Abstract

Sterane biomarkers preserved in ancient sedimentary rocks hold promise for tracking the diversification and ecological expansion of eukaryotes. The earliest proposed animal biomarkers from demosponges (Demospongiae) are recorded in a sequence around 100Myr long of Neoproterozoic-Cambrian marine sedimentary strata from the Huqf Supergroup, South Oman Salt Basin. This C30 sterane biomarker, informally known as 24-isopropylcholestane (24-ipc), possesses the same carbon skeleton as sterols found in some modern-day demosponges. However, this evidence is controversial because 24-ipc is not exclusive to demosponges since 24-ipc sterols are found in trace amounts in some pelagophyte algae. Here, we report a new fossil sterane biomarker that co-occurs with 24-ipc in a suite of late Neoproterozoic-Cambrian sedimentary rocks and oils, which possesses a rare hydrocarbon skeleton that is uniquely found within extant demosponge taxa. This sterane is informally designated as 26-methylstigmastane (26-mes), reflecting the very unusual methylation at the terminus of the steroid side chain. It is the first animal-specific sterane marker detected in the geological record that can be unambiguously linked to precursor sterols only reported from extant demosponges. These new findings strongly suggest that demosponges, and hence multicellular animals, were prominent in some late Neoproterozoic marine environments at least extending back to the Cryogenian period.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

The transition from unicellular protists to multicellular animals constitutes one of the most intriguing and enigmatic events in the evolutionary history of life, largely due to the absence of unambiguous physical fossils for the earliest fauna. The Neoproterozoic rise of eukaryotes1, including demosponges2, in marine environments can be discerned from lipid biomarker records preserved in ancient sedimentary rocks that have experienced a mild thermal history. Molecular phylogenies commonly show that sponges (Porifera) are the sister group of other animals3 and molecular evidence for Neoproterozoic animal life was first proposed based on the occurrence of unusual C30 demosponge-derived steranes informally known as 24-isopropylcholestane (24-ipc) steranes in sedimentary rocks and oils of that age2,4. These steranes are the hydrocarbon remains of 24-isopropylcholesterols and structurally related sterols5. The record of 24-ipc steranes commences in Cryogenian-aged sediments in South Oman (around 717–635 million years ago (Ma)2,6) and then occurs continuously through the Ediacaran–Cambrian formations of the Huqf Supergroup of the South Oman Salt Basin. Notably, these steroids also occur as covalently bound constituents fixed within the immobile kerogen phase of the same rocks, which is an important confirmation that these are not younger contaminant compounds that migrated into the rocks2.

Demosponges are the only known extant taxon that can bio-synthesize 24-ipc precursors as their major sterols. High relative absolute abundances of 24-ipc steranes have now been reported in many other late Neoproterozoic–early Cambrian rocks and oils2,4,7–9. These 24-ipc occurrences—if interpreted correctly—reflect an early presence of Porifera and provide a conservative minimum time estimate for the origin of animal multicellularity and the sponge body plan. Others have hypothesized that the 24-ipc steranes could be derived from unicellular animal ancestors or have an algal origin10 since the parent sterols have been reported in trace amounts in some extant pelagophyte algae2. The claim that poribacterial sponge symbionts from the candidate phylum Poribacteria can make 24-ipc steroids11 has since been shown to be erroneous due to a genome assembly error12,13.

Currently, two chromatographically resolvable series of ancient C30 steranes are known: 24-n-propylcholestane (24-npc) and 24-ipc. Demosponges are the most plausible Neoproterozoic–Cambrian source of 24-npc as well as 24-ipc because both are produced by extant demosponges2. Foraminifera are another possible source of 24-npc14. Pelagophyte algae probably account for the 24-npc steranes that are found in Devonian and younger marine sediments and their derived oils13. Various recent findings support a pre-Ediacaran origin of animals and sponges, and arguably reinforce the validity of the 24-ipc biomarker record, including: (1) steroid assays and genomic analyses of extant taxa13, which suggest that sponges were the most likely Neoproterozoic source biota for 24-ipc steranes; and (2) nuclear and mitochondrial gene molecular clock studies, which consistently support a pre-Ediacaran origin of animals and Neoproterozoic demosponges15–18. The discovery of other sponge biomarkers to augment the 24-ipc sterane record would greatly strengthen evidence for the presence of animals before the appearance of the Ediacara fauna, since the efficacy of the standalone 24-ipc sterane record for tracking early demosponges has been contested10,12.

Results and discussion

Here, we report the presence of a new C30 sterane designated 26-methylstigmastane (26-mes) in a suite of Neoproterozoic–Cambrian rocks and oils (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 1–3). Furthermore, we attribute this biomarker to demosponges since these are the only known organisms among extant taxa to produce sterols with the same carbon skeleton (Supplementary Information). The abundance of 26-mes sterane biomarkers is of comparable magnitude to 24-ipc and 24-npc (Fig. 1), although the relative proportions of the three main C30 sterane compounds can vary from sample to sample (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Summed C30 steranes are typically 1–4% of the total C27–30 sterane signal in South Oman rocks, although higher contents >5% can also be found. Our analyses confirm the presence of 26-mes along with 24-ipc steranes in the Neoproterozoic–Cambrian rock extracts and kerogen pyrolysates from South Oman reported previously2,8, as well in Ediacaran–Cambrian-sourced oils from Eastern Siberia9 and India7, for which representative samples are shown in Fig. 1 (see also Supplementary Table 3). When 26-mes is detectable in Cryogenian to Cambrian age rocks and oils, it is found alongside both the 24-ipc and 24-npc sterane compounds. These three different sterane series constitute only a small subset of all the structural possibilities for C30 sterane compounds, which are feasible from adding three additional carbons to a cholestane side chain, and they correspond with three of the most commonly occurring sterane skeletons for C30 sterols found in extant demosponges (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). In contrast, 26-mes abundance is typically lower or absent for the small suite of Phanerozoic oils and rocks analysed thus far but can be detected, along with 24-ipc and 24-npc, in some samples but not in the procedural blanks (Supplementary Table 3).

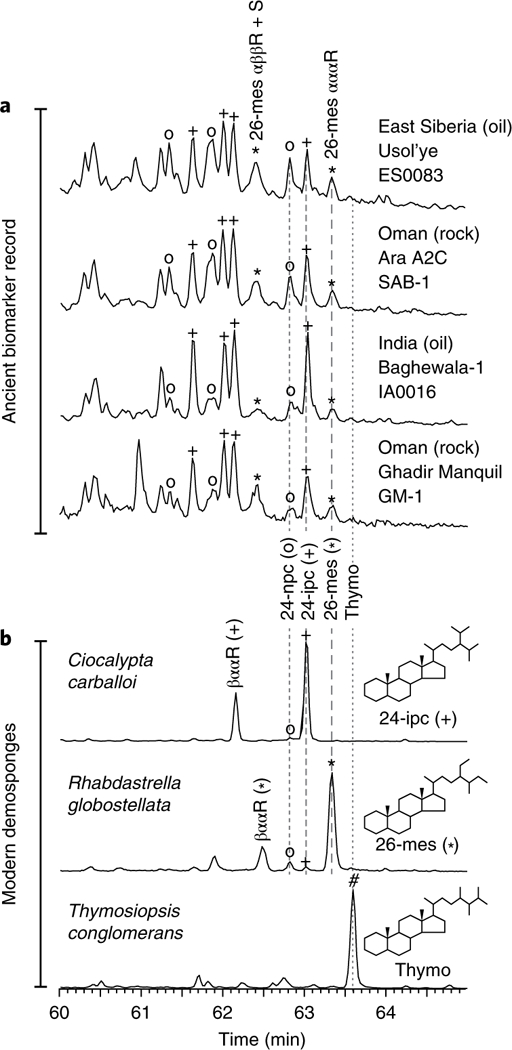

Fig. 1|. MRM-GC-MS ion chromatograms of C30 sterane distributions (414 → 217 Da ion transitions).

a, Results from Neoproterozoic–Cambrian rock bitumens and oils. b, HyPy products from the cells of three modern demosponges (see Supplementary Table 4 for taxonomic assignments). Ancient samples, having undergone protracted burial and alteration, exhibit a more complex distribution of diastereoisomers compared with modern sponge biomass. Four regular sterane diastereoisomers can be found in ancient samples of oil window-maturity (αααS, αββR, αββS and αααR), while two diastereoisomers (βααR and αααR) result from laboratory hydrogenation of individual Δ5-sterols in modern sponge biomass. The signal peak for the αααS geoisomer of 26-mes often co-elutes with other C30 steranes, so this isomer peak is usually obscured in chromatograms. Direct correlation with modern sponges uses the αααR isomer, as shown by the dashed lines. The αββ isomers show expected enhancement of the signal in 414 → 218Da ion chromatograms relative to ααα stereoisomers (not shown here). Examples from the Proterozoic rock record show three distinct resolvable sterane series co-occurring (24-npc, 24-ipc and 26-mes). The rock from Ghadir Manquil Formation, South Oman, was deposited during the Cryogenian period (probably around 660–635 Ma) and is the oldest example in the rock record known with 24-ipc and 26-mes co-occurring. The 26-mes sterane biomarker was detected in significant amounts in the South Oman rock extracts and kerogen pyrolysates reported previously2 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The oil from the Usol’ye Formation, Eastern Siberia, is probably Ediacaran to Early Cambrian in source age9, as is the Baghewala-1 oil from India7. An ‘o’ symbol represents 24-npc, a plus 24-ipc and an asterisk 26-mes. Thymo, thymosiosterane (24,26,26’-trimethylcholestane).

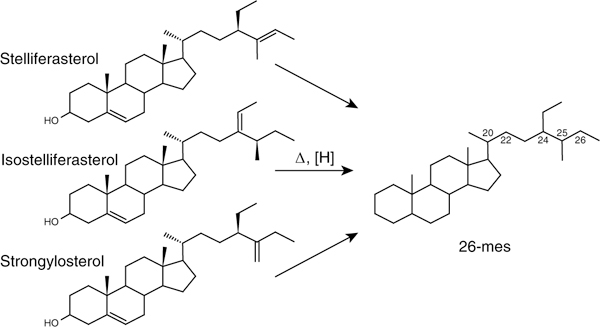

To unequivocally confirm the assignment of the newly identified ancient sterane series as 26-mes, we compared the C30 sterane distributions of Neoproterozoic rocks and oils with sterane products derived from steroids of modern sponges comprising demosponges, hexactinellids, homoscleromorphs and calcisponges (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). We applied catalytic hydropyrolysis (HyPy)—a mild reductive technique employing high-pressure hydrogen—to transform sterols from sponge bio-mass into steranes with minimal structural and stereochemical disturbance19. Only three compatible parent C30 sterols, with an identical side chain skeleton to 26-mes, are currently known in extant taxa (Fig. 2), and these were the probable precursors to the sedimentary 26-mes described above (Supplementary Information). Rhabdastrella globostellata was used as a model sponge species for initial investigations since its sterols have been previously well characterized20,21 and it contains stelliferasterol as the major C30 sterol constituent, which was verified for our specimens (Supplementary Fig. 1). We generated a simple C30 sterane distribution as expected from the HyPy conversion of the R. globostellata sterols, dominated by 26-mes stereoisomers (Supplementary Fig. 2), and these products were used as a sterane standard to unequivocally test for presence or absence of the 26-mes biomarker in modern and ancient samples (Fig. 1). The identification of the fossil 26-mes sterane series was verified by observing co-elution of the 5α,14α,17α(H)-20R stereoisomer with the same isomer produced from R. globostellata and other extant demosponges (Fig. 1). This co-elution was further confirmed using two different gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) techniques in two different laboratories using different gas chromatography column stationary phases (see Methods).

Fig. 2|. Chemical structures of stelliferasterol, isostelliferasterol and strongylosterol.

These are the three known natural sterol precursors of the 26-mes sterane biomarker20,21,23,39,40 They are found only in certain demosponges, but not detected in other groups of eukaryotes. Note:(1) the methyl-substituent at the terminal position of the sterol side chain, which remains preserved at C-26 in 26-mes; and (2) the unusual double bond positions in the side chains of stelliferasterol and strongylosterol. The biological configuration is 20R for all three sterols, 24R for strongylosterol and stelliferasterol, and 25S for isostelliferasterol. Three stereogenic carbon atoms exist in the side chain of 26-mes (chirality at C-20, C-24 and C-25), but only C-20 stereoisomers give separate compound peaks, producing up to four regular stereoisomers of 26-mes (αααS, αββR, αββS and αααR) in ancient rocks and oils, as has also been found for other sterane compounds.

To better constrain the taxonomic distribution of 26-mes, we supplemented literature reports with targeted analyses of extant sponges using HyPy to directly convert sterols into steranes (Supplementary Table 5). Species of Rhabdastrella and Geodia both produced appreciable amounts of 26-mes after the reductive conversion of sterols to steranes via HyPy treatment (1–9% of total C27–30 steranes; Supplementary Table 5). Apart from Geodia hentscheli, which only makes conventional sterols for which side chain alkylation is restricted to the C-24 position, 26-mes was the predominant C30 sterane product in our Rhabdastrella and Geodia specimens. Molecular phylogenetic results indicate that these species are closely related within Geodiidae (order Tetractinellida). Additionally, we also detected trace amounts of 26-mes steranes along with 24-ipc and 24-npc in four species of Aplysina and Verongula (order Verongiida) and one species of Cymbaxinella (order Agelasida) (Supplementary Table 5). No 26-mes precursors were detected in a Jaspis species, where stelliferasterol and isostelliferasterol were supposedly originally discovered20,21. This is consistent with the belief that the original Great Barrier Reef ‘Jaspis stellifera’ specimens were misidentified and were in fact R. globostellata22. Our HyPy results for three specimens of R. globostellata confirmed that 26-mes sterol precursors were present, as well as in two other Rhabdastrella species. Other than the Geodiidae, another known major source of 26-mes steroids is Petrosia (Strongylophora) cf. durissima23 (order Haplosclerida), which can synthesize strongylosterol (Fig. 2) as its dominant single sterol. As not all demosponges make 26-mes, Geodiidae and P. (S.) cf. durissima may have retained the ancestral capacity to make terminally methylated C30 steroids as major membrane lipids, which has been lost in other demosponge groups.

Our new findings of 26-mes production in Geodia, Rhabdastrella, Aplysina (aspiculate), Verongula (aspiculate) and Cymbaxinella species suggest that a wider range of demosponge groups might possibly make 26-mes, as well as other terminally methylated steroids, but have not yet been identified. These demosponge species and others can make various unusual C29 and C30 sterols with terminal methylation in the side chain (Supplementary Information). For example, Thymosiopsis conglomerans (order Chondrillida) makes a distinctive C30 sterol24, yielding a different sterane skeleton that has not been detected in the ancient record (Fig. 1). The finding of this extra terminal carbon atom in a variety of sterols from diverse extant demosponges suggests that the capability for 26-methylated sterol side chains probably has a deep origin within the clade. In the case of both 24-ipc2 and 26-mes, the ability to make these sterols is phylogenetically widespread within demosponges. Notably, the known extant demosponge species that contain 26-mes as the dominant hydrocarbon core of their C30 steroids are different from those that make 24-ipc as major steroids. Specifically, the demosponge family Halichondriidae (Ciocalypta (previously Collocalypta), Halichondria and Epipolasis) and the genus Topsentia make 24-ipc among their most abundant sterols12 while 24-ipc constitutes >99% of sterols in Cymbastela coralliophila (Pseudoaxynissa species in the original publication) from the family Axinellidae5.

From a comprehensive database of steroid assays performed on extant organisms from decades of lipid research, alongside our targeted assays here, 26-mes precursor sterols are found only in certain demosponges20,21,23 but—to our knowledge—have never been reported from any other group of eukaryotes (Supplementary Information). This evidence of absence applies to diverse groups of algae19,25,26, hexactinellid sponges (ref. 27 and this study) calcisponges (refs 2,28 and this study) homoscleromorphs (this study) and unicellular animal outgroups13. Indeed, only steroids possessing conventional side chains (with methyl, ethyl or propyl groups or a hydrogen substituent at C-24) have been reported for other sponge classes, heterotrophic protists and these unicellular animal outgroups13,14,27,28, but not steroids with unconventional side chains of any variety. Thus, the finding of 26-mes, together with the 24-ipc steranes in Neoproterozoic rocks and oils, is most parsimoniously explained by an origin from demosponges living in marine settings.

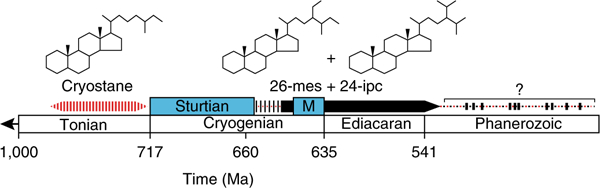

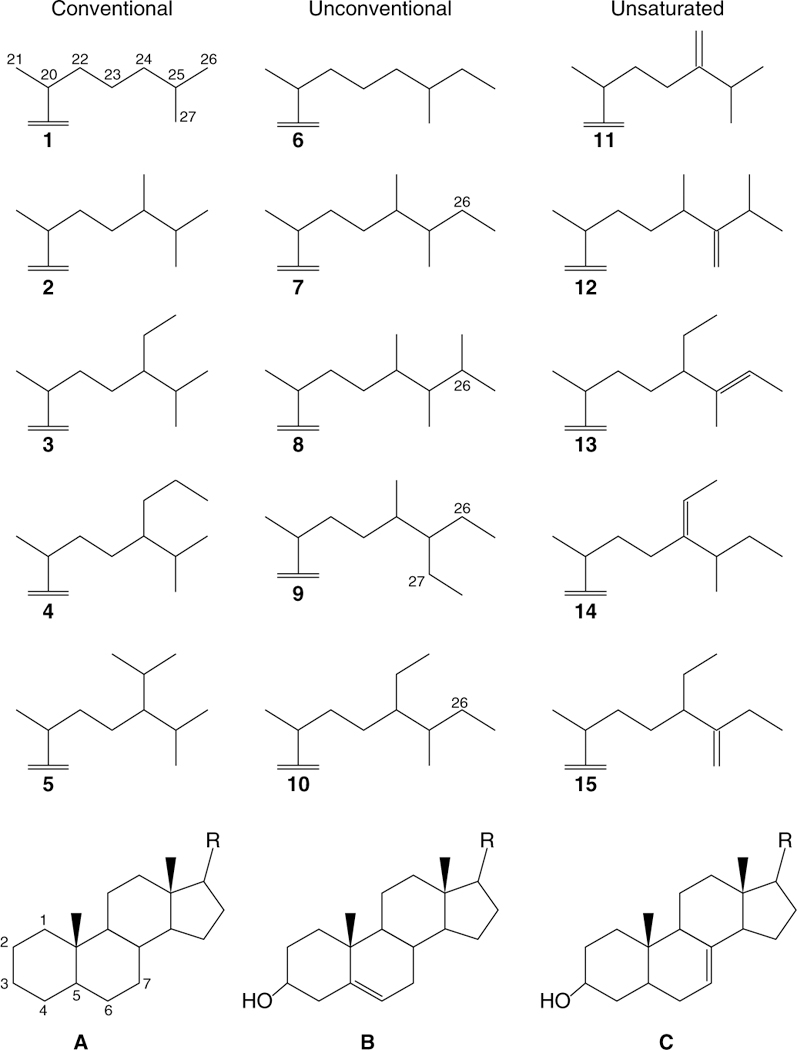

In terms of possible older occurrences of sponge biomarkers, robust evidence for steranes has been reported in some 800–700 Myr Neoproterozoic rocks29,30 from the Chuar Group (USA) and Visingsö Group (Sweden). These rocks contain an unusual C28 sterane, 26-methylcholestane, informally designated as cryostane (Fig. 3), which has been proposed as a possible ancient sponge or unicellular stem metazoan marker29. Cryostane is also characterized by the unusual terminal side chain methylation at C-26, making it a structural analogue of 26-mes and adding credence to the case for cryostane being a plausible ancient sponge biomarker. However, plausible precursor sterols for cryostane have not yet been found in any extant organisms, despite the discovery of a wide variety of other unconventional steroid structures in modern sponges. The Chuar and Visingso Group rocks, like all pre-Sturtian-aged samples reported so far, are devoid of 24-ipc, 24-npc and 26-mes steranes. Thus, cryostane cannot currently be applied as a robust animal biomarker until more is known about its biological origins and whether the biosynthetic capacity to make unconventional 26-methylated steroids (Fig. 4) is restricted to demosponges or otherwise. The origins of cryostane are intriguing and a bridging of the cryostane and 26-mes/24-ipc records may signify a continuity of sponge markers persisting through the two Neoproterozoic glaciation events (Fig. 3), but this requires further investigation.

Fig. 3|. A revised Neoproterozoic-Cambrian timeline showing co-occurrences of 26-mes and 24-ipc sterane biomarkers.

The South Oman record commences in the Cryogenian period (>635 Ma) after the Sturtian glaciation (terminating at around 660 Ma6) and continues throughout the Ediacaran period into the Early Cambrian for Huqf Supergroup rocks (Supplementary Tables 1–2). Other Ediacaran oils also contain the C30 steranes series (Supplementary Table 3), but some Ediacaran rocks are devoid of the C30 sterane series, although they contain predominantly algal steranes with a C29 dominance40. The distribution and abundance patterns of the C30 sterane 26-mes have yet to be fully established for the Phanerozoic rock record; however, it can be detected in some Phanerozoic rocks and oils (see Supplementary Table 3). Cryostane is a potentially older biomarker for sponges or unicellular protists, and it has been detected in pre-Sturtian rocks in the 800–717 Myr age range29 but not in older samples. Cryostane is a C28 sterane analogue of 26-mes, but corresponding sterol precursors for cryostane have never been reported from any extant taxa despite the identification of 26-mes demosponge sterols many decades ago20,21,23,38,39. ‘M’ signifies the Marinoan glaciation; cryostane temporal range is represented by red shading although possible ocurrences in younger rocks and oils require further investigation; 26-mes and 24-ipc range is represented by the black bar.

Fig. 4|. Chemical structures for a selection of conventional, unconventional and unsaturated sterols found in modern eukaryotic taxa.

Chemical structures numbered 1–15 (top) represent possible variations of the part of the structure labelled ‘R’ in structures A-C (bottom). Conventional sterols show side chain alkylation of the C27 cholestane core skeleton restricted to the C-24 position, while all examples of unconventional sterols shown here have extended side chains arising from terminal methylation at C-26 and/or C-27. Note that the tetracyclic core and/or side chain of sterols may or may not contain an alkene bond, and when alkene bonds are present these sterols are known as unsaturated compounds. In this scheme, cholesterol is compound B1, stelliferasterol is B13, isostelliferasterol is B14 and strongylosterol is B15. The dominant ancient fossil form is sterane (A), with alcohol and alkene bonds removed by chemical reduction.

Conclusions

The co-occurrence of 24-ipc and 26-mes steranes constitutes the earliest robust biomarker evidence for Neoproterozoic animals, first detected in the Cryogenian period before the deposition of the Marinoan cap carbonate (>635 Ma), but following the Sturtian glaciation (beginning at <717 Ma and terminating around 660 Ma)2,6. This suggests that demosponges first achieved ecological prominence in Neoproterozoic marine paleoenvironments, at least between 660 and 635 Ma, which is consistent with recent molecular clock predictions for their first appearance15–18. This view from molecular clocks and biomarkers remains to be reconciled with the fossil spicule record, which suggests a later (Cambrian) origin31. Future sampling of modern taxa may reveal other sources of 26-mes steroids (see Supplementary Information), but multiple possibilities for taphonomic mega-bias of early sponge body fossils have been identified (see ref. 32 and the references therein), perhaps related to sparse biomineralization and/or silica dissolution and reprecipitation in low-oxygen marine conditions33, despite overall higher Proterozoic oceanic silica levels. The records could also be reconciled if demosponge spicules evolved convergently in the Cambrian or if aspiculate demosponges were dominant producers of Neoproterozoic 26-mes and 24-ipc.

All available current data indicate that 26-mes steranes are made by diverse species of modern demosponges, and apparently not by any other sponge class (Hexactinellida, Homoscleromorpha or Calcarea) or other extant eukaryote, implying that Neoproterozoic total-group demosponges were the most probable source biota for these biomarkers. As demosponges are derived within Porifera, these data consequently predict the presence of sponges at this time irrespective of whether sponges3 or ctenophores34 are the sister group of all other animals. Thus, this new Neoproterozoic steroid biomarker evidence for demosponges provides a conservative minimum time estimate for the origin of animal multicellularity and the sponge body plan involving feeding with a water canal system.

Methods

Catalytic HyPy of sponge biomass.

Continuous-flow HyPy experiments were performed on 30–150 mg of catalyst-loaded sponge biomass at the University of California, Riverside (UCR) as described previously2,19. Freeze-dried sponge biomass was initially impregnated with an aqueous methanol solution of ammonium dioxydithiomolybdate ((NH4)2MoO2S2) to give a nominal loading of 3–10 wt% catalyst. Ammonium dioxydithiomolybdate reductively decomposes in situ under HyPy conditions above 250 °C to form a catalytically active molybdenum sulfide (MoS2) phase.

The catalyst-loaded samples were heated in a stainless-steel (316 grade) reactor tube from ambient temperature to 250 °C at 100 °C min−1, then to 460 °C at 8 °C min−1. A hydrogen sweep gas flow rate of 6 dm3 min−1, measured at ambient temperature and pressure, through the reactor bed ensured that the residence times of volatiles generated were of the order of only a few seconds. Products were collected on a silica gel trap cooled with dry ice and recovered for subsequent fractionation using silica gel adsorption chromatography.

HyPy products (hydropyrolysates) of sponge biomass were separated by silica gel adsorption chromatography into aliphatic (alkane + alkene), aromatic and polar (or nitrogen, sulfur or oxygen) compounds by elution with n-hexane, n-hexane:dichloromethane (DCM) (1:1 v/v) and DCM:methanol (3:1 v/v), respectively. For hydropyrolysates, solvent-extracted activated copper turnings were added to concentrated solutions of aliphatic hydrocarbon fractions to remove all traces of elemental sulfur, which is formed from disproportionation of the catalyst during HyPy. Aliphatic fractions were further purified to a saturated hydrocarbon fraction by the removal of any unsaturated products (alkenes) via silver nitrate-impregnated silica gel adsorption chromatography and elution with n-hexane.

Lipid biomarker analysis of ancient rocks/oils.

Detailed methods for the extraction and analysis of sedimentary rocks and oils at UCR were described previously35–37 and data are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Rock pieces were first trimmed with a water-cooled rock saw to remove outer weathered surfaces (of at least a few mm thickness) and expose a solid inner portion. They were then sonicated in a sequence of ultrapure water, methanol, DCM and hexane before a final rinse with DCM before powdering and bitumen extraction. Rock fragments were powdered in a zirconia ceramic puck mill in a SPEX 8515 shatterbox,and cleaned between samples by powdering two batches of fired sand (850 °C overnight) and rinsing with the above series of solvents. Typically, 5 g of crushed rock was extracted in a CEM Microwave Accelerated Reaction System at 100 °C in a DCM:methanol (9:1 v/v) mixture for 15 min. Full laboratory procedural blanks with combusted sand were performed in parallel with each batch of rocks to ensure that any background signals were negligible compared with biomarker analyte abundances found in the rocks (typically by at least three orders of magnitude). Saturated hydrocarbon and aromatic fractions for rock bitumens and oils were obtained by silica gel column chromatography; the saturate fractions were eluted with hexane and the aromatic fractions with DCM:hexane (1:1 v/v).

The procedures for ancient biomarker analyses from sedimentary rocks from the Huqf Supergroup of the South Oman Salt Basin performed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (results reported in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2) were similar to those described above for UCR protocols, including multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)-GC-MS methods (see below), which have been described in detail previously2,8. Analytical errors for absolute yields of individual hopanes and steranes are estimated at ±30%. Average uncertainties in hopane and sterane biomarker ratios are ±8%, as calculated from multiple analyses of a saturated hydrocarbon fraction from Australian Geological Survey Organisation (AGSO) and GeoMark Research standard oils (n = 30). Full procedural blanks with combusted sand were run in parallel with each batch of samples to quantify any low background signal. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 contain original data from Love et al.2, but now also with 26-mes sterane data added. The yields and ratios verify that significant abundances of 26-mes were detected in all of these samples at a similar order of magnitude abundance to those of 24-ipc steranes.

Sterane analysis using MRM-GC-MS.

Saturated hydrocarbon fractions from ancient rocks and oils, as wells as from modern sponge HyPy pyrolysates, were analysed by MRM-GC-MS conducted at UCR on a Waters Autospec Premier mass spectrometer equipped with an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph and DB-1MS coated capillary column (60 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm film) using helium as the carrier gas. Typically, 1 μl of a hydrocarbon fraction dissolved in hexane was injected onto the gas chromatography column in splitless injection mode. The gas chromatography temperature programme consisted of an initial hold at 60 °C for 2 min, heating to 150 °C at 10 °C min−1 followed by heating to 320 °C at 3 °C min−1, and a final hold for 22 min. Analyses were performed via splitless injection in electron impact mode, with an ionization energy of 70 eV and an accelerating voltage of 8 kV. MRM transitions for C27–C35 hopanes, C31–C36 methylhopanes, C21–C22 and C26–C30 steranes, C30 methylsteranes and C19–C26 tricyclic terpanes were monitored. Procedural blanks with pre-combusted sand yielded less than 0.1 ng of individual hopane and sterane isomers per gram of combusted sand37. Polycyclic biomarker alkanes (tricyclic terpanes, hopanes, steranes and so on) were quantified by the addition of a deuterated C29 sterane standard (d4-ααα—24-ethylcholestane (20R)) to saturated hydrocarbon fractions and comparison of the relative peak areas. In MRM analyses, this standard compound was detected using 404 → 221 Da ion transition. Cross-talk of the non-sterane signal in 414 → 217 Da ion chromatograms from C30 and C31 hopanes was <0.2% of the 412 → 191 Da hopane signal (mainly 17α,21β(H)-hopane, which is resolvable from C30 steranes) and <1% of the 426 → 191 Da signal, respectively36.

Peak identifications of sponge steranes were confirmed by comparing the retention times with an AGSO oil saturated hydrocarbon standard and Neoproterozoic oils from Eastern Siberia4,9 and India7, which were reported previously to contain significant quantities of 24-ipc and which we have now demonstrated contain significant quantities of 26-mes (Supplementary Table 3). Polycyclic biomarkers were quantified assuming equal-mass spectral response factors between analytes and the d4-C29-ααα−24-ethylcholestane (20R) internal standard. Analytical errors for absolute yields of individual hopanes and steranes are estimated at ±30%. Average uncertainties in hopane and sterane biomarker ratios are ±8%, as calculated from multiple analyses of a saturated hydrocarbon fraction prepared from AGSO and GeoMark Research standard oils (n = 30 MRM analyses).

Sterane analysis by gas chromatography triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (GC-QQQ-MS).

To confirm the presence of the new 26-mes peak and investigate the retention time of the analyte peaks compared with other C30 steranes (24-npc and 24-ipc), the saturated hydrocarbon fractions from sponge HyPy products and oils from Eastern Siberia and India (Supplementary Table 3) were run on a different instrument employing a different gas chromatography column from that used in the MRM-GC-MS instrument at UCR. GC-QQQ-MS was performed at GeoMark Research (Houston, Texas) on an Agilent 7000A Triple Quad interfaced with an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph equipped with a J&W Scientific capillary column (DB-5MS + DG: 60 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness, 10 m guard column). Using helium as the carrier gas, the flow was programmed from 1.2 to 3.2 ml min−1. The gas chromatography oven was programmed from 40 °C (2 min) to 325 °C (25.75 min) at 4 °C min−1. Saturated hydrocarbon fractions were spiked with a mixture of seven internal standards (Chiron Routine Biomarker Internal Standard Cocktail 1). Samples were concentrated without being taken to dryness and were injected in cold splitless mode at 45 °C with the injector temperature ramped at 700 °C min−1 to 300 °C. The mass spectrometry source was operated in electron ionization mode at 300 °C with ionization energy at −70 eV. A number of molecular ion to fragment transitions were monitored throughout the run; the dwell time was adjusted as needed to produce 3.5 cycles s−1. Exact chromatographic co-elution (with identical retention time in the C30 sterane analytical window) of the αααR diastereoisomer of 26-mes sterane in our ancient oils with the equivalent peak from the modern sponges was demonstrated in 414 → 217 Da ion transitions (the parent molecular mass to daughter fragment ion transition for regular (4-desmethyl) C30 sterane compounds).

Extraction and analysis of sterols in modern sponge cells.

A total of 18 modern sponge samples were acquired for solvent extraction to monitor their free sterol contents (as trimethylsilyl ethers). Sponge specimens were supplied by co-authors P.C. and E.A.S. and their colleagues, including J. Vacelet, U. Hentschel, K. Peterson, T. Molinski, T. Pérez, H. Tore Rapp, A. Plotkin, J.-S. Hong, Y. M. Huang, S. Rohde, S. Nichols, B. Calcinai, J. V. Lopez, G. Gatti, B. Ciperling, J.-P. Fonseca, L. Magro, F. Azzini and A. G. Collins, and the Bedford Institute of Oceanography (Dartmouth, Canada). Sponge biomass arrived immersed in ethanol or freeze-dried. Combined ethanol washings for each sample were filtered to remove suspended particulates, concentrated into a small volume and then transferred to a pre-weighed glass vial and blown down carefully under dry N2 gas. Freeze-dried sponge biomass was extracted via sonication for 25 min in DCM:methanol (3:1 v/v) to recover the total lipid extract.

Total lipid extracts were separated into three fractions, based on polarity, by silica gel absorption chromatography. Approximately 1–5 mg of total lipid extract was adsorbed on the top of a 10 cm silica gel pipette column and then sequentially eluted with 1.5 column volumes of n-hexane (fraction 1), 2 column volumes of DCM (fraction 2) and 3 column volumes of DCM:methanol (7:3 v/v) (fraction 3). The alcohol products, including sterols, typically eluted in fraction 2, and approximately 20–50 μg of this fraction was derivatized with 10 μl of bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide in 10 μl of pyridine at 70 °C for 30 min.

Alcohol fractions were then analysed by GC-MS as trimethylsilyl ethers within 36 h of derivatization in full scan mode at UCR using GC-MS on an Agilent 7890A gas chromatography system coupled to an Agilent 5975C inert Mass Selective Detector mass spectrometer. Sample solutions were volatilized via programmed-temperature vaporization injection onto a DB-1MS capillary column (60 m × 0.32 mm, 0.25 μm film thickness) and helium was used as the carrier gas. The oven temperature programme used for gas chromatography for the derivatized alcohol fraction consisted of an initial temperature hold at 60 °C for 2 min, followed by an increase to 150 °C at 20 °C min−1, then a subsequent increase to 325 °C at 2 °C min−1 and a hold for 20 min. Data was analysed using ChemStation G10701CA (Version C) software (Agilent Technologies). C30 sterol identifications for the three 26-mes precursors (stelliferasterol (B13), isostelliferasterol (B14) and strongylosterol (B15); see also Fig. 2) in certain Rhabdastrella and Geodia sponge species were identified from published mass spectral features and relative retention times20,21,23,38,39. Stelliferasterol was the dominant C30 sterol in R. globostellata (PC922; Supplementary Figs. 1–2), while strongylosterol, stelliferasterol and isostelliferasterol were found in Geodia parva (GpII).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding support for this work came from the NASA Astrobiology Institute teams Alternative Earths (NNA15BB03A) and Foundations of Complex Life (NNA13AA90A), NASA Exobiology program (grant number 80NSSC18K1085), NSF Frontiers in Earth System Dynamics programme (grant number 1338810), Agouron Institute, and European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme through the SponGES project (grant agreement number 679849). Many thanks go to the sponge collectors, including T. Pérez, H. Tore Rapp, A. Plotkin, J.-S. Hong, Y. M. Huang, S. Rohde, S. Nichols, J. V. Lopez, B. Calcinai, G. Gatti, B. Ciperling, J. Boavida, J.-P. Fonseca, L. Magro and F. Azzini. The fieldwork on the Mohns and Knipovich Ridges aboard the RV G. O. Sars in 2014 was supported by the Research Council of Norway through the Centre for Geobiology, UiB (contract number 179560). A Vazella pourtalesii specimen was provided by E. Kenchington through funding from the Marine Conservation Target fund of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Other specimens were provided by E. Kenchington as Canadian lead for the NEREIDA (NAFO Potential Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems-Impacts of Deep-sea Fisheries) project led by Spain and Canada. We thank K. Ubhayasekera (Department of Chemistry, Uppsala University) for GC-MS analyses, and S. Rajendran and T. Aljazar (Department of Medicinal Chemistry, Uppsala University) for help with the isolation of sponge sterols. We thank Petroleum Development Oman for Neoproterozoic–Cambrian rock samples from the South Oman Salt Basin for ancient biomarker analysis. We are grateful to D. Rocher for GC-QQQ-MS analysis and GeoMark Research (Houston, TX) for providing oil samples from Eastern Siberia.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0676-2.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brocks JJ et al. The rise of algae in Cryogenian oceans and the emergence of animals. Nature 548, 578–581 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Love GD et al. Fossil steroids record the appearance of Demospongiae during the Cryogenian period. Nature 457, 718–721 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simion P et al. Large and consistent phylogenomic dataset supports sponges as the sister group to all other animals. Curr. Biol. 27, 958–968 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCaffrey MA et al. Paleoenvironmental implications of novel C30 steranes in Precambrian to Cenozoic age petroleum and bitumen. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 529–532 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofheinz W & Oesterhelt G 24-isopropylcholesterol and 22-dehydro-24-isopropylcholesterol, novel sterols from a sponge. Helv. Chim. Acta 62, 1307–1309 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rooney AD, Strauss JV, Brandon AD & Macdonald FA A Cryogenian chronology: two long-lasting synchronous Neoproterozoic glaciations. Geology 43, 459–462 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters KE et al. Recognition of an Infracambrian source rock based on biomarkers in the Baghewala-1 oil, India. AAPG Bull. 79, 1481–1494 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grosjean E et al. Origin of petroleum in the Neoproterozoic–Cambrian South Oman Salt Basin. Org. Geochem. 40, 87–110 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly AE, Love GD, Zumberge JE & Summons RE Hydrocarbon biomarkers of Neoproterozoic to Lower Cambrian oils from Eastern Siberia. Org. Geochem. 42, 640–654 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antcliffe JB Questioning the evidence of organic compounds called sponge biomarkers. Palaeontology 56, 917–925 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegl A et al. Single-cell genomics reveals the lifestyle of Poribacteria, a candidate phylum symbiotically associated with marine sponges. ISME J. 5, 61–70 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Love GD & Summons RE The record of Cryogenian sponges. A response to Antcliffe. Palaeontology 58, 1131–1136 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold DA et al. Sterol and genomic analyses validate the sponge biomarker hypothesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2684–2689 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grabenstatter J et al. Identification of 24-n-proplidenecholesterol in a member of the Foraminefera. Org. Geochem. 63, 145–151 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erwin DH et al. The Cambrian conundrum: early divergence and later ecological success in the early history of animals. Science 334, 1091–1097 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.dos Reis M et al. Uncertainty in the timing of origin of animals and the limits of precision in molecular timescales. Curr. Biol. 25, 2939–2950 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dohrmann M & Worheide G Dating early animal evolution using phylogenomic data. Sci. Rep. 7, 3599 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuster A et al. Divergence times in demosponges (Porifera): first insights from new mitogenomes and the inclusion of fossils in a birth-death clock model. BMC Evol. Biol. 18, 114 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Love GD et al. An optimised catalytic hydropyrolysis method for the rapid screening of microbial cultures for lipid biomarkers. Org. Geochem. 36, 63–82 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Theobald N & Djerassi C Determination of the absolute configuration of stelliferasterol and strongylosterol—two marine sterols with ‘extended’ side chains. Tetrahedron Lett. 45, 4369–4372 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theobald N, Wells RJ & Djerassi C Minor and trace sterols in marine invertebrates. 8. Isolation, structure elucidation, and partial synthesis of two novel sterols—stelliferasterol and isostelliferasterol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100, 7677–7684 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy JA Resolving the ‘Jaspis stellifera’ complex. Mem. Queensl. Mus. 45, 453–476 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bortolloto M, Braekman JC, Daloze D & Tursch D Chemical studies of marine invertebrates. XXXXVI. Strongylosterol, a novel C-30 sterol from the sponge Strongylophora durissima Dendy. Bull. Soc. Chim. Belg. 87, 539–543 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vacelet J et al. Morphological, chemical and biochemical characterization of a new species of sponge without skeleton (Porifera, Demospongiae) from the Mediterranean Sea. Zoosytema 22, 313–326 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volkman JK Sterols in microorganisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 60, 495–506 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kodner RB, Pearson A, Summons RE & Knoll AH Sterols in red and green algae: quantification, phylogeny, and relevance for the interpretation of geologic steranes. Geobiology 6, 411–420 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blumenberg M, Thiel V, Pape T & Michaelis W The steroids of hexactinellid sponges. Naturwissenschaften 89, 415–419 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagemann A, Voigt O, Wörheide G & Thiel V The sterols of calcareous sponges (Calcarea, Porifera). Chem. Phys. Lipids 156, 26–32 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brocks JJ et al. Early sponges and toxic protists: possible sources of cryostane, an age diagnostic biomarker antedating Sturtian Snowball Earth. Geobiology 14, 129–149 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adam P, Schaeffer P & Brocks JJ Synthesis of 26-methylcholestane and identification of cryostane in mid-Neoproterozoic sediments. Org. Geochem. 115, 246–249 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Botting JP & Muir LA Early sponge evolution: a review and phylogenetic framework. Palaeoworld 27, 1–29 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muscente AD, Marc Michel F., Dale JG & Xiao S Assessing the veracity of Precambrian ‘sponge’ fossils using in situ nanoscale analytical techniques. Precam. Res. 263, 142–156 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berelson WM et al. Anaerobic diagenesis of silica and carbon in continental margin sediments: discrete zones of TCO2 production. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 4611–4629 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whelan NV et al. Ctenophore relationships and their placement as the sister group to all other animals. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1737–1746 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohrssen M, Love GD, Fischer W, Finnegan S & Fike DA Lipid biomarkers record fundamental changes in the microbial community structure of tropical seas during the Late Ordovician Hirnantian glaciation. Geology 41, 127–130 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohrssen M, Gill BC & Love GD Scarcity of the C30 sterane biomarker, 24-n-propylcholestane, in Lower Paleozoic marine paleoenvironments. Org. Geochem. 80, 1–7 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haddad EE et al. Lipid biomarker stratigraphic records through the Late Devonian Frasnian/Famennian boundary: comparison of high-and low-latitude epicontinental marine settings. Org. Geochem. 98, 38–53 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stoilov IL, Thompson JE, Cho JH & Djerassi C Biosynthetic studies of marine lipids. 9. Stereochemical aspects and hydrogen migrations in the biosynthesis of the triply alkylated side chain of the sponge sterol strongylosterol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 108, 8235–8241 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cho JH, Thompson JE, Stoilov IL & Djerassi C Biosynthetic studies of marine lipids. 14. 24(28)-dehydroaplysterol and other sponge sterols from Jaspis stellifera. J. Org. Chem. 53, 3466–3469 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pehr K et al. Ediacara biota thrived in oligotrophic and bacterially dominated marine environments across Baltica. Nat. Commun. 9, 1807 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.