Significance

Do corporate sexual harassment programs reduce harassment? Those that do should boost the share of women in management, because harassment causes women to quit. Sexual harassment grievance procedures incite retaliation, according to surveys, and our analyses show that they are followed by reductions in women managers. Sexual harassment training for managers, which treats managers as victims’ allies and gives them tools to intervene, are followed by increases in women managers. Training for employees, which treats trainees as suspects, can backfire. Programs work better in workplaces with more women managers, who are less likely than men to respond negatively to harassment complaints and training. Employers should select managers—men and women—committed to eradicating harassment.

Keywords: sexual harassment, workforce diversity, grievance procedure, harassment training

Abstract

Two decades ago, the Supreme Court vetted the workplace harassment programs popular at the time: sexual harassment grievance procedures and training. However, harassment at work remains common. Do these programs reduce harassment? Program effects have been difficult to measure, but, because women frequently quit their jobs after being harassed, programs that reduce harassment should help firms retain current and aspiring women managers. Thus, effective programs should be followed by increases in women managers. We analyze data from 805 companies over 32 y to explore how new sexual harassment programs affect the representation of white, black, Hispanic, and Asian-American women in management. We find support for several propositions. First, sexual harassment grievance procedures, shown in surveys to incite retaliation without satisfying complainants, are followed by decreases in women managers. Second, training for managers, which encourages managers to look for signs of trouble and intervene, is followed by increases in women managers. Third, employee training, which proscribes specific behaviors and signals that male trainees are potential perpetrators, is followed by decreases in women managers. Two propositions specify how management composition moderates program effects. One, because women are more likely to believe harassment complaints and less likely to respond negatively to training, in firms with more women managers, programs work better. Two, in firms with more women managers, harassment programs may activate group threat and backlash against some groups of women. Positive and negative program effects are found in different sorts of workplaces.

In 1998, the Supreme Court vetted the two most popular corporate sexual harassment programs, sexual harassment grievance procedures and training. By then, 95% of companies had grievance procedures and 74% had training (1). It is hard to know whether these programs have helped, because harassment program effects, and harassment itself, are notoriously difficult to measure. Training and grievance systems may appear to backfire because, by increasing recognition of harassment, they increase complaints (2, 3). Surveys may not pick up harassment in workplaces where it is common because rampant harassment can foster psychological denial (4). While harassment is hard to measure, and thus program effects are hard to gauge, some studies suggest that grievance procedures and training may not reduce harassment. Early evidence came from surveys of federal workers in 1980, 1987, and 1994. Training and grievance protocols were virtually unknown in 1980, but, by 1987, three-quarters of federal workers had completed training, and, by 1994, four-fifths knew how to file a grievance. Did harassment decline? When asked about six specific forms of harassment, 42% of women reported in both 1980 and 1987 that they had been harassed in the past 2 y. In 1994, 44% reported the same (5–7). Much of the subsequent research also suggests that sexual harassment grievance procedures and training may be managerial snake oil. We review this research to develop predictions.

To assess whether harassment grievance procedures and training for managers and employees have reduced harassment we estimate the effects of these programs on the share of women in management. Because it often causes women to leave their jobs (4, 7, 8), harassment should reduce women in management. Programs that reduce harassment should increase women in management.

We develop five predictions based on laboratory and field studies. The first concerns sexual harassment grievance procedures, which give victims a formal avenue for filing complaints. Survey research points to four problems. First, women distrust grievance procedures and rarely file complaints (9). Second, formal complaints rarely lead to the transfer or removal of the harasser (9, 10). Third, women who do file complaints face retaliation—66% of them, according to one survey of federal workers (11). Finally, the adversarial grievance process itself can harm victims; studies comparing women who file complaints to women who keep quiet show worse career, mental health, and health outcomes for those who file (7, 8). Grievance procedures should make it more likely that women will leave their jobs, reducing women in management.

The second prediction concerns sexual harassment training for managers which, while little studied itself, resembles bystander intervention training in important ways. It treats trainees as victims’ allies, reviewing how to prevent harassment, recognize its signs, intervene to stop it, and use grievance processes (12). “If you see something, say something” curriculum has been studied extensively among college students and military personnel. A metaanalysis of campus field studies finds that it increases reported trainee efficacy, intention to intervene, and helping behavior (13). One study showed increased intention to intervene and confidence about intervening after a year (14). Four months out, Army trainees were more likely to report having intervened to stop sexual assault or stalking (15). We expect manager training to provide managers with tools to address harassment, and thus to be followed by increases in women in management.

The third prediction concerns employee training, which typically reviews harassment law, specifies verboten actions, and outlines complaint processes and punishments (16). The message is that employees are potential perpetrators, not victims’ allies. Most laboratory experiments examine this type of training. It can improve recognition of harassment and knowledge about employer policy and complaint processes (17, 18). However, men who score high on “likely harasser” and “gender role conflict” scales—the men trainers hope to reform—frequently have adverse reactions to this sort of “forbidden behavior” training, scoring higher afterward (19, 20). Thus, any positive training effects may be reversed by backlash. We expect employee training to be more likely than manager training to have adverse effects.

Two final predictions address how the gender composition of management moderates program effects. The fourth concerns how managers respond to harassment grievances and training. Research shows that men often don’t believe women who complain of harassment, thinking they have overreacted or have extortion in mind. Women are less likely to buy into to these “harassment myths” (21–23). Thus, we expect that women managers will handle reports of harassment better than men, which will improve the efficacy of grievance procedures. Men may also respond poorly to sexual harassment training. Training has been shown to make men less likely to see coercion of a subordinate as sexual harassment, less likely to report harassment, and more likely to blame the victim (18). This is not so for women. Training can also incite backlash against women and activate gender stereotypes (24). Training, like grievance procedures, should be more effective in workplaces with more women managers.

The fifth prediction modifies the fourth and concerns group threat. For Blalock, when members of the dominant group feel threatened, they may resist the group perceived as a threat (25). He describes a tipping point beyond which the majority group resists. Where might that tipping point be? Kanter argues that, when women hold 15 to 35% of jobs, they overcome the disadvantages of being “tokens”—they can create alliances, for instance—but that, above 35%, they become a “potential subgroup” (26). We do know that, where sex ratios are highly skewed (below 15% women, or above 85%), gender salience is high and so is harassment (27, 28). Cohen, Broschak, and Haveman find that increases in women in upper management improve matters for women in lower and middle management up to a point; the peak is about 25%, at the midpoint of Kanter’s range (29). Thus, increases in women managers, up to about 25%, may improve harassment program effects.

Do all groups of women activate group threat? Research on intersectionality suggests that perceived threat may depend on a group’s location in the race/gender hierarchy. White women carry one dominant status (white) and one subordinate status (female). Minority women carry two subordinate statuses, and, in certain contexts, they elicit less backlash for dominant behavior than white women do (30, 31). Moreover, white women hold more management jobs than any other group of women, and their sheer numbers may activate threat (26). Thus, we expect group threat to affect white women more than black, Hispanic, or Asian-American women.

In sum, we expect positive effects of manager training and negative effects of grievance procedures and employee training. We do not expect the negative effects to simply wipe out the positive effects, because these effects are conditional on women in management, and thus these effects should appear in different workplaces. Higher numbers of women managers should catalyze positive effects of manager training and prevent adverse effects of grievance procedures and employee training. This should hold for the three groups of minority women, because they are less likely to activate group threat. However, for white women, group threat should reverse this pattern—higher numbers of women managers should prevent the positive effects of manager training and activate the negative effects of grievance procedures and employee training.

Data and Methods

We assess effects of the introduction of harassment grievance and training programs on women in management by combining data from two sources, a retrospective survey of corporate policies and programs and an annual demographic census of employers. Data cover the period in which employer harassment programs spread (1971–2002), which makes it possible to estimate the effects of program adoption (32). This was before the widespread use of online training.

Data on establishment harassment programs, and other management practices and policies, come from our own retrospective survey, administered by the Princeton Survey Research Center in 2002. The survey provides time-varying information for a national sample of 805 private sector employers. Princeton’s Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects approved the research protocol (the authors were, respectively, Professor of Sociology and doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at Princeton at the time). Each respondent received a letter covering the purpose of the study; the topics to be covered; and the names, addresses, and phone numbers of the principal investigator and Survey Research Center. The letter explained that participation was voluntary and could be terminated at any time, and that all data would remain confidential. Phone interviewers asked for verbal consent to participate before starting the interview. The survey covered organizational practices—no personal information was collected.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s (EEOC) annual census of private sector workplaces with more than 100 workers provides gender, race, and ethnic composition for surveyed workplaces by occupational category (33). The EEOC data are confidential, by statute, but the EEOC makes them available to academic scientists through Intergovernmental Personnel Agreements. Time series data on external labor market characteristics come from Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) surveys. Our Stata code and the blinded survey data are available through Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. We will provide the key for matching establishments with the EEOC’s workforce data to researchers with access to those data.

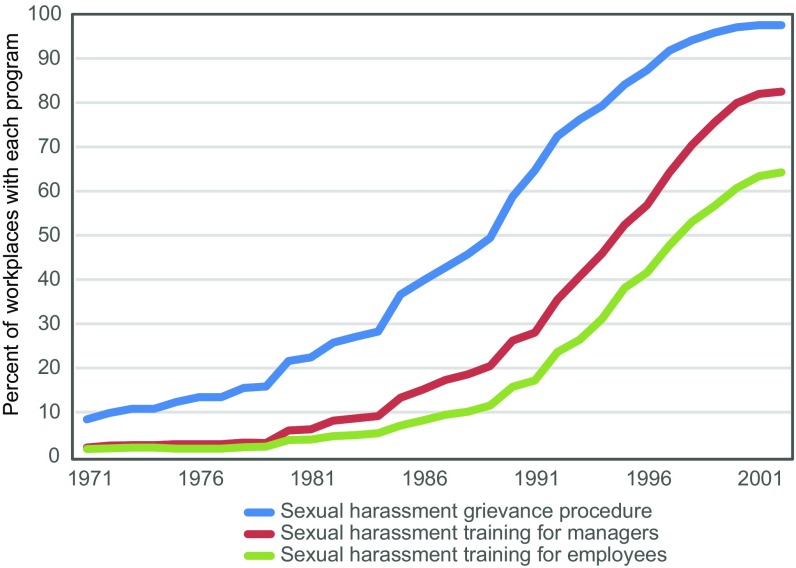

Fig. 1 reports the prevalence of sexual harassment grievance procedures, sexual harassment training for managers, and sexual harassment training for employees for the 805 employers in our analysis. By 2002, 98% of employers had grievance procedures, 82% had training for managers, and 64% had training for employees. Only 18% of the observations (workplace years) have all three practices, permitting us to disentangle their effects.

Fig. 1.

Percent of workplaces with sexual harassment grievance procedures, training for managers, and training for employees. Maximum n = 805. The figure is based on employer years included in the analysis. Not all workplaces are represented in each year because 1) some workplaces were established during the period and 2) some crossed the EEOC reporting thresholds (100 workers, or 50 workers for federal contractors).

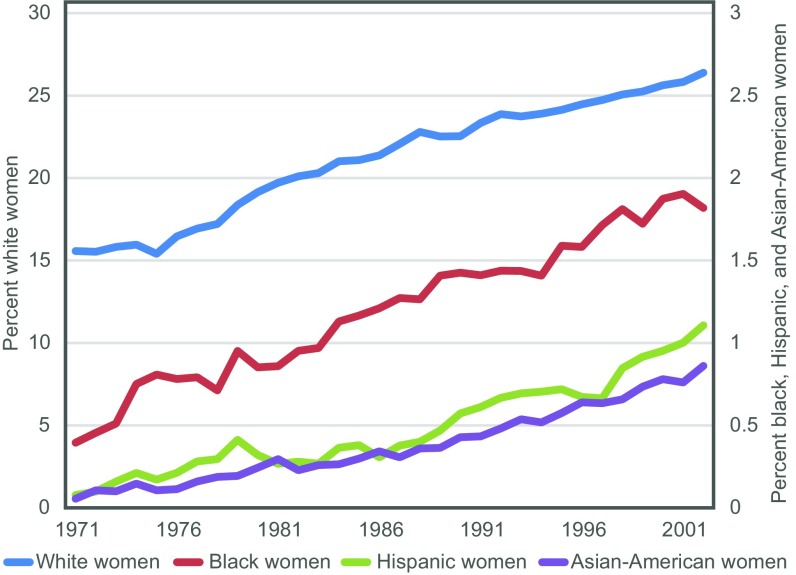

Fig. 2 reports change over time in the representation of each group of women in management jobs in the sample of 805 employers. In the average sampled workplace, white women made up 15% of managers in 1971 and 26% in 2002. Black women rose from 0.4 to 1.8%; Hispanic women rose from 0.1 to 1.1%; and Asian-American women rose from 0.1 to 0.9%. These figures understate national gains for women in management because the sample excludes several groups of employers that saw greater gains in women on average, including newly established firms and public sector workplaces.

Fig. 2.

Average percent of women managers, by race and ethnicity, among the 805 sampled workplaces. Data come from the EEOC’s annual workforce census, the EEO1 survey. The figure is based on employer years included in the analysis. See Fig. 1 note for inclusion criteria.

We examine changes in the share (log odds) of white, black, Hispanic, and Asian-American women in management following the adoption of sexual harassment grievance procedures, training programs for managers, and training programs for employees. Coefficients estimate the average effects of new programs across all of the postadoption years that we observe. The number of years observed depends on when an employer adopted. For each program, we have an average of a least 7 y of postadoption data (Fig. 1). We report panel data models with fixed effects and robust SEs (see SI Appendix for a detailed methodological discussion). The fixed-effects specification accounts for organizational features that do not vary over time, such as industry. In the models, we control for a host of human resources, diversity, work−life, and general harassment policies and programs, as well as for demographic characteristics of the focal workplace and of the state and the industry workforces. To capture environmental changes not covered by variables in the models, we include a time trend, interacted with both state and (two-digit) industry (see SI Appendix for full models).

Results

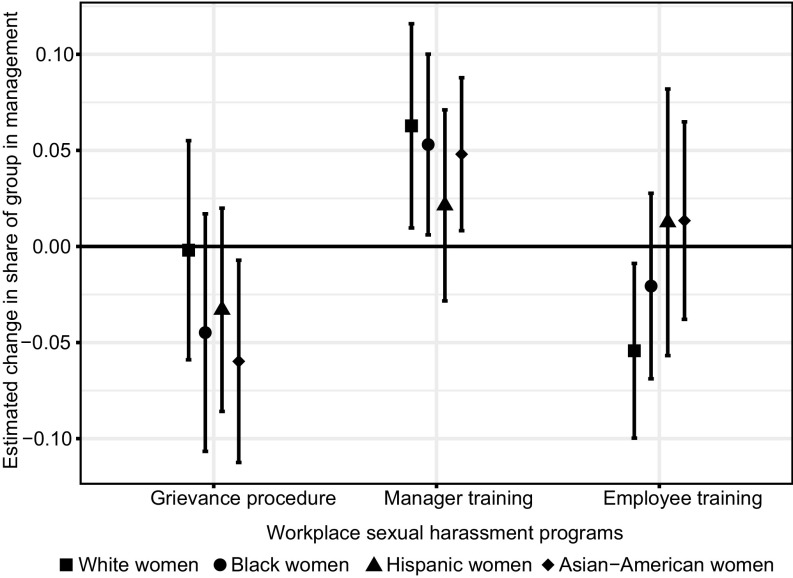

Results are presented in Figs. 3–6. Fig. 3 shows average change in the share of each group in management, over the years each program was in place, for workplaces that created grievance procedures, manager training, and employee training. The bars represent 95% confidence intervals around the point estimates. Following the creation of sexual harassment grievance procedures, the share of Asian-American women in management declines. Coefficients for other groups are not statistically significant—confidence intervals cross the 0 threshold. Sexual harassment training programs for managers are followed by significant increases in white, black, and Asian-American women in management. Sexual harassment training programs for employees are followed by significant reductions in white women in management. While these results are broadly consistent with predictions, if program effects are moderated by women in management, as we predict, the noninteracted effects tell only part of the story.

Fig. 3.

Estimated changes in the share of white and minority women in management following the adoption of sexual harassment grievance procedures, manager training, and employee training. Values on the vertical axis represent change in the log odds of the group in management. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown.

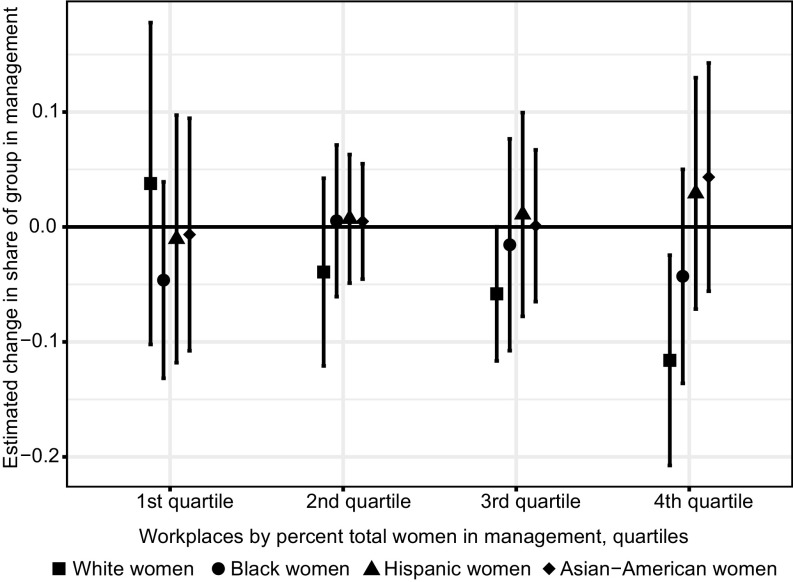

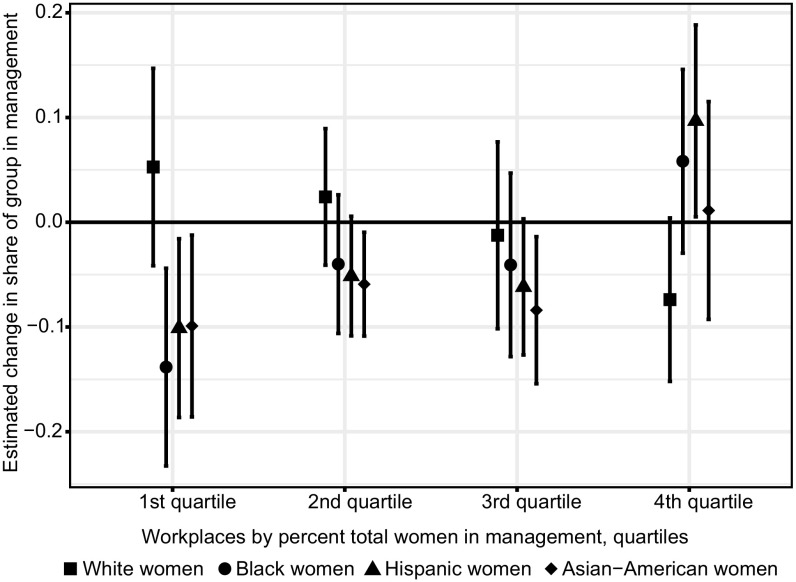

Fig. 6.

Estimated changes in the share of white and minority women in management following the adoption of employee sexual harassment training, for workplaces in the first, second, third, and fourth quartiles of total women in management. Values on the vertical axis represent change in the log odds of the group in management. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown.

To assess how harassment program effects are moderated by women managers, we interact program variables with binary variables representing the second, third, and fourth quartiles of total women in management. The first quartile has observations with 0 to 6.7% women managers; the second, 6.7 to 16.7%; the third, 16.7 to 37.5%; and the fourth, 37.5 to 100%.

In Fig. 4, we report the point estimates for changes in the share of white and minority women in management following the introduction of sexual harassment grievance procedures in workplaces at different quartiles of women in management. We show noninteracted program coefficients for workplaces in the first quartile of total women managers. For those in the other quartiles, we report the linear combinations of the program coefficients and the program × quartile interaction coefficients (as described in SI Appendix).

Fig. 4.

Estimated changes in the share of white and minority women in management following the adoption of sexual harassment grievance procedures, for workplaces in the first, second, third, and fourth quartiles of total women in management. Values on the vertical axis represent change in the log odds of the group in management. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown.

For white women, effects of sexual harassment grievance procedures are negative and marginally significant (P < 0.10) among workplaces in the fourth quartile of women managers. This is consistent with the group threat thesis. For all three groups of minority women, grievance procedures show significant negative effects in workplaces with few women managers—those in the first quartile. These negative effects decline as women in management rise. For black and Hispanic women, the negative effects disappear after the first quartile, and, for Hispanic women, the effect turns positive in the fourth quartile. For Asian-American women, negative effects persist through the third quartile.

Management allies, then, appear to help minority women. Where men dominate, grievance procedures make matters worse for all three minority groups. However, where women hold more management jobs (the fourth quartile begins at 37.5%), negative effects disappear for black and Asian-American women, and positive effects appear for Hispanic women.

In Fig. 5, we present the estimates of changes following the creation of sexual harassment training programs for managers, by each quartile of total women in management. For white women, manager training shows positive effects in workplaces with few women in management that decline in the higher quartiles. Positive effects are significant among workplaces in the first two quartiles of total women managers (P < 0.05). This lends support to our predictions that 1) manager training will reduce harassment but, 2) at high levels of women in management, harassment programs catalyze group threat.

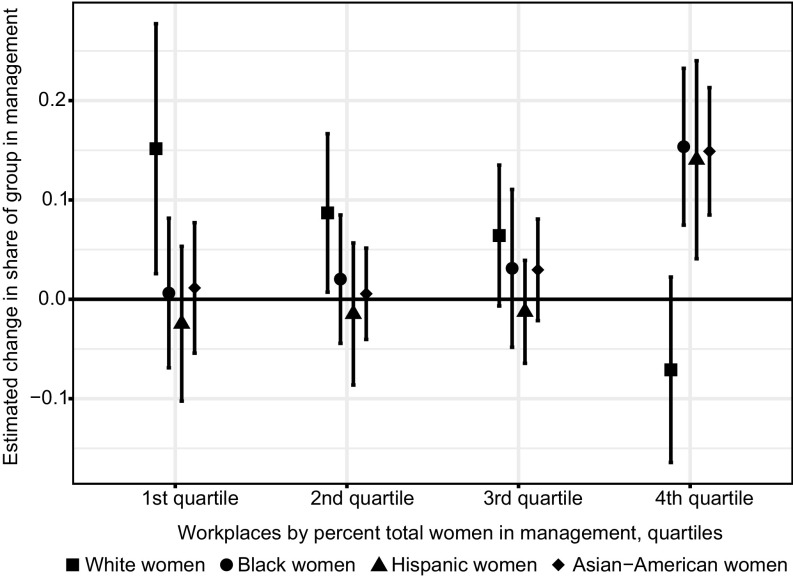

Fig. 5.

Estimated changes in the share of white and minority women in management following the adoption of sexual harassment training for managers, for workplaces in the first, second, third, and fourth quartiles of total women in management. Values on the vertical axis represent change in the log odds of the group in management. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown.

For black, Hispanic, and Asian-American women, training shows significant positive effects only in workplaces in the fourth quartile of women in management. This finding is consistent with our prediction that, for groups of women least likely to activate group threat, according to the intersectionality literature, manager training is most effective in organizations with large contingents of women managers, because women are less likely to respond negatively to training than men.

We consider an alternative mechanism—that manager training signals that employers favor equality and thereby increases manager commitment to hiring and promoting women (34). If that were the main mechanism, we would expect manager diversity training to show the same effect as harassment training. It does not (see “diversity training” in full models in SI Appendix).

It might be that we do not observe positive effects for white women among workplaces in the fourth quartile because there is no room for white women to grow. However, few workplaces in the fourth quartile have reached the limit—0.37% of observations have 100% women managers. Thus, in Fig. 5, we find the predicted positive effects in the fourth quartile for the three minority groups. In any event, the noninteracted coefficient for the fourth quartile should pick up any limits on further growth, and the interaction should pick up the unique effect of women in management in the presence of manager training (full results reported in SI Appendix). Note that linear interactions between total women managers and all three harassment programs produced significant negative coefficients for white women (SI Appendix).

Manager training shows the greatest promise of the three programs we examine. In the average workplace in the first quartile of total women managers, manager training is followed by an estimated 16% increase in white women in management. For black, Hispanic, and Asian-American women in workplaces in the fourth quartile of women managers (more than 37.5%), manager training is followed an estimated 14 to 16% increase in each group.

Sexual harassment training for employees, which typically relies on forbidden-behavior curriculum, shows none of the positive effects that training for managers shows. This is consistent with research finding that, while such training can improve knowledge about harassment, it can exacerbate gender role hostility and propensity to harass among men. In Fig. 3, without quartile interactions, we saw a negative effect of employee training on white women in management. In Fig. 5, we see that employee training is followed by reductions in white women managers in workplaces where women hold the most management jobs. Employee sexual harassment training in workplaces with more women managers appears to trigger backlash against white women.

Can manager training improve the effects of grievance procedures? We tested this possibility by interacting grievance procedure with manager training and found no effect. Nor did we find an effect when interacting grievance procedure with employee training (SI Appendix). It does not appear that either kind of training improves grievance procedure effects.

Conclusion

Sexual harassment remains a cancer on the workplace despite the widespread adoption of grievance procedures, manager training, and employee training. Figuring out whether these programs actually reduce harassment, and whether they can be tweaked to work better, should be a priority. To that end, we build on a long tradition of research in psychology and sociology that has, as yet, had little impact on employer practice. We ask, in particular, whether harassment programs make workplaces more hospitable to women, increasing their numbers in management.

Previous studies suggest that grievance procedures may backfire, that manager training may help, and that employee training is unlikely to do much. First, surveys show that people who file grievances frequently face retaliation and rarely see their harassers fired or reassigned. We find that new grievance procedures are not followed by increases in white women in management, and are followed by reductions in black, Hispanic, and Asian-American women. Second, field research on the type of training that best approximates manager training—bystander intervention training—suggests that it increases the intention to intervene, confidence about intervening, and actual intervention. We find that new manager training programs are followed by increases in white, black, Hispanic, and Asian-American women in management. Third, field and laboratory studies of training for employees, typically with forbidden-behavior curriculum, show some positive effects on men’s knowledge about harassment, but also some adverse effects—increasing victim blaming and likelihood of harassing. We find that new employee training programs are followed by reductions in white women in management.

Research also suggests that these programs will be more effective in workplaces with more women managers—women are more likely to believe harassment complaints and less likely to react negatively to training. We find that, for minority women, women managers improve the effects of grievance procedures and manager training. However, research also shows that, when women’s gains in management threaten men’s dominance, group threat can lead men to resist efforts to accommodate women. White women are most likely to activate group threat, and not only because of their numbers in management. Intersectionality studies also show that dominance by white women more often elicits backlash than dominance by minority women. We find that, for white women, positive effects of manager training disappear, and negative effects of grievance procedures and employee training appear, in workplaces with the most women managers. In further analyses, we found that growth in women managers up to about 12% improved harassment program effects for white women, but growth beyond that did not (see decile analysis results and full discussion in SI Appendix) (26, 29).

Taken together, the findings indicate that the positive effects of manager training are not counteracted by the negative effects of grievance procedures or employee training, because the effects appear in different sorts of workplaces. For all three groups of minority women, in workplaces with more women managers, manager training helps; in workplaces with fewer women managers, grievance procedures hurt. For white women, in workplaces with more women managers, grievance procedures and employee training hurt; in workplaces with fewer women managers, manager training helps. It appears that harassment programs have made things worse for certain groups of women in certain workplaces, and better for other groups of women in other workplaces.

The findings hold implications for employers, pointing to both problematic and promising program features. They reinforce victim surveys suggesting that grievance procedures incite retaliation and rarely satisfy victims. Even in workplaces with manager training, which is generally effective, grievance procedures do no good. How might employers improve complaint handling? On surveying the research, the EEOC’s Select Taskforce on the Study of Harassment in the Workplace recommended that employers offer alternative complaint systems less likely to blow back on victims, such as independent ombudspersons who can hear complaints confidentially and talk through victims’ options (35, 36). Tech start-ups have devised their own alternatives, including virtual ombudspersons and reporting systems. Online reporting may address a common #MeToo and #WhyIDidn’tReport criticism—employer confidentiality clauses prevent victims from learning that their harasser has done it before. Online, victims can report harassment when they choose to but embargo reports until others complain about the same harasser.

The findings point to the promise of harassment training that treats trainees as allies rather than as potential perpetrators. Our comparison of manager and employee training is key here. Manager training, like bystander intervention training, gives trainees the tools to recognize and address harassment. It has the broadest positive effects. By contrast, employee training, which most often uses legalistic forbidden-behavior curriculum, shows null or adverse effects. Training is where the lion’s share of the corporate antiharassment budget goes. Employers might do better to offer bystander training to everyone. In studies on college campuses and in the military, this approach has been shown to increase the intention to intervene and self-reported interventions among college students and enlisted men (13, 15). Bystander training may offer the best hope for avoiding the demonstrated adverse effects of forbidden-behavior training.

The analyses point to the promise of putting more women in management, and many firms have replaced men felled by #MeToo with women. However, men still dominate the middle and upper echelons. As long as managers at the top come from the middle, change may be slow. For now, employers might consider research suggesting that male managers with the right attitudes can, like women managers generally, improve program effects. The US Armed Forces implemented a multipronged strategy to fight sexual harassment and assault. Women who reported that their unit leaders made an “honest and reasonable effort to stop harassment” found both grievance handling and harassment training to be more effective. Those women also reported reductions in personal experiences of harassment and in overall workplace harassment (37). That study, in a context where virtually all leaders are men, suggests that leaders with the right stuff can prevent harassment programs from backfiring. Employers might select managers for promotion up the ranks, be they men or women, who have proven records as allies to harassment victims.

The findings don’t suggest a clear path to countering group threat. Where women have made inroads in management, all three programs appear to incite backlash against the group of women whose dominance most threatens men: white women. In workplaces in the top quartile of total women managers, backlash wipes out positive program effects or creates negative effects. Again, management allies may be the key. Perhaps selecting male managers who will believe harassment victims and respond positively to training will help, because these may be the very men who won’t react negatively to group threat. However, we clearly need more research on group threat and how to prevent it. Women in leadership could spark a virtuous cycle, in which women leaders make harassment programs more effective, and effective programs help employers to retain and promote women. However, that virtuous cycle may never get underway in the face of group threat.

The lessons we draw from the corporate world hold implications for harassment programs in academia, which is second only to the military in rates of harassment. A 2018 National Academies of Sciences report on harassment suggests that the problems with corporate sexual harassment grievance procedures and training are mirrored in the academy (38). There, as in the corporate world, women rarely file grievances, because they distrust procedures and fear retaliation. There, as in the corporate world, training can backfire, leading to backlash among men. While it may not be surprising that the corporate world has not built sexual harassment programs on the knowledge base that academia has produced, it is surprising that academia itself has not done so.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Science Foundation for funding. We thank Bliss Cartwright and Ron Edwards of the EEOC for making the EEO-1 data available through an Intergovernmental Personnel Agreement. We thank Joshua Guetzkow, Carly Knight, and Daniel Schrage for suggestions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Our Stata code and the blinded survey data have been deposited in the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) database, http://doi.org/10.3886/E109781V3.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1818477116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dobbin F., Kelly E., How to stop harassment: The professional construction of legal compliance in organizations. Am. J. Sociol. 112, 1203–1243 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Leary-Kelly A. M., Bowes-Sperry L., Bates C. A., Lean E. R., Sexual harassment at work: A decade (plus) of progress. J. Manage. 35, 503–536 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antecol H., Cobb-Clark D., Does sexual harassment training change attitudes? A view from the federal level. Soc. Sci. Q. 84, 826–842 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nye C. D., Brummel B. J., Drasgow F., Too good to be true? Understanding change in organizational outcomes. J. Manage. 36, 1555–1577 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Merit Systems Protection Board , Sexual Harassment in the Federal Workplace: Is It a Problem? (US Merit Systems Protection Board, Washington, DC, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Merit Systems Protection Board , Sexual Harassment in the Federal Government: An Update (US Merit Systems Protection Board, Washington, DC, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Merit Systems Protection Board , Sexual Harassment in the Federal Workplace: Trends, Progress, Continuing Challenges (US Merit Systems Protection Board, Washington, DC, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLaughlin H., Uggen C., Blackstone A., The economic and career effects of sexual harassment on working women. Gend. Soc. 31, 333–358 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortina L. M., Berdahl J. L., “Sexual harrassment in organizations: A decade of research in review” in The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Behavior, Barling J., Cooper C. L., Eds. (Sage, Los Angeles, 2008), vol. 1, pp. 469–497. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bastian L. D., Lancaster A. R., Reyst H. E., 1995 Sexual Harrassment Survey (US Department of Defense, Arlington, VA, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cortina L. M., Magley V. J., Raising voice, risking retaliation: Events following interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 8, 247–265 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith A., Sexual Harassment Training Should Be Separate for Managers and Rank and File (Society for Human Resource Management, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz J., Moore J., Bystander education training for campus sexual assault prevention: An initial meta-analysis. Violence Vict. 28, 1054–1067 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cares A. C., et al. , Changing attitudes about being a bystander to violence: Translating an in-person sexual violence prevention program to a new campus. Violence Against Women 21, 165–187 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potter S. J., Moynihan M. M., Bringing in the bystander in-person prevention program to a U.S. military installation: Results from a pilot study. Mil. Med. 176, 870–875 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bisom-Rapp S., An ounce of prevention is a poor substitute for a pound of cure: Confronting the developing jurisprudence of education and prevention in employment discrimination law. Berkeley J. Employ. Labor Law 22, 1–46 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magley V. J., Fitzgerald L. F., Salisbury J., Drasgow F., Zickar M. J., “Changing sexual harassment within organizations via training interventions: Suggestions and empirical data” in The Fulfilling Workplace: The Organization's Role in Achieving Individual and Organizational Health, Burke R., Cooper C. Eds. (Gower, Surrey, United Kingdom, 2013), pp. 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bingham S. G., Scherer L. L., The unexpected effects of a sexual harassment educational program. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 37, 125–153 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearney L. K., Rochlen A. B., King E. B., Male gender role conflict, sexual harassment tolerance, and the efficacy of a psychoeducative training program. Psychol. Men Masc. 5, 72–82 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robb L. A., Doverspike D., Self-reported proclivity to harass as a moderator of the effectiveness of sexual harassment-prevention training. Psychol. Rep. 88, 85–88 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh B. M., Bauerle T. J., Magley V. J., Individual and contextual inhibitors of sexual harassment training motivation. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 24, 215–237 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lonsway K. A., Cortina L. M., Magley V. J., Sexual harassment mythology: Definition, conceptualization, and measurement. Sex Roles 58, 599–615 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald P. Workplace sexual harassment 30 years on: A review of the literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 14, 1–17 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tinkler J., Gremillion S., Arthurs K., Perceptions of legitimacy: The sex of the legal messenger and reactions to sexual harassment training. Law Soc. Inq. 40, 152–174 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blalock H., Towards a Theory of Minority Group Relations (Wiley, New York, 1967). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanter R. M., Men and Women of the Corporation (Basic Books, New York, NY, 1977). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welsh S., Gender and sexual harassment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 25, 169–190 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roscigno V., The Face of Discrimination: How Race and Gender Impact Work and Home Lives (Rowman and Littlefield, New York, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen L. E., Broschak J. P., Haveman H. A., And then there were more? The effect of organizational sex composition on the hiring and promoting of managers. Am. Sociol. Rev. 63, 711–727 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livingston R. W., Rosette A. S., Washington E. F., Can an agentic black woman get ahead? The impact of race and interpersonal dominance on perceptions of female leaders. Psychol. Sci. 23, 354–358 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ridgeway C. L., Kricheli-Katz T., Intersecting cultural beliefs in social relations: Gender, race, and class binds and freedoms. Gend. Soc. 27, 294–318 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalev A., Dobbin F., Workplace Sexual Harassment Survey, 1971-2002. Replication Dataset. 10.3886/E109781V3. Deposited 15 May 2019. [DOI]

- 33.Robinson C., Taylor T., Tomaskovic-Devey D., Zimmer C., Irvine M. W., Studying race/ethnic and sex segregation at the establishment-level: Methodological issues and substantive opportunities using EEO-1 reports. Work Occup. 32, 5–38 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edelman L. B., Working Law: Courts, Corporations, and Symbolic Civil Rights (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowe M. P., Baker M., Are you hearing enough employee concerns? Harv. Bus. Rev. 62, 127–138 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feldblum C. R., Lipnic V. A.; USEEO Commission, Select Task Force on the Study of Harassment in the Workplace: Report of Co-Chairs Chai R. Feldblum & Victoria A. Lipnic (US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Washington, DC, 2016).

- 37.Buchanan N. T., Settles I. H., Hall A. T., O’Connor R. C., A review of organizational strategies for reducing sexual harassment: Insights from the U. S. military. J. Soc. Issues 70, 687–702 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine , Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2018). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.