Abstract

Background

HIV epidemiology among female sex workers (FSWs) and their clients in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is poorly understood. We addressed this gap through a comprehensive epidemiological assessment.

Methods

A systematic review of population size estimation and HIV prevalence studies was conducted and reported following PRISMA guidelines. Risk of bias (ROB) assessments were conducted for all included studies using various quality domains, as informed by Cochrane Collaboration guidelines. The pooled mean HIV prevalence was estimated using random-effects meta-analyses. Sources of heterogeneity and temporal trends were identified through meta-regressions.

Results

We identified 270 size estimation studies in FSWs and 42 in clients, and 485 HIV prevalence studies in 287,719 FSWs and 69 in 29,531 clients/proxy populations. Most studies had low ROB in multiple quality domains. The median proportion of reproductive-age women reporting current/recent sex work was 0.6% (range = 0.2–2.4%) and of men reporting currently/recently buying sex was 5.7% (range = 0.3–13.8%). HIV prevalence ranged from 0 to 70% in FSWs (median = 0.1%) and 0–34.6% in clients (median = 0.4%). The regional pooled mean HIV prevalence was 1.4% (95% CI = 1.1–1.8%) in FSWs and 0.4% (95% CI = 0.1–0.7%) in clients. Country-specific pooled prevalence was < 1% in most countries, 1–5% in North Africa and Somalia, 17.3% in South Sudan, and 17.9% in Djibouti. Meta-regressions identified strong subregional variations in prevalence. Compared to Eastern MENA, the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) ranged from 0.2 (95% CI = 0.1–0.4) in the Fertile Crescent to 45.4 (95% CI = 24.7–83.7) in the Horn of Africa. There was strong evidence for increasing prevalence post-2003; the odds increased by 15% per year (AOR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.09–1.21). There was also a large variability in sexual and injecting risk behaviors among FSWs within and across countries. Levels of HIV testing among FSWs were generally low. The median fraction of FSWs that tested for HIV in the past 12 months was 12.1% (range = 0.9–38.0%).

Conclusions

HIV epidemics among FSWs are emerging in MENA, and some have reached stable endemic levels, although still some countries have limited epidemic dynamics. The epidemic has been growing for over a decade, with strong regionalization and heterogeneity. HIV testing levels were far below the service coverage target of “UNAIDS 2016–2021 Strategy.”

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12916-019-1349-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: HIV, Sexually transmitted infections, Sex workers, Sex work, Prevalence, Incidence, Population size, Risk group size, Middle East and North Africa

Background

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is one of only two regions where HIV incidence and AIDS-related mortality are rising [1]. Between 2000 and 2015, the increase in the number of new infections was estimated at over a third, while that of AIDS-related deaths, at over threefold [1–3]. MENA has been described as “a real hole in terms of HIV/AIDS epidemiological data” [4], with unknown status and scale of epidemics in multiple countries [5–7].

Despite recent progress in HIV research and surveillance in MENA [8], including the conduct of integrated bio-behavioral surveillance surveys (IBBSS) [5, 9], many of these data are, at best, published in country-level reports, or never analyzed. Since 2007, the “MENA HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Synthesis Project” has maintained an active regional HIV database [6]. The first systematic syntheses of HIV data documented concentrated and emerging epidemics among men who have sex with men (MSM) [10] and people who inject drugs (PWID) [11]. The majority of these epidemics emerged within the last two decades [10, 11].

Although the size of commercial heterosexual sex networks is expected to be much larger than the risk networks of MSM and PWID [6, 7], estimates for the population proportion of female sex workers (FSWs), volume of clients they serve, and geographic and temporal trends in infection remain to be established. This evidence gap was highlighted in the latest gap report by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) [3], indicating “a lack of data on the burden of HIV among sex workers in the region” and stressing that “the epidemic among them is poorly understood” though “HIV in every country is expected to disproportionately affect sex workers” [3].

This study characterizes HIV epidemiology among FSWs and their clients in MENA by (1) systematically reviewing and synthesizing all available published and unpublished records documenting population size estimates, population proportions, HIV incidence, and HIV prevalence (including in proxy populations of clients such as male sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinic attendees); (2) estimating, for each population, the pooled mean HIV prevalence per country and regionally; (3) identifying the regional-level associations with prevalence, sources of heterogeneity, and temporal trends; and (4) synthesizing the key measures of sexual and injecting risk behaviors.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Evidence for population size estimate, population proportion, HIV incidence, and HIV prevalence in FSWs and clients was systematically reviewed as per Cochrane’s Collaboration guidelines [12]. Findings were reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13] (checklist in Additional file 1: Table S1). MENA definition here includes 23 countries extending from Pakistan to Morocco (Additional file 1: Figure S1), based on the convention in HIV research [6, 7, 10, 11] and on World Health Organization (WHO), UNAIDS, and World Bank definitions [6]. MENA was also classified by subregion comprising Eastern MENA (Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan), the Fertile Crescent (Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria), the Gulf (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen), the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Somalia, recently independent South Sudan), and North Africa (Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia).

Systematic searches were performed, up to July 29, 2018, on ten international-, regional-, and country-level databases; abstract archives of International AIDS Society conferences [14]; and Synthesis Project database which includes country-level and international organizations’ reports and routine data reporting [6, 7] (Additional file 1: Box S1). No language or year restrictions were used.

Titles and abstracts of unique citations were screened for relevance, and full texts of relevant/potentially relevant citations were retrieved for further screening. Any document/report including outcomes of interest based on primary data was eligible for inclusion. Case reports, case series, editorials, commentaries, and studies in populations (such as “vulnerable women”) where overlap with FSWs is implied but engagement in sex work is not explicitly indicated were excluded. Reference lists of reviews and all relevant documents were hand searched for eligible reports.

In this article, the term study refers to a specific outcome measure (population size estimate, incidence, or prevalence) in a specific population. Therefore, one report could contribute multiple studies, and one study could be published in different reports. Duplicate study results were included only once using the more detailed report.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction was performed by HC and double extraction by MH, with discrepancies settled by consensus or by contacting authors. Data were extracted from full texts by native speakers (extraction list in Additional file 1: Box S2).

Population size estimates and population proportions were grouped based on being of national coverage or for specific subnational settings, and distinguishing between current FSWs/clients and history of sex work/ex-client. For FSWs, population proportion is defined as the proportion of all reproductive-age women that are engaged in sex work, that is the exchange of sex for money (sex work as a profession) [15, 16], and for clients, as the proportion of men buying sex from FSWs using money. Studies with mixed or non-representative samples (samples biased towards oversampling FSWs with no estimate adjustment) were excluded.

Due to the paucity of studies directly looking at HIV prevalence in clients of FSW, HIV prevalence studies in male STI clinic attendees, or mixed-sex samples of predominantly men (> 60%), were used as a proxy for HIV prevalence in clients of FSWs [17, 18].

Based on meta-analysis results for the pooled HIV prevalence in FSWs, epidemics were classified as concentrated (prevalence > 5%), intermediate-intensity (prevalence between 1 and 5%), and low-level (prevalence < 1%), as informed by epidemiological relevance and existing conventions [19–21].

HIV incidence studies were identified and reported. Additional contextual information was extracted from FSW studies included in the review. These include age, age at sexual debut, age at sex work initiation, sex work duration, marital status, and HIV/AIDS knowledge and perception of risk, as well as behavioral measures of condom use, injecting drug use, sexual partnerships, and HIV testing.

Data were summarized using medians and ranges.

Quality assessment

Risk of bias (ROB) assessments for population size estimates/population proportions and for HIV prevalence were conducted as informed by Cochrane Collaboration guidelines [12] (criteria in Additional file 1: Table S2). Briefly, size estimation studies were classified as having “low” versus “high” ROB on each of the three domains assessing the (1) validity of sex work definition/engagement in paid sex (clear/valid definition; otherwise), (2) rigor of estimation methodology (likely-to-yield representative estimate; otherwise), and (3) response rate (≥ 60%; < 60%).

Prevalence studies were similarly classified on each of the four domains assessing the (1) validity of sex work definition/engagement in paid sex (clear/valid definition; otherwise), (2) rigor of sampling methodology (probability-based; non-probability-based), (3) response rate (≥ 60% or ≥ 60% of target sample size reached for studies using respondent-driven or time-location sampling; < 60%), and (4) type of HIV ascertainment (biological assays; self-report).

Studies with missing information for a specific domain were classified as having “unclear” ROB for that domain. Measures only extracted from routine databases were considered of unknown quality, as original reports were not available for assessing ROB, and were not included in the quality assessment. The impact of quality domains on observed prevalence was examined in meta-regression (described below).

Meta-analyses

Pooled mean HIV prevalence in FSWs and client populations were estimated using random-effects meta-analyses, by country and for the whole region. Variances were stabilized using Freeman-Tukey-type arcsine square-root transformation [22, 23]. Weighting was performed using the inverse-variance method [23, 24]. Pooling was performed using Dersimonian-Laird random-effects models to allow for sampling variation and true heterogeneity [25, 26]. Overall prevalence measures were replaced by their stratified measures where applicable.

Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q statistic to confirm the existence of heterogeneity, I2 to estimate the magnitude of between-study variation, and prediction intervals to estimate the 95% interval of distribution of true effect sizes [26, 27].

Meta-analyses were implemented in R version 3.4.2 [28].

Meta-regression analyses

Random-effects meta-regression analyses were conducted to identify the regional-level associations with HIV prevalence in FSWs, sources of between-study heterogeneity, and temporal trend. Independent variables considered a priori were country/subregion, FSW population type, sample size, median year of data collection, sampling methodology, response rate, validity of sex work definition, and HIV ascertainment (details in Additional file 1: Table S3). The same factors (as applicable) were considered for clients’ meta-regression analyses.

To avoid the exclusion of studies with zero prevalence, an increment of 0.1 was added to the number of events in all studies to calculate the log-transformed odds, that is prevalence/(1 − prevalence), and corresponding variance [29]. Factors showing strong evidence for an association with the odds (p value ≤ 0.10) in univariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis.

Meta-regressions were implemented in Stata/SE v.15.1 [30].

Results

Search results and scope of evidence

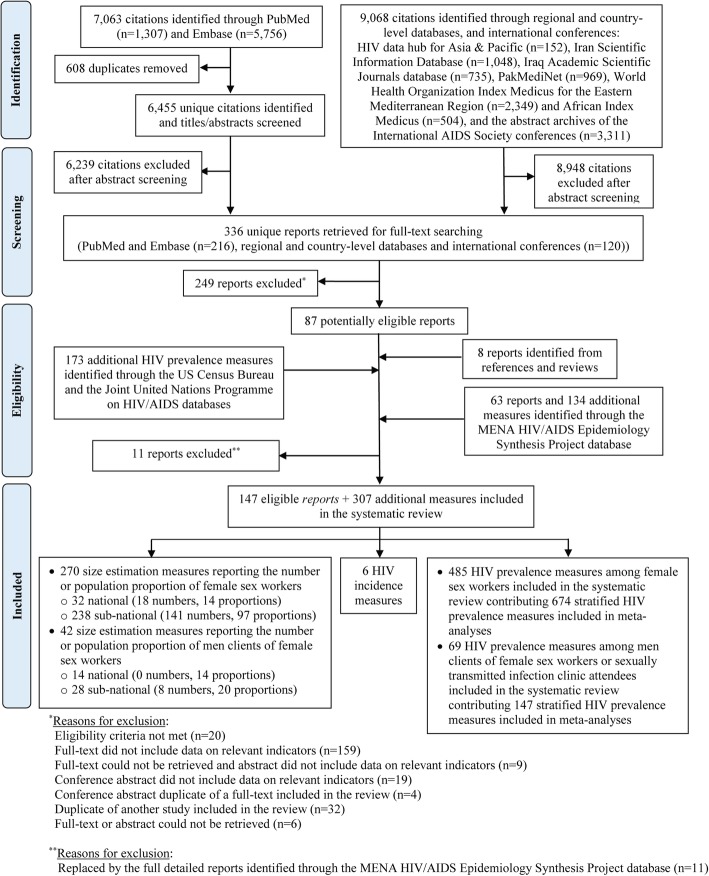

Figure 1 shows the study selection process. A total of 16,131 citations were identified through databases. After excluding duplicates and title and abstract screening, full texts of 336 unique citations were screened, and 87 reports were eligible for inclusion. Hand-searching of reference lists of relevant reports yielded eight additional eligible reports. Searching US Census Bureau and UNAIDS databases yielded 173 additional measures. Sixty-three detailed country-level reports, 11 of which replaced eligible articles, and 134 additional measures were further identified through Synthesis Project database. In sum, data from 147 eligible reports and 307 additional measures were included. These yielded in total 312 size estimation, 6 HIV incidence, and 554 HIV prevalence measures in FSWs and clients.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process in the systematic review following PRISMA guidelines [13]

Evidence for population size and/or population proportion of FSWs was available for 12 out of 23 MENA countries (270 studies). Population size/population proportion of clients was available in 42 studies from 10 countries. All 6 HIV incidence studies were among FSWs. A total of 485 HIV prevalence studies were identified in 287,719 FSWs from 17 countries and 69 HIV prevalence studies in 29,531 clients (or proxy populations) from 10 countries. Prevalence measures in FSWs and clients contributed respectively 674 and 147 stratified measures for the meta-analyses (overall prevalence measures were replaced by their strata in meta-analyses). For all types of measures, there was a high heterogeneity in data availability across countries.

Population size estimates and population proportions of FSWs and clients

Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S4 show the population size estimate and population proportion studies for FSWs and clients at the national and subnational levels, respectively. At the national level, the median number of current/recent FSWs (engaged in sex work in the past year) was 58,934 (range = 2218 in Djibouti to 167,501 in Pakistan), and the median population proportion (out of reproductive-age women aged 15–49 years) was 0.6% (range across studies = 0.2% in Egypt to 2.4% in Iran). The median population proportion of current/recent clients (buying sex from FSWs in the past year) based on diverse samples of general population men was 5.7% (range across studies = 0.3% in Sudan to 13.8% in Lebanon).

Table 1.

Estimates of some national representation for the number and population proportion of FSWs, and the number and population proportion of clients of FSWs, in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) reported by identified studies

| Country | Author, year [citation] | Year(s) of data collection | Estimation methodology | Sample type | Reported size estimate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time frame | N | Range | %* | Range* | ||||||

| FSWs | Egypt | Bahaa, 2010 [31] | 2004–2008 | Convenience sample (self-report) | Women seeking VCT testing | NR | NR | NR | 0.4 | NR |

| Jacobsen, 2014 [32] | 2014 | Enumeration (time-location geographical mapping) | FSWs in urban locations | Current | 22,986 | 6460–26,792 | 0.24 | NR | ||

| Djibouti | WHO, 2011 [33] | 2009 | NR | FSWs | NR | 1000 | NR | NR | NR | |

| WHO, 2011 [33] | 2011 | Capture-recapture | FSWs | Current | 2218 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Iran | WHO, 2011 [33] | 2010 | Network scale-up | General pop | Current | 80,000 | NR | NR | NR | |

| Sharifi, 2017 [34] | 2015 | Multiplier unique object | FSWs | Current | 19,800 | 10,900–38,100 | 0.31 | 0.17–0.58 | ||

| Sharifi, 2017 [34] | 2015 | Network scale-up | General pop | Current | 98,500 | 87,000–109,400 | 1.54 | 1.36–1.71 | ||

| Sharifi, 2017 [34] | 2015 | Wisdom of the crowds | FSWs | Current | 152,200 | 93,400–21,4300 | 2.38 | 1.46–3.35 | ||

| Lebanon | Kahhaleh, 2009 [35] | 1996 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | General pop (15–49 years) | Past 12 M | NR | NR | 0.54 | NR | |

| Kahhaleh, 2009 [35] | 2004 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | General pop (15–49 years) | Past 12 M | NR | NR | 0.53 | NR | ||

| Morocco | WHO, 2011 [33] | 2010 | NR | FSWs | Current | 67,000 | NR | NR | NR | |

| Bennani, 2013 [36] | 2011 | Multiplier unique object | FSWs | Past 6 M | 85,000 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| MOH, 2013 [37] | 2013 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | Young women (15–24 years) | Lifetime | NR | NR | 6.9 | NR | ||

| MOH, 2013 [37] | 2013 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | Young women (15–24 years) | Current | NR | NR | 2.4 | NR | ||

| Pakistan | NACP, 2005 [38] (round I) | 2005 | Enumeration (time-location geographical mapping) | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | Current | 35,050 | 30,300–39,800 | 0.78 | NR | |

| Emmanuel, 2010 [39] (round II) | 2006 | Enumeration (time-location geographical mapping) | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | Current | 167,501 | NR | 0.44 | NR | ||

| Emmanuel, 2013 [40, 41] (round IV) | 2011–2012 | Enumeration (time-location geographical mapping) | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | Current | 89,178 | 78,778–99,592 | 0.72 | NR | ||

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Enumeration (time-location geographical mapping) | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | Current | 64,829 | 57,734–70,428 | NR | NR | ||

| Sudan | AFROCENTER Group, 2005 [43] | 2005 | Self-report (convenience sample) | Young women | NR | NR | NR | 0.4 | NR | |

| Syria | WHO, 2011 [33] | 2011 | NR | FSWs | Current | 50,000 | NR | NR | NR | |

| Tunisia | WHO, 2011 [33] | 2005 | NR | FSWs | Current | NR | 1000–5000 | NR | NR | |

| WHO, 2011 [33] | 2009 | NR | FSWs | Current | 10,000 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| WHO, 2011 [33] | 2011 | NR | FSWs | Current | 25,500 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Yemen | MOH, 2010 [44] | NR | Enumeration (time-location geographical mapping) | FSWs | Current | 58,934 | NR | NR | 1.16–2.10 | |

| Clients of FSWs | Afghanistan | Todd, 2007 [45] | 2005–2006 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | TB patients receiving treatment | Lifetime | NR | NR | 3.57 | NR |

| Todd, 2012 [46] | 2010–2011 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | Army recruits | Lifetime | NR | NR | 12.5 | NR | ||

| Egypt | Bahaa, 2010 [31] | 2004–2008 | Convenience sample (self-report) | Men seeking VCT testing | NR | NR | NR | 0.9 | NR | |

| Lebanon | Kahhaleh, 2009 [35] | 1996 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | General pop (15–49 years) | Past 12 M | NR | NR | 9.7 | NR | |

| Adib, 2002 [47] | 1999 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | Military conscripts | Past 12 M | NR | NR | 13.84 | NR | ||

| Kahhaleh, 2009 [35] | 2004 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | General pop (15–49 years) | Past 12 M | NR | NR | 5.65 | NR | ||

| Morocco | MOH, 2007 [48] | 2007 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | Young men (15–24 years) | Lifetime | NR | NR | 35.3 | NR | |

| MOH, 2007 [48] | 2007 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | Young men (15–24 years) | Current | NR | NR | 2 | NR | ||

| MOH, 2013 [37] | 2013 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | Young men (15–24 years) | Lifetime | NR | NR | 10.5 | NR | ||

| MOH, 2013 [37] | 2013 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | Young men (15–24 years) | Current | NR | NR | 0.3 | NR | ||

| Pakistan | Mir, 2013 [49] | 2007 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | Urban men (16–45 years) | Lifetime | NR | NR | 11.9 | NR | |

| Mir, 2013 [49] | 2007 | Pop-based survey (self-report) | Urban men (16–45 years) | Past 12 M | NR | NR | 5.8 | NR | ||

| Sudan | NACP, 2004 [50] | 2004 | Convenience sample (self-report) | Military personnel | NR | NR | NR | 0.3 | NR | |

| AFROCENTER Group, 2005 [43] | 2005 | Convenience sample (self-report) | Young men | NR | NR | NR | 0.5 | NR | ||

The table is sorted by year(s) of data collection

Abbreviations: FSWs female sex workers, M months, MOH Ministry of Health, NACP National AIDS Control Programme, NR not reported, Pop population, TB tuberculosis, VCT voluntary counseling and testing, WHO World Health Organization

*The decimal places of the population proportion figures are as reported in the original reports

With high heterogeneity in estimation methodology, time frame, and scope between and within countries, it was deemed not meaningful to generate country-specific or regional-pooled estimates for the size/population proportions.

HIV incidence overview

There were six incidence studies among FSWs (three from each of Somalia and Djibouti; data not shown). Three studies reported zero seroconversions [51, 52]. One study from Somalia reported a cumulative incidence of 2.6% after 6 months of follow-up [51]. The other two from Djibouti—among predominantly Ethiopian FSWs (91%)—reported a cumulative incidence of 3.4% [51] and 11.6% [51] after 3 and 9 months of follow-up, respectively. All incidence studies were conducted before the year 2000 and were limited in scale and scope.

HIV prevalence overview

HIV prevalence in FSWs ranged from 0 to 70%, with a median of 0.1% (Tables 2 and 3 and Additional file 1: Table S5). There was a high heterogeneity, with almost half of the studies (46.8%) reporting zero prevalence. The median prevalence was 0% (range = 0–14%), 2.0% (range = 0–47.1%), and 18.8% (range = 0–70%) in countries with low-level (prevalence < 1%), intermediate-intensity (prevalence 1–5%), and concentrated epidemics (prevalence > 5%), respectively (epidemic classification based on the results of meta-analyses; see below and Table 5). Ranges indicated pockets of higher HIV prevalence, even in countries with low-level and intermediate-intensity epidemics.

Table 2.

HIV prevalence in FSWs in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), as reported in studies using probability-based sampling

| Country | Author, year [citation] | Year(s) of data collection | City/province | Study site | Sampling | Population | Sample size | HIV prevalence* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | ||||||||

| Afghanistan | SAR AIDS HDS, 2008 [53] | 2006–2007 | Jalalabad | Community | TLS | FSWs | 45 | 0 | NR |

| SAR AIDS HDS, 2008 [53] | 2006–2007 | Mazar-i-Sharif | Community | TLS | FSWs | 87 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2010 [54] (round I) | 2009 | Kabul | Community | RDS | FSWs | 368 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2012 [55] (round II) | 2012 | Herat | Community | RDS | FSWs | 344 | 0.9 | NR | |

| NACP, 2012 [55] (round II) | 2012 | Kabul | Community | RDS | FSWs | 333 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2012 [55] (round II) | 2012 | Mazar-i-Sharif | Community | RDS | FSWs | 355 | 0 | NR | |

| Egypt | MOH, 2006 [56] (round I) | 2006 | Cairo | Community | Conv** | FSWs | 118 | 0.8 | NR |

| MOH, 2010 [57] (round II) | 2010 | Cairo | Community | Conv** | FSWs | 200 | 0 | NR | |

| Iran | Navadeh, 2012 [58] | 2010 | Kerman | Community | RDS | FSWs | 139 | 0 | NR |

| Sajadi, 2013 [59] (round I) | 2010 | National | Facilities serving vulnerable women | MCS | FSWs | 817 | 4.5 | NR | |

| Kazerooni, 2014 [60] | 2010–2011 | Shiraz | Community | RDS | FSWs | 278 | 4.7 | NR | |

| Moaeyedi-Nia, 2016 [61] | 2012–2013 | Tehran | Community | RDS | FSWs | 161 | 5 | NR | |

| Mirzazadeh, 2016 [62] (round II) | 2015 | National | Facilities serving vulnerable women | MCS | FSWs | 1337 | 2.1 | 0.9–4.6 | |

| Karami, 2017 [63] | 2016 | Tehran | Community | TLS | FSWs | 369 | 4.6 | NR | |

| Jordan | WHO, 2011 [33] (round I) | 2009 | National | Community | RDS | FSWs | 225 | 0 | NR |

| MOH, 2014 [64] (round II) | 2013 | Amman | Community | RDS | FSWs | 358 | 0.6 | NR | |

| MOH, 2014 [64] (round II) | 2013 | Irbid | Community | RDS | FSWs | 102 | 0 | NR | |

| MOH, 2014 [64] (round II) | 2013 | Zarqa | Community | RDS | FSWs | 212 | 0.5 | NR | |

| Lebanon | Mahfoud, 2010 [65] | 2007–2008 | Greater Beirut | Community | RDS | FSWs | 95 | 0 | NR |

| Libya | Valadez, 2013 [66] (round I) | 2010–2011 | Tripoli | Community | RDS | FSWs | 69 | 15.7 | 3.2–32.6 |

| Morocco | MOH, 2012 [67] | 2011–2012 | Agadir | Community | RDS | FSWs | 364 | 5.1 | 2.1–8.6 |

| MOH, 2012 [67] | 2011–2012 | Fes | Community | RDS | FSWs | 359 | 1.8 | 0–2.1 | |

| MOH, 2012 [67] | 2011–2012 | Rabat | Community | RDS | FSWs | 392 | 0 | NR | |

| MOH, 2012 [67] | 2011–12 | Tanger | Community | RDS | FSWs | 319 | 1.4 | 0.4–3.3 | |

| Pakistan | Bokhari, 2007 [68] | 2004 | Lahore | Red-light district | SyCS | FSWs | 378 | 0.5 | NR |

| NACP, 2005 [38] (round I) | 2005 | Faisalabad | Community | RDS and TLS | Kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 400 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2005 [38] (round I) | 2005 | Hyderabad | Community | SyRS, RDS, and TLS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 400 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2005 [38] (round I) | 2005 | Karachi | Community | SyRS, RDS, and TLS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 400 | 0.8 | NR | |

| NACP, 2005 [38] (round I) | 2005 | Lahore | Community | SyRS, RDS, and TLS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 400 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2005 [38] (round I) | 2005 | Multan | Community | Conv (take all), RDS, and TLS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 400 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2005 [38] (round I) | 2005 | Peshawar | Community | MCS | Kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 359 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2005 [38] (round I) | 2005 | Quetta | Community | RDS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 411 | 0.7 | NR | |

| NACP, 2005 [38] (round I) | 2005 | Sukkur | Community | RDS and TLS | Kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 368 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Bannu | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 194 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Faisalabad | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 400 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Gujranwala | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 400 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Hyderabad | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 398 | 0.3 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Karachi | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 403 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Lahore | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 425 | 0.02 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Larkana | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 400 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Multan | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, and street-based FSWs | 400 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Peshawar | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 423 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Quetta | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 398 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Sargodha | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 400 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2007 [69] (round II) | 2006 | Sukkur | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 400 | 0 | NR | |

| Hawkes, 2009 [70] | 2007 | Abbottabad | Community | RDS | FSWs | 107 | 0 | NR | |

| Hawkes, 2009 [70] | 2007 | Rawalpindi | Community | RDS | FSWs | 426 | 0 | NR | |

| Khan, 2011 [71] | 2007 | Lahore | Community | RDS | FSWs | 730 | 0.7 | NR | |

| NACP, 2010 [72] (special IBBSS among FSWs) | 2009 | Punjab and Sindh | Community | SyRS and MCS | FSWs | 2197 | 1.0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | DG Khan | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 375 | 0.5 | 0.1–1.9 | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | Faisalabad | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 376 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | Haripur | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 211 | 0.9 | 0.3–3.4 | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | Karachi | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 377 | 1.9 | 0.9–3.8 | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | Lahore | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 375 | 0.5 | 0.1–1.9 | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | Larkana | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 375 | 1.9 | 0.9–3.8 | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | Multan | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 375 | 0.3 | 0.05–1.5 | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | Peshawar | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 367 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | Quetta | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 345 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | Rawalpindi | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 375 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | Sargodha | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 345 | 0.3 | 0.05–1.6 | |

| NACP, 2012 [40] (round IV) | 2012 | Sukkur | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 375 | 0.8 | 0.3–2.3 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Bahawalpur | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 351 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Bannu | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 196 | 1.5 | 1–4.4 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | DG Khan | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 364 | 0.8 | 0.3–2.4 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Gujranwala | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 304 | 0.7 | 0.2–2.4 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Gujrat | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 250 | 0.4 | 0.1–2.2 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Hyderabad | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 364 | 2.2 | 1.1–4.3 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Karachi | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 387 | 2.6 | 1.4–4.7 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Kasur | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 364 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Larkana | Community | SyRS and MCS | Brothel, kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 364 | 4.1 | 2.5–6.7 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Mirpurkhas | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 364 | 4.1 | 2.5–6.7 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Nawabshah | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 364 | 3.8 | 2.3–6.4 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Peshawar | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 265 | 3 | 1.5–5.8 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Quetta | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 364 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Rawalpindi | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 364 | 0.3 | 0.1–1.5 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Sheikhupura | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 363 | 1.7 | 1.1–4.9 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Sialkot | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 193 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Sukkur | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 364 | 8.8 | 6.3–12.2 | |

| NACP, 2017 [42] (round V) | 2016–2017 | Turbat | Community | SyRS and MCS | Kothikhana, home, street-based, and other FSWs | 72 | 0 | NR | |

| Somalia | Testa, 2008 [73] (round I) | 2008 | Hargeisa | Community | RDS | FSWs | 237 | 5.2 | 2.5–8.5 |

| IOM, 2017 [74] (round II) | 2014 | Hargeisa | Community | RDS | FSWs | 96 | 4.8 | 0.2–9.3 | |

| Sudan | Elkarim, 2002 [75] | 2002 | National | Community | MSysRS | FSWs | 367 | 4.4 | NR |

| Abdelrahim, 2010 [76] | 2008 | Khartoum | Community | RDS | FSWs | 321 | 0.9 | 0.1–2.2 | |

| NACP, 2010 [77] | 2008–09 | Gezira | Community | RDS | FSWs | 267 | 0.1 | NR | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | Alshamalia | Community | RDS | FSWs | 305 | 0.3 | 0–1 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | Blue Nile | Community | RDS | FSWs | 279 | 1.5 | 0–3 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | Gadarif | Community | RDS | FSWs | 282 | 0.6 | 0–1 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | Gezira | Community | RDS | FSWs | 296 | 0.7 | 0–1 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | Kassala | Community | RDS | FSWs | 288 | 5.0 | 2–8 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | Khartoum | Community | RDS | FSWs | 287 | 0 | NR | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | North Darfur | Community | RDS | FSWs | 303 | 0.7 | 0–3 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | North Kordofan | Community | RDS | FSWs | 296 | 1 | 0–3 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | Red Sea | Community | RDS | FSWs | 293 | 7.7 | 4–12 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | River Nile | Community | RDS | FSWs | 291 | 0.7 | 0–2 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | Sinnar | Community | RDS | FSWs | 303 | 0.7 | 0–2 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | South Darfur | Community | RDS | FSWs | 299 | 0.2 | 0–1 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | West Darfur | Community | RDS | FSWs | 284 | 1 | 0–3 | |

| NACP, 2012 [78] | 2011 | White Nile | Community | RDS | FSWs | 288 | 1.3 | 0–3 | |

| MOH, 2016 [79] | 2015–2016 | Juba, South Sudan | Community | RDS | FSWs | 835 | 37.9 | 33.6–42.2 | |

| Tunisia | Hsairi, 2012 [80] | 2009 | Tunis, Sfax, and Sousse | Community | RDS | Street-based FSWs | 703 | 0.4 | NR |

| Hsairi, 2012 [80] | 2011 | Tunis | Community | TLS | Street-based FSWs | 357 | 0.6 | 0–1.3 | |

| Hsairi, 2012 [80] | 2011 | Sfax | Community | TLS | Street-based FSWs | 284 | 0 | NR | |

| Hsairi, 2012 [80] | 2011 | Sousse | Community | TLS | Street-based FSWs | 347 | 1.2 | 0.02–2.3 | |

| Yemen | Stulhofer, 2008 [81] (round I) | 2008 | Aden | Community | RDS | FSWs | 244 | 1.3 | 0–2.9 |

| MOH, 2014 [82] (round I) | 2010–2011 | Hodeida | Community | RDS | FSWs | 301 | 0 | NR | |

The table is sorted by year(s) of data collection

Abbreviations: CI confidence interval, Conv convenience, FSWs female sex workers, IBBSS integrated bio-behavioral surveillance survey, IOM International Organization for Migration, MCS multistage cluster sampling, MOH Ministry of Health, MSyRS multistage systematic random sampling, NACP National AIDS Control Programme, NR not reported, RDS respondent-driven sampling, SAR AIDS HDS South Asia Region AIDS Human Development Sector, SyCS systematic cluster sampling, SyRS systematic random sampling, TLS time-location sampling, WHO World Health Organization

*The decimal places of the prevalence figures are as reported in the original reports, but prevalence figures with more than one decimal places were rounded to one decimal place, with the exception of those below 0.1%. Most studies did not report the 95% CIs associated with prevalence

**Integrated bio-behavioral surveillance survey with sampling initially planned as respondent-driven but ended up being a convenience for logistical reasons

Table 3.

HIV prevalence in FSWs in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), as reported in studies using non-probability sampling

| Country | Author, year [citation] | Year(s) of data collection | City/province | Study site | Sampling | Population | Sample size | HIV prevalence* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | ||||||||

| Afghanistan | Todd, 2010 [83] | 2006–2008 | Jalalabad, Kabul, and Mazar-i-Sharif | Community and NGO | Conv | FSWs | 520 | 0.2 | 0.01–1.1 |

| Djibouti | Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1987 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | Street-based FSWs | 66 | 4.6 | NR |

| Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1987 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | Bar hostesses | 221 | 1.4 | NR | |

| Constantine, 1992 [52] | 1988 | Djibouti | NR | Conv | FSWs | 33 | 18.2 | NR | |

| Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1988 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | Street-based FSWs | 78 | 9.0 | NR | |

| Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1988 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | Bar hostesses | 255 | 2.7 | NR | |

| Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1990 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | Street-based FSWs | 116 | 41.7 | NR | |

| Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1990 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | Bar hostesses | 180 | 5.0 | NR | |

| Couzineau, 1991 [85] | 1991 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | Street-based FSWs | 300 | 43 | NR | |

| Couzineau, 1991 [85] | 1991 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | Bar girls | 397 | 13.1 | NR | |

| Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1991 | Djibouti | STI clinic and residences | Conv | Street-based FSWs | 292 | 36.0 | NR | |

| Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1991 | Djibouti | STI clinic and residences | Conv | Bar hostesses | 360 | 15.3 | NR | |

| Philippon, 1997 [86] | 1995 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | Street-based FSWs | 176 | 49 | NR | |

| Marcelin, 2002 [87] | 1998–1999 | Djibouti | STI clinics | Conv | Street-based FSWs | 43 | 70 | NR | |

| Marcelin, 2002 [87] | 1998–1999 | Djibouti | STI clinics | Conv | FSWs working in luxury bars | 123 | 7 | NR | |

| Egypt | Sheba, 1988 [88] | 1986–1987 | Multiple cities | NR | Conv | FSWs | 87 | 0 | NR |

| Watts, 1993 [89] | 1986–1990 | Urban areas | Medical facilities | Conv | FSWs | 349 | 0 | NR | |

| Kabbash, 2012 [90] | 2009–2010 | Greater Cairo | Community | Conv | FSWs | 431 | 0 | NR | |

| Iran | Jahani, 2005 [91] | 2002 | NR | Detainment center/prison | Conv | FSWs detained by the police | 149 | 0 | NR |

| Kassaian, 2012 [92] | 2009–2010 | Isfahan | Prison, drop-in centers, and community | Conv | FSWs | 91 | 0 | NR | |

| Taghizadeh, 2015 [93] | 2014 | Sari, Mazandaran | Drop-in center | Conv | FSWs at a drop-in center | 184 | 4 | NR | |

| Asadi-Ali, 2018 [94] | 2015 | Northern Iran | Counseling center, drop-in center, and community | Conv | FSWs | 133 | 1.5 | NR | |

| Lebanon | Naman, 1989 [95] | 1985–1987 | NR | NR | Conv | FSWs | 291 | 0.3 | NR |

| Morocco | MOH, 2008 [96] | 2007 | Agadir, Rabat/Sale, Tanger | NGO clinic | Conv | FSWs presenting for consultation | 141 | 1.4 | 0.1–2.5 |

| Pakistan | Iqbal, 1996 [97] | 1987–1994 | Lahore | Hospital | Conv | FSWs | 21 | 0 | NR |

| Baqi, 1998 [98] | 1993–1994 | Karachi | VCT | Conv | FSWs in red-light district | 77 | 0 | NR | |

| Anwar, 1998 [99] | NR | Lahore | NR | NR | FSWs | 103 | 1.9 | NR | |

| Bokhari, 2007 [68] | 2004 | Karachi | Community | Snowball | FSWs in red-light district | 421 | 0 | NR | |

| Shah, 2004 [100] | 2004 | Hyderabad | Community | Conv | FSWs | 157 | 0 | NR | |

| Shah, 2004 [101] | 2004 | Sindh | Sentinel surveillance | Conv | FSWs | 163 | 1.2 | NR | |

| Akhtar, 2008 [102] | 2007 | Faisalabad | Community | NR | FSWs | 246 | 0 | NR | |

| Raza, 2015 [103] | 2014 | Rawalpindi | Clinics | Conv | FSWs | NR | 0 | NR | |

| Somalia | Jama, 1987 [104] | 1985–1986 | Mogadishu | Camp | Conv | FSWs attending health education program | 85 | 0 | NR |

| Burans, 1990 [105] | NR | Mogadishu | NR | Conv | FSWs | 89 | 0 | NR | |

| Scott, 1991 [106] | 1989 | Merka, Kismayu | NR | Conv | FSWs | 57 | 0 | NR | |

| Corwin, 1991 [107] | 1990 | Chismayu, Merca, Mogadishu | NR | Conv | FSWs | 302 | 3 | NR | |

| Jama Ahmed, 1991 [51] | 1991 | Mogadishu | PHC | Conv | FSWs | 155 | 0.6 | NR | |

| Sudan | Burans, 1990 [108] | 1987 | Port Sudan | NR | Conv | FSWs | 203 | 0 | NR |

| McCarthy, 1995 [109] | NR | Juba, South Sudan | NR | Conv | FSWs | 50 | 16 | NR | |

| Tunisia | Bchir, 1988 [110] | 1987 | Sousse | NR | Conv | FSWs | 42 | 0 | NR |

| Hassen, 2003 [111] | NR | Sousse | PHC | Conv | Legal FSWs | 51 | 0 | NR | |

| Znazen, 2010 [112] | 2007 | Tunis, Sousse, and Gabes | Medical facilities | Conv | Legal FSWs undergoing routine testing | 183 | 0 | NR | |

The table is sorted by year(s) of data collection or year of publication if the year of data collection was not reported

Abbreviations: CI confidence interval, Conv convenience, FSWs female sex workers, MOH Ministry of Health, NGO non-governmental organization, NR not reported, PHC primary healthcare centers, STI sexually transmitted infection, VCT voluntary counseling and testing

*The decimal places of the prevalence figures are as reported in the original reports, but prevalence figures with more than one decimal places were rounded to one decimal place, with the exception of those below 0.1%. Most studies did not report the 95% CIs associated with prevalence

Table 5.

Results of meta-analyses on studies reporting HIV prevalence in FSWs and their clients (or proxy populations of clients such as male STI clinic attendees) in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) by epidemic type

| Country | Studies (N) | Samples | HIV prevalence | Pooled mean HIV prevalence** | Heterogeneity measures | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tested | HIV positive | Median* (%) | Range* (%) | % | 95% CI | Q (p value)† | I2‡ (%; 95% CI) | Prediction interval£ (95%) | ||||

| FSWs | Low-level⁑ | Afghanistan | 9 | 3578 | 7 | 0 | 0–0.90 | 0.03 | 0.00–0.18 | 7.59 (p = 0.4744) | 0.0 (0.0–62.9) | 0.00–0.22 |

| Bahrain | 1 | 724 | 6 | 0.83 | – | 0.83¥ | 0.30–1.80 | – | – | – | ||

| Egypt | 33 | 7222 | 16 | 0 | 0–1.49 | 0.03 | 0.00–0.14 | 36.26 (p = 0.2765) | 12.8 (0.0–43.4) | 0.00–0.34 | ||

| Iran | 32 | 17,277 | 211 | 0.02 | 0–14.00 | 0.99 | 0.34–1.88 | 569.63 (p < 0.0001) | 94.6 (93.2–95.6) | 0.00–8.84 | ||

| Iraq | 29 | 15,852 | 1 | 0 | 0–0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | 6.24 (p = 1.0000) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.00–0.00 | ||

| Jordan | 7 | 1024 | 4 | 0 | 0–1.33 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.31 | 3.43 (p = 0.7537) | 0.0 (0.0–48.9) | 0.00–0.48 | ||

| Lebanon | 11 | 11,589 | 12 | 0.07 | 0–2.40 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.07 | 18.82 (p = 0.0426) | 46.9 (0.0–73.6) | 0.00–0.33 | ||

| Pakistan | 81 | 26,678 | 217 | 0 | 0–8.80 | 0.35 | 0.18–0.57 | 368.57 (p < 0.0001) | 78.3 (73.3–82.3) | 0.00–3.06 | ||

| Syria | 56 | 97,071 | 12 | 0 | 0–0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | 32.37 (p = 0.9936) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.00–0.00 | ||

| Tunisia | 53 | 22,224 | 59 | 0 | 0–2.30 | 0.02 | 0.00–0.11 | 124.81 (p < 0.0001) | 58.3 (43.6–69.2) | 0.00–0.89 | ||

| Yemen | 10 | 1767 | 34 | 0.25 | 0–7.00 | 0.82 | 0.00–2.91 | 63.01 (p < 0.0001) | 85.7 (75.6–91.7) | 0.00–11.67 | ||

| Intermediate-intensity⁑ | Algeria | 33 | 4241 | 179 | 2.00 | 0–20.00 | 2.39 | 1.02–4.15 | 215.22 (p < 0.0001) | 85.1 (80.1–88.9) | 0.00–15.05 | |

| Libya | 4 | 1249 | 28 | 8.43 | 1.08–18.18 | 4.86 | 0.81–11.37 | 34.41 (p < 0.0001) | 91.3 (80.8–96.0) | 0.00–47.09 | ||

| Morocco | 200 | 40,507 | 804 | 1.07 | 0–52.90 | 1.11 | 0.83–1.41 | 851.66 (p < 0.0001) | 76.6 (73.3–79.6) | 0.00–5.98 | ||

| Somalia | 17 | 2015 | 57 | 0.35 | 0–47.06 | 1.64 | 0.42–3.39 | 61.50 (p < 0.0001) | 74.0 (57.7–83.8) | 0.00–10.24 | ||

| Sudan€ | 22 | 7207 | 128 | 0.95 | 0–7.70 | 1.30 | 0.76–1.96 | 98.06 (p < 0.0001) | 78.6 (68.1–85.6) | 0.00–5.26 | ||

| Concentrated ⁑ | Djibouti | 68 | 22,028 | 4618 | 18.75 | 0–70.00 | 17.89 | 13.62–22.60 | 5127.36 (p < 0.0001) | 98.7 (98.6–98.8) | 0.00–63.91 | |

| South Sudan | 8 | 5466 | 1108 | 18.50 | 2.82–37.90 | 17.32 | 8.66–28.14 | 554.81 (p < 0.0001) | 98.7 (98.3–99.1) | 0.00–61.99 | ||

| All countries | 674 | 287,719 | 7501 | 0.26 | 0–70.00 | 1.44 | 1.14–1.76 | 24,605.29 (p < 0.0001) | 97.3 (97.2–97.4) | 0.00–16.49 | ||

| Clients of FSWs | Low-level⁑ | Egypt | 6 | 1362 | 3 | 0.17 | 0–0.80 | 0.09 | 0.00–0.42 | 4.82 (p = 0.4386) | 0.0 (0.0–73.7) | 0.00–0.60 |

| Kuwait | 6 | 6505 | 1 | 0 | 0–0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.04 | 0.36 (p = 0.9963) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.00–0.07 | ||

| Pakistan | 12 | 6498 | 9 | 0 | 0–1.10 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.10 | 14.93 (p = 0.1857) | 26.3 (0.0–62.6) | 0.00–0.42 | ||

| Yemen | 1 | 30 | 0 | 0 | – | 0.00¥ | 0.00–11.57 | – | – | – | ||

| Intermediate-intensity⁑ | Algeria | 7 | 728 | 22 | 7.29 | 0–25.80 | 3.51 | 0.32–8.90 | 39.79 (p < 0.0001) | 84.9 (70.8–92.2) | 0.00–27.63 | |

| Morocco | 84 | 10,348 | 47 | 0 | 0–8.00 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.05 | 76.30 (p = 0.6854) | 0.0 (0.0–19.9) | 0.00–0.05 | ||

| Somalia | 11 | 1010 | 21 | 0.94 | 0–9.62 | 1.38 | 0.25–3.11 | 25.74 (p = 0.0041) | 61.1 (25.0–79.9) | 0.00–8.46 | ||

| Sudan€ | 4 | 791 | 14 | 1.61 | 0–2.51 | 1.22 | 0.16–2.97 | 7.02 (p = 0.0711) | 57.3 (0.0–85.8) | 0.00–11.65 | ||

| Concentrated⁑ | Djibouti | 15 | 2222 | 217 | 2.20 | 0–34.60 | 5.36 | 1.53–10.81 | 244.98 (p < 0.0001) | 94.3 (92.0–95.9) | 0.00–35.23 | |

| South Sudan | 1 | 37 | 5 | 13.5 | – | 13.5¥ | 4.54–28.77 | – | – | – | ||

| All countries | 147 | 29,531 | 339 | 0 | 0–34.60 | 0.38 | 0.14–0.71 | 977.96 (p < 0.0001) | 85.1 (82.9–87.0) | 0.00–6.60 | ||

Abbreviations: CI confidence interval, FSWs female sex workers

*These medians and ranges are calculated on the stratified HIV prevalence measures

**Missing sample sizes for measures (or their strata) were imputed using median sample size calculated from studies with available information. Analyses excluding these studies had no impact on study findings

†Q—the Cochran’s Q statistic is a measure assessing the existence of heterogeneity in effect size (here, HIV prevalence) across studies

‡I2—a measure assessing the magnitude of between-study variation that is due to the differences in effect size (here, HIV prevalence) across studies rather than chance

£Prediction interval—a measure estimating the 95% interval of the distribution of true effect sizes (here, HIV prevalence)

⁑Based on results of meta-analyses for FSWs, countries were classified as having low-level HIV epidemic (prevalence < 1%), intermediate-intensity HIV epidemic (prevalence 1–5%), and concentrated HIV epidemic (prevalence > 5%)

¥Point estimate as only one study was available

€Before 2011, South Sudan was part of Sudan, and thus, earlier measures from Sudan were based on studies that may have included participants from both Sudan and South Sudan

In clients/male STI clinic attendees, HIV prevalence ranged from 0 to 34.6%, with a median of 0.4% (Table 4). Studies also showed high heterogeneity with 37.7% reporting zero prevalence. The median prevalence was 0% (range = 0–1.1%), 0.6% (range = 0–9.6%), and 7.4% (range = 0.8–34.6%) in countries with low-level, intermediate-intensity, and concentrated epidemics, respectively. Ranges indicated pockets of higher HIV prevalence in countries with intermediate-intensity epidemics.

Table 4.

HIV prevalence in clients of FSWs (or proxy populations of clients of FSWs such as male STI clinic attendees) in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

| Country | Author, year [citation] | Year(s) of data collection | City/province | Study site | Sampling | Population | Sample size | HIV prev* | Sexual contacts | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | |||||||||

| Algeria | MOH, 2009 [113] | 2004 | Oran | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 41 | 4.9 | NR | NR |

| MOH, 2009 [113] | 2004 | Tamanrasset | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 105 | 0 | 0 | NR | |

| MOH, 2009 [113] | 2004 | Tizi-Ouzou | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 11 | 9.1 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 2009 [113] | 2007 | National | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 571 | 3.3 | NR | NR | |

| Djibouti | Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1987 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 252 | 0.8 | NR | NR |

| Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1988 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 249 | 0.8 | NR | NR | |

| Fox, 1989 [114] | NR | NR | NR | Conv | Clients of FSWs | 105 | 1.0 | NR | Clients of FSWs | |

| Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1990 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 106 | 1.9 | NR | NR | |

| OMS, 2001 [115] | 1990 | NR | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | NR | 2.2 | NR | NR | |

| Rodier, 1993 [84] | 1991 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 193 | 10.4 | NR | NR | |

| OMS, 2001 [115] | 1991 | NR | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | NR | 9.2 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 1993 [116] | 1992 | NR | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | NR | 11.6 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 1993 [116] | 1993 | NR | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 411 | 14.4 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 2002 [117] | 2001–2002 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 237 | 34.6 | NR | NR | |

| Bortolotti, 2007 [6, 118] | 2006 | Djibouti | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 72 | 5.6 | 1.5–13.6 | NR | |

| Egypt | Sheba, 1988 [88] | 1986–1987 | Multiple cities | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 302 | 0 | NR | NR |

| Sadek, 1991 [119] | 1987–1988 | Cairo | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 140 | 0.7 | NR | NR | |

| Sadek, 1991 [119] | 1989–1990 | Cairo | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 125 | 0.8 | NR | NR | |

| Fox, 1994 [120] | 1993 | Alexandria | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 200 | 0 | NR | NR | |

| Fox, 1994 [120] | 1993 | Cairo | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 300 | 0.3 | NR | NR | |

| Saleh, 2000 [121] | 1998–2000 | Alexandria | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 295 | 0 | NR | NR | |

| Kuwait | NAP, 1999 [122] | 1984–1998 | Sabah, Kuwait | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 3097 | 0.02 | NR | NR |

| Murzi, 1989 [123] | 1988 | Kuwait | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 305 | 0 | NR | NR | |

| Al-Owaish, 2000 [124] | 1996–1997 | Kuwait | STI clinic | SyRS | STI clinic attendees (Kuwaiti) | 617 | 0 | NR | 23% reported contact with FSWs, 1% with MSWs, 35% with girlfriend, 12% with a mix of the above | |

| Al-Owaish, 2000 [124] | 1996–1997 | Kuwait | STI clinic | SyRS | STI clinic attendees (non-Kuwaiti) | 1367 | 0 | NR | 61% reported contact with FSWs, 0.5% with MSWs, 28.5% with girlfriend, 3% with a mix of the above | |

| Al-Owaish, 2002 [125] | 2002 | Kuwait | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees (non-Kuwaiti) | 599 | 0 | NR | NR | |

| Al-Mutairi, 2007 [126] | 2003–2004 | Kuwait | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees (predom. men) | 520 | 0 | NR | 79% reported contact with FSWs | |

| Morocco | Heikel, 1999 [127] | 1992–1996 | Casablanca | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 1131 | 0.9 | NR | NR |

| Manhart, 1996 [128] | 1996 | Agadir, Tanger, and Marrakech | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 223 | 1.4 | NR | NR | |

| Alami, 2002 [129] | 2001 | Rabat, Sale, Beni Mellal, and Marrakech | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 422 | 0 | NR | 70.7% reported new sexual partner, 47% multiple sexual partners in the past 3 months | |

| MOH, 2001 [130] | 2001 | Marrakech, Beni Mellal, and Rabat, Sale | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 422 | 0 | NR | NR | |

| Khattabi, 2005 [131] | 2004 | National | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | NR | 0.4 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 2013 [132] | 2006 | National | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 1180 | 0.2 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 2013 [132] | 2007 | National | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 986 | 0.4 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 2013 [132] | 2008 | National | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 1237 | 0.5 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 2013 [132] | 2009 | National | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 1103 | 0.3 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 2013 [132] | 2010 | National | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 1181 | 0.7 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 2013 [133] | 2011 | Fes, Meknes, and Laayoune Boujdour | VCT | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 88 | 2.3 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 2013 [132] | 2012 | National | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 1070 | 0.3 | NR | NR | |

| MOH, 2013 [133] | 2012 | National | VCT and STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 1297 | 0.4 | NR | NR | |

| Pakistan | Mujeeb, 1993 [134] | NR | Karachi | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 32 | 0 | NR | NR |

| Memon, 1997 [135] | 1994–1995 | Hyderabad | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees (predom. men) | 50 | 0 | NR | NR | |

| NAP, 1996 [136] | 1995 | Karachi | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees (predom. men) | 402 | 0 | NR | NR | |

| NAP, 1996 [136] | 1995 | Lahore | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees (predom. men) | 295 | 0 | NR | NR | |

| Rehan, 2003 [137] | 1999 | Karachi | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 138 | 0 | NR | 43% reported contact with FSWs, 12% with casual heterosexual contact, 11.6% with MSM, 18.4% reported bisexuality | |

| Rehan, 2003 [137] | 1999 | Lahore | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 148 | 0 | NR | NR | |

| Rehan, 2003 [137] | 1999 | Peshawar | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 93 | 1.1 | NR | NR | |

| Rehan, 2003 [137] | 1999 | Quetta | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 86 | 0 | NR | NR | |

| Bhutto, 2011 [138] | 2000–2009 | Larkana | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 4288 | 0.06 | NR | 83% reported a history of contact with FSWs | |

| Bokhari, 2007 [68] | 2004 | Karachi | Trucking agencies | SRS | Truck driver clients of FSWs | 120 | 0 | NR | Subsample including only clients of FSWs | |

| Razvi, 2014 [139] | 2010–2014 | Abbottabad | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 465 | 1.1 | NR | 8% refused to answer, 70% of the rest reported contact with FSWs, 21% with MSM, 7.5% with married women | |

| NAP, 2012 [140] | 2011 | Balochistan | Mines | SRS | Mine workers clients of FSWs | 381 | 0 | NR | Subsample including only men reporting contact with FSWs at last sex | |

| Somalia | Ismail, 1990 [141] | 1986 | Mogadishu | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 101 | 0 | NR | 54% reported contact with FSWs |

| Scott, 1991 [106] | 1989 | Mogadishu | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 50 | 0 | NR | NR | |

| Burans, 1990 [105] | NR | Mogadishu | NR | Conv | STI clinic attendees (80% soldiers) | 45 | 0 | NR | 40% reported contact with FSWs | |

| Corwin, 1991 [107] | 1990 | Chismayu, Merca, and Mogadishu | NR | Conv | Partners of FSWs | 26 | 0 | NR | Partners of FSWs | |

| Duffy, 1999 [142] | 1999 | Hargeisa | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 106 | 0.9 | NR | NR | |

| WHO, 2005 [143] | 2004 | Bossasso | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 78 | 1.3 | NR | NR | |

| WHO, 2005 [143] | 2004 | Hargeisa | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 52 | 9.6 | NR | NR | |

| WHO, 2005 [143] | 2004 | Mogadishu | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 46 | 4.4 | NR | NR | |

| UNHCR, 2007 [144] | 2006–2007 | Dadaab refugee camp | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 199 | 0.5 | NR | NR | |

| Ismail, 2007 [145] | 2007 | Hargeisa | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 108 | 7.4 | NR | NR | |

| NAP, 2010 [146] | 2007 | Puntland | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | NR | 1.5 | NR | NR | |

| Sudan | McCarthy, 1989 [147] | 1987 | Port Sudan and Suakin | NR | Conv | Clients of FSWs | 157 | 0 | NR | Subsample including only clients of FSWs |

| McCarthy, 1989 [148] | 1987–1988 | Gederef, Port Sudan, Kassala, Omdurman, and Juba | Outpatient military clinics | Conv | Soldiers clients of FSWs | 398 | 2.5 | NR | Subsample including only soldiers reporting a history of contact with FSWs | |

| McCarthy, 1995 [109] | NR | Juba, South Sudan | STI clinics | Conv | STI clinic attendees clients of FSWs | 37 | 13.5 | NR | Subsample including only men reporting contact with FSWs in the past 10 years | |

| US Cens. Bureau, 2017 [149] | 2004 | Khartoum | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 72 | 1.4 | NR | NR | |

| US Cens. Bureau, 2017 [149] | 2004 | Red Sea | Sent. surv. | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 164 | 1.8 | NR | NR | |

| Yemen | Abdol-Quauder, 1993 [150] | 1992 | Sanaa | STI clinic | Conv | STI clinic attendees | 30 | 0 | NR | NR |

The table is sorted by year(s) of data collection or year of publication if the year of data collection was not reported

Abbreviations: Cens Census, CI confidence interval, Conv convenience, FSWs female sex workers, MENA HIV ESP MENA HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Synthesis Project, MOH Ministry of Health, NAP National AIDS Program, NR not reported, OMS Organisation Mondiale de la Sante, Predom. predominantly, Prev prevalence, Sent. surv. sentinel surveillance, SRS simple random sampling, STI sexually transmitted infection, SyRS systematic random sampling, UNHCR United Nations Higher Commission for Refugees, VCT voluntary counseling and testing, WHO World Health Organization

*The decimal places of the prevalence figures are as reported in the original reports, but prevalence figures with more than one decimal places were rounded to one decimal place, with the exception of those below 0.1%. Most studies did not report the 95% CIs associated with prevalence

Quality assessment

Additional file 1: Tables S6-S9 show the summarized and study-specific quality assessments for the size estimation and HIV prevalence studies in FSWs and clients. Almost all size estimation studies used clear/valid sex work definitions, and > 70% used rigorous size estimation methodologies. Similarly, > 70% of prevalence studies in FSWs used clear/valid sex work definitions and probability-based sampling for participants’ recruitment. Meanwhile, > 85% of prevalence studies in clients used convenience sampling.

Overall, studies were of reasonable quality. The majority of size estimation studies in FSWs and clients had low ROB on ≥ 2 quality domains (94.4% and 82.1%, respectively), and none had high ROB on ≥ 2 domains. Similarly, 85.0% of prevalence studies in FSWs and 39.4% of studies in clients had low ROB on ≥ 2 domains (studies among STI clinic attendees mostly used convenience sampling, and few reported on contact with FSWs), while 0.7% and 6.1% had high ROB on ≥ 2 domains, respectively.

Pooled mean HIV prevalence

The pooled mean HIV prevalence for the MENA region was 1.4% (95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.1–1.8%) in FSWs and 0.4% (95% CI = 0.1–0.7%) in clients (Table 5). A difference was observed between the median prevalence and the pooled mean prevalence due to the high clustering of prevalence measures close to zero.

In FSWs, the national-level pooled mean prevalence was 0 or < 1% in most countries (low-level epidemics); between 1 and 5% (intermediate-intensity epidemics) in Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Somalia, and Sudan; and > 5% (concentrated epidemics) in Djibouti (17.9%, 95% CI = 13.6–22.6%) and South Sudan (17.3%, 95% CI = 8.7–28.1%).

In clients/male STI clinic attendees, the national-level pooled mean prevalence was mostly 0 or < 1%. However, high prevalence was estimated in Djibouti (5.4%, 95% CI = 1.5–10.8%) and South Sudan (13.5%, 95% CI = 4.5–28.8%).

There was evidence for the heterogeneity in effect size (prevalence) in meta-analyses. p value for Cochran’s Q statistic was mostly < 0.0001, prediction intervals were wide, and I2 was often > 50% indicating that most between-study variability is due to the true differences in prevalence across studies rather than chance.

Associations with prevalence, sources of between-study heterogeneity, and temporal trend

Univariable meta-regressions for FSWs demonstrated strong evidence for an association with odds for subregion, population type, sample size, year of data collection, and response rate (Table 6). Meanwhile, there was poor evidence for an association with sampling methodology, validity of sex work definition, and HIV ascertainment, which were hence dismissed from inclusion in the multivariable model. Most variability in odds was explained by subregion (adjusted R2 = 39.8%).

Table 6.

Results of meta-regression analyses to identify associations with HIV prevalence, sources of between-study heterogeneity, and trend in HIV prevalence in FSWs in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

| Variables | Studies | Samples | Univariable analyses | Multivariable analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | Total N | OR (95% CI) | LR test p value€ | Variance explained R2£ (%) | AOR (95% CI) | p value | LR test p value¥ | ||

| Country/subregion* | |||||||||

| Eastern MENA | Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan | 122 | 47,533 | 1.00 | < 0.001 | 39.80 | 1.00 | < 0.001 | |

| Fertile Crescent | Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria | 136 | 132,758 | 0.17 (0.10–0.27) | 0.21 (0.12–0.36) | < 0.001 | |||

| Bahrain and Yemen | Bahrain and Yemen | 11 | 2491 | 2.60 (0.78–8.67) | 1.77 (0.52–6.01) | 0.357 | |||

| Horn of Africa | Djibouti, Somalia, South Sudan | 93 | 29,509 | 33.45 (19.77–56.58) | 45.43 (24.66–83.68) | < 0.001 | |||

| North Africa | Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia | 312 | 75,428 | 3.14 (2.09–4.72) | 2.90 (1.80–4.68) | < 0.001 | |||

| Population type | Street-based, venue-based, and other FSWs† | 619 | 220,363 | 1.00 | 0.002 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 0.163 | |

| Bar girls | 55 | 67,356 | 0.33 (0.17–0.67) | 0.66 (0.37–1.18) | 0.163 | ||||

| Total sample size of tested FSWs | < 100 participants | 75 | 4008 | 1.00 | 0.001 | 1.54 | 1.00 | < 0.001 | |

| ≥ 100 participants | 599 | 283,711 | 0.36 (0.20–0.65) | 0.35 (0.21–0.56) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Median year of data collection** | < 1993 | 104 | 36,038 | 1.00 | 0.001 | 1.96 | 1.00 | 0.005 | |

| 1993–2002 | 169 | 98,221 | 0.31 (0.17–0.56) | 1.18 (0.71–1.95) | 0.522 | ||||

| ≥ 2003 | 401 | 153,460 | 0.57 (0.33–0.97) | 2.03 (1.24–3.33) | 0.005 | ||||

| Sampling methodology | Non-probability sampling | 570 | 254,072 | 1.00 | 0.217 | 0.08 | – | – | – |

| Probability-based sampling | 104 | 33,647 | 0.72 (0.42–1.21) | – | – | – | |||

| Response rate | ≥ 60% | 96 | 31,161 | 1.00 | 0.043 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.544 | |

| < 60%/unclear | 62 | 14,102 | 2.76 (1.24–6.13) | 1.17 (0.60–2.27) | 0.645 | ||||

| Not applicable‡ | 516 | 242,456 | 1.37 (0.80–2.37) | 1.33 (0.79–2.23) | 0.279 | ||||

| Validity of sex work definition | Clear and valid definition | 117 | 36,431 | 1.00 | 0.161 | 0.25 | – | – | – |

| Poorly defined/unclear | 41 | 8832 | 2.35 (0.96–5.73) | – | – | – | |||

| Not applicable‡ | 516 | 242,456 | 1.15 (0.70–1.90) | – | – | – | |||

| HIV ascertainment | Biological assays | 157 | 44,894 | 1.00 | 0.786 | 0 | – | – | – |

| Self-report, unclear, and not applicable‡ | 517 | 242,825 | 0.94 (0.60–1.47) | – | – | – | |||

Abbreviations: AOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval, FSWs female sex workers, LR likelihood ratio, OR odds ratio

*Countries were grouped based on geography and similarity in HIV prevalence levels. Given the large fraction of studies with zero HIV prevalence, particularly in the Fertile Crescent, an increment of 0.1 was added to a number of events in all studies when generating log odds, and Eastern MENA was thus used also as a statistically better reference. While this choice of increment was arbitrary, other increments yielded the same findings, though some of the effect sizes changed in scale

**Year grouping was driven by independent evidence identifying the emergence of HIV epidemics among both men who have sex with men [10] and people who inject drugs [11] in multiple MENA countries around 2003. Missing values for year of data collection (only six stratified measures) were imputed using data for year of publication adjusted by the median difference between year of publication and median year of data collection (for studies with complete information)

†A large fraction of studies did not separate the different forms of female sex workers, and thus it was not possible to analyze these as separate categories

‡Measures extracted only from routine databases with no reports describing the study methodology were not included in the ROB assessment

€Predictors with p value ≤ 0.1 were considered as showing strong evidence for an association with (prevalence) odds and were hence included in the multivariable analysis

£Adjusted R2 in the final multivariable model = 49.21%

¥Predictors with p value ≤ 0.1 in the multivariable model were considered as showing strong evidence for an association with (prevalence) odds

Multivariable analysis indicated strong subregional differences and explained 49.2% of the variation (Table 6). Compared to Eastern MENA, the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) ranged from 0.2 (95% CI = 0.1–0.4) for the Fertile Crescent to 45.4 (95% CI = 24.7–83.7) for the Horn of Africa. Studies with a larger sample size (≥ 100) showed lower odds (AOR = 0.4, 95% CI = 0.2–0.6).

Compared with studies with data collection pre-1993, studies conducted after 2003 showed strong evidence for higher odds (AOR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.2–3.3). Notably, the trend of increasing odds was evident only after controlling for the strong confounding effect of the subregion. The trend for each subregion was also overall increasing, though the strength of evidence varied across subregions (not shown). Including the year of data collection as a linear term, instead of a categorical variable, using only post-2003 data indicated strong evidence for increasing HIV odds (AOR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.09–1.21, p < 0.0001; not shown). No association was found with the population type or response rate.

Meta-regression analyses for clients demonstrated similar results to those of FSWs, but with wider CIs considering the smaller number of prevalence studies (Additional file 1: Table S10). There was evidence that subregion was associated with HIV odds in clients, but no evidence that sample size or year of data collection explained the between-study heterogeneity.

Sex work context and sexual and injecting risk behaviors

For the detailed sex work context and behavioral measures, we provide here (for brevity) only a high-level summary of key measures.

Sex work context

Across studies, the mean age of FSWs ranged from 19.5 to 37.4, with a median of 27.8 years. Mean age at sexual debut ranged from 14.0 to 22.5 years (median = 17.5), and mean age at sex work initiation ranged from 17.5 to 27.5 years (median = 22.7). Mean duration of sex work ranged from 0.7 to 14.3 years (median = 5.5). A median of 28.0% (range = 0.9–76.6%) of FSWs were single, 30.1% (range = 0–65.5%) were divorced, and 7.0% (range = 0–27.2%) were widowed.

Reported condom use

There was high heterogeneity in reported condom use among FSWs by sexual partnership type and across and within countries (Additional file 1: Table S11). Condom use at last sex with clients ranged from 1.2 to 94.8% (median = 44.0%). Consistent condom use with clients ranged from 0 to 95.2% (median = 26.3%) among all FSWs and from 38.2 to 45.3% (median = 42.3%) among FSWs reporting condom use with clients.

Median condom use at last sex with regular clients was 55.9% (range = 25.5–92.0%) and that with one-time clients was 58.3% (range = 28.5–96.0%). Less condom use at last sex was found with non-paying partners (median = 22.0%, range = 4.9–78.3%). There was also variability in condom use at last anal sex (range = 0–86.5%), though low levels were generally reported (median = 18.5%).

The median fraction of FSWs who reported having a condom at the time of study interview was 12.5% (range = 0–66.1%).

Clients and partners

Studies varied immensely in types of measures reporting data on clients and partners. Some reported a mean number of regular/non-regular clients, but over various time frames. Others reported different distributions for the number of clients (and by client type), also over various time frames. Summarizing the evidence was therefore challenging, given the large type of measure variability.

This being said, the mean number of clients in the past month ranged from 4.4 to 114.0, with a median of 34.0 clients. Median fraction of FSWs reporting (during the past month) < 5 clients, 5–9 clients, and 10+ clients was 28.5%, 28.1%, and 19.1%, respectively. FSWs were equally likely to report regular and one-time clients during the past month (medians = 80.0% and 81.0%, ranges = 54.3–92.4% and 59.2–97.5%, respectively).

FSWs reported a distribution of sex acts in the past week, with a median of 41.2% reporting 1–2 acts, 32.0% reporting 3–4 acts, and 12.9% reporting 5+ acts. Anal sex with clients in the past month was reported by a median of 8.0% (range = 2.3–100%).

Median fraction of FSWs that are married/cohabiting was 45.3% (range = 0–99.6%), while that of FSWs reporting non-paying partners was 48.5% (range = 6.8–86.2%). The mean number of non-paying partners in the past month ranged between 1 and 3, with about two thirds reporting only one partner.

Only few studies investigated group sex: 7.7% [90] of FSWs reported ever engaging in group sex, 6.2% [68] and 12.9% [68] reported group sex in the past month, and 10.0% [58] in the past week.

Injecting risk behavior, sex with PWID, and substance use

There was a large variability in injecting risk behavior and substance use among FSWs, but the highest levels of injecting drug use were reported in Iran and Pakistan (Additional file 1: Table S12). Median of current/recent injecting drug use was 2.1% (range = 0–26.6%), but the majority of studies were from Pakistan. Studies in Iran reported a history of injecting drug use in the range of 6.1–18.0% (median of 13.6%) among all FSWs and range of 16.4–25.5% (median of 22.3%) among only ever/active drug users. A history of injecting drug use was reported by < 1% (median) of all FSWs (range = 0%–11.8%) in the rest of MENA countries.

Fraction of FSWs reporting current/recent sex with PWID ranged from 0.5 to 13.6% within Afghanistan and 0–54.9% within Pakistan, with medians of 5.2% and 5.6%, respectively. Sex with PWID was reported at 23.6% [93] among FSWs in Iran.

Close to a third of FSWs reported ever using drugs (median = 27.0%, range = 1.7–90.7%). A median of 8.9% reported current/recent drug use (range = 0.6–59.0%). Any substance use before/during sex was reported by 37.8% (median, range = 1.0–88.1%). Alcohol use before/during sex was reported by 44.1% (median, range = 3.0–70.7%).

Knowledge of HIV/AIDS and perception of risk

Knowledge of HIV/AIDS was generally high among FSWs across MENA (Additional file 1: Table S13). Vast majority of FSWs ever heard of HIV (median = 81.9%, range = 25.4–100%) and were aware of sexual (median = 72.0%, range = 50.8–94.9%) and injecting (median = 88.7%, range = 11.5–99.6%) modes of transmission, but to a lesser extent of condoms as a prevention method (median = 51.6%, range = 14.1–89.8%)—condoms were more perceived as a contraception method. Levels of knowledge, however, varied often substantially within the same country.

Overall, FSWs did not perceive themselves at high risk of HIV acquisition (Additional file 1: Table S14). Perception of HIV risk was reported as at-risk (median = 34.6%, range = 22.8–48.5), low-risk (median = 18.3%, range = 7.1–46.9), medium-risk (median = 16.4%, range = 5.3–36.1), and high-risk (median = 14.4%, range = 5.9–32.0).

HIV testing

HIV testing among FSWs varied across countries, but was generally low, with a median fraction of 17.6% (range = 4.0–99.4%) ever tested for HIV (Additional file 1: Table S15). Only a median of 12.1% (range = 0.9–38.0%) of all FSWs tested for HIV in the past 12 months, and nearly two thirds of those who ever tested did so in the past 12 months (median = 59.2%, range = 33.3–82.0%). Majority of FSWs who ever tested were aware of their status (median = 91.9%, range = 60.0–99.0%).

Discussion

Through an extensive, systematic, and comprehensive assessment of HIV epidemiology among FSWs and clients, including data presented in the scientific literature for the first time, we found that HIV epidemics among FSWs have already emerged in MENA, and some appear to have reached their peak. Based on a synthesis and triangulation of evidence from studies on a total of 300,000 FSWs and 30,000 clients, a strong regionalization of epidemics has been identified. In Djibouti and South Sudan, the HIV epidemic is concentrated with a prevalence of ~ 20% in FSWs. In Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Somalia, and Sudan, the epidemic is of intermediate-intensity (prevalence 1–5%). Strikingly, in the remaining countries with available data, the prevalence is < 1%, and most often zero.

A key finding is that HIV prevalence in FSWs has been (overall) growing steadily since 2003. This is the same time in which independent evidence has identified the emergence of major epidemics among both PWID [11] and MSM [10] in MENA. It is probable that the epidemics among these key populations have been bridged to FSWs. An example is Pakistan, where the prevalence among FSWs was < 1% in almost all cities in three consecutive IBBSS rounds between 2005 and 2012 [38, 40, 69]. However, prevalence ranging from 1.5 to 8.8% was documented in half of the cities in the latest round in 2016–2017 [42]. These emerging epidemics among FSWs were preceded by large and growing epidemics first among PWID [11] and then among MSM [10, 11].

Some of the FSW epidemics, particularly those in Djibouti and South Sudan, emerged much earlier, most likely by late 1980s [6], mainly affected by geographic proximity and stronger population links to sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [6]. Djibouti is a port country and the major trade route for Ethiopia and a station for large international military bases [6, 151]. The majority of FSWs operating in Djibouti are Ethiopians catering to the Ethiopian truck drivers transporting shipments from the Djibouti port [84–86]. South Sudan is socio-culturally part of SSA, with a major fraction of FSWs coming from Uganda, Congo, and Kenya [79]. In these MENA countries, HIV in commercial heterosexual sex networks (CHSNs) is well-established and epidemics are concentrated—though at levels lower than the hyper-endemic epidemics observed in SSA [152].

Unlike the epidemics among PWID and MSM [10, 11], the FSW epidemics have been overall growing rather slowly, with the prevalence being mostly < 5%. Strikingly, a considerable fraction of countries still do not appear to have much HIV transmission in CHSNs, with consistently very low prevalence, quite often even at zero level—46.8% of studies in FSWs reported zero prevalence, and 7 out of 18 countries had a pooled mean prevalence of zero or nearly zero. One explanation for the observed low HIV prevalence could be that HIV has not yet been effectively introduced into CHSNs—it took decades for HIV to be effectively introduced into PWID [11] and MSM [10] networks. Another possible factor pertains to the structure of CHSNs, characterized apparently by low connectivity [6, 153, 154], which reduces the risk of HIV being introduced, or efficiently/sustainably transmitted. Unlike PWID and MSM, FSWs are also exposed to HIV mainly through their clients, who have a lower risk of exposure to HIV than themselves, thus possibly contributing to slower epidemic growth [6].

Other factors may also contribute to explaining the observed low HIV prevalence. The synthesized evidence suggests a lower risk environment for FSWs in MENA, compared to other regions. The reported number of clients is rather low at a median of 34 per month, at the lower end of global range [155–158]. Close to half of commercial sex acts are protected through condom use, with no difference between regular and one-time clients, despite noted variability across and within countries. HIV/AIDS knowledge also varies, but is generally substantial, with the majority of FSWs being aware of sexual and injecting modes of transmission, and over half are aware of condoms as a prevention method. Injecting drug use and sex with PWID is low in most countries, except for countries in Eastern MENA, notably Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. Serological markers for hepatitis C virus (a marker of injecting risk) [159–161] are also low in FSWs, assessed at a median of 1.1% (range = 0–9.9%, not shown), with the highest measures reported in Iran [61, 162]. These relatively lower levels of risk behavior than other regions [163–165] stand in contrast to what has been observed in PWID and MSM in MENA [10, 11].

Importantly, with the efficacy of 60% in randomized clinical trials [166–169], male circumcision, which is essentially at universal coverage across MENA [170], may have also slowed, or even substantially reduced HIV transmission in CHSNs leading to the observed low HIV prevalence [171]. Incidentally, the two most affected countries—South Sudan and Djibouti—are nearly the only two major settings where male circumcision is at low coverage in MENA, either nationally, as is the case for South Sudan [170], or among clients of FSWs, as is the case for Ethiopian truckers and international military personnel stationed in Djibouti [151, 170]. Though HIV prevalence will probably continue to increase among FSWs and clients, the high levels of male circumcision coupled with lower levels of risk behavior may prevent significant epidemics, as seen elsewhere [172–174], from materializing in CHSNs in multiple MENA countries.