Abstract

Objective:

To examine whether race predicted or moderated response to treatments for binge-eating disorder (BED).

Method:

Participants were 592 adults (n=113 Black; n=479 White) with DSM-IV-defined BED who participated in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) at one medical center. Data were aggregated from RCTs for BED testing cognitive-behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, multi-modal treatment, and/or control conditions. Participants had weight and height measured and were assessed using established interviews and self-report measures at baseline, throughout treatment, and post-treatment.

Results:

Race did not significantly moderate treatment outcomes. Mixed models revealed a main effect of race: Black participants had fewer binge-eating episodes and lower depression than White participants across time points. Race also had a main effect in generalized estimating equations with a significantly greater proportion of Black participants achieving binge-eating remission than White participants. Race did not predict percent weight loss, but a significantly lower proportion of Black participants attained 5% weight loss than White participants. Race did not significantly predict global eating-disorder severity.

Conclusion:

Despite disparities in treatment-seeking reported in epidemiological and RCT studies, Black individuals appear to have comparable or better treatment outcomes in BED treatment research compared with White individuals, except they were less likely to attain 5% weight loss at post-treatment. This suggests that disseminating evidence-based treatments for BED among diverse populations holds promise and treatments may not require further adaptation prior to dissemination. Implementation research is needed to test treatment effectiveness across diverse providers, settings, and patient groups to improve understanding of potential predictors and moderators.

Keywords: binge-eating disorder, eating disorders, race, treatment, weight, moderators, predictors, randomized controlled trials, obesity

Introduction

Binge-eating disorder (BED), the most prevalent formal eating disorder among adults (Udo & Grilo, 2018), is characterized by recurrent binge-eating episodes (i.e., eating unusually large amounts of food while experiencing a subjective sense of loss of control over eating) without the weight-compensatory behaviors that define bulimia nervosa (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Individuals across racial/ethnic groups experience clinically significant eating-disorder psychopathology and this is especially the case for BED (Marques et al., 2011; Udo & Grilo, 2018).

Although BED is prevalent among Black individuals (Marques et al., 2011; Udo & Grilo, 2018), little is known about racial similarities or differences in BED. Prior research examining baseline characteristics of treatment-seeking individuals with BED found that Black participants begin treatment at higher weights than White participants (Franko et al., 2012; Lydecker & Grilo, 2016) and report similar or higher frequencies of binge-eating episodes (Franko et al., 2012; Lydecker & Grilo, 2016), but otherwise have similar eating-disorder psychopathology (Lydecker & Grilo, 2016) and impairment (Marques et al., 2011). Yet, despite the observed clinical need, Black individuals are less likely than White individuals to seek mental health treatment for BED (Marques et al., 2011) and are underrepresented in clinical trials (Franko et al., 2012).

Although there is general empirical support for psychological (Grilo, 2017b), pharmacological (Reas & Grilo, 2015), and combination or “multi-modal” (Grilo, Reas, & Mitchell, 2016) treatments for BED, many patients do not benefit sufficiently from treatments or fail to cease binge eating or lose weight. Understanding characteristics of patients who are likely to benefit from specific treatments is critical to inform clinical decision-making and requires tests of predictors and moderators of treatment outcomes (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002; Wilson, Grilo, & Vitousek, 2007). Most treatment trials for BED have not had sufficient power to test race as a predictor or moderator of treatment outcomes and one approach to overcome this deficit has made use of aggregated data (Thompson-Brenner et al., 2013). Thompson-Brenner et al. (2013) pooled data from 11 clinical trials that tested psychosocial treatments for adults with BED. Analyses with Black (n=79), Hispanic (n=48) and White (n=946) participants revealed that race/ethnicity did not significantly moderate treatment response. Race/ethnicity did, however, significantly predict some treatment outcomes: Black participants had significantly lower global eating-disorder psychopathology than White participants yet were also significantly more likely to drop out of treatment than White participants. Findings from these analyses of pooled clinical trial data make an important contribution to the field and require replication and extension for several reasons, including: (1) pooled data came from different research sites that used similar but methodologically different assessment tools for eating-disorder psychopathology; (2) research sites contributed data with different racial representation, which may reflect varying degrees of differences in recruitment strategies, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and screening and assessment procedures; (3) only participants who received active psychological treatments were included (i.e., control conditions were excluded from analyses); and (4) non-psychological interventions, such as pharmacotherapy and multi-modal interventions, were not considered, thus substantially limiting generalizability. Thus, additional research is needed to characterize potential racial differences in treatment outcomes among adults with BED.

The current study examined race as a potential moderator and predictor of key BED treatment outcomes: binge-eating episodes both continuously (frequency) and categorically (remission), weight both continuously (percent loss) and categorically (attainment of 5% loss), global eating-disorder severity, and depression scores. Weight loss was defined categorically at 5% because this threshold is associated with clinical/medical benefits (Goldstein, 1992; Jensen et al., 2014). Data were aggregated from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for BED performed at one research location using similar recruitment and assessment protocols.

RCTs included in the current analyses tested cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), behavioral weight loss (BWL), multi-modal treatments, and/or control conditions. The RCTs all assessed participants for eligibility using a consistent, interview-based evaluation of eating-disorder psychopathology and binge eating, used similar assessment batteries, and measured height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI) and percent weight loss at similar repeated time points.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N=592) were patients in psychological and pharmacological RCTs for BED (Grilo, 2017a; Grilo & Masheb, 2005; Grilo, Masheb, & Salant, 2005; Grilo et al., 2014; Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2005; Grilo, Masheb, Wilson, Gueorguieva, & White, 2011; Grilo, White, Gueorguieva, Barnes, & Masheb, 2013). Three of these RCTs (Grilo & Masheb, 2005; Grilo, Masheb, & Salant, 2005; Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2005) provided cognitive-behavioral therapy data for the analyses previously conducted by Thompson-Brenner et al (2013). Treatment studies occurred at an urban, medical-school based program in the northeastern United States. Participants were 18–65 years old and met full DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2004) criteria for BED1. Participants were excluded if they were receiving concurrent treatment (psychosocial or pharmacological) for eating/weight concerns, had medical conditions that influenced eating/weight (e.g., uncontrolled hypothyroidism), were taking medications that could influence eating/weight, had a severe mental illness that could interfere with clinical assessment (e.g., psychosis), or were pregnant.

Overall, 592 participants (Black, 19.1%, n=113, and White, 80.9%, n=479) were included in the current analyses2. Participants had a mean age of 46.43 (SD=9.59) years and mean BMI of 37.56 (SD=6.22) kg/m2. Participants were men (26.0%, n=154) and women (74.0%, n=438). Participants had varying levels of education: high school or less (17.6%, n=104), some college (34.0%, n=201), or a college degree or more (48.1%, n=285); two participants did not report their educational attainment.

Overall, 82.3% of Black participants were women (n=93) and 72.0% of White participants were women (n=345), which differed significantly (χ2(1, N=592)=5.02, p=.025, φ=.092). Among Black participants, 28.3% (n=32) had a high school education, 41.6% (n=47) had some college education, and 30.1% (n=34) had a college degree. Among White participants, 15.1% (n=72) had a high school education, 32.3% (n=154) had some college education, and 52.6% (n=251) had a college degree; education differed significantly between Black and White participants (χ2(2, N=590)=20.99, p<.001, φ=.189). The average age of Black participants in the current study was 45.40 (SD=10.14) years; the average age of White participants was 46.67 (SD=9.46) years, which did not differ significantly (t590=−1.27, p=.205). The average BMI of Black participants (M=39.68 kg/m2, SD=6.29) was significantly higher than for White participants (M=37.08 kg/m2, SD=6.08) (t589=4.08, p<.001).

This study received approval from our university’s institutional review board and all participants provided written informed consent prior to study assessments.

Treatments

Treatments were CBT, BWL, multi-modal treatments (i.e., CBT or BWL plus pharmacotherapy), and control conditions (i.e., double-blind trial with placebo or unguided self-help or inert attention-for-control condition). These treatments reflected the emerging literature on psychological (Grilo, 2017b) and pharmacological (McElroy, 2017) treatments for BED, and more detailed descriptions of the individual RCTs have been published previously (Grilo, 2017a; Grilo, Masheb, & Salant, 2005; Grilo et al., 2014; Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2005; Grilo et al., 2011; Grilo et al., 2013).

Treatments lasted between 3 and 6 months, which generally parallels the broader literature on RCTs for BED (Grilo, 2017b; McElroy, 2017; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017; Reas & Grilo, 2015). To standardize the amount of data contributed across protocols, assessment time points included in the current analyses occurred at baseline, one month into treatment, two months into treatment, and at post-treatment. Assessments were performed independently by doctoral-level research evaluators who were blinded to both the medication and behavioral treatment status.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

CBT followed the manualized treatments developed initially by Fairburn and colleagues and since expanded and used in numerous RCTs testing CBT (e.g., Wilfley et al., 2002). Manualized CBT was administered by trained and monitored doctoral-level research-clinicians. CBT focuses on establishing a therapeutic relationship, providing psychoeducation about binge eating and associated problems, as well as teaching specific behavioral strategies that help patients identify problematic eating patterns and make their eating more regular, such as self-monitoring and goal-setting. CBT also focuses on identifying and modifying maladaptive cognitive processes specific to eating disorders and their maintenance through cognitive restructuring. Finally, CBT teaches methods to foster maintenance of change and prevent relapse. CBT is considered the best evidence-based psychological treatment for BED and has been highlighted as the treatment of choice for BED by some guidelines (Grilo, 2017b; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017; Wilson, Wilfley, Agras, & Bryson, 2010) and is widely used in BED treatment studies.

Controlled research has also supported the effectiveness of CBT delivered via guided self-help (e.g., Wilson et al., 2010; See Wilson & Zandberg, 2012 for review). Guided self-help CBT covers the same content as full CBT. Additional instruction for clinicians in a clinician manual facilitates the implementation of the guided self-help CBT protocol by including specific references to patient materials for key sections and exercises. In the guided self-help approach, research-clinicians primarily focus on: (a) maintaining and enhancing motivation, (b) correcting any misunderstanding of information, (c) problem-solving difficulties using relevant skills and exercises from patient materials, and (d) reinforcing the importance of self-monitoring and record keeping.

Behavioral Weight Loss (BWL).

BWL followed the manualized treatment developed initially as the LEARN Program for Weight Management (Brownell, 2000) and since expanded and used in numerous RCTs testing BWL for BED (Devlin, Goldfein, Petkova, Liu, & Walsh, 2007; Wilson et al., 2010) and obesity (Wadden et al., 2011). BWL was administered by trained and monitored doctoral-level research-clinicians and focuses on making gradual behavioral lifestyle changes to nutrition and exercise through moderate caloric restriction and increases in physical activity. Nutritional advice was consistent with federal recommendations. Specific strategies included collaborative goal setting, self-monitoring, and use of social support.

Multi-Modal Treatment (Multi).

Multi-modal treatment included BWL or CBT treatment combined with pharmacological treatment. In addition to behavioral treatments, participants receiving medications were managed by study-physicians who were trained in the medication-delivery study protocols and monitored with regard to ongoing medication issues including compliance and side effects. Medications (across studies) were sibutramine, orlistat, or fluoxetine, which have varied levels of support across studies as either mono- or combination-therapy (Grilo et al., 2016; McElroy, 2017; Reas & Grilo, 2015)3.

Control Conditions.

In studies with active medications, the control treatment was placebo medication. Placebos were matched and visually identical to the active medication. In studies with behavioral interventions, the control condition was either a) unguided self-help treatment or b) daily self-monitoring forms only. In unguided self-help treatments, patients were given a copy of a CBT book (Fairburn, 1995) and were told to read the book and follow the self-help recommendations included in the text. Patients were also encouraged to follow recommendations regarding record keeping and goal setting.

Measures

Research-clinicians administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997) to determine the DSM-IV-based BED diagnosis and the semi-structured, investigator-based Eating Disorder Examination interview (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) to confirm the BED diagnosis for study eligibility. The EDE interview measures eating-disorder psychopathology over the prior three months and generates diagnoses corresponding to the DSM across editions. All research-clinicians had doctoral-level training, had additional training in these specific assessment instruments, and were supervised and monitored to maintain reliability and protect against drift. Each of the individual RCTs reported good inter-rater reliability data for the EDE interview.

Percent Weight Loss.

Research-clinicians measured participants’ weight to calculate percent weight loss (the difference between a later weight and the baseline weight, divided by the baseline weight; negative values indicate weight loss).

Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q).

The EDE-Q is the self-report version of the EDE (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994). The self-report and interview versions have been found to converge adequately among patients with BED (Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2001a, 2001b), including Black patients with BED (Lydecker, White, & Grilo, 2016). The EDE-Q assesses binge-eating episodes in the past 28 days and generates a global severity score that reflects eating concerns, weight concerns, shape concerns, and dietary restraint. The EDE-Q has excellent test-retest reliability among patients with BED (Reas, Grilo, & Masheb, 2006).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

The BDI is a well-established measure of depression (Beck & Steer, 1987) that captures a broad range of negative affect. The BDI has excellent psychometric properties (Beck, Steer, & Carbin, 1988). Each of the individual RCTs reported excellent internal consistency values for the BDI.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses, which included all randomized participants (i.e., intent-to-treat) with at least one post-baseline measure, compared Black and White participants on treatment outcomes: binge-eating episodes both continuously (frequency) and categorically (remission), weight both continuously (percent loss) and categorically (attainment of 5% loss), EDE-Q global eating-disorder psychopathology, and BDI depression scores. Because the aggregated treatments ranged from 3 to 6 months, analyses have used all available data from baseline, month 1, month 2 and post-treatment. Descriptive statistics were evaluated prior to statistical analyses and distributions of all outcome variables were examined. Log-transformation was applied to binge-eating episode frequency and square-root transformation was applied to depression scores prior to analyses to meet assumptions of normality. “Remission” from binge eating was defined as zero binge-eating episodes during the previous 28 days. For binge-eating remission and 5% weight loss, analyses were performed with failure imputed for missing data and on all available data. Significance level of .05 was used to evaluate all tests.

Continuous outcome variables for Black and White participants were compared using mixed models (SAS PROC MIXED), making use of all available data. In the mixed models, fixed effects were race (Black and White), treatment group (CBT, BWL, multi-modal, and control), time (baseline, month 1, month 2, and post) and all possible interactions. Baseline was not included as a time point in analyses of percent weight loss (as change is calculated from baseline values). For each model, different variance-covariance structures (unstructured (UN), compound symmetry (CS), compound symmetry heterogeneous (CSH) with and without a random effect for protocol) were evaluated and the best-fitting structure was selected based on Schwartz Bayesian criterion (BIC). Least square means were estimated from all models and compared as necessary to explain significant effects in the models.

The categorical binge-eating remission variable was analyzed using a Generalized Estimating Equations model with binomial response distribution and logit link. Race (Black and White), treatment condition (CBT, BWL, multi-modal, and control), and time (month 1, month 2, and post) were included as variables in the models that used all available data and those that used imputed data (with failure, i.e., non-remission, imputed for missing data). Baseline values were not included in this analysis (as binge-eating episodes were required for eligibility). The categorical 5% weight loss variable was analyzed using Fisher’s exact test at the post time point. Proportions of participants achieving 5% weight loss were compared by race and by treatment group using both all available data and imputed data (described above).

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Race

Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of Black and White participants across treatment evaluation time points. Completed assessments and available data did not significantly differ between Black and White participants at month 1 (Black: 77.9%, n=88; White: 78.9%, n=378), month 2 (Black: 89.4%, n=101; White: 94.2%, n=451) and post (Black: 85.8%, n=97; White: 90.8%, n=435) (all ps>.05).

Table 1.

Clinical variables by race and time point.

| Baseline | Month 1 | Month 2 | Post | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | White | Black | White | Black | White | Black | White | |

| Binge-eating frequency, M (SD) | 11.45* (7.96) | 14.80 (9.58) | 5.85* (8.25) | 7.42 (8.30) | 3.75* (5.45) | 4.82 (6.90) | 3.09* (5.90) | 3.92 (6.48) |

| Binge-eating remission, n (%) | n/a | n/a | 24* (29.3%) | 49 (14.1%) | 35* (38.0%) | 118 (29.7%) | 47 (49.5%) | 181 (43.4%) |

| Percent weight loss, M (SD) | n/a | n/a | 0.001%* (3.67%) | −0.964% (2.79%) | −0.713% (4.07%) | −1.967% (3.73%) | −2.131% (5.91%) | −3.133% (5.92%) |

| 5% weight loss, n (%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 16* (17.2%) | 125 (31.6%) |

| Eating-disorder psychopathology, M (SD) | 3.45 (0.98) | 3.51 (0.97) | 2.77 (1.10) | 2.93 (0.93) | 2.57 (1.10) | 2.77 (0.96) | 2.38 (1.16) | 2.59 (1.06) |

| Depression scores, M (SD) | 14.55* (9.72) | 16.40 (8.68) | 10.48* (8.25) | 11.62 (8.29) | 9.30* (7.74) | 11.11 (8.30) | 8.49* (7.48) | 9.78 (8.14) |

Note. N=592. Black (n=113), White (n=479). Remission and 5% weight loss values are not imputed.

Significant difference between Black and White participants, p<.05; omitted asterisks indicate non-significant difference between Black and White participants.

All conditions included both Black and White individuals: CBT (Black: 12.1%, n=19; White: 87.9%, n=138), BWL (Black: 17.0%, n=18; White: 83.0%, n=88), multi-modal (Black: 16.7%, n=35; White: 83.3%, n=175), and control (Black: 34.5%, n=41; White: 65.5%, n=78). The proportion of Black participants in each treatment condition did not differ significantly from the overall proportion of Black participants in the current analyses (all ps>.05).

Retention at post was excellent across treatment conditions: 89.2% for CBT (n=140), 84.0% for BWL (n= 89), 91.0% for multi-modal (n=191), and 94.1% for control conditions (n=112). The proportion of available data for each treatment condition did not differ significantly from the overall proportion in the current analyses (all ps>.05).

Binge-eating Frequency and Remission

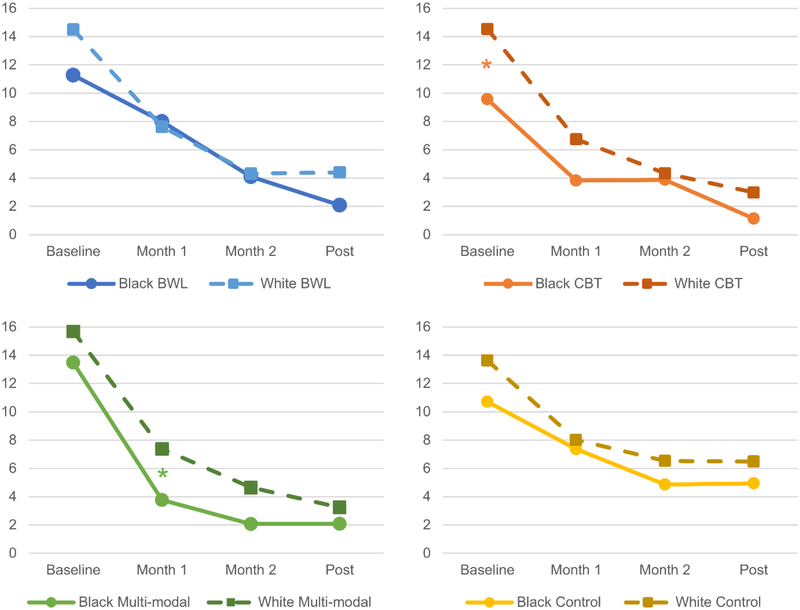

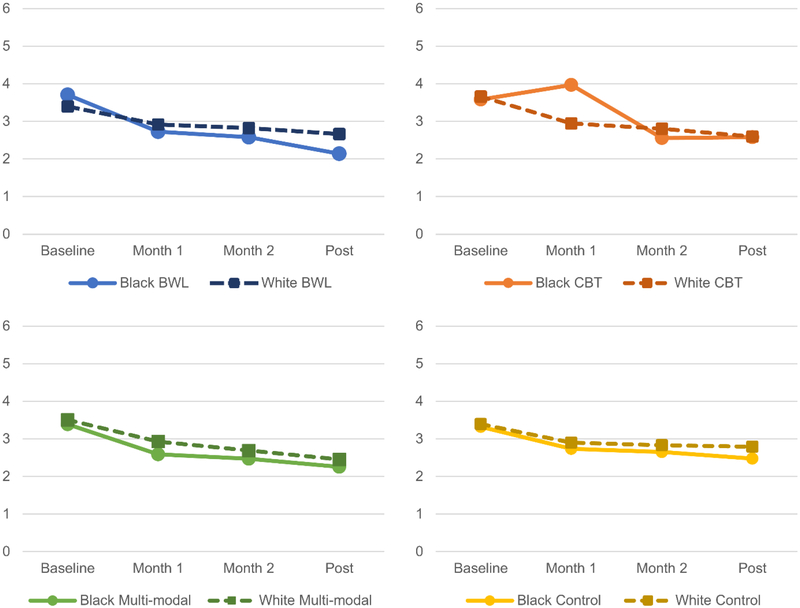

Figure 1 depicts mean binge-eating frequency by race, time, and treatment. The race by treatment by time interaction was not significant, which indicates that race did not significantly moderate treatment effects. There was a significant main effect of race (F1,616=13.02, p<.001): Black participants had fewer binge-eating episodes than White participants. There was a significant treatment by time interaction (F9,609=3.31, p<.001). There were also significant main effects of treatment (F3,125=3.15, p=.027), and time (F3,542=160.09, p<.0001). Treatment differences were evident at month 2 (p=.005) and at post-treatment (p<.001). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that multi-modal treatment (p=.010) and CBT (p=.013) were associated with significantly greater reductions in binge-eating episodes compared with control conditions. Overall, there were significant reductions in binge-eating frequency over time.

Figure 1.

Binge-eating Frequency by Race, Treatment, and Time

* Significant difference between Black and White participants, p<.05; omitted asterisks indicate non-significant difference between Black and White participants.

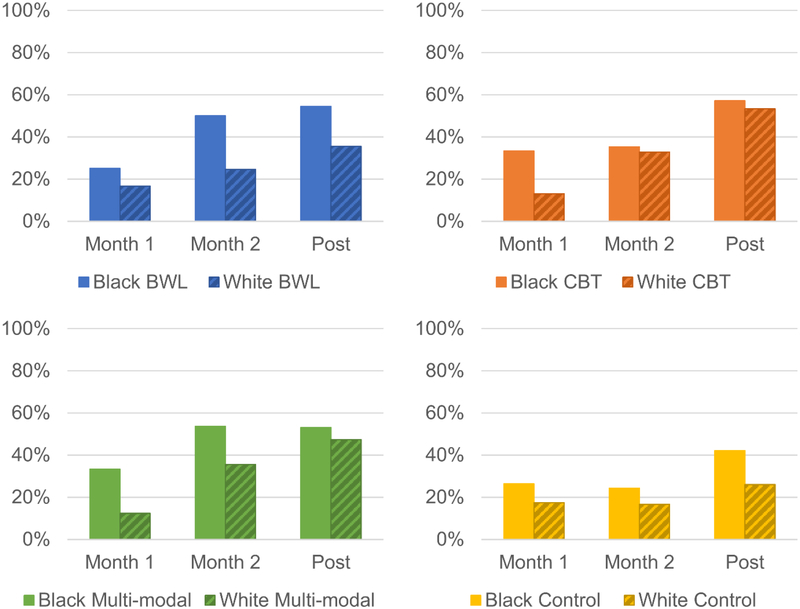

When binge-eating remission was examined categorically imputing failure for missing data, there were significant main effects of race (χ2(1)=7.01, p=.008) and time (χ2(2)=20.54, p<.0001). More Black patients than White patients achieved remission. Remission rates significantly increased over time with significant differences for all pairwise comparisons among time points.

Figure 2 depicts binge-eating remission by race, time, and treatment. When remission analyses were repeated using available data (i.e., to complement the intent-to-treat analyses using all enrolled patients with instances of missing data imputed as failure to achieve binge-eating remission), there were significant main effects of race (χ2(1)=5.81, p=.016) and time (χ2(2)=17.00, p<.001). Remission rates significantly increased over time with significant differences for all pairwise comparisons among time points. More Black patients than White patients achieved remission.

Figure 2.

Binge-eating Remission by Race, Treatment, and Time

* Omitted asterisks indicate non-significant difference between Black and White participants at each time point.

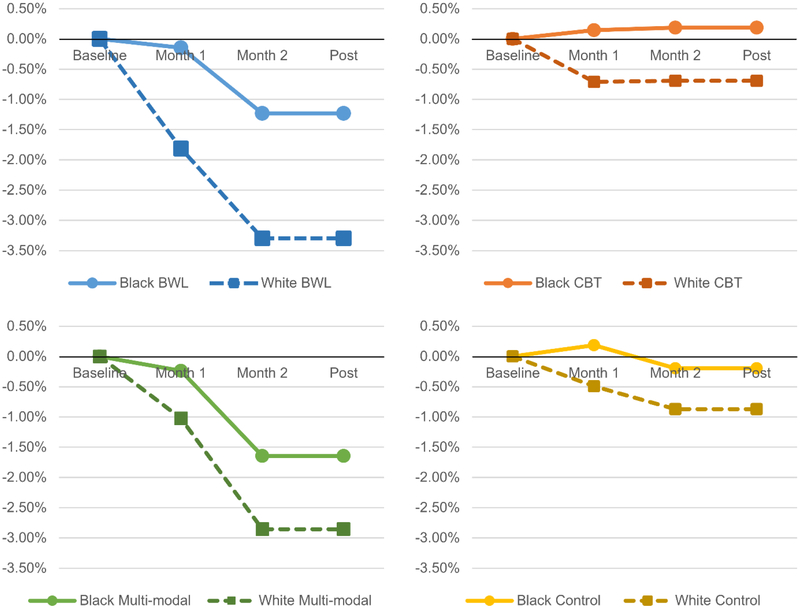

Percent Weight Loss

Figure 3 depicts mean percent weight loss by race, time, and treatment. There was no main effect of race (p=.079) and no interaction effects that involved race (ps>.909). There was a significant interaction between treatment and time (F6,482=6.42, p<.0001) as well as significant main effects of treatment (F3,343=12.33, p<.0001) and time (F2,498=20.97, p<.0001). Treatment differences were evident at all time points (p<.002) but were more pronounced at month 2 and post-treatment. In general, participants lost weight over time. BWL and multi-modal treatment produced significantly greater reductions in weight than CBT and control conditions, which did not result in significant weight loss.

Figure 3.

Percent Weight Loss by Race, Treatment, and Time

* Omitted asterisks indicate non-significant difference between Black and White participants at each time point.

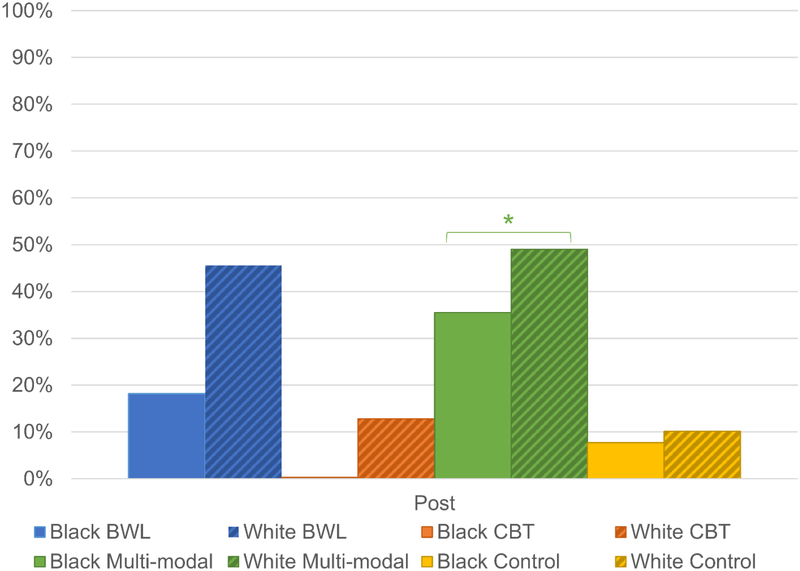

Weight change was also examined categorically at post-treatment, comparing all Black and White participants enrolled in different treatments on whether they achieved 5% weight loss; these analyses imputed failure for missing data. Race was significant (Fisher’s exact test p=.015): a greater proportion of White participants (28.9%, n=125) achieved 5% weight loss than Black participants (16.7%, n=16). Treatment was also significant (p<.001): a greater proportion of participants in BWL (37.5%, n=33) and multi-modal treatment (44.4%, n=84) achieved 5% weight loss than CBT (10.0%, n=14) or control conditions (9.0%, n=10). Treatment effects were significant within the Black (p=.004) and White (p<.001) groups. Among Black participants, multi-modal treatment was significantly more likely to produce 5% weight loss than CBT or control conditions, but not BWL. Among White participants, BWL and multi-modal treatment were significantly more likely to produce 5% weight loss than CBT or control conditions.

When 5% weight loss analyses were repeated using available data, the pattern of results remained unchanged. Race was significant (p=.005): a greater proportion of White participants (31.6%, n=125) achieved 5% weight loss than Black participants (17.2%, n=16). Treatment was also significant (p<.001): a greater proportion of participants in BWL (41.8%, n=33) and multi-modal treatment (46.7%, n=84) attained 5% weight loss than CBT (11.6%, n=14;) or control conditions (9.3%, n=10). Treatment effects were significant within the Black (p=.006) and White (p<.001) groups. Among Black participants, multi-modal treatment was significantly more likely to result in 5% weight loss than CBT or control conditions, but not BWL. Among White participants, BWL and multi-modal treatment were significantly more likely to result in 5% weight loss than CBT or control conditions. Figure 4 depicts 5% weight loss by race and treatment at post.

Figure 4.

Attainment of 5% Percent Weight Loss by Race and Treatment at Post

* Significant difference between Black and White participants, p<.05; omitted asterisks indicate non-significant difference between Black and White participants.

Eating-Disorder Psychopathology

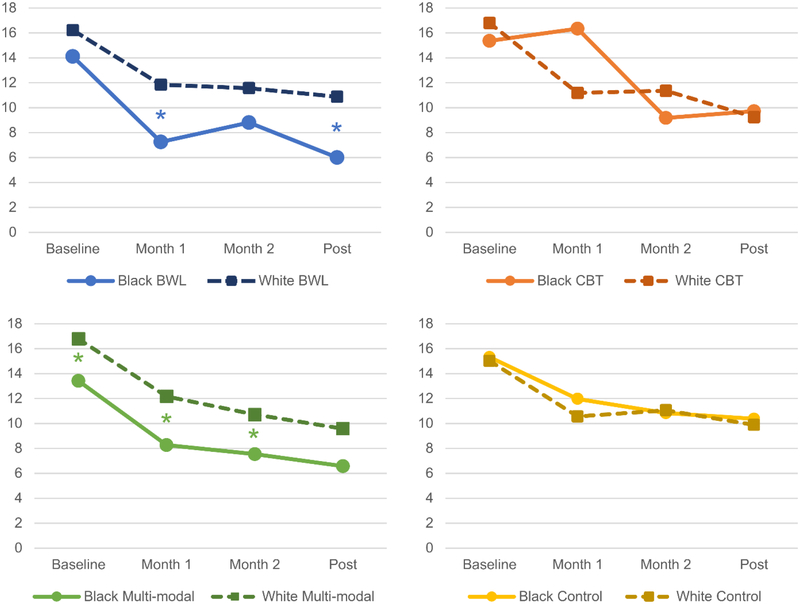

Figure 5 depicts eating-disorder psychopathology by race, time, and treatment. There was a trend towards a significant race by treatment by time interaction (F9,580=1.78, p=.070). However, post-hoc tests of effect slices revealed a significant treatment effect both among Black (F15,477=7.84, p<.0001) and White (F15,380=26.71, p<.0001) participants. Race did not have a significant main effect. The interaction of race by treatment and the interaction of race by time were not significant. There was a significant treatment by time interaction (F9,581=1.92, p=.047); however, there were no significant treatment differences at any individual time point and treatment did not have a significant main effect. There was a significant main effect of time (F3,549=84.82, p<.0001). In general, eating-disorder psychopathology decreased at each time point. This was not significantly more pronounced at any single time point.

Figure 5.

Eating-Disorder Psychopathology by Race, Treatment, and Time

* Omitted asterisks indicate non-significant difference between Black and White participants at each time point.

Depression Scores

Interactions among race, treatment, and time were all not significant. There was a significant main effect of race (F1,599=6.84, p=.009), such that White participants had higher depression scores than Black participants. There was also a significant main effect of time (F3,539=76.92, p<.0001). Treatment did not have a significant main effect. Depression scores significantly decreased over time; only the difference between scores at months 1 and 2 did not significantly differ. Figure 6 depicts depression scores by race, time, and treatment.

Figure 6.

Depression by Race, Treatment, and Time

* Significant difference between Black and White participants, p<.05; omitted asterisks indicate non-significant difference between Black and White participants.

Discussion

This study examined whether race moderated or predicted treatment outcomes among Black and White adults with BED enrolled in controlled clinical trials testing a variety of psychological and pharmacological treatments, alone and in combination, for BED. Overall, race did not moderate treatment effects for any treatment outcome. Race did have a main effect on binge-eating outcomes, both continuously and categorically: Black participants had fewer binge-eating episodes than White participants, and more Black participants achieved binge-eating remission than White participants. Although race did not significantly predict percent weight loss continuously, race did predict whether participants achieved 5% weight loss: more White participants than Black participants lost 5% of their baseline weight by post. Race also had a main effect on depression scores: Black participants had lower depression scores than White participants across time points. There were no significant associations of race with global eating-disorder severity. These findings indicate, as has been shown in earlier research focused on baseline (pre-treatment only) characteristics of patients with BED (Franko et al., 2012; Lydecker & Grilo, 2016), that although there are some racial differences in the clinical presentation of adults with BED, baseline differences in clinical presentation do not suggest the need for different treatments based on race.

As context for the findings related to race, we also note that the treatment findings in the current study are consistent with the literature on CBT (Grilo, 2017b; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017) and multi-modal treatment (Claudino et al., 2007; Ricca et al., 2001) for BED. CBT and multi-modal treatment produced significantly greater reductions in binge-eating episodes than control conditions, and BWL and multi-modal treatment produced significantly greater percent weight loss (and achievement of 5% weight loss) than CBT and control conditions. There were no significant main effects of treatment on eating-disorder psychopathology or depression scores. Findings highlight the need for awareness among clinicians about likely results of treatments and the need to inform patients about their treatment options. Although excess weight is not a defining feature of BED, obesity is associated strongly with BED (Udo & Grilo, 2018) and is often a reason that individuals seek treatment for BED (Brody, Masheb, & Grilo, 2005).

Our findings are largely consistent with those by Thompson-Brenner et al. (2013), which focused on CBT treatments using data pooled from BED treatment trials across different research sites. Treatments pooled in data from Thompson-Brenner et al. (2013) were primarily CBT approaches, and did not include any other possible treatments from the literature or any of the other treatments that we specifically examined in the present study (i.e., BWL, multi-modal treatments, or control conditions). Thompson-Brenner et al. (2013) also found that race was not a significant moderator for treatment effects across different forms of CBT. They also found minimal main effects of race, except that Black participants had lower eating-disorder psychopathology (i.e., global EDE/EDE-Q score) after treatment than White participants (albeit with a small effect size). Together, this converging evidence is important for clinical practice and clinical research. Black individuals with BED are less likely to seek treatment (Marques et al., 2011), and are underrepresented in clinical trials (Thompson-Brenner et al., 2013). Our findings – which suggest that Black patients can derive similar or better benefits from evidence-based treatments for BED although they may be less likely to lose a clinically-significant amount of weight – are encouraging for dissemination of BED treatments to racially-diverse patients. While a significantly lower proportion of Black participants attained a 5% weight loss than White participants, this one finding may have less clinical importance than the other outcome findings. As a group, Black participants lost an average amount of weight that was similar to the average weight lost by White participants, but a greater proportion of Black participants achieved binge-eating remission compared with White participants. Binge-eating remission appears to have “downstream” benefits for longer-term weight-loss maintenance (Chao et al., 2017; Yanovski, 2003). The binge-eating remission findings, coupled with similar improvements in global eating-disorder severity and depression between racial groups, provides strong support that evidence-based treatments for BED hold promise for diverse populations.

Additional research on reducing treatment-seeking disparities (Marques et al., 2011) is needed to improve access to these evidence-based treatments. In the weight-loss literature, there are similar findings that Black women lose less weight in behavioral treatments compared with White women, Black men, and White men; however, this pattern of differences does not appear to occur in pharmacological treatment (West, Prewitt, Bursac, & Felix, 2008). Future research should test whether Black patients with BED can be helped to attain greater weight loss that reaches a clinically-significant threshold from either more intensive or perhaps multi-modal treatment approaches.

Findings from Thompson-Brenner et al. (2013) and our study, which have similar sample sizes of Black (n=79 and n=113) participants, should be considered in conjunction with each other, as each has different strengths and limitations. Our findings pertain to participants who sought treatment for BED from a northeastern US medical school, delivered in the context of research studies. This study design allowed us to eliminate potential confounds due to geographic and site-specific differences that may exist in data pooled across sites. The clinical trials at our site used consistent study protocols, including consistent recruitment, eligibility determination, screening and assessment procedures, and clinician training, thus reducing a number of potential confounds.

Despite the strengths our research offers, there are limitations. We used a single-choice checklist to assess race; assessment using an open-ended, multi-choice, or continuous racial identity assessment may yield more information on race and BED. Additionally, larger samples that include other racial/ethnic groups and measures of socioeconomic status would allow for more comparisons that we were unable to evaluate. Our studies also had some relatively minimal exclusion criteria, primarily “safety-based” (e.g., medical instability was an exclusion), and most participants were well-educated. Thus, findings may not generalize to those with less education, to non-treatment-seeking individuals with BED, to those who seek treatment naturalistically in different clinical or medical settings (Marques et al., 2011), to those with more severe health (medically unstable) conditions, or to those who do not participate in research studies (Grilo, Lozano, & Masheb, 2005). Finally, our findings should be understood within the context of the methodological limitation inherent to an aggregated data analysis approach, namely, that randomization occurred within trials rather than across the entire sample.

Examining racial differences in the clinical presentation of adults with BED is important to inform and guide treatment and prevention efforts, including treatment dissemination. Further research is needed to improve understanding of specific treatment-related needs and the mechanisms by which treatments work. Future research should also examine other demographic and clinical factors to evaluate whether they influence treatment-seeking and whether they moderate treatment outcomes. Nonetheless, results from the current analyses importantly indicate that clinicians and clinical-researchers can have confidence that if they deliver evidence-based treatments for BED, both Black and White patients can benefit.

Public Health Significance:

This study indicates the importance of race in randomized controlled trials for binge-eating disorder. Among patients with binge-eating disorder who participated in treatment studies, some clinical improvements attained by Black and White patients were similar, including global eating-disorder severity and depression. Notably, a significantly greater proportion of Black participants achieved remission from binge eating, and a significantly lower proportion of Black participants lost a clinically-significant percentage of their starting weight, compared with White participants.

Funding:

This research was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health grants K24 DK070052 and R01 DK49587, American Heart Association, and Donaghue Medical Research Foundation. This paper does not reflect the views of the Public Health Service, NIH, AHA, nor the Donaghue Medical Research Foundation; funders played no role in the content of this paper.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: The authors (Lydecker, Gueorguieva, Masheb, White, Grilo) report no conflicts of interest. Drs. Grilo and Gueorguieva report several broader interests which did not influence this research or paper.

DSM-IV BED research criteria frequency (at least twice weekly) and duration (at least six months) stipulations for binge eating (American Psychiatric Association, 2004) are more stringent than those specified in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Thus, all participants meeting DSM-IV criteria also meet DSM-5 criteria.

Race was determined using a single-choice checklist item from the Questionnaire for Eating and Weight Problems (Yanovski, 1993). The full dataset also included potential participants who self-reported as Hispanic (n=39), or “Other” (n=26), but those respondents were excluded from the current analyses.

Sibutramine is a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, with some evidence that it produces weight loss and improvements in binge eating (Appolinario et al., 2003; Wilfley et al., 2008). Sibutramine was FDA-approved for obesity until 2010, when the manufacturer withdrew it from the market. Orlistat is a lipase inhibitor that reduces dietary fat absorption, with some evidence that it produces weight loss (e.g., Davidson et al., 1999). Fluoxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with some evidence supporting its use in BED (Marcus et al., 1990).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2004). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth, Text Revision ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Appolinario JC, Bacaltchuk J, Sichieri R, Claudino AM, Godoy-Matos A, Morgan C, … Coutinho W (2003). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sibutramine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 1109–1116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, & Steer R (1987). Manual for revised Beck Depression Inventory. New York: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Carbin MG (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Brody ML, Masheb RM, & Grilo CM (2005). Treatment preferences of patients with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 37, 352–356. doi: 10.1002/eat.20137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD (2000). The LEARN program for weight management. Dallas: American Health Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chao AM, Wadden TA, Gorin AA, Shaw Tronieri J, Pearl RL, Bakizada ZM, … Berkowitz RI (2017). Binge eating and weight loss outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes: 4-year results from the Look AHEAD study. Obesity, 25, 1830–1837. doi: 10.1002/oby.21975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudino AM, de Oliveira IR, Appolinario JC, Cordas TA, Duchesne M, Sichieri R, & Bacaltchuk J (2007). Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate plus cognitive-behavior therapy in binge-eating disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68, 1324–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MH, Hauptman J, DiGirolamo M, Foreyt JP, Halsted CH, Heber D, … Heymsfield SB (1999). Weight control and risk factor reduction in obese subjects treated for 2 years with orlistat: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 281, 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin MJ, Goldfein JA, Petkova E, Liu L, & Walsh BT (2007). Cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for binge eating disorder: Two-year follow-up. Obesity, 15, 1702–1709. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG (1995). Overcoming Binge Eating. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Beglin S (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16, 363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Cooper Z (1993). The Eating Disorder Examination In Fairburn CG & Wilson GT (Eds.), Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JBW (1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Clinician Version. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Thompson-Brenner H, Thompson DR, Boisseau CL, Davis A, Forbush KT, … Wilson GT (2012). Racial/ethnic differences in adults in randomized clinical trials of binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 186–195. doi: 10.1037/a0026700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DJ (1992). Beneficial health effects of modest weight loss. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 16, 397–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM (2017a). Behavioral weight loss vs stepped multi-modal treatment for binge eating disorder: Acute and longer-term 18-month outcomes. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51, S752–S753. [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM (2017b). Psychological and behavioral treatments for binge-eating disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78 Suppl 1, 20–24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.sh16003su1c.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Lozano C, & Masheb RM (2005). Ethnicity and sampling bias in binge eating disorder: Black women who seek treatment have different characteristics than those who do not. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 38, 257–262. doi: 10.1002/eat.20183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, & Masheb RM (2005). A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43, 1509–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, & Salant SL (2005). Cognitive behavioral therapy guided self-help and orlistat for the treatment of binge eating disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biological Psychiatry, 57, 1193–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, White MA, Gueorguieva R, Barnes RD, Walsh BT, … Garcia R (2014). Treatment of binge eating disorder in racially and ethnically diverse obese patients in primary care: Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of self-help and medication. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, & Wilson GT (2001a). A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, & Wilson GT (2001b). Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder: A replication. Obesity Research, 9, 418–422. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, & Wilson GT (2005). Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biological Psychiatry, 57, 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, & White MA (2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge-eating disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 675–685. doi: 10.1037/a0025049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Reas DL, & Mitchell JE (2016). Combining pharmacological and psychological treatments for binge eating disorder: Current status, limitations, and future directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 18, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0696-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, White MA, Gueorguieva R, Barnes RD, & Masheb RM (2013). Self-help for binge eating disorder in primary care: A randomized controlled trial with ethnically and racially diverse obese patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51, 855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Donato KA, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, … Yanovski SZ (2014). Guidelines (2013) for managing overweight and obesity in adults. Obesity, 22, S1–S410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, & Agras WS (2002). Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydecker JA, & Grilo CM (2016). Different yet similar: Examining race and ethnicity in treatment-seeking adults with binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84, 88–94. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydecker JA, White MA, & Grilo CM (2016). Black patients with binge-eating disorder: Comparison of different assessment methods. Psychological Assessment, 28, 1319–1324. doi: 10.1037/pas0000246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus MD, Wing RR, Ewing L, Kern E, McDermott M, & Gooding W (1990). A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine plus behavior modification in the treatment of obese binge-eaters and non-binge-eaters. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 876–881. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.7.876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques L, Alegria M, Becker AE, Chen CN, Fang A, Chosak A, & Diniz JB (2011). Comparative prevalence, correlates of impairment, and service utilization for eating disorders across US ethnic groups: Implications for reducing ethnic disparities in health care access for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44, 412–420. doi: 10.1002/eat.20787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL (2017). Pharmacologic Treatments for Binge-Eating Disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78 Suppl 1, 14–19. doi: 10.4088/JCP.sh16003su1c.03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2017). Eating disorders: recognition and treatment. NICE Guideline (NG69). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reas DL, & Grilo CM (2015). Pharmacological treatment of binge eating disorder: update review and synthesis. Expert Opinion in Pharmacotherapy, 16, 1463–1478. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.1053465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reas DL, Grilo CM, & Masheb RM (2006). Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire in patients with binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricca V, Mannucci E, Mezzani B, Moretti S, Di Bernardo M, Bertelli M, … Faravelli C (2001). Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine combined with individual cognitive-behaviour therapy in binge eating disorder: A one-year follow-up study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 70, 298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Brenner H, Franko DL, Thompson DR, Grilo CM, Boisseau CL, Roehrig JP, … Wilson GT (2013). Race/ethnicity, education, and treatment parameters as moderators and predictors of outcome in binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81, 710–721. doi: 10.1037/a0032946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo T, & Grilo CM (2018). Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5-defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Biological Psychiatry, 84, 345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadden TA, Foreyt JP, Foster GD, Hill JO, Klein S, O’Neil PM, … Dunayevich E (2011). Weight loss with naltrexone SR/bupropion SR combination therapy as an adjunct to behavior modification: the COR-BMOD trial. Obesity, 19, 110–120. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West DS, Prewitt TE, Bursac Z, & Felix HC (2008). Weight loss of black, white, and Hispanic men and women in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Obesity, 16, 1413–1420. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, Hudson JI, Mitchell JE, Berkowitz RI, Blakesley V, & Walsh BT (2008). Efficacy of sibutramine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized multicenter placebo-controlled double-blind study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 51–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06121970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, Spurrell EB, Cohen LR, Saelens BE, … Matt GE (2002). A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Grilo CM, & Vitousek KM (2007). Psychological treatment of eating disorders. American Psychologist, 62, 199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.62.3.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras WS, & Bryson SW (2010). Psychological treatments of binge eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 94–101. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, & Zandberg LJ (2012). Cognitive-behavioral guided self-help for eating disorders: effectiveness and scalability. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 343–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovski SZ (1993). Binge eating disorder: Current knowledge and future directions. Obesity Research, 1, 306–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovski SZ (2003). Binge eating disorder and obesity in 2003: Could treating an eating disorder have a positive effect on the obesity epidemic? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 34, S117–120. doi: 10.1002/eat.10211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]