Abstract

Intrauterine growth-restricted (IUGR) fetal sheep have increased hepatic glucose production (HGP) that is resistant to suppression during a hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp (insulin clamp). We hypothesized that the IUGR fetal liver would have activation of metabolic and signaling pathways that support HGP and inhibition of insulin-signaling pathways. To test this, we used transcriptomic profiling with liver samples from control (CON) and IUGR fetuses receiving saline or an insulin clamp. The IUGR liver had upregulation of genes associated with gluconeogenesis/glycolysis, transcription factor regulation, and cytokine responses and downregulation of genes associated with cholesterol synthesis, amino acid degradation, and detoxification pathways. During the insulin clamp, genes associated with cholesterol synthesis and innate immune response were upregulated in CON and IUGR. There were 20-fold more genes differentially expressed during the insulin clamp in IUGR versus CON. These genes were associated with proteasome activation and decreased amino acid and lipid catabolism. We found increased TRB3, JUN, MYC, and SGK1 expression and decreased PTPRD expression as molecular targets for increased HGP in IUGR. As candidate genes for resistance to insulin’s suppression of HGP, expression of JUN, MYC, and SGK1 increased more during the insulin clamp in CON compared with IUGR. Metabolites were measured with 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance and support increased amino acid concentrations, decreased mitochondria activity and energy state, and increased cell stress in the IUGR liver. These results demonstrate a robust response, beyond suppression of HGP, during the insulin clamp and coordinate responses in glucose, amino acid, and lipid metabolism in the IUGR fetus.

Keywords: developmental programming, fetus, gluconeogenesis, insulin resistance, liver

INTRODUCTION

Intrauterine insults, including intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), can increase the life-long risk for metabolic diseases, including type 2 diabetes (T2DM) (3, 19, 32, 35). Our data in fetal sheep with IUGR induced by placental insufficiency demonstrate an early activation of hepatic glucose production (HGP), increased hepatic gluconeogenic gene expression, and resistance to insulin’s normal suppression of HGP (47). This is liver-specific insulin resistance because the IUGR fetus has a robust increase in nonhepatic insulin-stimulated glucose utilization (11, 29, 31, 47, 49, 53, 54). Thus, the liver may be one of the first organs to develop insulin resistance beginning in utero as a result of IUGR (49). This is important because increased HGP and insulin resistance, both hallmarks of T2DM (44), may underlie the increased predisposition for T2DM that is characteristic of IUGR offspring. However, the impact of IUGR on other pathways in the fetal liver is not fully known.

During placental insufficiency, the fetus receives decreased supplies of nutrients and oxygen and develops decreased blood oxygenation, decreased plasma glucose and insulin concentrations, and increased counter-regulatory hormone concentrations, which likely produce coordinated changes in metabolic pathways to support HGP. Indeed, we and others have shown increased expression of the major gluconeogenic genes, including PCK1, PCK2, G6PC, and PC and increased expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) in the IUGR liver (6, 15, 47). This suggests that the liver has reduced hepatic glucose oxidation and increased intrahepatic production of lactate during IUGR (55). However, evidence of changes in metabolite abundance that support this metabolic coordination has not been identified in the IUGR fetal liver.

The molecular mechanisms underlying the early activation of HGP and resistance to suppression with insulin in the IUGR fetus are not fully understood. In the adult under normal conditions, insulin-mediated AKT signaling suppresses HGP via phosphorylation and inactivation of the forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) protein (17). Our previous data demonstrate increased phosphorylation of AKT in both control (CON) and IUGR fetal livers during the hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp (insulin clamp) (47). However, in the IUGR liver under basal and insulin clamp conditions, we observed increased nuclear localization and phosphorylation of FOXO1 (T24). This suggests increased activity of FOXO1 that is persistent despite normal insulin action on AKT signaling and is supported by increased expression of FOXO1 target genes, including PCK1, IGFBP1, and PGC1A in the IUGR fetal liver (47). Different posttranslational modifications regulate FOXO1 transcriptional activity and nuclear localization with some causing nuclear exclusion and inactivation (i.e., via AKT) and others resulting in nuclear retention with maintained activation [i.e., via JNK (c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase)] (21). Phosphorylation of nuclear JNK protein is increased in the IUGR fetal liver during the insulin clamp (47). Activation of JNK and subsequent aberrant FOXO1 activation may be involved in the early activation of HGP and resistance to insulin in the IUGR fetal liver. However, additional signals are likely involved in the activation of JNK, FOXO1, and HGP in the IUGR fetal liver that have yet to be identified. Furthermore, in addition to suppressing HGP, insulin activates anabolic pathways, including protein and lipid synthesis in the adult liver (39, 51). However, little is known about insulin action on these anabolic pathways in normal or IUGR fetuses in late gestation.

Our objective was to determine the effects of IUGR and insulin on molecular and metabolic pathways in the fetal liver. Specifically, we aimed to identify genes and pathways underlying the early activation of HGP and resistance to suppression with insulin in the IUGR fetal liver. We also aimed to identify novel metabolic and regulatory pathways altered in the IUGR fetal liver and to determine the differential response between control and IUGR fetal livers during the insulin clamp. To accomplish this, we used gene expression microarray profiling to measure transcriptional regulation and 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) to measure metabolites. We validated specific genes and proteins in pathways of interest using quantitative PCR and Western blotting, respectively. We used liver samples from control and IUGR fetal sheep collected under saline and insulin clamp conditions. The insulin clamp was used to test the specific effect of increased insulin concentrations independent of changes in glucose concentrations. Importantly, sophisticated metabolic studies using this insulin clamp method can only be performed in the fetus using large animal models like the sheep (36). Overall, this approach allowed us to determine mechanisms that underlie increased HGP under basal conditions and mechanisms for resistance to insulin’s suppression of HGP during the insulin clamp.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fetal Sheep Model of IUGR and Fetal Insulin Clamp Study

Liver samples used here were part of published studies testing the effect of IUGR and the acute insulin clamp on metabolic and physiological outcomes (7, 47). The methods to produce these fetuses and the in utero experimental conditions are briefly described below. All sample sizes are indicated in the tables and figure legends. Experiments were designed and reported with reference to the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (26).

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Colorado. Pregnant Columbia-Rambouillet ewes were studied at the Perinatal Research Center, Aurora, CO, which is accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. IUGR fetuses were created by exposing pregnant ewes to elevated humidity and temperature (40°C for 12 h, 35°C for 12 h) from ~37 days gestation age (dGA; term = ~147 dGA) to ~116 dGA in an environmentally controlled room as previously described (47). CON fetuses were from pregnant ewes exposed to normal humidity and temperatures daily (25°C) in an environmentally controlled room and pair fed to the intake of the IUGR ewes. After treatment, all ewes were exposed to normal humidity and temperatures until time of study. Fetuses were surgically instrumented with indwelling catheters placed in the umbilical vein, descending aorta, and femoral veins at ~125 dGA. All ewes were carrying singleton pregnancies except for one CON carrying twins of normal birth weight. In this case, only one fetus was catheterized for study, and the other fetus was used for collection of basal tissue samples and included in the CON + SAL group. No differences have been found with this twin relative to singletons in our other analyses (47).

A fetal insulin clamp or saline infusion (basal) was performed at ~132 dGA in CON and IUGR fetuses to create four groups: CON + basal, CON + clamp, IUGR + basal, and IUGR + clamp (7, 47). Each fetus was studied during a basal period, immediately followed by second period with the insulin clamp or saline infusion. For each study period, four steady-state blood samples, ~10–15 min apart, were drawn simultaneously from the fetal artery and umbilical vein. The insulin clamp was performed over 3 h using 3 mU·min−1·kg−1 of insulin, a maximal dose for glucose utilization and suppression of HGP in the sheep fetus (20), and variable infusions of glucose and amino acids (Trophamine) (7, 47). Fetal arterial plasma glucose and branched chain amino acid concentrations were monitored every 10–15 min, and infusion rates were adjusted to match each fetus’ own mean arterial glucose and branched chain amino acid concentration observed during the basal period. Under saline infusion or insulin clamp conditions, the fetus was euthanized, and liver samples were collected.

Gene Expression Microarray Analysis

Gene expression data were collected at the Genomics and Microarray Core of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus using Affymetrix protocols and equipment for GeneChip Bovine Genome Arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The array contained ~23,000 genes (24,027 probe sets). RNA was isolated from CON + basal, CON + clamp, IUGR + basal, and IUGR + clamp liver tissue (n = 3 each) following homogenization in TRIzol and extraction using Qiagen RNeasy columns with on-column DNase (6, 47, 48). RNA quality and integrity were assessed using BioRad Experion, and all samples had RNA quality scores >9.0. Total RNA (300 ng) was primed with T7 oligo primer to synthesize cDNA. Single-stranded cDNA was converted to double-stranded DNA template for transcription. The cDNA was used directly in the in vitro transcription reaction to synthesize Biotin-Modified cRNA. cRNA (10 μg) was hybridized on the Affymetrix Bovine Gene Chip with rotation at 60 revolutions/min for 16 h at 45°C. Chips were washed and scanned using a GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 and scanned using a GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix). Scanned chip images were analyzed and normalized with the robust multiarray average method using Affymetrix Expression Console Software. Gene expression data have been deposited (GSE114580; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

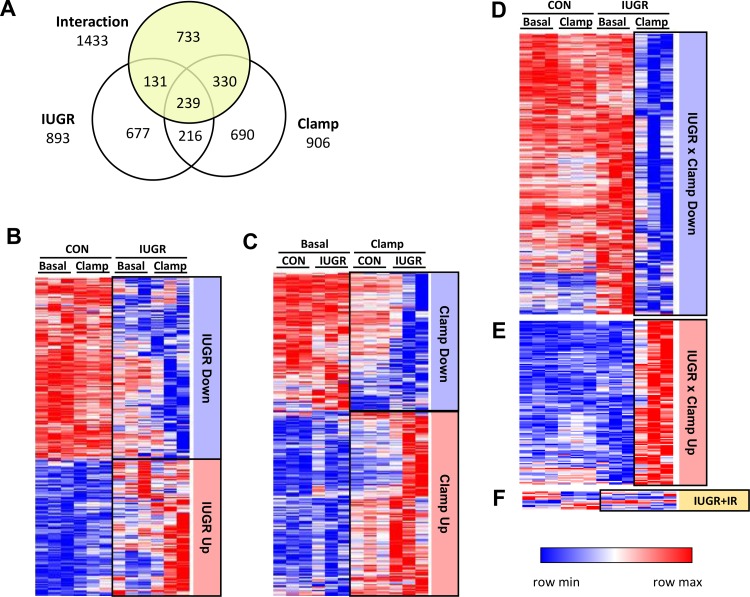

Normalized data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with main effects of IUGR (CON vs. IUGR) and insulin clamp (basal vs. insulin clamp) and an interaction effect using GeneSpring Software. First, we identified all genes with a significant (P < 0.05) main effect of IUGR (n = 4,831), main effect of insulin clamp (n = 7,018), or interaction effect (n = 2,474). The false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated for each of these groups using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (2). In the IUGR group, all genes met an FDR of 24.9%. In the insulin clamp group, all genes met an FDR of 17.2%. In the interaction group, only 131 genes met an FDR <25%. Second, we filtered each of these three groups of genes to include only those with an absolute fold change >1.5 for either the main effect of IUGR (n = 1,263) or insulin clamp (n = 1,475) or a posttest comparison in interaction group (n = 1,433) to represent genes with the most potential impact based on magnitude of differential expression. Third, these three lists of genes were sorted using Venn diagrams (see Fig. 1A). The IUGR list (n = 893, 301 with q < 0.05) included all genes with a significant IUGR main effect but without a significant interaction. The second list (n = 906, 495 with q < 0.05) included all genes with a significant insulin clamp main effect but without a significant interaction. The third list (n = 1,433, none with q < 0.05) included all genes with a significant interaction. Morpheus (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus/) was used to generate heat maps using hierarchical clustering with Pearson correlations and average linkage methods. Separate heatmaps were generated for interaction gene subsets as described below. In Table 4, the unadjusted P value and adjusted P value (q value) following the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure are reported.

Fig. 1.

Effect of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp (insulin clamp) on fetal hepatic transcriptome. A: gene expression data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (4 experimental groups, n = 3 per group) resulting in groups of genes with a significant (P < 0.05) main effect for IUGR or clamp and those with a significant interaction (P < 0.05). The Venn diagram illustrates the groups of genes used for functional annotation. All genes with a significant interaction effect were grouped together (yellow circle). The remaining genes with significant main effect of IUGR or clamp were grouped together. B: genes with a significant main effect (P < 0.05) of IUGR and fold change >1.5 were loaded into a clustered heat map. C: genes with a significant main effect (P < 0.05) of clamp and fold change >1.5 were loaded into a clustered heat map. Genes with a significant IUGR × insulin clamp interaction were sorted into three categories based on biologically meaningful criteria using individual posttest as described in materials and methods. D and E: genes that were down- or upregulated only in the IUGR liver during the insulin clamp. F: genes resistant to insulin in the IUGR liver (IUGR + IR, yellow). In each heat map, genes that were downregulated or upregulated in are shown in blue or red, respectively. CON, control.

Table 4.

Top five genes with largest absolute fold change in groups of genes with significant effects from ANOVA

| Expression Relative to CON + Basal |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene Namea | Entrez ID |

P Value |

q Value | CON basal | CON clamp | IUGR basal | IUGR clamp | Fold Changeb | |

| IUGR main effect | ||||||||||

| PCK1 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 | 282855 | <0.0001 | 0.008 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 23.2 | 7.5 | 16.5 | up |

| ARG2 | Arginase 2 | 518752 | <0.0001 | 0.016 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 15.3 | 10.3 | 12.1 | up |

| GAST | Gastrin | 280800 | 0.004 | 0.072 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 3.0 | 23.0 | 9.8 | up |

| MUSTN1 | Musculoskeletal, embryonic nuclear protein 1 | 616088 | <0.0001 | 0.016 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 6.9 | 15.6 | 9.4 | up |

| PTPRD | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type D | 532751 | <0.0001 | 0.008 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 8.4 | down |

| Insulin clamp main effect | ||||||||||

| TNFAIP6 | TNF-α-induced protein 6 | 493710 | <0.0001 | 0.012 | 1.0 | 5.7 | 1.7 | 22.7 | 8.8 | up |

| FOLR3 | Folate receptor 3 | 516067 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 5.1 | 5.2 | up |

| LBP | Lipopolysaccharide binding protein | 512242 | 0.010 | 0.071 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 9.5 | 5.0 | up |

| TNFRSF12A | TNF receptor superfamily member 12A | 617439 | 0.002 | 0.030 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 14.8 | 4.9 | up |

| CD40 | CD40 molecule | 286849 | 0.003 | 0.040 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.3 | 8.7 | 4.4 | up |

| IUGR × insulin clamp interaction effect | ||||||||||

| SPP1 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | 281499 | 0.001 | 0.249 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 82.0 | 50.8 | up |

| PTX3 | Pentraxin 3 | 541148 | 0.008 | 0.349 | 1.0 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 110.5 | 48.8 | up |

| HP | Haptoglobin | 280692 | <0.0001 | 0.151 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 52.7 | 24.4 | up |

| ADAMTS4 | ADAM metallopeptidase thrombospondin motif 4 | 286806 | 0.006 | 0.335 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 42.6 | 22.6 | up |

| OLR1 | Oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor 1 | 281368 | 0.007 | 0.341 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 28.8 | 19.5 | up |

CON, control; DAVID, Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery; insulin clamp, hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp; INS, insulin; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

Gene name provided when Affymetrix probe ID matched a known gene with Entrez ID based in DAVID 6.8. If no match, only Affymetrix ID is listed.

Fold change is based on ANOVA main effect of IUGR or insulin (P < 0.05) or for the interaction genes, the fold change in IUGR + clamp relative to IUGR + basal.

The list of genes with significant interaction effects was further sorted into three biologically relevant categories using individual posttest comparisons (unadjusted P values). Genes were grouped as IUGR insulin-resistant genes (n = 51) if there was a relative fold change >1.5 with the insulin-clamp in CON livers (absolute fold change >1.5; CON + clamp vs. CON + basal) and no change with the insulin clamp in IUGR livers (absolute fold change <1.5; IUGR + clamp vs. IUGR + clamp). IUGR × insulin clamp down- (n = 784) or upregulated (n = 457) genes were grouped, respectively, as those with an absolute fold change >1.5 in IUGR + clamp versus IUGR + basal and either a fold change <1.5 in CON + clamp versus CON + basal or a 1.0 unit fold change value greater in the IUGR group versus CON group. One hundred and forty-one entities did not meet criteria for inclusion into one of these three groups and were not studied further.

Functional Annotation and Pathway Identification

The Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery Bioinformatic Resource (version 6.8) was used to update gene names and Entrez IDs for each gene and to perform functional annotation (23, 24). The direction of regulation (up or down) was considered within each gene list. Each gene list was queried to generate functional annotations based on enrichment for Gene Ontology (GO) terms/pathways for molecular function and biological process and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways using the Functional Annotation Clustering Tool. Default parameters were used for medium stringency except a minimum of four genes was required within a term. Clusters with an enrichment score >1.5 were considered significant, and only the top three are shown for each list of genes. Within the small list of IUGR insulin-resistant genes (n = 51), clustering was not used, and significant annotation terms were considered (P < 0.05).

1H-NMR Metabolomics Analyses

1H-NMR spectroscopy was performed to measure metabolites in liver samples from the same three fetuses per group used in the array analysis plus one additional sample for a total of four samples per group. Samples of powdered liver tissue (right lobe liver) were extracted using the perchloric acid method (45). Metabolite detection and quantification was performed at the University of Colorado Cancer Center Metabolomics Core using 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Hydrophilic (water soluble) and lipid fractions were profiled. MetaboAnalyst version 4.0 was used for data normalization and multivariate partial least squares discriminate analysis (PLS-DA). Metabolites with the highest variable importance in projection scores were used in the clustered heat map.

Gene and Protein Expression Validation Studies

For validation of gene expression by quantitative PCR, 4 to 11 samples per group (see figure legends) were used, including the 12 samples in the array experiment. RNA was extracted, and gene expression was measured as described (6, 47, 48) using primers for fatty acid synthase (FASN) and sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1c (SREBP1c) as reported (50). Primers for 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1 (HMGCS1), acetyl-Co-A carboxylase 1 (ACC1), WNT signaling pathway regulator (APC), arginase 2 (ARG2), AP-1 transcription factor subunit (JUN), c-MYC transcription factor (MYC), peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPARG), protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type D (PTPRD), serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 (SGK1), and tribbles pseudokinase 3 (TRIB3) are in Table 1. Results were normalized to S15 expression (47, 48). Whole cell protein lysates were prepared from liver tissue (left lobe) for Western immunoblotting using antibodies for phosphorylated and total forms of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR, S2448), ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K, S421/T424), ribosomal protein S6 (S6, S235/S236), eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1, T37/T46), eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2A (eIF2α, S51), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK, T172), and ERK (T202/Y204) using antibodies as previously described in fetal sheep liver and muscle samples (7, 48). Specificity of antibodies was verified by the presence of a single band at the expected molecular weight. Bands for phosphorylated and total forms of proteins were verified to be the same molecular weight when blots were aligned. For antibodies against phosphorylated proteins, specificity was further confirmed in optimization experiments by increased signal in biological samples (sheep liver, muscle, or isolated hepatocytes) stimulated with 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AMP mimetic), insulin, or amino acids. Samples were run on two blots (10 samples each plus a reference sample). Results were quantified on each blot, and data for the reference sample on both blots were determined similar. Hepatic triglycerides were measured on lipid extracted samples using the Infinity Triglyceride reagent as described (46).

Table 1.

Primer sequences for real-time PCR assays

| Symbol | Gene Name | Forward Primer (5′- to -3′) | Reverse Primer (5′- to -3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACC1 | Acetyl-Co-A carboxylase 1 | CGATGTCAACCTCCCTGCCGC | ATCGCCCCAGGGAGAGACCC |

| APC | APC, WNT signaling pathway regulator | AGCGGCAGAATGAAGGTCAA | CCTTCGAGGAGCAGAGTGTG |

| ARG2 | Arginase 2 | GCTCCAGCCACAGGAACCCC | TCCAGGGCCGAGAGCAACCC |

| HMGCR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase | TTGCTGGGCTCTTCACCATT | GCAGCAGGAAAAAGGGCAAA |

| HMGCS1 | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1 | GATCGAGTCCAGCTCTTGGG | AGGTCTGGCATTTCCTGTGG |

| JUN | Jun proto-oncogene, AP-1 transcription factor subunit | CCTTCTACGACGATGCCCTC | CAGGGTCATGCTCTGCTTCA |

| MYC | MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor | CCCCTGCCAAAAGGTCAGAA | CTTTAGGACCAACGGGCTGT |

| PPARG | peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma | GCGAGGGCGATCTTGACGGG | CCTGCAGGGGGCTGATGTGC |

| PTPRD | Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type D | GGCAGCGACTTGTGGAAATACCG | TGTGAGCTTTAGAGCTGGCTAGACG |

| S15 | Ribosomal protein S15 | ATCATTCTGCCCGAGATGGTG | CGGGCCGGCCATGCTTTACG |

| SGK1 | Serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 | ACCGTGGACTGGTGGTGCCT | TGGCTTCAGCTGGAGGGGCT |

| TRIB3 | Tribbles pseudokinase 3 | CCTCCCAAGGCAGCCCATGC | TGCTTCCGGCTGGGACACTCA |

Statistical Analyses

All other data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using the mixed procedure of SAS with fixed main effects of IUGR (CON vs. IUGR), insulin clamp (basal vs. insulin clamp), and the interaction. Data are presented as means ± SE, and significance is considered when P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Fetal Characteristics

CON and IUGR fetuses were studied under saline infusion (basal) or insulin clamp conditions at 0.9 gestation (Table 2) as previously reported (7, 47). The IUGR fetuses weighed 50% less relative to CON fetuses. Arterial oxygen, glucose, and insulin concentrations were lower, and lactate, cortisol, and norepinephrine concentrations were greater in IUGR compared with CON fetuses. During the insulin clamp, isoglycemia was maintained with exogenous glucose infusions, and insulin concentrations were increased >40-fold, by design, in CON + clamp and IUGR + clamp fetuses over 3 h (7, 47). Fetal arterial oxygen content decreased during the insulin clamp in both groups.

Table 2.

Fetal characteristics

| ANOVA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON + Basal | CON + Clamp | IUGR + Basal | IUGR + Clamp | IUGR | Clamp | INT | |

| Fetal sex (male/female/unknown) | 1:4:1 | 7:3:1 | 1:5:2 | 6:5:1 | |||

| Fetal age, days | 131 ± 0.6 | 133 ± 0.5 | 132 ± 0.8 | 133 ± 0.5 | |||

| Fetal weight, kg | 3.25 ± 0.13 | 3.53 ± 0.14 | 1.84 ± 0.20 | 2.01 ± 0.17 | <0.0001 | 0.31 | 0.42 |

| Fetal arterya | |||||||

| Blood oxygen content, mM | 3.06 ± 0.07 | 2.50 ± 0.22 | 1.39 ± 0.31 | 0.92 ± 0.11 | <0.0005 | <0.05 | 0.43 |

| Plasma glucose, mg/dl | 23.7 ± 3.6 | 18.1 ± 1.4 | 12.2 ± 1.7 | 15.1 ± 1.2 | <0.0005 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Plasma lactate, mM | 1.90 ± 0.05 | 2.74 ± 0.60 | 5.87 ± 2.08 | 11.02 ± 1.90 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.44 |

| Plasma insulin, ng/ml | 0.29 ± 0.10 | 15.68 ± 2.31 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 18.25 ± 3.62 | 0.88 | <0.001 | 0.94 |

| Plasma cortisol, ng/ml | 14.2 ± 2.8 | 11.8 ± 3.1 | 26.2 ± 8.2 | 83.1 ± 46.0 | 0.61 | 0.82 | 0.79 |

| Plasma norepinephrine, pg/ml | 351 ± 29 | 895 ± 202 | 1,370 ± 317 | 4,471 ± 2,737 | 0.64 | 0.78 | 0.88 |

Data are means ± SE; n = 6 CON + Basal, 11 CON + Clamp, 8 IUGR + Basal, and 12 IUGR + Clamp fetuses. CON, control; insulin clamp, hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; INT, interaction.

For fetal artery data, the mean values from all four samples during the final study period before necropsy are presented.

Fetal Hepatic Transcriptome

The fetal hepatic transcriptome was evaluated in CON and IUGR fetuses under basal or insulin clamp conditions. This allowed us to identify three sets of genes as shown in Fig. 1A that are regulated by IUGR, regulated by the insulin clamp, or have a differential response (interaction) during the insulin clamp in CON versus IUGR fetuses. The genes in these groups were used for functional annotation clustering where enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, and GO annotation terms (pathways) were clustered together when similar genes were present among the terms in the cluster (Table 3). The annotation terms (pathways), enrichment score, and number of genes shared among the pathways in each cluster are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Functional annotation pathway cluster analysis

| Clusters and Annotation Termsa | Validationb |

|---|---|

| IUGR downregulated clusters | |

| Cluster 1: cholesterol and lipid synthesis; enrichment = 4.9, count = 9 | |

| GO: isoprenoid biosynthetic process, cholesterol biosynthetic process KEGG: terpenoid backbone biosynthesis |

HMGCR, HMGCS1, lipids (NMR), Triglycerides, SREBP1C, |

| FASN, ACC1 | |

| Cluster 2: dehydrogenases, amino acid degradation; enrichment = 2.9, count = 11 | |

| KEGG: arginine and proline metabolism, tryptophan metabolism, histidine metabolism | Amino acids, metabolites (NMR) |

| Cluster 3: detoxification; enrichment = 2.2, count = 12 | |

| GO: glutathione transferase activity | IDH1, Glutathione, mitochondrial |

| KEGG: drug metabolism - cytochrome P450, metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450, glutathione metabolism, chemical carcinogenesis | intermediates (NMR) |

| IUGR upregulated clusters | |

| Cluster 1: glucose metabolism; enrichment = 3.4, count = 18 | |

| GO: glycolytic process KEGG: biosynthesis of amino acids, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, biosynthesis of antibiotics, carbon metabolism, fructose and mannose metabolism, central carbon metabolism in cancer |

ARG2, PCK1, G6PC, LDHA, PC, PFK1, PKLR (6, 47), glucose, lactate (NMR) |

| Cluster 2: regulatory and transcription factors; enrichment = 2.4, count = 37 | |

| GO: response to cytokine, positive regulation of cell differentiation, regulation of cell death, response to cAMP, response to radiation, transcription coactivator activity, cellular response to hormone stimulus, transcription factor binding, response to mechanical stimulus, regulation of cell cycle, RNA polymerase II core promoter proximal region sequence-specific DNA binding, response to drug, RNA polymerase II transcription factor activity, sequence-specific DNA binding | JUN, SGK1, TRIB3, PGC1A (47) |

| Cluster 3: cytokines, chemokines, innate immune response via TLR4 and NFκb; enrichment = 2.4, count = 39 | |

| GO: lipopolysaccharide-mediated signaling pathway | JUN |

| KEGG: salmonella infection, Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis), toll-like receptor signaling pathway, leishmaniasis, rheumatoid arthritis, toxoplasmosis, pertussis, malaria, tuberculosis, hepatitis B, measles | |

| Insulin clamp upregulated clusters | |

| Cluster 1: cholesterol and lipid synthesis; enrichment = 3.2, count = 15 | |

| GO: cholesterol biosynthetic process, isoprenoid biosynthetic process | HMGCR, HMGCS1 |

| KEGG: terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, biosynthesis of antibiotics | |

| Cluster 2: chemokines and innate immune response; enrichment = 2.9, count = 18 | |

| GO: inflammatory response | |

| KEGG: NF-κB signaling pathway, salmonella infection | |

| Cluster 3: amino acid stress and inflammation; enrichment = 1.6, count = 15 | |

| GO: cellular response to amino acid starvation | mTOR, eIF2α signaling |

| KEGG: influenza A, hepatitis C, measles | |

| Interaction: downregulated in IUGR during insulin clamp | |

| Cluster 1: dehydrogenases and amino acid catabolism; enrichment = 2.9, count = 21 | |

| KEGG: biosynthesis of antibiotics, carbon metabolism, biosynthesis of amino acids | ARG2, metabolites (NMR) |

| Cluster 2: lipid and amino acid degradation; enrichment = 2.3, count = 16 | |

| KEGG: valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation, fatty acid degradation, β-alanine metabolism, lysine degradation, tryptophan metabolism | Lipid, amino acid metabolites (NMR) |

| Cluster 3: insulin and AMPK signaling; enrichment = 1.5, count = 17 | |

| KEGG: insulin resistance, insulin signaling pathway, AMPK signaling pathway, Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | G6PC, GSK3B signaling (47), AMPK, ERK signaling, lipids, amino acids (NMR) |

| Interaction: upregulated in IUGR during insulin clamp | |

| Cluster 1: proteasome; enrichment = 5.4, count = 13 | |

| GO: threonine-type endopeptidase activity, ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | |

| KEGG: Proteasome | |

| Interaction: insulin resistant in IUGR | |

| No significant pathway clusters | |

| GO: cellular response to DNA damage stimulus, transcription regulatory region DNA binding, positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter, negative regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | APC, MYC, JUN, SGK1, PPARG |

For full gene names see Tables 1 and 4 or refer to the text. AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; GO, Gene Ontology; insulin clamp, hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance.

The GO and KEGG annotation terms that represent each cluster are listed and used to create a general name for each cluster. The enrichment score and number of genes in each cluster (count) are indicated.

The genes selected for validation within each cluster are listed. Genes that have been validated in previous publications are indicated with the supporting reference. In some clusters, additional genes, metabolites, or proteins with relevance to the pathway were selected for validation and are indicated with parentheses.

Genes differentially expressed in IUGR.

In the group of genes differentially expressed in the IUGR compared with CON fetal liver, there were 511 downregulated genes (57%; 408 unique genes based on Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery IDs) and 383 upregulated genes (43%; 295 unique genes; Fig. 1B). Based on the pathway cluster analysis, the genes that were downregulated in IUGR were related to cholesterol synthesis, dehydrogenase activity and amino acid degradation, and detoxification pathways (Table 3). The upregulated genes were enriched in pathways relating to glucose metabolism, regulatory and transcription factors, and activation of the innate immune response (Table 3). The top five genes most affected by IUGR with the largest absolute fold change in the IUGR fetal liver are shown in Table 4.

Genes regulated by the insulin clamp.

In the group of genes regulated during the insulin clamp in the fetal liver, there were 387 downregulated genes (43%; 289 unique genes) and 519 upregulated genes (57%; 408 unique genes; Fig. 1C). No significant enrichment for pathway clusters was found in the list of insulin clamp downregulated genes. The list of upregulated genes was enriched with pathways clusters associated with cholesterol and lipid synthesis, innate immune response, and amino acid stress and inflammation pathways (Table 3). The top five genes most affected with the largest absolute fold change during the insulin clamp in the fetal liver are shown in Table 4.

Genes differentially regulated by IUGR and the insulin clamp.

To interrogate biologically meaningful comparisons regarding the differential response to the insulin clamp in the liver of CON and IUGR fetuses, genes with a significant interaction (n = 1,433 total genes representing 1,115 unique genes) were filtered into three groups. This included subsets of genes that were down- (Fig. 1D) or upregulated (Fig. 1E) during the insulin clamp only in IUGR, respectively, and genes that were increased or decreased with the insulin clamp in the CON but not IUGR fetal liver supporting resistance to insulin action in IUGR (IUGR + IR; Fig. 1F).

We found that 87% of the genes in the interaction group were more responsive during the insulin clamp in the IUGR fetal liver with 55% downregulated (n = 784, Fig. 1D) and 32% upregulated (n = 457, Fig. 1E) in the IUGR + clamp versus IUGR + basal group but not the CON + clamp versus CON + basal group. This indicates a hyperresponsiveness to the insulin clamp that is present only in the IUGR but not CON fetal liver on the suppression and activation of gene expression. Functional annotation analysis was performed on the two subsets of genes that were down- or upregulated during the insulin-clamp only in IUGR (Table 3). Pathways that were downregulated in the IUGR fetal liver during the insulin clamp were associated with dehydrogenases and amino acid catabolism, lipid and amino acid degradation, and insulin and AMPK signaling pathways. Pathways that were upregulated in the IUGR fetal liver during the insulin clamp were associated with proteasome subunit activation. The top five genes with the largest absolute fold change in the IUGR + clamp relative to IUGR + basal fetal liver are shown in Table 4.

In the third subset of genes with an interaction effect, we found 51 genes (3.6%) that were increased or decreased with the insulin clamp in the CON but not IUGR fetal liver (Fig. 1F). These genes, like the gluconeogenic genes (47), demonstrate a pattern of expression whereby expression is not increased or decreased during the clamp in the IUGR fetal liver in contrast to the CON fetal liver. Thus, these genes may be candidate genes contributing to the resistance to suppression with insulin in IUGR fetal liver (IUGR + IR). Given the small number of genes in this group, no significant pathway clusters were identified. However, genes in this group were associated with GO terms relating to cell stress and transcriptional regulation (Table 3).

Validation Analysis

To validate the results from the microarray profiling experiments, we focused on the following pathways and targets based on their potential relationship with metabolism or insulin sensitivity in the IUGR fetal liver. The gene targets and/or related proteins and metabolites selected for validation within each pathway cluster are listed in Table 3 and their roles are further described in discussion.

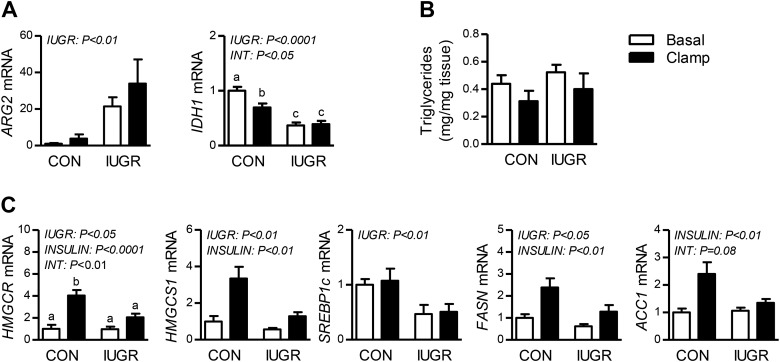

Glucose and mitochondrial metabolism.

We have previously shown that expression of PCK1, the gene with the largest fold change induction in IUGR (Table 4), was increased in IUGR and remained increased during the insulin clamp (47). We also showed that expression of other genes involved in glucose metabolism (Table 3), including G6PC, LDHA, PC, PFK1, and PKLR were increased in the IUGR fetal liver (5, 47). Here, we show that expression of ARG2, the mitochondrial isoform of arginase and gene with the second largest fold increase in the IUGR liver (Table 4), was increased >20-fold when confirmed by quantitative PCR (Fig. 2A). We also confirmed decreased expression of IDH1, a mitochondrial enzyme in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Regulation of metabolic genes and lipid synthesis by intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp (insulin clamp) conditions in fetal liver. A: expression of metabolic genes arginase 2 (ARG2) and IDH1 in control (CON) and IUGR fetal livers during basal or insulin conditions. B: fetal hepatic triglyceride content. C: expression of genes in lipid biosynthesis pathway measured in control and IUGR fetal livers during basal or insulin clamp conditions. Significant effects from two-way ANOVA are indicated. Means ± SE are shown for each group in saline (n = 5 CON, 9 IUGR) and insulin (n = 11 CON, 13 IUGR). ACC1, acetyl-Co-A carboxylase 1; FASN, fatty acid synthase; HMGCR, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase; HMGCS1, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1; SREBP1c, sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1c.

Cholesterol and lipid synthesis.

Cholesterol and lipid synthesis was the top downregulated pathway in the IUGR fetal liver and the top upregulated pathway during the insulin clamp. However, there were no differences in hepatic triglyceride content when measured biochemically (Fig. 2B). We next measured hepatic expression of key genes in cholesterol and lipid synthesis (Fig. 2C). Consistent with the array data, expression of HMGCR and HMGCS1, genes in cholesterol synthesis, was lower in the IUGR fetal liver. Hepatic expression of other lipogenic genes, SREBP1C and FASN, were decreased in IUGR yet ACC1 expression was unchanged. Expression of HMGCR, HMGCS1, FASN, and ACC1 increased during the insulin clamp in both CON and IUGR fetal livers supporting maintained insulin activation of these genes (Fig. 2C).

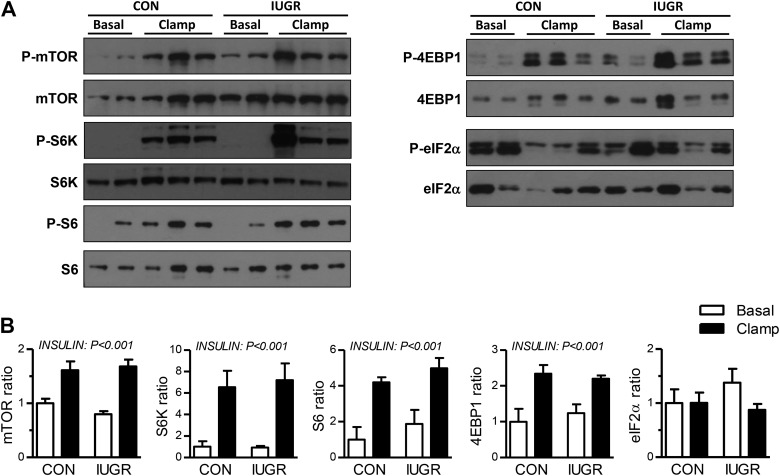

mRNA translation and protein synthesis.

Given the upregulation of genes associated with mRNA translation and amino acid stress during the insulin clamp and the established role of insulin in stimulating protein synthesis via mTORC1 (51), we measured signaling proteins involved in these pathways (51, 56). Under basal conditions, the expression and phosphorylation state of mTOR, S6K, S6, 4EBP1, and eIF2α was similar between CON and IUGR fetal livers (Fig. 3). In response to the insulin clamp, the phosphorylation state of mTOR, S6K, S6, and 4EBP1 proteins increased in CON and IUGR fetal livers (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Activation of proteins regulating protein synthesis pathway in the fetal liver in response to insulin clamp conditions. A: phosphorylated (p-) and total protein expression was measured by Western blotting in whole cell tissue lysates for mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (S2448), ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) (S421, T424), ribosomal protein S6 (S6) (S235/S236), 4EBP1 (T37/T46), and eIF2α (S51). Representative images are shown. B: results were quantified, and the ratio of phosphorylated to total protein was calculated. Means ± SE are shown for saline [n = 4 control (CON), 4 intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)] and insulin (n = 6 CON, 6 IUGR). Significant effects from two-way ANOVA are indicated. 4EBP1, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1; eIF2α, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2A; insulin clamp, hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp.

Fig. 4.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and ERK signaling pathways in the intrauterine growth-restricted (IUGR) fetus and in response to the hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp (insulin clamp). Phosphorylated (p-) and total protein expression for ERK (T202, Y204) and AMPK (T172) measured by Western blotting in whole cell tissue lysates. Representative images are shown. Results were quantified and ratio of phosphorylated to total protein was calculated. Means ± SE are shown for saline [n = 4 control (CON), 4 IUGR) and insulin (n = 6 CON, 6 IUGR]. Significant effects from two-way ANOVA are indicated.

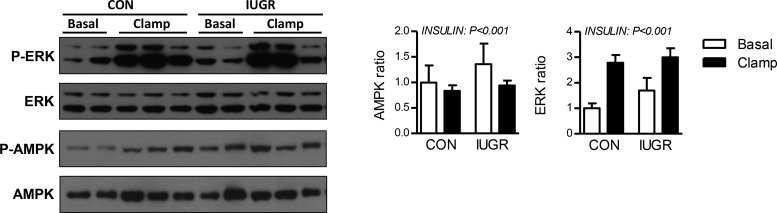

Insulin and AMPK signaling.

Pathways associated with insulin and AMPK signaling were identified in the downregulated set of genes in the IUGR liver during the insulin clamp (Table 3). Our previous studies showed increased phosphorylation of AKT and GSK3β proteins during the insulin clamp in both CON and IUGR fetal livers (47). Here, we extend these findings to ERK and AMPK activation. We found no difference between CON and IUGR fetal livers for the activation or ERK or AMPK (ratio of phosphorylated to total protein) under basal conditions (Fig. 4). During the insulin clamp, AMPK phosphorylation decreased and ERK phosphorylation increased by nearly twofold in both CON and IUGR fetal livers (Fig. 4).

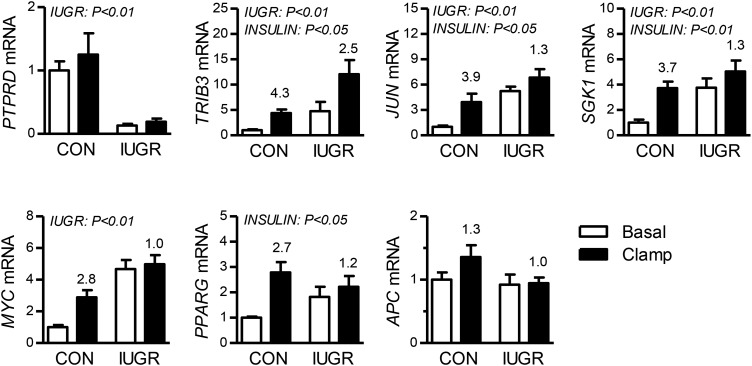

Candidate genes for activation of HGP and development of insulin resistance.

In the IUGR liver, we found upregulation of pathways with regulatory and transcription factors that included JUN, SGK1, and TRB3 (Fig. 6). PGC1A also was part of this cluster and is a gene we have previously shown to be increased in the IUGR fetal liver (47). Among the annotation terms in the subset of IUGR insulin-resistant genes, 12 genes were shared in common, including JUN, SGK1, MYC, APC, and PPARG, which we selected for validation based on putative roles in regulating insulin action [see later in discussion (12, 13, 17, 21, 25, 55)]. In addition, we measured PTPRD, the gene with the largest fold decrease in expression in the IUGR liver because of its function as a protein tyrosine phosphatase and association with insulin resistance (10, 37). Our results confirmed an 80% decrease in PTPRD expression and more than threefold increases in JUN, SGK1, TRB3, and MYC expression in the IUGR fetal liver (Fig. 5). The insulin clamp also increased expression of JUN, SGK1, TRB3, and PPARG. In contrast to the array results, no significant interaction (IUGR × insulin clamp) was found for JUN, SGK1, MYC, PPARG, APC, or IER2. However, the relative fold increase with the insulin clamp compared with basal was greater in the CON than in the IUGR fetal livers for JUN, SGK1, TRB3, MYC, and PPARG (Fig. 5). No differences were found for APC expression with IUGR or the insulin clamp.

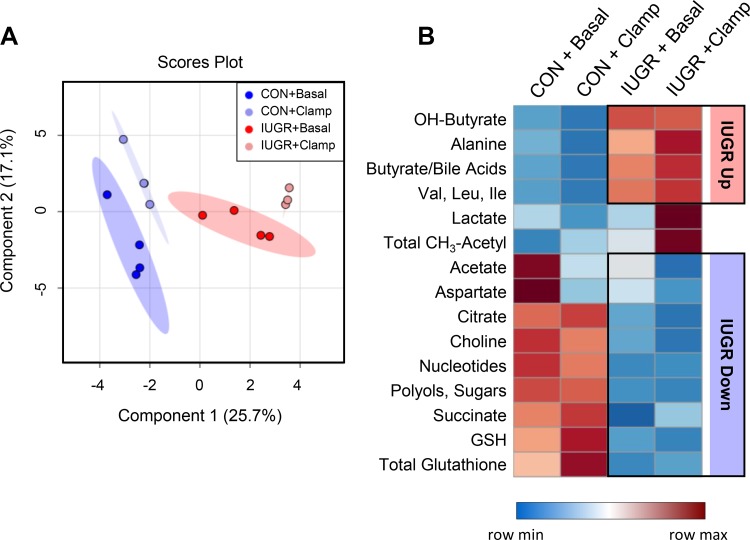

Fig. 6.

Effect of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and the hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp (insulin clamp) on fetal hepatic metabolites. Fetal liver samples were used for 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) profiling of hydrophilic metabolites (n = 4 per group). Partial least squares discriminate analysis (PLS-DA) was used to identify metabolites with changes in abundance that defined separation of samples between the groups, and the 2-dimensional blot is shown (A). Heat map of the 15 metabolites with the highest variable importance in projection score (VIP) scores between the groups (B). Each square is representative of the concentrations of that metabolite. Row values are normalized for each metabolitem and quantitative changes are color coded from blue (least) to red (greatest). Metabolite name and pathway category assignment is shown on left y-axis. CON, control; insulin clamp, hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp.

Fig. 5.

Candidate genes involved in regulating insulin sensitivity in intrauterine growth-restricted (IUGR) fetal liver. Expression of candidate genes for development of hepatic insulin resistance in IUGR are shown. The fold increase by insulin during the hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp (insulin clamp) within the control (CON) or IUGR group is indicated above the bars. Significant effects from two-way ANOVA are indicated. Means ± SE are shown for each group in saline (n = 5 CON, 9 IUGR) and insulin (n = 11 CON, 13 IUGR). APC, WNT signaling pathway regulator; JUN, AP-1 transcription factor subunit; MYC, c-MYC transcription factor; PPARG, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ; PTPRD, protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type D; SGK1, serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1; TRIB3, tribbles pseudokinase 3.

Fetal Hepatic Metabolites

We used 1H-NMR metabolomics to measure metabolite profiles in the CON and IUGR fetal liver under basal and insulin clamp conditions to determine the impact of IUGR on metabolic pathways beyond glucose metabolism and the differential response to insulin. Thirty-three water-soluble metabolites were identified (Table 5). PLS-DA showed distinct separation between CON and IUGR samples (Fig. 6A). The basal and insulin clamp samples clustered close within each CON and IUGR group, suggesting a lesser effect of the insulin clamp relative to IUGR. The 15 metabolites with the highest variable importance in projection scores from the PLS-DA are shown (Fig. 6B). The metabolites also were analyzed with univariate analysis (Table 5). Hepatic concentrations of alanine, branched chain amino acids (valine, leucine, and isoleucine), β-hydroxybutyrate, and butyrate + bile acids (features with overlapping peaks) were increased in IUGR livers (Fig. 6B; IUGR main effect, P < 0.05, Table 5). Nucleotide, total glutathione, and reduced glutathione concentrations were decreased in the IUGR fetal liver (Fig. 6B; P < 0.05, Table 5) suggesting decreased energy status and increased oxidative stress. Additionally, concentrations of acetate, citrate, and succinate, all mitochondrial intermediates, were decreased in the IUGR liver (Fig. 6B; P < 0.10, Table 5). The IUGR fetal liver also had lower concentrations of aspartate, choline, and polyols (Fig. 6B). Hepatic concentrations of lactate were higher during the insulin clamp in IUGR fetuses (Fig. 6B, Table 5), consistent with increased plasma concentrations (Table 2). The abundance of all metabolites with CH3-acetyl groups was increased during the insulin clamp in IUGR liver (Fig. 6B, Table 5). No differences in total lipid content, cholesterol, or triglycerides were found between CON and IUGR fetal livers or with the insulin clamp, yet monounsaturated fatty acid levels were decreased in IUGR compared with CON fetal livers (P < 0.05, Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of IUGR and the insulin clamp on metabolites in the fetal liver

| ANOVA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite, mmol/g tissue | CON + Basal | CON + Clamp | IUGR + Basal | IUGR + Clamp | IUGR | Clamp | INT |

| Carbohydrates | |||||||

| Glucose | 7.1 ± 2.0 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 0.84 | 0.02 | 0.73 |

| Glycogen | 5.6 ± 1.0 | 8.7 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 0.02 | 0.85 | 0.01 |

| Lactate | 10.9 ± 1.3 | 8.6 ± 0.3 | 12.1 ± 1.4 | 15.4 ± 2.2 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.07 |

| Polyols, sugars | 118.5 ± 8.9 | 112.2 ± 5.6 | 110.6 ± 11.0 | 84.8 ± 7.7 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.27 |

| Amino acids | |||||||

| Alanine | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 1.0 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.42 |

| Glutamine | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.15 |

| Glutamate | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.17 |

| Valine, leucine, isoleucine | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 6.3 ± 1.4 | 5.1 ± 1.3 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.77 |

| Aromatic amino acids | 10.8 ± 0.9 | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 6.9 ± 1.5 | 10.4 ± 3.6 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.24 |

| Phenylalanine | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.82 |

| Tryptophan | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.07 |

| Taurine | 10.9 ± 0.6 | 8.9 ± 2.0 | 11.6 ± 4.1 | 6.7 ± 1.0 | 0.75 | 0.18 | 0.55 |

| Aspartate | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.40 |

| Methionine | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Tyrosine | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.74 |

| Lysine, arginine | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 0.83 | 0.48 | 0.14 |

| Mitochondrial intermediates | |||||||

| Acetate | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.74 |

| Citrate | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 0.57 |

| Succinate | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.75 |

| N-Acetylglutamate | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.13 | 0.86 | 0.84 |

| Energy status, cell stress | |||||||

| Adenine, adenosine | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 0.01 | 0.84 | 0.50 |

| Nucleotides | 9.6 ± 0.8 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.94 |

| Total glutathione | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.02 |

| GSH | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.15 |

| GSSG* | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.57 |

| GSSG/GSH ratio* | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.84 |

| Creatine, phosphocreatine | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.33 |

| β-Hydroxybutyrate | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.69 |

| Butyrate, bile acids | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 7.2 ± 2.5 | 6.4 ± 2.5 | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.95 |

| Other water-soluble metabolites | |||||||

| Total CH3-acetyl | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 8.4 ± 0.5 | 10.6 ± 1.5 | 10.1 ± 1.5 | 0.07 | 0.98 | 0.70 |

| Betaine | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Choline | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.69 |

| Glycerophosphocholine | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.16 |

| Lipid metabolites | |||||||

| Triglycerides | 40.8 ± 1.9 | 44.2 ± 4.1 | 40.0 ± 2.7 | 40.3 ± 3.9 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.64 |

| Cholesterol | 29.0 ± 0.8 | 29.2 ± 1.4 | 26.3 ± 0.6 | 28.2 ± 2.9 | 0.30 | 0.55 | 0.61 |

| MUFA | 11.1 ± 2.0 | 15.3 ± 1.7 | 10.4 ± 1.4 | 9.0 ± 1.0 | <0.05 | 0.39 | 0.10 |

| PUFA | 105 ± 12 | 115 ± 15 | 98 ± 14 | 80 ± 7 | 0.11 | 0.73 | 0.28 |

| PUFA/MUFA | 9.8 ± 0.8 | 7.5 ± 0.5 | 9.5 ± 0.6 | 9.3 ± 1.3 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 0.23 |

| Sphingomyelin | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.87 |

| Glycerol phospholipid | 65.3 ± 3.0 | 71.5 ± 6.2 | 59.7 ± 3.4 | 63.3 ± 7.1 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.80 |

| Phosphatidylserine | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 0.59 | 0.99 | <0.05 |

| Phosphatidylcholine | 30.1 ± 1.2 | 30.8 ± 2.5 | 28.9 ± 1.3 | 30.7 ± 3.7 | 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.82 |

| Phosphatidylinositol | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 0.69 | 0.21 | 0.45 |

| Total cholines | 119 ± 22 | 145 ± 9 | 133 ± 8 | 145 ± 16 | 0.66 | 0.23 | 0.66 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine | 22.7 ± 1.8 | 21.4 ± 0.9 | 20.0 ± 1.6 | 20.1 ± 3.0 | 0.33 | 0.77 | 0.76 |

| Total fatty acids | 165 ± 7 | 161 ± 14 | 148 ± 12 | 152 ± 17 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 0.78 |

| Total lipids (CH2n) | 1,606 ± 41 | 1,637 ± 115 | 1,461 ± 105 | 1,649 ± 196 | 0.61 | 0.40 | 0.55 |

| Total lipids | 390 ± 12 | 382 ± 26 | 350 ± 14 | 389 ± 42 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.40 |

Values are means ± SE. Metabolites measured in n = 4 liver samples per group. CONT, control; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acid; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

GSSG was calculated by subtracting GSH from total glutathione. The ratio of GSSG/GSH was calculated.

DISCUSSION

Our transcriptomic analyses and validation approaches identified novel genes and pathways that were affected by IUGR and the insulin clamp in the fetal liver. We used a global approach integrating transcriptomics and metabolomics to identify mechanisms for the early activation of HGP and resistance to suppression with insulin in the IUGR fetus. As such, we have focused our discussion on targets and pathways that are relevant to these outcomes. We found that in addition to activation of HGP (47), with PCK1 being the most upregulated gene, the IUGR fetal liver has an upregulation of other genes involved in glucose metabolism and downregulation of genes associated with cholesterol and lipid synthesis and amino acid degradation. The profile of metabolites in the IUGR fetal liver supports increased amino acid catabolism, decreased mitochondria activity and energy state, and increased cell stress. Collectively, these pathways and metabolites may reflect fetal hepatic adaptations that support HGP. Interestingly, in contrast to the inability of insulin to suppress gluconeogenic gene expression in the IUGR fetal liver (47), we found that most pathways within the IUGR fetal liver were responsive during the insulin clamp, including the expression of lipid synthesis genes and activation of signaling proteins involved in protein synthesis. Furthermore, there were many genes that were up- or downregulated during the insulin clamp only in the IUGR liver, suggesting a hyperresponsiveness to insulin that was unique to the IUGR condition. We also identified new molecular targets that may contribute to the development of resistance to insulin suppression of HGP in the IUGR fetal liver.

Our results complement our previous work and support a role for pathways linking FOXO1 with resistance to insulin suppression of HGP in the IUGR fetal liver. We have previously shown that nuclear localization of phosphorylated FOXO1 (T24 site) is increased in the IUGR fetal liver under basal conditions and in the presence of insulin during the clamp (47). Our pathway analysis identified SGK1, JUN, and MYC as new molecular regulatory factors with similar patterns of expression that are relevant to FOXO1 phosphorylation and increased PCK1 expression in the IUGR liver. First, all are increased under basal conditions and either not induced further (i.e., SGK1, JUN, MYC, FOXO1) or suppressed (i.e., PCK1) during the insulin clamp in the IUGR fetal liver. Second, JUN is an early response gene and transcription factor that is a target of the upstream kinase JNK. Importantly, we have shown that protein expression and phosphorylation state of JNK is increased in the IUGR fetal liver during the insulin clamp (47). Like AKT, the SGK1 protein is an AGC serine/threonine kinase and can phosphorylate FOXO1 at sites that cause inactivation (21). However, the function of increased SGK1 in the IUGR fetal liver is not fully clear given that FOXO1 activation is increased (47). Importantly, other studies have linked JNK to FOXO1 activation and AKT and SGK1 to FOXO1 inactivation via phosphorylation at different regulatory sites and thus support a role for these factors in regulating insulin action (12, 13, 17, 21, 25, 55). Moreover, upregulation and enrichment in the FOXO1 pathway also were found in the IUGR rat liver (4). The transcription factor c-MYC, encoded by the MYC gene, is a signaling molecule that receives inputs from cytokine and growth factor pathways and activates transcription of numerous genes (18). In addition, we confirmed increased TRB3 and decreased PTPRD expression in the IUGR liver. These genes encode proteins with signaling roles linked to insulin action (10, 33, 34, 37), yet their role in the IUGR condition is not clear. Collectively, we speculate that all these regulatory factors could have roles in the early activation of HGP and resistance to insulin suppression of HGP.

There was a hyperresponsiveness during the insulin clamp in the IUGR liver as evidenced by the up- or downregulation of numerous genes and pathways that did not change during the insulin clamp in the CON fetal liver. These genes were associated with pathways involving decreased lipid and amino acid degradation, decreased insulin and AMPK signaling, and increased proteasome activation. The IUGR liver also had an upregulation of pathways associated with cytokines and activation of the innate immune response. Together, these observations suggest a potential priming of immune and stress responses in the IUGR fetal liver that were only activated during the insulin clamp and subsequently resulted in the hyper-response at the transcriptomics level. However, we found no increase in the activation proteins relating to cell stress, including AMPK, ERK, or eIF2α, between CON and IUGR livers, consistent with our data in another cohort of IUGR fetuses (48). We speculate that exposure to the adverse intrauterine conditions during IUGR produces unique adaptive strategies for survival combined with an underlying potential proinflammatory state and vulnerability to metabolic stressors in the fetal liver (9), such as the experimental insulin clamp in our study. Additional studies are needed to test the effect of IUGR on the development of inflammation and other cell and oxidative stress pathways in the fetal liver.

Our results identified hepatic metabolic adaptations in the IUGR fetal liver with coordinated responses in the supply of carbon and energy substrates that may support HGP. In the IUGR liver, we found an upregulation of genes for glucose metabolism (gluconeogenesis and glycolysis), lactate production, and amino acid synthesis. There was a downregulation of genes associated with amino acid degradation, dehydrogenase activity, and detoxification pathways. Hepatic concentrations of lactate, alanine, and branched chain amino acids measured by 1H-NMR were increased in the IUGR fetus. In context with our prior studies, we propose that the IUGR liver has increased intrahepatic lactate concentrations because of increased lactate production (LDHA) and incomplete glucose oxidation (PDK4) (6). Furthermore, increased PC favors the conversion of pyruvate into oxaloacetate, the substrate for PCK1. Studies in a rat IUGR model support limited pyruvate oxidation in association with increased HGP (43). We speculate that glucogenic substrates, including amino acids and lactate, are used to fuel HGP in the IUGR fetus. Indeed, we have shown that increased amino acid supply can potentiate fetal HGP (5, 22). Increased hepatic amino acid concentrations and related metabolites also are consistent with downregulation of amino acid degradation pathways (Table 3). Increased ARG2 may function to increase ornithine and urea production as a result of increased amino acid catabolism and thus may be indirectly linked with hepatic glucose metabolism (Table 3). Alternately, increased ARG2 will decrease arginine availability for nitric oxide synthesis. Furthermore, decreased glutathione levels support the downregulation of detoxification pathways and glutathione metabolism in the IUGR fetal liver (Table 3). Hepatic concentrations of nucleotides, acetate, citrate, and succinate were decreased, suggesting decreased mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and lower hepatic energy state in the IUGR fetal liver, consistent with other studies in IUGR rat fetuses (27, 40). However, HGP is an energy-consuming pathway and is linked with lipid oxidation, which supplies energy and cofactors in the adult and neonate (16). Thus, we speculate that amino acid oxidation in the IUGR fetus may supply energy and cofactors for gluconeogenesis, given the low reliance of the ovine fetus on lipid oxidation (16). Further studies measuring fetal hepatic flux are needed to address these mechanisms.

In addition to inhibiting HGP, insulin activates anabolic pathways in the adult liver, including protein and lipid synthesis. Our results suggest pathway-specific resistance to insulin in the IUGR fetus whereby HGP and gluconeogenic gene expression are resistant to suppression with insulin during the clamp (4), yet the IUGR fetal liver responds robustly to insulin on a global transcriptomics level and specifically on lipogenic gene activation and protein synthesis signaling pathways. The inability of insulin to suppress HGP is a critical hallmark in the development of T2DM (31). There also is a paradox in adults with T2DM whereby insulin fails to suppress HGP, yet lipid synthesis and steatosis, both insulin sensitive processes, are increased. This concept was been referred to as pathway-specific (selective) hepatic insulin resistance (8, 30). The IUGR fetal liver did respond with increased protein synthesis pathways during the insulin clamp; however, the lipid component of this phenotype is not fully recapitulated. Specifically, there is no increase in lipid content, decreased SREBP1C and FASN, and no change in ACC1 in the IUGR fetal liver. Decreased expression of lipogenic genes also has been reported in the late gestation fetal rat IUGR liver (4, 14, 28). This is not surprising given low nutrient supply in IUGR and low reliance on lipids as a fuel for oxidative metabolism in the ovine fetus. However, after birth, human IUGR offspring are more susceptible to development of hepatic steatosis (1, 38). Recent studies also have shown insulin-independent mechanisms for hepatic lipid accumulation that include substrate flux and delivery of preformed fatty acids to the liver (41, 42, 44, 52). Although our data did not demonstrate an upregulation of lipogenic capacity or increased response to insulin on lipid synthesis in the IUGR relative to CON fetal liver, it is possible that in utero exposures in the liver prime the pathway for lipid accumulation when substrate flux increases postnatally.

We measured proteins in the mRNA translation and protein synthesis pathway for two reasons. First, we found an upregulated cluster of annotation terms associated with amino acid signaling in response to the insulin clamp in the fetal liver, prompting investigation of insulin action on protein synthesis via the mTOR pathway (39). Second, decreased hepatic mRNA translation has been found in a fetal rat IUGR model (4). However, our results demonstrate no difference in basal fetal hepatic translation capacity based on expression of proteins in the mTOR pathway in the IUGR fetal sheep liver and indicate a normal insulin-mediated increase in phosphorylation of key proteins and gene expression. This may reflect the chronic nature of placental insufficiency in our sheep model, which progresses over gestation and may allow for more adaptive responses to develop in the liver (48) in contrast to the acute stress of maternal fasting in the rat that decreases fetal liver weight within 48 h (48).

A unique strength in our study is the use of samples obtained during steady-state insulin clamp conditions in the fetus from a sheep model during a developmental period in late gestation when metabolic pathways are maturing in preparation for birth (16, 36). We chose a maximal dose of insulin for testing its effect on suppression of HGP and glucose utilization in the fetus (20, 47). The small effect of the insulin clamp on metabolite concentrations may reflect this short 3-h protocol, although the robust response during the insulin clamp at the transcriptome level suggests a unique capacity of the IUGR fetus to upregulate pathways via FOXO1 or downstream of ERK and AKT signaling. Although mechanistically interesting in terms of insulin action, the hyper-responsive condition could be secondary to increased norepinephrine or decreased oxygen and reflect metabolic stress during the insulin clamp (47). Further studies are needed to elucidate the effect of these conditions on fetal insulin action.

Perspectives and Significance

IUGR fetuses adapt to an adverse intrauterine milieu by optimizing the use of reduced supplies of nutrient (glucose and amino acids) and oxygen. We identified new pathways and mechanisms that the IUGR fetal liver has developed to cope with the adverse intrauterine environment that such deficiencies produce. Importantly, our data support a novel concept whereby hepatic insulin resistance may be limited to HGP in the IUGR fetal liver as numerous other genes and pathways, including lipid and protein synthesis, were activated during the insulin clamp. We also identified new molecular targets that may be responsible for mediating this differential insulin sensitivity in utero. This new information is important in understanding the metabolic consequences of IUGR on hepatic function and increased predisposition of these offspring to insulin resistance and metabolic disease across their lifespan.

GRANTS

Research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NIH-R01-DK108910 (to S. Wesolowski), pilot grant awards to S. Wesolowski from the University of Colorado Center for Women’s Health Research, and University of Colorado Nutrition Obesity Research Center Grants NIH-P30-DK048520, NIH-T32-HD007186 (to A. Jones, trainee; W. Hay, PI/PD), NIH-K12-HD068372 (to W. Hay, PD), NIH-R01-DK088139 and R01-HD093701 (to P. Rozance), and NIH-P30-CA046934 (to N. Serkova).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.R.W. conceived and designed research; A.K.J., N.J.S., and S.R.W. performed experiments; A.K.J. and S.R.W. analyzed data; L.D.B., P.J.R., W.W.H., J.E.F., and S.R.W. interpreted results of experiments; S.R.W. prepared figures; S.R.W. drafted manuscript; A.K.J., L.D.B., P.J.R., N.J.S., W.W.H., J.E.F., and S.R.W. edited and revised manuscript; S.R.W. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alisi A, Panera N, Agostoni C, Nobili V. Intrauterine growth retardation and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. Int J Endocrinol 2011: 269853, 2011. doi: 10.1155/2011/269853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 57: 289–300, 1995. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berends LM, Ozanne SE. Early determinants of type-2 diabetes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 26: 569–580, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boylan JM, Sanders JA, Gruppuso PA. Regulation of fetal liver growth in a model of diet restriction in the pregnant rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311: R478–R488, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00138.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown LD, Kohn JR, Rozance PJ, Hay WW JR, Wesolowski SR. Exogenous amino acids suppress glucose oxidation and potentiate hepatic glucose production in late gestation fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 312: R654–R663, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00502.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown LD, Rozance PJ, Bruce JL, Friedman JE, Hay WW JR, Wesolowski SR. Limited capacity for glucose oxidation in fetal sheep with intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309: R920–R928, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00197.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown LD, Rozance PJ, Thorn SR, Friedman JE, Hay WW JR. Acute supplementation of amino acids increases net protein accretion in IUGR fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 303: E352–E364, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00059.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Selective versus total insulin resistance: a pathogenic paradox. Cell Metab 7: 95–96, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton GJ, Fowden AL, Thornburg KL. Placental origins of chronic disease. Physiol Rev 96: 1509–1565, 2016. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YT, Lin WD, Liao WL, Lin YJ, Chang JG, Tsai FJ. PTPRD silencing by DNA hypermethylation decreases insulin receptor signaling and leads to type 2 diabetes. Oncotarget 6: 12997–13005, 2015. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Blasio MJ, Gatford KL, McMillen IC, Robinson JS, Owens JA. Placental restriction of fetal growth increases insulin action, growth, and adiposity in the young lamb. Endocrinology 148: 1350–1358, 2007. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Cristofano A. SGK1: The dark side of PI3K signaling. Curr Top Dev Biol 123: 49–71, 2017. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eijkelenboom A, Burgering BM. FOXOs: signalling integrators for homeostasis maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14: 83–97, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nrm3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freije WA, Thamotharan S, Lee R, Shin BC, Devaskar SU. The hepatic transcriptome of young suckling and aging intrauterine growth restricted male rats. J Cell Biochem 116: 566–579, 2015. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gentili S, Morrison JL, McMillen IC. Intrauterine growth restriction and differential patterns of hepatic growth and expression of IGF1, PCK2, and HSDL1 mRNA in the sheep fetus in late gestation. Biol Reprod 80: 1121–1127, 2009. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girard J. Metabolic adaptations to change of nutrition at birth. Biol Neonate 58, Suppl 1: 3–15, 1990. doi: 10.1159/000243294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haeusler RA, McGraw TE, Accili D. Biochemical and cellular properties of insulin receptor signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19: 31–44, 2018. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haikala HM, Anttila JM, Klefström J. MYC and AMPK-save energy or die! Front Cell Dev Biol 5: 38, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2017.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hales CN, Barker DJ. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Br Med Bull 60: 5–20, 2001. doi: 10.1093/bmb/60.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hay WW JR, Meznarich HK, DiGiacomo JE, Hirst K, Zerbe G. Effects of insulin and glucose concentrations on glucose utilization in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res 23: 381–387, 1988. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198804000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedrick SM, Hess Michelini R, Doedens AL, Goldrath AW, Stone EL. FOXO transcription factors throughout T cell biology. Nat Rev Immunol 12: 649–661, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nri3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houin SS, Rozance PJ, Brown LD, Hay WW JR, Wilkening RB, Thorn SR. Coordinated changes in hepatic amino acid metabolism and endocrine signals support hepatic glucose production during fetal hypoglycemia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 308: E306–E314, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00396.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 1–13, 2009. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4: 44–57, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang H, Tindall DJ. Dynamic FoxO transcription factors. J Cell Sci 120: 2479–2487, 2007. doi: 10.1242/jcs.001222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG; NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group . Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lane RH, Flozak AS, Ogata ES, Bell GI, Simmons RA. Altered hepatic gene expression of enzymes involved in energy metabolism in the growth-retarded fetal rat. Pediatr Res 39: 390–394, 1996. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane RH, Kelley DE, Gruetzmacher EM, Devaskar SU. Uteroplacental insufficiency alters hepatic fatty acid-metabolizing enzymes in juvenile and adult rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280: R183–R190, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.1.R183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane RH, MacLennan NK, Hsu JL, Janke SM, Pham TD. Increased hepatic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 gene expression in a rat model of intrauterine growth retardation and subsequent insulin resistance. Endocrinology 143: 2486–2490, 2002. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.7.8898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Bifurcation of insulin signaling pathway in rat liver: mTORC1 required for stimulation of lipogenesis, but not inhibition of gluconeogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 3441–3446, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914798107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Smith D, Hay WW JR. Increased insulin sensitivity and maintenance of glucose utilization rates in fetal sheep with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1716–E1725, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00459.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin-Gronert MS, Ozanne SE. Experimental IUGR and later diabetes. J Intern Med 261: 437–452, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsumoto M, Han S, Kitamura T, Accili D. Dual role of transcription factor FoxO1 in controlling hepatic insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest 116: 2464–2472, 2006. doi: 10.1172/JCI27047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsushima R, Harada N, Webster NJ, Tsutsumi YM, Nakaya Y. Effect of TRB3 on insulin and nutrient-stimulated hepatic p70 S6 kinase activity. J Biol Chem 281: 29719–29729, 2006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMillen IC, Robinson JS. Developmental origins of the metabolic syndrome: prediction, plasticity, and programming. Physiol Rev 85: 571–633, 2005. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00053.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrison JL, Berry MJ, Botting KJ, Darby JRT, Frasch MG, Gatford KL, Giussani DA, Gray CL, Harding R, Herrera EA, Kemp MW, Lock MC, McMillen IC, Moss TJ, Musk GC, Oliver MH, Regnault TRH, Roberts CT, Soo JY, Tellam RL. Improving pregnancy outcomes in humans through studies in sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 315: R1123–R1153, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00391.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakajima S, Tanaka H, Sawada K, Hayashi H, Hasebe T, Abe M, Hasebe C, Fujiya M, Okumura T. Polymorphism of receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase delta gene in the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 33: 283–290, 2018. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newton KP, Feldman HS, Chambers CD, Wilson L, Behling C, Clark JM, Molleston JP, Chalasani N, Sanyal AJ, Fishbein MH, Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB, Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN) . Low and high birth weights are risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. J Pediatr 187: 141–146.e1, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Brien RM, Granner DK. Regulation of gene expression by insulin. Physiol Rev 76: 1109–1161, 1996. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.4.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogata ES, Swanson SL, Collins JW JR, Finley SL. Intrauterine growth retardation: altered hepatic energy and redox states in the fetal rat. Pediatr Res 27: 56–63, 1990. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199001000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osório J. Diabetes: hepatic lipogenesis independent of insulin in type 2 diabetes mellitus--a paradox clarified. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11: 130, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Otero YF, Stafford JM, McGuinness OP. Pathway-selective insulin resistance and metabolic disease: the importance of nutrient flux. J Biol Chem 289: 20462–20469, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.576355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterside IE, Selak MA, Simmons RA. Impaired oxidative phosphorylation in hepatic mitochondria in growth-retarded rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 285: E1258–E1266, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00437.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samuel VT, Shulman GI. The pathogenesis of insulin resistance: integrating signaling pathways and substrate flux. J Clin Invest 126: 12–22, 2016. doi: 10.1172/JCI77812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Serkova NJ, Jackman M, Brown JL, Liu T, Hirose R, Roberts JP, Maher JJ, Niemann CU. Metabolic profiling of livers and blood from obese Zucker rats. J Hepatol 44: 956–962, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thorn SR, Baquero KC, Newsom SA, El Kasmi KC, Bergman BC, Shulman GI, Grove KL, Friedman JE. Early life exposure to maternal insulin resistance has persistent effects on hepatic NAFLD in juvenile nonhuman primates. Diabetes 63: 2702–2713, 2014. doi: 10.2337/db14-0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thorn SR, Brown LD, Rozance PJ, Hay WW JR, Friedman JE. Increased hepatic glucose production in fetal sheep with intrauterine growth restriction is not suppressed by insulin. Diabetes 62: 65–73, 2013. doi: 10.2337/db11-1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thorn SR, Regnault TR, Brown LD, Rozance PJ, Keng J, Roper M, Wilkening RB, Hay WW JR, Friedman JE. Intrauterine growth restriction increases fetal hepatic gluconeogenic capacity and reduces messenger ribonucleic acid translation initiation and nutrient sensing in fetal liver and skeletal muscle. Endocrinology 150: 3021–3030, 2009. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thorn SR, Rozance PJ, Brown LD, Hay WW JR. The intrauterine growth restriction phenotype: fetal adaptations and potential implications for later life insulin resistance and diabetes. Semin Reprod Med 29: 225–236, 2011. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]