, age, gender) rather than intra-personality variability across time. Next, we tested an unconditional linear growth model to examine the rate of change in depressive symptoms (with no additional predictors in the model). Results of the unconditional linear growth model indicated that the linear effect of time on depressive symptoms was not statistically significant (B = 0.22, SE = 0.24, p > .10), suggesting that adolescent depressive symptom scores did not significantly change over time. However, preliminary examination of mean scores (Table 3) for adolescent depressive symptoms suggested that girls’ depressive symptoms increased over time whereas boys’ depressive symptoms decreased over time. Since mean scores suggested that boys and girls have opposing rates of change in depressive symptoms, the overall effect of time on depression may be canceled out when both genders were included in the model. Thus to follow up, we tested a growth model including gender as a level 2 predictor of change in depressive symptoms, and as anticipated, found that the linear random effect of time was statistically significant when gender was included in the model (B = 1.09, SE = 0.28, p < .001), with gender also representing a significant effect (B = −1.66, SE = 0.29, p < .001). Specifically, girls’ depressive symptoms increased over time, whereas boys’ depressive symptoms decreased over time (see Figure 4). In addition, the intercept coefficient for this model was 6.95 (SE = 0.45, p < .001), reflecting the average depressive symptom score for both boys and girls at Time 1.

Figure 4.

Trajectory of depressive symptoms for boys and girls.

We then conducted a conditional growth model including adolescent ER difficulties, to test our hypothesis that overall ER difficulties at Time 1 will predict increased depressive symptoms across time. Specifically, we created a conditional growth model, in which Time 1 ER difficulties, gender, and Time 1 ER difficulties X gender interaction were entered as Level 2 predictors of the depressive symptom slope. Results showed a significant linear effect of Time 1 ER difficulties (B = .03, SE = .01, p < .01) on change in depressive symptoms, such that higher levels of ER difficulties at Time 1 were associated with greater increases in depressive symptoms over time. To better understand the size of this effect, we examined the standardized beta coefficient for this analysis. It revealed that for every one standard deviation increase in ER difficulties, depressive symptoms increased by .10 standard deviations. Gender remained a significant predictor (B = −1.87, SE = .41, p < .001), with girls showing greater increases in depressive symptoms over time. However, the gender X ER difficulties interaction was not significant, B = −.03; SE = .02, p = .13.

We then explored the effects of specific ER difficulties at Time 1 on adolescent depressive symptoms in separate conditional growth models by examining each ER difficulty (see Table 5). Following Bonferonni correction, only one of the six ER difficulties at Time 1 (limited access to ER strategies) was related to greater increases in depressive symptoms (B = .13, SE = .04, p = .02). Gender did not moderate any of these relations.

Table 5.

Difficulties in ER Predicting Depressive Symptom Trajectory

| Variable | B | SE | Uncorrected p value | Corrected p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Model | ||||

| Gender | −1.87 | .41 | <.001*** | - |

| Overall DERS | .03 | .01 | .007** | - |

| Overall DERS × Gender | −.03 | .02 | .129 | - |

| Model 1: AWAR | ||||

| AWAR | −.01 | .06 | .90 | 1 |

| AWAR × Gender | −.00 | .08 | .96 | 1 |

| Model 2: EC | ||||

| EC | .19 | .08 | .02 | .10 |

| EC × Gender | −.16 | .13 | .20 | 1 |

| Model 3: NER | ||||

| NER | .07 | .06 | .200 | 1 |

| NER × Gender | −.08 | .09 | .36 | 1 |

| Model 4: IMP | ||||

| IMP | .12 | .06 | .047* | .28 |

| IMP × Gender | .11 | .06 | .05 | .30 |

| Model 5: GDB | ||||

| GDB | .07 | .06 | .20 | 1 |

| GDB × Gender | −.09 | .09 | .29 | 1 |

| Model 6: STRAT | ||||

| STRAT | .13 | .04 | .004* | .02* |

| STRAT × Gender | −.13 | .07 | .08 | .48 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Note. DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, AWAR = Lack of Emotional Awareness, EC = Lack of Emotional Clarity, NER = Nonacceptance of Emotional Responses, IMP = Impulse Control Difficulties, GDB = Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behavior, STRAT = Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine ER difficulties as a predictor of depressive symptoms cross-sectionally in early adolescence and longitudinally from early adolescence to middle adolescence. We also examined gender as a moderator in these relations. We obtained three major findings in this study. First, overall difficulties in ER at Time 1 predicted depressive symptoms cross-sectionally at Time 1 and longitudinally over a two-year period. Second, all six of Gratz and Roemer’s [22] ER difficulties at Time 1 predicted depressive symptoms cross-sectionally. Along with overall ER difficulties, limited access to ER strategies at Time 1 predicted depressive symptoms longitudinally. Third, gender interacted with overall ER difficulties at Time 1 to predict depressive symptoms cross-sectionally (but not longitudinally); that is, overall ER difficulties at Time 1 were more strongly associated concurrently with depressive symptoms for girls than boys. With regard to the specific ER difficulties, gender most strongly moderated the effect of lack of emotional clarity and lack of emotional awareness on current depressive symptoms. These findings and their clinical implications are elaborated below.

ER Difficulties Predict Depressive Symptoms

We postulated that overall ER difficulties at Time 1 would cross-sectionally predict depressive symptoms in early adolescence and prospectively predict depressive symptoms from early to middle adolescence. Our results revealed support for this hypothesis which is consistent with the literature on ER. Young adolescents with a limited ability to regulate their emotions are especially vulnerable to depressive symptoms because they are unable to down-regulate episodes of negative affect and are more likely to have sustained negative affect that can become chronic and pathological, affecting their ability to manage stressors [16, 23]. Our longitudinal finding is an important addition to the literature because it suggests that early impairment in ER up to two years prior can have downstream consequences for middle adolescence.

All of Gratz and Roemer’s [22] ER difficulties at Time 1—lack of emotional awareness, lack of emotion clarity, nonacceptance of emotional responses, impulse control difficulties, difficulties engaging goal directed behavior, and limited access to ER strategies—predicted depressive symptoms cross-sectionally; however, only limited access to ER strategies at Time 1 was a significant predictor longitudinally (along with overall ER difficulties). It is possible that limited access to ER strategies, in comparison to other ER difficulties, leaves an adolescent unable to respond to life stressors effectively. Without access to effective ER strategies, negative affect cannot be down-regulated and may linger and become more chronic [16, 23]. Also, the limited access to ER strategies subscale includes some items that reflect that one cannot access active/effective ER strategies so one just wallows in negative emotions. This may be similar to the concept of rumination, which is one dysfunctional ER approach that has been most specifically linked to depressive symptoms and has been shown to predict increased depressive symptoms over time in adolescence [44]. The other types of ER difficulties that we assessed may not be as impairing as a lack of access to effective strategies in the face of life stressors. For example, an adolescent with a lack of emotional clarity may not be able to distinguish between sadness and anger, but still have the strategies to down-regulate this overall negative affect, reducing the risk of long-term negative affect and depressive symptomology. Furthermore, limited access to ER strategies may reflect poor self-efficacy in handling negative emotion (e.g., one item on the scale was: “When I’m upset, I believe that there is nothing I can do to make myself feel better”). Indeed, reduced emotional efficacy has been related to depressive symptoms [45]. Adolescents that are not confident in their ability to down-regulate negative emotion are more sensitive to life stressors and are more likely to have more frequent episodes of negative affect as a result [46, 47].

Gender Differences

We found that overall ER difficulties at Time 1 are more strongly predictive of depressive symptoms in girls than boys cross-sectionally. This is consistent with our hypothesis that boys would show a weaker relation between difficulties in ER and depressive symptoms. Past research has shown that ER difficulties are more important among girls than boys [48]. There are several explanations for this phenomenon. First, boys may experience less negative life events due to earlier pubertal changes and sexism (e.g., less sexual harassment, body dissatisfaction etc.) that require self-regulation [14]. This means that any difficulties in ER are less likely to lead to major depressive disorder. Second, factors other than ER may be contributing to the development of depressive symptoms among boys. One possibility is blunted reward sensitivity. A study by Morgan and colleagues [38] found that blunted neural activation in response to reward predicted prospective increases in depressive symptoms for boys only. One explanation for this is that blunted neural activation to reward may make it more difficult for boys to experience pleasure in everyday activities (i.e., anhedonia). Thus, it may be the case that boys and girls have different pathways to major depressive disorder, or at least different correlates.

Additional analyses examining each type of ER difficulty separately indicated that lack of emotional clarity and lack of emotional awareness at Time 1 were more associated with more depressive symptoms cross-sectionally for girls than boys. Girls are generally better than boys at appraising their emotional state and this has been shown to be a protective factor against depressive symptoms [18, 49]. However, this may also mean that girls with difficulties in appraising their emotional state may be particularly vulnerable to its effects. It is worth noting that girls scored significantly higher on lack of emotional clarity, but not lack of emotional awareness, than boys (interestingly this is different than the majority of the literature suggesting that boys normally have more of a problem with emotional clarity than girls [37]) and that this may have driven this moderation. Gender did not moderate the cross-sectional relation between any other ER difficulty and depressive symptoms, suggesting that lack of emotional clarity and emotional awareness may be the specific ER difficulties conferring risk for depressive symptoms in girls. Future research should continue to examine these relations in order to determine whether these results can be replicated in other samples of adolescents.

Interestingly, these gender moderations did not replicate longitudinally. Difficulties in ER may be more critical for depressive symptoms in girls than boys in early adolescence and this gender difference may narrow as youth develop into middle adolescence. Early adolescence may be a particularly important time for gender differences because of increases in negative life events in early adolescence for girls (such as sexual harassment) [14, 50, 51] and in hormone-related changes in emotional processing (such as reduced growth of amygdala) [52, 53]. Over time, boys begin to experience more stressors and their own pubertal changes that leave them vulnerable to depressive symptoms in a similar way that girls are.

Clinical Implications

The findings revealed in the current study have significant implications for major depressive disorder prevention efforts. Given that adolescent major depressive disorder transcends the adolescent developmental period and often continues until adulthood, it is best to prevent depressive symptoms beginning in early adolescence [54, 55]. This paper provides evidence for the impact of ER difficulties in early adolescence on future increases in depressive symptoms two years later. Thus, it may be beneficial to foster better ER abilities in adolescents early on, particularly through helping early adolescents gain access to adaptive ER strategies to prevent depressive symptoms. This may enable youth to cope with stressful life events. Further, these findings elucidate the importance of tailoring intervention efforts for each person. For example, ER difficulties may be of greater concern to adolescent girls than adolescent boys during early adolescence and thus girls may especially benefit from interventions focused on improving ER.

Limitations and Future Directions

While this study had many strengths, there are several limitations that should be addressed in subsequent studies. First, we utilized all self-report measures. Although a large body of literature indicates that adolescents are the best reporters of their internalizing symptoms [56], it is still important to have behavioral measures and/or multi-informant reports of ER and depressive symptoms. This is particularly important from a prevention framework, given that parents and other adults (i.e., teachers) are in the position to refer adolescents for evaluation and treatment. Second, we examined these relations in a community sample of adolescents. Although this allows our results to be generalizable to many adolescents, it does not extend to adolescents at greater risk for major depressive disorder. Thus, it is important to consider the impact of ER on clinical levels of major depressive disorder in studies of at-risk adolescents (i.e., family history of major depressive disorder) in subsequent studies. Third, we examined gender as a binary variable, and thus were unable to fully represent in analyses the gender identity of youth who were gender non-binary or transgender. These adolescents may be at an even greater risk for major depressive disorder [7], and it is unclear how their gender identity is related to the development of ER capabilities. Finally, the current analyses did not assess how concurrent changes in ER over time affects depressive symptoms over time. This is important because depressive symptom trajectory may be changed depending on the development of ER. Future studies should examine these bidirectional relations.

Despite these limits, the present study was one of the first to establish a longitudinal link between ER difficulties in early adolescence and future increases in depressive symptoms from early to middle adolescence, a period of risk. Further, our findings suggest that this prospective association was strongest for ER difficulties related to a lack of access to effective ER strategies, suggesting an important role for ER strategy acquisition in prevention efforts. Finally, our results suggest that ER difficulties may be associated cross-sectionally with depressive symptoms more for girls than boys, suggesting gender-sensitive identification of and intervention with at-risk youth.

Summary

The purpose of this study was to examine ER difficulties as a predictor of depressive symptoms cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Results revealed that overall ER difficulties at Time 1 predicted depressive symptoms cross-sectionally during early adolescence and over two years from early to middle adolescence. Gender moderated this relation cross-sectionally only, such that overall ER difficulties at Time 1 predicted depressive symptoms more strongly in girls than boys. In regards to specific ER difficulties, all six ER difficulties at Time 1 (i.e., lack of emotional awareness, lack of emotional clarity, nonacceptance of emotional responses, impulse control difficulties, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, limited access to ER strategies) predicted depressive symptoms during early adolescence, and limited access to ER strategies at Time 1 also predicted changes in depressive symptoms from early to middle adolescence. Additionally, gender moderated the cross-sectional relation between lack of emotional awareness and lack of emotional clarity and depressive symptoms, such that lack of emotional awareness and lack of emotional clarity at Time 1 were more strongly associated with depressive symptoms at Time 1 in girls than boys. These findings suggest that overall ER difficulties and lack of access to ER strategies in early adolescence can have downstream consequences for depressive symptoms two years later. Thus, it may be beneficial to target ER difficulties early, prior to the escalation of depressive symptoms. It may also be helpful to target girls in particular as their ER difficulties, specifically lack of emotional awareness and emotional clarity, are more strongly associated with depressive symptoms in early adolescence.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including R01-DA033431 (PI: Chaplin) and F31-DA041790 (PI: Turpyn).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Avenevoli S, Swendsen J, He JP, Burstein M, Merikangas KR (2015) Major Depression in the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement: Prevalence, Correlates, and Treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaffer D (1996) Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53:339–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohde P, Noell J, Ochs L, Seeley JR (2001) Depression, suicidal ideation and STD-related risk in homeless older adolescents. J Adolesc 24:447–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deykin EY, Levy JC, Wells V (1987) Adolescent depression, alcohol and drug abuse. Am J Public Health 77:178–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glied S, Pine DS (2002) Consequences and correlates of adolescent depression. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 156:1009–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehrer JA, Shrier LA, Gortmaker S, Buka S (2006) Depressive symptoms as a longitudinal predictor of sexual risk behaviors among US middle and high school students. Pediatrics 118:189–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2008) Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49:1270–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen P, Cohen J, Kasen S, Velez CN, Hartmark C, Johnson J et al. (1993) An epidemiological study of disorders in late childhood and adolescence—I. Age-and gender-specific prevalence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 34:851–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Twenge JM, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2002) Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort difference on the children’s depression inventory: A meta-analysis. J Abnorm Psychol 111:578–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charbonneau AM, Mezulis AH, Hyde JS (2009) Stress and emotional reactivity as explanations for gender differences in adolescents’ depressive symptoms. J Youth Adolesc 38:1050–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaplin TM, Aldao A (2013) Gender differences in emotion expression in children: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 139:735–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Aldao A (2011) Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Pers Individ Dif 51:704–708 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gross JJ (2001) Emotion regulation in adulthood: timing is everything. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 10:214–219 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH Jr (2001) Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Dev Psychol 37:404–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cole PM, Michel MK, Teti LO (2008) The Development Of Emotion Regulation And Dysregulation: A Clinical Perspective. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 59:73–102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silk JS, Steinberg L, Morris AS (2003) Adolescents emotion regulation in daily life: links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Dev 74:1869–1880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garnefski N, Kraaij V (2006) Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Pers Individ Dif 40:1659–1669 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumann A, van Lier PA, Gratz KL, Koot HM (2009) Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation Difficulties in Adolescents Using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Assessment 17:138–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng X, Keenan K, Hipwell AE, et al. (2009) Longitudinal associations between emotion regulation and depression in preadolescent girls: moderation by the caregiving environment. Dev Psychol 45:798–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poon JA, Turpyn CC, Hansen A, Jacangelo J, Chaplin TM (2015) Adolescent Substance Use & Psychopathology: Interactive Effects of Cortisol Reactivity and Emotion Regulation. Cognit Ther Res 40:368–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Cicchetti D (2009) Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51:706–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gratz KL, Roemer L (2004) Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 26:41–54 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selby EA, Anestis MD, Joiner TE (2008) Understanding the relationship between emotional and behavioral dysregulation: emotional cascades. Behav Res Ther 46:593–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendryx MS, Haviland MG, Shaw DG (1991) Dimensions of alexithymia and their relationships to anxiety and depression. J Pers Assess 56:227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rieffe C, Rooij MD (2012) The longitudinal relationship between emotion awareness and internalising symptoms during late childhood. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 21:349–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stange JP, Alloy LB, Flynn M, Abramson LY (2013) Negative inferential style, emotional clarity, and life stress: integrating vulnerabilities to depression in adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 42:508–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis B, Sheeber L, Hops H, Tildesley E (2000) Adolescent responses to depressive parental behaviors in problem-solving interactions: implications for depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol 28:451–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S (2010) Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 30:217–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gross JJ, John OP (2003) Individual differences in two ER processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 85:348–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith GT, Guller L, Zapolski TC (2013) A comparison of two models of urgency. Clin Psychol Sci 1:266–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Acremont M, Van der Linden M (2007) How is impulsivity related to depression in adolescence? Evidence from a French validation of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. J Adolesc 30:271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hallfors DD, Walle MW, Bauer D, Ford CA, Halpern CT (2005) Which comes first in adolescence—sex and drugs or depression?. Am J Prev Med 29:163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C (2007) Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 116:198–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klimes–Dougan B, Hastings PD, Granger DA, Usher BA, Zahn-Waxler C (2001) Adrenocortical activity in at-risk and normally developing adolescents: individual differences in salivary cortisol basal levels, diurnal variation, and responses to social challenges. Dev Psychopathol 13:695–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ordaz S, Luna B (2012) Sex differences in physiological reactivity to acute psychosocial stress in adolescence. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37:1135–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Jackson B (2001) Mediators of the gender difference in rumination. Psychol Women Q 25:37–47 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakkinen P, Kaltiala-Heino R, Ranta K, Haataja R, Joukamaa M (2007) Psychometric Properties of the 20-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale and Prevalence of Alexithymia in a Finnish Adolescent Population. Psychosomatics 48:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan JK, Olino TM, McMakin DL, Ryan ND, Forbes EE (2013) Neural response to reward as a predictor of increases in depressive symptoms in adolescence. Neurobiol Dis 52:66–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kovacs M (1992) Children’s depression inventory: Manual. Multi-Health Systems [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bang YR, Park JH, Kim SH (2015) Cut-off scores of the children’s depression inventory for screening and rating severity in Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Investig 12:23–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dubois DL, Felner RD, Bartels CL, Silverman MM (1995) Stability of self-reported depressive symptoms in a community sample of children and adolescents. J Clin Child Psychol 24:386–396. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raudenbush SE, Bryk AS, Congdon R (2011) HLM 7.00 for windows. Scientific Software International, Inc., Lincolnwood [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nezlek JB (2011) Multilevel modeling for social and personality psychology. SAGE Publications Ltd [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burwell RA, Shirk SR (2007) Subtypes of rumination in adolescence: associations between brooding, reflection, depressive symptoms, and coping. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 36:56–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muris P (2002) Relationships between self-efficacy and symptoms of anxiety disorders and depression in a normal adolescent sample. Pers Individ Dif 32:337–348 [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Eck M, Nicolson NA, Berkhof J (1998) Effects of stressful daily events on mood states: relationship to global perceived stress. J Pers Soc Psychol 75:1572–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson D, Clark LA, Carey G (1988) Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Abnorm Psychol 97:346–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill AL, Degnan KA, Calkins SD, Keane SP (2006) Profiles of externalizing behavior problems for boys and girls across preschool: the roles of emotion regulation and inattention. Dev Psychol 42:913–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fernandez-Berrocal P, Alcaide R, Extremera N, Pizarro D (2006) The role of emotional intelligence in anxiety and depression among adolescents. Individ Differ Res 4:16–27 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petersen AC, Sarigiani PA, Kennedy RE (1991) Adolescent depression: why more girls?. J Youth Adolesc 20:247–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Usmiani S, Daniluk J (1997) Mothers and their adolescent daughters: relationship between self-esteem, gender role identity, body image. J Youth Adolesc 26:45–62 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dahl RE, Gunnar MR (2009) Heightened stress responsiveness and emotional reactivity during pubertal maturation: implications for psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 21:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Herting MM, Gautam P, Spielberg JM, Kan E, Dahl RE, Sowell ER (2014) The role of testosterone and estradiol in brain volume changes across adolescence: A longitudinal structural MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 35:5633–5645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pine DS, Cohen E, Cohen P, Brook J (1999) Adolescent depressive symptoms as predictors of adult depression: moodiness or mood disorder?. Am J Psychiatry 156:133–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P (1994) Major depression in community adolescents: age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33:809–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hope TL, Adams C, Reynolds L, Powers D, Perez RA, & Kelley ML (1999) Parent vs. self-report: Contributions toward diagnosis of adolescent psychopathology. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 21:349–363 [Google Scholar]