Abstract

Pancreatic cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer death worldwide. Adjuvant chemotherapy has been developed based on the experiences made with palliative chemotherapy, and advocated to improve long-term survival of patients with this disease. However, the optimal chemotherapeutic regimen remains controversial. Recently, Conroy et al demonstrated the impressive benefits of modified FOLFIRINOX over gemcitabine alone in the multicenter Partenariat de Recherche en Oncologie Digestive 24 (PRODIGE-24) trial. The remarkable results mark a new milestone in treating resectable pancreatic cancer and have now changed the standard of care for this patient population. In this commentary, we discuss an issue of difference of tumor grade between the PRODIGE-24 trial and previous phase III trials. We also discuss potential biomarkers predicting therapeutic response to modified FOLFIRINOX. Finally, we summarize several ongoing clinical trials of replacing part of the FOLFIRINOX regimen with Xeloda/S-1/nanoliposomal irinotecan for pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Adjuvant therapy, FOLFIRINOX, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte, Nanoliposomal irinotecan

Core tip: Adjuvant chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer has been developed based on the experiences made with palliative chemotherapy. Nevertheless, the optimal regimen remains controversial. The Partenariat de Recherche en Oncologie Digestive 24 trial showed an impressive benefit of modified FOLFIRINOX over gemcitabine alone. The remarkable results mark a new milestone in treating resectable pancreatic cancer and have now changed the standard of care. Here, we discuss an issue of difference between this trial and previous phase III trials, as well as potential biomarkers predicting therapeutic response. Several ongoing trials of replacing part of the FOLFIRINOX regimen with other drugs for pancreatic cancer are also summarized.

COMMENTARY ON HOT TOPICS

We have read with great interest the recent article by Conroy et al[1] comparing the efficacy and safety of a modified FOLFIRINOX (oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, leucovorin 400 mg/m2, irinotecan 150 mg/m2, and continuous fluorouracil 2400 mg/m2; without bolus fluorouracil; every 2 wk for 12 cycles) regimen with gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for resected pancreatic cancer, and would strongly recommend it to the readers.

Pancreatic cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer death in both the United States and China[2,3]. The improvement of long-term prognosis of this disease is attributed to the decrease of perioperative mortality[4,5] and the increase of adjuvant treatment rate[6]. Adjuvant chemotherapy has been developed based on the experiences made with palliative chemotherapy, and advocated to reduce recurrence and improve survival after surgery[7]. The European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer 1 (ESPAC-1) trial revealed a superior median survival with chemotherapy (bolus fluorouracil 425 mg/m2 plus leucovorin 20 mg/m2 days 1-5, every 4 wk for six cycles) as compared with no chemotherapy [20.1 mo vs 15.5 mo; hazard ratio (HR) for death = 0.71; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.55-0.92; P = 0.009][8]. The Charité Onkologi 001 (CONKO-001) trial showed a significantly prolonged disease-free survival in the gemcitabine group (1000 mg/m2 days 1, 8, and 15, every 4 wk for six cycles) compared to the observation group (13.4 mo vs 6.9 mo, P < 0.001), but a modest overall survival benefit (22.1 mo vs 20.2 mo, P = 0.06)[9]. The ESPAC-3 trial subsequently showed an absence of overall survival difference between adjuvant gemcitabine and fluorouracil plus folinic acid (23.6 mo vs 23 mo, P = 0.39) in patients with resected pancreatic cancer[10]. With the goal to further prolong postoperative survival, gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapies were evaluated in subsequent trials, such as the ESPAC-4[11] and CONKO-005 trials[12]. However, the optimal chemotherapeutic regimen remains controversial.

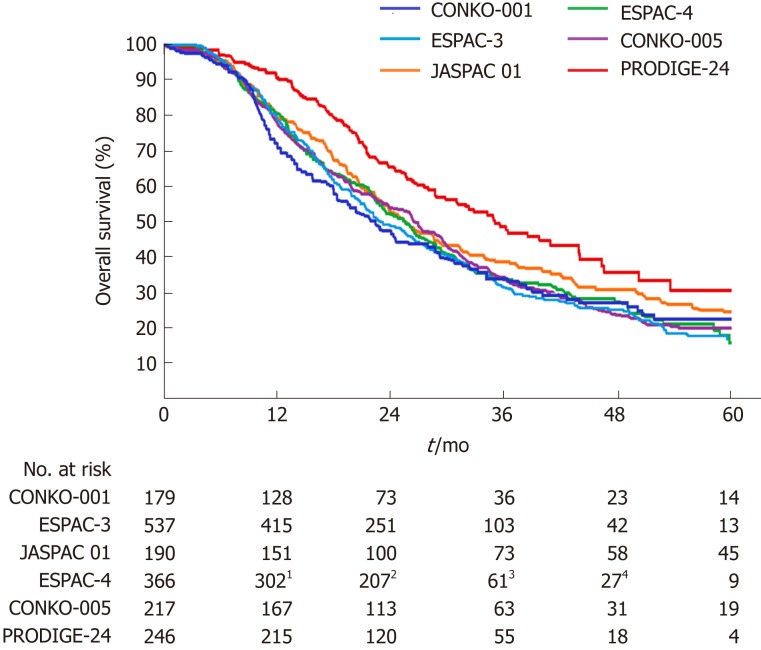

In the Partenariat de Recherche en Oncologie Digestive 24 (PRODIGE-24) trial[1], 493 patients from 77 centers in France and Canada were randomly assigned to receive a modified FOLFIRINOX regimen or gemcitabine for 24 wk. Patients 18 to 79 years of age who had undergone R0 (absence of tumor cells within 1 mm of all resection margins) or R1 (presence of tumor cells within 1 mm of one or more resection margins) resection within 3 to 12 wk before randomization, and who had a serum CA 19-9 level ≤ 180 U/mL were eligible for inclusion. At a median follow-up of 33.6 mo, there was an impressive difference of 18.3% in the disease-free 3-year survival rate (39.7% in the modified FOLFIRINOX group vs 21.4% in the gemcitabine group). The median disease-free survival with the modified FOLFIRINOX regimen was 21.6 mo and with gemcitabine 12.8 mo (stratified HR for cancer-related event, second cancer, or death = 0.58; 95%CI: 0.46-0.73; P < 0.001). The median overall survival was 54.4 mo in the modified FOLFIRINOX group vs 35.0 mo in the gemcitabine group (stratified HR for death = 0.64; 95%CI: 0.48-0.86; P = 0.003). Compared with previous phase III trials[9-13], the PRODIGE-24 trial showed a much longer median overall survival in the gemcitabine group (Figure 1), which the authors attributed to the high use of FOLFIRINOX and other active regimens after tumor relapse. Kindler[14] considered that the similarity of the disease-free survival in the gemcitabine group throughout these trials argued against selection bias. However, we propose that the difference of tumor grade among these trials should not be neglected (Table 1). Tumor grade has been revealed as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival[10,15]. The higher proportion of well-differentiated tumors might account for the improved survival of the gemcitabine group in the PRODIGE-24 trial.

Figure 1.

Overall survival curves for patients receiving gemcitabine alone following pancreatic cancer resection in six phase III randomized clinical trials. 1Data for the 10th month; 2Data for the 20th month; 3Data for the 40th month; 4Data for the 50th month.

Table 1.

Comparison of six phase III clinical trials of gemcitabine alone in patients with resected pancreatic cancer

| Trial | PRODIGE-24[1] | CONKO-001[9] | ESPAC-3[10] | JASPAC 01[13] | ESPAC-4[11] | CONKO-005[12] |

| Variable | ||||||

| No. of patients | 246 | 179 | 537 | 190 | 366 | 217 |

| Tumor grade, n (%) | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 79 (32.1) | 10 (5.6) | 66 (12.3) | NA | 30 (8.2) | 9 (4.1) |

| Moderately differentiated | 125 (50.8) | 103 (57.5) | 336 (62.6) | NA | 192 (52.5) | 128 (59) |

| Poorly differentiated/undifferentiated | 29 (11.8) | 63 (35.2) | 127 (23.6) | NA | 142 (38.8) | 74 (34.1) |

| Disease free survival - mo | ||||||

| Median | 12.8 | 13.4 | 14.3 | 11.3 | 13.1 | 11.4 |

| 95%CI | 11.7-15.2 | 11.4-15.3 | 13.5-15.6 | 9.7-13.6 | 11.6-15.3 | 9.2-13.6 |

| Overall survival - mo | ||||||

| Median | 35.0 | 22.1 | 23.6 | 25.5 | 25.5 | 26.5 |

| 95%CI | 28.7-43.9 | 18.4-25.8 | 21.4-26.4 | 22.5-29.6 | 22.7-27.9 | 22.4-30.6 |

NA: Not available; CI: Confidence interval.

A multicenter study from Europe revealed that the overall survival rates of different chemotherapeutic regimens in real-life settings were lower than those shown in randomized phase III trials[16]. This can be explained by the fact that randomized clinical trials usually have stringent inclusion criteria. Predictive markers in-vestigating therapeutic response to modified FOLFIRINOX would help us guide treatment strategies and improve prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Meanwhile, given the more reported incidences of adverse events in the modified FOLFIRINOX group, it is urgently needed to identify patients who will most likely benefit from this re-gimen. Most recent studies failed to establish tolerability of UGT1A1 genotype-guided modified FOLFIRINOX in pancreatic cancer[17,18]. Interestingly, although the rates of neutropenia and severe lymphopenia were similar between the two groups in the PRODIGE-24 trial[1], the significantly lower occurrence of lymphopenia (any grade) in the modified FOLFIRINOX group indicates a difference of post-treatment change in neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). NLR, a marker of systemic in-flammatory response, has been shown to be a valuable prognostic marker in many malignancies, including pancreatic cancer[19,20]. Baseline and post-treatment NLR may predict therapeutic response to chemotherapy[21-24], including the modified FOLFIRINOX regimen[25], for pancreatic cancer. In their study, Conroy et al[1] showed the treatment benefit favoring modified FOLFIRINOX over gemcitabine in all predefined subgroup analyses. Nevertheless, whether the superiority of the modified FOLFIRINOX regimen is based on difference in the baseline and post-chemotherapy NLR remains unclear, which encourages us to investigate how NLR correlates with response to modified FOLFIRINOX.

The remarkable results of the PRODIGE-24 trial mark a new milestone in treating resectable pancreatic cancer and open a world of possible investigations. Can we further improve survivals by using modified FOLFIRINOX as neoadjuvant chemotherapy? What is the effect of this regimen combined with radiotherapy? Additionally, can we improve the safety and/or efficacy by replacing 5-FU and leucovorin in the FOLFIRINOX regimen with capecitabine (Xeloda) or oral S-1? The triple combination chemotherapy of S-1, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan (SOXIRI) appeared to be a promising and well-tolerated regimen in patients with unresectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma[26,27]. Several phase I and II trials of these particular combinations have been conducted across various stages of pancreatic cancer (Table 2). Lastly, given the theoretical benefits of developing nano-formulations of anti-cancer drugs for cancers[28,29], the applicability of novel agents needs to be evaluated in pancreatic cancer. For example, the proven efficacy of nanoliposomal irinotecan (nal-IRI) in metastatic pancreatic cancer[30,31] has triggered enthusiasm in substituting nal-IRI for standard irinotecan as part of the FOLFIRINOX regimen (Table 2). We look forward to the results of this triple-drug combination regimen in patients with pancreatic cancer.

Table 2.

Ongoing clinical trials of replacing part of the FOLFIRINOX regimen with Xeloda/S-1/Nanoliposomal Irinotecan for pancreatic cancer registered in ClinicalTrials.gov

| Country | Title | Regimen | Phase | Cancer stage | Estimated enrollment | Study completion date | Source |

| China | The combination chemotherapy of S-1, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin as first line chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer | S-1, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin | II | Unresectable or metastatic | 65 | December 2019 | NCT03403101 |

| United States | Neoadjuvant capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan chemotherapy in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma | Capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan | II | Resectable, borderline and locally advanced | 17 | December 2022 | NCT01760252 |

| Singapore | Oxaliplatin, Xeloda, and irinotecan in pancreatic adenocarcinoma | Oxaliplatin, Xeloda, and irinotecan | I | Advanced and/or metastatic | 90 | June 2019 | NCT02368860 |

| Italy | A study of nanoliposomal irinotecan with 5-fluorouracil, levofolinic acid, and oxaliplatin in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer | Nanoliposomal irinotecan, oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil | II | Resectable | 67 | January 2020 | NCT03528785 |

| United States | Study of nanoliposomal irinotecan-containing regimens in patients with previously untreated, metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma | Nanoliposomal irinotecan, oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil | II | Metastatic | 56 | February 2020 | NCT02551991 |

The modified FOLFIRINOX regimen is superior to gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for resected pancreatic cancer, and should be a new standard of care for this patient population. It is worth noting that both modified FOLFIRINOX and nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine have been established as standard first-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer, showing comparable efficacy outcomes[32]. The APACT trial is a phase III, international, multicenter, randomized, open-label, controlled study to compare adjuvant nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs gemcitabine alone in patients with surgically resected pancreatic cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01964430). Eight hundred and sixty-six patients have been randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive six cycles of either nab-paclitaxel 125 mg/m2 plus gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 or gem-citabine alone 1000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 4-wk cycle. The preliminary results will be announced in the near future, and provide us further evidence for adjuvant treatment for resected pancreatic cancer.

Neoadjuvant treatment with FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel has become a standard of care for borderline or locally advanced pancreatic cancer[33,34], and is now increasingly considered even for up-front resectable disease[35-38]. Due to its growing preference over either postoperative chemotherapy regimen, a neoadjuvant approach is advocated when there is the option in order to improve the success of complete tumor resection and for potential control of micrometastases. Studies now in progress will be critical not only to assess the long-term outcomes of current neoadjuvant regimens but also to investigate the added efficacy of anti-stromal agents such as losartan, immunotherapy, radiation therapy, and biomarkers reflecting the response to treatment.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: We declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer-review started: March 7, 2019

First decision: April 5, 2019

Article in press: April 29, 2019

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kleeff J, Kopljar M, Neri V S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Feng Yang, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200040, China. yffudan98@126.com.

Chen Jin, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200040, China.

De-Liang Fu, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200040, China.

Andrew L Warshaw, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, United States.

References

- 1.Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, Ben Abdelghani M, Wei AC, Raoul JL, Choné L, Francois E, Artru P, Biagi JJ, Lecomte T, Assenat E, Faroux R, Ychou M, Volet J, Sauvanet A, Breysacher G, Di Fiore F, Cripps C, Kavan P, Texereau P, Bouhier-Leporrier K, Khemissa-Akouz F, Legoux JL, Juzyna B, Gourgou S, O'Callaghan CJ, Jouffroy-Zeller C, Rat P, Malka D, Castan F, Bachet JB Canadian Cancer Trials Group and the Unicancer-GI–PRODIGE Group. FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2395–2406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin QJ, Yang F, Jin C, Fu DL. Current status and progress of pancreatic cancer in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7988–8003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.7988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang F, Jin C, Li J, Di Y, Zhang J, Fu D. Clinical significance of drain fluid culture after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:508–517. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang F, Jin C, Hao S, Fu D. Drain Contamination after Distal Pancreatectomy: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Association with Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klaiber U, Leonhardt CS, Strobel O, Tjaden C, Hackert T, Neoptolemos JP. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2018;403:917–932. doi: 10.1007/s00423-018-1724-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao WC, Chien KL, Lin YL, Wu MS, Lin JT, Wang HP, Tu YK. Adjuvant treatments for resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1095–1103. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, Bassi C, Dunn JA, Hickey H, Beger H, Fernandez-Cruz L, Dervenis C, Lacaine F, Falconi M, Pederzoli P, Pap A, Spooner D, Kerr DJ, Büchler MW European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1200–1210. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, Gellert K, Langrehr J, Ridwelski K, Schramm H, Fahlke J, Zuelke C, Burkart C, Gutberlet K, Kettner E, Schmalenberg H, Weigang-Koehler K, Bechstein WO, Niedergethmann M, Schmidt-Wolf I, Roll L, Doerken B, Riess H. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, Ghaneh P, Cunningham D, Goldstein D, Padbury R, Moore MJ, Gallinger S, Mariette C, Wente MN, Izbicki JR, Friess H, Lerch MM, Dervenis C, Oláh A, Butturini G, Doi R, Lind PA, Smith D, Valle JW, Palmer DH, Buckels JA, Thompson J, McKay CJ, Rawcliffe CL, Büchler MW European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1073–1081. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, Psarelli EE, Valle JW, Halloran CM, Faluyi O, O'Reilly DA, Cunningham D, Wadsley J, Darby S, Meyer T, Gillmore R, Anthoney A, Lind P, Glimelius B, Falk S, Izbicki JR, Middleton GW, Cummins S, Ross PJ, Wasan H, McDonald A, Crosby T, Ma YT, Patel K, Sherriff D, Soomal R, Borg D, Sothi S, Hammel P, Hackert T, Jackson R, Büchler MW European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinn M, Bahra M, Liersch T, Gellert K, Messmann H, Bechstein W, Waldschmidt D, Jacobasch L, Wilhelm M, Rau BM, Grützmann R, Weinmann A, Maschmeyer G, Pelzer U, Stieler JM, Striefler JK, Ghadimi M, Bischoff S, Dörken B, Oettle H, Riess H. CONKO-005: Adjuvant Chemotherapy With Gemcitabine Plus Erlotinib Versus Gemcitabine Alone in Patients After R0 Resection of Pancreatic Cancer: A Multicenter Randomized Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3330–3337. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.6463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uesaka K, Boku N, Fukutomi A, Okamura Y, Konishi M, Matsumoto I, Kaneoka Y, Shimizu Y, Nakamori S, Sakamoto H, Morinaga S, Kainuma O, Imai K, Sata N, Hishinuma S, Ojima H, Yamaguchi R, Hirano S, Sudo T, Ohashi Y JASPAC 01 Study Group. Adjuvant chemotherapy of S-1 versus gemcitabine for resected pancreatic cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial (JASPAC 01) Lancet. 2016;388:248–257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kindler HL. A Glimmer of Hope for Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2463–2464. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1813684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rochefort MM, Ankeny JS, Kadera BE, Donald GW, Isacoff W, Wainberg ZA, Hines OJ, Donahue TR, Reber HA, Tomlinson JS. Impact of tumor grade on pancreatic cancer prognosis: validation of a novel TNMG staging system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4322–4329. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Javed MA, Beyer G, Le N, Vinci A, Wong H, Palmer D, Morgan RD, Lamarca A, Hubner RA, Valle JW, Alam S, Chowdhury S, Ma YT, Archibugi L, Capurso G, Maisonneuve P, Neesse A, Sund M, Schober M, Krug S. Impact of intensified chemotherapy in metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) in clinical routine in Europe. Pancreatology. 2019;19:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma MR, Joshi SS, Karrison TG, Allen K, Suh G, Marsh R, Kozloff MF, Polite BN, Catenacci DVT, Kindler HL. A UGT1A1 genotype-guided dosing study of modified FOLFIRINOX in previously untreated patients with advanced gastrointestinal malignancies. Cancer. 2019 doi: 10.1002/cncr.31938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirasu H, Todaka A, Omae K, Fujii H, Mizuno N, Ozaka M, Ueno H, Kobayashi S, Uesugi K, Kobayashi N, Hayashi H, Sudo K, Okano N, Horita Y, Kamei K, Yukisawa S, Kobayashi M, Fukutomi A. Impact of UGT1A1 genetic polymorphism on toxicity in unresectable pancreatic cancer patients undergoing FOLFIRINOX. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:707–716. doi: 10.1111/cas.13883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JM, Lee HS, Hyun JJ, Choi HS, Kim ES, Keum B, Seo YS, Jeen YT, Chun HJ, Um SH, Kim CD. Prognostic value of inflammation-based markers in patients with pancreatic cancer administered gemcitabine and erlotinib. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8:555–562. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i7.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shirai Y, Shiba H, Sakamoto T, Horiuchi T, Haruki K, Fujiwara Y, Futagawa Y, Ohashi T, Yanaga K. Preoperative platelet to lymphocyte ratio predicts outcome of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma after pancreatic resection. Surgery. 2015;158:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein D, El-Maraghi RH, Hammel P, Heinemann V, Kunzmann V, Sastre J, Scheithauer W, Siena S, Tabernero J, Teixeira L, Tortora G, Van Laethem JL, Young R, Penenberg DN, Lu B, Romano A, Von Hoff DD. nab-Paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer: long-term survival from a phase III trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015:107. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo G, Guo M, Liu Z, Xiao Z, Jin K, Long J, Liu L, Liu C, Xu J, Ni Q, Yu X. Blood neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:670–676. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4021-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y, Yan H, Wang Y, Shi Y, Dai G. Significance of baseline and change in neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in predicting prognosis: a retrospective analysis in advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 2017;7:753. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00859-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi Y, Oh DY, Park H, Kim TY, Lee KH, Han SW, Im SA, Kim TY, Bang YJ. More Accurate Prediction of Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Patients' Survival with Prognostic Model Using Both Host Immunity and Tumor Metabolic Activity. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0145692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Jesus VHF, Camandaroba MPG, Donadio MDS, Cabral A, Muniz TP, de Moura Leite L, Sant'Ana LF. Retrospective comparison of the efficacy and the toxicity of standard and modified FOLFIRINOX regimens in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;9:694–707. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2018.04.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yanagimoto H, Satoi S, Sho M, Akahori T, Yamamoto T, Hirooka S, Yamaki S, Kotsuka M, Ryota H, Kinoshita S, Nishiwada S, Nagai M, Ikeda N, Tsuta K, Nakajima Y, Kon M. Phase I study assessing the feasibility of the triple combination chemotherapy of SOXIRI (S-1/oxaliplatin/irinotecan) in patients with unresectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77:35–41. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2928-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akahori T, Sho M, Yanagimoto H, Satoi S, Nagai M, Nishiwada S, Nakagawa K, Nakamura K, Yamamoto T, Hirooka S, Yamaki S, Ikeda N. Phase II Study of the Triple Combination Chemotherapy of SOXIRI (S-1/Oxaliplatin/Irinotecan) in Patients with Unresectable Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2019 doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang F, Jin C, Jiang Y, Li J, Di Y, Ni Q, Fu D. Liposome based delivery systems in pancreatic cancer treatment: from bench to bedside. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37:633–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang F, Jin C, Subedi S, Lee CL, Wang Q, Jiang Y, Li J, Di Y, Fu D. Emerging inorganic nanomaterials for pancreatic cancer diagnosis and treatment. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:566–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang-Gillam A, Li CP, Bodoky G, Dean A, Shan YS, Jameson G, Macarulla T, Lee KH, Cunningham D, Blanc JF, Hubner RA, Chiu CF, Schwartsmann G, Siveke JT, Braiteh F, Moyo V, Belanger B, Dhindsa N, Bayever E, Von Hoff DD, Chen LT NAPOLI-1 Study Group. Nanoliposomal irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer after previous gemcitabine-based therapy (NAPOLI-1): a global, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:545–557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang-Gillam A, Hubner RA, Siveke JT, Von Hoff DD, Belanger B, de Jong FA, Mirakhur B, Chen LT. NAPOLI-1 phase 3 study of liposomal irinotecan in metastatic pancreatic cancer: Final overall survival analysis and characteristics of long-term survivors. Eur J Cancer. 2019;108:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang J, Hwang I, Yoo C, Kim KP, Jeong JH, Chang HM, Lee SS, Park DH, Song TJ, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Hong SM, Shin SH, Hwang DW, Song KB, Lee JH, Kim SC, Ryoo BY. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus FOLFIRINOX as the first-line chemotherapy for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: retrospective analysis. Invest New Drugs. 2018;36:732–741. doi: 10.1007/s10637-018-0598-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michelakos T, Pergolini I, Castillo CF, Honselmann KC, Cai L, Deshpande V, Wo JY, Ryan DP, Allen JN, Blaszkowsky LS, Clark JW, Murphy JE, Nipp RD, Parikh A, Qadan M, Warshaw AL, Hong TS, Lillemoe KD, Ferrone CR. Predictors of Resectability and Survival in Patients With Borderline and Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer who Underwent Neoadjuvant Treatment With FOLFIRINOX. Ann Surg. 2019;269:733–740. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Truty MJ, Kendrick ML, Nagorney DM, Smoot RL, Cleary SP, Graham RP, Goenka AH, Hallemeier CL, Haddock MG, Harmsen WS, Mahipal A, McWilliams RR, Halfdanarson TR, Grothey AF. Factors Predicting Response, Perioperative Outcomes, and Survival Following Total Neoadjuvant Therapy for Borderline/Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Ann Surg. 2019 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casadei R, Di Marco M, Ricci C, Santini D, Serra C, Calculli L, D'Ambra M, Guido A, Morselli-Labate AM, Minni F. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy and Surgery Versus Surgery Alone in Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: A Single-Center Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial Which Failed to Achieve Accrual Targets. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1802–1812. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2890-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papalezova KT, Tyler DS, Blazer DG, 3rd, Clary BM, Czito BG, Hurwitz HI, Uronis HE, Pappas TN, Willett CG, White RR. Does preoperative therapy optimize outcomes in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer? J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:111–118. doi: 10.1002/jso.23044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Motoi F, Unno M, Takahashi H, Okada T, Wada K, Sho M, Nagano H, Matsumoto I, Satoi S, Murakami Y, Kishiwada M, Honda G, Kinoshita H, Baba H, Hishinuma S, Kitago M, Tajima H, Shinchi H, Takamori H, Kosuge T, Yamaue H, Takada T. Influence of preoperative anti-cancer therapy on resectability and perioperative outcomes in patients with pancreatic cancer: project study by the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:148–158. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mokdad AA, Minter RM, Zhu H, Augustine MM, Porembka MR, Wang SC, Yopp AC, Mansour JC, Choti MA, Polanco PM. Neoadjuvant Therapy Followed by Resection Versus Upfront Resection for Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: A Propensity Score Matched Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:515–522. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]