Abstract

Background

Low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) has a significant impact on postoperative quality of life. Although early closure of an ileostomy is safe in selected patients, functional outcomes have not been investigated. The aim was to compare bowel function and the prevalence of LARS in patients who underwent early or late closure of an ileostomy after rectal resection for cancer.

Methods

Early closure (8–13 days) was compared with late closure (after 12 weeks) of the ileostomy following rectal cancer surgery in a multicentre RCT. Exclusion criteria were: signs of anastomotic leakage, diabetes mellitus, steroid treatment and postoperative complications. Bowel function was evaluated using the LARS score and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Bowel Function Instrument (BFI).

Results

Following index surgery, 112 participants were randomized (55 early closure, 57 late closure). Bowel function was evaluated at a median of 49 months after stoma closure. Eighty‐two of 93 eligible participants responded (12 had died and 7 had a permanent stoma). Rates of bowel dysfunction were higher in the late closure group, but this did not reach statistical significance (major LARS in 29 of 40 participants in late group and 25 of 42 in early group, P = 0·250; median BFI score 63 versus 71 respectively, P = 0·207). Participants in the late closure group had worse scores on the urgency/soiling subscale of the BFI (14 versus 17; P = 0·017). One participant in the early group and six in the late group had a permanent stoma (P = 0·054).

Conclusion

Patients undergoing early stoma closure had fewer problems with soiling and fewer had a permanent stoma, although reduced LARS was not demonstrated in this cohort. Dedicated prospective studies are required to evaluate definitively the association between temporary ileostomy, LARS and timing of closure.

Introduction

Low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision is a common surgical option for patients with potentially curable rectal cancer. Anastomotic leakage is a feared complication after anterior resection as it is associated with a 6–22 per cent increase in postoperative mortality and may result in worse oncological outcomes1, 2. A temporary ileostomy created at the time of the rectal resection may ameliorate the clinical consequences of a potential anastomotic leak3, 4, 5, 6. Typically, patients have a stoma for approximately 5–6 months7, 8, 9, which may have a negative impact on their quality of life10, 11, renal function12, 13, 14, 15 and completion of chemotherapy16. Early closure of an ileostomy, less than 2 weeks after primary resection, has been shown to be safe in selected patients in randomized trials17, 18.

Low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) describes bowel dysfunction after surgical resection of rectal cancer. Identified risk factors for LARS are radiotherapy and low anastomosis19, 20, 21, 22, 23. The underlying mechanisms are likely to be multifactorial, and include neural damage, fibrosis and altered colonic motility24. Use of a diverting stoma has been associated with postrectal resection bowel dysfunction in non‐controlled studies23, 25, 26, 27. Theoretically, this association may be due to alterations in colonic nutrition leading to inflammation, changes in the bacterial flora, and/or atrophy of motility or sensory elements28. Therefore, the duration of a diverting ileostomy may influence the occurrence of LARS.

The aim of this study was to conduct a secondary analysis of the multicentre EASY (Early Closure of Temporary Ileostomy) RCT (NCT01287637), using specifically designed instruments to assess whether patients who undergo early closure of the ileostomy after anterior resection for rectal cancer have a reduced risk of developing LARS compared with those who undergo late closure. A secondary aim was to assess whether the two validated instruments specifically designed to measure postoperative bowel function, the LARS score and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Bowel Function Instrument (BFI), were measuring the same underlying construct.

Methods

The EASY trial was a multicentre RCT conducted in eight Danish and Swedish surgical departments within the Scandinavian Surgical Outcomes Research Group framework (http://www.ssorg.net). The trial protocol29 is available at http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/early/2011/07/29/bmjopen‐2011‐000162.short. Adults who had undergone a low anterior resection with temporary ileostomy formation for the treatment of rectal cancer were eligible. Participants were enrolled after the index surgery (total mesorectal excision and formation of temporary ileostomy) between February 2011 and November 2014. Potential participants were assessed clinically on day 1–4 after index surgery to ensure that there were no signs of postoperative complications, such as infection or anastomotic leakage. The exclusion criteria were: diabetes, ongoing steroid treatment, signs of postoperative complication(s), and inability to understand Danish or Swedish. Before randomization, anastomotic integrity was ensured between days 6 and 8 after the index surgery, by CT with contrast and/or direct visualization using rectoscopy.

Randomization was performed in computer‐generated blocks of six, using opaque, sealed envelopes with a 1 : 1 ratio. Blinding was not possible. Participants randomized to the intervention (early closure) had the ileostomy closed within 8–13 days after index surgery. Participants allocated to the control group (late closure) had the ileostomy closed at a minimum of 12 weeks after the index surgery. The primary endpoint of the study was the rate of complications. Secondary endpoints included health‐related quality of life up to 12 months after rectal resection. These results have been published previously17, 30.

An invitation to participate in further follow‐up regarding functional outcome was sent to all surviving participants between August and October 2017. All participants received the study questionnaire by post. Participants received up to two follow‐up telephone calls. Functional follow‐up comprised completion of two questionnaires, the LARS score and the BFI. The LARS score is derived from responses to five questions, each with associated response categories based on the frequency of symptom occurrence or number of bowel motions (Appendix S1, supporting information)31. Each response is weighted based on the impact on quality of life. A LARS score of 0–20 represents no LARS, 21–29 minor LARS, and 30–42 major LARS. The BFI consists of 18 questions that are divided into subscales as suggested by the authors: dietary, soiling/urgency and frequency (Appendix S2, supporting information)32. The BFI gives an overall score between 0 and 100, with a higher score representing better function. The overall BFI score and the score for each subscale were calculated. Numerical responses to question 1 (frequency of bowel motions per 24 h) were divided into quintiles, with the fifth quintile representing the lowest frequency and given a response of 5 on the ordinal scale, as advised by the authors of the BFI32. For questions 4, 5, 7, 11 and 12, a response of ‘always’ represented the best possible function, so was given the maximum score of 5. For all other questions, a response of ‘always’ represented the worst function, so was given the minimum score of 1. If participants returned questionnaires with multiple responses to a single question, the response that indicated the most severe outcome was used in the analysis. Mean imputation was used to allow calculation of subscale scores that contained missing responses if at least 50 per cent of questions in the subscale were answered. If more than 50 per cent of items in a subscale were missing, the subscale was recorded as missing. There were no missing subscales, but mean imputation was used to calculate 12 subscale scores.

Statistical analysis

An intention‐to‐treat analysis was used. Comparison between treatment groups was undertaken using χ2 test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Tests of significance were two‐sided and the level of significance was 0·05. LARS was analysed as a dichotomized variable (no/minor and major) using a generalized linear model with binomial distribution33. In an adjusted analysis, tumour height and use of radiotherapy were included as co‐variables. Results are presented as a risk ratio with 95 per cent confidence intervals. No corrections for multiplicity were made. The correlation between responses from the BFI and LARS scores was assessed using the Spearman rank order correlation coefficient. SPSS® Statistics for Macintosh® version 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) and GraphPad Prism® version 7 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA) were used for statistical analysis.

Results

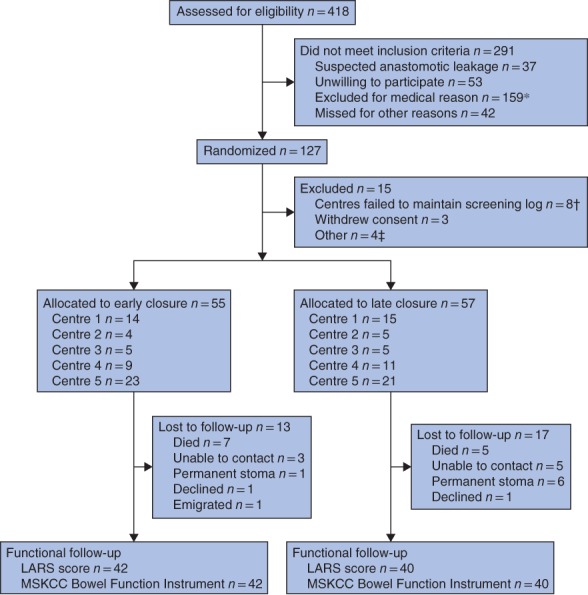

The EASY trial enrolled 112 participants. There were 100 participants alive at the time of functional follow‐up. Median follow‐up was 50 (range 34–77) months after index surgery and 49 (range 24–74) months after stoma closure. One of 42 participants in the early closure group had a permanent stoma, compared with six of 40 in the late closure group (P = 0·054); two of the latter patients had the stoma because of persisting severe bowel dysfunction (Table 1). Of the remaining 93 patients, 82 (88 per cent) responded to the functional questionnaires (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Reasons for formation of a permanent stoma in patients lost to follow‐up

| Reason for permanent stoma | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| Early closure group | 1 |

| Anastomotic leak and associated necrotizing fasciitis>12 months after stoma closure | 1 |

| Late closure group | 6 |

| Bowel dysfunction – patient preference for stoma>12 months after stoma closure | 2 |

| Stenosis <12 months after stoma closure | 1 |

| Anastomotic stricture dilated and perforated withresulting sepsis and cardiopulmonary arrest(grade IVa*) | 1 |

| Anastomotic leak 9 months after stoma closure | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 |

According to Clavien–Dindo classification34.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram for EASY trial17 *Paralytic ileus (24 patients), Hartmann's procedure with intersphincteric dissection (16), delayed postoperative recovery (15), perioperative complications (7), other infection (5), reoperation (7), high stoma output (5), pulmonary embolism (1), ulcerative colitis (1), extensive cancer disease (3), cardiovascular disease (2), language difficulties (5), diabetes (28), permanent or no stoma (29), steroid treatment (3), other (8). †Centre 6 (2 patients), centre 7 (3) and centre 8 (3). ‡Allocated to early closure, but not possible to carry out operation within 8–13 days (1 patient), early stoma closure outside study (2), patient randomized, but no further information available (1). LARS, low anterior resection syndrome; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Participant and treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 2. There were more women in the early closure group (22 of 42 versus 12 of 40; P = 0·047), but there were no other differences in participant or treatment characteristics between the groups. Median follow‐up after restoration of bowel continuity in the early and late closure groups was 52 and 44 months respectively. There were no differences in any characteristics between participants who responded to the questionnaires and those who did not complete functional follow‐up.

Table 2.

Participant and treatment characteristics

| Early closure (n = 42) | Late closure (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) * | ||

| At index surgery | 67 (53–71) | 68 (63–73) |

| At follow‐up (years)* | 71 (58–76) | 72 (67–77) |

| Sex ratio (F : M) | 22 : 20 | 12 : 28¶ |

| BMI (kg/m2) * | 24 (23–27) | 24 (22–26) |

| Co‐morbidity † | ||

| Ischaemic heart disease | 5 | 6 |

| Hypertension | 14 | 7 |

| COPD | 2 | 1 |

| Renal disease | 0 | 0 |

| Other‡ | 5 | 1 |

| Smoker | 4 | 2 |

| Clinical stage (UICC) § | ||

| I | 11 | 12 |

| II | 18 | 10 |

| III | 11 | 13 |

| IV | 1 | 1 |

| Tumour height (cm from anal verge) | ||

| 5–9 | 23 | 16 |

| 10–15 | 18 | 24 |

| ≥ 15 | 1 | 0 |

| Radiotherapy | 11 | 10 |

| Short course | 9 | 7 |

| Long course | 2 | 3 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 13 | 18 |

| Duration of ileostomy (days) * | 11 (10–14) | 150 (100–251) |

| Duration of follow‐up (months) * | ||

| From index surgery | 52 (44–59) | 49 (43–58) |

| From stoma closure | 52 (44–59) | 44 (35–53) |

Values are median (i.q.r.).

Data missing for two patients in the late closure group.

In early closure group: asthma (1), Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia/non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (1), osteoporosis (1), Sjögren's syndrome (1), thyrotoxicosis (1); in late closure group: hypercholesterolaemia (1).

Three patients with late closure had clinical stage T0 N0 M0 disease; data on clinical stage missing for one patient in each group. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

P = 0·047 (2‐sided Fisher's exact test).

Low anterior resection syndrome score

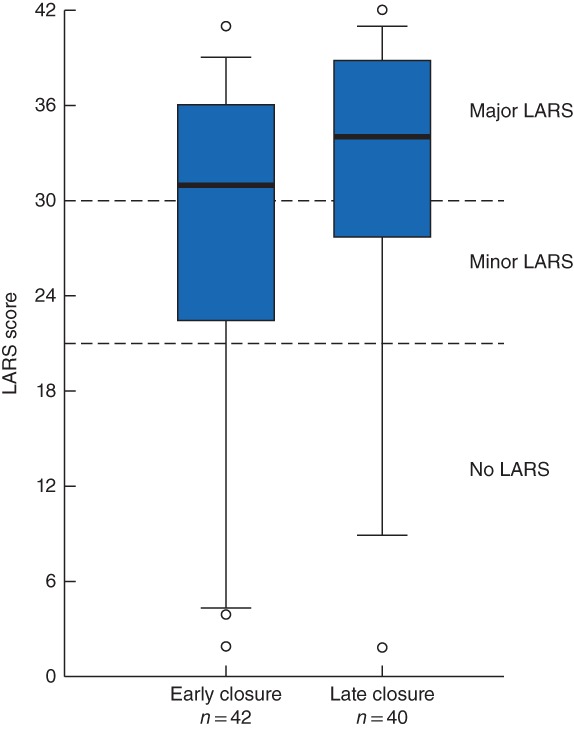

Overall, 54 patients reported major LARS (66 per cent; 25 in early group and 29 in late group), 12 reported minor LARS (15 per cent; 7 and 5 participants respectively) and 16 reported no LARS (20 per cent; 10 and 6 participants respectively). The median LARS scores for the early and late closure groups were 31 (i.q.r. 22–36) and 34 (28–39) respectively (Fig. 2). The prevalence of LARS (major or minor) was 32 of 42 and 34 of 40 in the early and late closure groups respectively (risk ratio 0·89, 95 per cent c.i. 0·72 to 1·11; P = 0·291). The results were similar after adjusting for tumour height and use of radiotherapy (risk ratio 0·89, 0·72 to 1·11; P = 0·314).

Figure 2.

Distribution of lower anterior resection syndrome scores for participants with early and late ileostomy closure Median scores (bold line), interquartile range (box) and 5–95th percentile (error bars) are shown. Symbols represent outliers. Boundaries between the lower anterior resection syndrome (LARS) categories are denoted by dashed lines.

Higher rates of incontinence to faeces (21 of 42 versus 28 of 40; P = 0·076) and flatus (36 of 42 versus 36 of 40; P = 0·738), increased stool frequency (14 of 42 versus 15 of 40; P = 0·818), clustering (36 of 42 versus 37 of 40; P = 0·483) and urgency (33 of 42 versus 33 of 40; P = 0·783) were found in the late closure group, but were not statistically significant.

Memorial Sloan Ketting Cancer Center Bowel Function Instrument

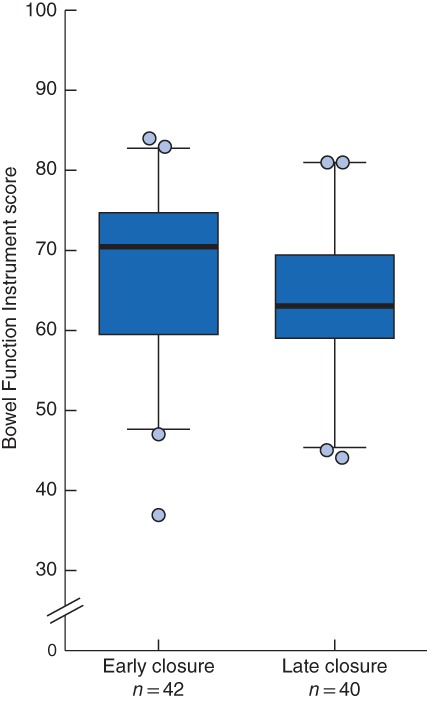

There were no significant differences between early and late closure with regard to median overall BFI scores (71 (i.q.r. 59–75) and 63 (60–70) respectively; P = 0·207) or the frequency (22 (21–25) versus 22 (20–24); P = 0·437) and dietary (16 (13–18) versus 16 (12–18); P = 0·939) subscales (Fig. 3). However, patients undergoing late closure had worse scores on the urgency/soiling subscale than those in the early closure group (14 (6–18) versus 17 (9–20); P = 0·017).

Figure 3.

Distribution of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Bowel Function Instrument scores for participants with early and late ileostomy closure Median scores (bold line), interquartile range (box) and 5–95th percentile (error bars) are shown. Symbols represent outliers. Higher scores represent better function.

A strong negative correlation was noted between the two scoring systems specifically designed to measure LARS (ρ = – 0·72, P < 0·001). The coefficient of variation was 70 per cent for the LARS score compared with 16 per cent for the BFI.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that a substantial proportion of participants have severe bowel dysfunction many months after ileostomy reversal. Participants in the late closure group had worse scores on the soiling/urgency subscale of the BFI. Despite higher rates of bowel dysfunction, including more permanent stomas in the late closure group, there was no statistically significant difference in LARS between the groups.

This is the first assessment of whether patients who undergo early closure of ileostomy after anterior resection for rectal cancer have less risk of developing LARS. A single retrospective analysis23 investigated the association between timing of ileostomy closure and LARS, and found no association. However, all participants in that study had an ileostomy for at least 3 months.

The overall prevalence of major LARS in this study (66 per cent) is higher than might be expected from the literature. Only one‐quarter of participants received radiotherapy, all tumours were above 5 cm and half were more than 10 cm above the anal verge. It is possible that this study offers a more accurate representation of the population prevalence as there was a high response rate (88 per cent) and so minimal selection bias. The high prevalence of LARS in this study may reflect the evaluation of a population at inherently greater risk of developing LARS, that is patients requiring an ileostomy. Several non‐controlled studies20, 23, 26 have shown an association between use of a temporary ileostomy and LARS. However, this association could be the result of confounding factors as patients with a distal tumour who undergo radiotherapy are at greater risk of developing LARS, but are also at higher risk of anastomotic leakage and more likely to have an ileostomy23, 26. In the present study, similar results were obtained in unadjusted analysis and after adjusting for tumour height and use of radiotherapy.

The BFI scores for the late closure group are consistent with those in previous studies32, 35, 36. An interesting finding of the present study is that patients who had late ileostomy closure experienced greater problems with soiling, according to the BFI subscale. This subscale included questions regarding pad use, soiling and need to alter activities owing to bowel function. The LARS score does not mention soiling but asks about accidental leakage of liquid stool. Accidental leakage was more common in the late closure group, although the difference between groups did not reach statistical significance. Urgency is one of the most debilitating components of postoperative bowel dysfunction according to patients, but is frequently underestimated by clinicians31, 37. The urgency/soiling subscale is a misnomer as it does not include any questions about urgency, but question 11 in the MSKCC BFI asks about the ability to defer defecation. The median response in the early closure group was ‘most of the time’, whereas it was ‘sometimes’ possible for participants in the late closure group to be able to wait for 15 min to get to the toilet when they felt that they were going to have a bowel motion. Both the LARS score and the BFI questions regarding urgency showed that a greater proportion of people experience urgency after late closure, but neither difference between the treatment groups achieved statistical significance.

The secondary aim of this study was to provide a direct comparison of patient reporting using the LARS score and MSKCC BFI. These results showed a strong correlation between the two patient‐reported outcome scales, confirming that they are measuring the same underlying construct. The brevity of the LARS score and the greater dispersion of LARS scores suggest that the latter tool may be more appropriate than the BFI for a brief clinical assessment to identify patients who require further follow‐up for postoperative bowel dysfunction. The comprehensive BFI may be more suitable for longitudinal assessment of functional outcome as it has greater sensitivity to detect differences in symptomatology, as shown by the results on the urgency/soiling subscale here.

The strengths of this study are its randomized design and the high response rate. The major weakness is that it is a secondary analysis. The sample size for the EASY trial was calculated to achieve 80 per cent power to detect a reduction in mean annual complications17, and not a difference in functional outcome. In addition, the exclusion of participants who may have the most severe bowel dysfunction (those who opted for a permanent stoma) has probably led to an underestimation of major LARS in the late closure group. The higher proportion of women in the early closure group may have also led to an underestimation of the difference in rates of LARS between the treatment groups, as women have higher rates of LARS both after rectal resection and within the Danish population in other studies20, 38. Another limitation is the cross‐sectional assessment of LARS. A longitudinal assessment would have been preferable. However, the minimum follow‐up for all participants was 24 months after restoration of bowel continuity and by this stage functional outcomes would be expected to be relatively stable.

LARS represents a significant burden for both rectal cancer survivors and the healthcare system. This study found that the prevalence of major LARS was up to 73 per cent for patients who had an ileosomy, if closed at the conventional time. The results indicate that specifically powered prospective randomized studies are required to assess definitively whether early closure of an ileostomy mitigates the development of LARS. It is anticipated that the present results will be informative in appropriate trial design.

Snapshot quiz 19/8

Supporting information

Appendix S1. LARS Score (31)

Appendix S2. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Bowel Function Instrument, adapted from (32)

Acknowledgements

C.K and J.P. contributed equally to this work. C.K. is funded by the Auckland Medical Research Foundation Ruth Spencer Fellowship. J.P. has received funding from the Agreement Concerning Research and Education of Doctors (ALFGBG‐682731). E.A. has received funding from the Swedish Research Council (2012‐1786), the Swedish Cancer Society (2013/500), Sahlgrenska University Hospital, the Agreement Concerning Research and Education of Doctors (ALFGBG‐366481, ALFGBG‐526501 and ALFGBG‐493341), the Swedish Society of Medicine (SLS‐247661 and SLS‐412151) and the Lions Väst Cancer Foundation.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Presented to the European Society of Coloproctology 13th Scientific and Annual Meeting, Nice, France, September 2018

References

- 1. Rullier E, Laurent C, Garrelon JL, Michel P, Saric J, Parneix M. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection of rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lu ZR, Rajendran N, Lynch AC, Heriot AG, Warrier SK. Anastomotic leaks after restorative resections for rectal cancer compromise cancer outcomes and survival. Dis Colon Rectum 2016; 59: 236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Montedori A, Cirocchi R, Farinella E, Sciannameo F, Abraha I. Covering ileo‐ or colostomy in anterior resection for rectal carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; (5)CD006878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hüser N, Michalski CW, Erkan M, Schuster T, Rosenberg R, Kleeff J et al Systematic review and meta‐analysis of the role of defunctioning stoma in low rectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg 2008; 248: 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu SW, Ma CC, Yang Y. Role of protective stoma in low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a meta‐analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 18 031–18 037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matthiessen P, Hallböök O, Rutegård J, Simert G, Sjödahl R. Defunctioning stoma reduces symptomatic anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection of the rectum for cancer: a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg 2007; 246: 207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gessler B, Haglind E, Angenete E. Loop ileostomies in colorectal cancer patients – morbidity and risk factors for nonreversal. J Surg Res 2012; 178: 708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams LA, Sagar PM, Finan PJ, Burke D. The outcome of loop ileostomy closure: a prospective study. Colorectal Dis 2008; 10: 460–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. David GG, Slavin JP, Willmott S, Corless DJ, Khan AU, Selvasekar CR. Loop ileostomy following anterior resection: is it really temporary? Colorectal Dis 2010; 12: 428–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsunoda A, Nakao K, Hiratsuka K, Tsunoda Y, Kusano M. Prospective analysis of quality of life in the first year after colorectal cancer surgery. Acta Oncol 2007; 46: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O'Leary DP, Fide CJ, Foy C, Lucarotti ME. Quality of life after low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision and temporary loop ileostomy for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg 2001; 88: 1216–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Messaris E, Sehgal R, Deiling S, Koltun WA, Stewart D, McKenna K et al Dehydration is the most common indication for readmission after diverting ileostomy creation. Dis Colon Rectum 2012; 55: 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beck‐Kaltenbach N, Voigt K, Rumstadt B. Renal impairment caused by temporary loop ileostomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 2011; 26: 623–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Woods R, Fielding A, Moosvi SR, Wharton R, Shaikh I, Hernon J et al Ileostomy is associated with chronically impaired renal function after rectal cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis 2017; 19(Suppl 2): 32. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gessler B, Haglind E, Angenete E. A temporary loop ileostomy affects renal function. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014; 29: 1131–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Robertson JP, Wells CI, Vather R, Bissett IP. Effect of diversion ileostomy on the occurrence and consequences of chemotherapy‐induced diarrhea. Dis Colon Rectum 2016; 59: 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Danielsen AK, Park J, Jansen JE, Bock D, Skullman S, Wedin A et al Early closure of a temporary ileostomy in patients with rectal cancer: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2017; 265: 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alves A, Panis Y, Lelong B, Dousset B, Benoist S, Vicaut E. Randomized clinical trial of early versus delayed temporary stoma closure after proctectomy. Br J Surg 2008; 95: 693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen TY, Wiltink LM, Nout RA, Meershoek‐Klein Kranenbarg E, Laurberg S, Marijnen CA et al Bowel function 14 years after preoperative short‐course radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomized trial. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2015; 14: 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Battersby NJ, Bouliotis G, Emmertsen KJ, Juul T, Glynne‐Jones R, Branagan G et al; UK and Danish LARS Study Groups. Development and external validation of a nomogram and online tool to predict bowel dysfunction following restorative rectal cancer resection: the POLARS score. Gut 2018; 67: 688–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hughes DL, Cornish J, Morris C; LARRIS Trial Management Group. Functional outcome following rectal surgery – predisposing factors for low anterior resection syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017; 32: 691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kupsch J, Jackisch T, Matzel KE, Zimmer J, Schreiber A, Sims A et al Outcome of bowel function following anterior resection for rectal cancer – an analysis using the low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) score. Int J Colorectal Dis 2018; 33: 787–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jimenez‐Gomez LM, Espin‐Basany E, Trenti L, Martí‐Gallostra M, Sánchez‐García JL, Vallribera‐Valls F et al Factors associated with low anterior resection syndrome after surgical treatment of rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2018; 20: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bryant CL, Lunniss PJ, Knowles CH, Thaha MA, Chan CL. Anterior resection syndrome. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: e403–e408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walma MS, Kornmann VN, Boerma D, de Roos MA, van Westreenen HL. Predictors of fecal incontinence and related quality of life after a total mesorectal excision with primary anastomosis for patients with rectal cancer. Ann Coloproctol 2015; 31: 23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu F, Guo P, Shen Z, Gao Z, Wang S, Ye Y. [Risk factor analysis of low anterior resection syndrome after anal sphincter preserving surgery for rectal carcinoma.] Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi 2017; 20: 289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wells CI, Vather R, Chu MJ, Robertson JP, Bissett IP. Anterior resection syndrome – a risk factor analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 19: 350–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baek SJ, Kim SH, Lee CK, Roh KH, Keum B, Kim CH et al Relationship between the severity of diversion colitis and the composition of colonic bacteria: a prospective study. Gut Liver 2014; 8: 170–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Danielsen AK, Correa‐Marinez A, Angenete E, Skullmann S, Haglind E, Rosenberg J; SSORG (Scandinavian Outcomes Research Group). Early closure of temporary ileostomy – the EASY trial: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2011; 1: e000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Park J, Danielsen AK, Angenete E, Bock D, Marinez AC, Haglind E et al Quality of life in a randomized trial of early closure of temporary ileostomy after rectal resection for cancer (EASY trial). Br J Surg 2018; 105: 244–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Low anterior resection syndrome score: development and validation of a symptom‐based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2012; 255: 922–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Temple LK, Bacik J, Savatta SG, Gottesman L, Paty PB, Weiser MR et al The development of a validated instrument to evaluate bowel function after sphincter‐preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 1353–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weisberg S. Applied Linear Regression (3rd edn). John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ihn MH, Kang SB, Kim DW, Oh HK, Lee SY, Hong SM. Risk factors for bowel dysfunction after sphincter‐preserving rectal cancer surgery: a prospective study using the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center bowel function instrument. Dis Colon Rectum 2014; 57: 958–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hou XT, Pang D, Lu Q, Yang P, Jin SL. Bowel dysfunction and self‐management for bowel symptoms after sphincter‐preserving surgery: a cross‐sectional survey of Chinese rectal cancer patients. Cancer Nurs 2017; 40: E9–E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen TY, Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Bowel dysfunction after rectal cancer treatment: a study comparing the specialist's versus patient's perspective. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e003374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Juul T, Elfeki H, Christensen P, Laurberg S, Emmertsen KJ, Bager P. Normative data for the low anterior resection syndrome score (LARS Score). Ann Surg 2018; 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. LARS Score (31)

Appendix S2. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Bowel Function Instrument, adapted from (32)