Significance

In a quantum spin liquid, the spins remain disordered down to zero temperature, and yet, it displays topological order that is stable against local perturbations. The Kitaev model with anisotropic interactions on the bonds of a honeycomb lattice is a paradigmatic model for a quantum spin liquid. We explore the effects of a magnetic field and discover an intermediate gapless spin liquid sandwiched between the known gapped Kitaev spin liquid and a polarized phase. We show that the gapless spin liquid harbors fractionalized neutral fermionic excitations, dubbed spinons, that remarkably form a Fermi surface in a charge insulator.

Keywords: quantum spin liquid, fractionalization, Kitaev model, spinon

Abstract

The Kitaev model with an applied magnetic field in the direction shows two transitions: from a nonabelian gapped quantum spin liquid (QSL) to a gapless QSL at and a second transition at a higher field to a gapped partially polarized phase, where is the strength of the Kitaev exchange interaction. We identify the intermediate phase to be a gapless U(1) QSL and determine the spin structure function and the Fermi surface of the gapless spinons using the density matrix renormalization group (DMRG) method for large honeycomb clusters. Further calculations of static spin-spin correlations, magnetization, spin susceptibility, and finite temperature-specific heat and entropy corroborate the gapped and gapless nature of the different field-dependent phases. In the intermediate phase, the spin-spin correlations decay as a power law with distance, indicative of a gapless phase.

The inspired exact solution of the Kitaev model on a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice with bond-dependent spin exchange interaction (1) (Eq. 1) has emerged as a paradigmatic model for quantum spin liquids (QSLs). For equal bond interactions (), the ground state of the Kitaev model is known to be a topologically nontrivial gapless QSL with fractionalized excitations. The multiple ground-state degeneracy reflects the topology of the lattice manifold (twofold degeneracy on a cylinder and fourfold degeneracy on a torus). The promise of using fractionalized excitations for applications in robust quantum computing (1–5) has led to considerable excitement and activity in the field from diverse directions, all of the way from fundamental developments to applications. On breaking time-reversal symmetry (for example, by applying a magnetic field), the exact solvability of the Kitaev model is lost, but perturbatively, it can be shown that the Kitaev gapless QSL becomes a gapped QSL phase with nonabelian anyonic excitations (1).

To realize the exotic properties of the Kitaev model, there has been keen interest to discover Kitaev physics in materials. To this end, Mott insulators with magnetic frustration and large spin-orbit coupling have been proposed (6), leading to the discovery of and (A = Na, Li). These are candidate QSL materials with the desired honeycomb geometry. Although given additional interactions beyond the Kitaev interaction in materials, there is still controversy about the regimes where Kitaev physics can be accessed (7–12). Additionally, triangular and Kagome lattice with spin frustration has also been proposed as a candidate for a QSL (13–19). In this context, organics, such as -(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2 (CN)3 (20) and EtMe3Sb[Pd(dmit)2]2 (21), the transition metal dichalcogenides 1T- (19), and a large family of rare earth dichalcogenides (A = alkali or monovalent ions, Re = rare earth, X = O, S, Se) (22) have been explored. Remarkably, recent NMR and thermal Hall conductivity experiments on demonstrate that one can drive the magnetically ordered phase into a QSL phase using an external magnetic field (23, 24). To this end, various numerical tools were used to explore the possible QSL phases in the models relevant to candidate honeycomb materials with an external magnetic field (25–29).

In this article, we theoretically address the following question: what is the fate of the Kitaev QSL with increasing magnetic field (Eq. 1) beyond the perturbative limit? Previous studies, using a variety of numerical methods (30–33), have pushed the Kitaev model solution to larger magnetic fields outside the perturbative regime. At high magnetic fields, one would expect a polarized phase. What is surprising is the discovery of an intermediate phase sandwiched between the gapped QSL at low fields and the polarized phase at high fields when a uniform magnetic field is applied along the [111] direction (Fig. 1C). The main question that we focus on is as follows: what is the nature of this intermediate phase? A study based on exact diagonalization on small clusters claims to get an intermediate QSL phase with a stable spinon Fermi surface (SFS) (30). An independent analysis based on the central charge and symmetry arguments also deduce an SFS (34, 35). In this article, we present exact calculations of the spin structure factor on large systems and reconstruct the SFS in the intermediate phase, details of which are distinct from other recent proposals. These are the primary significant results of this work.

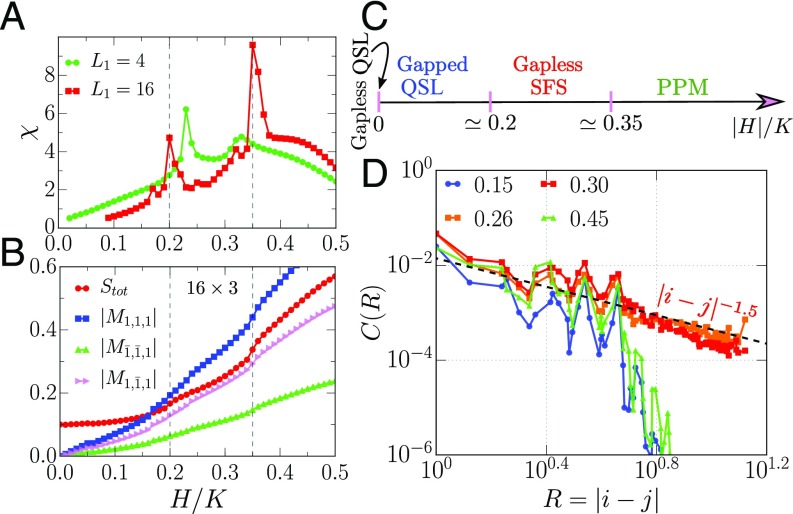

Fig. 1.

(A) Spin susceptibility () for and (B) different measures of magnetization as a function of magnetic field strength () for . The vertical dashed lines show critical magnetic fields where phase transitions occur. (C) Corresponding phase diagram that shows transitions from gapless QSL to gapped QSL to an intermediate gapless QSL with an SFS into a PPM phase ( to large , respectively). (D) Average spin-spin correlations between sites at a fixed distance of . The dashed black line represents the power law decay with power −1.5 as a guide to the eye. All results were obtained using DMRG at zero temperature.

Model and Method

We consider the Kitaev model on a honeycomb lattice in the presence of an external magnetic field along the [111] direction. The model Hamiltonian is defined as

| [1] |

where is the nearest neighbor bond index of each site and is the projection of spin- degrees of freedom on each site. The first term is the Kitaev model where eV, and the second term represents Zeeman field with a uniform magnetic field (in units of ) applied in the direction, i.e., perpendicular to the two-dimensional honeycomb lattice. This model is solved using density matrix renormalization group (DMRG) and Lanczos on a lattice with number of unit cells and with two sites per unit cell labeled as or (the total number of sites equals ) (see Fig. 3A). All DMRG simulations are performed with fixed and cylindrical boundary conditions using up to 1,200 DMRG states per block, ensuring the truncation error for ( sites in direction) within the two-site grand canonical DMRG (36–43). Additionally, we also use finite-temperature Lanczos method (FTLM) for calculations of specific heat and thermodynamic entropy at finite temperatures (in units of ) on small clusters (39, 44). SI Appendix presents definitions of all observables and convergence analysis of DMRG and FTLM calculations.

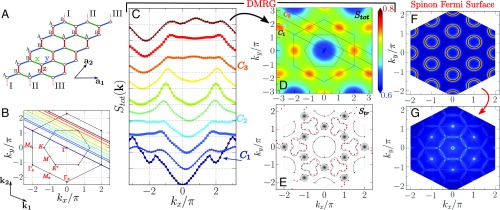

Fig. 3.

The spin structure factor and deduced SFS in the intermediate phase. A shows the honeycomb lattice with cylindrical boundary conditions with L2 = 3, 4, 5 (6, 8, 10 sites in the direction), shown here for . The unit vectors are and . The spin structure factor in C shown along the crystal momentum cuts in B within the extended BZ at fixed in the intermediate phase. These cuts are defined using the reciprocal lattice vectors and , where circles, squares, and triangles represent cuts obtained using L2 = 3, 4, 5, respectively. The high-symmetry points of the BZ and extended BZ are also labeled in B. D shows a contour plot of , with blue representing low intensity and red representing high intensity. The diagonal lines are special cuts , and defined in C. (E) The peak locations (red points) of the intrasublattice structure factor , where gray circles at points represent large peaks. (F) Proposed SFS with pockets around and points, assuming that sublattices and are equivalent as in the Kitaev model. (G) Scattering spectrum of the proposed SFS calculated using . The proposed SFS reproduces robust peaks at points of the BZ and circular patterns around the points, similar to the DMRG results in E.

Results

We begin with the magnetic and thermodynamic properties of the model. Fig. 1 shows the spin susceptibility () and various measures of magnetization as a function of field strength . The clear two-peak structure of demonstrates the presence of two-phase transitions at finite field strengths. The corresponding magnetization also shows kinks at the critical fields and 0.35 (dashed lines in Fig. 1 A and B). The zero field limit is known to be a QSL with a gapless energy spectrum and fourfold topological ground-state degeneracy that is associated with a symmetry-protected topological phase (1). At finite fields , the ground state is twofold degenerate on a cylinder, and the energy spectrum becomes gapped (1, 32). The gapped phase is also understood to be a state of the emergent fermions. For high fields , we find a partially polarized magnetic (PPM) phase, where the magnetization monotonically increases toward its saturation value () in the trivially field-polarized product state. Remarkably, the two-peak structure of indicates that an intermediate phase is sandwiched between the gapped Kitaev QSL and polarized phases (Fig. 1C).

What are the properties of the intermediate phase? We study the decay of spin-spin correlations shown as a function of the distance between the two spins in Fig. 1D. As expected, in the gapped nonabelian QSL phase (), the decays exponentially, consistent with a finite gap to flux excitations (4, 30, 33, 45). In the PPM phase, the behavior of is consistent with an exponential decay due to short-ranged spin-spin correlations arising from the energy cost for a spin flip that is proportional to . However, in the intermediate regime, the behavior of is approximately fit as a power law with shown by the dashed black line in Fig. 1D. SI Appendix shows more detained fitting analysis of , where is weakly dependent on the field in the intermediate phase.

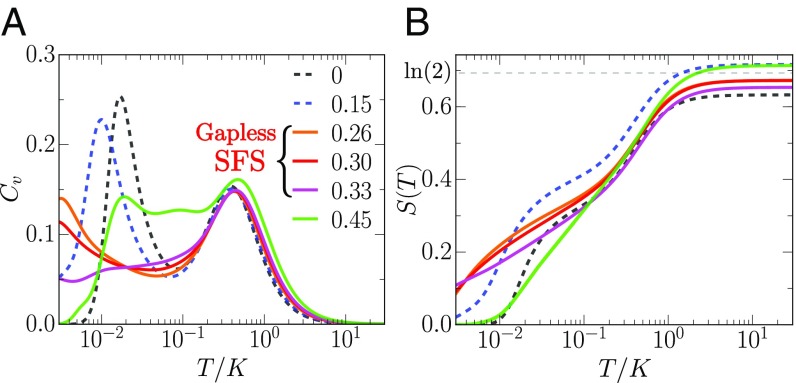

We provide further evidence of the gapless nature of excitations in Fig. 2 through the temperature-dependent specific heat and the thermodynamic entropy . We capture the characteristic two-peak structure of and two hump structures in the entropy at zero field. As expected, saturates to at large temperatures for all field values. The two-peak/hump feature is also found in the gapped QSL phase (), where low-temperature peak/hump shifts to even lower temperatures compared with . The behavior of the low-temperature and is consistent with a gapped spectrum both at low and high fields. However in the intermediate phase, the peak at low is suppressed, leading to an algebraic behavior that is distinct compared with both gapped phases. In fact, the low-temperature at shows linear behavior in temperature (shown in SI Appendix with a linear temperature scale) that is consistent with a gapless phase. As the FTLM is limited to small system sizes, severe size effects prevent us from obtaining an exact dependence of on temperature, and therefore, we only discuss the qualitative trends. The analysis of the statistical error in calculations of and is also shown in SI Appendix along with at low temperatures. Finally, with increasing across into the PPM phase (), the two peaks in merge, and similarly, only one hump feature is visible in the entropy.

Fig. 2.

Specific heat and thermodynamic entropy as a function of temperature . Shown results are using a unit cell (18 sites) cluster solved using FTLM averaged over 50 different random runs (39, 44) for each fixed magnetic field strength (key label).

We also analyze the low-temperature missing part of the entropy () resulting from finite size effects (shown in SI Appendix). The and gapped phases have a quadratic increase in with temperature. On the contrary, the intermediate phase shows almost a linear behavior of at low temperatures. This is consistent with our earlier arguments of gapless nature of the intermediate phase. To summarize, we observe the following features in the intermediate phase: (i) a slow power law decay of the (Fig. 1D) that is indicative of a gapless phase and (ii) a consistent with linear behavior at low indicating a presence of itinerant emergent fermions. All of this evidence taken together provides strong evidence for an intermediate phase that is indeed gapless. Additionally, recently calculated spin dynamics on small systems also show a continuum in energy, suggesting that the intermediate phase is indeed a gapless QSL (30). In fact, such gapless spin liquid phase on a triangular lattice was recently shown to have stable SFS (46, 47). Therefore, it is likely that even in our case, on a honeycomb lattice, we may have an SFS as discussed before.

To explore this possibility, we calculate the spin structure factor along various cuts of the Brillouin zone (BZ) in Fig. 3. For two sites per unit cell ( and ), we define structure factor using Fourier transform of inter- and intrasublattice spin-spin correlations. The calculation of (trace) is performed using only intrasublattice correlations, while (total) sums over both inter- and intrasublattice correlations (SI Appendix). Note that the sublattices and are located on different positions within a unit cell (unlike orbitals), and therefore, must be considered in the extended BZ scheme (Fig. 3 B–D), while the may be considered only using the first BZ (Fig. 3E). In short, , but , where and refer to high-symmetry points in the first and extended BZs, respectively, labeled in Fig. 3B. We shall use subscript e to distinguish between high-symmetry points of the extended BZ vs. the first BZ.

In Fig. 3 C and D, we show cuts and contour of the at fixed in the intermediate phase [SI Appendix has cuts of the ]. There is suppression of intensity around the point and peaks around the points. The cuts between and pass through two points, showing robust peaks visible in Fig. 3C, green curve. at all of the points is distinctly visible as high-intensity red circles in Fig. 3D. Apart from the total spin structure factor , we also analyze the peak locations of the trace spin structure factor that respects symmetries within the first BZ. Fig. 3E shows large peaks at the points of the first BZ, with soft peaks around the and points forming three petal-shaped patterns and peaks around forming a circle. In fact, comparing Fig. 3 D and E, it can be observed that the dominant peaks at the points in simply shift to the points when considering the that also retains the intersublattice correlations.

Given the information provided by and , we propose the corresponding SFS with pockets around and points of the BZ (Fig. 3F). Using the spinon spectral function, defined by , we construct the scattering function in Fig. 3G, , that picks up the momentum transfer from to scattering across the Fermi surface with energy transfer . The interpocket scattering and across the SFS (Fig. 3F) leads to a large joint density of states with momentum transfer that results in peaks at the points (Fig. 3G), consistent with our DMRG calculations of in the intermediate phase (Fig. 3E). Other large circular features in arise from similar scattering processes: for example, a spinon with momentum around the pocket can scatter to all points within the pockets at the points. The combination of these large circular features leads to the three-petal patterns also found in at the points (Fig. 3E). In summary, our proposed SFS is able to qualitatively capture even subtle features of the in the intermediate phase, providing strong evidence for a QSL with an SFS shown in Fig. 3F.

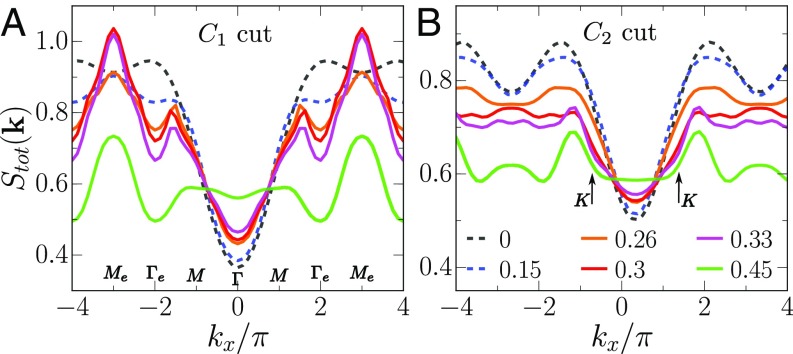

We next turn to the effect of a magnetic field on the spin structure factor. Fig. 4 shows for cut and cut at various field strengths . Note that, for zero fields gapless and gapped QSL phases, there is a broad feature that is consistent with short-ranged correlations established by an exponential decay of spin-spin correlations in real space (Fig. 1C). Our result is also consistent with previous calculations of peaks in the dynamical structure factor arising from plaquette flux and Majorana excitations (33) that, on integrating , give the broad feature in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

for various field strengths along (A) cut and (B) cut (defined in Fig. 3D). The peaks at points are most robust for the intermediate phases , and 0.33. The peak/hump-like feature close to points monotonically decreases with increasing .

The intermediate phase with long-range correlations shows robust peaks at (Fig. 4A). Additionally, Fig. 4B demonstrates that the plateau at momentum point monotonically decreases with an increasing magnetic field. On the other hand, increases with the field, reaching its maximum value in the intermediate phase and decreasing again on transitioning into PPM phase. All peaks get suppressed in the PPM phase, as expected, because of shorter-ranged spin-spin correlations (Fig. 1D). Overall, the combined results of Figs. 3 and 4 show that the dominant peaks of the spin structure factor at the points exist only in the intermediate gapless phase.

Discussion

Several conflicting values of the central charge have been reported for the intermediate phase, where arguments based on the central charge were used to deduce the SFS (33–35). However, it seems to be very difficult to obtain a reliable value for unambiguously in a gapless phase using DMRG. Ref. 34 proposes c = 1, 0 using L2 = 3, 4, respectively; ref. 33 finds a using ; and ref. 35 calculates c = 1, 2 using L2 = 2, 3, respectively, using DMRG. Based on the central charge arguments, the SFS was argued to have pockets around the and points of the first BZ (34, 35). This clearly differs from our proposal of the SFS with pockets around and points; our results are also consistent with the exact diagonalization results of the dynamical structure factor on small clusters (30). We further emphasize that the total must respect the symmetries within the extended BZ because of two atoms in the unit cell at different locations for a honeycomb lattice (Fig. 3A), a point that seems to have been ignored in the literature.

We note that the surfaces shown in Fig. 3 D and E cannot result from the tight-binding model with uniform hopping on a honeycomb lattice (the graphene problem). This is because any scattering will only lead to with peaks at the and points, which are not present in our DMRG calculations of in the intermediate phase. To have peaks at the point in , as we have found in our calculations, there must be pockets around the points of the SFS. Note that all of the points in the BZ are related by rotation and momentum translation symmetries and therefore, must be identical. Such a SFS with scattering will produce a peak with momentum transfer around the point in . Moreover, the size of pockets on the SFS is picked such that more subtle three petal-shaped patterns around the points (Fig. 3E) are also captured in (Fig. 3G). In the graphene problem, the Dirac points at the are protected by inversion and time-reversal symmetry. However, the magnetic field breaks time-reversal symmetry, allowing for the possibility of shifting the pocket positions away from the points. Additionally, we expect the largest scattering contribution to occur between a particle and hole pocket. In summary, we propose an SFS with two bands, creating Fermi pockets at the point and with opposite particle and hole character (Fig. 3F).

The procedure described above for the reconstruction of the SFS relies on the assumption that the integrated is well described by the dynamical correlations at low energies, also used previously to propose an SFS in 1T- (46). In the Kitaev model (at zero field), indeed most of the weight in is concentrated at small (4). We test this assumption in the new QSL phase by calculating the numerically challenging dynamical spin structure factor (48, 49) at low energies on unit cell (48 sites) clusters. We find that the dynamical spin structure factor also shows peaks at the points for (SI Appendix), justifying our method to reconstruct the SFS.

We expect the emergent neutral fermions that form a Fermi surface in the gapless QSL phase to show quantum oscillations in a magnetic field, similar to observations of quantum oscillations in , a topological Kondo insulator (50–52). Going forward, it would also be useful to dope the different classes of Mott insulators that could harbor QSL ground states to explore the emergent superconducting phases (53).

Conclusion

Our most significant finding is that of an intermediate gapless QSL with an SFS sandwiched between the well-known gapped nonabelian Kitaev spin liquid at low magnetic fields and a partially polarized phase at high magnetic fields, studied here for a field along the [111] direction. The two quantum-phase transitions are revealed by kinks in the magnetization and peaks in the susceptibility. The gapless nature of the intermediate phase is indicated by the slow power law decay of spin-spin correlations as opposed to an exponential decay in the other two phases. The temperature dependence of the thermodynamic quantities, specific heat and entropy, also corroborates the gapless nature of this intermediate phase.

Finally, using large-scale DMRG and detailed analysis along many cuts of the spin structure factor in momentum space, we propose an SFS in the intermediate phase with pockets at the and points with opposite particle hole character. We expect our findings to encourage the search for QSLs in materials with Kitaev interactions via spectroscopy and thermodynamic measurements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kyungmin Lee and David C. Ronquillo for their helpful comments and discussions. We also thank Gonzalo Alvarez for help with DMRG++ open source code developed at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. N.D.P. and N.T. acknowledge support from Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02-07ER46423. Computations were performed using Unity cluster at The Ohio State University and the Ohio supercomputer.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1821406116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kitaev A., Anyons in an exactly solved model and beyond. Ann. Phys. 321, 2–111 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savary L., Balents L., Quantum spin liquids: A review. Rep. Prog. Phys., 80, 016502 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou Y., Kanoda K., Ng T. K., Quantum spin liquid states. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 025003 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knolle J., Dynamics of a Quantum Spin Liquid (Springer International Publishing, ed.1, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knolle J., Moessner R., A field guide to spin liquids. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 10, 451–472 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackeli G., Khaliullin G., Mott insulators in the strong spin-orbit coupling limit: From Heisenberg to a quantum compass and Kitaev models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 017205 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun S. H., et al. , Direct evidence for dominant bond-directional interactions in a honeycomb lattice iridate . Nat. Phys. 11, 462–466 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye F., et al. , Direct evidence of a zigzag spin-chain structure in the honeycomb lattice: A neutron and x-ray diffraction investigation of single-crystal Na2IrO3. Phys. Rev. B 85, 180403 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi S. K., et al. , Spin waves and revised crystal structure of honeycomb iridate Na2IrO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 127204 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee A., et al. , Neutron scattering in the proximate quantum spin liquid -RuCl3. Science 356, 1055–1059 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winter S. M., et al. , Models and materials for generalized Kitaev magnetism. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 493002 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trebst S., Kitaev materials. arXiv:1701.07056 (24 January 2017).

- 13.Misguich G., Lhuillier C., Bernu B., Waldtmann C., Spin-liquid phase of the multiple-spin exchange Hamiltonian on the triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. B 60, 1064–1074 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morita H., Watanabe S., Imada M., Nonmagnetic insulating states near the Mott transitions on lattices with geometrical frustration and implications for -(ET)2Cu2 (CN)3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 71, 2109–2112 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motrunich O. I., Variational study of triangular lattice spin model with ring exchanges and spin liquid state in -(ET)2Cu2 (CN)3. Phys. Rev. B 72, 045105 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimizu Y., Miyagawa K., Kanoda K., Maesato M., Saito G., Spin liquid state in an organic Mott insulator with a triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett., 91, 107001 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helton J. S., et al. , Spin dynamics of the spin- kagome lattice antiferromagnet . Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 107204 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi Y., Xu C., Sachdev S., Dynamics and transport of the spin liquid: Application to . Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 176401 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Law K. T., Lee P. A., 1T- as a quantum spin liquid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 6996–7000 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimizu Y., Miyagawa K., Kanoda K., Maesato M., Saito G., Spin liquid state in an organic Mott insulator with a triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 107001 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itou T., Oyamada A., Maegawa S., Tamura M., Kato R., Quantum spin liquid in the spin- triangular antiferromagnet . Phys. Rev. B 77, 104413 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W., et al. , Rare-earth chalcogenides: A large family of triangular lattice spin liquid candidates. Chin. Phys. Lett. 35, 117501 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasahara Y., et al. , Majorana quantization and half-integer thermal quantum hall effect in a Kitaev spin liquid. Nature 559, 227–231 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janša N., et al. , Observation of two types of fractional excitation in the Kitaev honeycomb magnet. Nat. Phys. 14, 786–790 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolter A. U. B., et al. , Field-induced quantum criticality in the Kitaev system . Phys. Rev. B 96, 041405 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Z. X., Normand B., Dirac and chiral quantum spin liquids on the honeycomb lattice in a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 187201 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon J. S., Catuneanu A., Sørensen E. S., Kee H. Y., Theory of the field-revealed Kitaev spin liquid. arXiv:1901.09943v1 (28 January 2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Jiang Y. F., Devereaux T. P., Jiang H. C., Field-induced quantum spin liquid in the Kitaev-Heisenberg model and its relation to . arXiv:1901.09131v1 (26 January 2019).

- 29.Takikawa D., Fujimoto S., Impact of off-diagonal exchange interactions on the Kitaev spin liquid state of . arXiv:1902.06433v2 (18 February 2019).

- 30.Hickey C., Trebst S., Emergence of a field-driven U(1) spin liquid in the Kitaev honeycomb model. Nat. Commun. 10, 530 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ronquillo D. C., Vengal A., Trivedi N., Signatures of magnetic-field-driven quantum phase transitions in the entanglement entropy and spin dynamics of the Kitaev honeycomb model. Phys. Rev. B 99, 140413(R) (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu Z., Kimchi I., Sheng D. N., Fu L., Robust non-abelian spin liquid and a possible intermediate phase in the antiferromagnetic Kitaev model with magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 97, 241110 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gohlke M., Moessner R., Pollmann F., Dynamical and topological properties of the Kitaev model in a [111] magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 98, 014418 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang H. C., Wang C. Y., Huang B., Lu Y. M., Field induced quantum spin liquid with spinon Fermi surfaces in the Kitaev model. arXiv:1809.08247 (2 October 2018).

- 35.Zou L., He Y. C., Field-induced neutral Fermi surface and -Chern-Simons quantum criticalities in Kitaev materials. arXiv:1809.09091 (3 October 2018).

- 36.White S. R., Density matrix formulation for quantum renormalization groups. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2863–2866 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White S. R., Density-matrix algorithms for quantum renormalization groups. Phys. Rev. B 48, 10345–10356 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White S. R., Spin gaps in a frustrated Heisenberg model for . Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3633–3636 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avella A., Mancini F., Strongly Correlated Systems: Numerical Methods (Springer Series in Solid-State Sciences, Springer, Berlin, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alvarez G., The density matrix renormalization group for strongly correlated electron systems: A generic implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 1572–1578 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 41.D’Azevedo E. F., Elwasif W. R., Patel N. D., Alvarez G., Targeting multiple states in the density matrix renormalization group with the singular value decomposition. arXiv:1902.09621v1 (25 February 2019).

- 42.Schollwöck U., The density-matrix renormalization group. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 259–315 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schollwöck U., The density-matrix renormalization group in the age of matrix product states. Ann. Phys. 326, 96–192 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jaklič J., Prelovšek P., Lanczos method for the calculation of finite-temperature quantities in correlated systems. Phys. Rev. B 49, 5065–5068 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hermanns M., Kimchi I., Knolle J., Physics of the Kitaev model: Fractionalization, dynamic correlations, and material connections. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 9, 17–33 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 46.He W. Y., Xu X. Y., Chen G., Law K. T., Lee P. A., Spinon Fermi surface in a cluster Mott insulator model on a triangular lattice and possible application to . Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 046401 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Block M. S., Sheng D. N., Motrunich O. I., Fisher M. P. A., Spin Bose-metal and valence bond solid phases in a spin model with ring exchanges on a four-leg triangular ladder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 157202 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nocera A., Alvarez G., Spectral functions with the density matrix renormalization group: Krylov-space approach for correction vectors. Phys. Rev. E 94, 053308 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kühner T. D., White S. R., Dynamical correlation functions using the density matrix renormalization group. Phys. Rev. B 60, 335–343 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knolle J., Cooper N. R., Excitons in topological Kondo insulators: Theory of thermodynamic and transport anomalies in . Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 096604 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li G., et al. , Two-dimensional fermi surfaces in Kondo insulator . Science 346, 1208–1212 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Erten O., Ghaemi P., Coleman P., Kondo breakdown and quantum oscillations in . Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 046403 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Metlitski M. A., Mross D. F., Sachdev S., Senthil T., Cooper pairing in non-Fermi liquids. Phys. Rev. B 91, 115111 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.