Abstract

In the healthy lung, bronchi are tethered open by the surrounding parenchyma; for a uniform distribution of these peribronchial structures, the solution is well known. An open question remains regarding the effect of a distributed set of collapsed alveoli, as can occur in disease. Here, we address this question by developing and analyzing microscale finite-element models of systems of heterogeneously inflated alveoli to determine the range and extent of parenchymal tethering effects on a neighboring collapsible airway. This analysis demonstrates that micromechanical stresses extend over a range of ∼5 airway radii, and this behavior is dictated primarily by the fraction, not distribution, of collapsed alveoli in that region. A mesoscale analysis of the microscale data identifies an effective shear modulus, Geff, that accurately characterizes the parenchymal support as a function of the average transpulmonary pressure of the surrounding alveoli. We demonstrate the use of this formulation by analyzing a simple model of a single collapsible airway surrounded by heterogeneously inflated alveoli (a “pig-in-a-blanket” model), which quantitatively demonstrates the increased parenchymal compliance and reduction in airway caliber that occurs with decreased parenchymal support from hypoinflated obstructed alveoli. This study provides a building block from which models of an entire lung can be developed in a computationally tenable manner that would simulate heterogeneous pulmonary mechanical interdependence. Such multiscale models could provide fundamental insight toward the development of protective ventilation strategies to reduce the incidence or severity of ventilator-induced lung injury.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY A destabilized lung leads to airway and alveolar collapse that can result in catastrophic pulmonary failure. This study elucidates the micromechanical effects of alveolar collapse and determines its range of influence on neighboring collapsible airways. A mesoscale analysis reveals a master relationship that can that can be used in a computationally efficient manner to quantitatively model alveolar mechanical heterogeneity that exists in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which predisposes the lung to volutrauma and/or atelectrauma. This analysis may lead to computationally tenable simulations of heterogeneous organ-level mechanical interactions that can illuminate novel protective ventilation strategies to reduce ventilator-induced lung injury.

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, mechanical ventilation, parenchymal tethering, reduced-dimension model, shear modulus

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian lung is an extraordinary example of a physiological organ whose function depends upon microfluidic principles. Despite its high mechanical compliance, the healthy lung is remarkably stable because of two interdependent mechanical processes: 1) mechanical interdependency that exists between the alveoli and airways, with the alveoli functioning as a foam-like structure that provides parenchymal tethering support of compliant airways; and 2) pulmonary surfactant physicochemical properties that reduce and dynamically modify the lining fluid surface tension during respiration. This stabilizes the lung by modifying the elastic recoil as a function of the history of interfacial expansion/compression (18) and counteracts the interfacial instabilities that can lead to airway and alveolar obstructions that would reduce gas exchange.

These two effects are linked, because surface tension modulates parenchymal tethering and can influence airway stability from fluid-structure interactions related to the Plateau-Rayleigh instability (9–11, 14, 15). This, in turn, can detrimentally affect gas flow to the subtended alveoli, further reducing parenchymal tethering with potentially devastating effects. These are prime examples of multiscale interactions that span from the molecular scale (surfactant) to sub-submillimeter scale (single- and multicellular) to millimeter scale (alveolar) mechanical interactions. Thus, small-scale interactions function in concert to stabilize the large-scale organ.

Parenchymal tethering plays a crucial role in maintaining airway patency (17, 25, 31). Lai-Fook et al. (19) investigated the mechanical interdependcaency between bronchial pressure-volume behavior and the parenchyma shear modulus (G) as a function of the transpulmonary pressure (PTP) in a uniformly inflated lung. That study demonstrates that increasing the lung volume significantly increases the peribronchial stress, which helps to sustain airway patency and stabilize the lung. Positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) ventilation is a useful protocol that takes advantage of this principle to maintain lung stability.

Unfortunately, in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pulmonary stability can break down. Liquid obstruction of airways impairs gas exchange and results in heterogeneous ventilation. Ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) can occur from either overdistension (volutrauma) or repetitive closing and reopening of compliant airways and alveoli (atelectrauma) (12), although recent studies indicate that atelectrauma predisposes the lung to volutrauma (13).

Venegas et al. (29) developed a network model of airway-parenchyma interactions that suggests that the progression of poorly ventilated regions increases catastrophically if local tethering is heterogeneous. Clearly then, heterogeneous tethering should be included in any multiscale lung model if one intends to simulate the abnormal pulmonary mechanical phenomena associated with ARDS. Organ-level models that could investigate the full repertoire of pathophysiological microscale (alveolar level) and macroscale (lobular and full organ) interactions would require computations of the interactions of >108 alveoli and associated airways in a three-dimensional (3D) compliant structure with heterogeneity due to lung geometry, gravity, tissue properties, and disease progression. This approach is simply untenable with today’s computing environments; nevertheless, if possible, these simulations could forecast protective modes of ventilation that could reduce VILI.

While a complete organ-level multiscale model of the lung is not feasible, we hypothesize that it is possible to develop insight from microscale models that, with appropriate volume averaging, can reveal mesoscale properties that can create the link between small- and large-scale structures. At the microscale, Denny and Schroter (3) and Fujioka et al. (6) developed finite-element models (FEM) of connected, compartmentalized alveoli to elucidate the mechanical properties of lung parenchyma under a variety of mechanical loading scenarios. We seek to extend these models to the mesoscale, which reflects the parenchymal tethering effects relevant to an airway. This is an important step in creating multiscale models of the entire lung.

Therefore, in the present study, we explore FEM models associated with obstructed and unobstructed alveoli in the neighborhood of a compliant airway to establish the mechanical properties that affect the peribronchial stress that influence airway stability under pathophysiological conditions. We use this highly detailed microscale FEM model to provide data from which we establish an equivalent mesoscale continuum mechanics construct, the effective shear modulus (Geff) that can faithfully represent the influence of heterogeneously obstructed alveoli, and their effect on parenchymal tethering of compliant pulmonary airways. This goal is a critical step toward the development of a computationally tractable multiscale model of the full lung that uses first principles to simulate pulmonary mechanical interactions.

Conceptual Framework

Parenchyma is modeled by a 3D network of interacting microscale alveoli surrounding an airway. The alveolar model is based on the work of Fujioka et al. (6) and is simulated using high-performance computing (HPC) approaches, from which the physical relationships are derived following Fujioka et al. (7). We focus on identifying parenchymal tethering effects of nonuniformly recruited alveoli surrounding a small compliant airway, since these interactions influence organ-level behavior. We seek to re-express key results in a reduced-dimension parametric formulation that is deduced from a rational mechanics analysis of the mesoscale system. If successful, such a formulation could be used to accurately simulate the complex mechanical interactions within the lung using a strategy following Ryans et al. (27).

To establish the reduced-dimension empirical relationships, we utilize FEM models to investigate the mechanical relationship between the airway and its surrounding parenchyma. We then define the equivalent interactions in a continuum mechanics framework, from which we estimate Geff. For instance, consider the scenario illustrated in Fig. 1, where an airway obstruction results in the presence of obstructed (red) alveoli, with other patent pathways leading to aerated (blue) alveoli surrounding an airway.

Fig. 1.

Representative illustration of airway obstruction resulting in the presence of aerated (blue) and obstructed (red) alveoli surrounding separate conducting airways. Geff, effective shear modulus; Pyield, critical pressure drop.

We assume that the obstructed alveoli are air-filled but remain inflated with a pressure, POBS, that deviates from aerated alveoli, (PALV)open. POBS ≠ (PALV)open because the obstruction acts as a pressure relief valve due to a yield/pressure phenomenon wherein the liquid blockage moves only if a critical pressure drop (Pyield) is exceeded (8, 25, 31). In the analysis that follows, we assume that Pyield = 8γ/R = 4 cmH2O, as would be appropriate for the closure of a 1-mm diameter airway with surface tension γ = 25 mN/m.

We investigate systems with either 1) hypoinflated obstructed alveoli [POBS = (PALV)open − Pyield] that would occur when airway closure occurs at end-expiration (if the obstructed alveolus were to experience a lower pressure, the obstruction would move centrally, equilibrating the pressure at POBS =Pyield) and 2) hyperinflated obstructed alveoli [POBS = (PALV)open + Pyield] that can occur due to the elastic recoil of the obstructed alveolus, leading to an increase in the gas pressure within the obstructed alveolus (if the obstructed alveolus were to experience a higher pressure, the obstruction would move distally, equilibrating the pressure at POBS = Pyield).

In all cases we assume that the obstructed alveolus remains gas filled from tethering effects of neighboring alveoli and neglect absorption atelectasis. We note that the terms hypoinflated and hyperinflated are relative to nonobstructed alveoli, irrespective of the current lung volume. For this reason, even with low lung inflation, it is possible to have hyperinflated alveoli relative to other nonobstructed alveoli.

The cross-sectional view in Fig. 1 represents the distribution of aerated and obstructed alveoli surrounding the airway; this distribution results in regions with significantly different alveolar pressures that can heterogeneously influence airway tethering. From this discrete representation, we seek a continuum model that can represent the relationship between the peribronchial pressure exerted on the airway by the parenchyma and the inflation states of the alveoli. To do so, we seek to establish the relationship between the effective shear modulus (Geff) defined in Eq. 1 below, and the alveolar pressure distribution.

Clearly, many permutations of the heterogeneous alveolar distribution exist, and it is not feasible to create a model to account for every scenario. In lieu of that, we investigate statistical variations of this distribution (Fig. 2) by assuming that obstructed alveoli are randomly dispersed within the parenchyma while retaining the ratio of obstructed/unobstructed alveoli (the “sprinkled donut” model).

Fig. 2.

Approximation of heterogeneous tethering using a uniformly random distribution of obstructed alveoli (“sprinkled donut”).

Computational experiments are conducted with these random distributions to identify the relationships between Geff of the parenchyma, the percentage of impaired alveoli present, and the sensitivity of Geff to the distribution of collapsed alveoli. We seek to answer two questions. 1) What region of influence surrounding the airway (RROI) determines the relevant effective shear modulus of the surrounding parenchyma, and 2) is the effective shear modulus with a uniform random distribution of closed alveoli equivalent mechanically to the effective shear modulus with localized regions of closure if the same fractions of alveoli are collapsed?

If we can identify a suitable RROI, and if we find that Geff is only a function of the fraction of collapsed alveoli (insensitive to the distribution), we can then be confident that an empirical relationship of this mesoscale representation of the parenchymal mechanics can provide the foundation for a reduced-dimension model that can be efficiently implemented to model airway/parenchymal interactions in the entire lung.

METHODS

The Finite-Element Model

We investigated an annular region of parenchyma surrounding a cylindrical “hole,” following the work of Lai-Fook et al. (20) This investigation will elucidate the mechanical properties of the parenchyma alone, and further analysis (see discussion) will incorporate these results into the peri-airway pressure component of the transmural pressure for a compliant airway.

Our analysis is based upon a finite-element model (FEM) that was developed to establish the relationship between the effective shear modulus (Geff) of parenchyma surrounding an airway and the transpulmonary pressures of the corresponding alveoli (6). In that model, the lung parenchyma comprises individual alveolar chambers modeled by truncated octahedrons. This displacement-based FEM model is utilized to analyze the deformations of the alveolar system as a function of the pressure in each alveolus, the outer pressure, and the fiber-constitutive relationships.

Each face consists of septal border fiber bundles that lie on the perimeter of the face and cross-linking fiber bundles that lie across the face. Each alveolus sustains the force balance through elastin and collagen fibers arranged on the alveolar membrane; these membranes are under tension from neighboring elements and a pressure-difference across the membrane, providing a normal stress on the membrane. A thin surfactant-laden liquid layer exists in the alveolus where the surface tension (γ) is a function of the interfacial surfactant concentration (Γ).

To model the effect of surface tension, we consider a sphere of the same volume as the truncated octahedron model of the alveolus (see Fig. 2), Valv, and define the radius of the equivalent sphere to be Ralv = (3Valv/4π)1/3. The pressure jump across the liquid lining is assumed to be ΔP = 2γ/Ralv. Assuming a uniform surfactant concentration, Γ = MALV/SALV, where MALV is the mass of surfactant and SALV the surface area of an alveolus. A linear equation of state is used to calculate γ(Γ), with MALV and the slope of the equation of state determined such that γ = 30 dyn/cm at TLC and γ = 5 dyn/cm at TLC/3.

The boundary conditions for the FEM annulus surrounding the parenchymal hole allow the alveolar elements to expand and contract freely. This is accomplished by defining the stresses at the faces of the domain as illustrated in Fig. 3, where the boundaries support zero tangential stresses. Each face has a normal stress/strain conditions where the fixed face (red) of the annulus restricts movement in the positive z-direction (uz = 0) along the cylindrical face (blue), the normal stress is the negative of the surrounding pleural pressure (τrr = −PPL), and the opposing free-moving face (green) has normal stress (τzz = −PPL). The hole is external to the domain of the finite-element model and provides stress to the parenchyma through application of PPA (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Boundary conditions of finite-element model (FEM) on the fixed face (red), cylindrical face (blue), and free-moving face (green). The interior hole is assumed to be at a constant pressure (PPA), as shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

A: parenchyma in equilibrium uniform stressed state. B: change in hole lumen with change in peri-airway pressure (PPA) from the uniform stress condition pleural pressure (PPL).

Simulations proceed to mechanical equilibrium at the microscale by varying the nodal positions until ΣδF < 10−5dyn at each node, where δF = Fp − Ff, with Fp representing the equivalent vertex forces due to the pressures and Ff the forces that resulted from the extension of fibers.

We investigated perturbations from this state to identify mesoscale characteristics (Geff) that describe the mechanical features of nonuniformly inflated alveoli as a function of the mean transpulmonary pressure following Wilson (30). Deformations are computed for the parenchyma, as alveolar pressures are modified to represent inflation, deflation, or upstream closure. As we will show below, perturbations of the peri-airway pressure (PPA) induce modifications of a parenchymal hole lumen cross-sectional area, and this deformation provides the data necessary to identify Geff. We use this process to calculate Geff from both localized and random distributions of obstructed alveoli.

Model Mechanics

Model mechanics are driven by the interactions between the adjoining alveoli and the distending peri-airway pressure (PPA) induced in the model. The airway parenchyma model shown in Figs. 3 and 4 depict a collection of alveoli surrounding a hole in the parenchyma. The effective shear modulus (Geff) is analyzed following the analytical formulation for changes in radius for infinitely long cylindrical tubes in a homogeneous isotropic material as

| (1) |

where PPA is the peri-airway pressure and PPL is the pleural pressure. Equation 1 follows from Mead et al. (22), Lai-Fook et al. (19), and Fredberg and Kamm (5), where PPA was referred to as the peribronchial pressure. In their analyses, this pressure (the pressure from the parenchyma on the outside of the airway) was found to equal the negative of the distending stress acting just outside of the airway wall from the surrounding intact parenchyma.

The mechanical fundamentals are described in Fig. 4, with PPL < 0 indicating a positive radial stress (τrr > 0). Figure 4A demonstrates an equilibrium uniform stress state PPA = PPL, with PALV = 0, and this defines the uniform stress hole radius RH,U. In Fig. 4B, a nonuniform stress is imposed by a slight change in PPA so that PPA ≠ PPL, and the hole radius changes to RH. Equation 1 defines the shear modulus (G), with representing the fractional change in the hole radius (RH) from the uniform-stressed state RH,U when PPL is slightly modified.

Whereas Fig. 4 describes the situation for homogeneous alveolar pressures, we apply this approach for nonhomogeneous alveolar pressures (as might occur with upstream closure) and represent the fractional change in hole radius as , where RH,E is the hole radius at an equilibrium state when PPA = PPL but a fraction (fOBS) of the alveolar pressures are modified from PALV = 0. RH is the hole radius when PPA ≠ PPL. We apply Eq. 1 to evaluate an effective shear modulus Geff.

Simulation Conditions

To investigate parenchymal tethering mechanics, we conducted a series of FEM simulations in which the pressures within individual alveoli were selected randomly (using a uniform distribution) to have an internal pressure associated with 1) a normally functioning alveolus or 2) an obstructed alveolus. We assume that a normally functioning alveolus sustains PALV = 0 cmH2O; this represents atmospheric pressure and a direct connection to the mouth in a static (breath-hold) situation. In contrast, an obstructed alveolus is set to an internal pressure of either POBS = −4 cmH2O (hypoinflated) or POBS = +4 cmH2O (hyperinflated), as explained above. For any simulation, all obstructed alveoli had the same pressure, although we acknowledge that a distribution of inflation pressures could exist. The pleural pressure (PPL) was held constant at either PPL = −5 cmH2O, −10 cmH2O, or −15 cmH2O. For a given PPL, the stressed equilibrium state (RH,E) was identified, and then Geff, was measured by perturbing PPA over the range PPL − ΔP < PPA < PPL + ΔP, where ΔP = 0.2 cmH2O. The effective hole radius RH was calculated by averaging the Euclidean distance from the midpoint (mx,my) to each of the interior node points of the hole (xi,yi):

| (2) |

where the midpoint is the geometric center of the locus of points that describe the perimeter of the hole. The change of effective radius ΔR versus ΔP yields the shear modulus as determined by Eq. 1.

Computational costs.

The models we investigated are computationally large. Two issues are prominent: 1) the total memory size and 2) the total CPU time. Simulations were conducted on Tulane’s Cypress supercomputer (based upon a Dell Z9500 with Intel Xeon E5-2680 Sandy Bridge architecture). The code was constructed in C++ and utilized the MPI library, PETSC (1), and Hypre (4) for linear algebra optimization, and ParMETIS (16) for model partitioning. Using this software/hardware combination, benchmark studies demonstrated that the total computational time was inversely related to the number of processers. Thus, our computational model was highly scalable.

The memory usage as a function of the size of the model is approximately

| (3) |

Simulations were completed using two nodes, each with 20 cores.

Identification of RROI.

To investigate the parenchymal region of influence (RROI) that defines the necessary domain size to faithfully represent the solution of an infinite domain with the same fraction of obstructed alveoli, simulations were conducted with random alveolar pressure distributions with 50% obstructed alveoli. In these calculations, the outer surface (r = ROUTER/RH) is modeled as being supported by the pleural pressure [following Mead et al. (22)]. We sequentially increase ROUTER/RH to estimate the dependence of Geff on the domain size for a given fraction of obstructed (unaerated) alveoli. These were studied for , with PPL = −5 cmH2O. To identify the statistical variance, numerical experiments were conducted with n = 5 different uniformly random distributions. RROI is identified by the percentage deviation of Geff from the asymptotic value for an infinite domain, G∞. Once the region of influence was established, RROI was used for all further simulations.

Establishment of validity of the random distribution model.

To investigate the effects of localized alveolar pressure distributions for comparison with random distributions, simulations were conducted with localized obstruction distributions with the fraction of obstructed/total alveoli equal to fOBS = 0.25, 0.5, or 0.75 through the addition of quadrants of collapsed alveoli. Likewise, simulations for uniform random distributions with equivalent fOBS of were conducted. In these simulations, PPL = −5 cmH2O and POBS = −2.5 cmH2O (hypoinflated). We performed n = 5 independent trials.

Parenchymal tethering mechanics: evaluation of Geff.

After establishing ROI, we explored the functional relationship between Geff and the distribution of obstructed alveoli at specific values of PPL = −5, −10, or −15 cmH2O, with the fraction of obstructed/total alveoli, fOBS = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0. Each computational experiment was conducted with five independent trials (n = 5) to identify the statistical variance between trials.

RESULTS

Identification of Region of Influence, RROI

We estimate the region of influence (RROI) for the parenchyma surrounding an airway by Geff as a function of the domain size. From Fig. 5, it is clear that Geff converges to a finite value (G∞) with increasing RROI, which we estimate by the nonlinear regression based on the deformation of an annular disk of isotropic material:

Fig. 5.

Calculation of the effective shear modulus (Geff) as a function of the region of influence (ROI) scaled by the “hole” radius (RH).

| (4) |

For PALV = 0 and PPL = −5 cmH2O, we find G∞ = 5.836 ±0.015 cmH2O and A = 1.153 ± 0.02. From this result, we estimate the computational accuracy as a function of ROUTER/RH (see Fig. 5, inset).

In addition to accuracy, computational costs are important for considering the appropriate domain size. Table 1 presents the total memory usage and total CPU time (total wall clock time × 40 processors) for simulations as a function of the region of influence for the parenchymal domain.

Table 1.

No. of alveoli, memory usage, and computational cost associated with the domain size

| RROI/RAW | No. of Alveoli (×103) | Total Memory (GB) | Total CPU Time, h |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 6 | 3.4 | 0.3 |

| 3 | 17 | 6.6 | 34 |

| 4 | 32 | 11 | 115 |

| 5 | 51 | 17 | 190 |

| 6 | 75 | 24 | 311 |

| 7 | 103 | 32 | 444 |

| 8 | 135 | 42 | 634 |

| 9 | 172 | 53 | 797 |

CPU, central processing units; RAW, airway radius; RROI, parenchymal region of influence.

We identified ROUTER/RH = 5 as a judicious choice for the dimensionless region of influence (RROI/RH) since it provides estimates within ∼5% of G∞ at a tenable computational cost. Therefore, future full-scale models of the lung could use this RROI to accurately model parenchyma tethering effects surrounding collapsible airways.

The model depth (z-direction) for the ROI studies was set to 1.5 RH. Further convergence analysis was conducted by evaluating Geff as a function of depth. Doubling the depth resulted in only a slight increase of Geff of 3.5%, and so all further calculations were conducted with the model depth equal to 1.5 RH.

Establishment of the Validity of the Random Distribution Model

With RROI established, the effect of obstructed alveoli localization was examined with PPL = −5 cmH2O, (PALV)OPEN = 0 cmH2O and POBS = −2.5 cmH2O. Simulations were conducted to compare Geff between uniformly random distributions and localized distributions of alveoli with upstream closure. Five distinct trials with different realizations of the same uniform random distribution (n = 5) were investigated to estimate the simulation variability.

These results in Fig. 6 illustrate that there is only a very small difference in Geff between localized and random distribution models (<1%). A two-way ANOVA was conducted (P < 0.05), and Sidak multiple comparison tests were performed to show that there was no significant difference in Geff in each group.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of localization of obstructed alveoli and heterogeneous distribution. Error bars represent the standard deviation. Geff, shear modulus.

These results support our hypothesis that a random distribution of obstructed alveoli faithfully represents the large-scale parenchymal mechanics. In addition, the standard error is extremely small (<1%), which further demonstrates the robustness of the random modeling approach. Because the models with localized obstructed alveoli demonstrate equivalent Geff as the randomly distributed models, this justifies the use of the derived values of Geff for predictions of mechanical interactions that can occur in ARDS.

Evaluation of Geff

With our two fundamental questions satisfied, we sought to explore the overall mechanical properties of systems with a subset of obstructed alveoli with PPL = −5, −10, or −15 cmH2O. We explored this behavior as a function of the transpulmonary pressure (PTP), where PTP = (PALV)open − PPL, with (PALV)open = 0, with obstructed alveoli in either the hyperinflated (POBS = +4 cmH2O) or hypoinflated state (POBS = −4 cmH2O). The fraction of obstructed alveoli was varied over 0 ≤ fOBS ≤ 1 in increments of 0.2.

Data from these simulations are shown in Fig. 7A and indicate that hyperinflated obstructed alveoli cause an increase in Geff, whereas hypoinflation causes a reduction of Geff. The degree of change in Geff is monotonically related to fOBS. We note that increasing the ratio of hypoinflated-obstructed alveoli causes local distension of nearby open alveoli, which causes those alveoli to slightly stiffen. Nevertheless, the increase in hypoinflated alveoli causes the size of the entire domain to reduce since the domain is not a fixed size (the external boundary condition is defined by PPL). This results in a net softening of the parenchyma, leading to a mesoscale reduction of Geff. The opposite is true for hyperinflated alveoli, leading to a mesoscale increase of Geff.

Fig. 7.

A: shear modulus (Geff) as a function of transpulmonary pressure (PTP) with aerated alveoli (PALV)open = 0 and hyperinflated obstructed alveoli (POBS) = +4 cmH2O (shaded blue) or hypoinflated obstructed alveoli POBS = −4 cmH2O (shaded green) for pleural pressure (PPL) = −5 cmH2O (△), PPL = −10 cmH2O (▽), and PPL = −15 cmH2O (○). Fraction of obstructed alveoli varies over 0 ≤ fOBS ≤ 1. B: shear modulus (G_eff) as a function of the weighted average transpulmonary pressure.

Geff as a Function of the Mean Alveolar Pressure

We seek a representation that will collapse the data from Fig. 7A to a single relationship to facilitate incorporation into a reduced-dimension model of the lung. To explore this behavior, we investigated Geff as a function of the weighted average transpulmonary pressure ()

| (5) |

where PPL is the pleural pressure and is the average of the all the alveolar pressures within the parenchyma:

| (6) |

Figure 7B re-expresses the data from Fig. 7A, demonstrating that effectively collapses the data to a master curve. These data were fit to an exponential function:

| (7) |

where A = 4.75 ± 0.12 cmH2O and B = 5.17 × 10−4 ± 4.9 × 10−6 cmH2O−3, which provides a coefficient of determination of r2 = 0.99.

DISCUSSION

The analysis above demonstrates that a single master curve exists that can be used to estimate Geff as a function of the fraction of alveoli and the pressures within obstructed and unobstructed alveoli in proximity to the airway. This result can be used to estimate the parenchymal tethering mechanics of embedded collapsed airways without resorting to a complete FEM model that would otherwise require an extraordinary computational expense (see Table 1). The mesoscale empirical behavior from these reduced-dimension results allows for the incorporation of parenchymal mechanics into a model of a heterogeneous distribution of obstructed alveoli within the parenchyma using feasible computational resources.

Figure 7B compares our predictions of Geff to estimates from experiments by Lai-Fook et al. (19), which were conducted to analyze the mechanical properties of isolated dog lobes. These simulations demonstrate that agreement is best over the range 6 < < 12 cmH2O. At smaller values of , our simulations overestimate Geff, although both the simulations and experiments indicate a similar reduction in slope. We speculate that our overestimate of Geff is due to either a surfeit of fibers over that which exists physiologically or alveolar structural collapse that was not simulated. Our model includes a realistic reduction of surface tension with alveolar volume, and so we do not attribute the deviation to be due to surfactant effects. For < 12 cmH2O, the nonlinear increase in Geff results from a highly nonlinear stiffness characteristic of collagen, which becomes more significant as the prestress increases with . This behavior is similar to that described by Denny and Schroter (3). In this range, the overall system may be stiffer than experimentally observed because of cross-linked fibers that exist at the faces of our alveolar elements. As described in the excellent review article by Stamenović (28), this may explain some of the nonlinear increase in Geff. Furthermore, it has also been suggested by Fredberg and Kamm (5), following the work of Budiansky and Kimmel (2), that differences in microscale stiffness from the macroscale could deviate in a nonaffine manner as a result of structural connectedness and prestress within the structural matrix. We note that our models were developed with fiber densities, following the studies of Mercer and Crapo (23). Although they were not tuned, it would be possible to change these values to better fit the experiments by Lai-Fook et al. (19). Furthermore, fiber properties may change in disease, and therefore, it would be valuable to predict Geff equations of state for a range of diseases from fibrosis to emphysema.

Application of Parenchymal Tethering Analysis in a Simple Airway Model

To demonstrate the implementation of the reduced-dimension mechanics of the parenchyma, a simplified model was constructed with a single airway surrounded by parenchyma using the “pig-in-a-blanket” model illustrated in Fig. 8, with an airway laminated inside the parenchymal hole that was used to calculate Geff.

Fig. 8.

Simple airway model of conducting airway surrounded by parenchyma with heterogeneously distributed obstructed alveoli. PAW, airway pressure; RAW, airway radius;

In this application, the airway transmural pressure is influenced by the peri-airway pressure induced by the parenchymal tethering mechanics and the liquid lining that reduces the internal pressure by the Law of Laplace. This relationship is provided by

| (8) |

where PTM is the transmural pressure, PAW is the airway pressure, Geff is the effective shear modulus, , PPL is the pleural pressure, γ is the surface tension, and h is the liquid lining. The change in the airway radius is governed by a tube law of the form proposed by Lambert et al. (21) and schematically illustrated in Fig. 9. Additionally, this model assumes that the airway wall has no thickness, so airway radius (RAW) = RH.

Fig. 9.

Tube law at the trachea (z = o) and an airway at the 16th generation (z = 16).

A series of simulations were conducted on this single-airway model following the protocol implemented by Ryans et al. (27). In this analysis, we investigate only the interrelationship of the parenchymal tethering and the transmural pressure of the airway to observe the effects on airway caliber. We neglect the pressure difference between the airway and alveoli that could drive flow, and thus this is a nonequilibrium analysis.

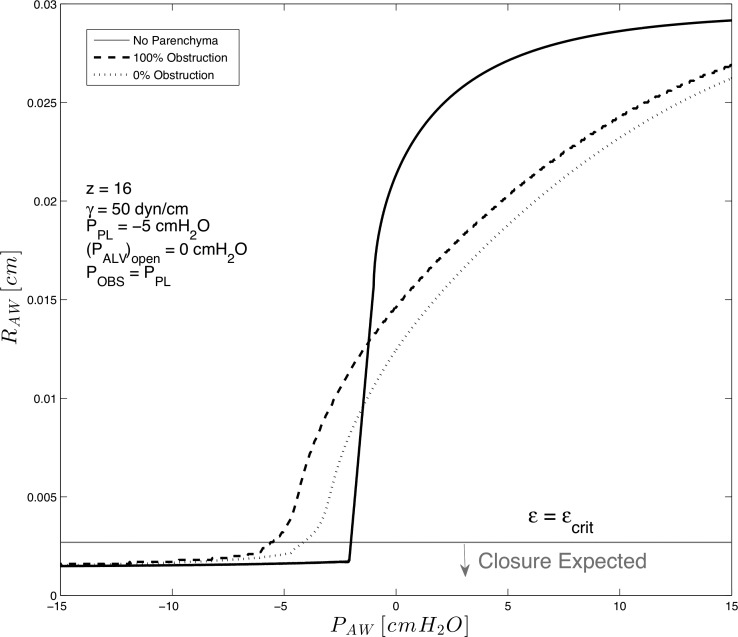

We consider the effect of parenchymal tethering of a highly compliant 16th generation airway incorporating parenchyma with (fOBS = 0, 1) of obstructed alveoli in a hypo-inflated state, POBS = −2.5 cmH2O, with PPL = −5 cmH2O. As a simple model of ARDS, we investigate a high surface tension case with , and a “wet lung” with (Vliq/VAW)min =0.05, where Vliq and VAW are the liquid lining volume and airway volume at the maximally inflated state.

RAW was investigated as PAW was reduced from the maximally inflated pressure correlating to RAW = RAW,max. In this analysis, we predict the stability from the dimensionless liquid-lining thickness, ε = h/RAW. As the airway radius decreases with reduced PAW, h increases due to conservation of mass, and therefore, ε increases. We assume that the airway becomes unstable to fluid-structure instabilities when εcrit = 0.12, leading to the formation of a liquid-bridge obstruction that would cause the acinus for this airway to enter an obstructed state (9–11, 14, 15). In multiple airway systems, this would in turn influence Geff for the parenchyma surrounding airways in which the RROI intersected that acinus, possibly leading to large-scale effects by reducing the tethering behavior of those airways, and so on.

Figure 10 demonstrates the airway radius under conditions of 1) the limiting case of a completely untethered airway, 2) an airway surrounded by parenchyma with completely open alveoli (0% obstruction), and 3) an airway surrounded by hypoinflated obstructed alveoli (100% upstream obstruction, POBS =−2.5 cmH2O).

Fig. 10.

Simulation of a collapsible 16th generation airway without parenchymal support (solid line), with parenchymal support (dashed line), and with parenchymal support from hypoinflated obstructed alveoli (POBS = −2.5 cmH2O, fOBS = 1, dotted line). PPL = −5 cmH2O, γ = 50 mN/m.

These results show that an airway without surrounding parenchyma collapses at much greater PAW than an airway surrounded by either unobstructed or obstructed alveoli. This limiting case demonstrates effects related to the complete lack of parenchyma and shows the intuitive result that an increase in PAW increases stability. Following intuition, parenchyma has a stabilizing effect, with airway patency retained for PAW > −5 cmH2O when all alveoli are unobstructed; however, stability only exists for PAW > −3.5 cmH2O if all alveoli are hypoinflated, since Geff is greater when alveoli sustain an inflated state. Interestingly, when PAW > 0 cmH2O, we show that parenchyma restrains the expansion of the airway, implying that the airway is pushing against the surrounding alveoli when the nonequilibrium airway-to-alveolar pressure distribution exists.

These results demonstrate the importance of increasing PAW when tethering is reduced. Positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation (PEEP) accomplishes this by retaining PAW > 0 cmH2O and increases the tethering effects due to an increase in Geff by increasing alveolar volume. Our model predicts that the nonlinear increase in Geff that occurs with induces an added protective effect that could reduce the incidence of airway closure.

Limitations

As with all models, limitations exist owing to model assumptions. For example, we assumed that alveolar membranes that make up the parenchymal tissue act isotropically. Although this is an accurate representation for uniformly inflated alveoli (30), this property is violated when collapse occurs; nevertheless, we evaluate Geff by following a continuum approach assuming perturbations from the base state. Furthermore, the lung exhibits a viscoelastic behavior (24) that is not modeled. We have also explored only a limited parameter space; when comparing randomly distributed obstructions and comparing with local distributions, we could have investigated configurations other than quadrants. Additionally, a larger range of PPL and POBS could have been studied to establish the robustness of the generalization proposed herein. As described above, we ignore fluid flow and dynamic processes such as surfactant physicochemical hydrodynamics that induce hysteresis in the pressure-volume relationship that can be significant in atelectrauma and will be investigated in follow-up models. We also ignore variation in lung stiffnesses due to differences in airway wall properties; this would be incorporated through a change in the tube law demonstrated in Fig. 9. We also ignore the septal thickness associated with parenchymal tethering, which is generationally dependent. The mechanical effects of wall buckling are ignored aside from the change in area associated with the tube law. To include buckling at the microscale is inconsistent with our reduced-dimension modeling approach.

This study assumed only that obstructed alveoli were air-filled with an upstream obstruction and that this obstruction reduced the volume of the alveolus (hence reducing the volume of the entire model). Alternatively, these structures could be fluid filled, which would change their elastic behavior and tethering mechanics (likely increasing Geff). We were also constrained to investigate alveoli that had not completely collapsed when, in fact, alveoli may collapse from low internal pressures caused by absorption atelectasis. Finally, we also note that we have investigated an idealized configuration of a compliant airway surrounded by alveoli; we have not investigated alveolar ducts, and we also assume that neighboring airways are not within the region of influence.

Nevertheless, this study has demonstrated the development of the multiscale computational model of parenchyma that can be used to evaluate the mesoscale parenchymal tethering properties on highly compliant airways. Analyses of the computational data demonstrate that a single empirical relationship exists when Geff is represented as a function of the volume-average transpulmonary pressure of the surrounding alveoli. This empirical relationship can be used to computationally model multiscale phenomena under conditions of obstructive lung disease. These simulations could provide information related to volutrauma or atelectrauma during mechanical ventilation and thus could help to forecast the efficacy of novel protective ventilation scenarios.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Science Foundation Grant NSF CBET-1706801, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant 1R01-HL-142702-01, and Research Traineeship Grant DMS-1043626. Computational resources were supported in part using high-performance computing resources and services provided by Information Technology at Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, and the Louisiana Optical Network Infrastructure.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M.R., H.F., and D.P.G. conceived and designed research; J.M.R. and H.F. performed experiments; J.M.R., H.F., and D.P.G. analyzed data; J.M.R., H.F., and D.P.G. interpreted results of experiments; J.M.R., H.F., and D.P.G. prepared figures; J.M.R. and D.P.G. drafted manuscript; J.M.R., H.F., and D.P.G. edited and revised manuscript; J.M.R., H.F., and D.P.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balay S, Abhyankar S, Adams M, Brune P, Buschelman K, Dalcin L, Gropp W, Smith B, Karpeyev D, Kaushik D. Petsc Users Manual Revision 3.7. Argonne, IL: Argonne National Laboratory, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budiansky B, Kimmel E. Elastic moduli of lungs. J Appl Mech 54: 351–358, 1987. doi: 10.1115/1.3173019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denny E, Schroter RC. A model of non-uniform lung parenchyma distortion. J Biomech 39: 652–663, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falgout RD, Yang UM. Hypre: a library of high performance preconditioners. In: Computational Science – ICCS 2002 Part III, edited by Sloot PMA, Tan CJK, Dongarra JJ, and Hoekstra AG. International Conference on Computational Science Springer-Verlag, 2002, p. 632–641. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredberg JJ, Kamm RD. Stress transmission in the lung: pathways from organ to molecule. Annu Rev Physiol 68: 507–541, 2006. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.072304.114110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujioka H, Halpern D, Gaver DP III. A model of surfactant-induced surface tension effects on the parenchymal tethering of pulmonary airways. J Biomech 46: 319–328, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujioka H, Halpern D, Ryans J, Gaver DP III. Reduced-dimension model of liquid plug propagation in tubes. Phys Rev Fluids 1: 053201, 2016. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevFluids.1.053201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaver DP III, Samsel RW, Solway J. Effects of surface tension and viscosity on airway reopening. J Appl Physiol (1985) 69: 74–85, 1990. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grotberg JB, Jensen OE. Biofluid mechanics in flexible tubes. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 36: 121–147, 2004. doi: 10.1146/annurev.fluid.36.050802.121918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halpern D, Grotberg J. Fluid-elastic instabilities of liquid-lined flexible tubes. J Fluid Mech 244: 615–632, 1992. doi: 10.1017/S0022112092003227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond P. Nonlinear adjustment of a thin annular film of viscous fluid surrounding a thread of another within a circular cylindrical pipe. J Fluid Mech 137: 363–384, 1983. doi: 10.1017/S0022112083002451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higuita-Castro N, Mihai C, Hansford DJ, Ghadiali SN. Influence of airway wall compliance on epithelial cell injury and adhesion during interfacial flows. J Appl Physiol (1985) 117: 1231–1242, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00752.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain SV, Kollisch-Singule M, Satalin J, Searles Q, Dombert L, Abdel-Razek O, Yepuri N, Leonard A, Gruessner A, Andrews P, Fazal F, Meng Q, Wang G, Gatto LA, Habashi NM, Nieman GF. The role of high airway pressure and dynamic strain on ventilator-induced lung injury in a heterogeneous acute lung injury model. Intensive Care Med Exp 5: 25, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s40635-017-0138-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson M, Kamm RD, Ho LW, Shapiro A, Pedley T. The nonlinear growth of surface-tension-driven instabilities of a thin annular film. J Fluid Mech 233: 141–156, 1991. doi: 10.1017/S0022112091000423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamm RD, Schroter RC. Is airway closure caused by a liquid film instability? Respir Physiol 75: 141–156, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(89)90059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karypis G, Kumar V. A parallel algorithm for multilevel graph partitioning and sparse matrix ordering. J Parallel Dist Comput 48: 71–95, 1998. doi: 10.1006/jpdc.1997.1403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan MA, Ellis R, Inman MD, Bates JH, Sanderson MJ, Janssen LJ. Influence of airway wall stiffness and parenchymal tethering on the dynamics of bronchoconstriction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299: L98–L108, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00011.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krueger MA, Gaver DP III. A theoretical model of pulmonary surfactant multilayer collapse under oscillating area conditions. J Colloid Interface Sci 229: 353–364, 2000. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2000.7029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai-Fook SJ, Hyatt RE, Rodarte JR. Effect of parenchymal shear modulus and lung volume on bronchial pressure-diameter behavior. J Appl Physiol 44: 859–868, 1978. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.44.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai-Fook SJ, Hyatt RE, Rodarte JR, Wilson TA. Behavior of artificially produced holes in lung parenchyma. J Appl Physiol 43: 648–655, 1977. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1977.43.4.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert RK, Wilson TA, Hyatt RE, Rodarte JR. A computational model for expiratory flow. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 52: 44–56, 1982. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mead J, Takishima T, Leith D. Stress distribution in lungs: a model of pulmonary elasticity. J Appl Physiol 28: 596–608, 1970. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1970.28.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mercer RR, Crapo JD. Spatial distribution of collagen and elastin fibers in the lungs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 69: 756–765, 1990. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.2.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navajas D, Maksym GN, Bates JH. Dynamic viscoelastic nonlinearity of lung parenchymal tissue. J Appl Physiol (1985) 79: 348–356, 1995. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.1.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perun ML, Gaver DP III. Interaction between airway lining fluid forces and parenchymal tethering during pulmonary airway reopening. J Appl Physiol (1985) 79: 1717–1728, 1995. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.5.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryans J, Fujioka H, Halpern D, Gaver DP. Reduced-dimension modeling approach for simulating recruitment/de-recruitment dynamics in the lung. Ann Biomed Eng 44: 3619–3631, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1672-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stamenović D. Micromechanical foundations of pulmonary elasticity. Physiol Rev 70: 1117–1134, 1990. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venegas JG, Winkler T, Musch G, Vidal Melo MF, Layfield D, Tgavalekos N, Fischman AJ, Callahan RJ, Bellani G, Harris RS. Self-organized patchiness in asthma as a prelude to catastrophic shifts. Nature 434: 777–782, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nature03490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson TA. A continuum analysis of a two-dimensional mechanical model of the lung parenchyma. J Appl Physiol 33: 472–478, 1972. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.33.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yap DY, Liebkemann WD, Solway J, Gaver DP 3rd. Influences of parenchymal tethering on the reopening of closed pulmonary airways. J Appl Physiol (1985) 76: 2095–2105, 1994. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.5.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]