Abstract

We have shown that calcium (Ca2+) oscillations in human pulmonary fibroblasts (HPFs) contribute to profibrotic effects of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and that disruption of these oscillations blunts features of pulmonary fibrosis. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) exerts antifibrotic effects in the lung, but the mechanisms for this action are not well defined. We thus sought to explore interactions between PGE2 and the profibrotic agent TGF-β in pulmonary fibroblasts (PFs) isolated from patients with or without idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). PGE2 inhibited TGF-β-promoted [Ca2+] oscillations and prevented the activation of Akt and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-II (CaMK-II) but did not prevent activation of Smad-2 or ERK. PGE2 also eliminated TGF-β-stimulated expression of collagen A1, fibronectin, and α-smooth muscle actin and reduced stress fiber formation in the HPFs. RNA sequencing revealed that HPFs preferentially express EP2 receptors relative to other prostanoid receptor subtypes: EP2 expression is ~10-fold higher than that of EP4 receptors; EP1 and EP3 receptors are barely detectable; and EP2-receptor expression is ~3.5-fold lower in PFs from IPF patients than in normal HPFs. The inhibitory effects of PGE2 on synthetic function and stress fiber formation were blocked by selective EP2 or EP4 antagonists and mimicked by selective EP2 or EP4 agonists, the phosphodiesterase inhibitor isobutylmethylxanthine and forskolin, all of which elevate cellular cAMP concentrations. We conclude that PGE2, likely predominantly via EP2 receptors, interferes with Ca2+ signaling, CaMK-II activation, and Akt activation in IPF-HPFs and HPFs treated with TGF-β. Moreover, a decreased expression of EP2 receptors in pulmonary fibroblasts from IPF patients may contribute to the pathophysiology of this disease.

Keywords: Ca2+ signaling, extracellular matrix gene, fibrosis, prostanoid receptor, PGE2, prostaglandin E2

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary fibrosis is characterized by extensive remodeling of the lung and accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) in the alveolar and interstitial spaces, thereby compromising gas exchange (8). Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) patients have been treated with N-acetylcysteine, corticosteroids and/or cytotoxic agents, all of which are associated with side effects and morbidity. More recently, IPF patients have been treated with pirfenidone or nintedanib, but even these drugs are not ideally effective, in that the disease remains progressive and irreversible (15, 24, 27). IPF annually claims the lives of 40,000 Americans (https://www.pulmonaryfibrosis.org/life-with-pf/about-pf 4) and 5,000 Canadians (1, 25) by robbing them of the ability to breathe, usually within 3–5 years after diagnosis.

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) plays a key role in pulmonary fibrosis (15). Many of the signaling components and pathways by which it exerts its profibrotic effects have been well characterized, including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, ERK/p38 MAPK (31) and various Smad-proteins (2). We have shown that TGF-β also provokes recurring oscillations in cytosolic levels of calcium ([Ca2+]i), which then modulate expression of ECM genes in a frequency-dependent manner (20). Our further investigations revealed that [Ca2+] oscillations alone, i.e., in the absence of added growth factors, were sufficient to increase ECM protein expression in cultured human pulmonary fibroblasts (HPFs) (21) and that pharmacological disruption of the [Ca2+] oscillations suppressed fibrotic changes induced by bleomycin in a murine model of pulmonary fibrosis (18) and by TGF-β or PDGF in cultured HPFs (19, 20). We also found that the [Ca2+] oscillation frequency-dependent action of TGF-β was exerted through activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-II (CaMK-II) but not by PI3K/Akt, ERK/p38, or Smad-protein signaling (21).

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) suppresses a wide variety of profibrotic effects in HPFs, including migration, proliferation, collagen deposition, and differentiation to a myofibroblastic phenotype (5, 23, 29). It has been reported that HPFs synthesize prostanoids, including PGE2, in response to proinflammatory stimuli (12). However, the mechanism(s) for such an autocrine regulation of PFs by PGE2 is/are as yet unclear.

PGE2 acts via G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs): EP receptors, of which there are four isoforms (EP1– EP4). EP1 receptors couple via the heterotrimeric G protein Gq to phospholipase C, thereby generating the second messengers diacylglycerol (which activates protein kinase C) and inositol trisphosphate (which releases internally sequestered Ca2+) (6). EP2, EP3, and EP4 receptors, on the other hand, couple to G proteins that regulate activity of adenylyl cyclase (AC), which produces cAMP: EP2 and EP4 act via the Gs protein to stimulate AC, while EP3 activates the Gi-protein to inhibit AC (6).

Here, we sought to explore mechanisms for the suppression of TGF-β-stimulated prosecretory effects on HPFs by PGE2. We found that PGE2 acts via EP2 and EP4 receptors and increased production of cAMP to disrupt TGF-β-promoted [Ca2+] oscillation signaling. Our results further indicate that this PGE2/cAMP signaling pathway interferes with the same profibrotic pathway that is activated in HPFs of IPF patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

TGF-β was obtained from PeproTech; a 400 nM stock solution was prepared by dissolving TGF-β in 4 mM HCl-0.1% BSA solution. Oregon Green Ca2+ dye, RPMI medium, and Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). PGE2, SC-19220, and CAY10598 were obtained from Cayman Chemicals (Cedarlane Laboratories), and stock solution was prepared by dissolving in EtOH (PGE2) or DMSO (SC-19220). AH13205 and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical. Forskolin, GW 627368, and PF-04418948 were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Cedarlane Laboratories) and stock solution was prepared by dissolving in DMSO. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical. All pharmacological blockers were prepared as 10-mM stock solutions, either as aqueous solutions or in absolute EtOH or DMSO. Aliquots were then diluted with HBSS to obtain the desired final concentration.

Isolation and culture of fibroblasts.

All experimental procedures were approved by the St Joseph’s Hospital Board of Ethics. Lung specimens were obtained, following written informed consent, from donors undergoing lobar excision for carcinoma (3 men and 3 women aged 60–80 yr; 3 were smokers, 1 ex-smoker, and 2 nonsmokers), and sections were harvested from macroscopically normal portions of those tissues. Likewise, following informed consent, lung specimens were obtained from patients undergoing biopsy for unclear interstitial lung disease (3 men and 2 women, aged 60–80 yr: 2 smokers, 1 ex-smoker, no smoking history available for the other 2 patients; 2 of the patients had familial IPF) at the time of lung biopsy. Biopsies revealed a usual interstitial pneumonia pattern on histopathology. Diagnoses of carcinoma or of IPF were made by respirologists and pathologists consulting together at our institution. HPFs were grown from these specimens as described previously (19, 20, 21). Briefly, lung specimens were minced into pieces <2 mm and then grown in 35-mm tissue culture dishes in explant medium (RPMI +20% FBS + antibiotics) at 37°C in 95% air-5% CO2. After 2–3 wk, outgrowing cells were trypsinized and subcultured in 75-cm2 culture flask for further growth. These cells, designated passage 1, were cultivated in growth medium (RPMI + 10% FBS + antibiotics) at 37°C in 95%-5% CO; the culture medium was changed three times per week. Cells for confocal microscopy were cultured in glass bottom Petri dishes in the same growth medium. Experiments were conducted with cells between passages 3 and 10. Cells (24 h serum starved) were pretreated with various pharmacological agents (as indicated) when they were 80–85% confluent.

Confocal fluorimetry of [Ca2+] oscillations.

Cells were loaded with Oregon Green (5 μM) for 40 min at 37°C and then placed in a Plexiglass recording chamber and perfused with HBSS for 30 min to allow for complete hydrolysis of the dye. Confocal microscopy was then performed at room temperature (21–23°C) using a custom-built apparatus described previously (20). The recording rate was generally 1 frame/1.5 s. Inhibitors were delivered via the bathing solution. Picture frames were stored in TIF stacks of several hundred frames on a hard drive using image acquisition software (Video Savant 4.0; IO Industries, London, ON, Canada). Image files were analyzed using ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) as described previously (21).

Protein isolation and Western blot.

The cultured HPFs were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), which contained 20 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail. The lysates were collected after a brief sonication and then centrifuged at 4°C and 14,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and frozen at −80°C until use. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay. Proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk and probed with a 1:1,000 dilution of primary antibody overnight. The following primary antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology: p-Smad, Smad, p-Akt, Akt, p-ERK, ERK, p-CaMK-II, GAPDH, and α-tubulin. α-Smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) antibody was purchased from AbCam (Toronto, ON, Canada). CaMK-II antibody was obtained from Millipore (Etobicoke, ON, Canada). The protein bands were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology) and Western blot detection reagent (GE Healthcare). GAPDH and α-tubulin were used as loading control. Specificity of the antibodies was verified from prior published studies: p-SMAD 2 and SMAD 2 (16, 33), p-Akt and Akt (34), ERK (17), and P-ERK (10). The bands were digitized, subjected to densitometric scanning using ImageJ, and normalized against the loading control.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from the cultured fibroblasts with 1 ml TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. Total RNA concentration and integrity were determined with a microgel bioanalyzer (Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100; Agilent, Mississauga, ON, Canada). RNA (1 μg) was treated with DNAse and reverse transcribed using qScript cDNA SuperMix (Quanta Bioscience, Gaithersburg, MD). The cDNA was amplified by quantitative real-time PCR using the Taqman method with the ABI Prism 7500 PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RT-PCR probe and primer sets in gene expression assays were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Results were normalized to expression of β2-microglobulin. Relative gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCT method (Applied Biosystems).

RNA sequencing.

Total RNA was isolated from the cultured fibroblasts with 0.7 ml of RLT Buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) from the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol and dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. Total RNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop 2000c (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Total RNA (~400 ng) from each sample underwent library preparation and RNA sequencing by the Institute for Genomic Medicine, UC San Diego (La Jolla, CA) core facility. The RNA quality and quantity were assessed with the Agilent RNA ScreenTape assay (Agilent 2200 TapeStation, Agilent, La Jolla, CA). Libraries were prepared using the Illumina Truseq stranded mRNA kit, with libraries sequenced on a Hiseq 4000, with >25 million 75-base pair single reads per sample. FASTQ files were checked for sequencing quality via FASTQC. Transcript expression was quantified using Kallisto v0.43.1 (4) with mean fragment length = 190 and standard deviation of fragment length = 20, using the human Ensembl release 79 reference transcriptome. Gene-level quantifications of estimated counts were obtained using tximport (28); these gene-level counts were used as input in edgeR (26) for differential expression analysis and generation of MDS plots and heatmaps. Normalized gene expression in transcripts per million (generated via Kallisto-tximport) and counts per million (generated via Kallisto-tximport-edgeR) data are available at accession no. GSE119007.

Immunofluorescence.

Immunofluorescence staining for α-SMA was performed on fixed HPFs. Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% PFA and permeabilized with PBS-Triton (0.1%, 5 min). After blocking nonspecific sites with BSA (5%, 30 min), we incubated cells overnight with primary antibody diluted in 5% BSA in a humidified chamber at 4°C. Conjugated secondary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:2,000. Slides were mounted in ProLong-gold with DAPI (ProLong Gold antifade regent with DAPI, Life Technologies). Pictures were taken with an epifluorescence microscope (Olympus IX81) at the same setting (×20 zoom) and exposure time for all pictures.

Data analysis.

Data are reported as means ± SE; n refers to the number of cells studied, taken from more than three independent batches of cells (donors). Statistical comparisons were made using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA, as appropriate; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effects of PGE2 on expression of ECM genes and α-SMA protein in HPFs.

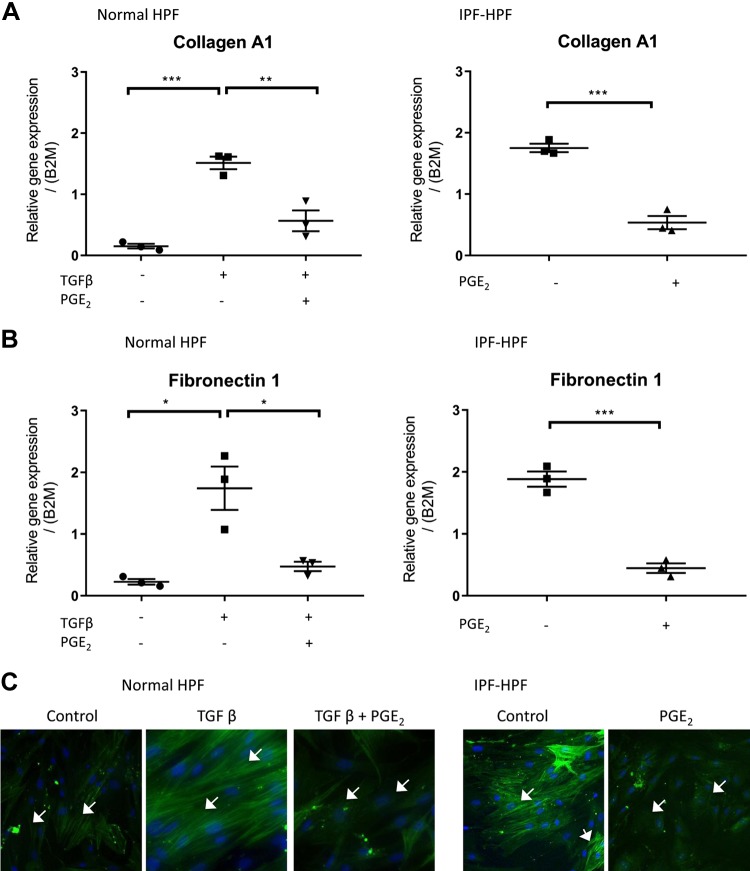

In normal (nondiseased) HPFs, overnight treatment with TGF-β (1 nM) increased the expression of the ECM genes collagen A1 and fibronectin 1 (Fig. 1, A and B). Those responses were substantially reduced if the HPFs were treated with 500 nM PGE2 30 min before TGF-β. Treatment with PGE2 alone had no significant effect on basal expression of collagen A1 or fibronectin 1 in the normal HPFs (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

PGE2 inhibits synthetic function of human pulmonary fibroblasts (HPFs). A–C: expression of collagen A1 (A), fibronectin (B), or α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; C) in the presence/absence of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β; 1 nM) and/or PGE2 (500 nM; added 30 min before TGF-β), as indicated. In each case, panels on the left pertain to normal-HPFs, whereas those on the right pertain to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)-HPFs. Scatterplots indicate mean ± SE values of relative gene expressions; n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005. White arrows (C) indicate α-SMA filaments and blue stain (DAPI) indicate nucleus. Immunofluorescence data (C) shown are representative of at least 4 independent experiments using different cell culture wells (each well contained cells derived from a different unique donor). Photomicrographs were all taken at the same setting (×20 zoom) and exposure time.

In HPFs from patients with IPF, basal levels of collagen A1 and fibronectin 1 expression were more than sixfold greater than in normal unstimulated HPFs and were reduced by PGE2 to levels similar to those in normal HPFs treated with PGE2 (Fig. 1, A and B, right). We did not compare the effect of adding TGF-β to these cells, as IPF cells already exhibit markedly elevated levels of TGF-β production (9); furthermore, we have seen that the persistent [Ca2+] oscillations seen in IPF-HPFs are abolished by treatment with the TGF-β-receptor kinase inhibitor SD-208 (data not shown).

A fluorescent antibody against α-SMA revealed a prominent increase in actin stress fibers in the TGF-β-stimulated (1 nM, 48 h) normal HPFs and a substantial presence of stress fibers in unstimulated IPF HPFs (Fig. 1C): PGE2 treatment reduced stress fiber expression in both cases.

Effects of PGE2 on TGF-β-mediated signal transduction pathways.

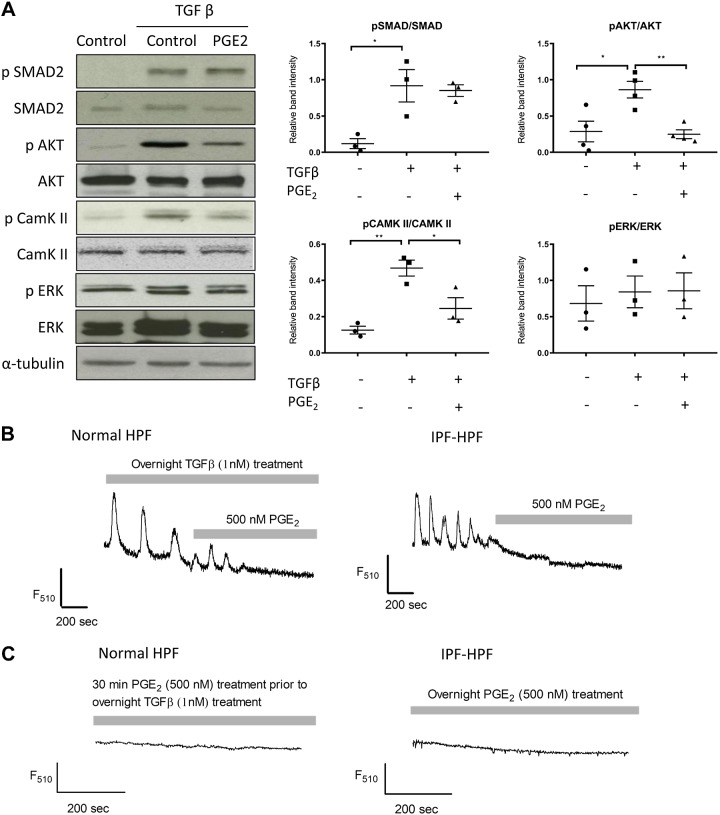

TGF-β mediates its profibrotic effects in part through phosphorylation of SMAD-2, Akt, and ERK proteins (1). We have shown that the TGF-β-mediated signaling pathway also includes generation of recurring oscillations in [Ca2+], which in turn stimulate CaMK-II activity (indicated by autophosphorylation of CaMK-II) (21). Treatment with PGE2 before TGF-β did not alter TGF-β-induced phosphorylation of SMAD-2 and ERK proteins, but phosphorylation of Akt and CaMK-II was significantly reduced (P < 0.005 and P < 0.05, respectively) in normal HPFs treated with PGE2 (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

PGE2 interferes with transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling. A: Western blots show phosphorylation of Smad-2, Akt, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMK-II), or ERK in control-human pulmonary fibroblasts (HPFs) in the absence and presence of treatment with TGF-β (1 nM; overnight) and/or PGE2 (500 nM; added 30 min before TGF-β), as indicated. Figures are representative images of three different groups, and each experiment was repeated at least three times. Scatterplots (right) indicate mean ±SE levels of phosphorylated protein/total protein after treatment with TGF-β and/or PGE2; n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005. B: confocal fluorimetric tracings obtained from a control-HPF treated with TGF-β (1 nM, overnight; left) and an untreated idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)-HPF (right), both showing [Ca2+] oscillations that are abrogated by 500 nM PGE2. C: normal-HPF treated overnight with TGF-β (as above) and an IPF-HPF, both pretreated with PGE2 (as indicated) and both showing absence of [Ca2+] oscillations. Tracings are representative of >10 cells.

Likewise, the [Ca2+] oscillations observed in normal HPFs incubated with TGF-β (1 nM, overnight), as well as “basally” in IPF HPFs, were eliminated within minutes following treatment with 500 nM PGE2 (Fig. 2B). We also did not find [Ca2+] oscillations in normal HPFs or IPF-HPFs that were incubated overnight with TGF-β together with PGE2 (Fig. 2C).

Defining the receptor(s) that mediate the effects of PGE2 on HPFs.

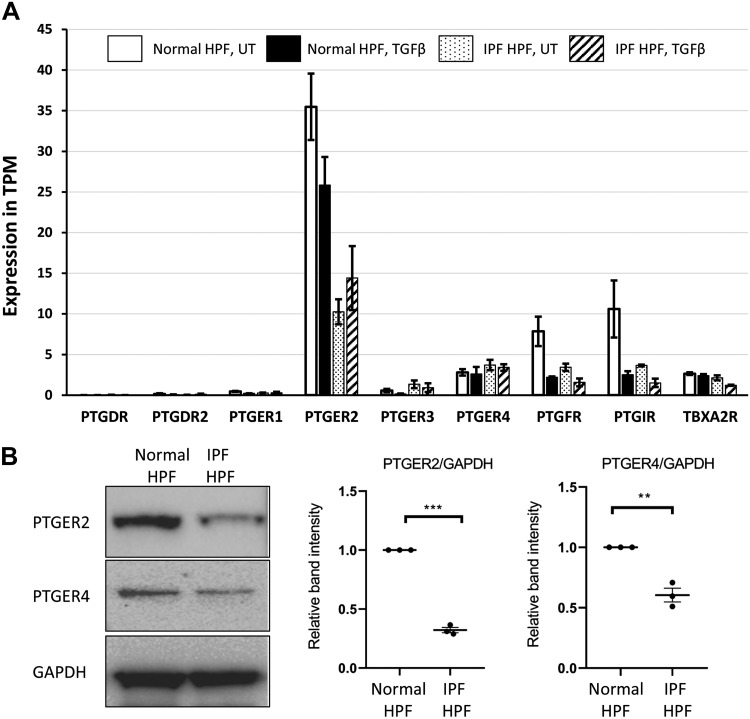

RNA sequencing (RNAseq) analysis of normal-HPFs revealed a prominent expression of EP2 receptors with lower expression of EP4 receptors and barely discernible expression of EP1 or EP3 receptors (Fig. 3). We also found moderate expression of receptors for prostaglandins F2α (FP) and I2 (IP), and for thromboxane A2 (TP) (Fig. 3). EP2-receptor expression in IPF-HPFs was reduced ~3.5 fold [false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05] compared with that of normal HPFs, but expression of EP3, EP4, FP, IP, and TP receptors in IPF-HPFs was not significantly different from that of normal HPFs. Treatment of both normal and IPF-derived HPFs with TGF-β (1 nM, overnight) significantly reduced the expression of FP and IP receptors, by approximately threefold, with FDR <0.05. The EP2 receptor is the highest expressed Gs-coupled GPCR in HPFs (most prominently so in normal HPFs), highlighting the specific importance of the EP2 receptor in these cells. Prostanoid receptors (the EP2, IP, and EP4 receptors) account for three of the four highest expressed Gs-coupled GPCRs in HPFs.

Fig. 3.

Expression of EP receptors in human pulmonary fibroblasts (HPFs). A: RNA sequencing data for expression of various prostanoid receptors in samples of normal HPFs or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)-HPFs in the absence [untreated (UT)] or presence of overnight treatment with transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β; 1 nM), as indicated. TPM, transcripts per million. Bar diagrams indicate mean ±SE values of relative gene expressions; n = 3. B: Western blots show that EP2- and EP4-receptor protein levels were reduced in IPF-HPFs compared with normal-HPFs. Figures are representative images of three different groups, and each experiment was repeated at least three times. Scatterplots indicate mean ±SE values of relative band intensities. Values are normalized against normal-HPF group; n = 3. **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005.

Western blot analysis also confirmed that EP2- and EP4-receptor protein levels are high in normal HPFs. The levels of EP2 or EP4 proteins were reduced ~3.5- and ~1.5-fold, respectively, in IPF-HPFs (Fig. 3B).

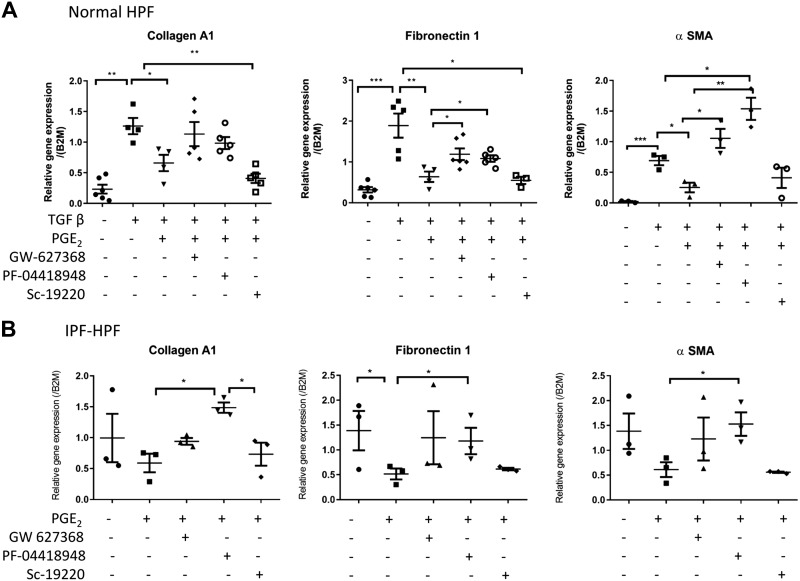

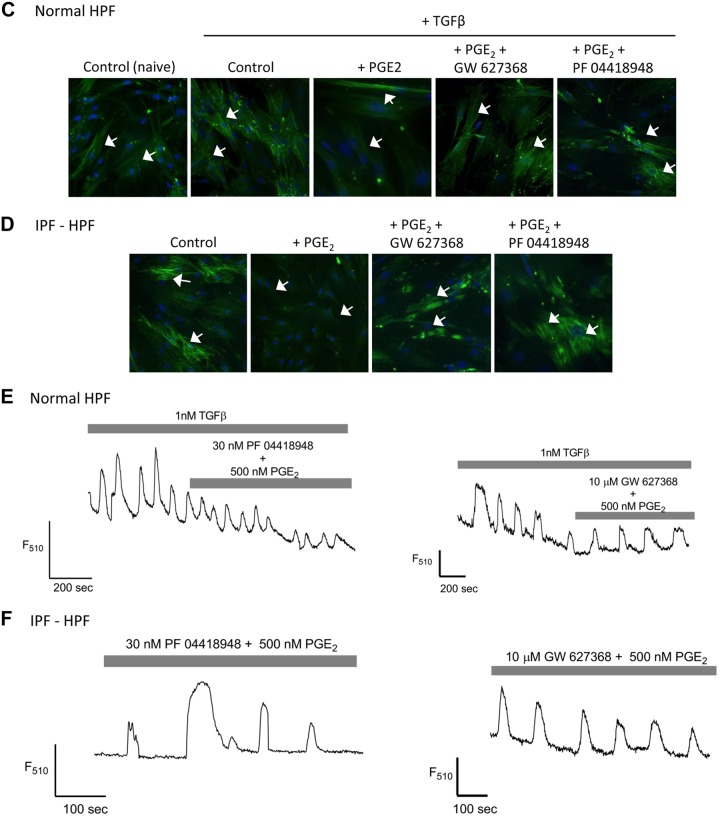

We next tested the role of the receptors for PGE2 in mediating its antifibrotic effects. Figure 4, A and B, shows that the expression of collagen A1, fibronectin, and α-SMA genes induced by TGF-β (1 nM, overnight) was greatly reduced by PGE2 in normal HPFs (Fig. 4A) and HPFs from IPF patients (Fig. 4B). These PGE2-promoted responses were reduced by selective antagonists of EP2 (PF 04418948, 30 nM) or EP4 (GW627368, 10 µM) but not EP1 (SC-19220, 100 µM) receptors. Additionally, the PGE2-induced reduction of filamentous α-SMA expression in TGF-β-treated (1 nM, 48 h) normal HPFs or untreated IPF-HPFs was blocked by treatment with PF 04418948 (30 nM, 15 min before PGE2 treatment) or GW627368 (10 μM, 15 min before PGE2 treatment) (Fig. 4, C and D).

Fig. 4.

Antagonism of PGE2-promoted effects in human pulmonary fibroblasts (HPFs). A and B: expression of collagen A1, fibronectin, and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) mRNA in transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-treated (1 nM, overnight) control-HPFs (A) or in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)-HPFs (B) is reduced by PGE2 (500 nM, added 30 min before TGF-β). The PGE2-promoted reduction in the mRNA is blocked by the EP2-selective antagonist PF 04418948 (30 nM) or the EP4-selective antagonist GW627368 (10 µM) but not by the EP1-selective antagonist SC-19220 (100 μM). Scatterplots indicate mean (±SE) values of relative gene expression; n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005. C: immunofluorescence of control-HPFs showing inhibition by PGE2 of TGF-β (1 nM, 48 h)-induced stress fiber formation (white arrows), and blockade of this inhibition by treatment with the EP2-selective PF 04418948 (30 nM, 15 min before PGE2 treatment) or the EP4-selective GW627368 (10 μM, 15 min before PGE2 treatment). D: similar findings occurred with IPF-HPFs . White arrows (C and D) indicate α-SMA filaments and blue stain (DAPI) indicate nucleus. Immunofluorescence data (C and D) shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments using different cell culture wells (each well contained cells derived from different unique donors). Photomicrographs were taken at the same setting (×20 zoom) and exposure time for all pictures. E and F: confocal fluorimetric tracings showing that coadministration of PGE2 and PF 04418948 (30 nM) or GW627368 (10 µM) did not alter recurring [Ca2+] oscillations in TGF-β-treated control-HPF (E) or in an IPF-HPF (F) (cf. Fig. 2, B and C).

Fig. 4.

Continued

PF 04418948 (30 nM) and GW627368 (10 µM) also blocked the inhibition of [Ca2+] oscillations by PGE2 in TGF-β-treated normal HPFs or observed basally in IPF-HPFs (Fig. 4, E and F).

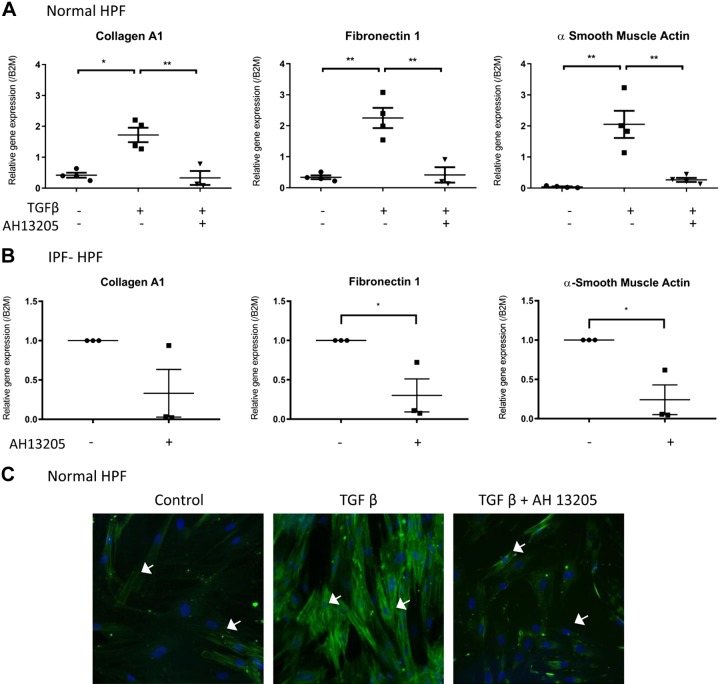

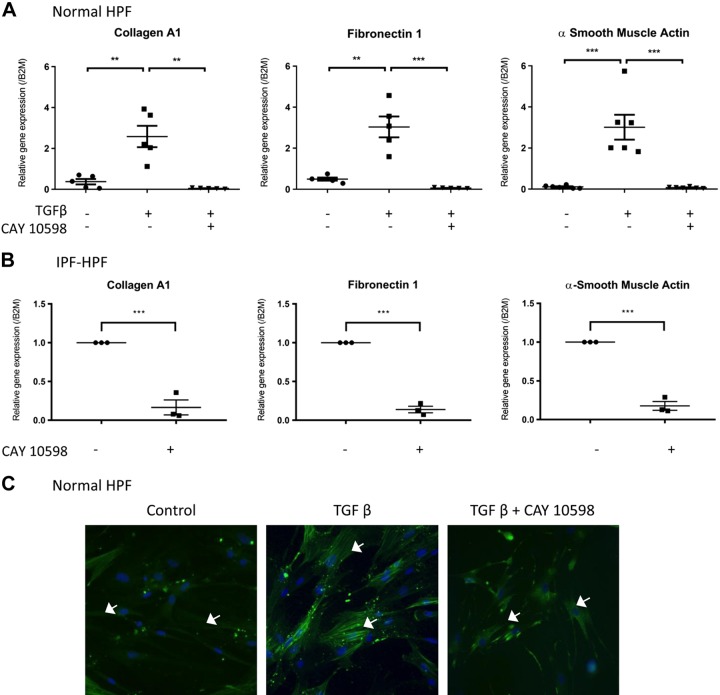

The EP2-selective agonist AH13205 and the EP4-selective agonist CAY10598 (both 10 μM, 30 min before overnight treatment with 1 nM TGF-β) mimicked the inhibitory effect of PGE2 on the expression of collagen A1, fibronectin-1, or α-SMA genes and α-SMA protein expression in TGF-β-treated control HPFs (Fig. 5, A and C, and Fig. 6, A and C) or unstimulated IPF-HPFs (Figs. 5B and 6B).

Fig. 5.

Selective agonism of PGE2-mediated effects in human pulmonary fibroblasts (HPFs). A: The EP2-selective agonist AH13205 [added 30 min before transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) treatment] mimics the inhibitory effects of PGE2 on TGF-β-induced expression of collagen A1 (left), fibronectin (middle) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; right) assessed 24 h after treatment with TGF-β (1 nM). B: similar results were obtained with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)-HPFs. Scatterplots indicate mean (±SE) values of relative gene expressions; for IPF-HPFs, gene expression values were normalized against control group; n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005. C: immunofluorescence, showing that TGF-β-induced stress fiber formation is reduced by the EP2-selective agonist AH13205 (10 μM; 30 min before 48 h 1 nM TGF-β-treatment). White arrows (C) indicate α-SMA filaments and blue stain (DAPI) indicate nucleus. Immunofluorescence data shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments using different cell culture wells (each well representing a different donor). Photomicrographs were all taken at the same setting (×20 zoom) and exposure time.

Fig. 6.

Selective agonism of PGE2-mediated effects. A: the EP4-selective agonist CAY 10598 [10 μM, 30 min before 1-nM transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) treatment] mimics the inhibitory effects of PGE2 upon TGF-β-induced expression of collagen A1 (left), fibronectin (middle) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; right) after overnight TGF-β (1 nM) treatment. B: similar observations were made in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)-human pulmonary fibroblasts (HPFs). Scatterplots indicate mean (±SE) values of relative gene expressions; for IPF-HPFs, gene expression values were normalized against control group; n = 3. **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005. C: immunofluorescence, showing that TGF-β-induced stress fiber formation is reduced by the EP4-selective agonist CAY 10598 (10 μM, 30 min before 48 h 1-nM TGF-β treatment). White arrows (C) indicate α-SMA filaments and blue stain (DAPI) indicate nucleus. Immunofluorescence data shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments using different cell culture wells (each well representing a different donor). Photomicrographs were all taken at the same setting (×20 zoom) and exposure time.

Effects of PGE2 on HPFs are mimicked by increases in cAMP.

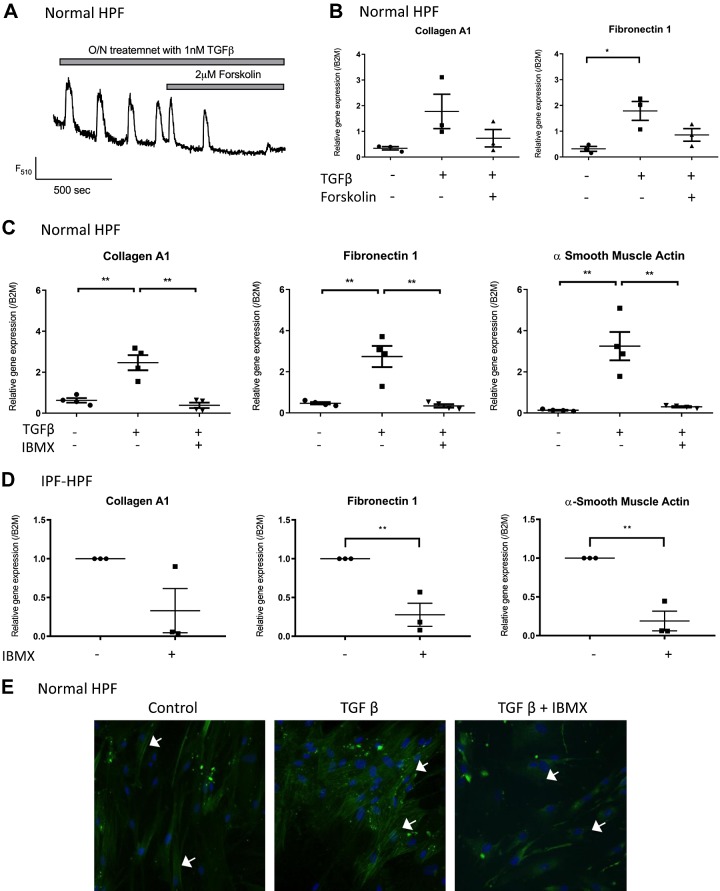

EP2 and EP4 receptors exert their actions through activation of the Gs protein that increases AC activity and cellular cAMP concentrations (6). Consistent with this idea, we found that the inhibitory effects of PGE2 on TGF-β-stimulated [Ca2+] oscillations (Fig. 7A) and expression of collagen A1 and fibronectin-1 (Fig. 7B) were mimicked by 2 µM forskolin, an AC activator. Likewise, 3-isobutyl-1-methyl (IBMX; 10 µM), a cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase inhibitor that prevents the degradation of endogenously generated cAMP, thereby leading to its accumulation, mimicked the inhibitory effect of PGE2 on TGF-β-promoted expression of collagen A1, fibronectin-1 and α-SMA genes (Fig. 7C) and α-SMA protein expression (Fig. 7E) in normal HPFs and expression of those genes in IPF-HPFs (Fig. 7D). Together these findings imply that the actions of PGE2, acting via EP2 and EP4 receptors, occur via increases in cAMP.

Fig. 7.

A and B: PGE2-mediated effects involve cAMP. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (1 nM)-induced [Ca2+] oscillations (A) and expression of extracellular matrix proteins (B) are suppressed by forskolin [2 µM, 30 min before transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) treatment]. C and D: isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX; 10 μM, 30 min before TGF-β-treatment) suppressed TGF-β-induced expression of ECM genes [left: collagen A1; middle: fibronectin; right: α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in normal HPFs (C)] and decreased the expression of those same extracellular matrix genes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)-HPFs (D). Scatterplots indicate mean (±SE) values of relative gene expressions; for IPF-HPFs, gene expression values were normalized against control group; n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005. E: actin stress fiber (white arrows) formation is also suppressed by IBMX. Immunofluorescence data shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments using different cell culture wells (each well representing a different donor). Photomicrographs were all taken at the same setting (×20 zoom) and exposure time.

DISCUSSION

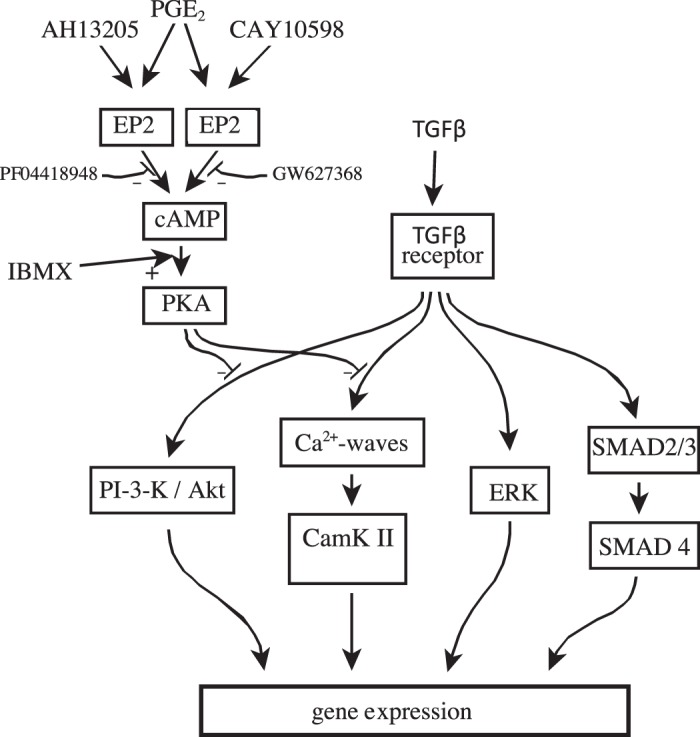

In this study, we characterized the inhibition by PGE2 of the profibrotic effects of TGF-β in normal HPFs as well as those, which are activated “basally” in IPF-HPFs. Our data show that the [Ca2+] oscillations and elevated biosynthesis of ECM proteins evoked in normal cells following TGF-β-stimulation are already present in the IPF cells at “baseline” and furthermore that both functional responses are brought back down by PGE2 or its analogs to the basal levels seen in unstimulated/normal cells. They further show that PGE2 also inhibits Akt and CaMK-II activation but does not alter phosphorylation of SMAD2 or ERK (see Fig. 8). We believe the current findings are disease relevant since [Ca2+] oscillations alone are necessary and sufficient to stimulate ECM protein expression in HPFs (21).

Fig. 8.

Overall schematic. Flow diagram integrating the findings of this study with previously published data. CaMK-II, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

These data corroborate and extend previous findings regarding the actions of PGE2 in HPFs via EP2 receptors and stimulation of the cAMP/PKA-signaling pathway (5, 14, 30). Our RNAseq and Western blot data provide a potentially important mechanistic clue in understanding the changes in pulmonary fibrosis. We found that EP2 receptors are the most highly expressed prostanoid receptor subtype in HPFs and that EP2 receptor expression is significantly lower in IPF-HPFs than in control HPFs.

It has been suggested that HPFs can generate PGE2 in response to proinflammatory stimuli, perhaps as part of an autocrine restorative process (see below) (12, 13). If so, the decrease in EP2-receptor expression in response to TGF-β stimulation and in IPF may contribute to the pathobiology of IPF and other fibrotic disorders in the lung. Of note, EP2- and EP4-receptor proteins are downregulated in COPD (3). However, Oga et al. (22) reported that genetic knockdown of EP2 receptors did not affect pulmonary fibrotic changes in a murine bleomycin model. One might have expected the latter to be exacerbated in the EP2-knockdown mice if EP2 signaling blunts profibrotic changes. However, we show here that expression of EP2 receptors is substantially reduced in HPFs when TGF-β levels are elevated (following exogenous addition) or in IPF, so the potentially beneficial effects of endogenous PGE2 may have been obviated by the bleomycin treatment, which is known to elevate levels of TGF-β (18).

Further supporting the idea that EP2 agonism may be a beneficial antifibrotic treatment, Kach et al. (7) have shown that noscapine can prevent differentiation of HPFs into myofibroblasts and ameliorate an experimental model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, by activating EP2 receptors and stimulating PKA. Thus, in addition to its ability to disrupt tubulin function (which has made it useful for treating tumors), noscapine activates PKA in HPFs through a pathway that is blocked by PF-04418948 (EP2 selective) but not by blockers of EP4 or DP receptors (using L-161,982 or BW A868C, respectively).

Our data suggest that EP4 receptors may also contribute to the inhibition by PGE2 of ECM protein expression. A previous study noted that the antifibrotic contribution of EP4 receptors is less than that of EP2 receptors (5). This difference in functional response may derive from the ~10-fold lower expression of EP4 receptors than EP2 receptors revealed by our RNAseq analysis. Huang et al. (5) used RT-PCR to show that EP4-mRNA levels were negligible while those of EP2-mRNA were substantial and three or four times higher than those of the EP1 or EP3 subtypes. Our RT-PCR and RNAseq data are consistent with those findings.

In spite of the lower mRNA expression of EP4 receptors, we found that both EP2- and EP4-selective antagonists were roughly equivalent in blunting PGE2-mediated antifibrotic effects and that the EP4-selective agonist CAY 10598 reduced the elevated levels of ECM protein expression in IPF-HPFs to a similar extent as did the EP2-selective agonist AH 13205. Both selective agonists reduced expression to a level comparable to, or even lower than, that of unstimulated, nondiseased HPFs. Adding to the potential clinical relevance of these findings is that, unlike what occurred with EP2 receptors, EP4-receptor expression was not altered in IPF-HPFs or in control HPFs treated with TGF-β.

EP2 and EP4 receptors exert their physiological actions through cAMP: we show here that the inhibitory effect of PGE2 upon [Ca2+] oscillations was mimicked by IBMX or by forskolin, both of which elevate cAMP levels. The two major effectors for cAMP are protein kinase A (PKA) and exchange protein activated by cAMP-1 (Epac-1) (6). Only a PKA-selective agonist was able to reduce collagen expression in HPFs (5). Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of PGE2 upon collagen-secretion in HPFs was attenuated by selective knockdown of only one of four different PKA-regulatory subunit isoforms (PKAR-Iβ) and mimicked only by a selective agonist of PKAR-Iβ (30). On the other hand, PGE2-stimulated expression of α-SMA in HPFs was selectively attenuated by knock down of a different PKA-regulatory subunit isoform (PKAR-IIβ) and a cAMP-analog that selectively activates PKAR-IIβ exclusively inhibited HPF differentiation. Wettlaufer et al. went on to find the downstream targets of PKAR-Iβ-stimulated PKA activity include protein kinase B (AKT) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), whereas those of PKAR-IIβ-stimulated PKA activity include differentiation-associated phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase and serum response factor.

Lacy et al. (12, 13) have recently shown that proinflammatory stimuli cause HPFs to upregulate COX-2 expression and generate/release substantial amounts of PGD2 and PGE2. In contrast to these observations made in human cells, in a murine model (bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis) PGE2 production increased more than fivefold, whereas that of other prostanoid species (including PGD2) and arachidonic acid metabolites was less than doubled or even unchanged (22). Lacy et al. (12, 13) also found that PGD2 and PGE2 act in an autocrine/paracrine fashion to prevent the conversion of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and attenuate TGF-β-induced HPF proliferation without affecting HPF viability, and that pharmacological inhibition of PGD2 production was as effective as selective inhibition of PGE2 production. Perhaps PGD2 does not act via DP receptors, given that our RNAseq analysis indicates those receptors are barely detectable in HPFs. Prostanoid receptors can respond to a variety of prostanoids at various concentrations but respond to the greatest extent to the particular species for which each is named. EP2 receptors are activated by PGD2 at concentrations only~10-fold higher than those of PGE2 (32). In addition, PGD2 and several of its metabolites, including 15d-PGJ2, can signal through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) and HPFs produce several PPAR-γ ligands under proinflammatory conditions (13). Stimulation of PPAR-γ also exerts antifibrotic actions in HPFs by suppressing PI3K-Akt signaling (11).

In conclusion, we find that PGE2 inhibits expression of ECM genes and conversion of fibroblasts to a myofibroblast phenotype (i.e., increased α-SMA expression and organization into stress fibers) in normal, TGF-β-treated HPFs and basally in IPF-HPFs. This inhibitory effect of PGE2 appears to occur via EP2- and apparently also EP4-receptor-generated cAMP, which blunts [Ca2+] oscillations promoted by TGF-β or present in IPF-HPFs and inhibits activation of CaMK-II. Although Akt may be affected by PGE2, Smad-proteins and ERK are not. A decreased expression of EP2 receptors in IPF-HPFs implies a pathophysiologic role for this decrease in EP2 receptors and identifies potential therapeutic strategies involving EP2 and perhaps EP4 receptors for the treatment of IPF.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant CIHR136848-MOP-RS), the Ontario Thoracic Society and Toronto-Dominion Grant in Medical Excellence Award, St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton, National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant T32 HL-098062-04), U.S. Department of Defense (W81XWH-14-1-0372), and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.M., P.A.I., and L.J.J. conceived and designed research; S.M., W.S., A.M., K.S., and R.S. performed experiments; S.M., W.S., A.M., K.S., A.D.-G., and L.J.J. analyzed data; S.M., A.M., K.S., P.A.I., and L.J.J. interpreted results of experiments; S.M., A.M., and K.S. prepared figures; S.M. and L.J.J. drafted manuscript; S.M., W.S., A.M., K.S., P.A.I., and L.J.J. edited and revised manuscript; S.M., W.S., A.M., K.S., R.S., A.D.-G., P.A.I., and L.J.J. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the technical support from Fuqin Duan.

Present addresses: S. Mukherjee, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Univ. of Toronto, Toronto, ON, M4N 3M5, Canada; W. Sheng, Univ. of Toronto, Toronto, ON; R. Sun, Meakins-Christie Laboratories, The Research Institute of the McGill Univ. Health Centre, Montreal, QC, H4A 3J1, Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society . American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 277–304, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aschner Y, Downey GP. Transforming growth factor-β: master regulator of the respiratory system in health and disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 54: 647–655, 2016. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0391TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonanno A, Albano GD, Siena L, Montalbano AM, Riccobono L, Anzalone G, Chiappara G, Gagliardo R, Profita M, Sala A. Prostaglandin E2 possesses different potencies in inducing vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-8 production in COPD human lung fibroblasts. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 106: 11–18, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, Pachter L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol 34: 525–527, 2016. [Erratum in Nat Biotechnol 34: 888, 2016.] doi: 10.1038/nbt.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang S, Wettlaufer SH, Hogaboam C, Aronoff DM, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits collagen expression and proliferation in patient-derived normal lung fibroblasts via E prostanoid 2 receptor and cAMP signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L405–L413, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00232.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang J, Qiu J, Li Q, Shi Z. Prostaglandin E2 signaling: alternative target for glioblastoma? Trends Cancer 3: 75–78, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kach J, Sandbo N, La J, Denner D, Reed EB, Akimova O, Koltsova S, Orlov SN, Dulin NO. Antifibrotic effects of noscapine through activation of prostaglandin E2 receptors and protein kinase A. J Biol Chem 289: 7505–7513, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.546812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katzenstein AL, Myers JL. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: clinical relevance of pathologic classification. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 157: 1301–1315, 1998. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9707039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khalil N, O’Connor RN, Unruh HW, Warren PW, Flanders KC, Kemp A, Bereznay OH, Greenberg AH. Increased production and immunohistochemical localization of transforming growth factor-beta in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 5: 155–162, 1991. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/5.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuang E, Wu F, Zhu F. Mechanism of sustained activation of ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) and ERK by kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF45: multiprotein complexes retain active phosphorylated ERK AND RSK and protect them from dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem 284: 13958–13968, 2009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900025200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kulkarni AA, Thatcher TH, Olsen KC, Maggirwar SB, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. PPAR-γ ligands repress TGFβ-induced myofibroblast differentiation by targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway: implications for therapy of fibrosis. PLoS One 6: e15909, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacy SH, Epa AP, Pollock SJ, Woeller CF, Thatcher TH, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Activated human T lymphocytes inhibit TGFβ-induced fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation via prostaglandins D2 and E2. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 314: L569–L582, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00565.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lacy SH, Woeller CF, Thatcher TH, Maddipati KR, Honn KV, Sime PJ, Phipps RP. Human lung fibroblasts produce proresolving peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ ligands in a cyclooxygenase-2-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 311: L855–L867, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00272.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambers C, Roth M, Jaksch P, Muraközy G, Tamm M, Klepetko W, Ghanim B, Zhao F. Treprostinil inhibits proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition by fibroblasts through cAMP activation. Sci Rep 8: 1087, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19294-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lederer DJ, Martinez FJ. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 378: 1811–1823, 2018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1705751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L, Liu X, Ren X, Tian Y, Chen Z, Xu X, Du Y, Jiang C, Fang Y, Liu Z, Fan B, Zhang Q, Jin G, Yang X, Zhang X. Smad2 and Smad3 have differential sensitivity in relaying TGFβ signaling and inversely regulate early lineage specification. Sci Rep 6: 21602, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep21602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo LJ, Liu F, Wang XY, Dai TY, Dai YL, Dong C, Ge BX. An essential function for MKP5 in the formation of oxidized low density lipid-induced foam cells. Cell Signal 24: 1889–1898, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukherjee S, Ayaub EA, Murphy J, Lu C, Kolb M, Ask K, Janssen LJ. Disruption of calcium signaling in fibroblasts and attenuation of bleomycin-induced fibrosis by nifedipine. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 53: 450–458, 2015. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0009OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukherjee S, Duan F, Kolb MR, Janssen LJ. Platelet derived growth factor-evoked Ca2+ wave and matrix gene expression through phospholipase C in human pulmonary fibroblast. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45: 1516–1524, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukherjee S, Kolb MR, Duan F, Janssen LJ. Transforming growth factor-β evokes Ca2+ waves and enhances gene expression in human pulmonary fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 46: 757–764, 2012. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0223OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukherjee S, Sheng W, Sun R, Janssen LJ. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIβ and IIδ mediate TGFβ-induced transduction of fibronectin and collagen in human pulmonary fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 312: L510–L519, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00084.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oga T, Matsuoka T, Yao C, Nonomura K, Kitaoka S, Sakata D, Kita Y, Tanizawa K, Taguchi Y, Chin K, Mishima M, Shimizu T, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin F2α receptor signaling facilitates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis independently of transforming growth factor-β. Nat Med 15: 1426–1430, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nm.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penke LR, Huang SK, White ES, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits α-smooth muscle actin transcription during myofibroblast differentiation via distinct mechanisms of modulation of serum response factor and myocardin-related transcription factor-A. J Biol Chem 289: 17151–17162, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.558130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raghu G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: lessons from clinical trials over the past 25 years. Eur Respir J 50: 1701209, 2017. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01209-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Bradford WZ, Oster G. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174: 810–816, 2006. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-163OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26: 139–140, 2010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sgalla G, Iovene B, Calvello M, Ori M, Varone F, Richeldi L. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: pathogenesis and management. Respir Res 19: 32, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0730-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soneson C, Love MI, Robinson MD. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000 Res 4: 1521, 2015. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7563.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker NM, Badri LN, Wadhwa A, Wettlaufer S, Peters-Golden M, Lama VN. Prostaglandin E2 as an inhibitory modulator of fibrogenesis in human lung allografts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185: 77–84, 2012. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201105-0834OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wettlaufer SH, Penke LR, Okunishi K, Peters-Golden M. Distinct PKA regulatory subunits mediate PGE2 inhibition of TGFβ-1-stimulated collagen I translation and myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 313: L722–L731, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00131.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White ES, Atrasz RG, Dickie EG, Aronoff DM, Stambolic V, Mak TW, Moore BB, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits fibroblast migration by E-prostanoid 2 receptor-mediated increase in PTEN activity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 32: 135–141, 2005. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0126OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woodward DF, Jones RL, Narumiya S. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXIII: classification of prostanoid receptors, updating 15 years of progress. Pharmacol Rev 63: 471–538, 2011. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu ML, Chen CH, Lin YT, Jheng YJ, Ho YC, Yang LT, Chen L, Layne MD, Yet SF. Divergent signaling pathways cooperatively regulate TGFβ induction of cysteine-rich protein 2 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cell Commun Signal 12: 22, 2014. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-12-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiang T, Ohashi A, Huang Y, Pandita TK, Ludwig T, Powell SN, Yang Q. Negative regulation of AKT activation by BRCA1. Cancer Res 68: 10040–10044, 2008. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]